France

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Monsieur Bayrou

Monsieur le président has appointed François Bayrou as Prime Minister of France – for how long, who knows.

It is worth revisiting the assessment of him the late Maurice Druon (1918-2009) published in the pages of Le Figaro in 2004:

Monsieur François Bayrou, a secondary character and destined to remain so, is remarkable only for his perseverance in undermining the higher interests of France. He eminently possesses what the English call ‘nuisance value’.

At what point did his self-image begin to cloud his judgement? Here is a Béarnais, the son of a farmer, who, gifted for studies, became an agrégé in classical literature. At twenty-eight, he took his first steps in politics by entering the office of Monsieur Méhaignerie, Minister of Agriculture. At the same time, he joined the centrist party that Giscard d’Estaing created to serve his personal elevation. This party, which participated in overthrowing General de Gaulle in 1969, would become the UDF.

Monsieur Bayrou settled there and prospered. He was elected general councillor in his native department, then regional councillor. He was also an advisor to Monsieur Pierre Pfimlin, to the presidency of the European Assembly. Monsieur Pfimlin was an excellent man in every respect, who exercised very high functions with rectitude. He had only one fault: he was a centrist, that is to say, like all centrists, he was mistaken about the hierarchy of values.

He is credited with having made Paris lose its status as the capital of Europe. Indeed, it was agreed between Adenauer and de Gaulle that the institutions of the European Community would have their headquarters nearby. A large complex would be built in the near Paris region. On this, Pfimlin, an Alsatian, intervened, proclaiming: “Strasbourg, Strasbourg… the link between France and Germany, between the two cultures… reconciliation… Strasbourg, a symbolic city!” Could Alsace be insulted? The Parisian project was shelved.

The move was well-intentioned, but it was a misjudgement.

Paris, a great metropolis of the arts and business, as well as an international communications centre, had all the attractions for Members of the European Parliament, diplomats, and civil servants; Strasbourg, beautiful but provincial, with limited entertainment and above all poorly served, requiring changes of plane to reach its often foggy aerodrome, exercised little charm on the new community population. If the monthly sessions of Parliament – at what cost and for how long? – continue to be held there, everything else, commissions and services, has moved to Brussels and it is Brussels that has become the administrative capital of the Union.

Let us return to Monsieur Bayrou, who is following a fairly typical political path. Elected to parliament, he quickly showed a ministerial appetite by making education issues a specialty. He founded and chaired a permanent group to combat illiteracy. A laudable program. Unfortunately, during the time he was Minister of National Education, illiteracy continued to increase and the general level of education continued to decline. Was it during this period that he experienced a somewhat excessive expansion of his ego?

It is said that one night he woke up the members of his cabinet, urgently summoning them to the ministry, to consult them on a vision he had just had of his presidential future. The anecdote has been circulated with too much insistence for there not to be, at its origin, some reality.

Why am I dwelling so long on Monsieur Bayrou, when we have concerns that seem to be of greater importance? It is because, not content with creating disorder in our domestic policy, he is currently acting contrary to the interests of France in the European Parliament.

Monsieur Bayrou is a candidate for the presidency of the Republic: we know that. He has made it known urbi et orbi and, stubbornness being in his nature, there is every reason to believe that he will be one for life. He also ran in 2002 and, having arrived at the back of the pack, with 6.8%, he immediately put on the jersey with the bib number marked 2007.

Assuring that he is part of the majority in the National Assembly in order to keep his electorate, he keeps his parliamentary group on the fringes, under the pretext of refusing corporatisation; he never stops criticizing the government’s actions, often using the opposition’s arguments, and only votes for it with his fingertips, when he does not abstain, visibly waiting for its fall. Beautiful political logic! This is what Monsieur Bayrou calls cultivating one’s difference. When one benefits from such great support, one ends up preferring adversaries.

His programme? It is made up of nothing but worn-out words and formulas that have become hollow from being used too much. It is as if we had returned to the “more just, more humane Republic” of thirty years ago. Everything ages – even demagoguery. […]

What a waste! And all in keeping. Those who stick around François Bayrou for career interests, like those who stay there out of personal loyalty, expose themselves to serious disappointments.

In politics, I have no other criteria than services rendered to the country.

Prince Talleyrand said: “Without wealth, a nation is only poor; without patriotism, it is a poor nation.”

A Prize for the General

France’s Top Military-Literary Prize Awarded to François Lecointre

IT SHOULD surprise no-one that the French Army awards an annual prize for military literature. Since 1995, the Prix littéraire de l’Armée de terre – Erwan Bergot is awarded every year for “a contemporary work of French literature that demonstrates active commitment, of a true culture of audacity in service to the collective whole” and is named in memory of the paratrooper officer, writer, and journalist Erwan Bergot (1930-1993).

This year’s prize has been awarded to Gen. François Lecointre, the former Chief of the Defence Staff who now serves as the Chancellor of the Légion d’honneur.

This year’s prize has been awarded to Gen. François Lecointre, the former Chief of the Defence Staff who now serves as the Chancellor of the Légion d’honneur.

A graduate of Saint-Cyr, Lecointre’s book Entre Guerres (Between Wars) relays his long service to France in the land forces, including operations in Central Africa, Rwanda, Bosnia, the First Gulf War, and elsewhere.

As a young captain in Bosnia, Lecointre was concerned when his company lost radio contact with the French UNPROFOR observation post on Vrbana bridge early on the morning of 27 May 1995. When he went himself to investigate, Captain Lecointre discovered that Bosnian Serb soldiers in captured French uniforms had seized the post and taken French soldiers hostage.

Lecointre immediately informed Paris, where President Jacques Chirac circumvented the UN chain of command in Bosnia by allowing soldiers under Lecointre’s command to retake the post on the northern end of the bridge with a bayonet charge that overran the Serb-held bunker. Vrbana bridge is believed to have been the last bayonet charge of any French military operation to date.

General Pierre Schill, Chief of the Army Staff, awarded his comrade-in-arms the Prix Erwan Burgot this weekend. The prize includes a monetary award of €3,000 which Gen. Lecointre has donated to the association Terre Fraternité that provides support to France’s wounded soldiers and their families.

Entre Guerres had already won the Prix Jacques-de-Fouchier awarded by the Académie française earlier this year. (Above: Gen. Lecointre with the académicien, lawyer, and writer François Sureau.)

The Erwan Burgot prize’s jury was chaired by Gen. Schill and included the son and widow of Erwarn Burgot, alongside Col. Loïc de Kermabon, Col. Noê-Noël Uchida, the journalist and writer Guillemette de Sairigné, literary figure Laurence Viénot, Général de Division Jean Maurin, Général de Brigade Gilles Haberey, prix Goncourt winning novelist Andreï Makine, writer Christine Clerc, former head army medic Dr Nicolas Zeller, journalist Jean-René Van Der Plaetsen, Professor Arnaud Teyssier, and the historian François Broche.

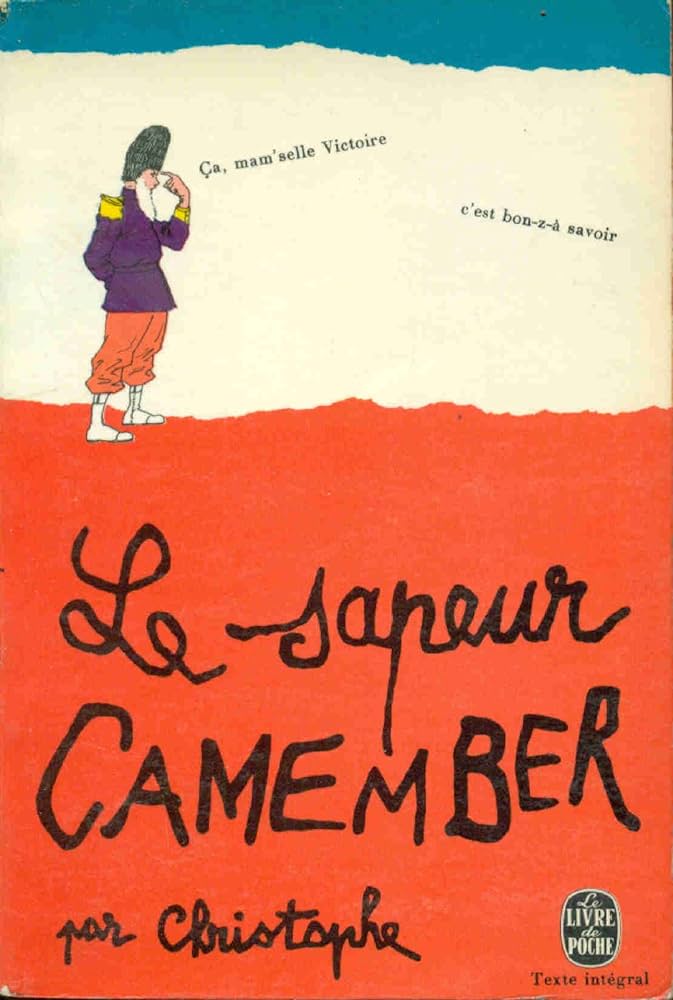

La Bougie du sapeur

Lo, the Twenty-Ninth of February is upon us, which means another edition of the French newspaper La Bougie du sapeur. The printing of a newspaper is not often news itself, for most are dailies and some are weeklies. That rara avis, the fortnightly is — like the monthly — more common amongst magazines. But La Bougie du sapeur is unique in the world as it only comes out on this date, the once-every-four-years leap day. (Or, as the French foppishly put it, bissextile.)

This is the twelfth number of La Bougie, an amazingly indolent feat for a newspaper that began in 1980. Perhaps they take their inspiration from the venerable and beloved Académie française, which was given the task of drafting the dictionary of the French language back in the 1680s, and finally reached midway through the letter “E” in 1992.

The  paper’s name translate as the Sapper’s Candle (for those outside of Angledom, “sapper” is another word for a soldier in the engineers). The soldier in question is Sapeur Camember, a stock character of French comic strips popularised by “Christophe” (Marie-Louis-Georges Colomb) in the pages of Le Petit Français illustré between 1890 and 1896.

paper’s name translate as the Sapper’s Candle (for those outside of Angledom, “sapper” is another word for a soldier in the engineers). The soldier in question is Sapeur Camember, a stock character of French comic strips popularised by “Christophe” (Marie-Louis-Georges Colomb) in the pages of Le Petit Français illustré between 1890 and 1896.

Camember was born on 29 February and thus had only celebrated four birthdays by the time he enlisted in the army. Every leap year thus adds another candle on the sapeur’s birthday cake. The character seeped into the French mind, and there is even a statue of him in Lure.

The newspaper was born in 1980 as a bit of an in-joke between two friends, Jacques Debuisson and Christian Bailly, and Jean d’Indy (pictured above and below) is currently at the helm as editor and director. (His day job is working for the French body responsible for flat racing and steeplechases.)

Ever with an eye on expansion, La Bougie began to print a Sunday supplement in 2004, to appear even more rarely whenever 29 February falls on a Sunday. The next issue of the Dimanche supplement is expected in 2032. This year marks the advent of their sports supplement, La Bougie du sapeur – Sportif.

The tone of La Bougie is satirical, mocking, and politically incorrect — but not without a heart. For example, the profits from the 2008 edition were donated to a charity working amongst autistic adolescents.

Our French readers (we hope they are plural) will want to head out to the kiosk to purchase a copy today, lest they have to wait for the next edition. (more…)

Crisis Averted at Chartres

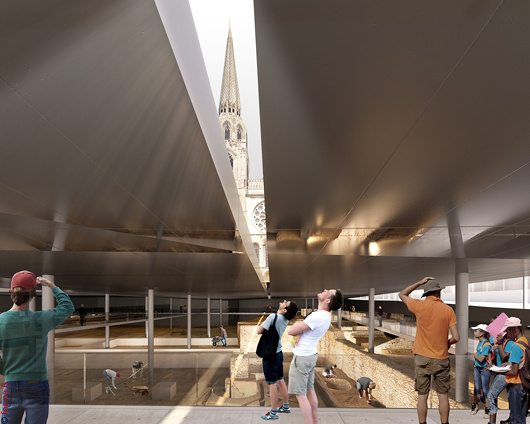

The rather garish and invasive plans to renovate the parvis of Chartres cathedral, turn it upside down, and install a museum underneath — previously reported on here in 2019 — have been radically revised in an infinitely less offensive direction.

The City of Chartres has released the final approved designs which show the esplanade of the cathedral renovated but left largely in place.

Instead of the original plan up reversing the grade of the parvis upwards away from the cathedral, the entire museum will be kept underground and out of sight. (more…)

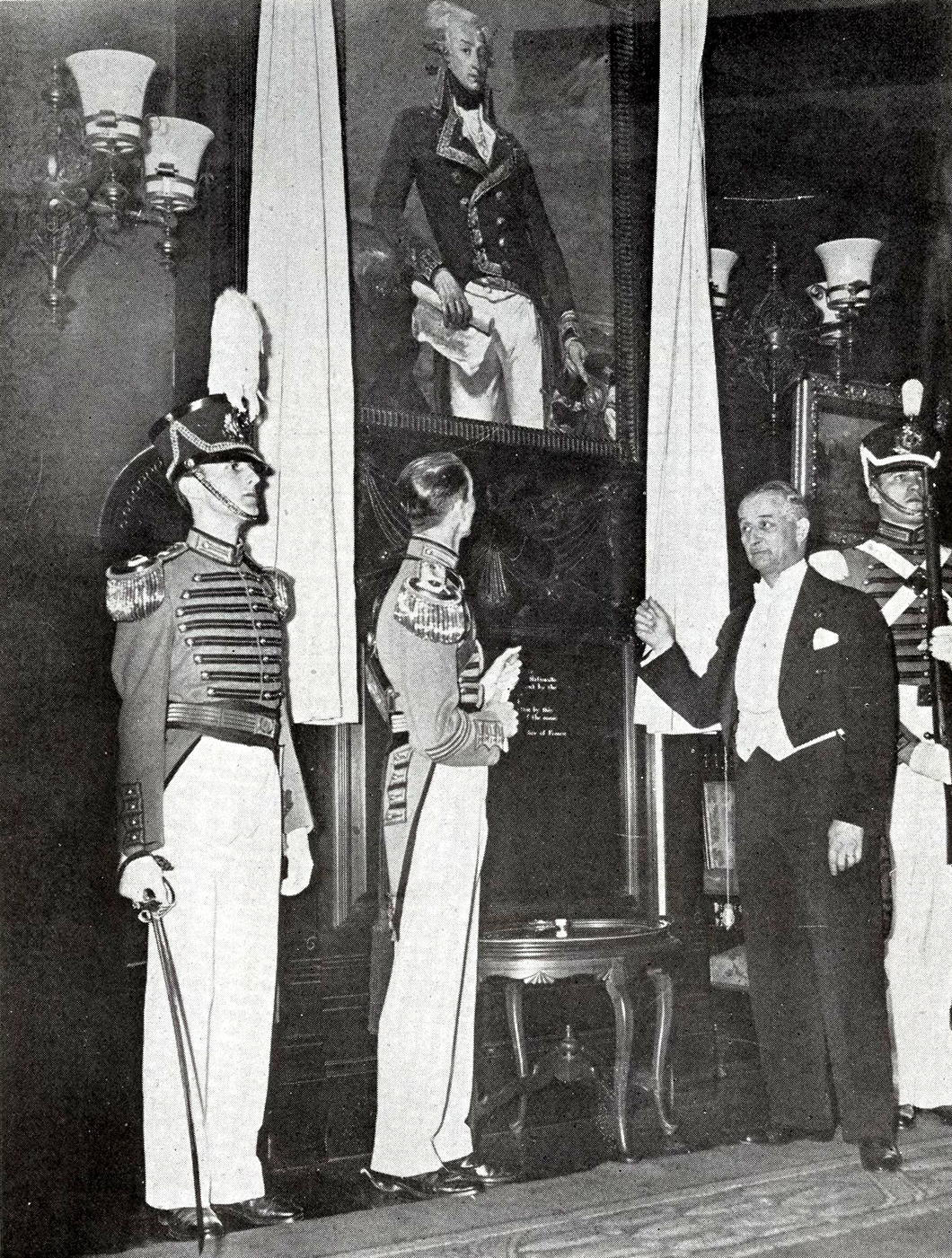

Lafayette at the Seventh

For the first century or so in the history of the United States, there was no more popular Frenchman in America than the Marquis de Lafayette. This nobleman of the Auvergne was an officer in the King’s Musketeers aged 14 and was purchased a captaincy in the Dragoons as a wedding present aged 18 in 1775. Within a year the rebel faction in North America had sent Silas Deane of Groton to Paris as an agent to negotiate support from the French sovereign, but Paris acted cautiously at first.

Lafayette — a young aristocratic freemason and liberal with a head full of Enlightenment ideas — escaped to America in secret and was commissioned a major-general on George Washington’s staff in the last of his teenage years.

Given his relative youth, Lafayette inevitably turned out to be the final survivor of the generals of the Continental Army, and his 1824 trip to the United States solidified his popularity. He visited each of the twenty-four states in the Union at the time, including New York where the predecessor of the Seventh Regiment named itself the National Guards in honour of the Garde nationale Lafayette commanded in France.

This was the first instance of an American militia unit taking the name National Guard, which in 1903 was extended to all of state militia units which could be called upon for federal service.

In honour of this connection and on the centenary of Lafayette’s 1834 death, the French Republic presented the Seventh Regiment with a copy of Joseph-Désiré Court’s portrait of the general that hangs in the 1792 Room of the Palace of Versailles. The Seventh set this in the wall of the Colonel’s Reception Room in their Armory, facing a copy of Peale’s portrait of General Washington.

The privilege of unveiling the portrait went to André Lefebvre de Laboulaye, the French Ambassador to the United States, who was given the honour of a full dress review of the Seventh Regiment on Friday 12 April 1935 before a crowd of three thousand in the Amory’s expansive massive drill hall.

Also present at the occasion was his son François, who eventually in 1977 stepped into his late father’s former role as French Ambassador to the United States. His Beirut-born grandson Stanislas served as French Ambassador to Russia 2006-2008 before being appointed to the Holy See until 2012. In April 2019, Stanislas de Laboulaye was put in charge of raising funds for the rebuilding of Notre-Dame following the fire that devastated the cathedral.

L’Élysée à la plage

The Fort de Brégançon: Riviera Retreat of France’s Presidents

When France’s head of state needs to let his hair down every summer, the Republic has a convenient presidential residence just for him to do so: the Fort de Brégançon on the Côte d’Azur.

There has been a fortress here since at least mediæval times, and Gen. Buonaparte (later emperor) ordered its ramparts renewed after the retaking of Toulon in 1793. It continued to serve military purposes until 1919, but in 1924 it was leased out to a local mercantile family, the Tagnards.

They passed their lease on to the former government minister Robert Bellanger, who improved the island greatly, connecting it to the water and electricity supply, building the causeway linking it to the mainland, and laying out the Mediterranean garden. Bellanger’s leased expired in 1963 and Brégançon returned to the property of the state.

President de Gaulle stayed a night on the island in 1964 but found the bed too small and the mosquitos too bothersome. Nonetheless, his wartime comrade René-Georges Laurin (mayor of Saint-Raphaël up the coast) convinced him it would make a suitable summer residence that befitted the dignity of France’s head of state.

The architect Pierre-Jean Guth was seconded over from the Navy to adapt and update the fort to this end. The rooms are a little small, but their cozy intimacy adds to the fort’s informality. The presidential bedroom features a Provençal bed facing the sea with a view towards the nearby island of Porquerolles.

Pompidou and Giscard enjoyed the island but Mitterand mostly neglected the island except when welcoming Chancellor Kohl and Taoiseach Garrett Fitzgerald. Chirac and his wife took up Brégançon and were often seen by the locals on their way to Mass.

Sarkozy liked to be photographed on his jogs from the island but after he abandoned his wife and took up with his mistress he preferred holidaying at Carla Bruni’s far grander and more comfortable summer residence.

Hollande opened the fort up to public visitors, hoping to recoup some of the costs of maintaining the property. Macron has taken to the island frequently for his summers, for meetings with foreign leaders, and for working weekends with his ministers.

With summer fires raging, a minority in parliament, and myriad other problems brewing, no doubt Macron has much on his agenda.

All the same, for France’s sake, we can’t help but hope Monsieur le Président has a happy holiday. (more…)

30 mai 1968

The events of May 1968 have been fetishised by the romantic radical left but ended in the triumph of the popular democratic right. Battered by two world wars, France had enjoyed an unprecedented rise in living standards since 1945 — especially among the poorest and most hard-working — and a new generation untouched by the horrors of war and occupation had risen to adulthood (in age if not in maturity). The ranks of the middle class swelled as more and more people enjoyed the material benefits of an increasingly consumerised society, while those left behind shared the same aspirations of moving on up.

Like any decadent bourgeois cause, the spark of the May events was neither high principle nor addressing deep injustice but rather more base impulses: male university students at Nanterre were upset they were restricted from visiting female dormitories (and that female students were restricted from visiting theirs). The ensuing events involved utopian manifestos, barricades in the streets, workers taking over their factories, a day-long general strike and several longer walkouts across the country.

The French love nothing more than a good scrap, especially when it’s their fellow Frenchmen they’re fighting against. Working-class police beat up middle-class radicals but for much of the month both sides made sure to finish in time for participants on either side to make it home before the Métro shut for the evening. But workers’ strikes meant everyday life was being disrupted, not just the studies of university students. When concessions from Prime Minister Georges Pompidou failed to calm the situation there were fears that the far-left might attempt a violent overthrow of the state.

De Gaulle himself, having left most affairs in Pompidou’s hands, finally came down from his parnassian heights to take charge but then suddenly disappeared: the government was unaware of the head of state’s location for several tense hours.

It turned out the General had flown to the French army in Germany, ostensibly to seek reassurance that it would back the Fifth Republic if called upon to defend the constitution. De Gaulle is said to have greeted General Massu, commander of the French forces in West Germany, “So, Massu — still an asshole?” “Oui, mon général,” Massu replied. “Still an asshole, still a Gaullist.”

The morning of 30 May 1968, the unions led hundreds of thousands of workers through the streets of Paris chanting “Adieu, de Gaulle!” The police kept calm, but the capital was tense and there was a sense that things were getting out of hand. Pompidou convinced de Gaulle the Republic needed to assert itself.

Threatened by a radicalised minority, de Gaulle called upon the confidence of the ordinary people of France. At 4:30 he spoke on the radio briefly, announcing that he was calling for fresh elections to parliament and asserting he was staying put and that “the Republic will not abdicate”.

Before the General even spoke some his supporters (organised by the ever-capable Jacques Foccart) were already on the avenues but the short four-minute broadcast inspired teeming masses onto the streets of central Paris, marching down the Champs-Élysées in support of de Gaulle.

Anglo-Gaullist Reading Update

The latest round of news or commentary of Gaullist content or interest:

Mercator: Charles de Gaulle: a wise ruler of France

Financial Times: France invokes the golden age of de Gaulle

Politico: Why all French politicians are Gaullists

Variety: Cliché-Ridden ‘De Gaulle’ is Unworthy of Its Iconic Subject

Problems and Solutions

There are in some periods problems to which no solutions exist.”

An Interview with Philippe de Gaulle

Last year, in advance of the Admiral’s ninety-ninth birthday and the fiftieth anniversary of his father’s death, Paris Match sent Caroline Pigozzi to interview Philippe de Gaulle.

What follows is an abridged and completely unofficial translation of what Admiral de Gaulle insists will be his “last interview”.

ADMIRAL PHILIPPE DE GAULLE: Everyone has appropriated their share, even the Communists. All those who refer to General de Gaulle’s policy respect his Constitution, that of the Fifth Republic…

But, over the elections, my father’s imprint has faded. Pompidou, he was not quite his ideas anymore. Giscard d´Estaing, even less so… Mitterrand, basically, had the ideas of General de Gaulle, but he could not say it.

How do you judge the current president?

Emmanuel Macron is quite right to reference himself to the General as well as to other heads of state — France comes from the depths of the ages and the centuries call for it.

However, he is too involved in parliamentary life: the president should have a little more perspective. But anyway, it’s a Gaullist talking to you! The head of state is above Parliament and the government he appointed. It’s up to them to discuss day-to-day business. He has a prime minister who has to fight every day with his ministers and with Parliament.

And it’s up to the president, of course, to give direction, to choose. It is his “job”, just like dealing with the health crisis, which cannot stand any delay.

Which annual ceremonies have marked you the most?

The parade of 14 July, a commemoration of real scale which bears witness to the victories of the Republic.

My father would have liked to have celebrated on November 1 and 2 [All Saints’ and All Souls’ days] the remembrance of all war dead, for families, but that there were no other commemorations.

Why continue indefinitely with November 11, which marks the armistice of 1918, and May 8, the victory of 1945? Leave the public holidays to which the French are so attached, and let the state stick to these two dates.

Did your father like sports?

It was very important for him, because it marked the vitality of France. In his eyes, a country that had no athletes was a country half-dead.

Did he read the press?

He watched the news every night — it interested him to see what the French saw.

And, of course, he read Paris Match every week. I’m not saying that to flatter you: your newspaper is the only one that reported on La Boisserie during his lifetime.

He also read the dailies, even [the Communist] L’Humanité, but not always Le Monde, which he called for a time L’Immonde [“the foul”].

Do you know that it was de Gaulle who founded it? We do not mention it, but it’s the truth! Just after the war, in his office in rue Saint-Dominique, he asked Pierre-Henri Teitgen, Minister of State for Information, to find a journalist with a resistance background and recognised competence. The name Hubert Beuve-Méry was put forward.

My father summoned him: “You are going to make a newspaper like Le Temps before the war, which is politically neutral and with columnists. I’ll give you the money and the paper.

The first issue didn’t mention the General; in the second they started writing against him. In fact, Beuve-Méry never stopped running a pro-Fourth Republic daily, criticizing de Gaulle…

In another style, later on, my father discovered “Tintin” and “Asterix” thanks to my children, immersed in these readings during their vacations in Colombey.

Why was your mother known colloquially as “Aunt Yvonne”?

It was a nickname, as it sounded like Becassine. The truth is, people initially thought she was clumsy or frumpy. She wore her hair in a bun then, never interfering in anything.

She would go to see nuns for her charitable work, but on condition that no reporter showed up. Otherwise, she would turn right around.

You have never heard my mother speak of her charitable work, although she was devoted to it all her life! Sometimes I went with her. One day, with her, with nuns caring for hearing-impaired boys aged 4-5, the sisters played the piano for them and they put their little heads close to the keyboard. Poor people!

My mother had a knack for tackling little-known causes. She ended her life in the retirement home of the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception in Paris. There she was sure the nuns would neither speak to nor receive journalists.

Did the General use the familiar form “tu” easily?

He said “vous” to women, “tu” was more often used for regimental comrades. But he never used the familiar with men, out of a sense of honour. Not even the Companions of the Liberation! How could he have said “tu” to a soldier? People who fight, risk their lives, deserve a certain dignity. Even if they are not worthy elsewhere…

My father vouvoyer-ed my two sisters, used “tu” with my sons, but not his granddaughter. My sister and I vouvoyer-ed our mother, and she tutoyer-ed all of us.

As for my father with his wife, sometimes he was formal, sometimes he was familiar — but in public it was generally “vous”. Me, he was familiar with me and I used “tu” with him.

Your father should have made you a Companion of the Liberation.

He hesitated and said to me, “After all, you were my first companion.”

I replied: “Not the first, the second after your aide-de-camp, Geoffroy de Courcel.”

“Yes, but I cannot name you companion, because then I would have to name three times as many and I cannot do it. Everyone will know that you were one of my first companions.”

(The admiral, his voice charged with emotion, will say no more.)

The last companion of the Liberation will be buried in the crypt of Mont Valérien.

This is the rule they drew up, and the General endorsed it. They settled it a bit like the Marshals of the Empire — when the Companions were united with their first chancellor, Admiral Georges Thierry d’Argenlieu, a monk-soldier who then returned to the Carmel under the name of Father Louis de la Trinité.

After the war, they chose to commemorate the Appeal, every June 18, outside the official state — that is to say not at the Arc de Triomphe but at Mont Valérien, where more than a thousand hostages and resistance fighters had been shot. They erected a wall and a crypt, the Fighting France Memorial, and decided that the last of them would rest there.

Of the 1,038 who received the Order of Liberation, including 271 posthumously, they are now only three: Pierre Simonet, 99 years old, formerly a soldier, Daniel Cordier, centenarian, former secretary of Jean Moulin then merchant of art, and Hubert Germain, the dean of the order, also a hundred years old, who was deputy then minister under Georges Pompidou. He was supposed to join the navy with me and I found him on the “Courbet”, but he ultimately didn’t want to be a sailor anymore.

My father created the order on 16 November 1940 to reward individuals, civilian and military units, and civilian communities working to liberate France. He maintained a special bond with his Companions from all walks of life and from all political parties, even the Communist Party…

[Hubert Germain, the last Companion, died earlier this year and was buried at Mont Valérien after being recognised with full honours at Les Invalides.]

Father Euvé, the Jesuit who heads the prestigious review Etudes, explains that the Society of Jesus educates people for great destinies.

No less than two presidents under the Fifth Republic: de Gaulle and Macron!

It is clear that the Jesuits teach the meaning of the state and how to present oneself. Emmanuel Macron, a former student of La Providence in Amiens, a Jesuit institution, indeed has this talent.

Certainly he should speak a little more briefly, but he presents himself well and he is young. For me, he has not exhausted his full potential… And if he goes, who will be there? Tell me! I don’t see anyone else at the moment.

But back to the Jesuits, where my father studied. As a kid, I was in Saint-Joseph in Beirut, but it was the nuns who took care of us. Charles de Gaulle, on the other hand, attended the College of the Immaculate Conception, rue de Vaugirard, in Paris, which is now closed. His father taught there and was even its lay director after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1901.

What a training! You should know that when a seminarian enters the Jesuits, he begins his studies again for nine years. Jesuits have a taste for the state and a sense of power. They educate people for administration, science, exploration, astronomy… So it’s important first, I stress, to know how to present yourself. Thus, the theater, rich in lessons, helps in this.

Was the General’s piety one of their legacies?

For him, life did not exist without the Creator. He could not believe in a universe that emerged out of pure chance and found the Catholic religion to be the most human, the most balanced, the one that accompanied you best until the end, and that had given rise to the most sacrifices and dedication.

The General had a deep fervour throughout his existence, with great Christian roots, marked among others by the readings of Jacques Maritain and Charles Péguy, and also by the Jesuits. It corresponded to an intimate devotion, to an interiorisation of his faith, that of a being active in the world who did not keep his baptismal certificate in his pocket.

Doesn’t France have centuries of Christianity behind it? However, in the courtyard of the Elysée, laïcité oblige: there was no waltz of cassocks.

On the other hand, remember, in 1946 it was picturesque to see, for example, Canon Kir and Abbé Pierre sitting amidst the benches of the National Assembly.

Nevertheless, men of God must be concerned with the spiritual and, in a certain way, the social.

Admiral, tell us about your second professional life.

Indeed, from September 1986 to September 2004, I was in the Senate for the RPR and then elected a UMP city councillor in Paris.

Chirac had come to get me for the municipal elections. We campaigned all over the capital and, on March 6, 1983, he snatched eighteen out of twenty arrondissements!

It was until I was 84 — the age at which my maternal grandfather died, which at the time seemed very old to me — that I was a senator for Paris. Although the cliché of the senator dozing after meals is outdated, it was no longer the navy when I was constantly running around. An admiral is a fellow who moves from boat to boat, day and night.

How did you experience the lockdown?

I haven’t been out at all but, as I’ll be 99 soon, that doesn’t really matter! It was sometimes awkward to get to the bank or run an errand as I’m now a widower on my own.

I can’t walk anymore. Taking five steps one way and five the other, your knees are rusting. Many old people are dead, masked, “emblousinés”.

My children brought me fruit but it had to be put in a bag — it was all very compartmentalised.

And how is your daily life going now?

When everything is going well, I get visits from time to time from my family — my four sons gave me six grandchildren and two great grandchildren.

I read a lot of history books; I answer a lot of the mail that mostly comes from the descendants of Free French people. I listen to classical music, I watch the big games of tennis, rugby, football on television.

And also the James Bond films, films by Melville, Louis de Funès like ‘Le Petit Baigneur’, westerns, and documentaries on animals, nature with its distant landscapes, deserts, the Far North… There are magnificent places, countries where I have not been and where I will never go: Mongolia, the Himalayas… I only did mountaineering on screen. (He laughs.)

Was the cinema one of the General’s rare “distractions”?

He liked to see films, pre-war comedians and great actors such as Charles Boyer, Fernandel, Louis de Funès… He also liked Michèle Morgan, whom he found quite jolie, with a lot of allure, acting well.

At the Elysée Palace, having little time, he mainly watched the news. This had led to some myths, such as that of an announcer who was said to have been kicked out because my mother thought it was inappropriate for her to show her knees. Completely ridiculous! My mother did not get involved in this, especially since those in the audiovisual sector were more for de Gaulle, while the print media were often against him.

Has President Macron come to visit you, a few days before this historic anniversary?

Why would he do that? Be serious: he has no time to waste! He already sees far too many people and, at almost 99 years old, you are just a vestige of yourself.

[But on this, Admiral de Gaulle’s 100th birthday, President Macron has issued a communiqué.]

A vestige with the great pride of being called de Gaulle!

I admit I found it heavy, but hey, that’s how it is. We don’t choose such things. Carrying this name hindered my own freedom, constrained me to a lot of discretion. Besides, I joined the navy so as not to be in the army, where I would have had an impossible life. The navy is looking out to sea!

Lastly: write it down that this is my last interview. I insist! I am now too old for that. And don’t tell my sons that I gave you an interview. I’ll have to tell them that it was you who caught me, “caught” me. So, thank you for the photos, the historic Paris Matches and the cake. I shouldn’t eat cake anymore… At my age, sugar isn’t very good!

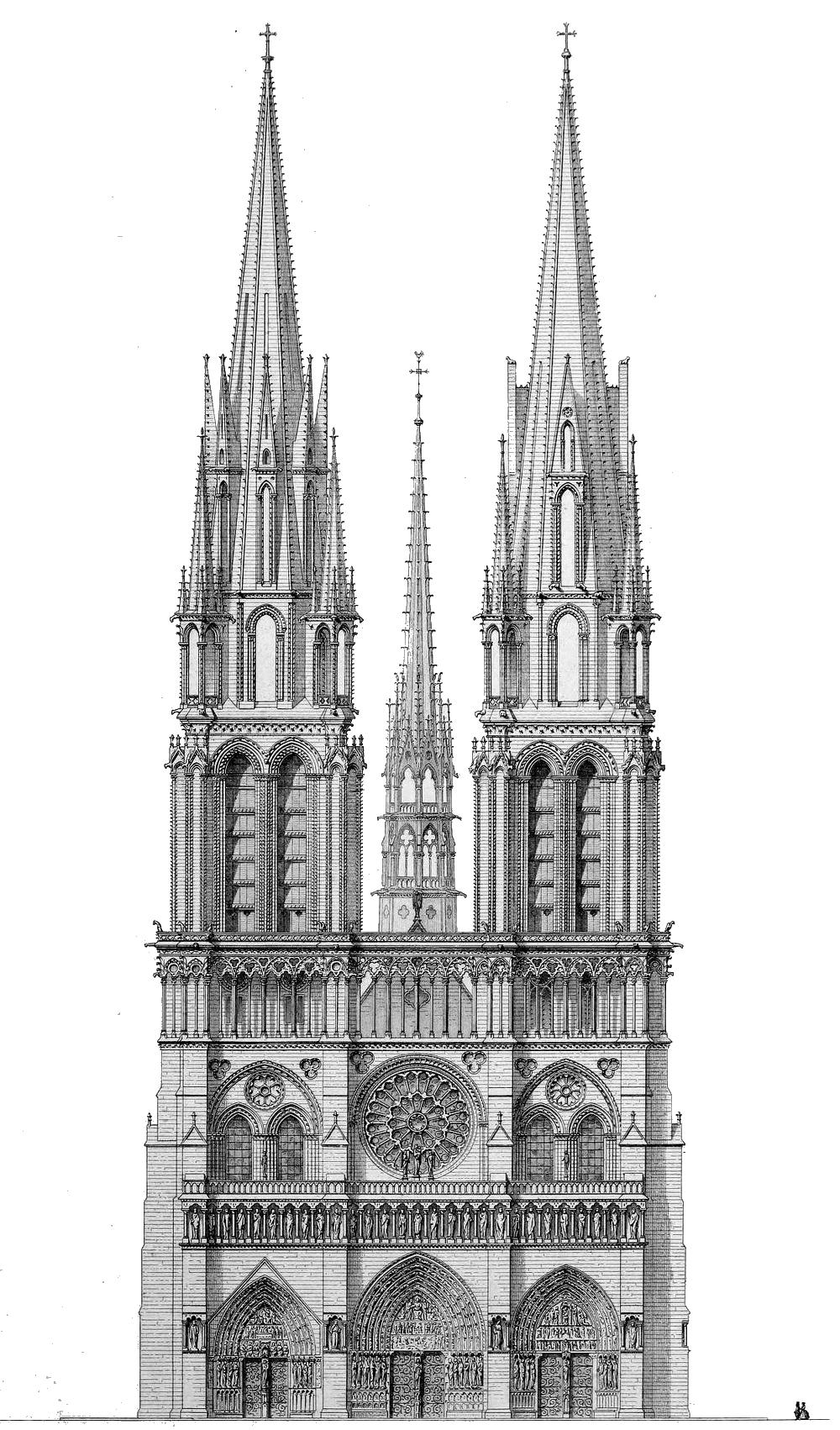

Notre-Dame de Paris

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

1844

Chartres Disfigured

Plans for modern monstrosity in venerable cathedral’s forecourt

MORE BAD NEWS from Chartres. Fresh from the completion of a controversial and much criticised renovation of the ancient cathedral’s interior, le Salon Beige reports the city has unveiled plans to tear up the parvis in front of the cathedral and replace it with a modernist “interpretation centre”.

The original parvis (or forecourt) was much smaller than the one we know today. Between 1866 and 1905 the majority of the block of buildings in front of the cathedral, including most of the old Hôtel-Dieu, were demolished to give a wider view of the cathedral’s west façade and its “Royal Portals”.

After the war various plans to tart the place up were made and variously foundered — from a modest alignment of trees in the 1970s to Patrick Berger’s plan for an International Medieval Centre. More recently the gravelly space was unsuccessfully “improved” by the addition of boxes of shrubbery placed in a formation that, jarringly, fails to align with the portals of the cathedral.

The proposed “interpretation centre” designed by Michel Cantal-Dupart — at a projected cost of €23.5 million — destroys the gentle ascent to the cathedral and indeed reverses it. At a projected cost of €23.5 million, a giant slab juts apart as if displaced by an earthquake. The paying tourist is invited down into its infernal belly while others prat about on the slab’s upwardly angled roof, ideal for gawking at the newly commodified beauty of this medieval cathedral. It is practically designed for Instagramming, rather than reflection and contemplation.

As you would imagine, reaction has been strong. Michel Janva, writing at le Salon Beige, says the project “plans to imprison the cathedral” and “will disappoint not only pilgrims on their arrival, but also inhabitants and tourists”.

In the Tribune de l’Art, Didier Rykner is damning: “All this is purely and simply grotesque.” The sides of the centre, he points out, will be glazed to allow in natural light, but this will both interfere with multimedia displays and be bad for the conservation of fragile works of art. “This architecture, which looks vaguely like that of a parking lot, is frighteningly mediocre, and this in front of one of the most beautiful cathedrals of the world.”

Rykner attributes blame for the “megalomaniac and hollow project, expensive and stupid” at the doors of the mayor of Chartres, Jean-Pierre Gorges, who he argues has allowed much of the rest of the city’s artistic and architectural heritage to go to rot while devoting resources to this pharaonic endeavour.

Having walked from Paris to Chartres myself I can imagine how much this proposal will injure the experience for pilgrims. After three days on the road, to arrive at Chartres, stand in the parvis, and gaze up at this work of beauty, devotion, and love for the Blessed Virgin is a profound experience. If constructed, this plan would deprive at least a generation or two from having this experience. (But only a generation or two, for it is simply unimaginable to think this building will not be demolished in the fullness of time.)

Chartres is part of the patrimony of all Europe and one of the most important sites in the whole world. For it to be reduced to the plaything of some momentary mayor is a crime. With any luck, the good citizens of Chartres, of France, and of the world will put a stop to this monstrosity. (more…)

Roots and Permanent Interests

The French Way of War

I’ve  been reading Lartéguy recently so was intrigued to hear of another French writer formed by his military experience, Pierre Schoendoerffer (right).

been reading Lartéguy recently so was intrigued to hear of another French writer formed by his military experience, Pierre Schoendoerffer (right).

In a tweet, the cigarette-smoking Helen Andrews shared an article called What a 1963 Novel Tells Us About the French Army, Mission Command, and the Romance of the Indochina War.

I dislike the romanticism surrounding the magnificent losers vs. ugly victors dichotomy – a magnificent victory is infinitely preferably to both. Hence why my natural Jacobite sympathies are highly qualified by complete and utter disdain for Charlie’s unwillingness to see the task through. (An easy judgement when made from centuries of hindsight, I’ll concede.)

Anyhow, I sent the article to The Major and he proffered this reply:

I was going to say something snide about the French army but to be quite honest I have thought for some time that it is rather better than ours [Ed.: the British]. Their officers are tougher, harder, and more professional than ours – those I encountered professionally certainly were. They are also not infected by the political correctness which is wrecking/has wrecked our army (among other factors).

The distinction between the colonial army and the large conscript army at home is valid. It was the conscript army which was defeated in 1870, 1914, and 1940… not the colonial army to which the modern French army now looks.

It is also true that the US Army don’t do Mission Command well. The Marines on the other hand…

Meanwhile back in the States the prolific Ken Burns has done an eighteen-hour documentary on the Vietnam conflict which allegedly ignores all the scholarly input of the past two decades. Nevermind, we just regret it won’t feature the late great Shelby Foote, who (in Burns’s ‘The Civil War’) spoke with such assurance you imagined he was there.

Fillon: Which Right?

A Rémondian Analysis of the French Presidential Candidate

One of the most significant contributions of the historian and political scientist René Rémond was his theory regarding the tendencies of the French right wing. He contended that, broadly speaking, there are three right wings in France: legitimist, bonapartist, and orleanist. These terms are not bound by their historic use, but rather (Rémond argued) serve as useful guides to understanding French conservatism today.

Gaullism, for example, with both its populism and its reliance on the authority of a charismatic leader, is classified as bonapartist. Social conservatism, meanwhile, with its affinity for the Church and for tradition, comes in under legitimism. And economic liberalism — the bourgeois supremacy of the markets — is orleanist.

What to make of the current presidential candidate of the French right, M François Fillon? The Québécois website Dessinons les élections (“Let’s draw the elections”) sought to apply a Rémondian analysis of Monsieur Fillon in one of its weekly cartoons (by Frédéric Mérand & Anne-Laure Mahé).

Their conclusions are as follows:

Legitimism: 60%

– social conservatism

– Christian values

– order and traditionOrleanism: 30%

– economic liberalismBonapartism: 20%

– a sense of the State

– idea of the providential man with reference to de Gaulle

Of course, many now think that, due to the usual scandals, Fillon is yesterday’s man and that Macron is the man of the hour. The two are chalk and cheese. Fillon is the family man from the country, loves hunting, and clings to the values of the Church. Macron is a socialist énarque and investment banker who married one of his school teachers (twenty-four years his senior).

The elephant in the room: Madame Le Pen. The leader of the Front national will, there is almost no doubt, top the first round of the election but then, in the second round, will have to face whichever other candidate gains the next highest number of votes. Whoever that candidate is will almost certainly gain all the anti-frontiste votes and be propelled to victory and the Elysée.

At the moment, it looks like the second candidate will only have to win around 22 per cent of the vote in order to effectively gain the presidency. Such a low level of actual support is one of the things the 1962 changes to the constitution sought to prevent, but when faced with an FN candidate as in 2002 or (presumably) this year the two-round system fails to prevent this.

As usual, the conservatives are calling for change and the progressives arguing for stasis, but it remains to be seen which option France will choose.

The slums of the Louvre

We are so used to the now-familiar image of the palais du Louvre — with its central wing and flanking arms wide open to the Jardin des Tuileries — that it’s easy to forget just how recent a creation this ensemble is. The palace began as a square chateau expanding upon the site of the medieval citadel. The Tuileries it eventually stretched towards was then an entirely separate palace. In-between the Louvre and the Tuileries was a whole neighbourhood of buildings, streets, alleyways, and squares.

Henri IV built the grande galerie on the banks of the Seine connecting the Old Louvre to the Tuileries by 1610, but the Louvre we know today really only came together under Napoleon III in the 1850s.

Until that point, a slum was built right up to the walls of the Palace, and even within the old courtyard. Balzac, predicting that one day all this would be cleared, noted the slum with amusement as “one of those protests against common sense that Frenchmen love to make”. (more…)

The Death of God the Father

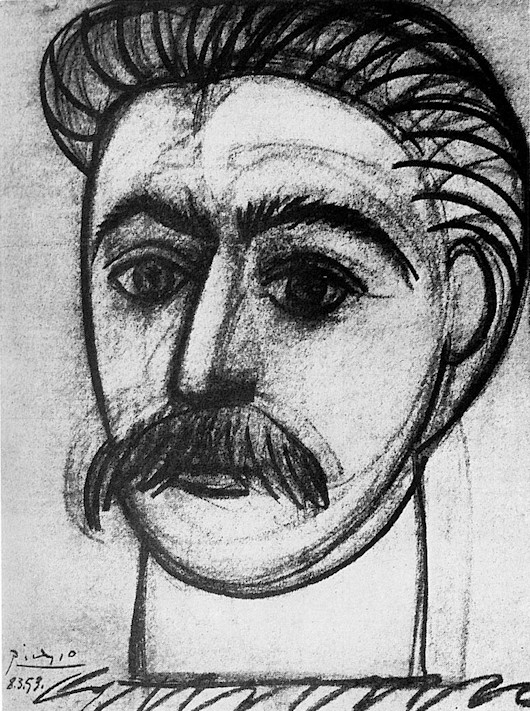

When Stalin’s death was announced on Friday, 7 March 1953, Aragon called in Pierre Daix and rattled off a shopping list of features to honour Stalin in a special issue of Les Lettres françaises. […] Since Picasso had always refused to do a portrait of Stalin from a photograph, Daix sent a telegram to him at Vallauris saying, ‘Do whatever you want,’ and signed it ‘Aragon’.

Picasso’s drawing of Stalin, which depicted him as a curiously open-eyed young man, arrived at the very moment Les Lettres françaises went to press. Daix took the picture to Aragon. He admired it and said that the party would appreciate the gesture. While it was being set into the front page, office boys and typists crowded round the picture. Everyone thought it ‘worthy of Stalin’.

Daix was overjoyed to be the one who had commissioned Picasso’s first portrait of the Soviet leader and rushed it down to the printers. But a few hours later, when the edition had been run off, the mood in the building had completely changed to one of fear. Journalists from L’Humanité, passing by, spotted the drawing and cried out that it was unthinkable that any Communist publication should consider such a representation of ‘le Grand Staline’.

Pierre Daix promptly rang Aragon at his apartment; Elsa Triolet answered. She told him angrily that he was mad to have even thought of asking Picasso for such a drawing.

‘But really, Elsa,’ Daix broke in, ‘Stalin isn’t God the Father!’

‘Yes, he is, Pierre. Nobody’s going to reflect much about what this drawing of Picasso signifies. He hasn’t even deformed Stalin’s face. He’s even respected it. But he has dared to touch it. He has actually dared, Pierre, don’t you understand?’ […]

Antony Beevor & Artemis Cooper (1994, London)

Fête Chiracienne

AS TODAY IS the eighty-fourth birthday of Monsieur Jacques René Chirac, I thought it’d be best to share a few images of the underappreciated fifth president of the Fifth Republic (not to mention sometime Mayor of Paris, Prime Minister of France, and Co-Prince of Andorra) doing the things he does best. (more…)

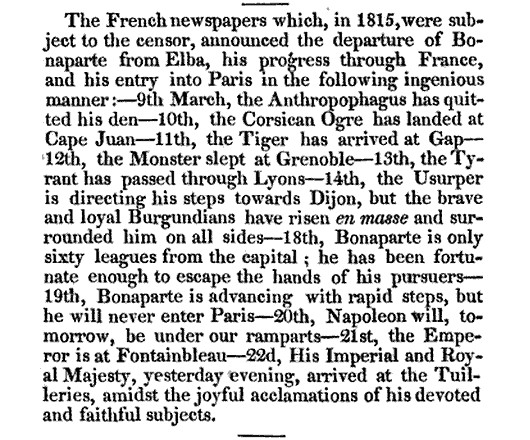

The Anthropophagus Has Quitted His Den

The Museum of Foreign Literature Science and Arts was a Philadelphia periodical edited by the prodiguously talented and unjustly neglected Eliakim Littell.

In January 1831 his review published this little snippet of headlines claimed to have been clipped from French newspapers:

The French newspapers which, in 1815, were subject to the censor, announced the departure of Bonaparte from Elba, his progress through France, and his entry into Paris in the following ingenious manner:

March 9 THE ANTHROPOPHAGUS HAS QUITTED HIS DEN

March 10

THE CORSICAN OGRE HAS LANDED AT CAPE JUAN

March 11

THE TIGER HAS ARRIVED AT GAP

March 12

THE MONSTER SLEPT AT GRENOBLE

March 13

THE TYRANT HAS PASSED THOUGH LYONS

March 14

THE USURPER IS DIRECTING HIS STEPS TOWARDS DIJON

but the brave and loyal Burgundians have risen en masse

and surrounded him on all sidesMarch 18

BONAPARTE IS ONLY SIXTY LEAGUES FROM THE CAPITAL

He has been fortunate enough to escape the hands of his pursuersMarch 19

BONAPARTE IS ADVANCING WITH RAPID STEPS

But he will never enter ParisMarch 20

NAPOLEON WILL, TOMORROW, BE UNDER OUR RAMPARTS

March 21

THE EMPEROR IS AT FONTAINEBLEAU

March 22

HIS IMPERIAL & ROYAL MAJESTY, yesterday evening, arrived at the Tuileries, amidst the joyful acclamation of his devoted and faithful subjects.

Voltaire’s Works Are Not Dead

They Are Alive: And They Are Killing Us

“It was a little after nine in the evening; the sun was setting, the weather superb. … Nothing is rare, nothing is more enchanting than a beautiful summer evening in St Petersburg. Whether the length of the winter and the rarity of these nights, which gives them a particular charm, renders them more desirable, or whether they really are so, as I believe, they are softer and calmer than evenings in more pleasant climates.”

The Soirées Saint-Petersbourg of Joseph de Maistre are philosophical dialogues that sometimes border on the mystical and delve into the dark recesses of human nature. They are eloquent, fascinating, and beautiful, traversing a broad range of subjects while hovering around evil and why it exists in the world.

In this extract from the Fourth Dialogue, the Count — generally taken to represent the author’s own view — objects to the young Chevalier citing Voltaire approvingly.

A critic might call it a rant; if so, it is at least a beautiful one:

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories