Austria

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

God and the Emperor

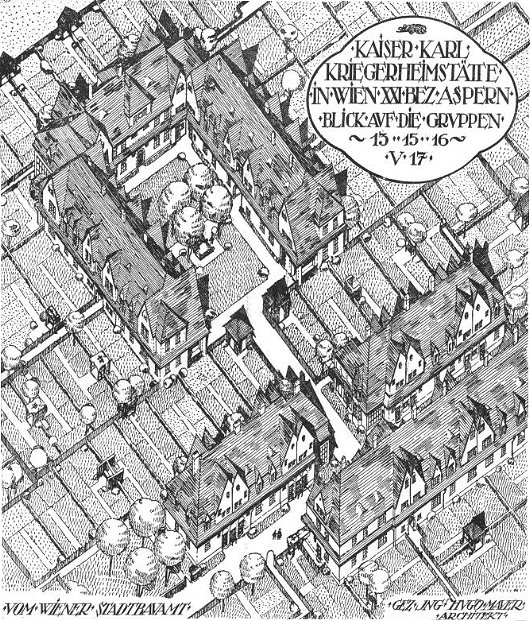

The Kaiser Karl Soldiers’ Homes

An unexecuted design. The architect later designed a number of housing projects during the First Austrian Republic.

The Coronation of Blessed Charles

Blessed Emperor Charles was crowned as Apostolic King of Hungary on the 30th of December in 1916. It was the last Hapsburg coronation to this day. For those interested there are two accounts which do justice to the sacred rites. One is by that most devoted admirer of the Hapsburgs, Gordon Brook-Shepherd, in his excellent biography of Charles, The Last Hapsburg. (Brook-Shepherd also wrote excellent and quite readable biographies of the Empress Zita, of Crown Prince Otto, of Chancellor Dollfuß, and Baron Sir Rudolf von Slatin Pasha).

Charles & Zita

October 21 was chosen as the Feast of the Blessed Emperor Charles not because it is the date of his death — which is 1 April 1922 — but rather to commemorate the marriage (photo, below) between Archduke Charles of Austria (as he was then) and Princess Zita of Bourbon-Parma in 1911. While Charles died a mere thirty-four years of age, Zita lived on to ninety-six before passing away in 1989 (when I myself was four).

Not very long ago I was in Quebec City, which was where the Empress Zita and the Imperial Family spent their exile during the Second World War. The Hapsburgs, dispossessed first by the Socialists and then by the Nazis, were then so poor they had to collect dandelions from which to make a soup, but they took poverty in their stride. Passing a grassy bit near the Chateau Frontenac, I wondered “Did Crown Prince Otto once pluck weeds from this plot to feed his hungry mother and siblings?”

Also in that ancient Canadian city is La Citadelle, that great hunk of stone and earthworks, perhaps the oldest operational military installation in the New World. There we were lucky enough to be granted access to the tomb of the greatest Canadian, Major General the Rt. Hon. Georges-Philéas Vanier, Governor-General of Canada from 1959 until his death in 1967. General Vanier and his wife had such a reputation for Christian charity and piety that the Vatican is collecting evidence towards their eventual recognition as saints. Their son is Jean Vanier, the founder of the famous l’Arche communities that care for the handicapped and the disabled. I wonder if the Hapsburgs and the Vaniers ever crossed paths in wartime Quebec…

pray for us!

Words of Windisch-Grätz Wisdom

Prince of Windisch-Grätz

on the liberal constitutionalist rebels

‘The man who walked’

The Daily Telegraph — 6 September 2008

At 18 he left home to walk the length of Europe; at 25, as an SOE agent, he kidnapped the German commander of Crete; now at 93, Patrick Leigh Fermor, arguably the greatest living travel writer, is publishing the nearest he may come to an autobiography – and finally learning to type. William Dalrymple meets him at home in Greece

‘You’ve got to bellow a bit,’ Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor said, inclining his face in my direction, and cupping his ear. ‘He’s become an economist? Well, thank God for that. I thought you said he’d become a Communist.’

He took a swig of retsina and returned to his lemon chicken.

‘I’m deaf,’ he continued. ‘That’s the awful truth. That’s why I’m leaning towards you in this rather eerie fashion. I do have a hearing aid, but when I go swimming I always forget about it until I’m two strokes out, and then it starts singing at me. I get out and suck it, and with luck all is well. But both of them have gone now, and that’s one reason why I am off to London next week. Glasses, too. Running out of those very quickly. Occasionally, the one that is lost is found, but their numbers slowly diminish…’

He trailed off. ‘The amount that can go wrong at this age – you’ve no idea. This year I’ve acquired something called tunnel vision. Very odd, and sometimes quite interesting. When I look at someone I can see four eyes, one of them huge and stuck to the side of the mouth. Everyone starts looking a bit like a Picasso painting.’

He paused and considered for a moment, as if confronted by the condition for the first time. ‘And, to be honest, my memory is not in very good shape either. Anything like a date or a proper name just takes wing, and quite often never comes back. Winston Churchill – couldn’t remember his name last week.

‘Even swimming is a bit of a trial now,’ he continued, ‘thanks to this bloody clock thing they’ve put in me – what d’they call it? A pacemaker. It doesn’t mind the swimming. But it doesn’t like the steps on the way down. Terrific nuisance.’

We were sitting eating supper in the moonlight in the arcaded L-shaped cloister that forms the core of Leigh Fermor’s beautiful house in Mani in southern Greece. Since the death of his beloved wife Joan in 2003, Leigh Fermor, known to everyone as Leigh Fermor, has lived here alone in his own Elysium with only an ever-growing clowder of darting, mewing, paw-licking cats for company. He is cooked for and looked after by his housekeeper, Elpida, the daughter of the inn-keeper who was his original landlord when he came to Mani for the first time in 1962.

It is the most perfect writer’s house imaginable, designed and partially built by Leigh Fermor himself in an old olive grove overlooking a secluded Mediterranean bay. It is easy to see why, despite growing visibly frailer, he would never want to leave. Buttressed by the old retaining walls of the olive terraces, the whitewashed rooms are cool and airy and lined with books; old copies of the Times Literary Supplement and the New York Review of Books lie scattered around on tables between Attic vases, Indian sculptures and bottles of local ouzo.

A study filled with reference books and old photographs lies across a shady courtyard. There are cicadas grinding in the cypresses, and a wonderful view of the peaks of the Taygetus falling down to the blue waters of the Aegean, which are so clear it is said that in some places you can still see the wrecks of Ottoman galleys lying on the seabed far below.

There is a warm smell of wild rosemary and cypress resin in the air; and from below comes the crash of the sea on the pebbles of the foreshore. Yet there is something unmistakably melancholy in the air: a great traveller even partially immobilised is as sad a sight as an artist with failing vision or a composer grown hard of hearing.

I had driven down from Athens that morning, through slopes of olives charred and blackened by last year’s forest fires. I arrived at Kardamyli late in the evening. Although the area is now almost metropolitan in feel compared to what it was when Leigh Fermor moved here in the 1960s (at that time he had to move the honey-coloured Taygetus stone for his house to its site by mule as there was no road) it still feels wonderfully remote and almost untouched by the modern world.

When Leigh Fermor first arrived in Mani in 1962 he was known principally as a dashing commando. At the age of 25, as a young agent of Special Operations Executive (SOE), he had kidnapped the German commander in Crete, General Kreipe, and returned home to a Distinguished Service Order and movie version of his exploits, Ill Met by Moonlight (1957) with Dirk Bogarde playing him as a handsome black-shirted guerrilla.

It was in this house that Leigh Fermor made the startling transformation – unique in his generation – from war hero to literary genius. To meet, Leigh Fermor may still have the speech patterns and formal manners of a British officer of a previous generation; but on the page he is a soaring prose virtuoso with hardly a single living equal.

It was here in the isolation and beauty of Kardamyli that Leigh Fermor developed his sublime prose style, and here that he wrote most of the books that have made him widely regarded as the world’s greatest travel writer, as well as arguably our finest living prose-poet. While his densely literary and cadent prose style is beyond imitation, his books have become sacred texts for several generations of British writers of non-fiction, including Bruce Chatwin, Colin Thubron, Philip Marsden, Nicholas Crane and Rory Stewart, all of whom have been inspired by the persona he created of the bookish wanderer: the footloose scholar in the wilds, scrambling through remote mountains, a knapsack full of books on his shoulder.

Germany carved amongst her neighbours

What is this cartographic madness? Hanover part of the Netherlands? Kassel ruled by France? Nuremburg part of a Bohemia that reaches to the Frankfurt suburbs? Hamburg in Denmark? Regensburg on the Austro-Czech border? I came across the company Kalimedia in an article from Die Zeit a month or two ago and discovered their map of a Europe without a Germany. Believe it or not, there were plans of one sort or another to achieve similar results at the end of the Second World War. The major plan for the dissection of Germany was merely a creation of Nazi propaganda, and while the vaguely similar Morgenthau Plan did exist, it was soon shelved once its impracticality became obvious.

The Bakker-Schut Plan, meanwhile, was a Dutch proposal for the annexation of several German towns, and perhaps even a number of German cities. German natives would be expelled, except for those who spoke the Low Franconian dialect, who would be forcibly dutchified. They even came up with a list of new Dutch names for German cities: c.f. the post at Strange Maps on “Eastland, Our Land: Dutch Dreams of Expansion at Germany’s Expense”.

A Miracle from Blessed Charles

Vatican to Review Case of Inexplicable Healing of Florida Woman

The seemingly inexplicable healing of a Baptist woman from Florida may provide the miracle necessary for the canonization of Emperor Charles of Austria. The woman, in her mid-50s, suffered from breast cancer and was bedridden after the cancer had spread to her liver and bones. Despite treatment and hospitalization, doctors diagnosed her case as terminal. But after intercessory prayers to the Emperor Charles, the woman (who wishes to maintain her privacy and remain unnamed) was completely healed.

The story begins when Joseph and Paula Melançon, a married couple from Baton Rouge, Louisiana and friends of the healed woman, travelled to Austria, where they met Archduke Karl Peter, son of Archduke Rudolf, and grandson of the holy Emperor Charles. The Archduke invited the couple to his grandfather’s beatification in Rome in 2004. Mrs. Melançon gave the novena to Blessed Charles to her sister-in-law, Vanessa Lynn O’Neill of Atlanta.

“I knew that when I got that novena — I knew that my mother’s best friend was sick — I just knew at that moment that it was something I was going to do,” Mrs. O’Neill told the Florida Catholic in an interview. “And that is how I got started, I just prayed the novena.”

The woman’s recovery was investigated by an official church tribunal consisting of Father Fernando Gil (judicial vicar of the Diocese of Orlando), Father Gregory Parkes (chancellor of canonical affairs of the Diocese), Father Larry Lossing, diocesan notary Delma Santiago, as well as an unnamed medical doctor. The tribunal examined the evidence at hand and invited the participation of medical experts, who could find no earthly explanation for the woman’s recovery.

“Other alleged miracles attributed to the intercession of Blessed Karl I are currently being investigated in different places in the world,” Fr. Gil said.

The sixteen-month investigation has now concluded, and the conclusions have been signed by the participants, sealed, and placed in special boxes which are then themselves tied, sealed with wax, and sent to the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints in Rome via diplomatic pouch. The Congregation will examine the case further and then present its findings to Pope Benedict XVI, who will decided if a miracle has taken place. If the Pope is convinced by the evidence, then the Emperor’s canonization can proceed.

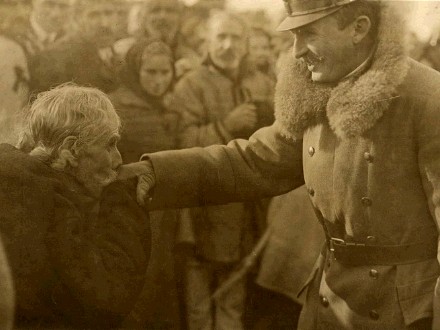

The future emperor, 1889 |

Blessed Charles’s reign as Emperor of Austria and Apostolic King of Hungary began in November 1916 during the First World War. The Emperor realized the heavy toll the Christian countries were suffering and almost immediately began to make peace manouevers. The insane obstinacy of both his German allies and the enemy alliance of France, Great Britain, and the United States, however, meant that Charles’s multiple attempts to negotiate a mutually-acceptable end to the war were not even considered.

After the war, President Woodrow Wilson insisted on dismantling the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Emperor was forced into exile, first in Switzerland and finally, after two attempts to regain his Hungarian throne, on the Portuguese island of Madeira. Charles had always been particularly devout, and his devotion to God only increased when he caught a severe case of pneumonia on Madeira. He died from the illness in April 1922.

The English writer Herbert Vivian wrote that Charles was “a great leader, a prince of peace, who wanted to save the world from a year of war; a statesman with ideas to save his people from the complicated problems of his empire; a king who loved his people, a fearless man, a noble soul, distinguished, a saint from whose grave blessings come.”

Even Anatole France, the radical French intellectual and novelist, wrote “Emperor Karl is the only decent man to come out of the war in a leadership position, yet he was a saint and no one listened to him. He sincerely wanted peace, and therefore was despised by the whole world. It was a wonderful chance that was lost.”

Recent history has come to fulfil the expectations of Pope St. Pius X, who received Charles when the Austrian was a young archduke and not in direct line to succeed to the throne, saying “I bless Archduke Charles, who will be the future Emperor of Austria and will help lead his countries and peoples to great honor and many blessings–but this will not become obvious until after his death.”

Mourning in Vienna

The Blessed Emperor Charles at the funeral of the late Emperor Franz Joseph, the saint’s great uncle, in November 1916. Between the Blessed Charles and his Empress, Zita of Bourbon-Parma, is Crown Prince Otto. Otto lives today, and is the head of the Hapsburg family.

Grant us the grace, with his intercession, to follow his example and serve the true cause of peace, which we find in the faithful fulfillment of Your holy will. We ask this through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with You and the Holy Spirit, one God, forever and ever.

Amen.

Category: Monarchy | Previously: Our Holy Emperor

Archduke Carl Ludwig, 1918-2007

Son of Blessed Charles, U.S. Army Veteran, Fought at Normandy

A READER WAS kind enough to bring to my attention the recent death of His Imperial & Royal Highness, Archduke Carl Ludwig Maria Franz Joseph Michael Gabriel Antonius Robert Stephan Pius Gregor Ignatius Markus d’Aviano of Austria, one of the sons of Blessed Charles, the last (up to this point) Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary, King of Bohemia, etc. Carl Ludwig’s birth in 1918 was hailed with a 101-gun salute from the imperial field artillery, but the Habsburgs were soon overthrown by a republican element in Vienna and forced into exile. The Archduke studied at the University of Louvain until the outbreak of the Second World War, when the Habsburgs fled to the safety of Quebec.

There, the family were so poor they sometimes had to survive off a soup the Empress Zita cheerfully prepared from dandelions picked in the park. Carl Ludwig, however, was able to complete his studies at the Université Laval, the oldest university in Canada, before being allowed to join the United States Army in 1943. On June 6, 1944, he took part in the D-Day landings in Normandy, and later became aide-de-camp to the Comte de Hauteclocque, a general in the Free French Forces (later known as Maréchal Leclerc), and served with the Algerian spahis. He was discharged from the U.S. Army with the rank of Major in 1947, and in 1950 married Princess Yolande de Ligne.

Our Holy Emperor

OCTOBER 21 IS the feast of Blessed Charles of Austria, the saintly emperor of that sacred realm whose life stands as an example of the price of sanctity. Charles worked tirelessly for peace both between the peoples of his own numerous realms and between all the nations, seeking to bring to an end the ceaseless and suicidal slaughter of the Great War, in the midst of which he had ascended to the throne of his fathers. A defender of social order, Charles reminds us of our many responsibilities to each other, even though the spirit of our current age would have us clamor only for our supposed rights. In the face of repeated betrayal and intense pressure, he refused to abdicate and so abandon his peoples to their fates, which were terrible indeed. That terrible cross he bore, the crown, was in fact a penitential grace, the sufferings he bore for the benefit of his – and indeed all – people. His reward was not in this world.

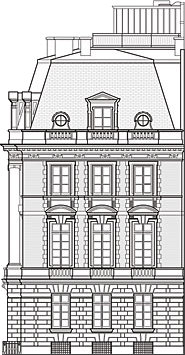

The Neue Galerie

THE RECENT PURCHASE for the Neue Galerie of Gustav Klimt’s 1907 ‘Adele Bloch-Bauer I’ (above), alledgedly for a record-breaking price of $135,000,000, gives me the perfect opportunity to write a post on the eponymously recent addition to New York’s coterie of art museums. Since its 2001 opening, the Neue Galerie has resided in the handsome 1914 beaux-arts mansion on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 86th Street, designed by Carrère and Hastings (of New York Public Library fame) for industrialist William Starr Miller and later inhabited by Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt III. In the time since the construction of No. 1048, the rest of Fifth Avenue has undergone a lamentable transformation from a boulevard of beautiful townhouses and mansions to an avenue predominantly consisting of apartment buildings. While one appreciates the inoffensive design of the pre-war buildings on Fifth, there remain a number of thoroughly opprobrious modern interlopers which offend the graceful avenue. One can’t help but pine for Fifth Avenue before the mansions came down, but we can at least give thanks for holdouts like the Neue Galerie. (more…)

THE RECENT PURCHASE for the Neue Galerie of Gustav Klimt’s 1907 ‘Adele Bloch-Bauer I’ (above), alledgedly for a record-breaking price of $135,000,000, gives me the perfect opportunity to write a post on the eponymously recent addition to New York’s coterie of art museums. Since its 2001 opening, the Neue Galerie has resided in the handsome 1914 beaux-arts mansion on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 86th Street, designed by Carrère and Hastings (of New York Public Library fame) for industrialist William Starr Miller and later inhabited by Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt III. In the time since the construction of No. 1048, the rest of Fifth Avenue has undergone a lamentable transformation from a boulevard of beautiful townhouses and mansions to an avenue predominantly consisting of apartment buildings. While one appreciates the inoffensive design of the pre-war buildings on Fifth, there remain a number of thoroughly opprobrious modern interlopers which offend the graceful avenue. One can’t help but pine for Fifth Avenue before the mansions came down, but we can at least give thanks for holdouts like the Neue Galerie. (more…)

The Remarkable Hapsburgs

Last night, Fr. Emerson popped up from Edinburgh and gave a talk on the Hapsburg dynasty. It was tremendously interesting. I learned so much I hadn’t known before and it opened up a terrific number of avenues of information down which I have only begun to stroll.

I had no idea how remarkable a man Franz Ferdinand was. All they teach you in America is “This is the guy who got shot” instead of “This man would have been the savior of all that is good and holy in Europe.”

I have seen and read a lot of what Europe is today; Fr. Emerson gave us a glimpse of what Europe was yesterday, before the utter destruction of the social order of the continent by that moment in Sarajevo and everything that came after it. Knowing what Europe was, how depressing to see it now!

It also filled me with some optimism, oddly enough. I used to be partly in the school of thought that’s convinced that Europe is lost. If this is how Europe was, surely it could be again? Perhaps, perhaps not. (more…)

Charles I, Emperor, King, Saint!

Almighty God, Lord of Lords and King of Kings, in Your infinite fatherly love you are keeping watch over the fate of men and nations. You called Your servant, Emperor and King Charles of the House of Austria, to serve as a father to his peoples in difficult times and to promote peace with all his strength. By sacrificing his life, he sealed his willingness to fulfill Your holy will.

Grant us the grace, with his intercession, to follow his example and serve the true cause of peace, which we find in the faithful fulfillment of Your holy will. We ask this through him, Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with You and the Holy Spirit, one God, forever and ever. Amen.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories