Tradition

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Mendicant Architecture in Mediaeval Oxford

An interesting video from two American academics on the subject of Mendicant architecture in mediaeval Oxford, with some three-dimensional theoretical reconstructions of the Dominican and Franciscan houses in the city.

Both orders returned to Oxford in the twentieth century. The Capuchins refounded Greyfriars in 1910 and it was recognised as a permanent private hall (PPH) of the University in 1957. Its end as an academic institution was announced sadly on its fiftieth anniversary in 2007, but Greyfriars continues as a Capuchin friary.

Blackfriars under the Dominicans is still going strong, exercising a triple function as a priory of the Order of Preachers, a house of studies for the English province of the Order, and a PPH of the University of Oxford.

Judging Dress

After some absence, The Sybarite has returned and, in A Love Supreme, he weighs in on the very important matter of judicial dress.

I am, it will surprise no-one to know, deeply traditionalist in such matters. I can see the argument for discarding formal court attire in cases involving children, who might be intimidated by wigs and gowns (as a child, I myself would have been as happy as a pig in the proverbial). But I feel strongly that “work clothes”, whether worn by judges, barristers, politicians or clerks in Parliament, are important. They are part of the persona. You are not Alf Bloggs, you are Mr Justice Bloggs and you are performing an important public role. When you put on the clothes, you put on the role. Of course, I am fighting a rearguard action here – I know that the tide of public opinion is against me. If the clerks at the Table in the House of Commons still wear wigs in ten years’ time, I will be (pleasantly) surprised.

As the Supreme Court was set up in the modish New Labour years, it was inevitable they would dispense with much of the ceremonial. The Justices wear lounge suits to hear cases, though I think in some cases the barristers still wear wigs and gowns. The one concession has been the black-and-gold gowns which the Justices don for special occasions. These are fine so far as they go – and, as observed above, Lady Hale of Richmond likes to accessorise hers with a Tudor bonnet – though they bear on the back the badge of the Supreme Court, which I think looks a bit tacky and smacks of footballers’ names and numbers on the back of their shirts. But they also look a bit odd worn over lounge suits or equivalent. At least successive Lord Chancellors since the role was recast by Blair have retained formal court dress for high and holy days. Mind you, the current occupant, Miss Truss, does look a bit like the principal boy in a pantomime when she wears knee breeches. But fair play to her for continuing to wear the traditional robes, even if the full-bottomed wig seems now to have gone the way of the dodo.

It could be worse. The Supreme Court Justices could wear ghastly zip-up gowns like their American counterparts – you just know they’re made of nylon – over their suits, though I have some time for Justice Ginsberg for adding a lace jabot to tidy up her garb a little. But ceremonial is something that Britain does so well. The Supreme Court could have looked so much better with Justices in gowns and traditional judicial clothing. A wig here and there wouldn’t go amiss.

I couldn’t agree more. Especially on the matter of the badge of the Supreme Court on the back on the gowns, which is simply naff. (See image below.)

But why do the justices of the Supreme Court have (what I think of as) chancellorial gowns anyhow? What is the origin of this style of black-and-gold gown? Did it start with the Lord Chancellor and spread to the Speaker or vice versa? Or have some species of judge always worn chancellorial gowns? The chancellors of universities have likewise adopted it, though its precise form varies from institution to institution, as one might expect in matters of academic dress.

Incidentally, I was speaking with Bob Geldof the other day about Senator W. B. Yeats, about whom Mr Geldof has done a documentary. As we were discussing Yeats’ contribution to the Irish Senate, Mr Geldof mentioned that Yeats had been in discussions with Hugh Kennedy, the Chief Justice of the Irish Free State, about introducing new designs for Irish judicial dress. The results, according to just about everyone, left much to be desired and so the British tradition carried on for the most part. As is so often the case, doing nothing is the least bad option.

The Dutch in Rhodesia

…and why they stayed there.

Journalist Marnix de Bruyne has shed new light on the post-war wave of Dutch immigration to Rhodesia with his new book, We moeten gaan. Nederlandse boeren in Zimbabwe (‘We Must Go: Dutch Farmers in Zimbabwe’).

Journalist Marnix de Bruyne has shed new light on the post-war wave of Dutch immigration to Rhodesia with his new book, We moeten gaan. Nederlandse boeren in Zimbabwe (‘We Must Go: Dutch Farmers in Zimbabwe’).

Why did so many people emigrate from the Netherlands in the fifties? Why did hundreds of them choose to settle in what was then called Rhodesia, today’s Zimbabwe? And why did so many of them stay after 1965, when the country was led by a white-minority regime, faced an international boycott and was engulfed in a bloody guerrilla war?

De Bruyne attempted to answer these questions through a recent seminar at Leiden University’s African Studies Centre. The university has rather handily made a recording of the seminar available online.

Daar’s ook ’n interview (in Nederlands) met Mnr de Bruyne in Mare, die koerant van die Universiteit Leiden.

(Dave: hierdie post is vir jy!)

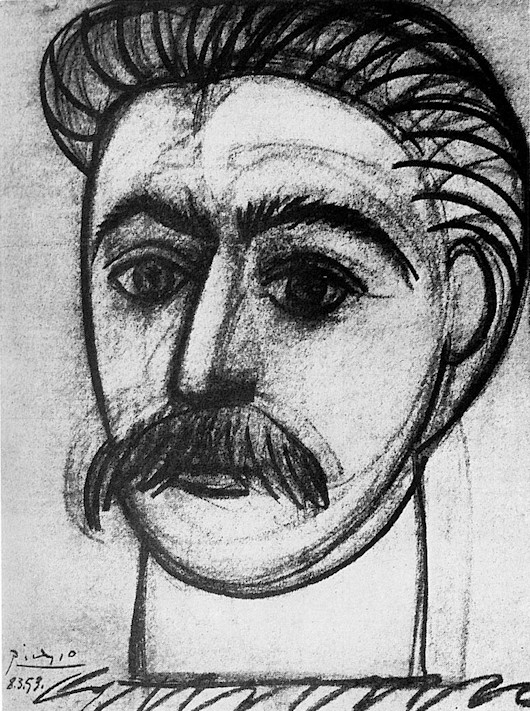

The Death of God the Father

When Stalin’s death was announced on Friday, 7 March 1953, Aragon called in Pierre Daix and rattled off a shopping list of features to honour Stalin in a special issue of Les Lettres françaises. […] Since Picasso had always refused to do a portrait of Stalin from a photograph, Daix sent a telegram to him at Vallauris saying, ‘Do whatever you want,’ and signed it ‘Aragon’.

Picasso’s drawing of Stalin, which depicted him as a curiously open-eyed young man, arrived at the very moment Les Lettres françaises went to press. Daix took the picture to Aragon. He admired it and said that the party would appreciate the gesture. While it was being set into the front page, office boys and typists crowded round the picture. Everyone thought it ‘worthy of Stalin’.

Daix was overjoyed to be the one who had commissioned Picasso’s first portrait of the Soviet leader and rushed it down to the printers. But a few hours later, when the edition had been run off, the mood in the building had completely changed to one of fear. Journalists from L’Humanité, passing by, spotted the drawing and cried out that it was unthinkable that any Communist publication should consider such a representation of ‘le Grand Staline’.

Pierre Daix promptly rang Aragon at his apartment; Elsa Triolet answered. She told him angrily that he was mad to have even thought of asking Picasso for such a drawing.

‘But really, Elsa,’ Daix broke in, ‘Stalin isn’t God the Father!’

‘Yes, he is, Pierre. Nobody’s going to reflect much about what this drawing of Picasso signifies. He hasn’t even deformed Stalin’s face. He’s even respected it. But he has dared to touch it. He has actually dared, Pierre, don’t you understand?’ […]

Antony Beevor & Artemis Cooper (1994, London)

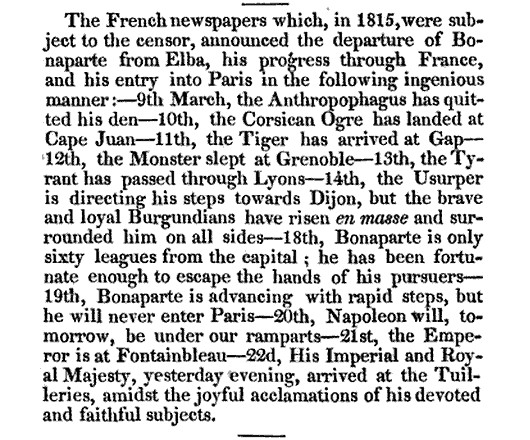

The Anthropophagus Has Quitted His Den

The Museum of Foreign Literature Science and Arts was a Philadelphia periodical edited by the prodiguously talented and unjustly neglected Eliakim Littell.

In January 1831 his review published this little snippet of headlines claimed to have been clipped from French newspapers:

The French newspapers which, in 1815, were subject to the censor, announced the departure of Bonaparte from Elba, his progress through France, and his entry into Paris in the following ingenious manner:

March 9 THE ANTHROPOPHAGUS HAS QUITTED HIS DEN

March 10

THE CORSICAN OGRE HAS LANDED AT CAPE JUAN

March 11

THE TIGER HAS ARRIVED AT GAP

March 12

THE MONSTER SLEPT AT GRENOBLE

March 13

THE TYRANT HAS PASSED THOUGH LYONS

March 14

THE USURPER IS DIRECTING HIS STEPS TOWARDS DIJON

but the brave and loyal Burgundians have risen en masse

and surrounded him on all sidesMarch 18

BONAPARTE IS ONLY SIXTY LEAGUES FROM THE CAPITAL

He has been fortunate enough to escape the hands of his pursuersMarch 19

BONAPARTE IS ADVANCING WITH RAPID STEPS

But he will never enter ParisMarch 20

NAPOLEON WILL, TOMORROW, BE UNDER OUR RAMPARTS

March 21

THE EMPEROR IS AT FONTAINEBLEAU

March 22

HIS IMPERIAL & ROYAL MAJESTY, yesterday evening, arrived at the Tuileries, amidst the joyful acclamation of his devoted and faithful subjects.

In the Old Dutch East Indies

Little Holland’s rule over this vast land – today the world’s largest Muslim country by population – never loomed large in the European imagination (the Netherlands excepted) and thus has been too easily forgotten. Peter van Dongen’s Rampokan series of graphic novels (in Herge’s ligne-claire style) is the most prominent recent attempt to shine some light on the Dutch East Indies and it has obtained a bit of a cult following.

The colonial architecture went through the usual transformations, from awkward hybrids of the motherland and the vernacular to a cool and crisp classical elegance of the later imperial buildings. Henri Maclaine Pont’s work at Bandung is probably the most successful Dutch take on local building traditions, and in some ways Geoffrey Bawa is his spiritual offspring.

The ministries of Indonesia’s government still convene in elegant Dutch colonial buildings, though the names have all changed. The Daendels Palace is now the Finance Ministry, Buitenzorg is now Bogor, and the old Koningsplein is now the Medan Merdeka or Freedom Square. (more…)

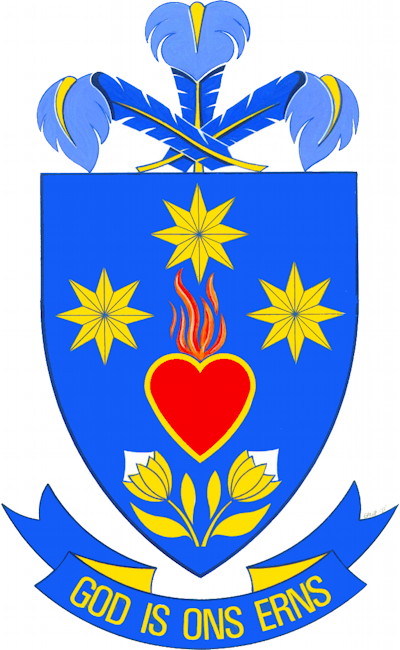

Arms of the Oudtshoorn Oratory

An explanation of the arms of the Afrikaans-speaking Oratory of St Philip Neri in Oudtshoorn, South Africa (edited from their own information).

Past and Future Meet in Peru’s Navy

Lima’s Latest Warship Boasts Four Masts and Full Rigging

Today the Peruvian Navy’s newest ship, the BAP Unión, returns to its home port of Callao after an 8,900-mile tour at sea that took in eight countries over 98 days. But though commissioned earlier this year by then-President Ollanta Humala, the Unión isn’t some grey-painted stealth frigate but a four-masted, steel-hulled, full-rigged barque. Named after a corvette that saw action in the War of the Pacific, the Unión was laid down at Callao’s SIMA shipworks in 2010, launched in 2014, and was commissioned this past January as the primary training vessel of the Peruvian fleet.

The unimaginative might be surprised that such old-school ships are being used to train modern sailors, but the Unión’s Commander Roberto Vargas is unambiguous.

“On modern warships, working with computers and satellites all the time, we forget that we have to learn the essentials of sailing,” Commander Vargas told the Miami Herald.

“On a ship like the Unión, these cadets learn leadership, they learn cooperation, they learn group spirit. It’s impossible to work alone with these big sails — you have to work with other people. And most of the basics, like navigation and oceanography, are the same.”

Many other Latin American countries use tall ships as naval training vessels. Argentina’s ARA Libertad was the subject of an attempted seizure by foreign vulture funds seeking payments on debts defaulted upon in 2002.

While most date from the 1960s (Colombia’s Gloria), ’70s (Ecuador’s Guayas; Venezuela’s Simón Bolívar), or ’80s (Mexico’s Cuauhtémoc), Chile’s Esemeralda was launched in 1946. The grande dame of them all is Uruguay’s schooner the Capitán Miranda, launched in 1930 but docked since 2013 awaiting decisions on upgrades.

One analyst notes that even two-hundred years later the old imperial connections are still thriving in the strong Spanish influence on many of these ships:

The Peruvian state-controlled shipyard SIMA (Servicios Industriales de la Marina) constructed the Union in its shipyard in the port of Callao, but the Spanish company CYPSA Ingenieros Navales cooperated in the vessel’s structural design.

As for other ships, many were constructed by Spanish companies. For example Colombia’s Gloria, Ecuador’s Guayas, Mexico’s Cuauhtemoc, and Venezuelan’s Simon Bolivar were all manufactured by Astilleros Celaya S.A., while Chile’s Esmeralda was obtained from the Spanish government which constructed it at the Echevarrieta y Larrinaga shipyard in Cadiz.

One exception to the rule is Brazil’s Cisne Branco, which was constructed by the Dutch company Damen Shipyard.

Given the return to tradition in Peru’s army that we had previously reported on, it’s a pleasure to see this continuing in the country’s navy. Peru continues to show the world that another future is possible.

Entering the old harbour of Havana, Cuba.

Above and below, decked out for commissioning in Callao.

President Humala at the commissioning ceremony.

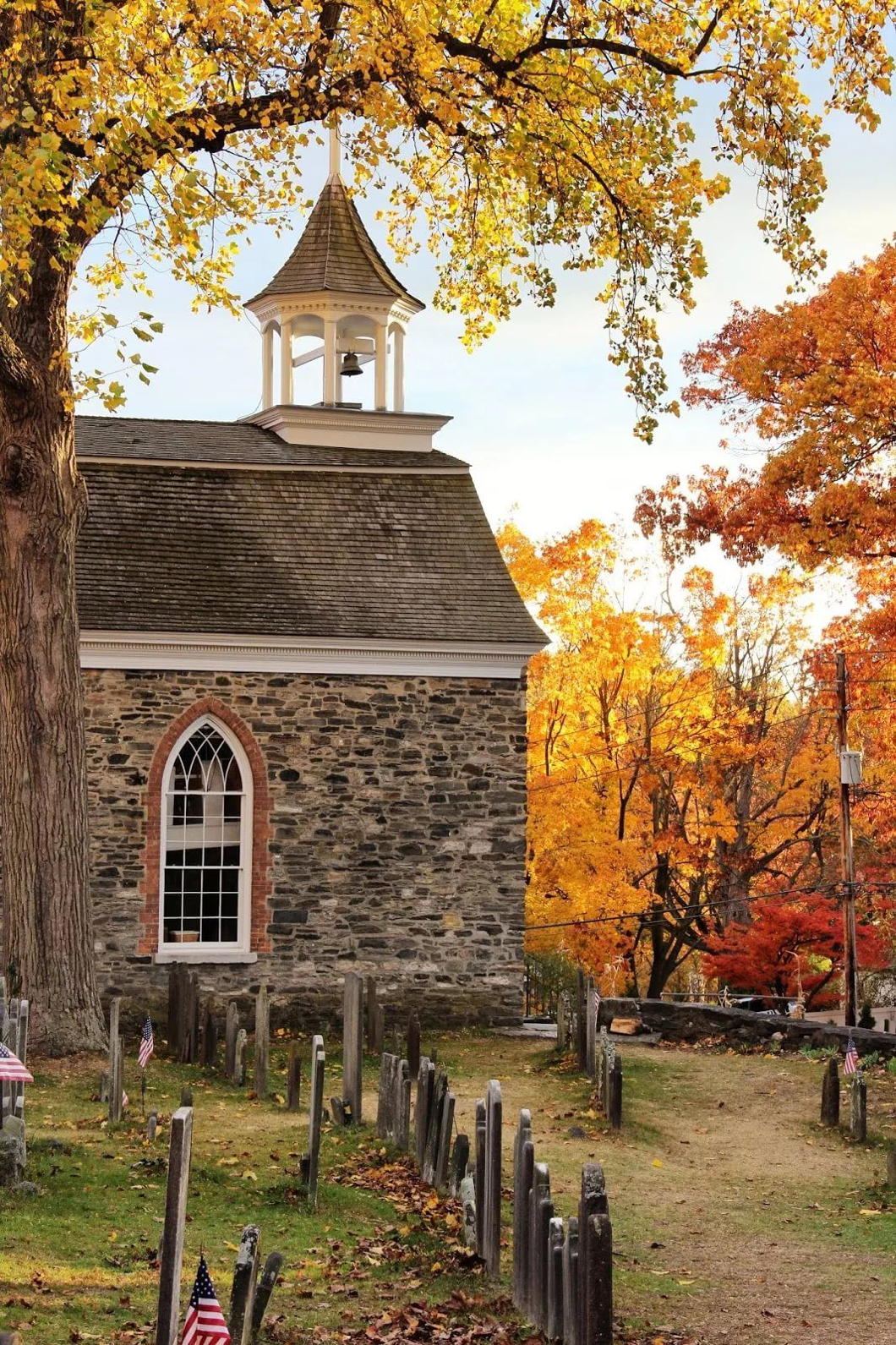

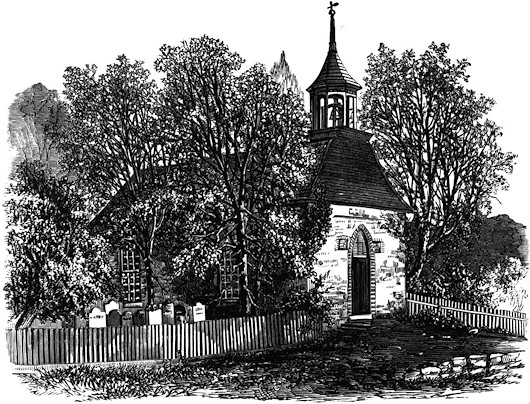

The Old Dutch Church of Sleepy Hollow

If there is any season which is plus New-Yorkaise que les autres then it must be autumn, and around the time of Hallowe’en in particular.

Thanks to the fertile imagination of Washington Irving, buried in the cemetery of the Old Dutch Church in Sleepy Hollow, the Hudson Valley is the spiritual home of this ancient Celtic feast now implanted in the New World.

The other day I dusted off the huge single-volume complete works of Irving – almost the size of an old Statenvertaling – and re-read his most famous tale, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”.

Irving describes the position of the Old Dutch Church:

The sequestered situation of this church seems always to have made it a favorite haunt of troubled spirits. It stands on a knoll surrounded by locust trees and lofty elms, from among which its decent whitewashed walls shine modestly forth, like Christian purity beaming through the shades of retirement. A gentle slope descends from it to a silver sheet of water bordered by high trees, between which peeps may be caught at the blue hills of the Hudson. To look upon its grass-grown yard, where the sunbeams seem to sleep so quietly, one would think that there at least the dead might rest in peace.

On one side of the church extends a wide woody dell, along, which raves a large brook among broken rocks and trunks of fallen trees. Over a deep black part of the stream, not far from the church, was formerly thrown a wooden bridge; the road that led to it and the bridge itself were thickly shaded by overhanging trees, which cast a gloom about it even in the daytime, but occasioned a fearful darkness at night. Such was one of the favorite haunts of the Headless Horseman, and the place where he was most frequently encountered.

The tale of the Headless Horseman is now, partly thanks to various popular reinterpretations of it, well known even outside the Hudson Valley. I remember as a wee lad growing up in that part of the world our Scout uniforms had a badge bearing the image of the “Galloping Hessian”.

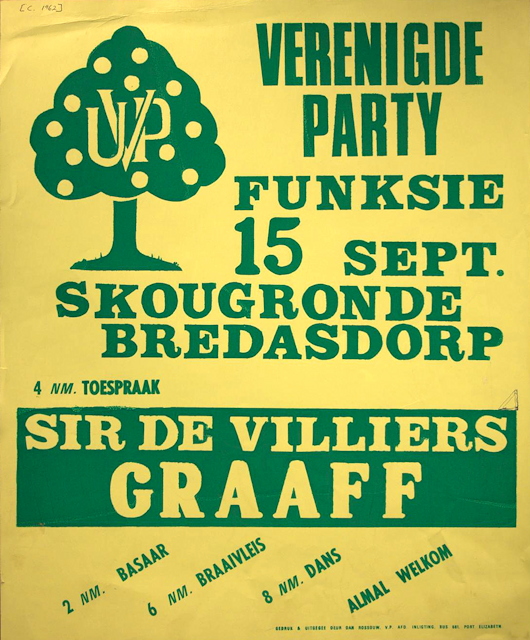

Party in the Overberg

Alongside a bazaar, a braai, and dancing, a speech by Sir De Villiers Graaff is the selling point of this poster advertising a United Party (Verenigde Party) get-together in the beautiful Overberg region of the Cape.

“Sir Div” was the inheritor of one of only twelve South African baronetcies and led his party from 1956 until 1977 when it merged with the Democratic Party of verligte ex-Nationalists to form a new entity.

The broadly centrist party had lost power to the republican Nats (creators of apartheid) in 1948, and suffered splits that led to the creation of the Liberal Party and the United Federal Party in 1953, the National Conservative Party in 1954, and the Progressive Party in 1959.

The party’s emblem was a happy little citrus tree.

Botswana and Hereditary Power

To any observer it must be obvious that hereditary power of some kind is natural and most of the time inescapable. It’s not that you need to be born into power to wield it, but experience shows it doesn’t hurt. Since I was born, there has been just one American presidential election (2012) in which a member of either the Bush or Clinton families was not either the official candidate of their respective party or a significant contender for that role.

In Canada, the current prime minister has sailed into office solely on a combination of good looks and being the son of a previous prime minister. In Ireland there are no fewer than forty-one families who have had three or more members elected to the Oireachtas (or to the Commons before it). The relatives and descendants of Timothy Sullivan managed to elect thirteen members between 1874 and 2016 as MPs, TDs, senators, or MEPs. Sullivan’s son and great-grandson both served as Chief Justice of Ireland to boot.

Sir Seretse Khama

Botswana — the most succesful state in Africa by many gauges — today celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of its assuming the mantle of sovereignty after eighty-one years as a British protectorate. Given that the United States, Canada, and Ireland are generally viewed as succesful countries, the hereditary aspect of power might help explain the comparitive success of Botswana, a multiparty state with free and fair elections, relative to its neighbours. The fourth and current president is Ian Khama, formerly a lieutenant general in the Botswana Defence Force. President Khama is the son of Sir Seretse Khama, the Balliol man who led his country and its people to independence fifty years ago and served as Botswana’s first president. Sir Seretse in turn is the grandson of King Khama III, last kgosi of Bechuanaland before the protectorate and leader of the Bamangwato tribe.

When Sir Seretse Khama became leader of Botswana it was the third poorest country in Africa — now it is the sixth richest on the continent in terms of GDP per capita. In a continent not known for good government Botswana, though not without its problems, is an oasis of stability and order.

At today’s celebrations for the fiftieth year of independence, President Khama wasn’t taking any credit for his country’s success: “Where we may have failed we take the blame. Where we succeeded we thank God.”

Oliver VII

by Antal Szerb, trans. by Len Rix

Pushkin Press (2013), £12, 208 pages

Hungarian by nationality, Catholic by faith, Jewish by blood — Antal Szerb was capable of touching the boundaries of intense seriousness bordering on the mystical (as in Journey by Moonlight) or magical (The Pendragon Legend) even though he is probably better known as paragon and only member of the interwar neo-frivolist school of literature.

Here he is at his frivolous best with a novel about the monarch of a Ruritanian kingdom in crisis who abdicates and escapes to Venice incognito, where he falls in with a crowd of confidence tricksters who ultimately, unaware of the ex-king’s true identity, force him to impersonate himself.

In Oliver VII, romance, intrigue, and the perpetual allure of the genteel portion of the criminal class all combine in an enjoyable farce.

The Red Mass in Edinburgh

The opening of Scotland’s judicial year was marked this past Sunday by the Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh offering the customary Red Mass in St Mary’s Cathedral.

This year Archbishop Leo Cushley was joined by Lord Drummond Young and his fellow Senators of the College of Justice, Lord Uist, Lord Doherty, Lord Matthews, and Lady Carmichael.

Gordon Jackson QC, the Dean of the Faculty of Advocates, and Austin Lafferty of the Law Society of Scotland joined many sheriffs, QCs, advocates, solicitors, trainee solictors, paralegals, and law students.

“These men and women serve the nation in a high office and come here to ask the Lord’s blessing upon this year’s work that they carry out on our behalf,” Archbishop Cushley noted in his homily.

“Know that we appreciate the difficult and complex tasks that you have and the duties that you perform – which are very onerous – on behalf of us all and that you be assured of our prayers and our support for all that you do to apply the law of the land with virtue and with justice and with mercy.”

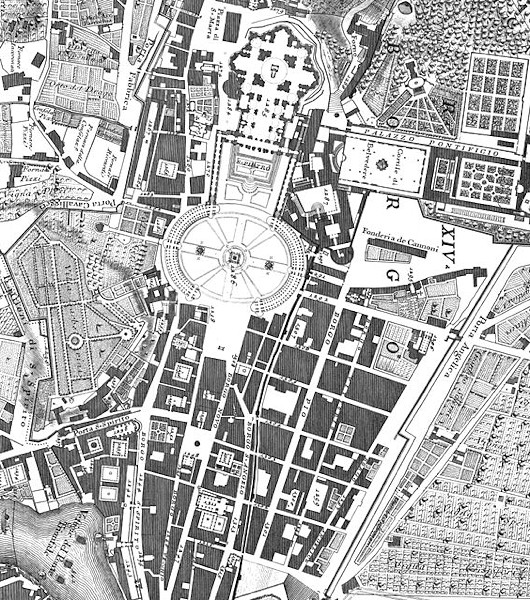

The Spina di Borgo

The Baroque is a style of joy. It is often hailed (or derided) as the most Catholic of styles and in some sense this is true. The festivity and physicality of the Baroque reflect the God that Catholics worship — “the Love that moves the Sun and other stars” as Dante put it — but a Love made incarnate, made man, in a very real and tangible world.

The Baroque is also the style of the surprise: the corner turned to an unexpected vista or the jet of water sprinkling a king’s unsuspecting courtier.

One of the most superb examples of this was the great basilica church of Saint Peter in Rome where prince, pilgrim, and pauper alike moved in a dark warren of palaces, hovels, churches, and alleyways, perhaps catching an occasional glimpse of the great dome looming as they closed in on San Pietro, finally to emerge from the shadow into the great light of the piazza.

That warren of buildings was the Spina di Borgo (“Spine of the Borgo”) but this experience is now sadly lost to us since the 1930s when the Kingdom of Italy’s fascist premier Benito Mussolini decided to raze the neighbourhood. Instead we now have the long boulevard called the Via della Conciliazione, named in commemoration of the Lateran Treaty establishing formal relations between the Holy See and the Italian state.

While Il Duce ostentatiously took credit for this urban crime by symbolically swinging the pickaxe beginning demolition, the concept, though flawed, was in fact an old one. Leon Battista Alberti submitted proposals during the reign of Pope Nicholas V (mid fifteenth century), and numerous other architects — Carlo Fontana, Giovanni Battista Nolli, Cosimo Morelli — drew up similar plans. The Piazza San Pietro only took its now instantly recognisable form in the 1650s when the curved flanking collonades enclosed the space like great welcoming arms superbly framing the basilica’s façade.

Mussolini turned to Marcello Piacentini — an accomplished if sometimes uneven architect — assisted by Attilio Spaccarelli. Piacentini favoured closing off the view from the avenue with a closed collonade, echoing Bernini’s own plans for the piazza, but was overruled.

The razing of the Spina presented a problem in that the undemolished buildings left flanking the Via della Conciliazione were now mostly at odd angles to the new boulevard. Piacentini attempted to solve this by flanking the road with two rows of obelisks that doubled as streetlamps providing a line directing the viewer towards the great basilica beyond, otherwise unimpeded by any visual interruption.

Overall the construction of the Via leaves a rather boring and clinical feeling. The charm and chaos of the Spina has been replaced by a clean and dull boulevard, useful for little more than traffic efficiency and crowd control. The loss of the Spina di Borgo is mourned.

The Flag of the Arab Revolt

An English Catholic contribution to Pan-Arabist vexillology

Though often overshadowed by the more theatrical T.E. Lawrence, Sir Mark Sykes (7th baronet) was still by all accounts a remarkable man. Educated by Jesuits in England, Monaco, and Belgium, young Sykes had instilled in him a cosmopolitan sense of adventure by travelling with his mother across the Middle East, Mesopotamia, India, and Asia throughout his childhood.

It was during his travels in the provinces of the Ottoman empire that Sykes’s lifelong fascination with Islam began. By the time it was appropriate to go to university he found the atmosphere and formality of Cambridge stifling and left without taking a degree, but not without gaining a reputation for good humour with a special talent for mimicry.

At 25 Sykes wrote his first book, Dur-ul-Islam, which Kipling found so fascinating he couldn’t put it down until forced to by the necessity of sleep.

At 25 Sykes wrote his first book, Dur-ul-Islam, which Kipling found so fascinating he couldn’t put it down until forced to by the necessity of sleep.

After forays in the civil and diplomatic services, Sykes was elected to Parliament as the Unionist candidate in Kingston upon Hull. A romantic tory at heart, he disliked being labelled as conservative. “It is impossible to be a Conservative,” Sykes argued, “when there is nothing left to Conserve.”

When the Great War broke out in August 1914, Sykes recruited a batallion of men from his Yorkshire estates alone, but his unique insight into the Ottoman empire was put to good use in military intelligence. In May 1916 he was sent to negotiate the Anglo-Franco-Russian carving-up of Ottoman Asia with Charles Georges-Picot of the Quai d’Orsay.

The question of what the Turks’ Arab subjects themselves wanted only became a question the following month with the beginning of the Great Arab Revolt. This huge undertaking to wrest the Arab peoples from centuries of Turkish rule found a leader in the Sharif and Emir of Mecca, Hussein bin Ali of the Hashemite dynasty, but the uprising needed a symbol to rally round, and Sykes was the man for the job.

The flag of the Arab Revolt that Sir Mark Sykes designed was to be one of the most influential flags in the history of vexillology, launching the four pan-Arab colours into the world of flag design. Black represented the Abbasid dynasty, green for the Fatimids, and white for the Ummayad, all of which was united by a triangle of red for the Hashemites who hoped to rule Arabia.

Twelve modern states today employ designs descended from the flag Sykes designed. Among them is Jordan, now the only land ruled by the Hashemites – the Sauds kicked them out of Hejaz while the brutal slaughter of the 1958 coup deprived them of the Iraqi throne.

Jordan’s Red Sea port of Aqaba was made famous by its capture during the Great Arab Revolt – retold in David Lean’s 1962 film ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ – and it is there today that Sykes’s flag flies from one of the tallest flagpoles in the world.

An Old Name Returns to Banking

or: What Daniel O’Connell has to do with the 2008 Banking Crisis

Daniel O’Connell was a remarkable man by any stretch of the imagination, and is most often recalled for his part in bringing about the Relief Act of 1829 which emancipated the Catholics of Great Britain and Ireland from an officially oppressed legal status. Among his many achievements, however, was in London in 1825 founding the National Bank of Ireland.

As the RBS Group’s website notes, O’Connell:

…helped draw up the agreement that established it, spoke at public meetings to drum up support for it, invested in it, attended its first board meetings and, in 1836, was appointed its governor. He became an important figurehead for the new bank and there was even a proposal, not implemented, to put a bust of O’Connell on the bank’s notes.

The National Bank was created with the aim of injecting cash into the rural economy in Ireland, and its charter ensured that half of its returns would accrue to local shareholders in the country. O’Connell, not the best manager of financial affairs, ended up accruing huge personal debts to the bank and had to be quietly bailed out by several others (commencing a tradition of surruptitious banking amongst the nation’s major politicians).

Anyhow, the National Bank expanded across Britain and Ireland. In 1966 its Irish core was sold to the Bank of Ireland, and the English and Welsh branches were acquired by the National Commercial Bank of Scotland (which was a 1959 merger of the National Bank of Scotland and the Commercial Bank of Scotland). This, in turn, merged into the Royal Bank of Scotland in 1969, with the superfluous National Bank branches being turned into Williams & Glyn’s Bank the following year. (more…)

A Land, not a Republic

Bohemians seek to rename Czech Republic as ‘Czechia’

What are we to make of the growing movement against the name ‘Czech Republic’? It seems a welcome development, although one has a certain hesitancy in adopting the name ‘Czechia’ which somehow just doesn’t ring true from the English tongue.

Many will still automatically recall ‘Czechoslovakia’, an artificial country invented in 1918 which lasted a surprising seventy-four years. Its two successor states will celebrate their twenty-fifth anniversary of independence next year, and perhaps this landmark event has provoked some introspection regarding the country’s name.

Many will still automatically recall ‘Czechoslovakia’, an artificial country invented in 1918 which lasted a surprising seventy-four years. Its two successor states will celebrate their twenty-fifth anniversary of independence next year, and perhaps this landmark event has provoked some introspection regarding the country’s name.

It’s not that the Czech Republic is alone: there are plenty of countries whose official names included an adjectival demonym — the French Republic, the Italian Republic, and the Hellenic Republic spring to mind. But these three examples all have names that more readily spring to mind — France, Italy, Greece — and which are used more frequently then the official state names.

Besides the Czech Republic, the only other example of a country known only as ‘the [demonymic adjective] Republic’ is the Dominican Republic, which cannot be known as Dominica owing the nearby sovereign island of the same name. (The island Dominica was named after Sunday whereas the DR was named after Saint Dominic, the patron of its largest city.) Even the Central African Republic is often referred to as Centrafrique (in French, at least).

Is it a move against republicanism? Not especially. When neighbouring Hungary adopted its new constitution it dropped the state name ‘Hungarian Republic / Republic of Hungary’ in favour of just plain ‘Hungary’ while maintaining a republican form of government. More influential perhaps is that it’s often viewed as a bit tinpot-dictatorship to have the word ‘republic’ in your country’s everyday name. (more…)

Flag of an African Slaver

c. 1862-1866; hand-sewn cotton; 9 ft 2 in x 15 ft

Greenwich, London

The simple image of an African, garments aflutter, on a plain background provides a strikingly modern design as the commercial emblem of a firm engaged in the trade in human misery.

This flag was captured by Commodore Arthur Eardley-Wilmot while on anti-slavery operations off West Africa and given to his friend William Henry Wylde who supervised anti-slave-trade efforts at the Foreign Office in Whitehall.

The eradication of the slave trade is arguably the greatest peacetime achievement of the Royal Navy as well as powerful proof that the supremacy of economics can be overcome and made subject to morality. This is not just a possibility, but a necessary precondition for any humane and civilised order in society.

Smuts at Leiden

For quite some time, Leuven — in what is currently known as Belgium — was the only university in the Netherlands. It is still (barely, some argue) a Catholic university, and after the Protestant revolt sealed its rule over the northern part of the Dutch realms, William the Silent founded a university at Leiden as a Calvinist academy in 1575.

Leiden University has had strong links with South Africa from the earliest days. Ds. Johannes de Vooght — in the 1660s, the second leraar of Cape Town’s Dutch Reformed congregation — studied here, as did numerous predikante of that period and onwards, including Ds. Petrus van der Spuy, the first NGK minister to be born in South Africa.

South African politicians studied here aplenty: Sir Christoffel Brand (first Speaker of the Cape Parliament); Jan Brand (fourth president of the Orange Free State); Marthinus Steyn (sixth and final president of the O.F.S.); and Nicolaas Diederichs (third staatspresident of the Republic of South Africa).

Probably the first South African to be granted an honorary degree by Leiden (c. 1830) was Antoine Changuion, the founder of the Dutch language movement which advocated preserving Dutch as the cultural language of the Afrikaners against the emerging Afrikaans.

It was in 1948 that Leiden granted the greatest Afrikaner — Field Marshal Smuts — a Doctorate of Law honoris causa. Smuts was on his way back from Cambridge where he had been granted the honour of being installed as Chancellor of the University. Even Die Burger, a Nationalist paper opposed to his Verenigde party, found the event worthy of a caustic near-compliment:

“We may differ from him on many issues, but the honour which he has won for the Afrikaner does not leave us untouched.”

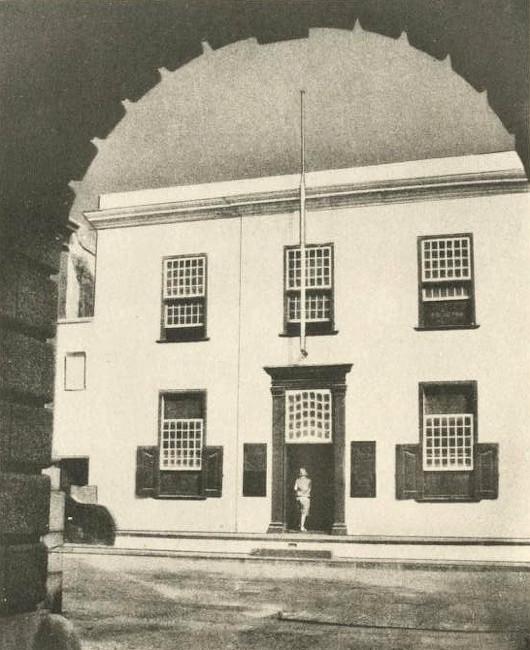

Keeromstraat 14

Keeromstraat 14, Kaapstad

This Cape Town house was built in 1751 for Hermanus Smuts who sold it on to Johan Jacobus Graaff, the woodworker who collaborated with South Africa’s greatest architectural duo, the sculptor Anton Anreith and the architect Louis Michel Thibault.

Thibault is believed to be responsible for the addition of the upper story and the current façade, seen above through an archway of the High Court.

The building next door was designed by the pioneering Afrikaner architect Wynand Hendrik Louw (1883-1967) for De Nederlandsche Club te Kaapstad, the city’s club for Dutch businessmen and expatriates. Louw was also the architect of the Dutch Reformed Church at Napier in the beautiful Overberg.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories