Tradition

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Secret Splendor

by Andrew Cusack (Weekly Standard, 13 September 2010)

Paintings for the Catholic Church in the Dutch Republic

by Xander van Eck

Waanders, 368 pp., $100

This book is the first major overview and exploration of the art of the clandestine Roman Catholic churches in the Netherlands. It is not a study of paintings so much as a history in which art is like the evidence in a detective story, or perhaps even the characters in a play. It might seem extraordinary that there was a place for large-scale Catholic art during the Dutch Republic: Pre-Reformation churches had been confiscated and were being used for Calvinist services, while priests offered the Mass secretly in makeshift accommodations. Eventually a bargain between Dutch Catholics and the civil authorities emerged, trading Catholic nonprovocation in exchange for private toleration of the practice of the faith. Catholics began to purchase properties which, for all outward appearances, maintained the look of ordinary residences but whose interiors were transformed into resplendent chapels and churches.

Xander van Eck provides verbal portraits (often accompanied by contemporaneous painted ones) of several of the important clerics of the Dutch church during this period: Sasbout Vosmeer, the Delft priest influenced by St. Charles Borromeo; Philippus Rovenus, the vicar-apostolic who placed greater emphasis on clandestine parishes having specially dedicated churches, even while they kept an outward unecclesiastical appearance; and Leonardus Marius, the priest who promoted devotion to the 14th-century Eucharistic “Miracle of Amsterdam.” Marius was of such prominence that, after his death, shopkeepers rented out places on their awnings for punters to view his funeral procession. Van Eck includes a handful of amusing asides, such as the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Netherlands as a result of their constant discord with the secular clergy. Mass continued to be offered at the Jesuit church of De Krijtberg in Amsterdam “in the profoundest secrecy” — thus creating a clandestine church within a clandestine church!

The role of the clergy in sustaining the Dutch Church is unsurprising, but it is instructive to learn how instrumental laity were to keeping alive the light of Catholic faith in the Netherlands at the time. Clandestine churches relied on the generosity of Catholic families. Prominent families often provided their own kin as consecrated virgins who brought large dowries into the church, or as priests with suitable inheritances to maintain or endow clandestine parishes. The clandestine church of ’t Hart in Amsterdam, built by the merchant Jan Hartman for his son studying for the priesthood, is still open today as the Amstelkring Museum and Chapel of “Our Lord in the Attic.”

While van Eck explores the extent to which Dutch art from the period followed European norms, an emphasis on the particularity of the art of the clandestine church is to be expected. The sheer volume of art produced during this period — for just three Amsterdam churches alone there were 16 altarpieces — is partly explained by the phenomenon of “rotating altarpieces.” The paintings above the altar would be changed according to the feast or season — a practice sometimes seen in Flanders or parts of Germany but never nearly so widespread as in the Netherlands proper.

Constrained as clandestine churches were on the narrow plots typical of Dutch cities, there was no room for side chapels that might include the large funerary monuments prominent families would construct. This left altarpieces as the most convenient way for munificent Catholics to provide art for their churches: Rotating the altarpieces provided a handy way of displaying numerous commissions rather than just the donation of whoever had been generous most recently, and the themes of these commissions tended to vary in appropriateness to different feasts and seasons.

Some found fault with this method: Jean-Baptiste Descamps, visiting Antwerp in 1769, complained that the most interesting altarpieces were not permanently displayed and were more likely to be damaged in the process of being moved so often.

While the accomplishment and ingenuity of Dutch Catholics in keeping their faith during the Republic was striking, the ill-defined administrative structure of the persecuted church allowed conflicts between clerics to thrive, and doctrinal disputes emerged and festered. The disputes over Jansenism that swept over France and the Netherlands, for example, only exacerbated the administrative problems of the clandestine church. Like their Calvinist compatriots, the Jansenists tended to frown on indulgences, the veneration of saints, recital of the rosary, and private acts of worship, putting greater emphasis on the Scriptures and a more rigorous asceticism. As van Eck points out, this difference in emphasis was not exclusive to the Jansenists, but their novelty (and their heresy) was in preaching the exclusivity of their approach above all others.

Numerous vicars-apostolic had written to Rome arguing for the re-establishment of the episcopacy in the Netherlands to solve the disputes over authority, but their appeals fell on deaf ears. In 1723 a large portion of the Jansenist clergy reinstituted the episcopacy by electing an archbishop of Utrecht from their number — and were subsequently excommunicated, splitting the clandestine church and its clergy in two. (This excommunicated rump united with the opponents of papal infallibility in the following century to form a body that still calls itself the Old Catholic Church.)

When one looks at all this glorious art, not to mention the lives and pious ingenuity of the persecuted, it’s difficult not to feel a little poorer, considering the fruits of our churches in an ostensibly free era. Why does the church today commission painters who are either mediocre or trendy — or both? Artists like Hans Laagland and Leonard Porter show that good art — good liturgical art, even — is possible today, but commissions from the church for traditional artists are sadly few.

Roots and Permanent Interests

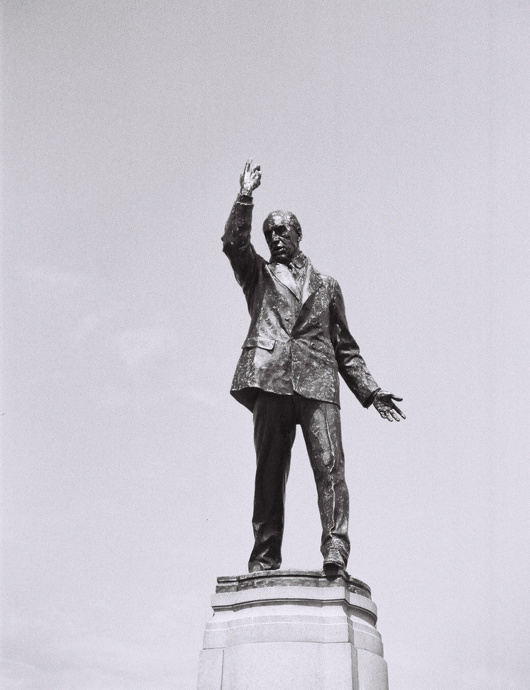

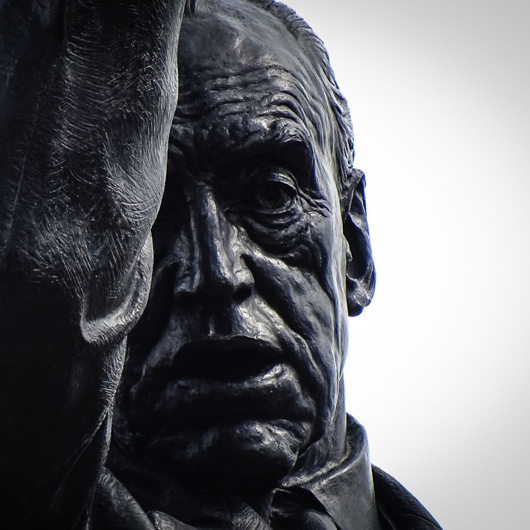

Carson at Stormont

Few statues in Ireland are as dramatic as that of Edward Carson at Stormont. The unionist leader is depicted in amidst an oratorical flourish, doubtless in one of his speeches to mass meetings condemning home rule.

In the 1910s as the rebirth of an Irish parliament looked more likely, Carson took up the cause of fighting home rule on behalf of Ireland’s large Protestant minority who feared Catholic domination. When the anti-home rulers realised the cause was losing, they retreated from Irish unionism to Ulster unionism. If home rule was to be granted, Ulster must be exempted. In the end this meant home rule was granted to a parliament covering two-thirds of the Irish province of Ulster — six counties that would henceforth be known as Northern Ireland.

“His larger than life-size statue,” one historian wrote, “erected in his own lifetime in front of the Northern Ireland parliament at Stormont, symbolizes the widely held perception that Northern Ireland is Carson’s creation.”

This is of course the great irony, given that Edward Carson was a Dublin boy through and through. While instrumental in ensuring northeastern Ireland’s exemption from an Irish parliament, Carson actually had little to do with the entity thereby created. When offered the premiership of Northern Ireland he declined it on the grounds of having no real connection with the place.

Craig, not Carson, is the true father of Northern Ireland; he imbued the new statelet with a sense of bigotry and tribal hatred that Carson lacked. The Dubliner urged Ulster’s new leaders to treat the province’s Catholics well.

“We used to say that we could not trust an Irish parliament in Dublin to do justice to the Protestant minority,” Carson said. “Let us take care that that reproach can no longer be made against your parliament, and from the outset let them see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from a Protestant majority.”

Alas, it became apparent to Carson that discrimination and inequality were becoming in-built within Northern Ireland’s government, from the Parliament at Stormont down to the lowest forms of local government. He confided to a Catholic friend in London that rather than being an integral part of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland was turning into “a second-class dominion”.

After partition Carson was created a British judge and accordingly ennobled. (Disappointingly the plaque on his Dublin birthplace next to Conradh na Gaeilge refers to him by the incorrect style of ‘Lord Edward Carson’.) He settled at Clever Court near Minster-in-Thanet, Kent, and never lived in his native Ireland again.

Nonetheless he was held in awe and reverence by the Protestant Unionists of Ulster, who commissioned the striking statue by Leonard Stanford Merrifield that stands in front of Parliament Buildings, Stormont — now home to the Northern Ireland Assembly. It was unveiled by Craig, by then ennobled as Lord Craigavon, while Carson was alive and present in July 1932, joined by a crowd of 40,000 well-wishers.

Carson died in 1935 and was given the rare honour of a state funeral. HMS Broke brought his Union-Jack-draped coffin back to Ireland — albeit to Belfast — and he was interred in the Anglican Cathedral of St Anne. Northern Ireland claimed him even in his final burial: soil from each of its six counties was scattered on his coffin when laid to rest in the tomb.

Still his statue stands at Stormont, gesturing stridently as if to challenge an entire province — a province he by his own description had little to do with. Calls for it to be removed emanate occasionally from typically boring quarters and have so far been rebuffed — wisely. Carson, unlike many of those who cherished his memory, was an honourable man, and it is a pity it took so long for the Protestants of Ulster to heed the advice of their confrère from Dublin.

St Nicholas, Our Patron

As by now you are all well aware, today is the feast of Saint Nicholas, the patron-saint of New York. His patronship (patroonship?) over the Big Apple and the Empire State date to our Dutch forefathers of old – real founding fathers like Minuit, van Rensselaer, and Stuyvesant, not those troublesome Bostonians and Virginians who started all that revolution business.

Despite being Protestants of the most wicked and foul variety, the New Amsterdammers and Hudson Valley Dutch maintained their pious devotion to the Wonder-working Bishop of Myra and kept his feast with great solemnity.

After New Netherland came into the hands of the British (and was re-named after our last Catholic king) the holiday continued to be celebrated by the Dutch part of the population, and was greatly popularised in the early nineteenth century by the publication of a curious volume entitled A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty which purported to be by one Diedrich Knickerbocker.

In fact it was by Washington Irving, the first American writer to make a living off his pen, who did much to popularise St Nicholas Day in New York as well as to revive the celebration of Christmas across the young United States.

While, aside from hearing Mass and curling up with a clay pipe and a volume of Irving (being obsessive, I have two complete sets) here are a few links that shed some light on New York’s heavenly protector.

Historical Digression: Santa Claus was Made by Washington Irving

New-York Historical Society Quarterly: Knickerbocker Santa Claus

The History Reader: The 18th Century Politics of Santa Claus in America

The New York Times: How Christmas Became Merry

The Hyphen: Thomas Nast’s Illustrations of Santa Claus

– plus: Santa Claus and the Ladies

National Geographic: From Saint Nicholas to Santa Claus

Previously: Saint Nicholas (Index)

Knickerbocker Spires

Before the age of the skyscrapers, New York’s church spires dominated the horizon and dwarfed their neighbours just like in the medieval towns and cities of the old world — as this photo from the 1900s shows.

Here St Patrick’s Cathedral holds court, with the St. Nicholas Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church poking up a few blocks down Fifth Avenue.

Slightly north on that same boulevard sits the grand renaissance palazzo of the University Club, with the spire of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church poking up behind it.

Inside Governors Island

This intriguing little island in New York Harbour has always held something of a fascination for me — viz. articles previous on the subject. Aside from its interesting history there is the matter of the complete lack of foresight in ending its military use as well as the failure to imagine a future use suitable to its history and, if the word is not hyperbole, majesty.

Gothamist recently featured a new peek inside some of the abandoned buildings on Governors Island, a mere selection of which are reproduced here. (more…)

Hollandic Fever

Adapted from the Deborah Moggach novel of the same name, ‘Tulip Fever’ is a curious concoction. Some of the plot holes are so big you could drive a coach and horses through them. For example, how is it that – in Calvinist-controlled seventeenth-century Amsterdam – there is a massive Catholic convent perfectly accepted by everyone and operating as if nothing is out of place? It’s the size of Norwich Cathedral! (In fact, it is Norwich Cathedral – this entire production was filmed in Great Britain.)

The often excellent Chrisoph Waltz is curiously mismatched with his role here: a little bit too much of a parody of the proud, pious Amsterdam merchant in the start, which makes his eventual transformation a little unconvincing. The plot also shows little of the brilliance of its co-writer Sir Tom Stoppard. (In fact, there’s a bit too much plot.) At least Dame Judi Dench is effortless in her role as the unnamed Abbess of St Ursula. Tom Hollander is thrown in for a laugh, in a role suited to his abilities.

For curiosity’s sake the most interesting casting choice was Joanna Scanlan, known as the useless press officer at DOSAC in ‘The Thick of It’. Here she is the dressmaker Mrs Overvalt, but she was Vermeer’s cook Tanneke in ‘Girl with the Pearl Earring’. If my rudimentary calculations are correct, this means she has been in two-thirds of twenty-first-century films set in the Dutch seventeenth century.

It is, however, a beautifully shot production, for which I suspect we have the cinematographer Eigil Bryld to thank. (He’s worked on one seventeenth-century film before, and on another set in the Low Countries.) Bookended by scenes of Friedrichian romanticism (I’m into that) the film encourages me in my deeply felt belief that we need to revive seventeenth-century Dutch domestic architecture as a style.

Mugabe and Friends

The recent election (such as it was) in Zimbabwe brought to mind the Nando’s television advert of Robert Mugabe and his old mates.

Gaddafi, Mao, Saddam, and Idi Amin all make an appearance, and even (somewhat incongruously) die ou krokodil, P.W. Botha.

Classical New England

A reminder that Russell Kirk once described the piano nobile of the Old State House in Hartford, Connecticut, as:

“perhaps the most finely proportioned rooms in all America”

Given the elegant restraint and classical detail of the old Senate chamber, it’s hard to disagree.

The Governor’s Room

Pursuant to my post of John Bartlestone’s photographs of City Hall, I came across this photo the other day and it reminded me that this is still one of my favourite rooms in all New York. There’s something about that particular shade of green. I previously wrote about this suite of three rooms in 2006.

The above photo is by Ramin Talaie while below, in 2010, Mayor Bloomberg inspects a city flag being sent to a New Yorker serving in Afghanistan as reported by the Daily News.

The late & much-missed New York Sun also reported on the portraits hanging in City Hall in 2008.

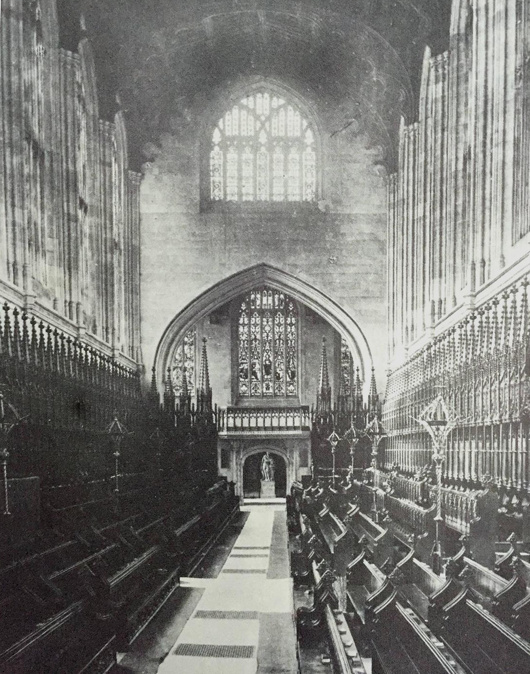

Eton College Chapel

The interior of Eton’s chapel has changed markedly over the past hundred or so years, mostly so thanks to the rediscovery of the priceless medieval wall paintings which had been hidden for centuries by the choir stalls. Painted in the Flemish style in 1479–87, they were whitewashed over by the college barber in 1560 on orders from the wicked new Protestant authorities who had taken over this Catholic school.

The wall paintings were rediscovered in 1847 but it wasn’t until 1923 that the stall canopies in the photograph above were permanently removed, allowing the medieval paintings to be cleaned, restored, and permanently viewed.

In addition to this, in the 1880s (after this photograph was taken) the Great Organ was installed in the broad entrance arch between the narthex and the body of the chapel. The Victorians very handsomely painted it in the medieval fashion and it fits in rather well.

More recently, most of the stained glass was blown out by a German bomb landing in the adjacent Upper School in 1940. A decade later, deathwatch beetles claimed the wooden roof, which was then replaced by fan vaulting (of stone-fronted concrete) in line with the original intentions of Eton’s holy founder, King Henry VI.

Earls, Shires, Hides, and Hundreds

What the Practice of ‘Pricking the Lites’ Tells Us About Territorial Division in Anglo-Saxon England

As cheekily noted by Ned Donovan on his Twitter feed, HM the Q has recently engaged in the old practice of ‘pricking the lites’ to appoint High Sheriffs for the three ceremonial counties of Lancashire, Greater Manchester, and Merseyside. But in order to know what ‘pricking the lites’ is it’s worth looking at the territorial division of Anglo-Saxon England and the old offices that emerged therefrom.

In those days, the land was divided into hides, a hide being the amount of land on which a family lived and supported itself. Ten hides together were known as a tithing, and ten tithings were collectively a hundred.

As hundreds go, the best-known today are the Chiltern Hundreds because of the parliamentary role they play. Members of Parliament are not allowed to resign, but nor are they allowed to hold an office of profit under the Crown.

So whenever an MP wants to resign, he or she is appointed Crown Steward and Bailiff of the three Chiltern Hundreds of Stoke, Desborough, and Burnham and, having accepted such office, is deemed to have disqualified themselves from continuing to sit in the House of Commons. (The Manor of Northstead is also used alternately with the Chiltern Hundreds.)

Anyhow, each hundred was supervised by a constable, and groups of hundreds were collected into shires. Each shire was overseen by an earl, of whom the French equivalent is a count, so after the Normans turned up shires became more often known as counties. These now divvy up territory across the English-speaking world, from Kenya to California.

Each level of these Anglo-Saxon divisions had a relevant court for decision-making, and the officer who administered or enforced these decisions was known as the reeve. Amongst these titles – town-reeve and reeve of the manor, etc. – there was the shire-reeve, or sheriff as it was contracted.

In the 1970s, for reasons unknown to me, all the sheriffs in England & Wales were elevated to high shrievalties.

Every February or March, a parchment is prepared for the Queen in her capacity as Duke of Lancaster with three names of candidates for high sheriff in the three current ceremonial counties covered by the old duchy. This parchment is known as the lites (a cognate of ‘list’, I believe).

At a meeting of the Privy Council, the Queen takes a silver bodkin and pricks the parchment next to the name of the candidate she chooses to be high sheriff. In practice, this is always the first name on the list, and customarily the following names move up a notch and serve in later years.

A similar process takes place for the Duke of Cornwall to appoint their high sherriff but without the aid of the Privy Council.

Trad Flag

When a cardinal dies his galero is suspended aloft above his tomb to slowly rot and wither away, thus showing the eventual fate of all earthly things. Unlike galeros, the construction and manufacture of flags has “advanced” much in the past century in the sense that they are now made of virtually indestructible materials. This renders them useful for long-term outdoor display but is somewhat lacking in texture, feel, and look.

Earlier flags were made of materials that allowed them to grow old gracefully adding dignity with each passing year, whereas today more often than not they are printed on synthetics. Sewn flags are still available, if at slightly greater cost, and are a good way to keep things smart.

I love a good trad flag though, and Oriel College Boat Club – a festive institution well known for the quality of both its rowing and its conviviality – has a perfect example of one (above and below). From my admittedly unexpert eye, I’d say it’s printed on cotton. Perhaps others know more.

A handsome banner that I dare say outsmarts any of its neighbours in the row of boathouses along the Isis.

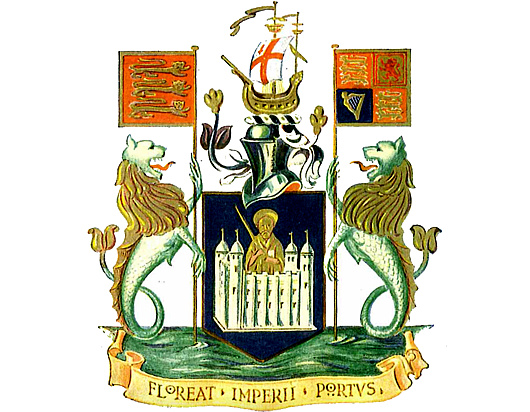

The Port of London

Officially there are or have been various Londons: first the City of London, founded in AD 43 and a mere square mile to this day, then the County of London created in 1889, and the creature called Greater London has also existed in varying shapes and forms since 1965.

But there is also the Port of London, which has existed since the first century and was once the busiest port in the world, bringing the riches of empire to the metropolis from the four corners of the earth.

The arms of the City of London, London County Council, and Greater London Council.

All these Londons, of course, have over the centuries been granted or assumed their own coats of arms as heraldic emblems of their importance. The Port of London Authority was created in 1908 by an Act of Parliament which some scholars argue is the first law in the world mandating codetermination or workers’ participation in the board.

Its coat of arms was granted a year later in 1909 and features on its shield Saint Paul, the patron saint of London bearing his usual sword, issuing forth from the Tower of London.

Its coat of arms was granted a year later in 1909 and features on its shield Saint Paul, the patron saint of London bearing his usual sword, issuing forth from the Tower of London.

The crest above the shield is a galley bearing on its mainsail the arms of the City of London — the Lord Mayor is ex officio the Admiral of the Port of London.

Sea lions act as supporters, also bearing standards of the royal arms of England and of the United Kingdom, while the motto proclaims in Latin May the Port of the Empire Flourish.

For proper heraldry nerds, the arms are blasoned:

Shield: Azure, issuing from a castle argent, a demi-man vested, holding in the dexter hand a drawn sword, and in the sinister a scroll Or, the one representing the Tower of London, the other the figure of St Paul, the patron saint of London.

Crest: On a wreath of the colours, an ancient ship Or, the main sail charged with the arms of the City of London.

Supporters: On either side a sea-lion argent, crined, finned and tufted or, issuing from waves of the sea proper, that to the sinister grasping the banner of King Edward II; the to the sinister the banner of King Edward VII.

Befitting the Port of the Empire, the Authority built a grandiose headquarters at 10 Trinity Square, overlooking the Tower of London featured in its coat of arms.

The PLA moved out ages ago and the building is now a hotel, but it often features in films and television as a government (most prominently in the 2012 James Bond film ‘Skyfall’).

The Port of London Authority has its own flag (above) as well as its own ensign — a blue field with a Union Jack in the canton and in the fly a golden sea lion bearing a trident. Distinctive pennants also exist for the Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Authority. (These can be seen here.)

After its foundation the PLA rationalised the layout and organisation of London’s dock system, and their significant constructions allowed the Port to displays its arms on numerous buildings. One such display (above) was recently sold by Westland London.

The main shipping terminal of London is now far down-river at Tilbury and the Authority no longer owns any docks. Its duties however are still numerous — control of Thames ship traffic, navigational safety, pier & jetty maintenance, and conservation — so the century-old Authority still keeps itself quite busy looking after a millennia-old port.

The Steps of the Throne

Who may sit on the steps of the throne in the House of Lords?

Much was made of the Prime Minister’s decision to sit in the House of Lords when they were going through stages of the bill to invoke Article 50 last year. Theresa May had the right to sit on the steps of the throne in the Lords chamber by virtue of being sworn to the Privy Council, as all holders of the four Great Offices of State are (and usually their opposition Shadows as well).

But who else is granted the privilege of lodging their posterior in such a prominent locale?

The Companion to the Standing Orders and Guide to the Proceedings of the House of Lords provides some guidance:

1.59 The following may sit on the steps of the Throne:

· members of the House of Lords in receipt of a writ of summons, including those who have not taken their seat or the oath and those who have leave of absence;

· members of the House of Lords who are disqualified from sitting or voting in the House as Members of the European Parliament or as holders of disqualifying judicial office;

· hereditary peers who were formerly members of the House and who were excluded from the House by the House of Lords Act 1999;

· the eldest child (which includes an adopted child) of a member of the House (or the eldest son where the right was exercised before 27 March 2000);

· peers of Ireland;

· diocesan bishops of the Church of England who do not yet have seats in the House of Lords;

· retired bishops who have had seats in the House of Lords;

· Privy Counsellors;

· Clerk of the Crown in Chancery;

· Black Rod and his Deputy;

· the Dean of Westminster.

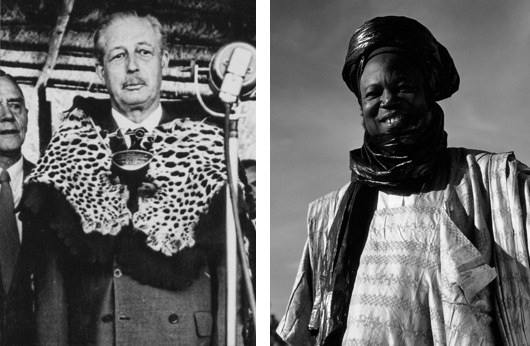

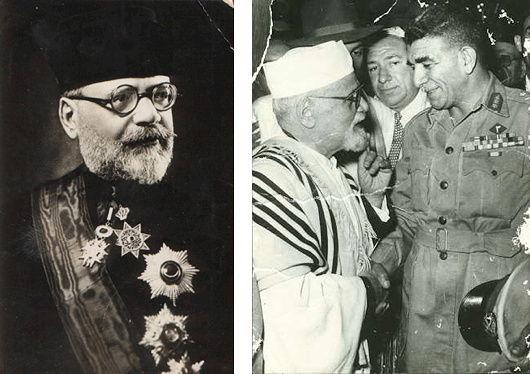

Supermac and the Sarduana

Macmillan’s Attitude to Class and Race in the Late Empire

Left: Harold Macmillan touring Africa in 1960; Right: Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Sarduana of Sokoto.

Staying over with some Kenyan friends in Wiltshire the other day, the old observation came up that, after the war, the officers settled in Kenya while the sergeants went to Rhodesia. While some of the leading lights of UDI had, in fact, been officers — Ian Smith an obvious case — it’s interesting to note that most of them came from humble backgrounds.

“Smithie” was born well-off in Rhodesia but his father had been a butcher’s son who went out to Africa and made good. Clifford Dupont, the first president of the Rhodesian republic, was born in London of poor East End Huguenot stock. His father had done well in the rag trade and got his son to Cambridge; Clifford became an artillery officer before emigrating to Africa.

Rhodesian Prime Minister Roy Welensky’s father was a Russian Jewish horse smuggler who married a ninth-generation Afrikaner. Roy was the couple’s thirteenth son, and left school at 14 to work on the railways and found success through the trade union movement.

Harold Macmillan, meanwhile, was a Guards officer and Old Etonian who had studied at Oxford. His famous ‘Wind of Change’ speech was just part of the British prime minister’s grand tour of Africa. “Supermac” started in Nigeria, where — unlike in some other parts of the continent — much of the native aristocracy had been preserved and coopted throughout colonial rule.

Proving Orwell’s observation that the English are the most class-ridden nation on earth, the PM felt comfortable amongst black African patricians in a way he couldn’t amongst members of the ruling white African elite from humble backgrounds.

In one of the ICBH’s oral history group discussions, Perry Worsthorne relates:

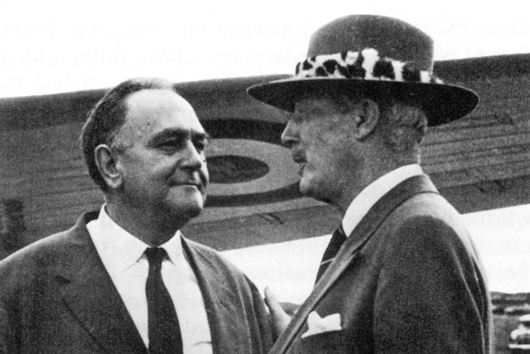

Somebody at some point has to mention, in any discussion of British politics, snobbery and class. I remember travelling and reporting on the ‘Wind of Change’ speech. We went to stay on the last bit, just before going on to Salisbury, was it the Sardauna of Sokoto who was he the premier of the Northern Nigerian region. Macmillan talked to us after he had seen him, he was flying on to Welensky the next day.

Macmillan used to have a sundowner with the correspondents covering his trip, and over whisky and sodas he told us how much more at home he felt with the Sardauna, who reminded him of the Duke of Argyll – ‘a kind of black highland chieftain’ – than he would feel in Salisbury as the guest of a former railwayman, Sir Roy Welensky. Snobbery, pure snobbery.

The British metropole was always ready to make racial distinctions and discriminate accordingly, yet it still tended to look upon outright racism with an air of disdain, as something slightly unsporting (or worse: foreign).

In the imperial periphery, racial attitudes amongst whites often differed greatly from Britain. This was most obviously so in South Africa, which for all intents and purposes embarked upon a radical revolutionary rejection of the British model of governance from 1948 with the implementation of apartheid. Rhodesia, needless to say, was another exception, if arguably more mild. “How different it would all have been,” Worsthorne somewhat patronisingly wondered, “if Ian Smith had been a gentleman.”

Meanwhile Nigeria’s Sir Ahmadu Bello — the Sarduana of Sokoto — was a statesman of cautious action, and his refusal to become Nigerian prime minister upon independence (he preferred sticking to his existing role as the powerful premier of the northern province) sadly deprived the federal state of the wisdom and experience which may have prevented its later descent into disarray. He was murdered by Major Nzeogwu during the 1966 coup d’état.

Differences of race or class aside, it’s telling that both the white low-born railwayman Welensky and the black patrician Bello ended up as knights of the realm.

St Paul’s Survives

Crossing the Thames as I walked home from the pub last night, I looked down the river and saw the sturdy dome of St Paul’s standing out, illuminated in the winter night.

As it happens, it was exactly seventy-seven years ago last night — on the 29th of December 1940 — that the iconic photograph often called ‘St Paul’s Survives’ (above) was captured.

Hopeful as that sight must have been, it was a pretty grim time. But four and a half years later (below) the cathedral was illuminated not by the lights of enemy firebombs but by great searchlights forming a massive ‘V’ in the sky: it was 8 May 1945 — Victory in Europe.

Another year gone. We’ve survived.

“Events did not choose the terrorists; powerful white people did.”

Helen Andrews on Zimbabwe

Robert Mugabe leading Ian Smith into the Zimbabwean parliament, 1980.

It is rare to find journalism as informed and insightful as this piece on Zimbabwe by Helen Andrews in National Review. In the aftermath of Mugabe’s clumsy downfall and his succession by a powerful apparatchik and experienced political operator, Helen explores the Rhodesian crisis and attempts to answer the question: could it really have gone any other way?

Any idea that liberal reform on the part of the Rhodesian state could have saved it is a non-starter, because the anti-imperialists were implacable and — I do not know a gentle way to put this — they were quite happy to lie. I do not mean just the professional liars of the Soviet propaganda shop, or the pundits who lazily referred to the Rhodesian system as “apartheid,” or the guerrillas who told Shona villagers that ZANU had successfully dynamited the Kariba Dam, or the foreign journalist who scattered candy around a garbage bin and captioned the resulting photo “Starving children searching for food in Salisbury.” Ralph Bunche had a doctorate from Harvard, a Nobel Peace Prize, and a co-author credit on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and when it came to imperialism, he lied.

“Colonial authorities like the noted Englishman, Lord Lugard, doubt that the African race, whether in Africa or America, can develop capability for self-government.” When I first read that in Bunche’s 1936 pamphlet “A World View of Race,” I felt a lurking suspicion that I had read a sentence of Lord Lugard’s beginning with the very words “The method of their progress toward self-government lies…” I had. His next words are “along the same path as that of Europeans.” Even making allowances for CTRL-F’s not having been invented yet, Bunche’s remark is plain slander. With Harvard Ph.D.s pulling stunts like this, it is hard to summon much indignation at a garden-variety diplomatic lie like the U.N. claim, by which sanctions were justified, that Rhodesia had committed an act of aggression by maintaining its status quo.

She does go a little easy on Smith, who despite his many strengths was just as willing to play fast and easy with the truth. (He was a politician, after all.) But then as we are so used to hearing that Smithie was a little Hitler it’s a welcome restorative.

When I moved to South Africa, I did so at least in part because I wanted to see it before it became “the next Zimbabwe”. Having come back, I was impressed by the relative robustness of many of its institutions, and the certain robustness of many of its people. Rather than a Zimbabwe-style collapse, South Africa seemed destined for a slow, ungainly descent into perpetual malaise.

The recent ascent of Cyril Ramaphosa – who on behalf of the ANC ran rings round the NP negotiators during the transition talks of the early ’90s – gives hope to many. I’m too cautious to be optimistic, but Mr Ramaphosa is clever, intelligent, skilful, and more likelier to keep the unions on side.

“Get me ze Führer!”

Stereotypes of Nazi generals in British war films

“The reason for my uniform being a slightly different colour to yours

is never explained.”

The British are, of course, obsessed with the Nazis. There are many reasons for this, amongst which we must include the large number of really quite good war films produced during the 1950s and 1960s.

For some indiscernible reason these movies have the virtue of being eternally rewatchable and many a cloudy Saturday afternoon has been occupied by Sink the Bismarck!, Where Eagles Dare, or The Colditz Story.

The genre also deploys with a remarkable regularity a number of familiar tropes of ze Germans which the above clip from a British comedy sketch programme (introduced to me by the indomitable Jack Smith) aptly mocks.

Nahum Effendi and Cairo’s Lost World

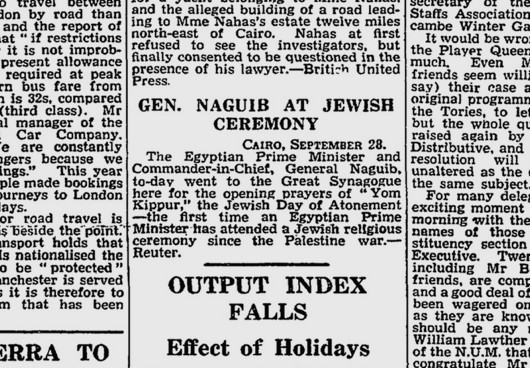

Stumbling across the newspaper clipping above was a sad reminder of a lost world. Taken from the front page of the Manchester Guardian of Monday 29 September 1952, it describes the Egyptian leader General Naguib attending a Yom Kippur service just two months after the coup that overthrew the country’s monarchy. None of the Jewish places of worship in Cairo are known as the “Great Synagogue”, so I presume this must have been the Adly Street Synagogue (Sha’ar Hashamayim).

The Chief Rabbi of the Sephardic community in Egypt at the time would have been Senator Rabbi Chaim Nahum Effendi. A creature of the Ottoman world, Rabbi Nahum was born in Smyrna in Anatolia, went to yeshiva in Tiberias on the Sea of Galilee, and finished his secondary education in a French lycée.

After earning a degree in Islamic law in Constantinople, he started his rabbinic studies in Paris while also studying at the Sorbonne’s School of Oriental Languages. Returning to Anatolia he was appointed the Hakham Bashi, or Chief Rabbi, of the Ottoman empire in 1908 and honoured with the title of effendi.

After that empire collapsed, Rabbi Nahum was invited to take up the helm of the Sephardic community in Egypt in 1923. A natural linguist and a gifted scholar, the chief rabbi’s talents were apparent to all, and he was appointed to the Egyptian senate as well as being a founding member of the Royal Academy of the Arabic Language created to standardise Egyptian Arabic.

Rabbi Nahum (front row, third from left) at the foundation of Egypt’s Arabic academy.

The foundation of the State of Israel was a godsend for many Jews but spelled the beginning of the end for Egypt’s community. Zionists were a distinct minority among Egyptian Jews — many of whom were part of Egypt’s (primarily anti-British) nationalist movement — but Israel’s defeat of the Arab League in the 1948 War embarrassed Egypt’s ruling classes and stoked anti-semitism amongst the populace. Violent attacks against Jewish businesses were tolerated by the authorities and went uninvestigated by the police. Unfounded allegations of both Zionism and treason were rife, and discriminatory employment laws were introduced.

The 1952 Revolution did not improve things, as the tolerant but decaying monarchy was replaced by a vigorous but nationalist and pan-Arabist military government. Faced with such continuing depredations, the overwhelming majority of Jewish Egyptians fled — to Israel, Europe, and the United States. Rabbi Nahum eventually died in 1960, by then something of a broken man I imagine.

Cairo was once a thriving cosmopolitan city of Muslims, Christians, and Jews — and many communities of outside origin. The Greeks, who first arrived twenty-seven centuries ago and in 1940 still numbered tens of thousands, have all left. The futurist Marinetti was the most famous of the Italian Egyptians, whose numbers in the 1930s were numerous enough to warrant several branches of the Fascist party. Since the 1952 Revolution they are all gone too. Some Armenians remain, but not many. As for Jews, there are six left in Egypt.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories