Tradition

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

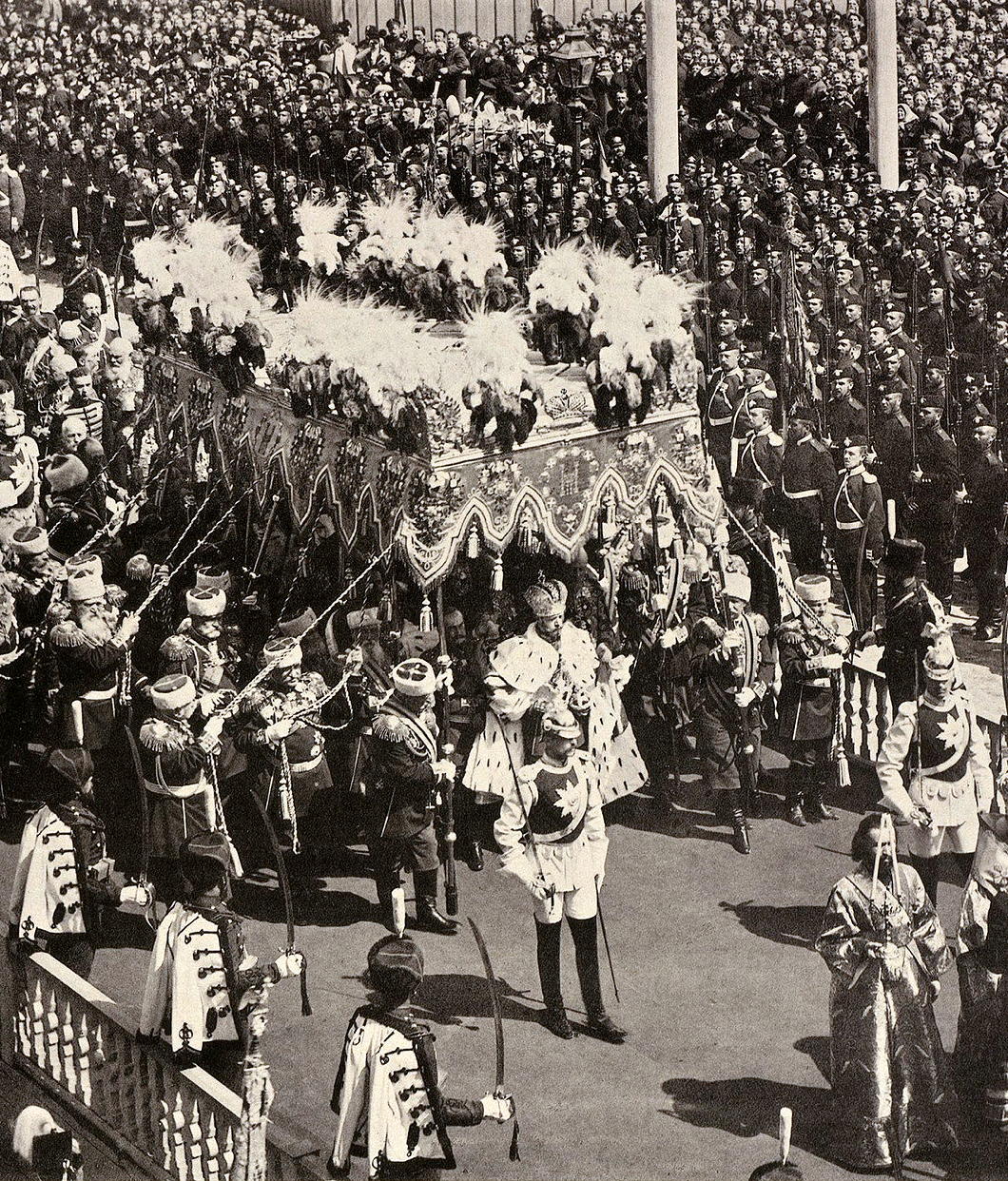

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The George

“FORTUNATE IS SOUTHWARK in her possessions,” Sir Albert Richardson wrote, “for she holds in this fragment a key to the aspect of her many vanished inns…”

The George Inn features largely in the deep psychogeography of Southwark, ours the most ancient of boroughs. Here is the greatest living remnant of the coaching inns of old, even if much reduced in form. The current structure dates from the 1670s but we know an inn on this site was well established by the 1580s. It is now in the possession of the National Trust, but is a functioning Greene King pub where you can find a good pint.

Up and down our High Street, for centuries merchants, travellers, traders, and revellers would slake their thirst in a procession of pubs, inns, and taverns. English pilgrims heading to Canterbury would start off here, and recent arrivals to London from the Continent would make their first acquaintance with England’s capital by arriving at “The” Borough after journeying from the Channel ports.

“One enters the inn yard with pleasurable anticipation,” Sir Albert continues in his 1925 volume, The English Inn, Past and Present; A Review of Its History and Social Life.

“There is fortunately sufficient of the old building remaining to carry the mind back to the days of its former prosperity. There are the sagging galleries, the heavily-sashed windows and the old glass in the squares. The rooms are panelled. In the dining-room are the pews, and the bar is typical.”

In Richardson’s time, just a century ago, these rooms would have often been full of hop growers from Kent and the hop merchants who traded with them, though they are all gone now.

And yet, some things have not changed:

“Here we can obtain old English fare, and, heedless of the beat of London, commune with ghostly frequenters to whom the place was at one time a reality.” (more…)

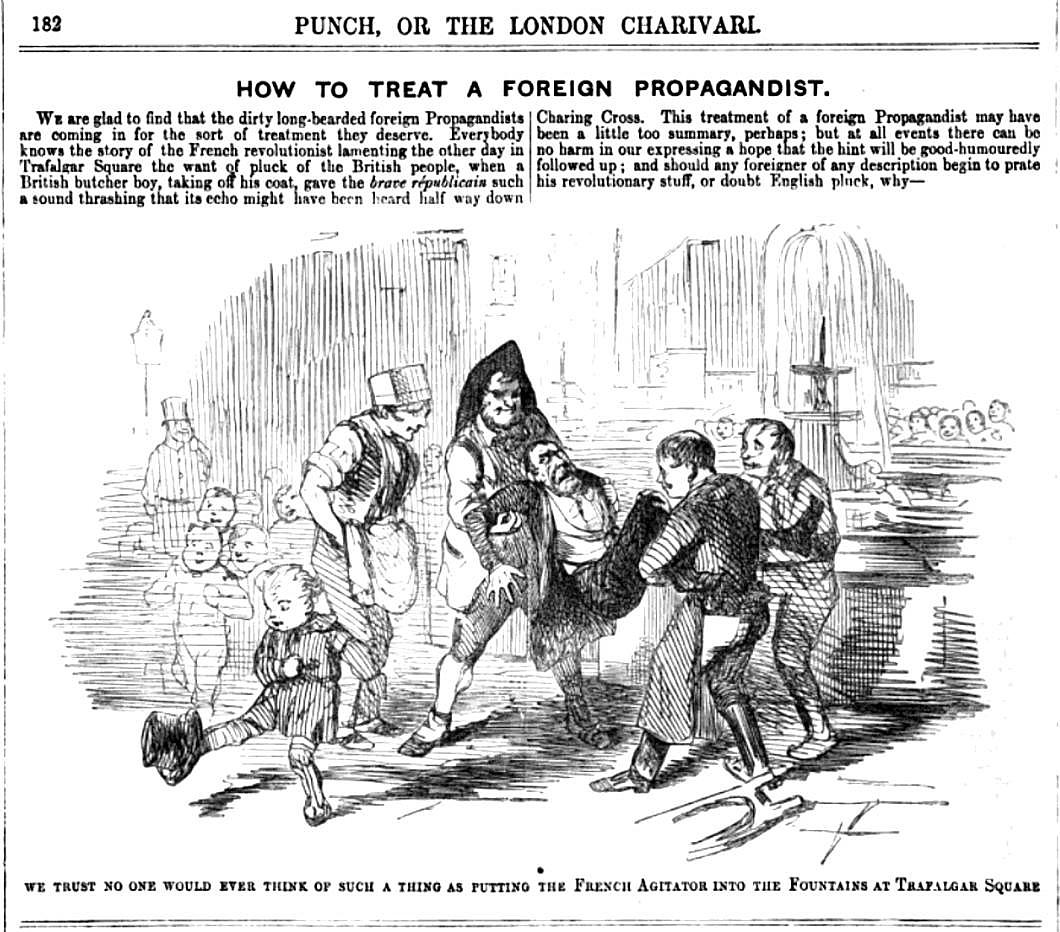

‘We trust no one would ever think of such a thing’

Ladies and gentlemen of ‘the left’, whether foreign or domestic, have long groaned over the earnest patriotism and lack of zeal for revolutionary destruction amongst the British working classes.

As this snippet from an 1848 issue of Punch shows, when the fighting power of Britain’s workers is unleashed, it’s usually channelled against the zealots and in defence of hearth of home:

Everybody knows the story of the French revolutionist lamenting the other day in Trafalgar Square the want of pluck of the British people, when a British butcher boy, taking off his coat, gave the brave républicain such a sound thrashing that its echo might have been heard half way down Charing Cross.

This treatment of a foreign Propagandist may have been a little too summary, perhaps; but at all events there can no harm in our expressing a hope that the hint will be good-humouredly followed up; and should any foreigner of any description begin to prate his revolutionary stuff, or doubt English pluck, why —

Weiter vorwärts

Mexican Diplomats

Don Manuel Iturbe, envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary, sits wearing the full civil uniform of an ambassador while the two attachés, Don Miguel Iturbe and Don Juan Beistegui, stand wearing lower grades of diplomatic dress.

All three wear the Order of St Stanislaus — the Polish royal order incorporated into the Romanov orders in 1832.

The records of the Mexican congress shows that Manuel Iturbe was authorised to accept Grand Cross of the order while Miguel (who I presume was Don Manuel’s son though I can’t confirm) and Juan Beistegui had to settle for the ordinary Cross of St Stanislaus.

Christmas Tree

The Other Modern in Jewish Amsterdam

Jacobus Baars’ Synagoge Oost, Linnaeus Street

There were few places where architecture’s competing forms of modernism overlapped more than the Netherlands in the 1920s. Traditionalists like Kropholler, De Stijl’s Oud, Rationalists like van der Vlugt and Duiker, and the versatile Dudok built alongside the work of the capital’s eponymous ‘Amsterdam school’ style.

The influence of the great Dutch architect Pierre Cuypers — Holland’s Pugin — might be inferred as the progenitors of the Amsterdam school (De Klerk, van der Mey, and Kramer) all studied or worked in the firm of Cuypers’ nephew Eduard.

The Dutch capital’s take on the brick expressionism originated among its Hanseatic neighbours but was sufficiently distinct to merit its own name. Architect Jacobus Baars (1886-1956) deployed the style to great effect in the work he did for Amsterdam’s then-flourishing Jewish community.

Baars designed the 1928 Synagoge Oost (East Synagogue) on Linnaeusstraat (Linnaeus Street) in the Transvaalbuurt neighbourhood that was developed in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Dutch sympathies in the then-still-recent Anglo-Boer War are obvious from the naming of local streets and squares (and, indeed, the district) after Afrikaner places, battles, and statesmen.

The architect placed the building at an angle so that the entrance could face on to Linnaeusstraat while the holy ark containing the Torah scrolls faced Jerusalem, skilfully filling in the rest of the site with clergy and school structures ancillary to the sanctuary and congregation. (more…)

Ödön von Horváth

When the shop purveying diacritical marks opened one morning in Vienna, in my mind the writer Ödön von Horváth turned up and said “Thanks. I’ll have the lot.”

It wasn’t even his real name, of course — which was Edmund Josef von Horváth. A child of the twentieth century, von Horváth was born in Fiume/Rijeka in 1901. His father was a Hungarian from Slavonia (in today’s Croatia) who entered the imperial diplomatic service of Austria-Hungary and was ennobled, earning his “von”.

“If you ask me what is my native land,” von Horváth said, “I answer: I was born in Fiume, grew up in Belgrade, Budapest, Preßburg, Vienna, and Munich, and I have a Hungarian passport.”

“But homeland? I know it not. I’m a typical Austro-Hungarian mixture: at once Magyar, Croatian, German, and Czech; my name is Hungarian, my mother tongue is German.”

From 1908 his primary education was in Budapest in the Hungarian language, until 1913 when he switched to instruction in German at schools in Preßburg (Bratislava) and Vienna.

Von Horváth went off to Munich for university studies — where he began writing in earnest — but quit midway through and moved to Berlin.

He once told his friends the story of when he was climbing in the Alps and stumbled upon the remains of a man long dead but with his knapsack intact.

Intrigued, he opened the knapsack and found an unsent postcard upon which the deceased had written “Having a wonderful time”.

“What did you do with it?” his friends naturally inquired. “I posted it!” was von Horváth’s reply.

In 1931 he was awarded the Kleist Prize for literature, but two years later the National Socialists took the helm and von Horváth thought it best to move across the border to his old imperial capital of Vienna.

Despite his anti-nationalism, he did initially join the guild for German writers set up by the Nazis, possibly to keep his works in print in the Reich while he was living in still-independent Austria.

It was in Vienna he published his best-known work: Jugend ohne Gott — “Youth without God” (first translated into English as The Age of the Fish), which marked his public point-of-no-return break with the Hitlerites.

The novel depicts a jaded schoolteacher increasingly disconnected from his profession and the world around him as the ideology of National Socialism begins to take root in the education system. (Bizarrely, it was also scantly used as the basis for a 2017 dystopian thriller.)

When Hitler’s troops marched into Austria the following year, von Horváth fled to Paris.

“I am not so afraid of the Nazis,” he told a friend there one day. “There are worse things one can be afraid of, namely things you are afraid of without knowing why. For instance, I am afraid of streets. Roads can be hostile to you, can destroy you. Streets frighten me.”

Days later, in the middle of a thunderstorm, von Horváth was walking down the Champs-Élysées — the most famous street in Paris — when a flash of lightning struck a tree, felled a branch, and struck the writer dead. He had been on his way to the cinema to see Walt Disney’s ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’.

Years ago someone recommended The Eternal Philistine: An Edifying Novel in Three Parts to me, but I have to admit I haven’t yet read it, or much else of von Horváth’s work. (He’s on my fiction wish-list though.)

His plays have been revived, too — here in London at the Almeida and the Southwark Playhouse in the past decade or so — and both The Eternal Philistine and Youth Without God are available in English from the estimable Neversink Library imprint of Melville House.

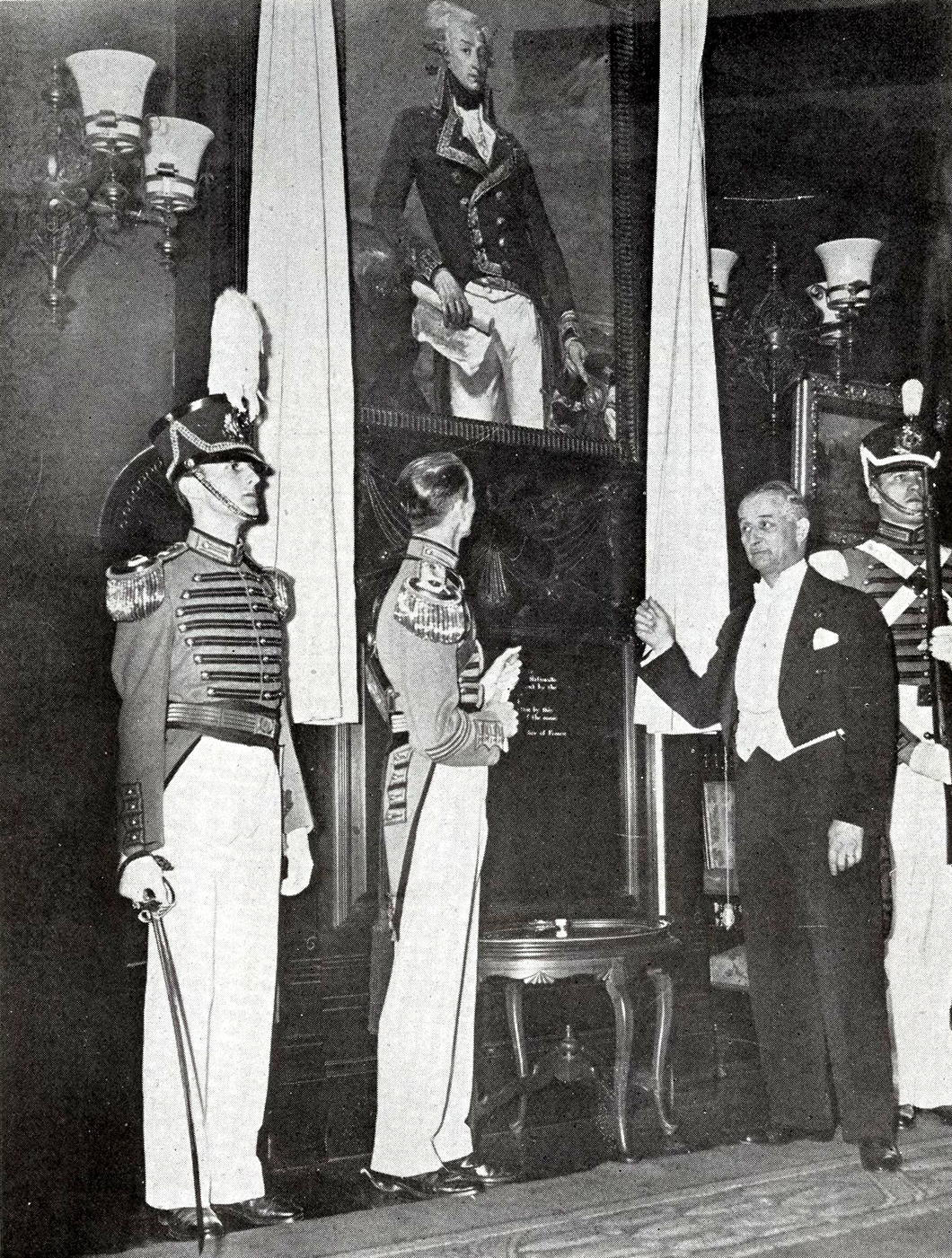

Lafayette at the Seventh

For the first century or so in the history of the United States, there was no more popular Frenchman in America than the Marquis de Lafayette. This nobleman of the Auvergne was an officer in the King’s Musketeers aged 14 and was purchased a captaincy in the Dragoons as a wedding present aged 18 in 1775. Within a year the rebel faction in North America had sent Silas Deane of Groton to Paris as an agent to negotiate support from the French sovereign, but Paris acted cautiously at first.

Lafayette — a young aristocratic freemason and liberal with a head full of Enlightenment ideas — escaped to America in secret and was commissioned a major-general on George Washington’s staff in the last of his teenage years.

Given his relative youth, Lafayette inevitably turned out to be the final survivor of the generals of the Continental Army, and his 1824 trip to the United States solidified his popularity. He visited each of the twenty-four states in the Union at the time, including New York where the predecessor of the Seventh Regiment named itself the National Guards in honour of the Garde nationale Lafayette commanded in France.

This was the first instance of an American militia unit taking the name National Guard, which in 1903 was extended to all of state militia units which could be called upon for federal service.

In honour of this connection and on the centenary of Lafayette’s 1834 death, the French Republic presented the Seventh Regiment with a copy of Joseph-Désiré Court’s portrait of the general that hangs in the 1792 Room of the Palace of Versailles. The Seventh set this in the wall of the Colonel’s Reception Room in their Armory, facing a copy of Peale’s portrait of General Washington.

The privilege of unveiling the portrait went to André Lefebvre de Laboulaye, the French Ambassador to the United States, who was given the honour of a full dress review of the Seventh Regiment on Friday 12 April 1935 before a crowd of three thousand in the Amory’s expansive massive drill hall.

Also present at the occasion was his son François, who eventually in 1977 stepped into his late father’s former role as French Ambassador to the United States. His Beirut-born grandson Stanislas served as French Ambassador to Russia 2006-2008 before being appointed to the Holy See until 2012. In April 2019, Stanislas de Laboulaye was put in charge of raising funds for the rebuilding of Notre-Dame following the fire that devastated the cathedral.

The Irishman at Yorktown

General Charles O’Hara and the Surrender of Lord Cornwallis

Today marks two-hundred-and-forty-one years since the British general Lord Cornwallis surrendered to a joint Rebel-French force at Yorktown in Virginia — perhaps the most embarrassing British defeat until the Fall of Singapore to the Japanese more than a century and a half later.

Every American schoolboy, or indeed any visitor to the United States Capitol, is familiar with John Trumbull’s oil painting of the scene at Yorktown.

Somewhat pitifully, Lord Cornwallis pled ill health and did not attend the formal ceremony of surrender.

Instead, he sent his adjutant to act on his behalf: a wily character by the name of General Charles O’Hara.

O’Hara had soldiering in his blood, being the illegitimate son of a Portuguese woman and Field Marshal the Rt Hon James O’Hara, 2nd Baron Tyrawley and 1st Baron Kilmaine. The elder O’Hara was the sometime envoy-extraordinary to the King of Portugal, where he made the acquaintance of the woman who bore him one of at least three of his sons-born-the-other-side-of-the-blanket.

Lord Tyrawley looked after his son, sending him to Westminster School before buying him an army commission and keeping him close by in the Coldstream Guards which the father commanded himself.

Young Charles was at one point sent on assignment to Senegal commanding a corps of African army convicts which, reading between the lines, may have been a punishing demotion.

He soon regained his command with the Guards though and was sent to America where the royal troops were fighting against a surprisingly cohesive force of rebel English colonists.

Despite being surrounded by numerous American loyalists, O’Hara tended to distrust the colonists and viewed them with suspicion, tarring them all with the brush of rebellion openly practiced only by a distinct (but ultimately successful) minority.

He was wounded at the Battle of Guildford Court House in March 1781, and by the Siege of Yorktown had been promoted to Cornwallis’s second-in-command. (more…)

Harlem Reformed Dutch Church

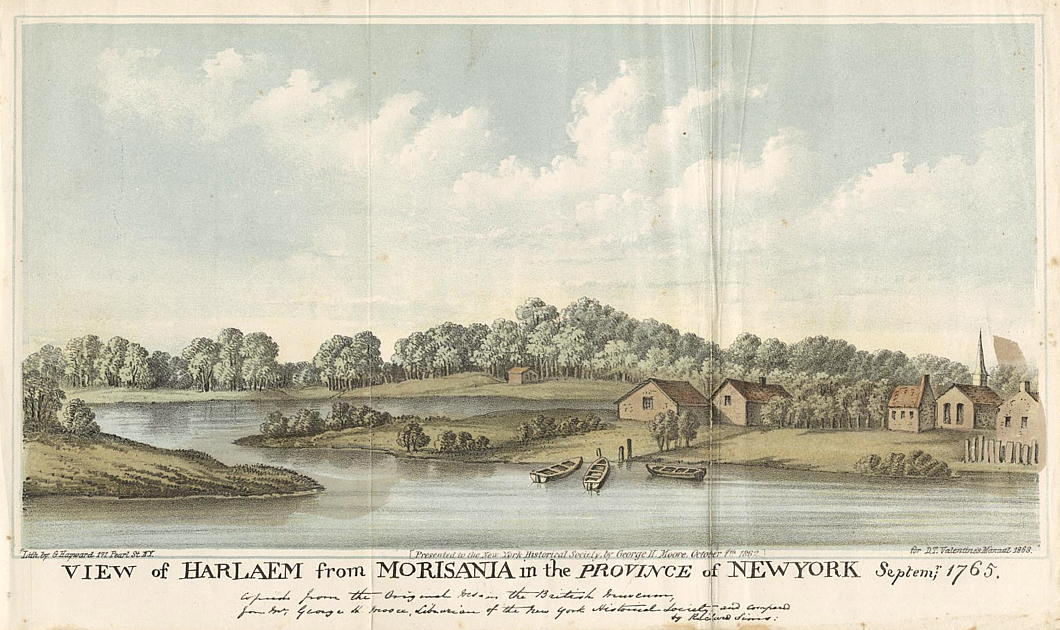

For much of Manhattan’s early colonial history, the island was home to two primary settlements: the port of New Amsterdam (later, from 1664, New York) way down at the southern tip and the town of Harlem up where the East River meets the Harlem River.

Christened after the Dutch city, Harlem is one of Manhattan’s most visible links to the Netherlands. The local newspaper is even called the New York Amsterdam News, once a prominent voice in Black America given this neighbourhood became predominantly African-American in the early twentieth century, and Amsterdam Avenue runs up as the spine of West Harlem.

Harlem was founded in 1658, thirty-four years after New Amsterdam was founded and thirty-two since Peter Minuit bought the whole island of Mannahatta off the Indians for sixty guilders.

The town’s first church was founded in 1660 but didn’t have its own dedicated building for a few years. The Harlem Reformed Dutch Church, or Collegiate Church of Harlem, was built in 1665-67 right on the banks of the Harlem River, around the site of East 127th Street and First Avenue today.

Both the building and site was abandoned twenty years later when the congregation moved to its second building, completed 1687, just a little bit further south — near where East 125th meets First Avenue, or where the entrance ramp to the Triborough Bridge meets 125th.

It is this second building, which is depicted in the view above of Harlem village from Morissania across the river in the Bronx in 1765 (below).

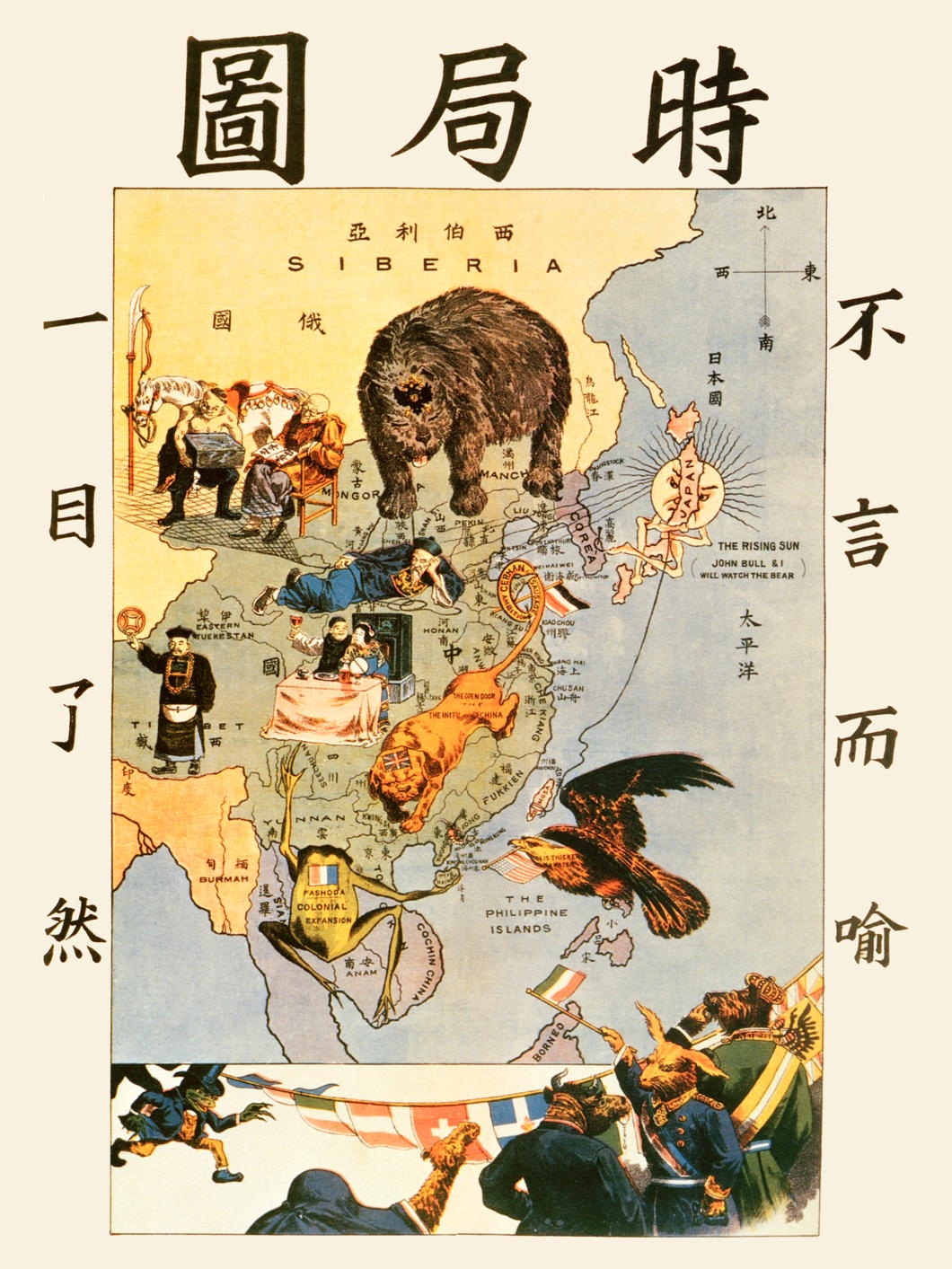

The Situation in the Far East

A century-old geopolitical cartoon is updated for today

Tse Tsan-tai — or 謝纘泰 if you fancy — was by any standard a remarkable man. Born in New South Wales, this Chinese-Australian Christian was a colonial bureaucrat, nationalist revolutionary, constitutional monarchist, pioneer of airship theory, and co-founded the South China Morning Post — still one of the most prominent newspapers in the Orient.

Tse’s most important visual contribution was a widely distributed political cartoon usually known in English as ‘The Situation in the Far East’ or in Chinese as the ‘Picture of Current Times’ (below).

Crafted as a propaganda measure to warn his fellow Chinese of the designs of foreign powers, the cartoon depicts the perils facing the Middle Kingdom.

Japan, with its expanding navy, proclaims it will watch the seas with its ally, Great Britain. The Russian bear looms from Siberia, crossing the border into China. A British lion sprawls over the land, its tail tied up by the “German Sausage Ambitions” at Tsingtao. The French frog guards Indochina while the American eagle lurks from the Philippines.

Meanwhile, the Chinese figures show sleeping bureaucrats and carousing intelligentsia unresponsive to the external threats.

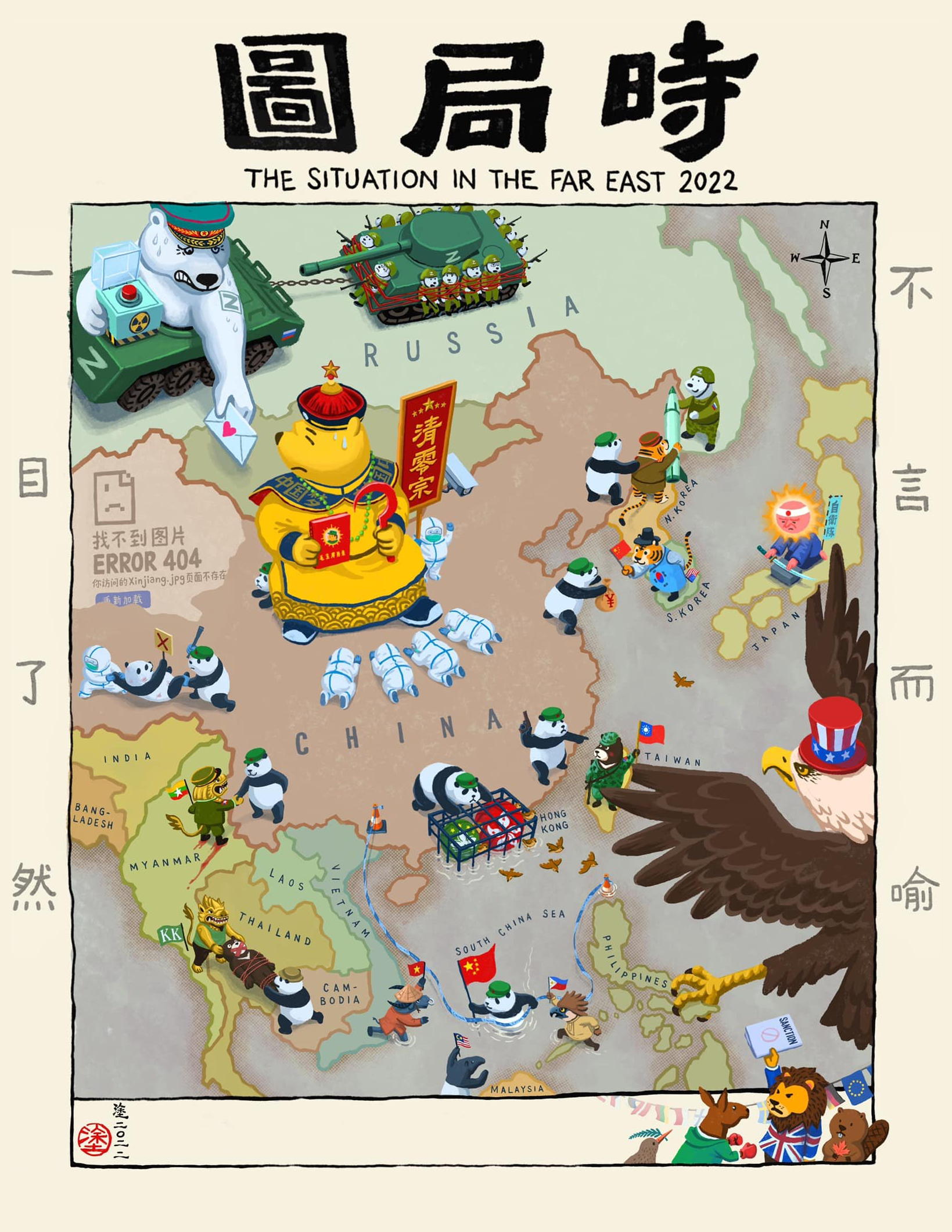

Now the exiled Hong Kong artist Ah To (阿塗) has updated ‘Situation’ to reflect the realities of 2022. (more…)

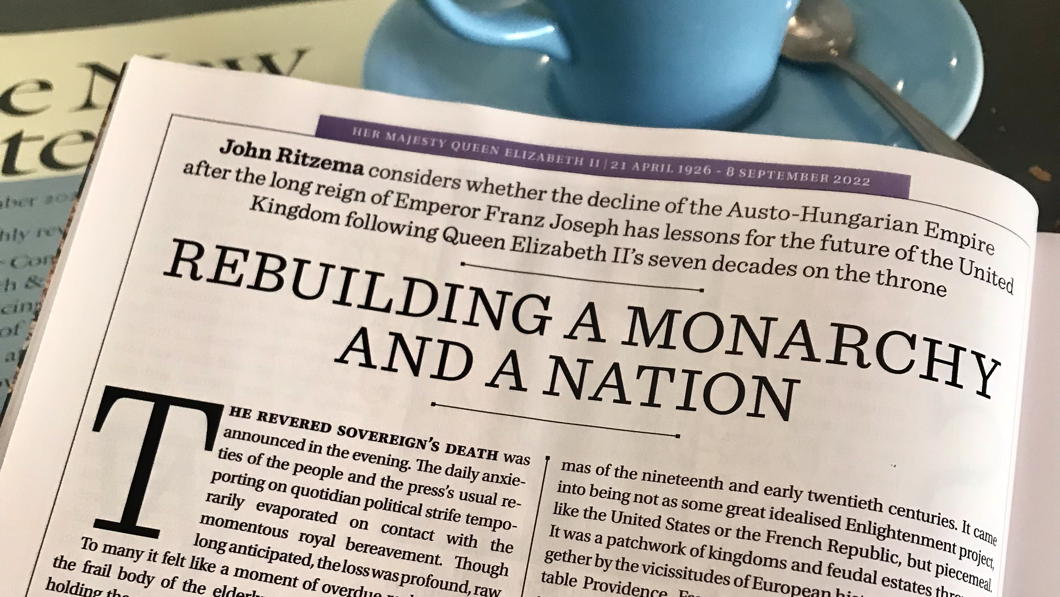

The death of The Monarch

The revered Sovereign’s death was announced in the evening. The daily anxieties of the people and the press’s usual reporting on quotidian political strife temporarily evaporated on contact with the momentous royal bereavement. Though long anticipated, the loss was profound, raw.

To many it felt like a moment of overdue reckoning. As if the frail body of the elderly monarch had somehow been holding the great, ancient, long-weakening and precariously multinational state together. The world of the previous century had finally, almost imperceptibly, slipped away. Franz Joseph was dead. …

In the October 2022 number of The Critic, Dr John Ritzema explores the parallels between the recent demise of our late sovereign with the death of the Emperor Franz Joseph over a hundred years earlier — and wonders whether there are any lessons for the reign of King Charles III: Rebuilding a Monarchy and a Nation.

One of those minor curiosities that both Franz Joseph and Elizabeth II were succeeded by Charleses — the latter by her son, and the former by his grand-nephew Blessed Charles of Austria.

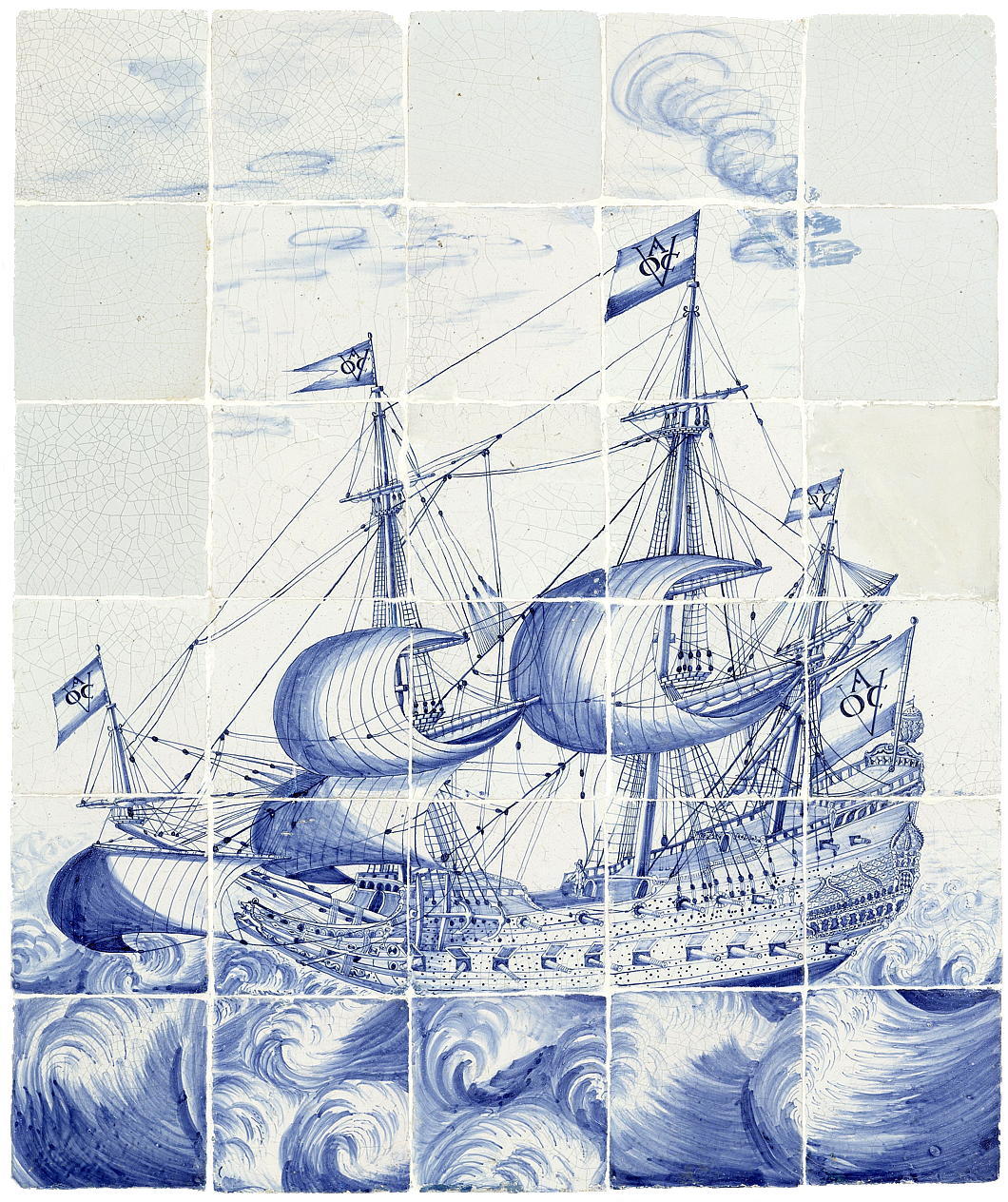

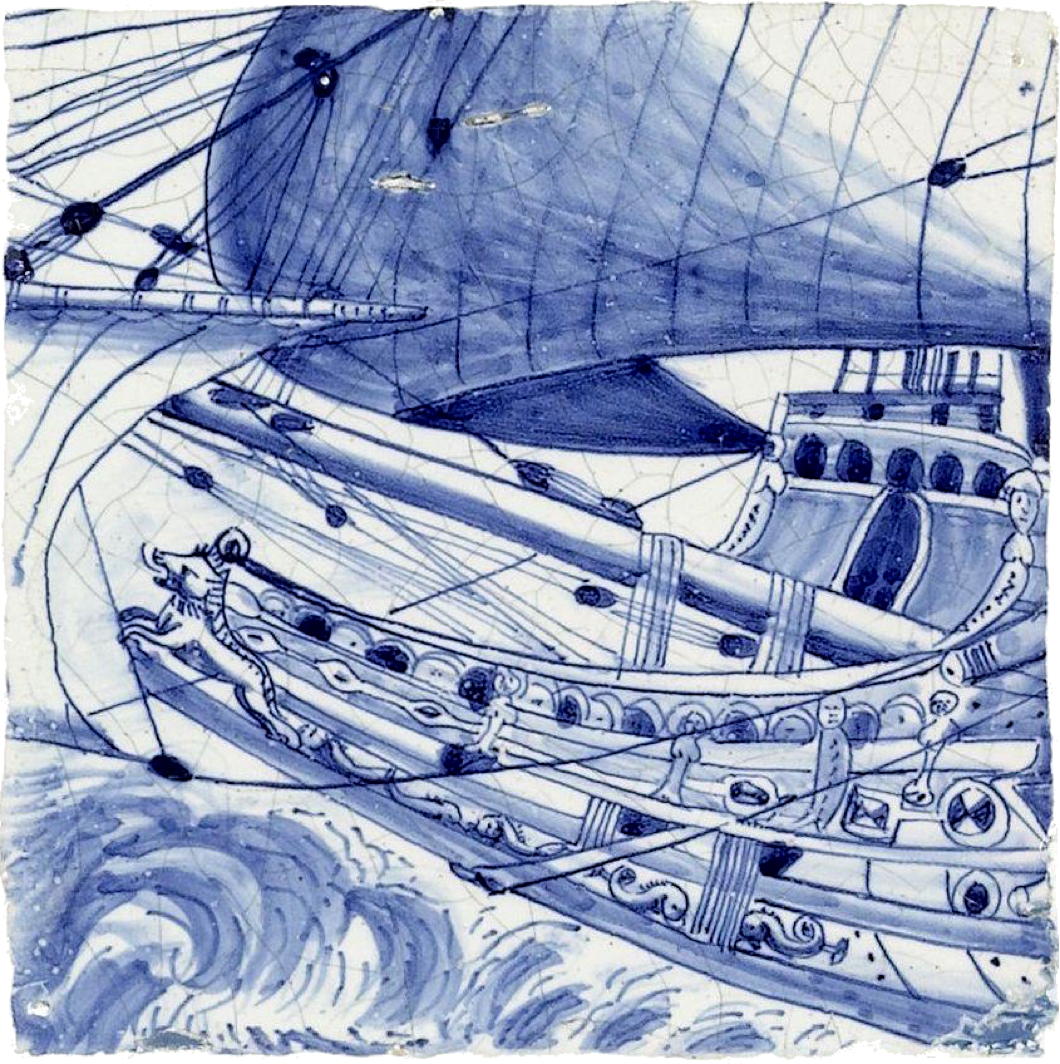

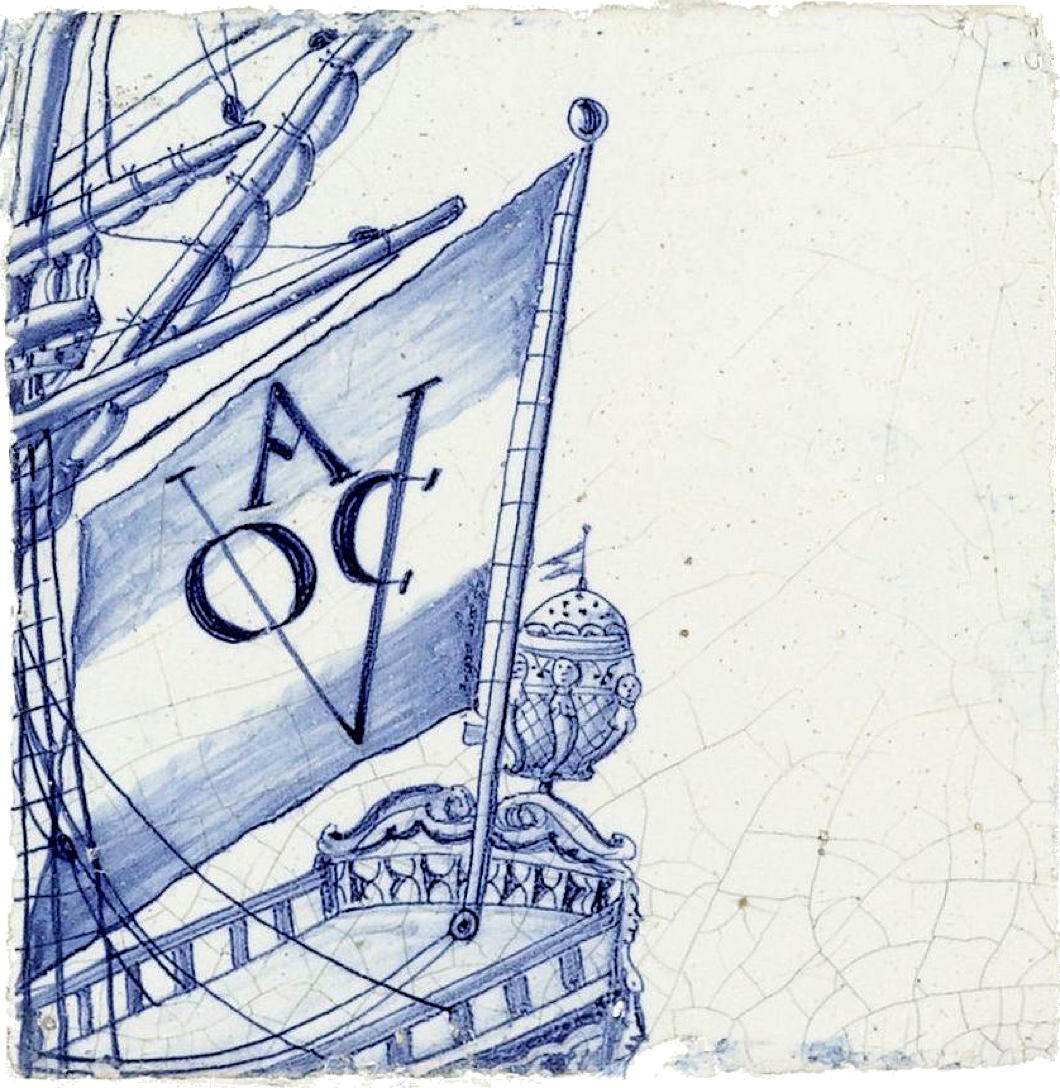

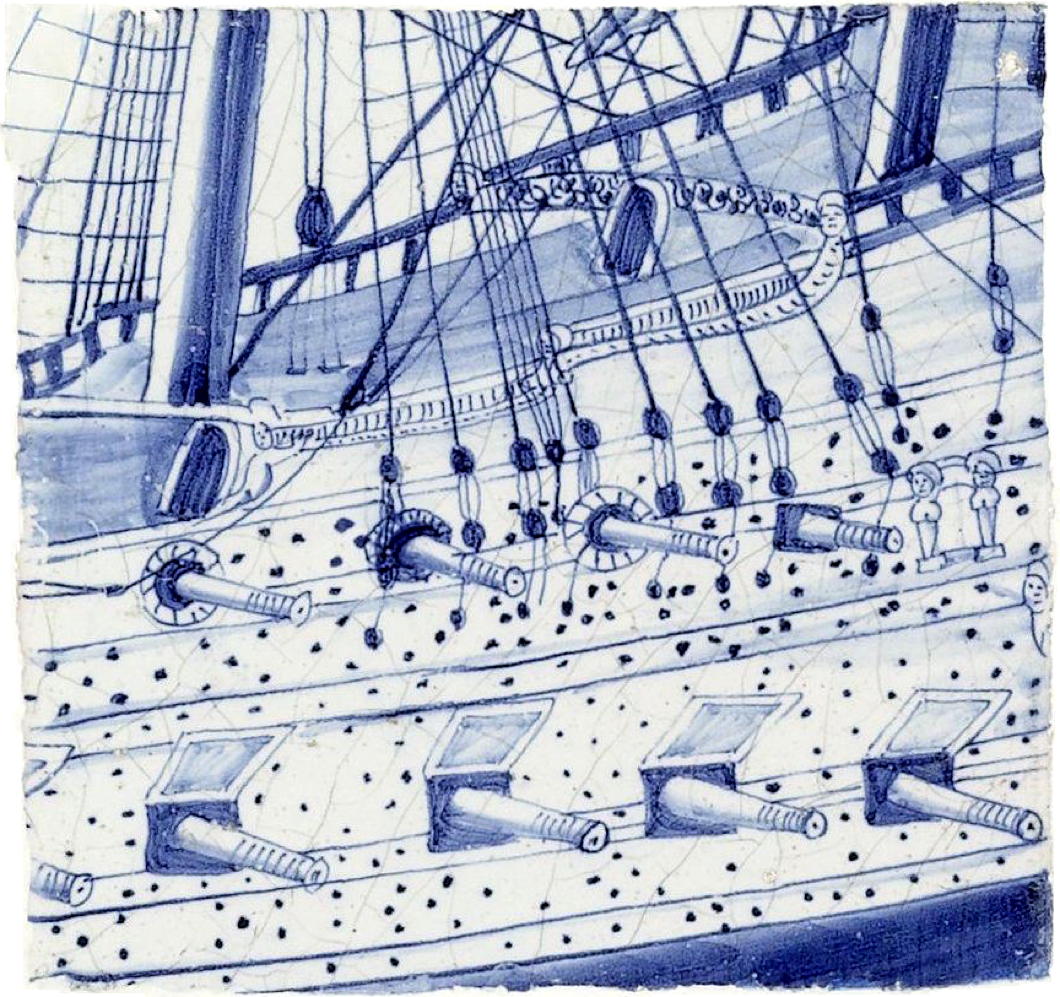

An East Indiaman

English sea-goers and merchants commonly referred to any ship of the Dutch VOC (or of other similar companies) as an ‘East Indiaman’.

Cypher Shift

Out with the old, in with the new: the King has released his new royal cypher, with a stylised CR III replacing the familiar EIIR. As with so many things, I am sure we will get used to it with time.

Given the longevity of the late Queen’s reign it will be some time before we see it appearing on pillarboxes, but it will enter our lives more quickly via postal franking, stamps, currency, and uniforms.

Many are trying to come up with complex, almost mystical, explanations for why St Edward’s Crown has been replaced with the Tudor crown atop the cypher. More likely, I suspect, is that it is a useful means of giving the new reign a respectful visual differentiation from its preceding one.

I’ve always been rather fond of the Tudor crown, and the Caledonian version of the new cypher rightly includes the Crown of Scotland — the oldest amidst the Crown Jewels of this realm as (unlike England) Scotland was spared the iconoclastic destruction of Cromwell’s republic.

The new royal cypher, left, and its Scottish variant, right.

Elizabeth II

ELIZABETH II

the United Kingdom

of Great Britain & Northern Ireland

Canada

Australia

New Zealand

Jamaica

the Bahamas

Grenada

Papua New Guinea

the Solomon Islands

Tuvalu

Saint Lucia

Saint Vincent & the Grenadines

Antigua & Barbuda

Belize

and Saint Kitts & Nevis

quondam Queen of South Africa, Pakistan, Ceylon, Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Tanganyika, Trinidad & Tobago, Uganda, Kenya, Malawi, Malta, the Gambia, Guyana, Barbados, Mauritius, and Fiji

Head of the Commonwealth

Defender of the Faith

Duke of Normandy

Duke of Lancaster

Lord of Mann

Head of the House of Windsor

The Accident of Birth

A king is a king, not because he is rich and powerful, not because he is a successful politician, not because he belongs to a particular creed or to a national group. He is king because he is born.

And in choosing to leave the selection of their head of state to this most common denominator in the world — the accident of birth — Canadians implicitly proclaim their faith in human equality, their hope for the triumph of nature over political manoeuvre, over social and financial interest; for the victory of the human person.

— Fr Jacques Monet SJ FRSC

St George’s Basilica, Prague Castle

Monolingual Limitations

I’m  sure I wasn’t the only twelve-year-old whose favourite book was Edward Luttwak’s delicious Coup d’État: A Practical Handbook — an excellent gift from my father. The work gave me a lifelong fascination with the golpe de Estado, a phenomenon of government all too increasingly a rare species in our post-Cold War era.

sure I wasn’t the only twelve-year-old whose favourite book was Edward Luttwak’s delicious Coup d’État: A Practical Handbook — an excellent gift from my father. The work gave me a lifelong fascination with the golpe de Estado, a phenomenon of government all too increasingly a rare species in our post-Cold War era.

Just about everything written or said by Luttwak — lately a cattle farmer in Paraguay — is worth reading or listening to. For a start you could read his contributions to the LRB or to the excellent American Jewish Tablet magazine.

I have been waiting for someone to offer a refutation of his provocative Prospect essay on how the Middle East is less relevant than ever, and it would be better for everyone if the rest of the world learned to ignore it.

David Samuels chat with Luttwak this month on the subject of the Three Blind Kings — Putin, Biden, and Xi — offers some superb insights as well as amusements.

Among the lessons that Luttwak is keen to drive home — and he says so over and over and over again on Twitter — is that American intelligence-gathering (and government in general) is too reliant on technology with too few officials, analysts, and operatives actually learning the language of those they are attempting to surveil.

That this state of monolingual limitation was not always the case was driven home in an excellent piece by Jonathan Gaisman in the February 2022 New Criterion concerning Sir Ronald Storrs (left, 1881–1955) — “the most brilliant Englishman in the Near East” as Lawrence of Arabia called him.

That this state of monolingual limitation was not always the case was driven home in an excellent piece by Jonathan Gaisman in the February 2022 New Criterion concerning Sir Ronald Storrs (left, 1881–1955) — “the most brilliant Englishman in the Near East” as Lawrence of Arabia called him.

An accomplished Arabist, Storrs served as Oriental Secretary for the British administration in Egypt before going on to become Military Governor of Jerusalem, Governor of Cyprus, and Governor of Northern Rhodesia, from which role he retired on health grounds, returned to the metropole, and served a few years on London County Council.

Gaisman relays this delicious anecdote from the British official’s 1937 autobiography Orientations:

Sometime in 1906 I was walking in the heat of the day through the Bazaars. As I passed an Arab café an idle wit, in no hostility to my straw hat but desiring to shine before his friends, called out in Arabic, “God curse your father, O Englishman.”

I was young then and quicker-tempered, and foolishly could not refrain from answering in his own language that I would also curse his father if he were in a position to inform me which of his mother’s two and ninety admirers his father had been.

I heard footsteps behind me and slightly picked up the pace, angry with myself for committing the sin [of] a row with Egyptians. In a few seconds I felt a hand on each arm. “My brother,” said the original humorist, “return, I pray you, and drink with us coffee and smoke. I did not think that Your Worship knew Arabic, still less the correct Arabic abuse, and we would fain benefit further by your important thoughts.”

Gaisman further spoils us with another excellent story — this time about Storrs’ predecessor as Oriental Secretary in Cairo, Mr Harry Boyle:

[Boyle] was taking his tea one day on the terrace of Shepheard’s Hotel when he heard himself accosted by a total stranger: “Sir, are you the Hotel pimp?”

“I am, Sir,” Boyle replied without hesitation or emotion, “but the management, as you may observe, are good enough to allow me the hour of five to six as a tea interval. If, however, you are pressed perhaps you will address yourself to that gentleman,” and he indicated [the self-made tea magnate] Sir Thomas Lipton, “who is taking my duty; you will find him most willing to accommodate you in any little commissions of a confidential character which you may see fit to entrust to him.”

Boyle then paid his bill, and stepped into a cab unobtrusively, but not too quickly to hear the sound of a fracas, the impact of a fist and the thud of a ponderous body on the marble floor.

Boyle’s 1937 obituary in the Palestine Post noted he was “a gifted linguist, speaking no fewer than twelve languages”. When Lord Cromer was Britain’s proconsul in Egypt, he and Boyle were such frequent perambulators along the Nile that Boyle earned the nickname Enoch, for he “walked daily with the Lord”.

Boyle’s 1937 obituary in the Palestine Post noted he was “a gifted linguist, speaking no fewer than twelve languages”. When Lord Cromer was Britain’s proconsul in Egypt, he and Boyle were such frequent perambulators along the Nile that Boyle earned the nickname Enoch, for he “walked daily with the Lord”.

During these walks, Cromer was keen to mix with Egyptians of the most humble backgrounds and was aided by Boyle’s linguistic skills. Such was his excellence in Arabic that, returning to Egypt many years later, Boyle was recognised by a peasant farmer many miles outside of Cairo and warmly embraced as the man who used to walk the Nile with the British lord.

“In the hot and brooding nights of the Egyptian summer,” the Post appreciation also relates, “when all who were at liberty to do so had fled to cooler climes, Cromer and Harry Boyle might often have been seen seated after dinner on the veranda of the Agency in Cairo reading aloud alternately passages from the Iliad.”

Perhaps all is not lost. While I can’t speak for the state of the gift of tongues at Langley, at least the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom can launch into Homer, in Greek, from memory.

But Luttwak would surely be right to retort that it is among the mid-level officials and analysts that linguistic skills are most missing — nor are we currently threatened by Athens, Sparta, or Corinth.

30 mai 1968

The events of May 1968 have been fetishised by the romantic radical left but ended in the triumph of the popular democratic right. Battered by two world wars, France had enjoyed an unprecedented rise in living standards since 1945 — especially among the poorest and most hard-working — and a new generation untouched by the horrors of war and occupation had risen to adulthood (in age if not in maturity). The ranks of the middle class swelled as more and more people enjoyed the material benefits of an increasingly consumerised society, while those left behind shared the same aspirations of moving on up.

Like any decadent bourgeois cause, the spark of the May events was neither high principle nor addressing deep injustice but rather more base impulses: male university students at Nanterre were upset they were restricted from visiting female dormitories (and that female students were restricted from visiting theirs). The ensuing events involved utopian manifestos, barricades in the streets, workers taking over their factories, a day-long general strike and several longer walkouts across the country.

The French love nothing more than a good scrap, especially when it’s their fellow Frenchmen they’re fighting against. Working-class police beat up middle-class radicals but for much of the month both sides made sure to finish in time for participants on either side to make it home before the Métro shut for the evening. But workers’ strikes meant everyday life was being disrupted, not just the studies of university students. When concessions from Prime Minister Georges Pompidou failed to calm the situation there were fears that the far-left might attempt a violent overthrow of the state.

De Gaulle himself, having left most affairs in Pompidou’s hands, finally came down from his parnassian heights to take charge but then suddenly disappeared: the government was unaware of the head of state’s location for several tense hours.

It turned out the General had flown to the French army in Germany, ostensibly to seek reassurance that it would back the Fifth Republic if called upon to defend the constitution. De Gaulle is said to have greeted General Massu, commander of the French forces in West Germany, “So, Massu — still an asshole?” “Oui, mon général,” Massu replied. “Still an asshole, still a Gaullist.”

The morning of 30 May 1968, the unions led hundreds of thousands of workers through the streets of Paris chanting “Adieu, de Gaulle!” The police kept calm, but the capital was tense and there was a sense that things were getting out of hand. Pompidou convinced de Gaulle the Republic needed to assert itself.

Threatened by a radicalised minority, de Gaulle called upon the confidence of the ordinary people of France. At 4:30 he spoke on the radio briefly, announcing that he was calling for fresh elections to parliament and asserting he was staying put and that “the Republic will not abdicate”.

Before the General even spoke some his supporters (organised by the ever-capable Jacques Foccart) were already on the avenues but the short four-minute broadcast inspired teeming masses onto the streets of central Paris, marching down the Champs-Élysées in support of de Gaulle.

US Army Chief in London

General James C. McConville, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, dropped into London this week to meet with General Sir Patrick Sanders, who will take over as his British opposite number (Chief of the General Staff) later this year.

Both are the head of their countries’ respective armies and subordinate to overall defence chiefs, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the US and the Chief of the Defence Staff here in the United Kingdom.

General McConville was welcomed to the official Army Headquarters at Horse Guards, Whitehall, by the Major General Commanding the Household Division, Maj. Gen. Chris Ghika.

A contingent from the Coldstream Guards and the Band of the Irish Guards put together a ceremonial display and Gen. McConville took the salute.

Gen. McConville will also deliver the Kermit Roosevelt Lecture at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst this week.

The general’s visit provided a chance to show off the US Army’s new service uniform — modelled on the popular old pinks and greens.

This provides a much welcome alternative to the Dress Blues which, to my mind, make soldiers look like glorified policemen.

As I wrote when discussing similar changes in Peru, it’s not turning the clock back: it’s choosing a better future.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories