Tradition

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The BBC: Can’t they get anything right?

His Imperial Majesty, Haile Selassie I was the Emperor of Ethiopia up to his death at the hands of Communist revolutionaries, so it seems a bit silly to call him the “former Ethiopian Emperor”. More importantly, however, is that he was a devout Christian and was so opposed to Rastafarianism, which considered Haile Selassie to be the Messiah, that he sent Orthodox missionaries to Jamaica in order to convert Rastafarians to Christianity.

New York Needs a Monarchy

In the business section of today’s New York Sun, of all places, Liz Peek gives us another reason why we need a monarchy. In ‘Why America Needs Its Own Queen’s Award‘, Ms. Peek profiles the Queen’s Award for Enterprise, initiated by Royal Warrant in 1966 as the Queen’s Award for Industry and awarded to British companies for excellence in international trade, innovation, and sustainable development.

In the business section of today’s New York Sun, of all places, Liz Peek gives us another reason why we need a monarchy. In ‘Why America Needs Its Own Queen’s Award‘, Ms. Peek profiles the Queen’s Award for Enterprise, initiated by Royal Warrant in 1966 as the Queen’s Award for Industry and awarded to British companies for excellence in international trade, innovation, and sustainable development.

Of course, Ms. Peek attempts to offer some possible solutions to our detrimental lack of monarchy with regard to this particular aspect, but none of them have quite the appeal of restoring the monarchy. All that would really be necessary would be to pass an amendment removing fourteen words from Article IV, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution. This is the part that requires the member states of the United States to have republican forms of government. This removal would at least give states the option of becoming monarchies, which is only fair, after all.

Category: Monarchy

A Happy Birthday to Her Majesty

In honour of the anniversary of the birth of Her Majesty Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, I raised a glass of Warre’s (Purveyors to the Household of the Queen of Denmark) this evening. May God bless and keep Her Majesty!

Some of you may recall that Her Majesty is of a somewhat artistic temperment. She sent her sketches inspired by The Lord of the Rings to J.R.R. Tolkein while he was alive, and the author liked them so much he had them published in the Danish edition of the trilogy. Above is an episcopal cope designed by Her Majesty in 1988 for the Cathedral of Viborg.

His Royal Highness Prince Christian, the Queen’s grandson and the future King of Denmark.

Naturally, we also wish a very happy birthday and many, many bountiful blessings to another of Christendom’s reigning monarchs: Christ’s vicar and our Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI, who, it seems, is a reader of Chronicles. God bless our Pope, the great, the good!

The Tragedy of the Falklands War

An article (two versions of which are reproduced here below) recently printed exemplifies one of the tragic aspects of the Falklands War: the Anglo-Argentines who, out of loyalty to their homeland, were forced into waging war against their mother country. The subject of the article, Mr. Alan Craig, happens to be a former student of St. Alban’s College, a fine institution in the Provincia de Buenos Aires (currently celebrating its centenary) which I had the great privilege of briefly attending. (C.f. How Andrew Cusack Became a Tea Drinker). Another sad aspect of the Falklands War is that if there are any two nations which should enjoy the bonds of friendship, it is Britain and Argentina. It is a shame when two countries which should be natural companions, perhaps allies, have deep-seated and long-lasting emotions in the way. (One thinks of Germany and Poland in particular).

Interestingly, Argentine textbooks contain maps of the Falkland Islands in which all the towns and geographical features have contrived names en Castellano. Port Stanley, for example, is called Puerto Argentino, while the Falklands themselves are known to Argentines as las Malvinas.

I remember one day in geography class at St. Alban’s, exhibiting the typical brash arrogance of a youthful Anglo-Saxon, raising my hand, being called on by the teacher, and pronouncing “Sir, I have studied geography all my life, and I spend a lot of time reading maps. I don’t believe there exists such a place called ‘the Malvinas’ though the Falklands…”. I was going to continue that the Falklands “are roughly the shame shape and size and in the same place as this map depicts” (or something to that effect) but I had been interrupted by such a hail of paper, pens, and whatever moveable objects my fellow students could get their hands on (I think Nico, that Russian bastard, had actually thrown a book) that I found it more prudent to take cover underneath my desk rather than continue upon the particular oratorical course upon which I had embarked.

Nonetheless, we pray eternal rest to all the soldiers who fell on those windy isles a quarter-century ago, and that those who survived will live in the peace which their sacrifice has earned for them.

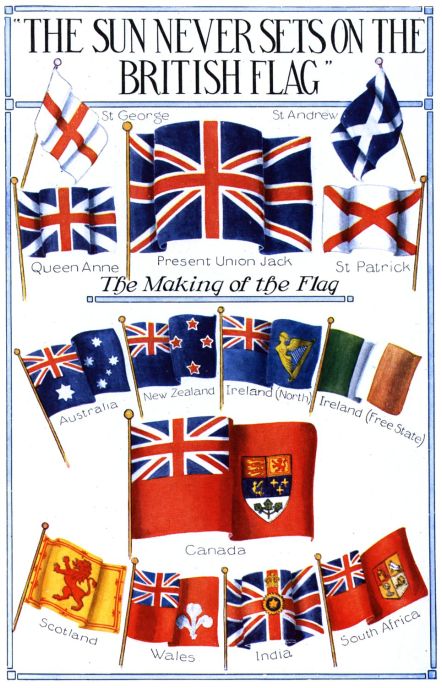

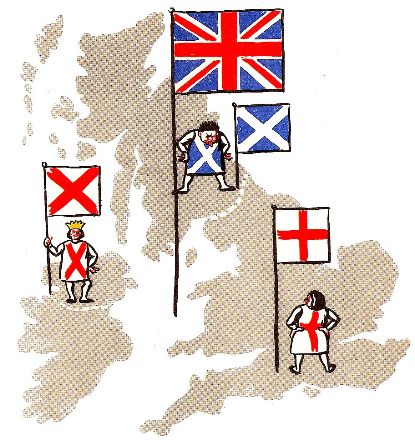

Flags of the British Nations

It is interesting how little-valued accuracy was in the depiction of flags “back in the day”. In this illustration, for example, the flags of Wales and “Ireland (North)” are mere inventions while the Scottish and Indian ones are arguable yet imprecise.

The “Welsh” flag depicted is a red ensign that is defaced with the three feathers of the Prince of Wales.

The “Ireland (North)” flag is handsome, but nonexistent. Northern Ireland had an official flag in use from 1953 until the Parliament of Northern Ireland was prorogued in 1972. (It was never recalled, and has since been superseded by the Northern Ireland Assembly). The flag of “Norn Iron” was a banner of the province’s coat of arms.

The flag of Scotland shown here is not actually the national flag (depicted above as the “St. Andrew” flag) but rather the Scottish royal standard, which is often (and improperly) used as an alternative national flag.

The Indian flag depicted is actually the flag of the Viceroy of India, which (admittedly) was sometimes used as a national flag for India. More often, however, a blue or red ensign was used, defaced with the Star of India.

The Canadian flag depicted here was changed in 1957, when the arms of Canada were themselves changed. The maple leaves in the bottom compartment of the sheild were specified to be “gules” (red). Up to that point, they had previously almost always been rendered “vert” (green). The Canadian flag itself was very controversially and unpopularly replaced by Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson with the Maple Leaf Flag. The Leader of the Opposition, the Rt. Hon. John Diefenbaker, derided the Liberal premier’s decision:

“We have had a flag. Flags can be changed. But flags cannot be imposed — the sacred symbols of a people’s hopes and aspirations — by the simple capricious personal choice of a prime minister of Canada. Now then, whenever the overwhelming majority of Canadian people want a new version, and when the design is meaningful and acceptable to most Canadians, that’s democracy. … I asked him [Prime Minister Pearson] this question: as to whether or not, under the circumstance, he would permit or he would arrange for a national referendum and his answer was no.”

Hail Glorious Saint Patrick

THE FEAST OF IRELAND’S patron saint is an occasion for parading if ever there was one. For this, we can send part of our thanks to the British Army, which happened to initiate the most famous St. Patrick’s Day Parade of them all, namely, New York’s. It was 1762 when a number of Irish troops in the service of the Crown took it upon themselves to parade up Gotham’s own Broadway on the 17th of March. (More recently, the Duke of Edinburgh was invited to partake in the New York parade during his 1966 visit to America). Despite the lamentable outbreak of separatist republicanism in much of Ireland, the sons of Erin continue to take the Queen’s shilling and serve proudly in Her Majesty’s forces, and true to form they are sure to mark their patron’s feast day.

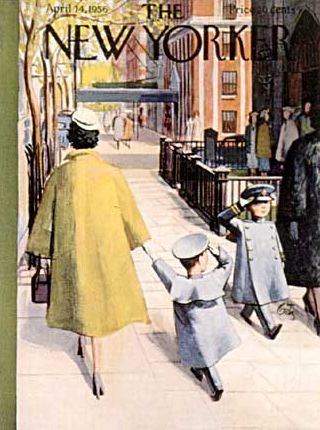

The Knickerbocker Greys

The Knickerbocker Greys, the Upper East Side corps of cadets, is celebrating its 125th year in existence. Both the Times and the Sun have featured articles on the Greys:

‘Celebrating 125 With the Knickerbocker Greys‘ by Gary Shapiro (The New York Sun)

‘Manhattan’s Littlest Soldiers‘ by Eric Königsberg (The New York Times)

Above: A mother mends a cadet’s uniform.

Below: Cadets assembled in an Armory corridor. (Note the interior scaffolding due to the State’s grievous neglect of the Armory).

Lord Glenavy

Sir James Henry Mussen Campbell, Bt., 1st Baron Glenavy, PC, QC. was born in Dublin in 1851. Campbell graduated from the University of Dublin (Trinity College) a Bachelor of the Arts in 1874. He was called to the Irish bar in 1878, being made a Queen’s Counsel in 1892.

Campbell was elected to Parliament in 1898, being called to the English bar a year later. He was made Solicitor General for Ireland in 1903, as well as being appointed an Irish Privy Counsellor. He rose to become Lord Chief Justice of Ireland in 1916, being made a baronet the following year, and Lord Chancellor of Ireland the year after that (1918). Sir James was ennobled as 1st Baron Glenavy upon relinquishing office in 1921.

Ireland was partitioned in the following year, and Lord Glenavy became the first Cathaoirleach of Seanad Éireann (Presiding officer of the Irish senate). In 1923, he chaired the judicial committee investigating the establishment of a new courts system for the Irish Free State. His proposals were implemented the following year in the Courts of Justice Act 1924, forming the Irish courts as they remain today.

Having served one six-year term in the Seanad, he did not seek re-election in 1928, and died three years later in 1931. Holding the largely honorary position of President of the College Historical Society (“the Hist”), Dublin University’s debating society, from 1925, he was succeeded upon his death by his fellow Irish Protestant, Douglas Hyde, who himself later became the first President of Ireland from 1938 until 1945.

The Men Who Saved Quebec

The British Crown’s toleration of Catholicism in Quebec was cited by the rebel colonists of the 1770’s as, ironically, an ‘intolerable act’. That the Church of Rome, that bastion of backwards conservatism and slavish hierarchy, could be tolerated in the lands under the power of the British parliament riled the Whigs—the enlightened liberal progressives of the day. Indeed, Benjamin Franklin was even so foolish as to go to Quebec as an emissary of the ‘Continental Congress’ to persuade the natives to rebel against the Crown; Congress’s proposals to ban Catholicism and prohibit the use of the French language ensured he was not successful.

The modern orthodox opinion of historians on the Quebec Act of 1774—the act that granted toleration to the Church—is that it was merely a persuasive exercise to keep les Canadiens from rebelling. A 1989 book challenged this perspective, arguing instead that a handful of British aristocrats were determined to ensure that Quebec did not become another Ireland: where Protestant ascendancy was thrust upon an unwilling nation of Catholic nobles, merchants, and peasants.

The following review by Gary Caldwell was published in a Canadian journal in 2001.

|

Philip Lawson.

The Imperial Challenge: Quebec and Britain in the Age of the American Revolution. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. 192 pages. US$27.95. |

WHY REVIEW A BOOK published twelve years ago? I will explain. But first, let me tell you what it’s about.

When Britain took possession of Canada at the Treaty of Versailles in 1763, it faced an “imperial challenge:” how to integrate into the empire a society fundamentally different from England – in language, religion, and legal and political institutions. At the time, England was vigorously intolerant of Roman Catholicism or “popery,” the religion of its major enemies, France and Spain. British Protestantism was closely tied to the dominant Whig political ideology born of the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89. This doctrinal legacy prescribed that all British subjects were possessed of very definite and equal liberties, liberties endowed upon and limited to those who conformed to the Whig-Protestant definition of being British.

Hence the problem of 1763. English law and constitutional practice allowed only for protestant public officials and elected representatives. This meant excluding the entire French-speaking population, some 70,000 to 80,000 (the “new subjects”) as compared to some 300 Protestants established in the colony (the “old subjects”).

There were two schools of thought as to what should be done. The Whig position, favoured by much of the English political leadership and commercial class on both sides of the Atlantic, was not to accommodate the new subjects. It amounted to an attempted destruction of the local culture and to exclusion of the French-speaking population from all juridical, political and social positions, the hoped-for consequence being assimilation in one, perhaps two, generations. In short, what had been imposed in Ireland with the “protestant ascendancy.”

The opposing school of thought, still marginal in 1763, believed such a policy both impracticable and undesirable. James Murray, Lord Shelburne, Lord Dorchester (Gary Carleton), H. T. Cramahe, Alexander Wedderburn, Lord Mansfield and William Knox not only held that a Protestant ascendancy in Quebec would ruin the colony, they also believed that Quebec society was deserving of being preserved. Murray and Dorchester, who knew Quebec and its people, were adamant: the Canadians were a good “race”—in Murray’s words, “perhaps the best and bravest race on the globe” (p. 48)—and if protected they and their society would flourish and be loyal to the Crown. As it happened, all of these administrators and Crown legal officers, with the exception of Cramahe, were Anglo-Irish or Scottish; not one of them was of English origin.

But how were the Canadians and their culture to be accommodated? There were, as Lawson demonstrates, three distinct dimensions to this accommodation. The first was to respect the prevailing legal code and custom in civil and property matters; the second, to refrain from putting into place an English representative assembly because it would be the instrument of the 300 or so English and American voters in the colony. By far the most important was the third dimension, tolerance in Quebec of Roman Catholicism, which meant the nomination of a Bishop, the tithe and the right of Catholics to hold public office. Dorchester and the others successfully won these concessions in London by 1770, and they were contained in the Quebec Act in 1774, to the horror of much of English public sentiment, and especially the Americans who were more resolutely against “popery” and more Whig than the English themselves.

When Benjamin Franklin arrived in Montreal in 1775 with the invading army of the Continental Congress, he carried secret orders to ban the popish religion and the French language. Fortunately, the Americans were stopped in Quebec by no other than Dorchester, back from getting the Quebec Act through Parliament. At the head of an army of old and new subjects he broke the 1775-76 siege of Quebec.

Lawson’s interpretation is insightful in putting the events into the context of the Irish question. The major players in promoting the accommodation that became the Quebec Act had in mind “the Irish Imbroglio,” and were determined not to repeat the error of the “protestant ascendancy” in Ireland. The Quebec Act emerges clearly as the culmination of thoughtful and courageous policy formulation, a model of generous statesmanship. Hence, as Lawson goes on to argue, the “toleration” of Roman Catholicism in the Quebec Act paved the way for the British Acts of Toleration of 1778.

Lawson also helps understand why Murray, Dorchester and the others came to the conclusions they did about the Canathan problem. These men were essentially empirical conservatives who found the answer “in the past”—Quebec society as they had known it in the 1760s—and the “elastic nature of the British Constitution.” And here Lawson runs smack into the prevailing wisdom in Canadian historiography.

Lawson is insistent on the coincidental nature of any link between the Quebec Act and the American Revolution, affirming that there is no evidence that the inspiration for the Quebec Act was to placate the Canadians so as to keep them apart from the Americans. As this alleged link is one of the most tenacious myths in the Canadian historical consciousness, it is worth citing Lawson:

What can be done to dispose of this myth once and for all? Fifty years ago both Coupland and Burt said that they could find no evidence to justify such an assertion with Lanctot repeating the message in the 1960s, and nothing has yet come to light to contradict them (pp. 123-124).

When I first read this book in the early 1990s and realized how revolutionary his thesis was, I contacted Lawson to talk about his work. In passing, I mentioned that I supposed that The Imperial Challenge must have created quite a controversy in Canadian academic circles. His reply was “No, it has attracted very little attention in Canada.” (I never saw him again. I had arranged to see him a few years later, but just before I arrived in Edmonton he was admitted to hospital for terminal cancer and died shortly afterwards.) In subsequent years, I have been to McGill-Queens Press in Montreal to buy copies of his book to give to friends. Inquiring as to sales, I was told that only a few hundred copies had been sold. And, so far, I have encountered only one reference to Lawson’s book (in Yves Lamonde’s Histoire sociale des politiques au Quebec).

I was curious enough to go back recently to the reviews written when the book came out. There were 16 in Canada in French and English, in the United States and in the United Kingdom; all reviewers were quite positive except one (who wrote two of the reviews). They all commented positively on the extent and depth of the documentation, as well as the fresh reading from parliamentary debates, the personal archives of the principal players, and the press of the day. As for his interpretation of how the Quebec Act came to be, there is no suggestion that he was wrong in any respect. The negative reviewer suggests only that it is pretentious of Lawson to think he has added much to existing work on the Quebec Act. Of the 15 reviewers, a full half explicitly accredit Lawson with drawing out the intention of avoiding the error of Ireland.

Why, then, did a book, critically acclaimed by the author’s peers, which sheds considerable light on a pivotal period in the history of Quebec and Canada, drop out of sight in Quebec, and I suspect in the rest of Canada? Lawson calls into question the conventional wisdom on a very important subject in Canadian history, and no one takes notice. For instance, two prominent Canadians, Gerard Bouchard and John Raulston Saul, social thinkers who are presently reinterpreting Canadian history, make no mention, to my knowledge, of this book. A book that should have caused waves has generated scarcely a ripple.

Perhaps my assessment, as a non-professional historian, is faulty and I would welcome a demonstration of where I have erred. What are the factors that explain the untimely eclipse of Lawson’s work? Could it be simply that Canadian intellectual discourse is shallow, that a seminal work can be dropped into the water and hit bottom generating nothing more than a superficial ripple of perfunctory reviews and listings in compendiums? This is one possible explanation; a more certain explanation lies in ideology.

The ideological axe, starkly put, goes as follows. Quebec’s nationalist, republican-leaning contemporary intellectuals are loath to entertain the idea that a coterie of British Conservatives (half of them aristocrats) literally saved Quebec society by helping to keep it strong enough to withstand the renewed neo-liberal assault led by Lord Durham three quarters of a century later and, then, begin to rehabilitate the Quebec polity (under British institutions) in 1867. Such an idea being beyond the pale (again, the ghost of Ireland), they maintain the myth that the Quebec Act was political opportunism inspired by the American threat. What will it take for Quebec nationalist thinkers to recognize and appropriate the historical reality that Dorchester twice—in the Quebec Act and the siege of Quebec—saved Quebec? It is no exaggeration to assert that, had it not been for this one Anglo-Irish aristocrat, Quebec would likely have become anglicized and, subsequently, integrated into the American empire.

As for English-speaking Canada, the current crop of orthodox historians has long consigned our British imperialist past to the Marxist dust-heap of history: nothing good could possibly have come of it, all imperialisms being, by definition, bad. They are not about to disturb their orthodoxy that in contrast to Imperial Britain, which was incapable of any genuine sympathy for Quebec—only Canadian nationalist intellectuals are enlightened and respectful of Quebec society. So, they too maintain the “political opportunism” interpretation of the Quebec Act, despite its having been refuted by Lawson and his predecessors. Essentially, what we are seeing is a refusal to acknowledge a debt owed to dead white male Protestants (from Ireland and Scotland). But gratitude is not, as the contemporary French philosopher Alain Finkielkraut has pointed out, a hallmark of modern progressive thinkers.

I write this review knowing full well that it is too late for Lawson’s work to be rehabilitated. The Imperial Challenge is among the titles in this year’s McGill-Queen’s clear-the-warehouse sale.

Previously: Hitchcock in Quebec

Bon Voyage

Heading to Scotland for a little bit, then down to Somerset for a spell. Dino Marcantonio, you’re in charge!

Hitchcock in Québec

QUÉBEC, THAT STRANGE and charming province, is a most intriguing nation. It is where the British, French, and American tendencies clash and combine to form that most peculiar of all American varieties: le Québécois. Of course, since the 1960s Québec has become more French; no, not more French but more like France in that every year it plunges deeper into the depths of self-loathing: that hatred of one’s own tradition and history which has so marked out “the new Europe”. It is a race to assert one’s self by destroying any living connection to one’s past. Un jeu du fou. More’s the pity, as this once-vibrant melting pot of traditions expressed itself in interesting ways.

A splendid display of this Québec can be found in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1953 drama I Confess. The film had been recommended to me often and I finally got around to seeing it tonight. I won’t give away any of the plot, which is a good one, but Hitchcock lives up to his reputation with his excellent framing of the scenes. (Though I must admit, half of it is merely the settings in the Ville de Québec themselves). They include a peek into the Québécois Parliament. Above the Speaker’s dais is displayed not only the Sovereign’s arms, but also a crucifix, exhibiting our loyalties both temporal and spiritual. In the court room you find yet another blend of the Anglo and the French. As you no doubt recall from our handy little map, Quebec is a country with a mixed legal system. Founded as Nouvelle-France it had the civil system derived from the Romans. Captured by the British and later transformed into part of the Canadian Confederation, it has accrued layers of the Common Law so dear to we Anglos. The officials of the court wear British-style robes — the judge even has a tricorn hat — but over the jury looms a large crucifix. English government and French culture tempered by Catholic truth; not a bad mixture.

Anyhow, if you haven’t seen the film yet, here are a few snaps to enjoy until your Hitchcockian thirst is satiated. (more…)

Un Écossais en France

CHARLES GRANT, VICOMTE DE VAUX, was a Frenchman of Caledonian extraction who served as a sous-lieutenant in the Scots Company of the Garde du Roi, eventually rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. A cadet branch of the Scottish clan, the Grants in France made sure to maintain links with their kinsmen in the old country. Abbé Peter Grant helped Sir James Grant, 8th Bt., commence an art collection while Sir James was on the Grand Tour in 1759-60. Abbé Grant’s nephew, Baron Grant de Blairfindy, was a fellow Catholic and Colonel in the Légion Royale of Louis XVI.

In a letter to Sir James, who was Chief of the Grants, Blairfindy described their fellow kinsman the Vicomte de Vaux as “a clever, brave officer, polite in company… as brave as his sword,” though, rather disappointingly, the Baron adds that the Vicomte “never drinks”. De Vaux himself took a keen interest in his extended family, and when the terrors of the French Revolution forced him into exile in London, he published there his Mémoires de la Maison Grant depicting the history of the clan. (more…)

The Prince of Wales in Philadelphia

THE CITY OF PHILADELPHIA welcomed the Prince of Wales on his recent visit with a guard of honor composed of members of its most ancient military unit, the First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry. Organized in 1774 as the Light Horse of the City of Philadelphia, it describes itself as the “oldest continuously active military unit in service to the nation”. As an active armored cavalry troop, it forms part of the 28th Division, while as an historic and ceremonial unit it is a component of the Centennial Legion (of which my grandfather served as commander). Since the most unfortunate demise of New York’s Seventh Regiment, it probably takes the prize for swankiest unit in the States.

Previously: Old Dominion Will Receive Her Majesty | The Duke of York in New York | Your Royal Highness, Caed Mile Failte

A Sienese Gem Lost

STEALING A GLANCE at the photo above, the viewer would easily be forgiven for mistaking the vista for that of a subway entrance in turn-of-the-century Siena, Italy. The proud medieval tower lurks over a comely metal-and-glass structure of continental flavor. However the city fathers of that ancient Italian municipality never deigned to erect an underground railway. The precise locus of the vista is far removed: it is the corner of Park Avenue and 33rd Street, and the building behind the subway entrance is not the town hall of Siena, but rather the armory of the 71st Regiment, New York National Guard.

When the earlier Romanesque Revival armory of the Seventy-First Regiment burnt down in 1902, it was decided to build the new armory on the same, though slightly enlarged, site. The 1905 construction was built to the design of the architectural firm of Clinton and Russell, and was clearly inspired by the Palazzo Pubblico (the town hall, photo at right) of Siena, on that city’s Piazza de Campo. While the Seventh Regiment Armory contains the finest interiors of any military building in City, and probably the entire Empire State, the exterior of the Seventy-First’s armory was far superior. Even though the interior was not to the same lofty standard as the Seventh, it was by no means lacking, for it had all the wood-panelled rooms filled with military regalia from times gone by which one expects of New York’s armories from the period. (more…)

When the earlier Romanesque Revival armory of the Seventy-First Regiment burnt down in 1902, it was decided to build the new armory on the same, though slightly enlarged, site. The 1905 construction was built to the design of the architectural firm of Clinton and Russell, and was clearly inspired by the Palazzo Pubblico (the town hall, photo at right) of Siena, on that city’s Piazza de Campo. While the Seventh Regiment Armory contains the finest interiors of any military building in City, and probably the entire Empire State, the exterior of the Seventy-First’s armory was far superior. Even though the interior was not to the same lofty standard as the Seventh, it was by no means lacking, for it had all the wood-panelled rooms filled with military regalia from times gone by which one expects of New York’s armories from the period. (more…)

King Jagiello of Poland

My favorite statue in Central Park is that of King Władysław II Jagiełło of Poland, by the Turtle Pond. (more…)

The Cardinal Duke of York

The great Marco Foppoli has designed (and very kindly passed along to me) the badge for the committee which has been assembled to commemorate the two-hundredth anniversary of the passing of the Cardinal Duke of York, or King Henry IX and I as was his style according to the Jacobite succession. I’m not entirely sure what events are being planned, but I believe there will be a conference in Rome around the anniversary in August.

Drink Audit Ale in Heaven With Me

I pray good beef and I pray good beer

This holy night of all the year,

But I pray detestable drink to them

That give no honour to Bethlehem.

May all good fellows that here agree

Drink Audit Ale in heaven with me,

And may all my enemies go to hell!

Noel! Noel! Noel! Noel!

May all my enemies go to hell!

Noel! Noel!

WITH THESE SIMPLE and lovely lines, Hilaire Belloc superbly expressed the esprit de Noël of the Christian curmudgeon. It amounts, more or less, to “Rend honor to the Holy Child, and to hell with the rest”.

His Lines for a Christmas Card are obviously meant in a jovial and light-hearted spirit (naturally, we would not wish Hell on any poor soul) and are completely intelligible but for this curious line: “May all good fellows that here agree / Drink Audit Ale in heaven with me”. What on earth is Audit Ale?

Before the Reformation, the English year was a calendar of feasts, festivals, and holidays — holy days, even. Four of these holy days, spaced fairly evenly throughout the year, were marked for such things as the collection of rents and the paying of feudal tributes. These four were Lady Day (March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation), Midsummer Day (June 24, the Feast of St. John the Baptist), Michaelmas (September 29, the Feast of St. Michael the Archangel), and Christmas (December 25, of course, the Feast of the Nativity of Christ).

Now, events such as the collection of fees and taxes and the giving of feudal tribute tend towards the dour, and so often a feudal lord would have a special ale brewed for these occasions, to ensure a certain amount of merriment among the commonfolk once their tribute had been paid and the burden lifted. This tended to be called ‘audit ale’, since it was brewed around the time of audit.

They were not, you will be happy to learn, the only seasonal brews around. There was ‘leet-ale’ for when the manorial court, or court-leet, convened, and there was Whitsun-ale for Whitsuntide, and there were church-ales which went towards the upkeep of the parish church and alms for the poor. Indeed, in village of Sygate in Norfolk, there is an inscription on the gallery of the church which reads:

And give us good ale enow . . .

Be merry and glade,

With good ale was this work made.

Also, interestingly, the very word ‘bridal’ comes not from the -al suffix English developed up from Latin, but rather from the Old English brýd-ealo: bride-ale or wedding-ale.

With the advent of Protestantism — and most especially the Puritan variant thereof — feasts, seasons, and other joviality generally became frowned-upon. England was forced to be less English, as the monotonous bores took over.

Still, remnants of the feasts and seasons remained. Lady Day was the first day of the year in Great Britain and its empire until 1752, when the Gregorian calendar was finally adopted. Similarly, the fiscal year in the United Kingdom begins on April 6 because that day in the Gregorian calendar corresponds to Lady Day in the old Julian calendar.

In Oxford and Cambridge, meanwhile, colleges still brewed special ales for the time when grades were released; either to celebrate the achievement or to soften the blow. These brews kept the old moniker of ‘audit ales’ and Belloc most likely uses the term in this derivation. Even in my own time at St Andrews we often sipped home-brewed ale from ancient, battered pewter tankards, though we rarely needed the excuse of holy days to continue the tradition.

In Oxford and Cambridge, meanwhile, colleges still brewed special ales for the time when grades were released; either to celebrate the achievement or to soften the blow. These brews kept the old moniker of ‘audit ales’ and Belloc most likely uses the term in this derivation. Even in my own time at St Andrews we often sipped home-brewed ale from ancient, battered pewter tankards, though we rarely needed the excuse of holy days to continue the tradition.

So this Yuletide perhaps you will consider home-brewing, and brew a special ale for the festal season now that the penetential time of Advent is passing. But, if you’re otherwise engaged, head into town and make sure to have a beer, and raise your pint to that Wondrous Babe whose birth brings us such mirth and cheer.

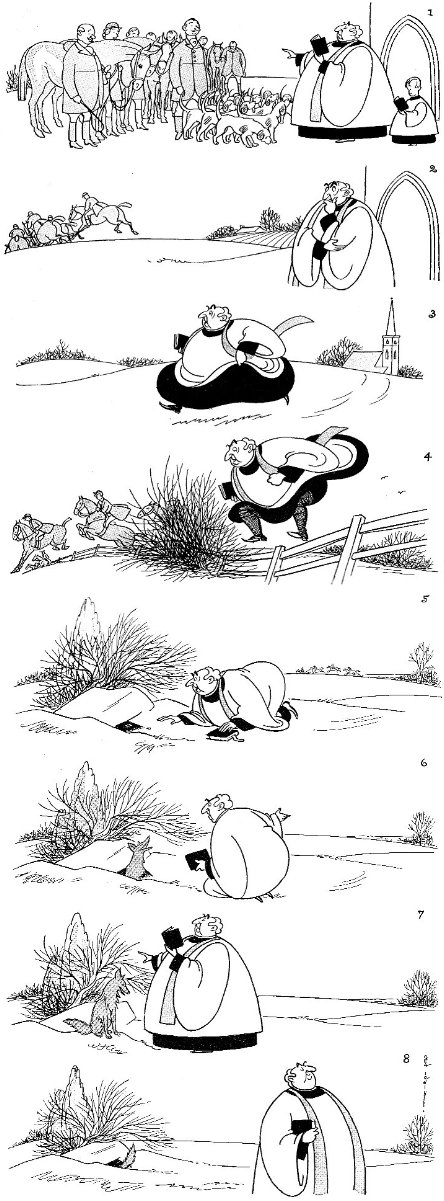

The Vicar’s Remorse

Previously: New York in November | The New Yorker Hunts | Tally Ho, Empire State!

Governors Island Revisited

EVERY ONE OF THE myriad plans put forth for the ‘redevelopment’ of the venerable old Governors Island in New York Harbor has so far either stalled, been neglected, or otherwise poo-pooed. In this, we have something to rejoice. As I have often said, realistically speaking there is little that can be done to it which will not neglect or disgrace the island’s long military heritage. The officially-approved ideas put forth so far have been horrific: an amusement park, a casino, a ‘technology park’, as well as a number of other vapid proposals.

Naturally, we’d be enthused if it returned to its former role as swankiest post in the entire Army and the home of Army polo, but don’t hold your breath. West Point being the single exception, if it has even a touch of history, tradition, or class, Congress and the Department of Defense will do their best to get rid of it. After all, the National Guard has been pulled out of the Seventh Regiment Armory, the Navy has withdrawn all but a few institutions from Newport, and the Army has left the ancient Presidio of San Francisco; how long will it be until Fort Leavenworth’s foxhounds are brought out back and shot by the Monotony Monitors? (more…)

New York in November

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories