Tradition

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Patrick in Parliament

The Mosaic of Saint Patrick in the Palace of Westminster

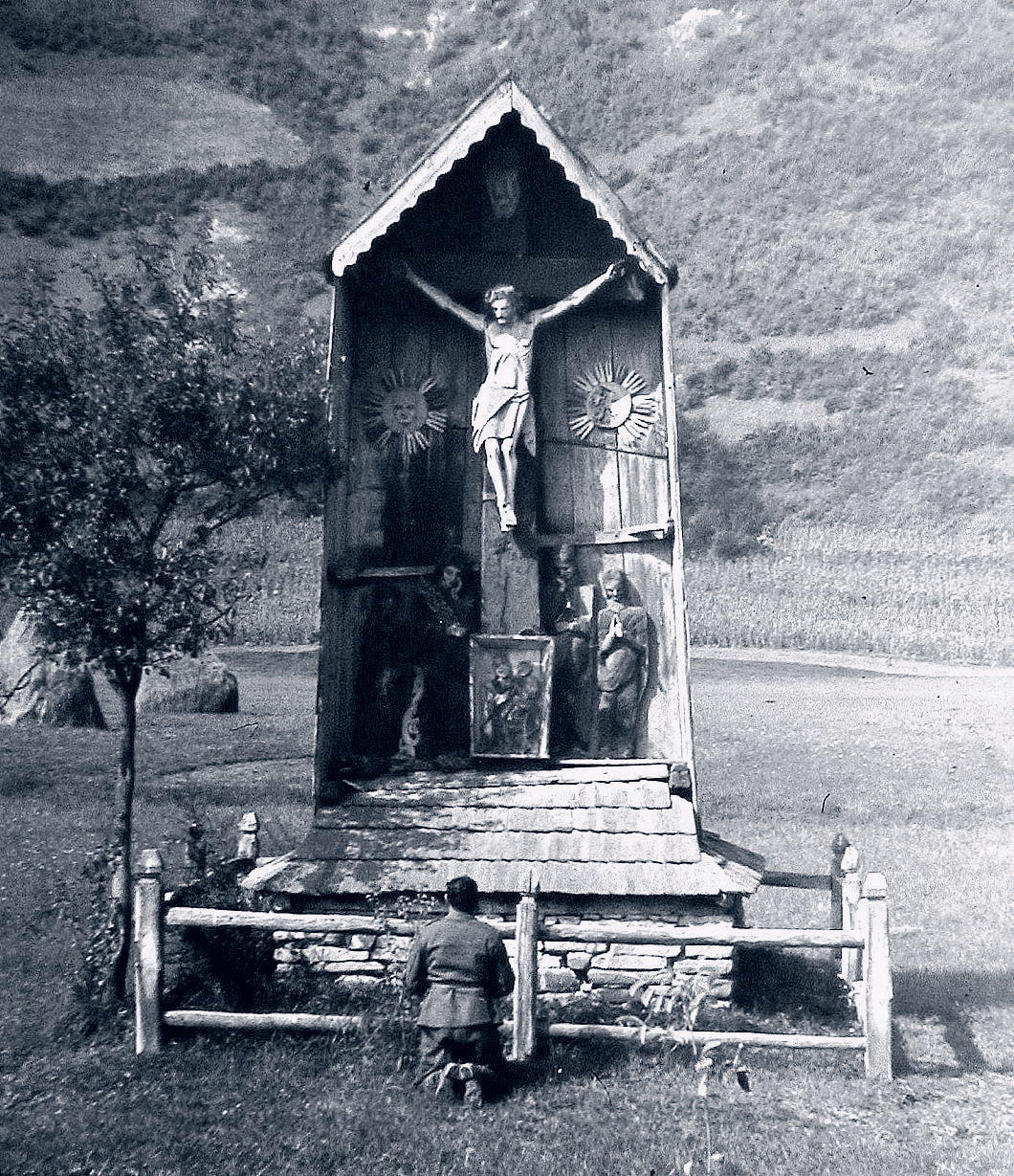

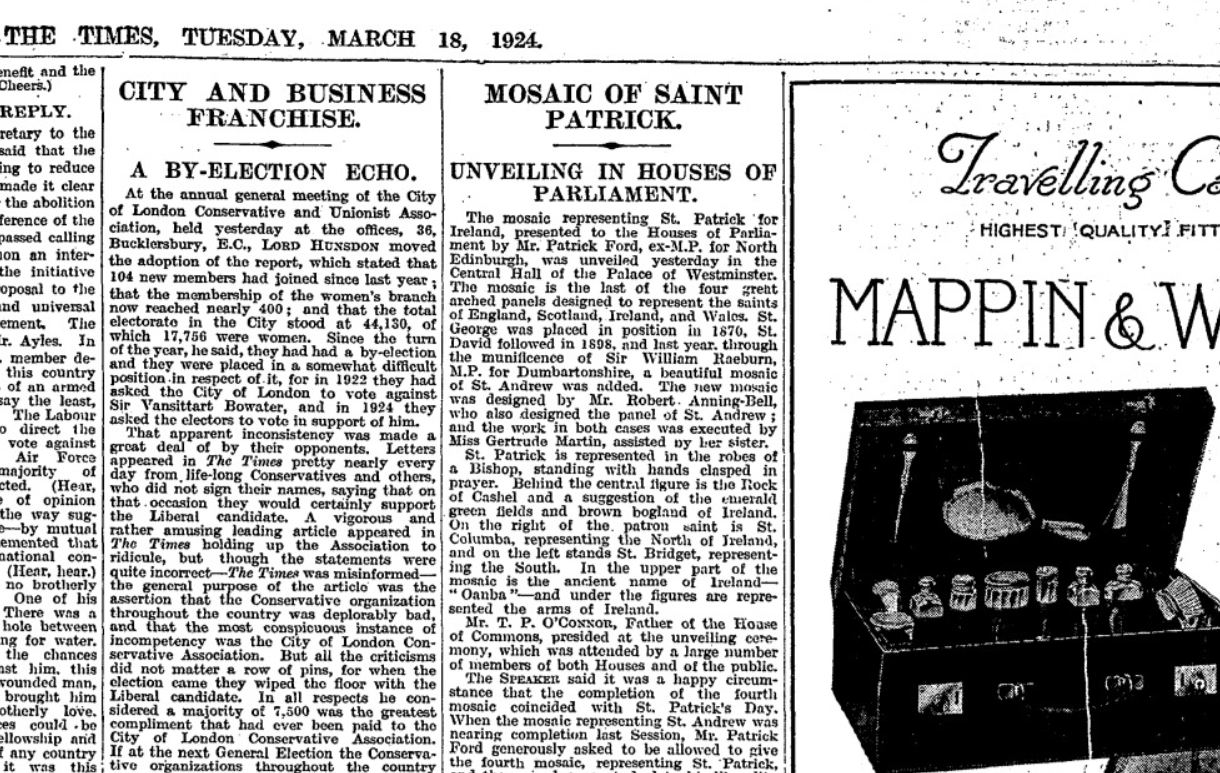

This feast of St Patrick marks the hundredth anniversary of the mosaic of Saint Patrick in the Central Lobby of the Houses of Parliament. At the heart of the Palace of Westminster, four great arches include mosaic representations of the patron saints of the home nations: George, David, Andrew, and Patrick.

The joke offered about these saints and their positioning is that St George stands over the entrance to the House of Lords, because the English all think they’re lords. St David guards the route to the House of Commons because, according to the Welsh, that is the house of great oratory and the Welsh are great orators. (The English, snobbishly, claim St David is there because the Welsh are all common.) St Andrew wisely guards the way to the bar (a place where many Scots are found), while St Patrick stands atop the exit, since most of Ireland has left the Union.

The mosaic of Saint Patrick came about thanks to the munificence of Patrick Ford, the sometime Edinburgh MP, in honour of his name-saint. Saint George had been completed in 1870 with Saint David following in 1898.

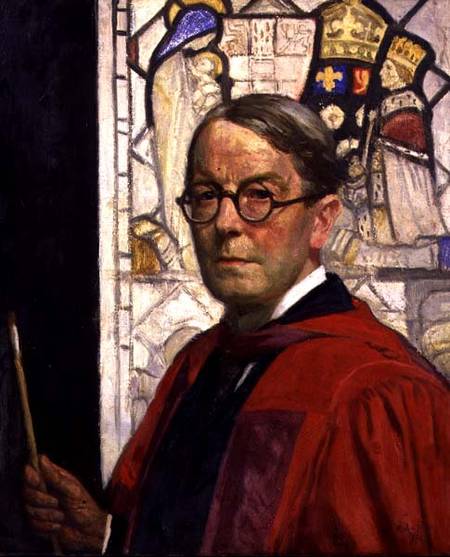

Sir William Raeburn MP commissioned the artist Robert Anning Bell (depicted right) to design the mosaic of Saint Andrew in 1922, which so impressed Patrick Ford that he decided to commission the same artist to depict the patron saint of Ireland.

Sir William Raeburn MP commissioned the artist Robert Anning Bell (depicted right) to design the mosaic of Saint Andrew in 1922, which so impressed Patrick Ford that he decided to commission the same artist to depict the patron saint of Ireland.

Anning Bell had earlier completed the mosaic on the tympanum of Westminster Cathedral from a sketch by the architect J.F. Bentley. Following his work in Central Lobby he also did a mosaic of Saint Stephen, King Stephen, and Saint Edward the Confessor in Saint Stephen’s Hall — the former House of Commons chamber.

In the mosaic, Saint Patrick is flanked by saints Columba and Brigid, with the Rock of Cashel behind him. As by this point Ireland had been partitioned, heraldic devices representing both Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State are present.

On St Patrick’s Day in 1924, the honour of the unveiling went to the Father of the House of Commons, who happened to be the great Irish nationalist politician T.P. O’Connor, then representing the English constituency of Liverpool Scotland (the only seat in Great Britain ever held by an Irish nationalist MP).

“That day,” The Times reported T.P.’s words at the unveiling, “in quite a thousand cities in the English-speaking world, Saint Patrick’s name and fame were being celebrated by gatherings of Irishmen and Irishwomen. Certainly he was the greatest unifying force in Ireland.”

“All questions of great rival nationalities were forgotten in that ceremony. From that sacred spot, the centre of the British Empire, there went forth a message of reconciliation and of peace between all parts of the great Commonwealth — none higher than the other, all coequal, and all, he hoped, to be joined in the bonds of common weal and common loyalty.”

T.P.’s remarks were greeting with cheers.

The Most Honourable the Marquess of Lincolnshire, Lord Great Chamberlain, accepted the ornamental addition to the royal palace of Westminster on behalf of His Majesty the King.

Articles of Note: 13 March 2024

My then-flatmate was getting married the next day and much pottering-about sorting things was required but the idiosyncratic beauty of this building captured my imagination — part Norman, part Moorish. I was almost insulted that I hadn’t come across it in any of my bookish explorations.

The historian Edmund Harris covers Chideock in his lusciously illustrated post on Recusancy in Dorset and the ‘other tradition’ of Catholic church-building.

■ Generations ago it was said that the three institutions no British politician dared offend were the trade unions, the Catholic Church, and the Brigade of Guards. In 2020s Britain there is only one caste which must always be obeyed: the ageing, moneyed homeowners.

Not only do these “NIMBYs” (“Not In My Back Yard”) jealously guard their freeholds, they do whatever they can to prevent more houses being built to guard the value of their prize possessions, vastly inflated by a combination of lacklustre housebuilding and irresponsible leap in migration. As old people vote and young people don’t — and when they do, vote badly — few sensible people can find a way out of this quagmire.

It might be worth looking to the Mediterranean, where Tal Alster tells us How Israel turned urban homeowners into YIMBYs.

■ It’s disappointingly rare to see intelligent outsiders give a considered impression of the current state of play in the Netherlands — that’s Mother Holland for us New Yorkers. Too often commentators in English are either rash cheerleaders for the hard right or bien-pensant liberals eager to castigate and chastise. Both rush to judgement.

What a rare diversion then to read Christopher Caldwell — the only thinking neo-con? — attempt to explore and explain the success of Geert Wilders in the recent Dutch elections.

■ One in ten of Lusitania’s inhabitants are now immigrants, and this discounts those — many from Brazil and other former parts of the once-world-spanning Portuguese empire — who have managed to acquire citizenship through various routes.

Ukrainian number-plates are now frequently be seen on the roads of Lisbon, as far in Europe as you can get from Big Bad Uncle Vlad.

Vasco Queirós asks: Who is Portugal for?

■ Speaking of world-spanning empires, in true andrewcusackdotcom fashion, we haven’t had enough of the Dutch — but we have had enough of their wicked wayward heresies.

Historian Charles H. Parker explores the legacies of Calvinism in the Dutch empire.

■ The City of New York itself is the best journalism school there is. Jimmy Breslin dropped out of LIU after two years, eventually taking up his pen. Pete Hamill left school at fifteen, apprenticed as a sheet metal worker, and joined the navy.

William Deresiewicz argues that a dose of working-class realism can save journalism from groupthink.

■ The New Yorker tells us how a Manchester barkeep found and saved a lost (ostensible) masterpiece of interwar British literature.

■ Our inestimable friend Dr Harshan Kumarasingham explores David Torrance’s history of the first Labour government on its hundredth anniversary.

■ And finally, one for nous les normandes (ok, ok, celto-normandes): Canada’s National Treasure David Warren briefly muses that the Norman infusion greatly refined Anglo-Saxon to give us the superior English tongue we speak today.

Cambridge

There’s a Dutch vibe to Cambridge that I rather like — but also a lingering Protestant Cromwellianism that I don’t. These two factors are not unconnected, and the highway that once was the North Sea is not so far away.

It is not a bad town. It’s like they took Oxford apart, put it back together again in not quite the same way, and added a lot of Regency infill. Oxford is more mediaeval, Georgian, and neo-mediaeval, whereas Cambridge is mediaeval, Tudor, and Regency.

The Cam is slower, quieter, and more peaceful than the Isis, which again gives it the quality of a Hollandic canal. I suspect the punting is better — or at least easier — here than at Oxford.

And of course it is rather more spacious than Oxford, which is hemmed in by geography in a way that Cambridge isn’t.

But it is also eerily quieter. A smart restaurant on a Thursday night was dead by half ten, and the staff refused our plaintive request for a second round of Tokay. (Protestantism.)

Taken on Trust

There is much talk these days of the nature of “high trust” societies and the many benefits which they bring, or once brought in the case of countries like Great Britain that, until relatively recently, fell into this category.

The young Lee Kuan Yew (1923-2015) was astounded when he exited the Underground station at Piccadilly Circus and saw a pile of newspapers and a box of coins and notes, with passers-by being trusted to pay for their own newspaper and calculate their own change. He determined that Singapore must emulate the high trust society that Britons had inherited.

In his excellent book, Britain Against Napoleon: The Organization of Victory 1793-1815, about the logistics of Britain’s fight against Old Boney, Roger Knight writes of how much trade and agriculture across Great Britain relied upon this trust.

Drovers, for example, would take on thousands of pounds worth of animals — pigs, cattle, etc. — from farmers to drive down to London en masse, not returning for weeks, and usually with little or no paper record.

Citing Bonser’s The Drovers: Who They Were and How They Went, An Epic of the English Countryside, Knight relays the following story:

Perhaps the most impressive demonstration of trust was the tradition of dogs being sent home to Scotland or Wales from London on their own. One story involved a Welsh dog named Carlo who journeyed all the way back to Wales from Kent. His owner sold the pony that he had ridden on the outward journey, intending to go home by coach. He fastened the pony’s harness to the dog’s back and attached a note to it, addressed to each of the inns on the route they had followed, to request food and shelter for the dog, to be repaid on a subsequent journey. Carlo reached home in Wales alone in a week.

Even dogs benefited from a high-trust society.

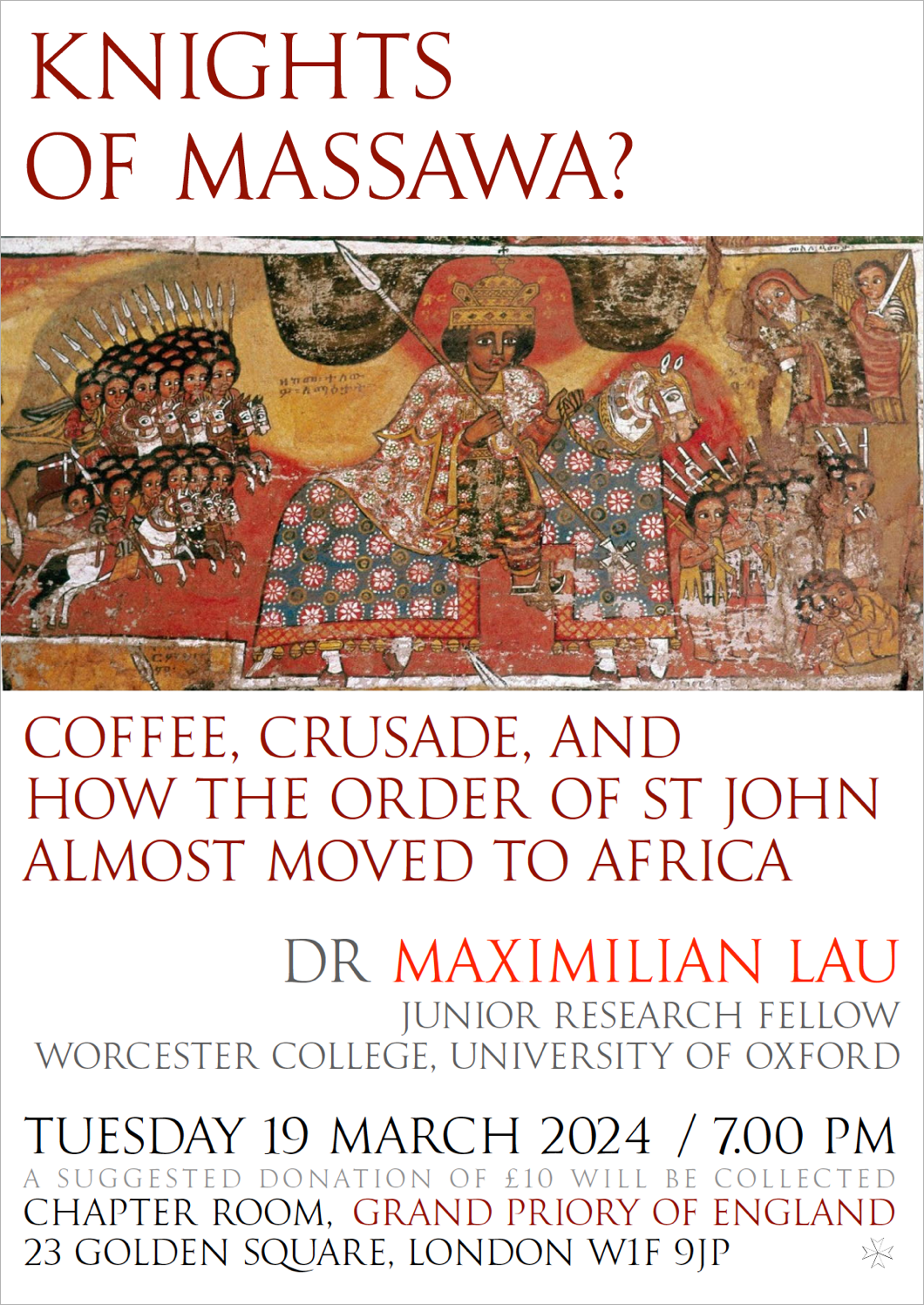

‘Knights of Massawa?’ Lecture

This will take place in the Chapter Room of the Grand Priory of England at 7.00 pm on Tuesday 19 March 2024.

All are welcome, and a voluntary contribution of £10 will be collected.

Messing About in Old New York

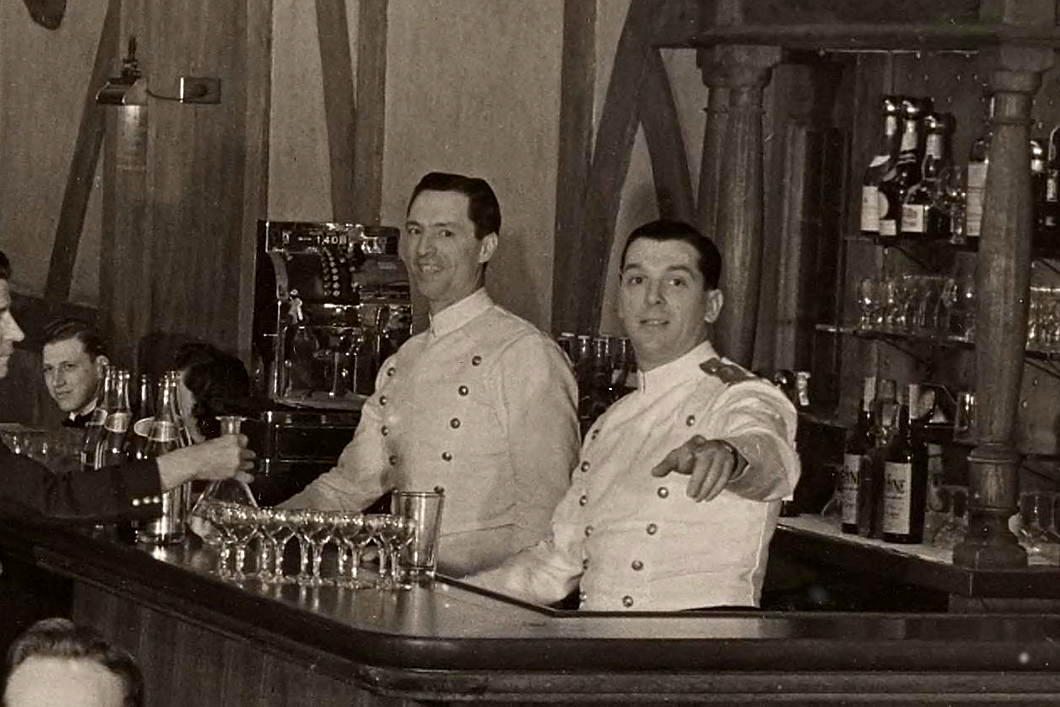

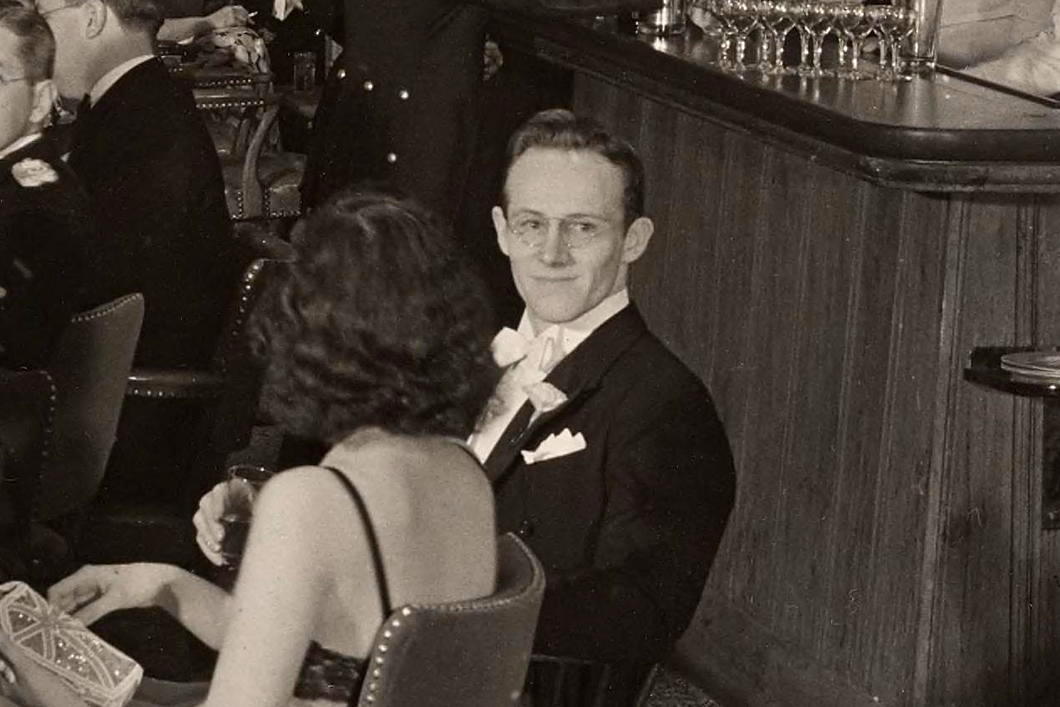

In the collections of the New-York Historical Society there is a photograph deposited amidst the archives of the Seventh Regiment Gazette.

The scene is the Appleton Mess of the Seventh Regiment Armory on Park Avenue, where Company B of the “Silk-Stocking Regiment” was celebrating its one-hundred-and-thirty-fourth birthday.

It was May 1940. The other side of the Atlantic Ocean, British troops were evacuating from Norway, sparking the debate in the House of Commons that would lead to Winston Churchill being appointed Prime Minister.

But on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, all was still peaceful and calm.

With a packed calendar of events, the social life of B Company was as much of a whirl as any other in the Seventh Regiment.

“The members of the Second Company greeted the onrushing spring with a cocktail party and dance on the afternoon of February 11th,” the Gazette reported. “The time-stained rafters of the Veterans Room echoed back as melodious a medley of sweet, swing, and hot as these old ears have heard in many a year.”

“The spaghetti lovers are still meeting down at Tosca’s on Tuesdays,” the Gazette continued. “All members who drop in on this crowd are warned beforehand to eat fast and keep an eye on their plate. A darting fork awaits all unwatched portions and men have been known to sit down to a full dish of Italian cable only to arise half famished.”

Company B’s Entertainment Committee also found time for a Supper Dance at the end of March that year: “When Charley Botts heard ‘In The Mood’ he gathered up the jitterbugs and sent them scampering around in a breathless Big Apple, much to the delight of the wiser and unbruised amongst us who resisted his wiles.”

“Several of the more energetic members closed the evening by visiting that well-known late spot, the Kit-Kat Club, and are now offering mortgages on the family homestead to settle future bills.”

All the faces, the mode of dress — it’s a picture of a vanished New York, a year and a half before the attack on Pearl Harbor. (Incidentally, December 7, 1941 was also the day Col. Cusack — aka ‘Uncle Matt’ — was baptised.)

On another level, it looks just like the Seventh Regiment Mess I knew from my childhood, when it was in the firm but welcoming hands of Linda MacGregor.

The building has been restored physically but since the military was kicked out it is a beautiful but lifeless hulk, preserved as if in formaldehyde and reduced to being a mere “venue”.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

St Mary Overie in Lent

Here in Southwark I nipped in to Evensong in the late twilight of a winter’s day. They do it very beautifully with a full choir at the Protestant cathedral — old Southwark Priory or St Mary Overie to us Catholics, St Saviour’s to our separated brethren.

As it is the penitential season, the Lenten Array is up at Southwark Cathedral, theirs apparently designed by Sir Ninian Comper.

What is a Lenten Array? Sed Angli writes on the Lenten Array in general while Dr Allan Barton has written on Southwark Cathedral’s Lenten Array specifically.

And of course our friend the Rev Fr John Osman has one of the most beautiful Lenten Arrays at his extraordinary Catholic parish of St Birinus — a stunning church previously mentioned.

(The photograph of our local array is from Fr Lawrence Lew O.P.)

Regnum, Ecclesia, Studium

The threefold division of the world

As such he might be expected to have ideas about the idea of a university, and he wrote about them in The Spectator in August 1983.

Mister Grimond (as he still was then, only just), suggested those interested in the subject “might turn to a lecture by Ronald Cant, sometime Reader in Scottish History in the University of St Andrews”:

[…]

A vital aspect of this tripartite organisation, as Cant says, was that each should serve and support the other. But the studium, while interacting with the regnum and ecclesia, must maintain its independence.

It was certainly the business of the studium to advance knowledge, but that was not to be the end of the matter. Knowledge was linked to public service. The learned man had a duty to the community as well as a right to pursue his intellectual quarry. In fact he pursued the quarry on behalf of the community.

The tripartite division of the world, although old-fashioned, seems to me a useful concept, emphasising that government, morality, and higher education are separate but intertwined.

It seems to me that if we expel the regnum and the ecclesia utterly from the world of the university we shall end up paradoxically with universities totally dependent upon the state… but as subservient as those in Rome.

The liberal spirit gave birth and sustenance to universities; if its progeny does not foster it in the regnum they may indeed end up as purely vocational colleges.

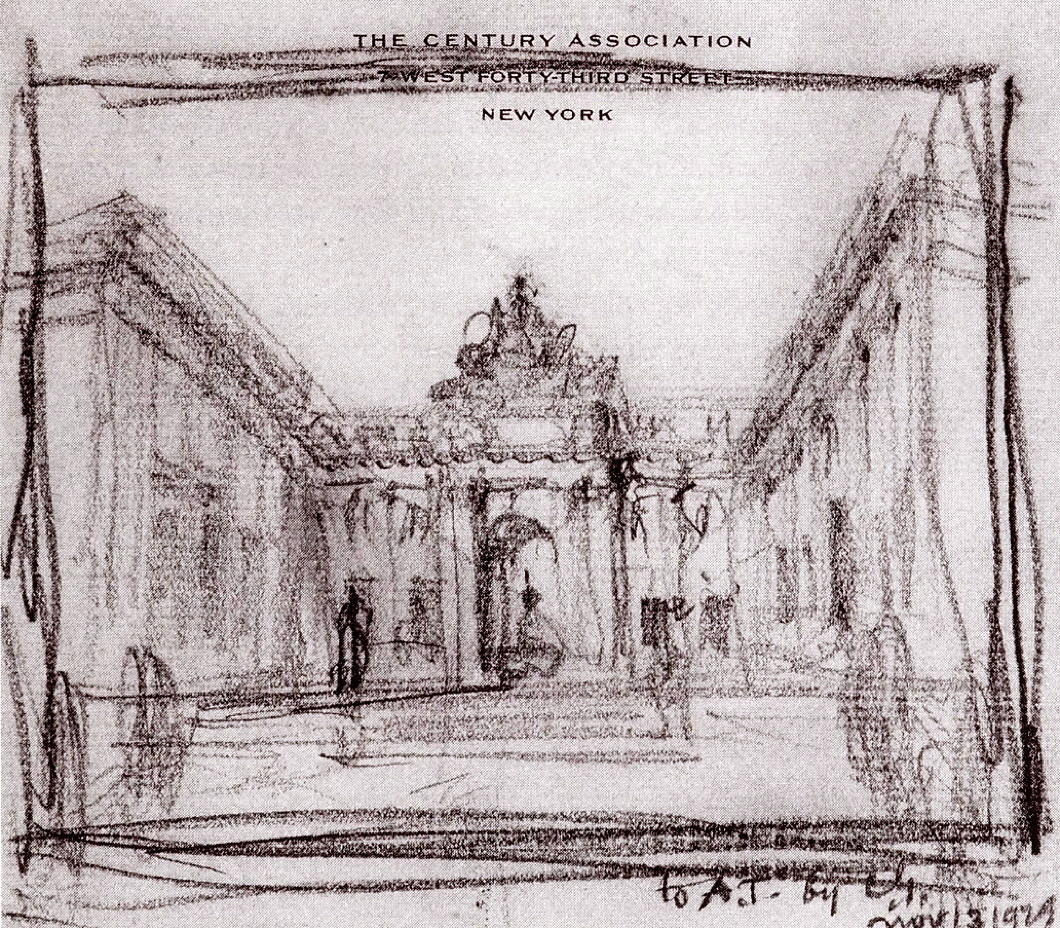

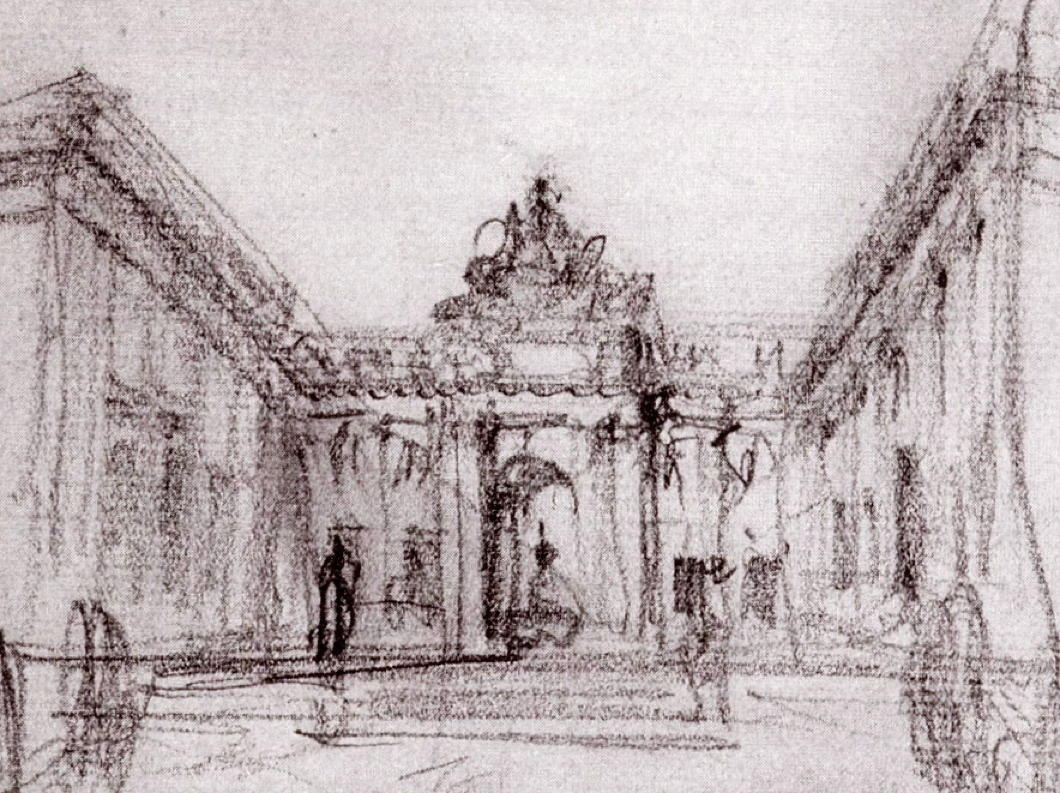

Unfinished Business at Audubon Terrace

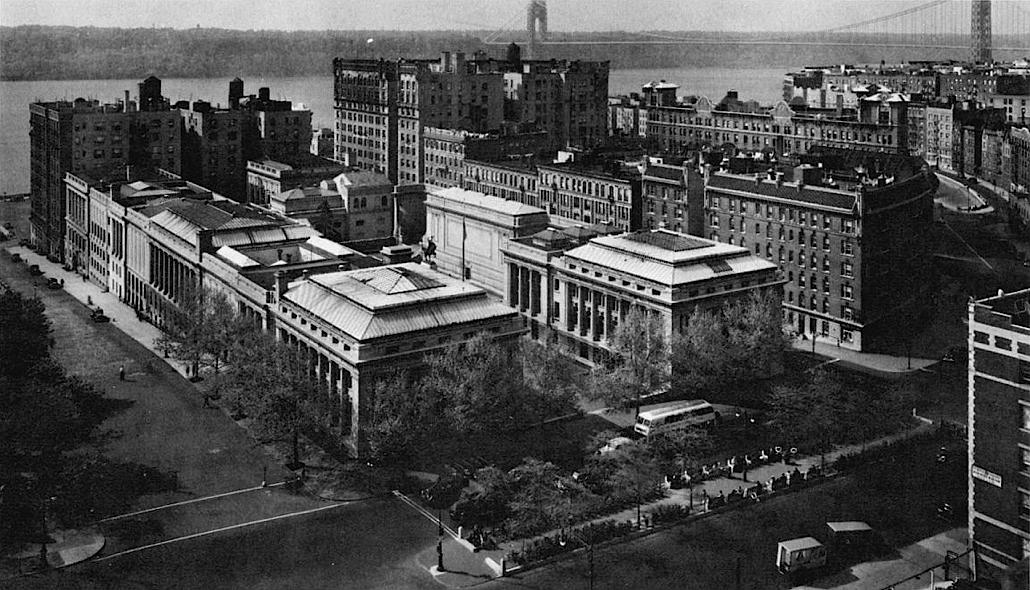

One of the little tragedies of New York urbanism is that when Archer Milton Huntington was transforming a block of upper Manhattan into an acropolis of culture he failed to buy the entire block.

Huntington named his complex Audubon Terrace in honour of the artist and ornithologist John James Audubon whose home, Minniesland, overlooked the Hudson at the western end of the block. His failure to obtain Minniesland meant that the remainder of the block was snapped up by developers instead of incorporated into his campus.

In the 1910s, the speculators built apartment buildings that turned their rather rude and unadorned backs to Audubon Terrace, terminating the vista from Broadway. When you imagine the potential prospect all the way to the river, it is all the more tragic.

The crass posterior of these apartment blocks naturally dissatisfied the members of the American Academy of Arts & Letters, whose building sits on either side — and indeed beneath — the part of the terrace immediately adjacent to them.

McKim Mead & White had designed the first phase of the Academy’s handsome building facing on to West 155th Street, which opened in 1923, and Cass Gilbert was chosen to design the auditorium and pavilion which would complete the body’s portion of the site.

The Academy used the pavilion for art exhibitions and other events, with the terrace in between serving as a useful spot for springtime drinks parties for the academicians and their many guests.

The infelicitous nature of their neighbours clearly irritated the Academy, and in 1929 they had a conversation with Cass Gilbert about designing some sort of screen to satisfyingly terminate the vista down Audubon Terrace and block the view of the apartment buildings.

Gilbert sketched out a plan to build an arched screen connecting the pavilion to the main building across the terrace, topped off by a sculptural flourish.

There is a danger its scale may have overwhelmed the space, but that seems a preferable struggle to face when compared to the problem of the rude neighbours.

Events, as they so often do, intervened. The Wall Street Crash badly affected the American Academy’s finances, and Archer Huntington was forced to increase his already generous subsidy to the body even more just to make ends meet.

Gilbert’s final completion of Audubon Terrace was not to be.

The Academy was founded as a bastion of the old guard against the avante-garde, but in recent decades it has let its hair down a little, and leans more towards the modern than the traditional.

All the same, its current president is an English-public-school-and-Cambridge-educated philosopher from one of the most aristocratic families in Ghana, so it’s reassuring they’re keeping a bit of the old with the new.

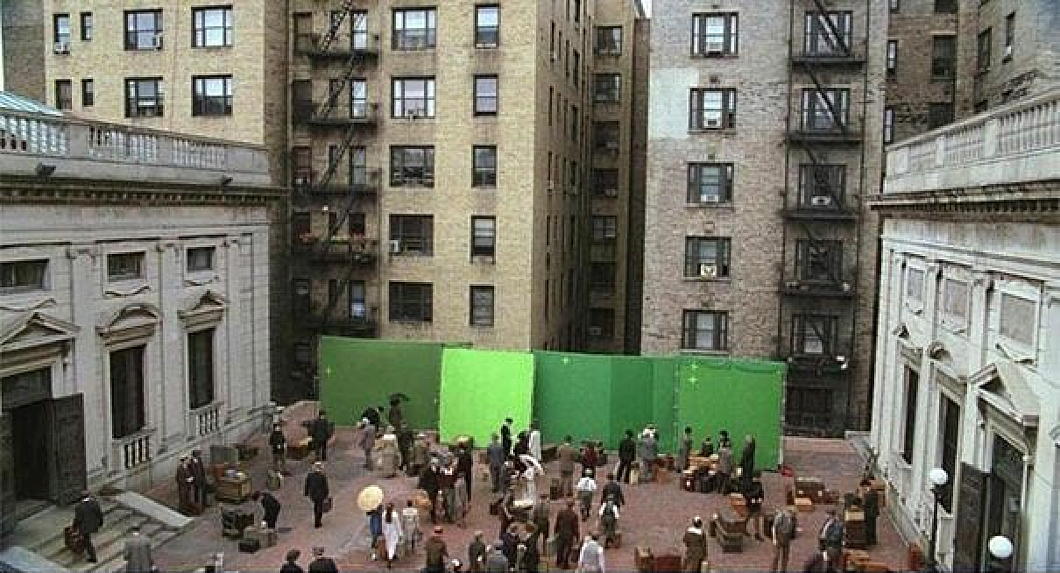

The terrace is often used as a filming location for cinema and television, given the high quality of its architecture and the fact that it is visually not well-known even among New Yorkers, so can be deployed as a foreign setting.

The HBO programme ‘Boardwalk Empire’ used the American Academy’s terrace as an Italian port, using green screens (instead of a Cass Gilbert monumental arch) to transform the piazza.

Audubon Terrace and its surviving institutions — the expanding and renovating Hispanic Society, the American Academy of Arts & Letters, and the Church of Our Lady of Esperanza — are an intriguing hidden gem of upper Manhattan, well worth a visit.

I don’t imagine anything like Cass Gilbert’s screen will ever be built, but every time I drop in to this neck of the woods I can’t help but thinking there’s some unfinished business.

Dom Miguel de Castro

During the 1640s, a conflict arose between Kongo’s pious and militarily successful King Garcia II and his vassal, the Count of Sonho. Seeking the help of the Dutch Republic and its stadtholder, the Count sent his cousin, Dom Miguel de Castro, to the Netherlands as an emissary.

Dom Miguel arrived at Flushing in June 1643 and proceeded to Middelburg where he was received by the Zealand chamber of the Dutch West India Company.

During the Kongo nobleman’s fortnight in Middelburg, the chamber commissioned these portraits of Dom Miguel and his two servants painted by Jasper Becx — or possibly by his brother Jeronimus.

The Zealand chamber gave the trio of portraits to Johan Maurits — Prince of Nassau-Siegen, governor of Dutch Brazil, and originator of the Mauritshuis — who in 1654 gave them to Frederik III of Denmark, along with twenty Brazilian paintings by Albert Eckhout.

A full-length portrait of Dom Miguel was taken back to Africa by him and, alas, is now lost.

Dom Miguel de Castro

Jaspar Beckx, c. 1643;

Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Dom Miguel de Castro

Jaspar Beckx, c. 1643;

Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

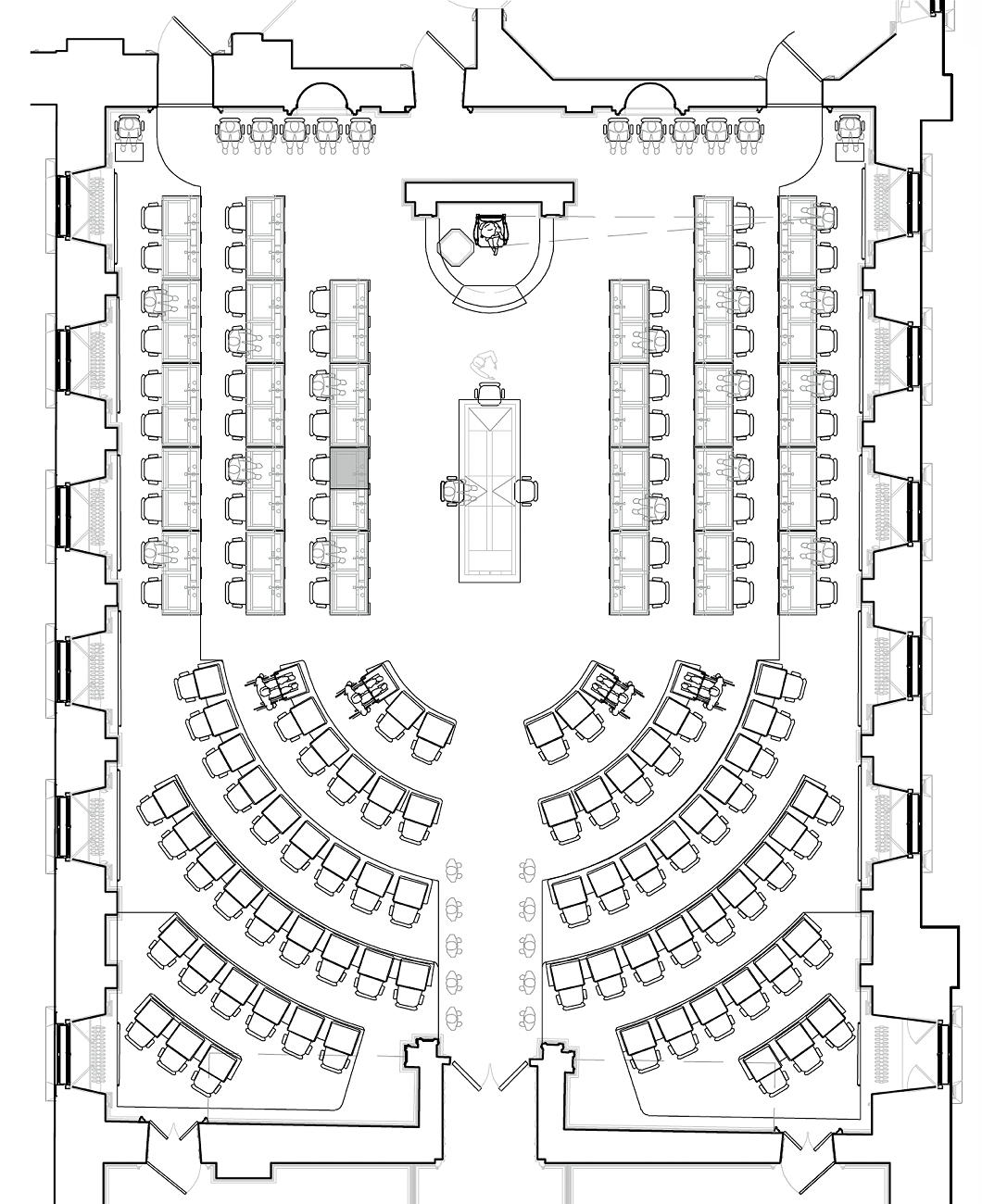

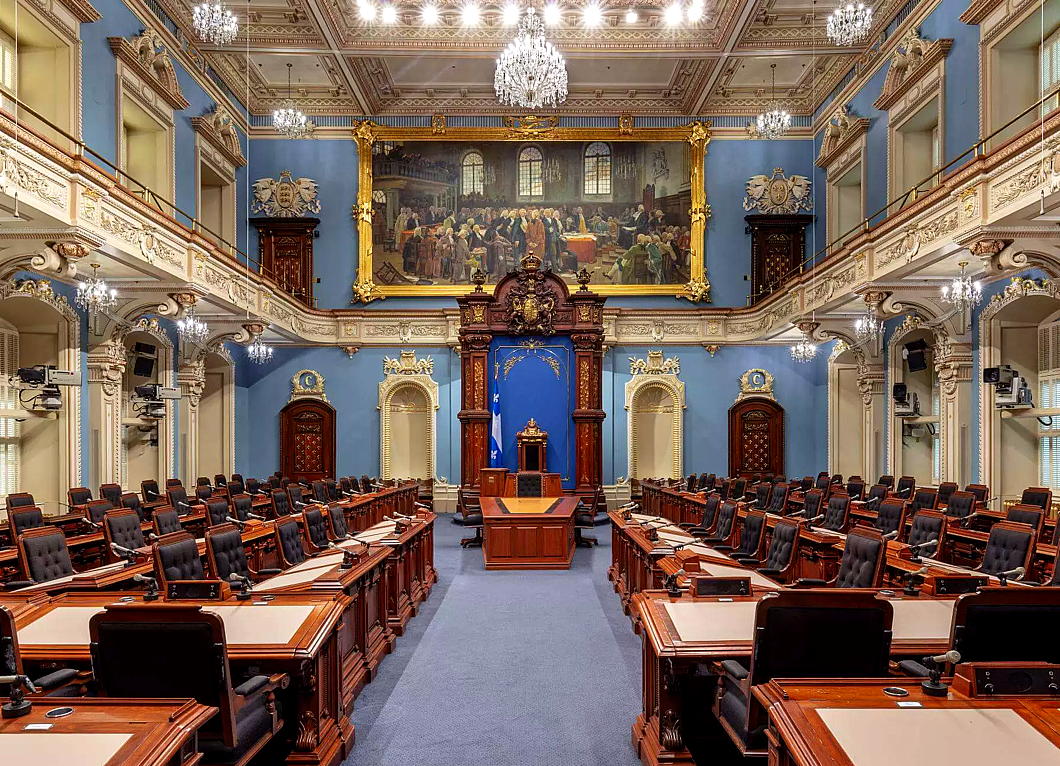

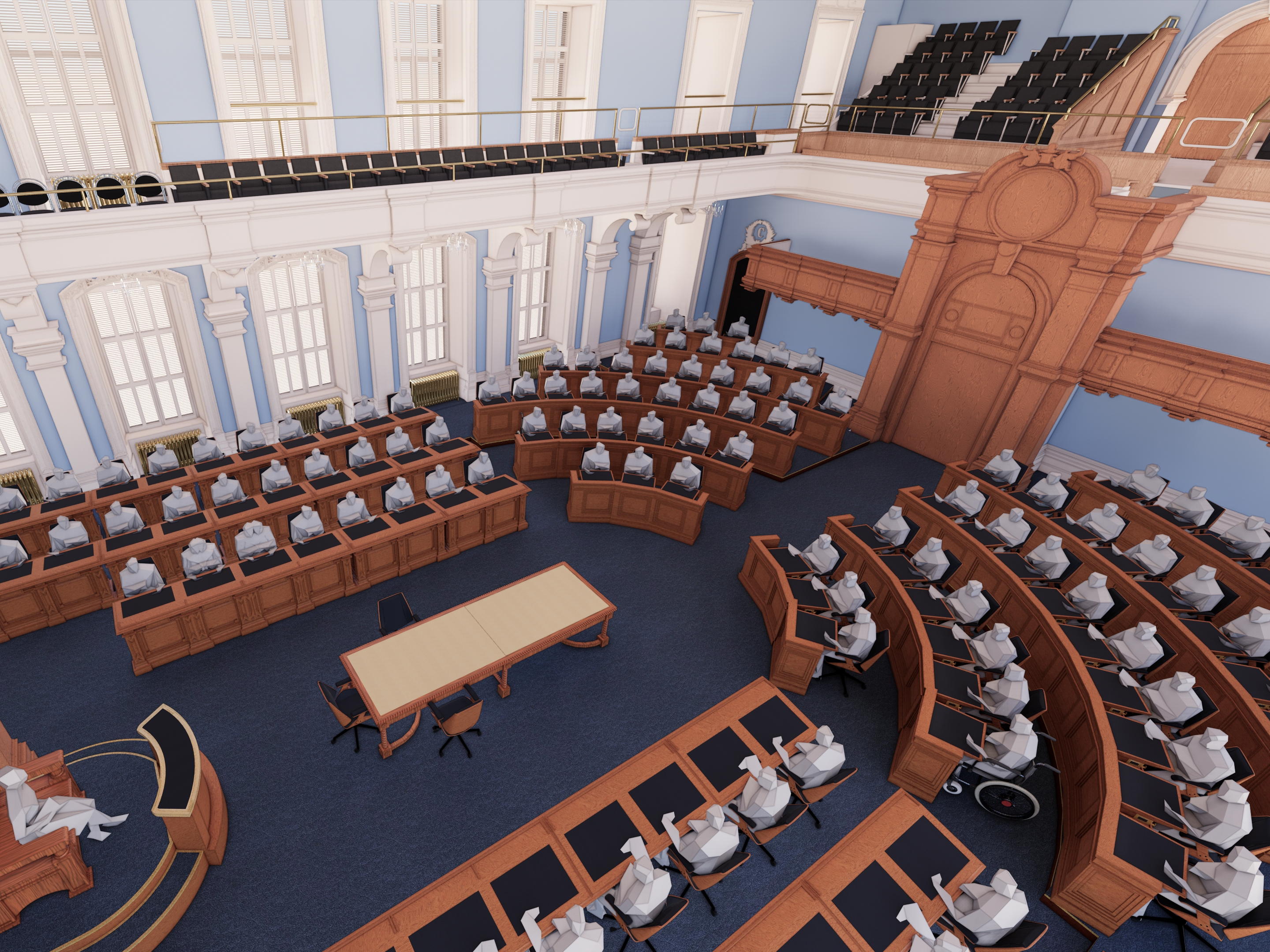

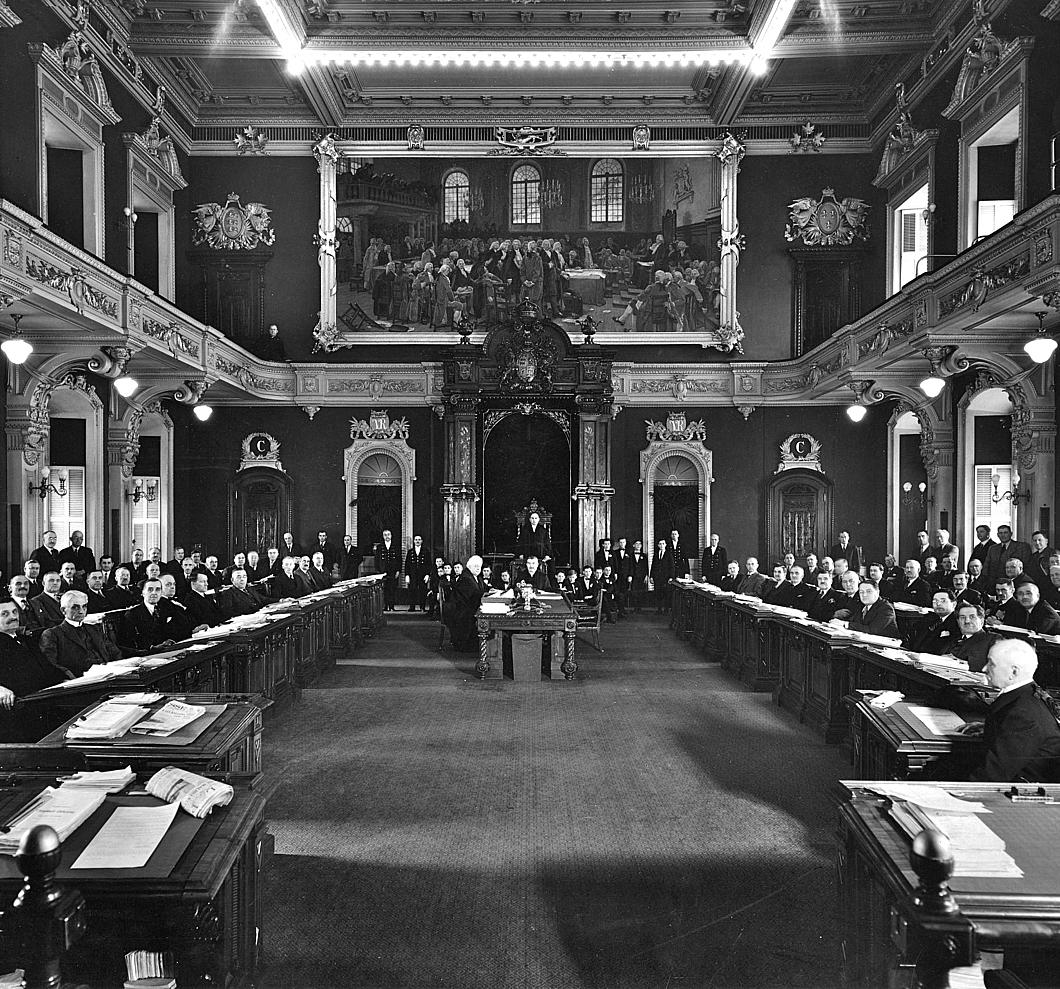

Horseshoe for Quebec’s Salon bleu

Refit will change seating plan in Quebec’s parliament chamber

An upcoming renovation to the Hôtel du parlement in Quebec City will also bring a change in the seating plan of the Assembly’s parliamentary chamber. Deputés agreed a moderate alteration to the current Westminster-style seating plan: a horseshoe shape will replace the crowded back two rows of desks with a curved arrangement.

The original clerks’ table designed by the building’s architect, Eugène-Étienne Taché, in 1886 will also be returned to centre-stage in the Salon bleu (formerly the Salon vert) of Quebec’s National Assembly. The room is also, I believe, the only parliamentary chamber to feature in a film by Alfred Hitchcock.

Renovations are scheduled to begin in January of next year, when deputés will start convening in the Salon rouge that formerly housed Quebec’s Legislative Council, abolished in 1968. (Quebec was the last Canadian province to abolish the upper house of its parliament.)

“The Salon bleu has a strong symbolic value for the Quebec nation,” claims Éric Montigny, professor of political science at Laval University (founded 1663).

“We must respect this tradition and evolve in a very, very gradual manner,” Professor Montigny told the Journal de Québec. “A parliament is not trivial.”

The Assembly numbered only sixty-five members when Taché’s edifice was completed in 1886, while today 125 deputés have to fit into the parliamentary chamber.

The new arrangement would make room for as many as 130 legislators, plus the Président in the speaker’s chair. It will also allow for a good number of the historic desks in the chamber to be retained.

Other potential arrangements were considered and rejected, including introducing a half-moon hemicycle akin to Paris, Washington, and other republican legislatures.

Prof Montigny dismissed claims that semicircular arrangements lead to more collaborative dialogue and constructive work between government and opposition parties:

“It’s an argument that is raised regularly, but I don’t know of any studies that will support this theory.”

The most significant change to the chamber in recent years was the removal of the crucifix from above the président’s chair, first installed in 1936 by the giant of Quebec politics, premier Maurice Duplessis.

That crucifix, and its 1982 replacement, were removed in 2019 and are now displayed as historical artefacts in an ancillary part of the parliament building.

[NDLR: I wrote about the crucifix back in 2008.]

The horseshoe seating plan seems a happy compromise: Westminster-style parliaments — even those that are unicameral like Quebec’s — are honest about the antagonism between government and opposition, and the horseshoe preserves the antiphonal arrangement conducive to this, while rounding it off with a curve at the end.

For my part, I will be happy to see the removal of the arbitrary trapezoid of the modern clerks’ table (below) and its replacement by its historic predecessor.

‘The first great commercial people’

[…]

And it was for this same reason that they were unable to maintain that supremacy: for all its busy tenacity, their effort lacked a higher inspiration and, therefore, real vitality. Numerically, too, they were too few to be able for long to subdue and batten on half the world. It was the same maladjustment which turned Sweden’s taste of world-power into an episode: the national basis was too small.

There is no doubt that the cultural level was at that time higher in Holland than in the rest of Europe. The universities enjoyed an international reputation. Leyden in particular was accounted supreme in philology, political science, and natural philosophy.

It was in Holland that Descartes and Spinoza lived and worked, as also the famous philologists Heinsius and Vossius, the great jurist-philosopher Grotius, and the poet Vondel, whose dramas were imitated all the world over.

The Elzevir dynasty dominated the European book trade, and the Elzevir publications — duodecimo editions of the Bible, the classics, and prominent contemporaries— were appreciated in every library for their elegant beauty and their correctness.

At a time when illiteracy was still almost universal in other lands, nearly everyone in Holland could read and write; and Dutch culture and manners were rated so high that in the higher ranks of society a man’s education was considered incomplete unless he could say that he had been finished off in Holland, “civilisé en Hollande”.

The colonising activities of the Dutch set in practically with the new century, and fill the first two-thirds of it. They quickly gained a footing in all quarters of the world.

On the north-east coast of South America they took possession of Guiana, and in North America they founded the New Amsterdam which was later to become New York: centuries afterwards the Dutch or “Knickerbocker” families still constituted a sort of aristocracy.

They spread themselves over the southern-most tip of Africa, where they became known as Boers, and imported from there the excellent Cape wines.

One whole continent bore their name: namely, New Holland — the later Australia — round which Tasman was the first to sail. Tasman did not, however, penetrate to the interior, but supposed Tasmania (which was named after him) to be a peninsula.

The Dutch were also the first to land on the southern extremity of America, which was named Cape Horn (Hoorn) after the birthplace of the discoverer.

Their greatest acquisitions, however, were in the Sunda islands: Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Celebes, and the Moluccas all came into their possession.

Extending out to Ceylon and Further India, by 1610 they had already founded their main base, Batavia, with its magnificent trade-buildings. In fact they ruled over the whole Indian archipelago. For a time they even held Brazil.

With all this, they never, in the true sense of the word, colonised, but merely set up trading centres, peripheral depots, with forts and factories, intended only for the economic exploitation of the country and the protection of the sea routes.

Nowhere did they succeed in making real conquests; for these, as we said before, they had not the necessary population, nor had they, as a purely commercial people, the smallest interest in doing so.

Their chief exports were costly spices, rice, and tea. To the last-named Europe accustomed itself but slowly. At the English Court it first appeared in 1664 and was not considered very palatable — for it was served as a vegetable. In France it was known a generation earlier, but even there it had to make its way slowly through a mountain of prejudice.

Moreover, its consumption was limited by the Dutch themselves, who, having a monopoly to export it, raised the prices to the level of sheer extortion. This was in fact their normal procedure throughout, and they did not shrink from the most infamous practices, such as the burning of large pepper and nutmeg nurseries and the sinking of whole cargoes.

Their home production, too, dominated the European market with its numerous specialities. All the world bought their clay pipes; a fishing fleet of more than two thousand vessels supplied the whole of Europe with herrings; and from Delft, the main seal of the china industry, the popular blue and white glazed jugs, dishes, and table implements, tiles, stoves, and fancy figures went forth to all points of the compass.

One Dutch article that was in universal demand was the tulip bulb. It became a sport and a science to breed this gorgeous flower in ever new colours, forms, and patterns. Immense tulip farms covered the ground in Holland, and amateurs or speculators would pay the price of an estate for a single rare fancy breed.

The get-rich-quick people threw themselves into the “option” game: that is, they sold costly specimens, which often existed only in imagination, against future delivery, paying only the difference between the agreed price and the price quoted on settling day. It is indeed the Dutch who may claim the dubious honour of having invented the modem stock-exchange system with all the manipulative practices that we know today.

The great tulip crash of 1637, which was the result of all this bubble trading, is the first stock-exchange collapse in the history of the world. The shares of the Dutch trading companies, in particular the East Indian (floated in 1602) and the West Indian (1621), were the first stocks to be handled in the stock-broking manner (their par value speedily tripled itself, and the dividends rose to twenty per cent and higher); and the Amsterdam Exchange, which ruled the world, became the finishing school for the game of “bull” and “bear.”

Then, too, during the first half of the seventeenth century, the Dutch were Europe’s sole middlemen: their mercantile marine was three times as big as that of all other countries.

And although — or indeed because — the whole world depended on it, there arose a bitter hatred against it (contrasting strangely with the extravagant admiration accorded to their manners and comforts) which was intensified by the brutal and reckless extremes to which they went in maintaining their advantage. “Trade must be free everywhere, up to the gates of hell,” was their supreme article of faith.

But by free trade they meant freedom for themselves — in other words, a ruthlessly exploited monopoly. This was also the kind of freedom that Grotius meant when in his famous treatise on international law, Mare liberum, he stated that the discovery of foreign countries does not in itself give right of possession, and that the sea by its very nature is outside all possession and is the property of everyone.

But as the sea was in fact in the possession of the Dutch, this liberal philosophy was no more than the historical mask for an economic terrorism.

In this wise the “United States” became the richest and most prosperous country of Europe. There was so much money that the rate of interest was only two to three per cent.

But although naturally the common people lived under far better conditions than elsewhere, the great profits were made by a comparatively small oligarchy of hard, fat money-bags, the so-called “Regent-families” who were in almost absolute control — since they filled all the leading posts in the government, the judicature, and the colonies — and looked down on the common man, the “Jan Hagel,” as contemptuously as did the aristocrats of other countries.

Opposed to them was the party of the Oranges, who by an unwritten law held the hereditary town governorships; their aim was indeed a legitimate monarchy, but they were nevertheless far more democratic in their ideas than the moneyed class, and were therefore beloved of the people. The best talent, military and technical, gathered about them. The first strategists of the age were on their staff. They nurtured a generation of virtuosi in siege warfare, privateering, artillery, and engineering science. The water-network created by them, which covered the whole of Holland, was considered a world marvel. They were masters, too, of diplomacy. …

St Paul’s: Before and After the War

Wren’s post-Fire St Paul’s Cathedral was an icon of resistance to German aggression and an emblem of survival during the Blitz, but while the dome survived the church did suffer damage: A bomb fell threw the roof of the east end on the evening of 10 October 1940, tumbling masonry and destroying the high altar.

Despite the reredos remaining largely intact, as can be seen in the photograph above, it was decided to remove it and rebuild the High Altar under a baldacchino as Sir Christopher Wren had intended.

In 1958 the new High Altar, designed by W Godfrey Allen and Steven Dykes Bower, was dedicated with an American Memorial Chapel behind it.

This was proposed by the Dean of St Paul’s and General Eisenhower volunteered to raise money for it in the United States.

The Dean turned down the Supreme Commander’s offer, saying that this would be paid for by Britons as an appreciation of the American sacrifice during our common struggle.

A roll of honour lists the names of the 28,000 Americans who gave their lives while stationed from Great Britain.

Perhaps more intriguing than either view is the one below of the interior of St Paul’s before the Victorian scheme for the High Altar was executed.

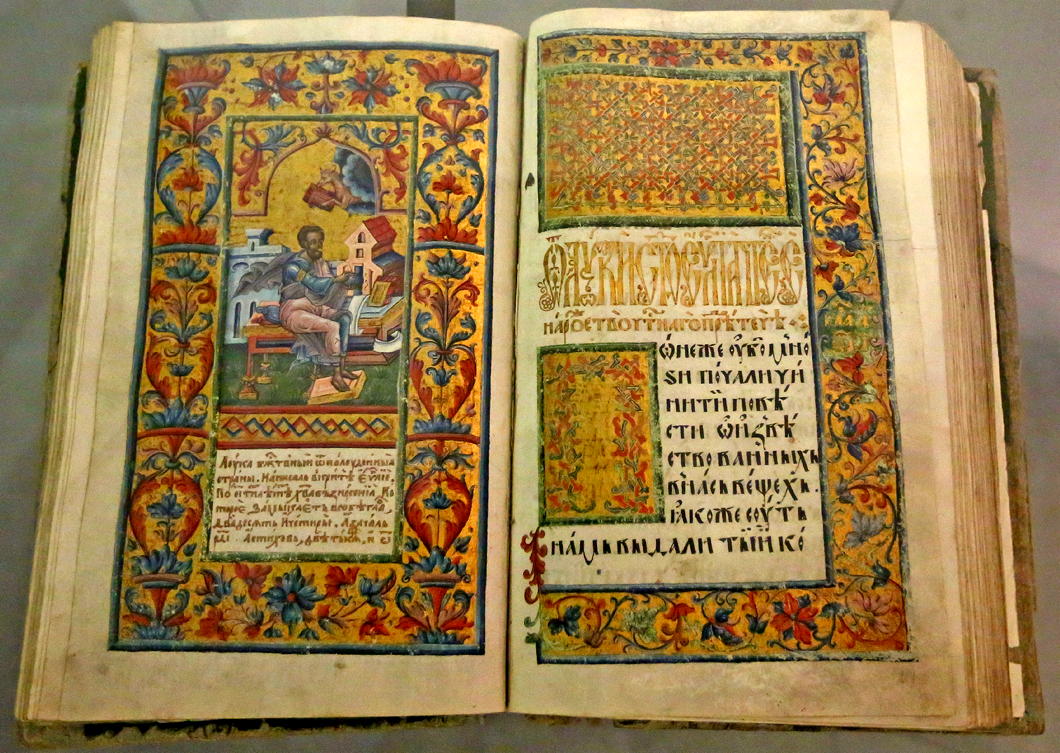

The Ukrainians’ Secret Weapon

For those looking for an explanation as to the notable success of the Ukrainians on the battlefield in the current unpleasantness taking place in their country, look no further.

In a thread of tweets, the biblophile Incunabula reveals the Ukraine’s secret weapon: the Peresopnytsia Gospels (Пересопницьке Євангеліє).

“All six Ukrainian Presidents since 1991,” Incunabula writes, “including Volodymyr Zelensky, have taken the oath of office on this book: the sixteenth-century Peresopnytsia Gospels, one of the most remarkably illuminated of all surviving East Slavic manuscripts.”

“The Peresopnytsia Gospels were written between 15 August 1556 and 29 August 1561, at the Monastery of the Holy Trinity in Iziaslav, and the Monastery of the Mother of God in Peresopnytsia, Volyn.”

“This manuscript is the earliest complete surviving example of a vernacular Old Ukrainian translation of the Gospels. Its richly ornamented miniatures belong to the very highest achievements of the artistic tradition of the Ukrainian and Eastern Slavonic icon school.”

“The Peresopnytsya Gospels were commissioned in 1556 by Princess Nastacia Yuriyivna Zheslavska-Holshanska of Volyn, and her daughter and her son-in-law, Yevdokiya and Ivan Fedorovych Czartoryski. After its completion the book was kept in the Peresopnytsya Monastery.” (more…)

Irving’s Sunnyside

From the Westchester Herald (as reprinted in the Times of London, 24 April 1835):

On the premises just mentioned there is still standing an old stone house, built in the ancient Dutch style of architecture, during the French war, by Wolfred Acker, and afterwards purchased by Van Tassel, one at least of whose descendants has been immortalized in story by the racy pen of its present gifted proprietor.

It is the identical house at which was assembled the memorable tea-party, described in the legend of Sleepy Hollow, on that disastrous night when the ill-starred Ichabod was rejected by the fair Katrina, and also encountered the fearful companionship of Brom Bones in the character of the headless Hessian.

The characters in this delectable drama are mostly known to our readers; but time, that tells all tales, enables us to add one item more, which is, that the original of the sagacious schoolmaster was not the individual generally considered as such, who still resides in this country, but Jesse Martin, a gentleman who bore the birchen sway at the period of which the legend speaks, and who afterwards removed further up the Hudson, and is since deceased.

The location is a most delightfully secluded spot, eminently suited to the musings and mastery of mind; and it is the design of the proprietor, without changing the style or aspect of the premises, to put them in complete repair, and occupy them as a place of retirement and repose from the business and bustle of the world.

Special Mission to Rome

RELATIONS BETWEEN THE Court of St James’s and the Holy See have evolved in the many centuries since the Henrician usurpation. At times, such as during the Napoleonic unpleasantness, the interests of London and the Vatican were very closely aligned — despite the lack of full formal diplomatic relations. Later in the nineteenth century Lord Odo Russell was assigned to the British legation in Florence but resided at Rome as an unofficial envoy to the Pope.

It wasn’t until 1914 that the United Kingdom sent a formal mission to the Vatican, but this was a unique and un-reciprocated diplomatic endeavour — a full exchange of ambassadors would have to wait until 1982. (Until then, the Pope was represented in London only by an apostolic delegate to the country’s Catholic hierarchy rather than any representative to the Crown and its Government.)

Within a year of the Special Mission to Rome being established, John Duncan Gregory (later appointed CB and CMG) was assigned to it. A diplomat since 1902 who had previously worked in Vienna and Bucharest, he was one of the central figures in the curious ‘Francs Affair’ of 1928, when two British diplomats were believed to have unduly abused their positions to speculate in currency. Despite being cleared of illegality, J.D. Gregory was dismissed from his diplomatic posting — though he was later rehabilitated.

Within a year of the Special Mission to Rome being established, John Duncan Gregory (later appointed CB and CMG) was assigned to it. A diplomat since 1902 who had previously worked in Vienna and Bucharest, he was one of the central figures in the curious ‘Francs Affair’ of 1928, when two British diplomats were believed to have unduly abused their positions to speculate in currency. Despite being cleared of illegality, J.D. Gregory was dismissed from his diplomatic posting — though he was later rehabilitated.

If there are any enthusiasts of the curious subcategory of accoutrement known as the despatch box, J.D. Gregory’s one dating from his time in Rome is currently up for sale from the antiques dealer Gerald Mathias.

It was manufactured by John Peck & Son of Nelson Square, Blackfriars, Southwark — not very far at all from me as it happens. (more…)

175 Years of St George’s Cathedral

ONE HUNDRED AND SEVENTY-FIVE years ago, at a time of great uncertainty in Europe, St George’s in Southwark was opened solemnly by Bishop Wiseman — writes the Cathedral Archivist Melanie Bunch. The ceremony was attended by thirteen other bishops in all their finery, of whom four were foreign. Hundreds of clergy of all ranks were in the procession and many of the Catholic aristocracy of England were present. The music was magnificent, the choir including professional singers.

Pugin’s neo-Gothic church was impressive but not finished, and it was not to be a cathedral for another four years. Dr Wiseman, who was both the chief celebrant and the preacher, was bishop of a titular see, as the Catholic dioceses of England and Wales did not yet exist. Nonetheless the opening marked a significant stage in the revival of the Catholic Church in this region. The spur had been the spiritual needs of the poor Irish who had long formed settled communities in parts of London and other cities. The plans for the church had been drawn up in 1839 – before the severity of the famine in Ireland, which began in 1845, could have been foreseen. Some had considered the size of the new church unnecessary, but it turned out to be providential, as immigration from Ireland to this locality and elsewhere was reaching a peak at this time.

The extraordinary turmoil in Europe that had started early in the year in Sicily could not be ignored. In February Louis-Philippe was dethroned in France. There was anxiety that revolution might cross the Channel. Pugin decided that he should obtain muskets to defend his church of St Augustine under construction in Ramsgate. Revolution spread to German and Italian states and countries under Austrian rule. For four days in late June, there was a brief and bloody civil uprising in Paris.

While Europe was ablaze, London was calm, and the opening went ahead. In his homily, Wiseman praised God for all his mercies to this country. From our perspective, we might have expected that he would have spoken about the dark days of persecution, or at least the struggles of the recent past to get such a large church built, constantly hampered by lack of funds. Rev. Dr Thomas Doyle, whom we honour as the founder of the Cathedral, was present and assisting at the Mass, but his courage, faith, and dogged persistence over many years were not acknowledged on this occasion.

We might remember that a Catholic event like this had not been witnessed in England since the Reformation, seemingly prompting Wiseman to take the opportunity to explain to the non-Catholics present that the ceremony and display of the Catholic Church came from a desire to show greater respect for God. To the foreign bishops he said that their presence proved the unity and diversity of the Church. At the end of his homily, Wiseman caused a sensation by reading out a letter from the Archbishop of Paris, Mgr Affre, regretting that he could not attend the opening. By then it was known that he had already died from wounds received on the barricades while he was trying to mediate with the rebels. Wiseman called him a martyr.

Among others who never saw the opening are some who served St George’s mission with Thomas Doyle at the earlier chapel in London Road. Three of them had died before their time, only a few years before, from diseases endemic among their flock. We remember them and all who have served the Cathedral with gratitude. At the time of the opening, St George’s was the largest Catholic church in London, and for the next fifty years was to be the centre of Catholic life in the metropolis. Much has changed since, including the rebuilding of the Cathedral, but we give thanks to Almighty God who continues to sustain it. (more…)

Sibiu/Hermannstadt

SIBIU’s name comes from a Bulgar-Turkic root word meaning “rejoice”, and having spent a few days in the city I can see why. It is handsome, clean, and clearly well looked after — perhaps well loved is the better term.

Unsurprisingly, the mayor partly responsible for this state of affairs was much vaunted for his efforts, to the extent that the Romanians elected him president of the entire country (and this despite him being an ethnic German).

As in all of Transylvania, there is a long history of mixture here, and while the past hundred years have seen a massive collapse in the Hungarian, German, and Jewish populations, many of them persevere all the same, sometimes even flourishing.

Hungarians are the largest and most visible minority in Transylvania — once the dominant people of this province of the Crown of St Stephen — but here in Sibiu they play second-fiddle to the Germans.

Arriving in the Church of the Holy Trinity in the great square for the Hungarian Mass on Sunday, the congregation at the Mass in German preceding it was still filtering away and clearly is the main event of the parish.

The Germans — or Saxons as they are often known — are today under two per cent of the city’s population but, as elsewhere, the Teutonic reputation for competence and efficiency means that a great many ethnic Romanians vote for the Germans’ party, the Democratic Forum of Germans in Romania.

When mayor Klaus Iohannis was elected to the Romanian presidency, he was succeeded as mayor by another member of the German community, the rather elegant Astrid Fodor.

But what of the ethnic Romanians that today make up ninety-five per cent of Sibiu’s townfolk? They are anything but ethnic chauvinists, and seem keen to preserve the traditions of the city and the province, and especially to highlight Sibiu’s distinctiveness. Those I had the pleasure of interacting with were effortlessly warm, courteous, and inviting. Their language is alluringly if mistakenly familiar.

Curiously, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg maintains a consulate here in Sibiu / Hermannstadt with the ostensible excuse that the former German dialect of the town is a close relative of Luxemburgish. The connection bore fruit when Sibiu and Luxembourg City shared the honour of being European City of Culture in 2007.

It was around that time that Forbes magazine rated Sibiu as the seventh most idyllic place to live in Europe — ahead of Rome and just behind Budapest. While such ratings are always arbitrary, I can’t help but share their desire to praise this felicitous city. (more…)

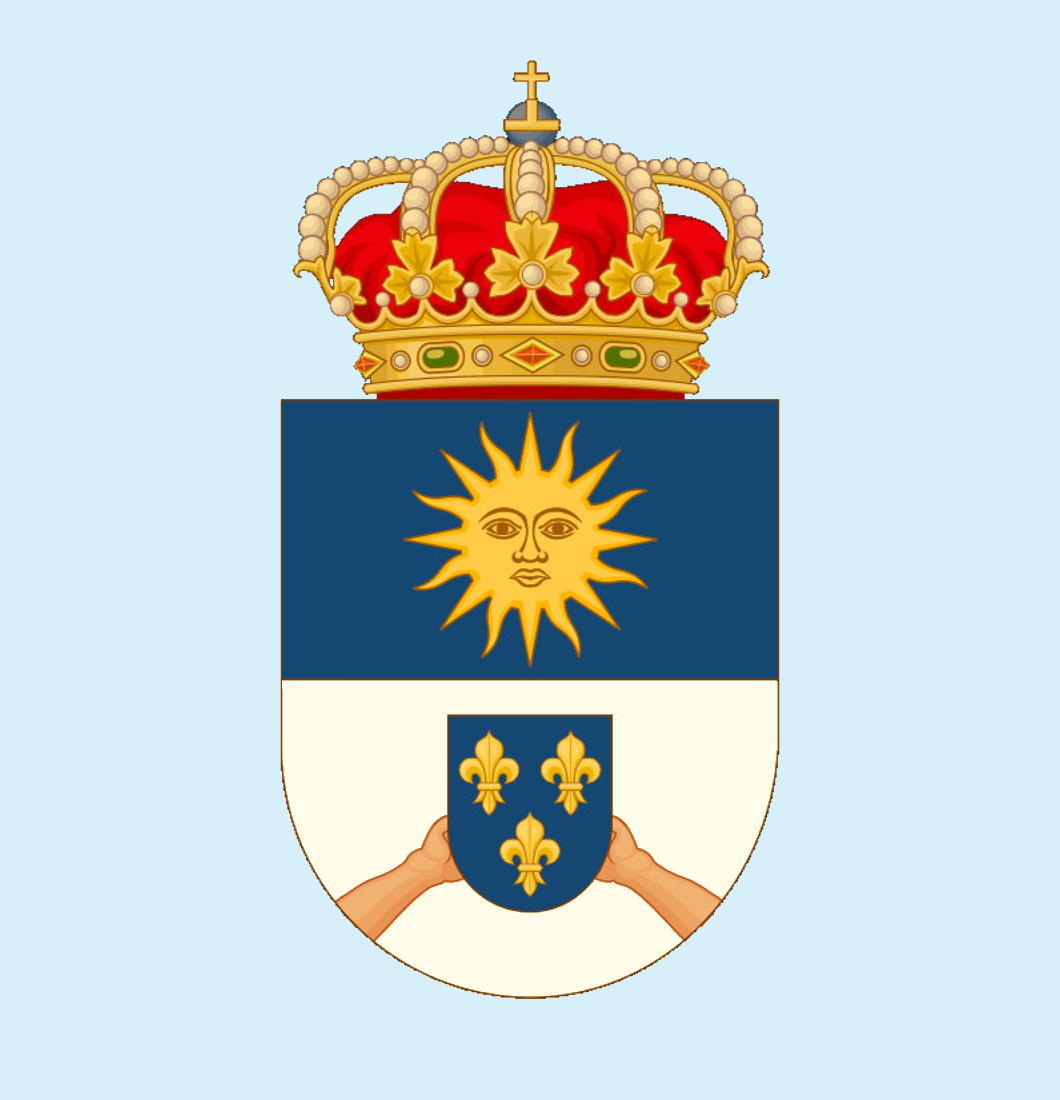

A Realm That Never Was

The United Kingdom of the Rio de la Plata, Chile, and Peru

If we give in to temptation and attempt to see things without the benefit of hindsight, Brazil’s path to independence as a monarchy is less surprising than the fact that Argentina didn’t pursue a similar trajectory. After all: Argentina’s ‘Liberator’, José de San Martín, was himself a monarchist, as was Manuel Belgrano.

Belgrano’s project was to unite the Provinces of the River Plate with Chile and the old viceroyalty of Peru in one united kingdom under a Borbón king. This was to be the Infante Don Francisco de Paula, the youngest son of Charles IV of Spain, but the Spanish king ardently refused to yield his throne’s sovereignty over the new world, nor to allow any of his offspring to take part in the various projects for local monarchies.

When that failed, Belgrano proposed to the Congress of Tucumán that they crown an Incan as king. San Martín, Güemes, and others supported this, but Buenos Aires resisted the plan. They proposed instead to crown Don Sebastián, a Spanish prince living in Rio de Janeiro with his maternal grandfather, King João VI of Portugal.

João thought the scheme would end up injurious to Portugal’s interests and so put the kibosh on it.

And don’t get us started on Carlotism, which was a whole ’nother pile of tricks.

Belgrano’s monarchic project in its 1815 iteration was to unite the provinces of the River Plate with Chile and the old viceroyalty of Peru to create a single realm out of these Spanish-speaking territories.

He even drafted a constitution for the United Kingdom of the Rio de la Plata, Chile, and Peru, which is rudimentarily translated into English below. This even went so far as to specify the coat of arms and flag of the kingdom.

The best history covering these unconsummated plans remains Bernado Lozier Almazán’s 2011 book Proyectos monárquicos en el Río de la Plata 1808-1825: Los reyes que no fueron which sadly has not yet been translated into English.

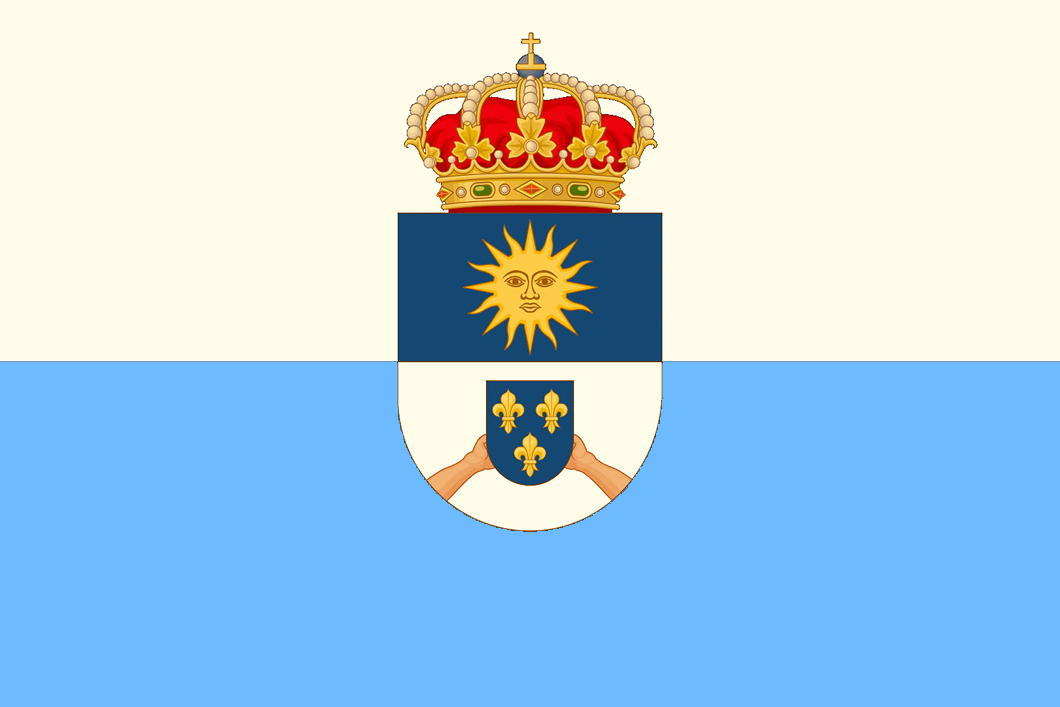

Article 1 — The new Monarchy of South America will have the name of the United Kingdom of the Río de la Plata, Peru, and Chile; its coat of arms will be a shield that will be divided into blue and silver fields; In the blue that will occupy the upper part, the image of the Sun will be placed, and in Silver two arms with their hands that will hold the three flowers of the emblems of My Royal Family; surmounted by the Royal Crown, and will have as supporters a tiger and a llama. Its flag will be white and light blue.

Article 2 — The Crown will be hereditary in order of proximity in the lines of agnation and cognation.

Article 3 — If, God forbid, the current King dies without succession, his rights will revert to me so that with the agreement and consent of the Legislative Body I choose another Sovereign from my Royal Family; but, if I no longer exist, said Chambers will have the power to elect one of the princes of my Blood Royal as their King.

Article 4 — The person of the King is inviolable and sacred. The Ministers are responsible to him. The King will command the forces of sea and land; he will declare war, he will make peace; he will make treaties of alliance and trade; he will distribute all the offices, he will be in charge of the public administration, the execution of the laws, and the security of the State to whose objects he will give the necessary orders and regulations.

Article 5 — The King will name all the nobility; he will grant all the dignities, he will be able to vary them and grant them for life, or make them hereditary. The King may forgive offences, commute sentences, or dispense them in the cases that the law grants him.

Article 6 — The nobility will be hereditary in the same terms as the Crown; it will be distinguished precisely in three grades, and cannot be extended to more: the first grade will be that of Duke, the second of Count and the third of Marquis; the nobles will be judged by only those of their class, they will have part in the formation of the laws, they will be able to be Deputies of the Towns and they will enjoy the honours and privileges that the law or the King grants them; but they may not be exempted from the charges and services of the State. Any individual of the State of any class and condition may opt for the nobility for their services, for their talents, or for their virtues. The first number of the nobility will be agreed by the King and Representative and at any other time by the Legislative Body.

The Legislative Body

Article 7 — The Legislative Body will be composed of the King, the Nobility, and Representation of the Commons.

The Upper Chamber will be formed: the first part by all the Dukes, whose right is declared inseparable from their dignity; the third part of the Counts, by election among themselves, presided over by a King’s Commissioner; the fourth part of the Marquises, elected on their own terms; and the fifth part of the Bishops of the Kingdom, elected the first time by the King, being in charge of it and the other Chamber, to establish the bases for the election of this body for the future.

Article 8 — The Second Chamber will be made up of the Deputies of the Peoples, who will be elected for the first time in the customary terms that allow less play to the parties, and will consult the greatest opinion, it being an essential charge to the Legislative Body to establish for the latter the most adequate and precise laws.

Article 9 — The power to propose the law will be common to the King and both Chambers; the order of the proposition will be from the King to the First Chamber, and from this to the King, and from the Second to the First, in the event that a proposal is not admitted by its immediate chamber, it cannot go to the third, nor be repeated until another session. Every law will be the result of the plurality of both Chambers, and secondly of the King; the sanction and promulgation of the law will be exclusively his.

The chambers may not join or dissolve without the express order of the King. He will be able to extend them for as long as he deems it necessary, and dissolve that of the Deputies when he deems it appropriate.

Article 10 — The designation of the King’s income, his Royal House and Family, the expenses of his Minister and Cabinet, the civil list, the military, and extraordinary expenses will be exclusively agreed by both Chambers, to which in the same way belongs to the arrangement and imposition of rights and contributions.

The Ministry

Article 11 — No order of the King without the authorisation of his corresponding Minister will be fulfilled; the Ministers will have the power to propose to both Chambers what they deem appropriate, and enter any of them to report what they deem appropriate; the Ministers will indispensably be Members of the High Court, and only by it may they be judged. The Ministers may not be accused except for treason or extortion, the accusation will not be admissible unless it is made by the plurality of one or another Chamber; the Minister of Finance will present to both Chambers for their knowledge and approval the accounts of the previous year.

The Judiciary

Article 12 — The judges will be appointed by the King; they will be perpetual and independent in their administration, only in the case of notorious injustice or ruling can they be accused before the Upper Chamber who will judge them independently of the King, who will protect and execute their decisions in this part; The judges of the fact will be established, called the jury in the most adaptable way to the situation of the Towns.

The Commonalty of the Nation

Article 13 — In addition to the proportionate and uniform distribution of all charges and services of the State, the option to nobility, jobs and dignities, and the common competition and subjection to the law; The Nation will enjoy, with the inalienable right to property, freedom of worship and conscience, freedom of the press, the inviolability of property, and individual security in the terms clearly and precisely agreed upon by the Legislative Power.

Those elected by the nobility, clergy, and commonalty will last six years, starting to renew the first elected by half every three years: The Common Deputies may not be executed, persecuted, or tried during their commission, except in cases that the law designated and by the Chamber itself to which they belong.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories