Tradition

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Emperor in British Columbia

The Emperor & Empress of Japan in the Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, on a recent visit to British Columbia.

Leve de Koningin!

“Hoera! Hoera! Hoera!” — The Third Tuesday in September Beholds the State Opening of the States-General of the Netherlands

Previously: Prinsjesdag

St. Nicholas of the Seven Seas

ONE OF OUR correspondents sends word that Russia is to name the fourth of her Borei-class ballistic missile submarines Николай Чудотворец, which is to say “Saint Nicholas”. The Borei-class vessels are the first series of Russian strategic submarines to be launched in the post-Soviet era. The previous subs in the class have been named the Yuri Dolgoruki (after Prince Yuri I, founder of Moscow), the Alexander Nevsky (after the Grand Prince of Vladimir & Novgorod venerated as a saint in the Eastern churches), and the Vladimir Monomakh (after the Grand Prince of Kievan Rus). The Saint Nicholas is of course not the first boat or ship to bear the name of New York’s patron saint. There was HMS St. Nicholas as well as a Spanish naval ship San Nicolas in the 1790s, eventually captured by the Royal Navy and commissioned as HMS San Nicolas. A Sealink (later Stena) ferry named St. Nicholas traversed the Harwich/Hook-of-Holland route from 1983 until it was renamed Stena Normandy in 1991 and transferred to the Southampton/Cherbourg route. Numerous merchant vessels took the saint’s name and patronage throughout the nineteenth century.

ONE OF OUR correspondents sends word that Russia is to name the fourth of her Borei-class ballistic missile submarines Николай Чудотворец, which is to say “Saint Nicholas”. The Borei-class vessels are the first series of Russian strategic submarines to be launched in the post-Soviet era. The previous subs in the class have been named the Yuri Dolgoruki (after Prince Yuri I, founder of Moscow), the Alexander Nevsky (after the Grand Prince of Vladimir & Novgorod venerated as a saint in the Eastern churches), and the Vladimir Monomakh (after the Grand Prince of Kievan Rus). The Saint Nicholas is of course not the first boat or ship to bear the name of New York’s patron saint. There was HMS St. Nicholas as well as a Spanish naval ship San Nicolas in the 1790s, eventually captured by the Royal Navy and commissioned as HMS San Nicolas. A Sealink (later Stena) ferry named St. Nicholas traversed the Harwich/Hook-of-Holland route from 1983 until it was renamed Stena Normandy in 1991 and transferred to the Southampton/Cherbourg route. Numerous merchant vessels took the saint’s name and patronage throughout the nineteenth century.

Beers We Have Known (and Loved)

“What’s your favourite beer?” one might very well ask, but it’s a difficult question to answer. Like wines, there are different beers for different occasions and what might be perfect for one situation might prove inappropriate in others. I loathe the disgusting lagers that the word “beer” represents for most Americans. I prefer the middle-to-darker range of beers, and a good bitter in the afternoon is heavenly.

Old Speckled Hen is one of my favourites, and I’ve found it goes very well with ham.

Lunch today was a perfect croque-monsieur & salad with side of Belgian fries at one of my preferred Manhattan eateries, served with a glass of De Koninck.

Leffe, in its blonde and brown varieties, is appropriate on most occasions.

Chimay is great for a winter’s evening by the fire, if there’s no mulled wine available.

John Smith’s was our favourite tipple at university, where the Russell sold it in two-pint glasses until they realised my circle were the only ones drinking it and so replaced it with something more profitable.

Boddingtons is similar to John Smith’s and more readily available in the States.

My favourite beer, however, is actually made by the Prince of Wales (of all people): the organic ale produced by the Duchy of Cornwall. (The ancient duchy is among the many titles traditionally held by the Sovereign’s heir, and the one immediately following Prince of Wales in precedence). To my continual surprise, I’m able to find it for purchase right in my home town. I wonder if they keg it for draught as well, though surely that would be impossible to find in America.

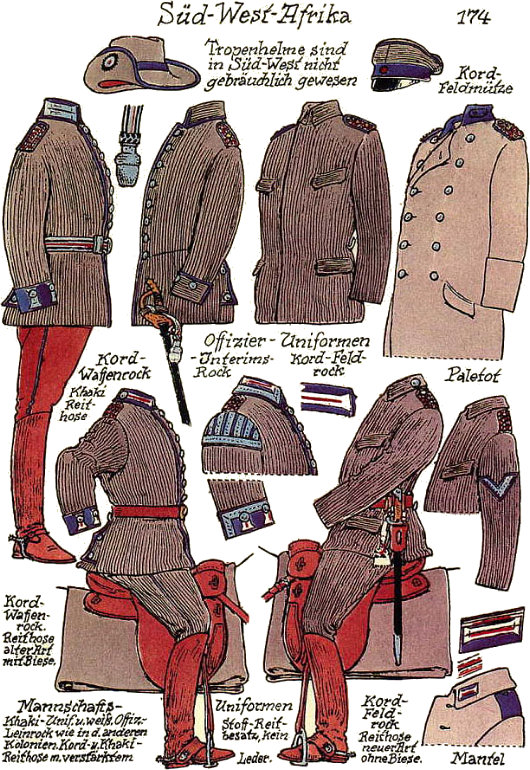

The Union Defence Force

From 1912 to 1957, South Africa’s military was called the Union Defence Force (the Union in question being the Union of South Africa, the other USA). The Nationalist government renamed it the South African Defence Force (Suid-Afrikaanse Weermag) in 1957, prior to the declaration of the Republic of South Africa in 1961. After the introduction of universal suffrage in 1994, the SADF was merged with the MK (Umkhonto we Sizwe, the ANC’s terror branch) and APLA (Azanian People’s Liberation Army, the terrorist wing of the Pan-Africanist Congress), as well as the Self-Protection Units of Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi’s Inkatha Freedom Party, into the South African National Defense Force (SANDF, or SANDEF), which remains the name of the country’s armed forces today.

Reclaiming his Birthright

Blessed Emperor Charles’s two homecomings to Hungary after the overthrow of the Hapsburgs are worthy of the greatest spy novels, except they are fact: the hushed secrecy and underground preparations, the airplane contracted under a false name, the disguises used to sneak over borders. In his first attempt, Charles — the Apostolic King of Hungary — made it all the way to Budapest, only to be persuaded to return to exile by the self-appointed regent, Admiral Horthy (a naval commander in what, by then, was a land-locked country).

The King’s second attempt to reclaim his power was much more considered and deliberate, and he spent some time securing a loyal power base of local nobility before pressing on to Budapest by armoured railway train. The King’s force made it to just outside of the Hungarian capital before they were overwhelmed by troops loyal to Horthy — who, in order to maintain their loyalty, neglected to inform the soldiers and officers that the “rebels” they were fighting were actually those of their King and Queen.

Along his path to the capital, the King was greeted by fervent crowds, and stopped at least twice to review small detachments of troops and to show himself in person to his loyal Hungarian subjects. The King had returned, but sadly not for long. After the failure of this second attempt, the Allied powers refused to allow the Imperial & Royal family to remain in mainland Europe, and exiled them to the Portuguese island of Madeira, where the Emperor-King grew ill and eventually died. He is entombed on the island today — a source of great pride, I am told, to the Madeirans.

Elsewhere: Miracle Attributed to Blessed Charles (Norumbega)

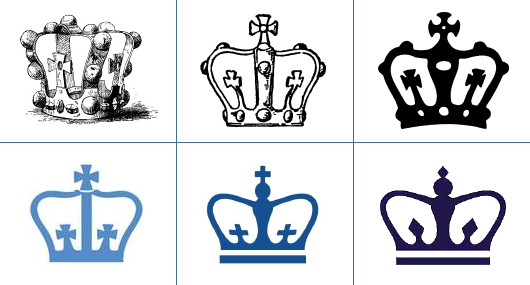

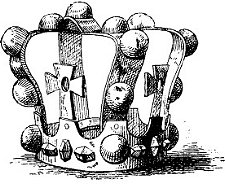

Crosses Return to Columbia Crown

AFTER AN ABSENCE of some years, Columbia University has returned the crosses to its official crown emblem. The crosses had been missing since March 2004, when they were replaced with trapezoidal lozenges, but the more historic cross design has quietly returned to favour as the Ivy League institution’s official symbol. Columbia was founded in 1784, but claims the earlier heritage of King’s College, founded in 1754 but exiled to Nova Scotia, where it now has university status, after the tumult of the American Revolution. A copper crown (right) was originally attached to the cupola of College Hall, King’s College’s home in the colonial city of New York. When Columbia was founded in 1784, a year after New York’s independence was recognized, the state legislature gave the property and endowment of King’s College to the new Columbia College, which was organized by the remaining non-Loyalist members of King’s College. (more…)

AFTER AN ABSENCE of some years, Columbia University has returned the crosses to its official crown emblem. The crosses had been missing since March 2004, when they were replaced with trapezoidal lozenges, but the more historic cross design has quietly returned to favour as the Ivy League institution’s official symbol. Columbia was founded in 1784, but claims the earlier heritage of King’s College, founded in 1754 but exiled to Nova Scotia, where it now has university status, after the tumult of the American Revolution. A copper crown (right) was originally attached to the cupola of College Hall, King’s College’s home in the colonial city of New York. When Columbia was founded in 1784, a year after New York’s independence was recognized, the state legislature gave the property and endowment of King’s College to the new Columbia College, which was organized by the remaining non-Loyalist members of King’s College. (more…)

Flammen & Citronen

IT’S NOT VERY OFTEN that a big-budget period film comes out of Scandinavia, but recently there’ve been not one, but two. Here mentioned is the Danish film “Flammen & Citronen”, an action-drama based on the Second World War actions of Bent Faurschou-Hviid (nicknamed “Flame”) and Jørgen Haagen Schmith (“Citron”). Faurschou-Hviid and Schmith were members of the Holder Danske group, a Danish resistance organization primarily composed of Danes who had previously fought for Finland against the Soviet Union in the Winter War of 1939-1940. (more…)

Celebrating a Great Scot: David Lumsden

I can’t tell you how often I come across something and think to myself “I must ask Lumsden about that”, and then suddenly realise that no such thing is possible anymore. I only had the privilege of knowing this gentle giant of a man towards the end of his life, but am grateful even for that relatively short friendship. Below is the address given by Hugh Macpherson at the Thanksgiving Service for the Life of David Lumsden of Cushnie that took place at St. Mary’s Church, Cadogan St., London on Monday, 27th April 2009. May he rest in peace.

It is difficult to mark the passing of such a remarkable personality as David Lumsden. We have done with the requiems and the pibrochs and must now look forward to celebrate an extraordinary life lived to the full.

It is difficult to mark the passing of such a remarkable personality as David Lumsden. We have done with the requiems and the pibrochs and must now look forward to celebrate an extraordinary life lived to the full.

David was a man of many parts and passions. He was a renaissance man with a wide variety of interests, and if he did not know the answer to any particular question, he certainly knew where to look it up, and in a few days there would be an informative card in the post. He had a lively curiosity and sense of adventure.

Perhaps the ruling passion in his younger life was that of rowing. He rowed at Bedford School and when he went up to Jesus College Cambridge, he joined the boat club, eventually becoming Captain of Boats. There were, I think, eventually eight “oars” on the walls of his various houses. I think that David was one of the few people I know who went to Henley to actually watch the racing, and when one went into the trophy tent his name could be found on some of the trophys. The expedition to Henley was one of the fixed points of David’s year.

He travelled round the country rather like the “progress” of a monarch of old. This progress encompassed the Boat Race, Henley, the Royal Stuart Society Dinner, the Russian Ball, spring and autumn trips to Egypt, the Aboyne Games, the 1745 Commemoration, the Edinburgh Festival, and numerous balls and dinners, including of course the Sublime Society of Beef Steaks.

Rather like clubs, David and I had a “reciprocal” arrangement: When I was in Scotland I lodged with him, and when he was in London he lodged with me, and I can tell you that there were many times when I simply could not keep up with his social whirl, in fact once or twice I distinctly fell off! I remember one particularly splendid and bibulous dinner at the House of Lords at which we were decked in evening dress and clanking with all sorts of nonsense — after many attempts to hail a taxi, David turned and said to me “You know we are so drunk they won’t pick us up. We’ll have to stagger back.” And so we wound a very unsteady path back to Pimlico, shedding the odd miniature en route.

At Cambridge, David also formed a lasting friendship with Mgr. Alfred Gilbey, Catholic Chaplain to the University, who was to have a lasting influence on David’s faith and life, and, I think, introducing him to the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, where he eventually became a Knight of Honour & Devotion.

David’s faith was an important part of his life. When he was in London he would attend this church on a Sunday morning to hear the 11.30 Latin Mass, which finished conveniently near to the opening time at one of his favourite watering holes in the Kings Road. (more…)

The Principality of South Africa

“… or some such thing.”

History has shown that good ideas often come from the humblest of sources. One such example, though regrettably one of a suggestion not put into practice, was a proposal submitted by D. M. Perceval, the humble clerk of the Advisory Council of the Cape of Good Hope colony in 1827 to his higher-ups in the Colonial Office in London. Perceval wrote to request an official seal for the British colony at the end of Africa, but he went a step further with his fairly normal request, extraordinarily suggesting that “the opportunity might be taken to erect [the Cape of Good Hope] into the Principality of South Africa, or some such thing, for the present name is really too absurd for the whole country.”

The title “Prince of South Africa” would have been part of the British Crown, and presumably available as a courtesy title for offspring, just as the eldest son is often (such as now) created Prince of Wales. Would the second son then be “Prince of South Africa”, or would the title stay with the Sovereign? “By the grace of God, King of Great Britain & Ireland, Emperor of India, Prince of South Africa, &c.” It does have a nice ring to it. (more…)

Seanad Éireann

Ireland’s senate is a curious creature. Its first members were co-opted & appointed and these included seven peers, a dowager countess, and five baronets and knights, twenty-three Protestants, and a Jew. Among this cast of characters were W. B. Yeats, General Sir Bryan Mahon, and the physician-poet-author Oliver St. John Gogarty. In 1937, however, the Seanad Éireann took its current form, and since the abolition of the Bavarian upper house in 1999, the Seanad is (so far as my research can discover) the last corporately organised parliamentary body in Europe.

There are sixty members of the Irish senate, who are chosen by a variety of means. (more…)

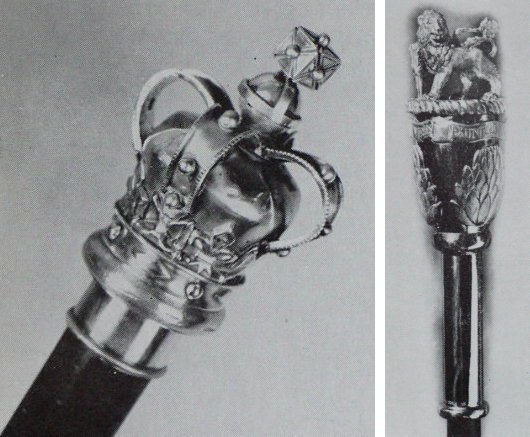

Black Rod — Swart Roede

In my post on the 1947 Royal Visit to Cape Town, I mentioned just in passing the title of the Draer van Swart Roede — or the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, as he is known in English. Well, here is the Black Rod itself. The original South African Black Rod (left) dates from the Parliament of the Cape of Good Hope and was adopted as the Black Rod of the Union Parliament when South Africa was unified in 1910. After the abolition of the monarchy in 1961, a new Black Rod (right) was commissioned which featured protea flowers topped with the Lion crest from the South African coat of arms.

Black Rod (the person, not the staff) was the Senate’s equivalent of the House of Assembly’s sergeant-at-arms (ampswag). The first Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod in history was appointed in 1350 and the position still exists today in the British Parliament of today. Black Rod is sergeant-of-arms of the House of Lords, as well as Keeper of the Doors. The Usher’s best-known role is having the doors of the House of Commons ceremonially slammed in his face when he acts as the Crown’s messenger during each State Opening of Parliament, a ritual derived from the 1642 attempt of Charles I to arrest five members of parliament.

In South Africa, die Swart Roede traditionally wore wore a black two- or three-pointed cocked hat, a black cut-away tunic, knee breeches, silk stockings and silver-buckled shoes, but this costume of office has undergone a process of modernisation since the 1950s. After the vast expansion of the electorate in 1994 and introduction of an interim constitution, Black Rod’s title was officially shortened to “Usher of the Black Rod” to make it “gender-neutral”. (Regrettably, the Canadian Senate has also mimicked this innovation, though it is often unofficially ignored.) When a new, permanent constitution was enacted in 1997, the Senate was replaced by the National Council of Provinces as the upper house of parliament. A new Black Rod (the staff, not the person) was introduced in 2005, but is of such a garish design that it is best left uncommented upon.

The Band-leader & the Sergeant-Major

I came across these two characters in the Castle in Cape Town, the oldest building in South Africa and still home to the Cape Town Highlanders and Cape Garrison Artillery.

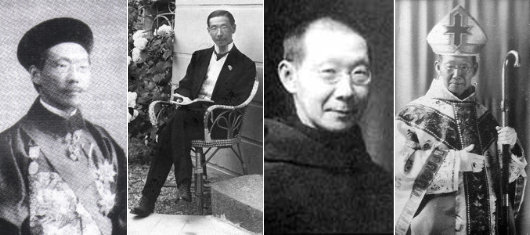

The Prime Minister of China who became a Benedictine Abbot

CHRISTIANITY HAS A LONG and varied history in China stretching over at least one-and-a-half millenia. The ancient country has even had Christian leaders, such as the Congregationalist founder of the Chinese Republic, Sun Yat-sen, and his Methodist successor, Gen. Chiang Kai-shek (head of the Kuomintang for nearly forty years). Still, until I read this fascinating story in the Catholic Herald I had no idea that there was a Prime Minister of China, Lou Tseng-tsiang (陸徵祥), who ended his days as a Benedictine monk by the name of Dom Pierre-Célestin. Lou was born a Protestant in Shanghai in 1871, but married a Belgian woman and eventually converted to Catholicism. Serving his country in the diplomatic arena, he accomplished extensive reforms of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, avoided becoming part of any of the various factions that divided the government, and was one of the founding members of the Chinese Society of International Law. Lou bravely stood up to the indignities imposed upon China through the 1919 Treaty of Versailles by refusing to sign the shameful document which sewed the seeds of future disaster.

Xu Jingcheng, Lou’s mentor and sometime Ambassador to the Court of the Tsars in St. Petersburg, instructed the up-and-coming diplomat that “Europe’s strength is found not in her armaments, nor in her knowledge — it is found in her religion. … Observe the Christian faith. When you have grasped its heart and its strength, take them and give them to China.”

After the death of his wife, Lou became a Benedictine monk at the abbey of Sint-Andries in Flanders, and was eventually ordained a priest in 1935. A decade later, Pope Pius XII — who cared deeply for the Church in China and finally settled the long-standing dispute over Chinese ancestor-honouring rituals in favour of the practices — appointed him titular abbot of the Abbey of St. Peter in Ghent. Sadly, the Chinese Civil War prevented Dom Pierre-Célestin from returning to China, and he died in Flanders in 1949.

The words of Lou’s mentor that Europe’s strength is her faith found recent confirmation from Professor Zhao Xiao, a prominent Chinese economist at the University of Science & Technology Beijing. Prof. Zhao, a member of the Chinese Communist Party, began studying the differences between the economies of Christian societies and those of non-Christian societies. As a result of his investigations, he argued that Christianity would provide a “common moral foundation” for China that would help the economy by reducing corruption, narrowing the gap between rich and poor, preventing pollution, and promoting philanthropy.

“A good business ethic or business morality,” Prof. Zhao says, “can provide for a type of motivation that transcends profit seeking. Why do people want to do business? The main goal would be to earn money. The purpose of a company is to maximize profits. But this can cause companies to look for quick results and nearsighted benefits. It can cause companies to disregard the means and earn money at the expense of destroying the environment, society and the livelihood of others, or endangering the entire competitive environment of the trade.”

“If my motivation for doing business is the glory of God, there is a motivation that transcends profits. I cannot go and use evil methods. If I used some evil methods to enlarge the company, to earn money, then this is not bringing glory to God. Therefore, this is to say that it [bringing glory to God] can provide a transcendent motivation for business. And this kind of transcendental motivation not only benefits an entrepreneur by making his business conduct proper but it can also benefit the entrepreneur’s continued innovation.” (more…)

Heaven in Herefordshire

In the weekly South African edition of the Telegraph, I came across a brief note marking the death of England’s oldest publican, Flossie Lane of ancient Leintwardine in Herefordshire. From the internet, I find the full version of her obituary, which is reproduced below. The Sun Inn, with its “Aldermen of the Red-Brick Bar” sounds like a splendid haven.

Flossie Lane, who died on June 13 aged 94, was reputedly the oldest publican in Britain, and ran one of the last genuine country inns

For 74 years she had kept the tiny Sun Inn, the pub where she was born in the pre-Roman village of Leintwardine on the Shropshire-Herefordshire border.

As the area’s last remaining parlour pub, and one of only a handful left in Britain, the Sun is as resolutely old-fashioned and unreconstructed today as it was in the mid-1930s when she and her brother took it over.

According to beer connoisseurs, Flossie Lane’s parlour pub is one of the last five remaining “Classic Pubs” in England, listed by English Heritage for its historical interest, and the only one with five stars, awarded by the Classic Basic Unspoilt Pubs of Great Britain.

She held a licence to sell only beer – there was no hard liquor – and was only recently persuaded to serve wine as a gesture towards modern drinking habits.

With its wooden trestle tables, pictures of whiskery past locals on the walls, alcoves and a roaring open fire, the Sun is listed in the CAMRA Good Beer Guide as “a pub of outstanding national interest”. Although acclaimed as “a proper pub”, it is actually Flossie Lane’s 18th-century vernacular stone cottage, tucked away in a side road opposite the village fire station.

There is no conventional bar, and no counter. Customers sit on hard wooden benches in her unadorned quarry-tiled front room. Beer – formerly Ansell’s, latterly Hobson’s Best at £2 a pint – is served from barrels on Flossie Lane’s kitchen floor. (more…)

Lord Clark

This clip of Kenneth McKenzie Clark, Baron Clark, OM, CH, KCB, FBA is from the end of his BBC documentary series Civilisation. Here Lord Clark complains about the lack of a true center, as he then could see none. Thankfully, Lord Clark found that center shortly before the end of his life, and was received into the Catholic Church.

“The great achievement of the Catholic Church,” said Lord Clark in Civilisation, “lay in harmonizing, civilising the deepest impulses of ordinary, ignorant people.”

First Things, Three Songs

Through an interesting post by Joseph Bottum on the First Things blog, I discover that R. R. Reno posted all three of the songs I elaborated upon in my June 2007 post “We’ve Lost More Than We’ll Ever Know”, though (so far as I can tell) he arrived at the same three without stumbling across my entry on them. I always read First Things in New York (it’s one of my favourites, and simply a must-read), but it’s sadly not available in South Africa (bar actually scraping one’s pennies together for a subscription) so I’ll just have to wade through friends’ archives when I return to the Empire State. (Or does the Society Library have a subscription? And if not, why not?).

While it has a reputation among some Catholics as being a bit too liberal & democratist, I suspect the whiff of Americanism one finds in the pages of First Things is akin to the aroma of tobacco in an old bar: the smell lingers but that doesn’t mean anyone’s actually still smoking. Nonetheless, they often feature top-notch articles and writing that are of interest to Catholics & other traditionalists.

Of tribes and traditions

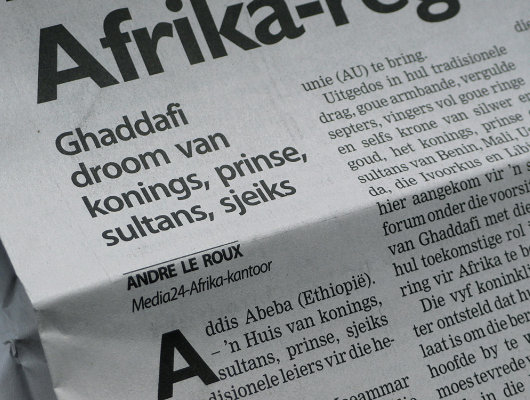

In tribal Africa, Ghaddafi expounds traditional government; Meanwhile ethnic Romanians vote to be ruled by their German neighbours.

«Ghaddafi dreams of kings, princes, sultans, sheiks»

reports the Afrikaans newspaper Die Burger.

ONE OF THE LESS-REPORTED aspects of the selection of Col. Moammar al-Ghaddafi, the tent-dwelling Libyan leader and notorious eccentric, as Chairman of the African Union was his proposal that an upper house of “kings, princes, sultans, sheiks, and other traditional leaders” be added to the Pan-African Parliament. Col. Ghaddafi has been forthright in his condemnation of democracy as ill-suited to the African continent. “We don’t have any political structures [in Africa], our structures are social,” he explained to the press. Africa is essentially tribal, the argument goes, and as such multi-party democracy always develops along tribal lines, which eventually leads to tribal conflict and warfare. “That is what has led to bloodshed,” the AU chairman posited, citing the recent example of the Kenyan elections.

Europe, of course, solved the matter of tribal difficulties by brutally uprooting long-established peoples from their native lands after the Second World War and transferring them to jurisdictions in which they would ostensibly be part, not only of the majority, but of theoretically “national” states. Cities with centuries of Polish history became Soviet, towns as German as sauerkraut became Polish, and so on and so forth. Sometimes the undesired populations of multi-ethnic places were cruelly murdered, as recent revelations from the police in Bohemia have shown.

Still, remnants of the old cosmopolitan order remain. (more…)

A Good Day in Cape Town

The South African Royal Family’s 1947 visit to “Die Moederstad”

SOUTH AFRICA IS a nation that took a long time birthing, from the first steps van Riebeeck took on the sands of Table Bay in 1652, through the tumult of the native wars, the tremendous conflict between Briton & Boer, and ultimately what was hoped would be the final reconciliation in Union of South Africa — 1910. In that year, young Prince Albert of York & of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha was just fifteen years of age, and South Africa became a dominion just weeks after his father became King George V.

Albert was the second son of a second son, so at the time of his birth (and for most of his early life) it was never expected that he would one day be King of Great Britain, Emperor of India. It was his brother’s abdication that thrust poor Bertie, as he was always known to his loved ones, upon the throne imperial. It was a cold December day in 1936 that the heralds of the Court of St. James proclaimed him George VI.

By his nature, the King was a quiet and reserved man, partly because of the stammer that impeded his speech. George VI was happiest among his family, and they accompanied him in 1947 on a long voyage aboard HMS Vanguard, to his far-off kingdom on the other side of the world, where the two oceans meet. It was the first time a reigning monarch has set foot on South African soil, and Capetonians waited in earnest anticipation to see their sovereign. How appropriate that this happy city — moederstad, or “mother-city”, of all South Africa — would be the first to receive him. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories