Tradition

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

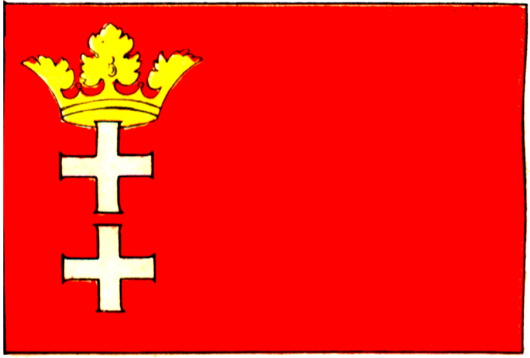

Danzig in Flag & Arms

The first time I met my friend Rafal, I noticed his necktie bedecked with a subtle heraldic pattern. “I gather you’re German,” says young Cusack, summoning his Sherlockian deductive genius. “What makes you say that?” “The coat of arms on your tie: it’s Danzig.” “Actually I am Polish, and it’s Gdańsk!”

Well, so much for my deductive powers, (and Rafal is a secret wannabe-German anyhow) but the arms and flag of the Baltic city — once German, now Polish — combine the usual strong characteristics of any design: simplicity and beauty.

Vienna Views

My written views of the city you will have to wait for (presuming they ever see the light of day), but here are a few photographic impressions from my jaunt to the Kaiserliche Hauptstadt. (more…)

Hark, the Heralds!

by Jack Carlson

133 pages, hardcover, $15.99

In anticipation of a party in Oriel recently, I enjoyed a pint with some friends by the fire in the King’s Arms and was given a copy of this book, mysteriously shrouded in a plastic bag. Jack Carlson’s Humorous Guide to Heraldry is a welcome addition to the Cusackian library. The author, who wrote the book when he was fourteen, is now an Oxford archaeologist (and rower) but his interests span a broad spectrum. (He is currently researching for a work on rowing blazers, a subject unjustly neglected by academics).

Aficionados of the light-hearted-guide-to-heraldry genre will notice one or two gentle riffs off of Sir Iain Moncrieffe of that Ilk’s Simple Heraldry Cheerfully Illustrated, and, since that book is long out of print, evangelists of heraldry will find A Humorous Guide to Heraldry a useful tool for introducing the uninitiated to the appreciable realms of this field. Godfathers will not want their spiritual charges to grow into adults without being able to distinguish the mêlée from the affronté and every life-long student of the world should be able to recognise a cinquefoil or a pheon.

In short: a worthy purchase for the heraldically inclined.

Jack Carlson’s A Humorous Guide to Heraldry is available here.

Pope Francis’s Arms

The Vatican released information about Pope Francis’s coat of arms on Monday but the image they provided of it was very poorly drafted. Many of us were waiting for the Italian heraldic artist Marco Foppoli to craft his own rendering of our new pope’s arms, and he has duly released it today (see above).

The central motif is the emblem of the Society of Jesus — the Christogram with nails on a sunburst. The star represents the Blessed Virgin while the sprig of nard-flower represents Saint Joseph, the patron of the universal church. Thus the three emblems on Pope Francis’s arms together represent the Holy Family.

Further info available from Il Foglio, Fr Z, and Whispers in the Loggia. (more…)

The Kaiserforum

The Unrealised Vision of an Imperial Forum for Vienna

SIDLING UP THE KOHLMARKT and entering the Hofburg through the Michaelerplatz is a glorious architectural experience, but viewing Vienna’s imperial palace from the Ringstraße end, one is left with a certain awkwardness. This is because what is now the Heldenplatz, open to the neighbouring Volksgarten, was conceived as part of a great imperial forum, the Kaiserforum, but the scheme has been left incomplete.

The original impetus for this forum was the plan to build the identical Kunsthistoriches Museum and Natural History Museum across from the Hofburg next to the former imperial stables. Emperor Franz Joseph held a closed competition for four invited architects — Carl Hasenauer, Theophil von Hansen, Heinrich Ferstel, and Moritz Löhr — to conceive of an overall scheme to expand the Hofburg in order to provide an architectural connection to the two new museums. (more…)

Squabbles Over Szekler Flag

In Transylvania, a “flag war” has broken out between Romanian politicians and the representatives of the Hungarian-speaking Szekler people. As România Libera reports, no one is offended by flying the old Hapsburg flag over the fortress of Alba Iulia (De: Karlsburg, Hu: Gyulafehérvár), the Romanian government takes umbrage at the appearance of the blue-and-gold flag of the Szekler (or Székely) people who live primarily in three of Transylvania’s counties. (more…)

Protestant King in His Catholic Realm

George VI in Quebec

In the midst of some unrelated research the other day, I came across these photos of George VI on his first visit to Quebec as King in 1939. I think the Parlement du Québec is probably the only Commonwealth legislature to have a crucifix in its plenary chamber (c.f. ‘Christ at the heart of Quebec’, 25 May 2008). No, no, of course the Maltese do as well, in their surprisingly ugly parliament chamber. But Malta is now an island republic, while Quebec retains its monarchy.

In the above picture, the King and Queen of Canada hear a loyal address in the Salle du Conseil législatif of the Hôtel du Parlement in the city of Quebec. Below, the King speaks at a state dinner in the Chateau Frontenac. Seated is Cardinal Villeneuve, the Primat du Canada and Archbishop of Quebec.

The Other Modern in Madrid

Miguel Fisac’s Church of Espíritu Santo, Madrid

It might be difficult for some to imagine that the architect of the pagoda-like Laboratorios Jorba outside Madrid was an accomplished classicist, but, like many modern architects, Miguel Fisac began his career with more traditional works. His very first commission as an individual was to design a church for Spain’s Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (Higher Council of Scientific Research). The CISC had only been founded in 1939 and was originally housed in existing structures around Madrid. The Church of the Holy Spirit (constructed 1942–1947) was the first newly built structure for the research council, and the fact that it was an ecclesiastic building “eloquently expresses the spirit of commitment between religion and science that animated the new project” (according to the Fundacion Fisac). Around the corner from the Church of the Holy Spirit, the main headquarters of the CISC was designed by Fisac. (more…)

Tradtastic Hertfordshire

The bishops of England & Wales cunningly arranged for the Feast of the Epiphany to fall on the actual Epiphany this year. We had a great big festive lunch at our favourite little Italian place in South Ken, but the night before I went out to Hertfordshire, where I witnessed the tradition of a door being CMB’d with holy chalk for the new year (above).

Those unaware of this tradition can read a bit more here. The C+M+B stands both for Christus mansionem benedicat (“Christ bless this house”) and the names of the Three Magi: Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar.

The Impetuosity of Youth

From the Flickr feed of South Africa’s Etienne du Plessis:

These pictures were taken 2 October 1964: I was the pilot [writes Quentin Mouton]. The pictures are original and not ‘touched up’. The ‘Pongos’ (Army types) were on a route march from Langebaan by the sea to Saldanha. The previous night in the pub one of them had said: “Julle dink julle kan laag vlieg maar julle sal my nooit laat lê nie!” (You think you can fly low, but you will never make me hit the deck). Hullo!!!

I went to look for them on the beach in the morning and was alone for the one picture. I was pulling up to avoid them. In the afternoon I had a formation with me and you can see the other a/c behind me. (piloted by van Zyl, Kempen, and Perold).

A friend by the name of Leon Schnetler (one of the pongos) took the pics. The guy that said “Jy sal my nie laat lê nie!” said afterwards that he was saying to himself as I approached: “Ek sal nie lê nie, ek sal nie lê nie” (I wont go down, I wont go down) and when I had passed he found himself flat on the ground.

Memories from the past.

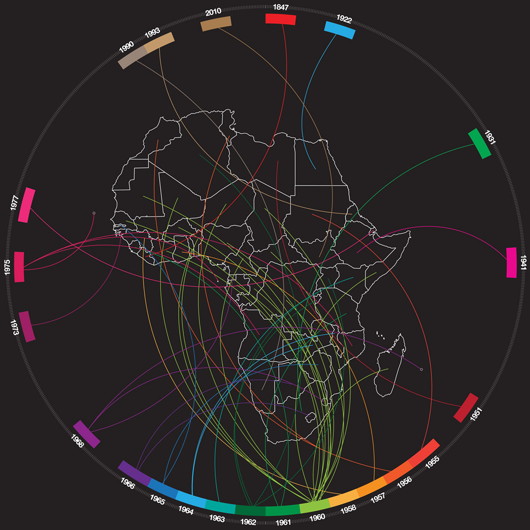

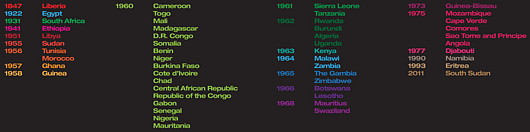

African Independence

The nifty ‘Tumblr’ site Afrographique, which Africa-related facts and statistics in a visually appealing and accessible way, created a handy chart of all the countries of Africa and the years they became independent. The chart correctly gives Zimbabwe’s date of independence as 1965, even though it had a brief return to colonial status for a few months in 1979-1980. Yet it lists Ethiopia’s “independence” year as 1941, despite the fact that Ethiopia has arguably been independent forever.

The Empire of Ethiopia was founded in 1137 with the ascent of the Zagwe dynasty (responsible for the country’s world-famous rock-hewn churches), and while it was occupied by the Kingdom of Italy (whose monarch usurped the title ‘Emperor of Abyssinia’) from 1936 to 1941 with a continued insurgency and a lack of abdication by the legitimate emperor, Haile Selassie, there’s a strong case that Ethiopia retained her independence throughout but merely suffered a temporary foreign occupation.

Despite this arguable discrepancy it’s not nearly so bad as Africa Report, which published a chart claiming that South Africa gained its independence in 1994. Pray tell, what colonial power ran South Africa before 1994? South Africa was unified and gained dominion status in 1910, and Afrographique goes for the much safer independence date of 1931 when the Statute of Westminster was adopted asserting the sovereignty of the dominions of the British Empire. Some Afrikaners claim South Africa did not become independent until the Republic was declared in 1961, but this is neither legally nor constitutionally the case as the country as an internationally recognised sovereign independent nation merely changed its form of government from a monarchy to a republic.

Afrographique has a number of other interesting posts, including African Nobel Prize winners (nine of them South African, across medicine, peace, and literature) and the ten richest Africans (fellow Matie Johann Rupert is #4).

The Historical Sale at Adam’s

800 Years: Irish Political, Literary, and Military History – 18 April 2012

THE ANCIENT PRACTICE of lèche-vitrine is one hallowed by time and tradition. I remember one December day I had a lunch appointment with a friend who worked at the late, lamented Anglo-Irish Bank on Stephen’s Green in Dublin and, being early, I nipped a few doors down to the auction house Adam’s to engage in a bit of what I like to call thing-avarice (which the Germans probably have a word for). We do enjoy taking the occasional peek round the Dublin auction houses to see what’s what, and to examine the cabinet of curiosities that come out from ancient houses and rotting flats and appear in these bright places where commerce and refinement play their strange little waltz. When it comes down to it, though, it’s really just about having nice things — the sort of stuff you want lying around the house inexplicably.

Anyhow, the historical auction at Adam’s is coming up on 18 April and sure enough their senior rival Whyte’s is having a similar sale just a few days later on 21 April. We’ll only look at Adam’s here — if we considered Whyte’s as well, we’d be here all day. (more…)

George Tupou V, RIP

I note with great regret the early death of George Tupou V, the King of Tonga. Readers will remember the King from our 2008 report, Monocled Monarch is the King of Fashion. The blog post was forwarded to the King a year later by one of his honorary consuls, and it’s rather nice to think that a reigning sovereign has visited our little corner of the web.

Requiem aeternam dona ei, Domine: et lux perpetua luceat ei.

Requiescat in pace. Amen.

Charles Taylor & Tu Weiming

Two of the brightest philosophical minds, China’s Tu Weiming and Canada’s Charles Taylor, combined at the Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen in Vienna last year for a dialogue. The video is above, or you can click the link here.

McGill’s Prof. Charles Taylor is the author of A Secular Age and winner of the Templeton Prize. Prof. Tu Weiming is director of the Institute for Advanced Humanistic Studies at Peking University and a leading proponent of Confucian thinking.

State Flags Considered

The famous Matthew Alderman provoked a disputation on Facebook the other day regarding amongst other things (jousting got a mention) the relative merits of U.S. state flags. I touched upon this subject previously in a post discussing the arms of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, when I noted the lamentable tradition in American state flags is for the state seal or emblem to be presented on a blue field. Overall, I have to admit that Maryland has the best flag of any U.S. state: it is heraldic, relatively simple, and overwhelmingly traditional. The Facebook commenting led to an all-out war of annihilation between a lasse of Virginia and one of Maryland on the relative merits of their respective state flags. Right as it is for Virginians to defend the great inheritance of their fair dominion, there is simply no contest here: Maryland’s flag is the overlord.

Just look at Virginia’s (above) state flag! A total yawn-fest, I’m afraid. State seal on blue — how original. It would be far better if they took their ancient coat of arms and followed Maryland’s example by using a banner of arms. In Virginia’s case that would mean a red Cross of St George with the crowned shields of Scotland and Ireland in two quarters and of the quartered French & English arms in the other two quarters. Very handsome.

I don’t really like many other state flags (my geboorteland of New York is no exception: once again a banner of its arms would be much more handsome). Of the few I do enjoy, California rakes highly. It has a certain panache, and the words ‘California Republic’ are a healthy reminder of wherein lies the sovereignty. And interestingly, if the Soviets ever take California (“You mean they haven’t?”) they wouldn’t have to change the flag at all, as it already has a red star.

New Mexico’s is admirably simple and different, but one does worry if it’s a bit too simple: the Zia sun symbol veers eerily close to being a corporate icon. The uber-trad proposal would be to replace it with the yellow-field Cross of Burgundy.

The flag of South Carolina also gets an honourable mention, with its comely combination of palmetto tree and crescent moon. Rendered in red and white instead of blue and white, it is the flag of the Citadel, South Carolina’s military college.

Cardinal Manning

Over at Reluctant Sinner, Dylan Parry has an excellent post on Cardinal Manning, the second man to serve as Archbishop of Westminster. Manning is all too often forgotten, despite being one of the most widely loved and respected men of his generation. His funeral, famously, was the largest ever known in the Victorian era. Besides his wisdom at the helm of England’s most prominent see, the good cardinal’s greatest legacy might be his influence on Rerum Novarum, the great social encyclical of Leo XIII. Dylan is planning on writing further on the subject of Cardinal Manning, giving us something to look forward to. (more…)

Opening Parliament Down Under

I’m a fan of state openings of parliament, so it might be a surprise that I’ve never been to one. I did see some of the practice run-through for the State Opening in Cape Town (which involves a delightful parade of the Cape Town Highlanders and other units from the Castle to Parliament) but unfortunately a social occasion kept me from the actual opening itself. As my luck would have it, I managed to return to live in Blighty again the one year the blasted Government decided not to have a State Opening. Roll on, 2012! Anyhow, down in the Antipodes, the New Zealanders have just had their State Opening of Parliament in the realm’s capital city of Wellington. (more…)

A Breath of Fresh, Northern Air

The Dorchester Review Proves That Canada is Still Thinking

This summer I received an email from my friend Bruce Patterson, all-around nice guy and Deputy Chief Herald of Canada, informing me of a new historical and literary review just founded called the Dorchester Review. Intrigued, I obtained a copy and was pleasantly enthralled with what I found. The first issue of the Dorchester Review contained a variety of thoughtful articles on fascinating subjects. I spent an entire morning sitting comfortably on a café sofa and imbibing the intelligent and enlightening contents of the magazine.

The editors did issue a brief statement explaining the genesis of their new review. They had me at their Pieperian first sentence: “The Dorchester Review is founded on the belief that leisure is the basis of culture.”

Just as no one can live without pleasure, no civilized life can be sustained without recourse to that tranquillity in which critical articles and book reviews may be profitably enjoyed. The wisdom and perspective that flow from history, biography, and fiction are essential to the good life. It is not merely that “the record of what men have done in the past and how they have done it is the chief positive guide to present action,” as Belloc put it. Action can be dangerous if not preceded by contemplation that begins in recollection.

The endeavour of reviewing books, the editors acknowledge, has too often been reduced either to brief puff-pieces in the Saturday insert of the local paper or more high-minded but uncritical praise of like-minded academics for one another. “There are too few critical reviews published today, particularly in Canada, and almost none translated from francophone journals for English readers.” As someone with a lifelong love of Quebec, I am relieved that finally there is a review in my own language willing to take Quebec seriously.

“At the Review,” the editors continue, “we shall praise the good books and assail the bad.”

They also forthrightly explain their rejection of the narrow nationalist perspective that has been on the ascendant in Canada throughout the past century, especially since the foundation of The Canadian Forum. The Dorchester Review effectively throws Canada’s doors open to a more reasoned understanding of the country’s relationship with Europe (Britain and France particularly), America, the Commonwealth, and the world.

But the Dorchester Review is not a publication just for Canadians. There is a great deal of Canada in it, but also a great deal of the world. The second issue (just printed) features articles with titles such as “Why Marx is Still (Mostly) Wrong”, “1789: The First Counter-Revolutionaries”, “What Sort of Autocrats Were the Popes?”, “Can Vichy France Be Defended?”, and “The Scots Fight Back” (the last in response to an article in the first issue: “How the English Invented the Scots”).

Contributing editor Chris Champion is interviewed by CBC Radio here. A number of the contributors (Conrad Black, Paul Hollander, etc.) readers of The New Criterion will already be familiar with. The latest number also includes a book review by this, your humble and obedient scribe.

Head over to dorchesterreview.ca to find out more or subscribe.

Le drapeau « Jacques Cartier »

To be filed under ‘Flags I Never Knew Existed’: the Québécois heraldist Maurice Brodeur designed a flag commemorating the French explorer Jacques Cartier, founder of Quebec and Canada.

The banner was designed to hang as an ex-voto in the Memorial Basilica of Christ the King in Gaspé, conceived in the 1920’s as an offering of thanks for the four-hundredth anniversary of the claiming of Canada by Cartier.

The Great Depression brought the project to a halt, and the church was finally finished in 1969 as a modernist cathedral in wood — the only wooden cathedral in Catholic North America.

Was the flag ever actually executed? I don’t know, but I doubt it.

Ireland’s Viceregal Throne Replaced

This sort of thing is devised simply to raise Cusackian hackles: having been used in every presidential inauguration in the history of the State until now, Ireland’s viceregal throne (above, left) is being replaced as the presidential chair. Supposedly it had become “a bit natty”, and no-one in the Office of Public Works knew so much as a single decent furniture restorer to get it back into condition. Scandalous! Its successor (above, right) was commissioned from furniture designer John Lee, and is rather new rite, as they say in London Catholic circles. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories