Monarchy

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

James II, By the Grace of God

EVERY NOW AND THEN, there is a minor hubbub; perhaps not even enough to be called a hubbub, but call it a hubbub we shall. The hubbub in question is on the subject of James II (seen above, with his father Charles I), our last Catholic king, and the man who (as Duke of York) gave his name to the great city and land of New York. We have previously expounded upon King James on this little corner of the web, but fresh notice was brought by Fr. Nicholas Schofield on his Roman Miscellany blog. In the blog post A Royal Penitent, Fr. Nicholas writes: (more…)

Republicanism is a traitor’s game

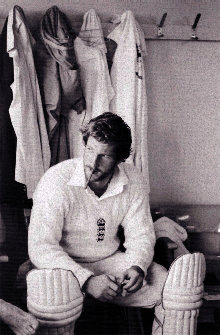

I listen to all these republicans…

If it was down to me I’d hang ’em! I honestly would. It’s a traitor’s game for me.”

SO SPEAKETH Sir Ian Botham, on this occasion to the Guardian, the newspaper of the British ruling class. It’s always reassuring when a public figure speaks out in support of the few remnants of tradition the metropolitan elites allow us to retain, so Sir Ian deserves a firm handshake, a pat on the back, and a pint on the house. Still, there are others (poor souls!) who disagree with the goodly knight. Herein the British Republican movement lists its supporters. They are mostly relative unknowns, except for the former Viscount Stansgate and the rather vulgar Peter Tatchell.

Leanne Wood, a member of the Welsh Assembly, states “I am a republican because I am opposed to the hereditary system”. Opposed to the hereditary system? We presume, therefore, that when she reaches the evening of her years (after a long life sucking off the taxpayer teat) she will not leave her comfortable residence and all her earthly possessions to her offspring, but instead donate them to the Fabian Society. Pity her poor children!

“I believe,” Ms. Wood continues, “in equality not patronage”. To my mind, party politics is more often a source of patronage than the limited constitutional monarchy. As for equality, doesn’t being a member of the Welsh Assembly give her more power and influence than others? Not very egalitarian, but then there are no true egalitarians. Only some who, rather than appreciating the heights of Western civilization, prefer to topple it to the ground in order to establish greater “equality”.

The former Viscount Stansgate, who currently styles himself “Tony” Benn, proclaims that “In a democracy people must be able to elect their own head of state”. The demos beg to differ. The Crown has consulted the people in forty-four different general elections since the enactment of the Reform Act of 1832, and yet the voters have curiously neglected to ever vote a republican party into government.

Mr. Tatchell, meanwhile — whom the Republican movement identifies as a “gay rights and human rights campaigner” (I am glad they concede the dissimilarity in the two concepts) — tells us that “Britain remains a partial, incomplete democracy, steeped in aristocratic privilege.” Hear! Hear! “Why can’t we have a complete, mature democracy,” Mr. Tatchell asks, “where the people elect our Head of State?” Perhaps because democracies which elect their head of state are rarely mature. It seems entirely more mature to keep those institutions which have stood the test of time rather than to arbitrarily destroy them based on what amounts to little more than modish management concepts.

Curiously, at least three people on the Republican movement’s list of supporters are Queen’s Counsel (QCs, or “silks”). They are not so opposed to the monarchy as to refuse the fruits of its munificence, and for that we should praise their pragmatism. Even more curiously, however, nineteen on the list are Members of Parliament. Surely MPs are required to take an Oath of Loyalty to the Crown in order to take their seats? But then perhaps these nineteen are abstentionists along the lines of the Sinn Féiners. While one hesitates to presume to advise the Crown, it might be useful every so often to inquire among the members of Parliament as to which would lend their votes to the abolition of the monarchy, and then deal with them in the manner Sir Ian Botham profers.

“If it was down to me I’d hang ’em!”

Category: Monarchy | Hat tip: The Monarchist.

The Crown in British Columbia

TO VICTORIA, the capital of British Columbia, where the sun never sets on the British Empire. As the Monarchist blog has reported, the Queen of Canada has appointed a new Lieutenant Governor to represent the Crown in her province on the Pacific. In the sumptuous Parliament Buildings of British Columbia, the Chief Justice of the province read the Royal Proclamation, weighted with the Great Seal of Canada, in both native English and appallingly-pronounced French before administering the Oath of Loyalty and the Oath of Office to the Honourable Steven Point, British Columbia’s twenty-eighth Lieutenant Governor. (more…)

Remember!

Two hundred and thirty-one years ago today, the tragedy of our people commenced.

I’ll take the old George over the new one any day of the week.

Elsewhere: Charles Coulombe writes Still Rebels, Still Tories while Daniel Larison reflects on Law and Loyalism.

The Queen in Williamsburg

THE QUEEN HAS once again visited Williamsburg, Virginia’s ancient capital, after an absence of half a century. His Excellency Mr. Timothy Kaine, the Governor of the Commonwealth Virginia, was good enough to call a public holiday in the state, giving public workers the day off in celebration of the Queen’s visit. During the trip, Her Majesty spoke to the General Assembly of Virginia, the oldest legislature in the New World, in Richmond (the current capitol), as well as meeting privately with the friends and relatives of the victims of the recent tragedy at Virginia Tech. In Williamsburg, she received an honorary degree from the College of William and Mary and was the guest at a luncheon at the Governor’s Palace, once the official residence of her predecessors’ viceroys in Virginia. (more…)

A Welcome to the Queen

This little corner of the web naturally extends a very warm welcome to Her Britannic Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II, as she visits the Commonwealth of Virginia this week in commemoration of the four-hundredth anniversary of the plantation of Jamestown and the birth of our country. She will no doubt recall the words of her predecessor, Charles I, who counted his kingdoms of England, Scotland, Ireland, and France (as was still claimed at the time) and added “En Dat Virginia Quintam!” — “And so Virginia makes five!” (to give an approximate translation). We trust the Old Dominion will do all Her Majesty’s former possessions on these shores proudly with a warm and dignified welcome.

May Our Lady of Walsingham, (whose national shrine is in Williamsburg, Virginia) protect, bless, and convert England, Virginia, America, and all the English-speaking world!

Previously: Old Dominion Will Receive Her Majesty

The BBC: Can’t they get anything right?

His Imperial Majesty, Haile Selassie I was the Emperor of Ethiopia up to his death at the hands of Communist revolutionaries, so it seems a bit silly to call him the “former Ethiopian Emperor”. More importantly, however, is that he was a devout Christian and was so opposed to Rastafarianism, which considered Haile Selassie to be the Messiah, that he sent Orthodox missionaries to Jamaica in order to convert Rastafarians to Christianity.

New York Needs a Monarchy

In the business section of today’s New York Sun, of all places, Liz Peek gives us another reason why we need a monarchy. In ‘Why America Needs Its Own Queen’s Award‘, Ms. Peek profiles the Queen’s Award for Enterprise, initiated by Royal Warrant in 1966 as the Queen’s Award for Industry and awarded to British companies for excellence in international trade, innovation, and sustainable development.

In the business section of today’s New York Sun, of all places, Liz Peek gives us another reason why we need a monarchy. In ‘Why America Needs Its Own Queen’s Award‘, Ms. Peek profiles the Queen’s Award for Enterprise, initiated by Royal Warrant in 1966 as the Queen’s Award for Industry and awarded to British companies for excellence in international trade, innovation, and sustainable development.

Of course, Ms. Peek attempts to offer some possible solutions to our detrimental lack of monarchy with regard to this particular aspect, but none of them have quite the appeal of restoring the monarchy. All that would really be necessary would be to pass an amendment removing fourteen words from Article IV, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution. This is the part that requires the member states of the United States to have republican forms of government. This removal would at least give states the option of becoming monarchies, which is only fair, after all.

Category: Monarchy

A Happy Birthday to Her Majesty

In honour of the anniversary of the birth of Her Majesty Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, I raised a glass of Warre’s (Purveyors to the Household of the Queen of Denmark) this evening. May God bless and keep Her Majesty!

Some of you may recall that Her Majesty is of a somewhat artistic temperment. She sent her sketches inspired by The Lord of the Rings to J.R.R. Tolkein while he was alive, and the author liked them so much he had them published in the Danish edition of the trilogy. Above is an episcopal cope designed by Her Majesty in 1988 for the Cathedral of Viborg.

His Royal Highness Prince Christian, the Queen’s grandson and the future King of Denmark.

Naturally, we also wish a very happy birthday and many, many bountiful blessings to another of Christendom’s reigning monarchs: Christ’s vicar and our Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI, who, it seems, is a reader of Chronicles. God bless our Pope, the great, the good!

The Men Who Saved Quebec

The British Crown’s toleration of Catholicism in Quebec was cited by the rebel colonists of the 1770’s as, ironically, an ‘intolerable act’. That the Church of Rome, that bastion of backwards conservatism and slavish hierarchy, could be tolerated in the lands under the power of the British parliament riled the Whigs—the enlightened liberal progressives of the day. Indeed, Benjamin Franklin was even so foolish as to go to Quebec as an emissary of the ‘Continental Congress’ to persuade the natives to rebel against the Crown; Congress’s proposals to ban Catholicism and prohibit the use of the French language ensured he was not successful.

The modern orthodox opinion of historians on the Quebec Act of 1774—the act that granted toleration to the Church—is that it was merely a persuasive exercise to keep les Canadiens from rebelling. A 1989 book challenged this perspective, arguing instead that a handful of British aristocrats were determined to ensure that Quebec did not become another Ireland: where Protestant ascendancy was thrust upon an unwilling nation of Catholic nobles, merchants, and peasants.

The following review by Gary Caldwell was published in a Canadian journal in 2001.

|

Philip Lawson.

The Imperial Challenge: Quebec and Britain in the Age of the American Revolution. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. 192 pages. US$27.95. |

WHY REVIEW A BOOK published twelve years ago? I will explain. But first, let me tell you what it’s about.

When Britain took possession of Canada at the Treaty of Versailles in 1763, it faced an “imperial challenge:” how to integrate into the empire a society fundamentally different from England – in language, religion, and legal and political institutions. At the time, England was vigorously intolerant of Roman Catholicism or “popery,” the religion of its major enemies, France and Spain. British Protestantism was closely tied to the dominant Whig political ideology born of the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89. This doctrinal legacy prescribed that all British subjects were possessed of very definite and equal liberties, liberties endowed upon and limited to those who conformed to the Whig-Protestant definition of being British.

Hence the problem of 1763. English law and constitutional practice allowed only for protestant public officials and elected representatives. This meant excluding the entire French-speaking population, some 70,000 to 80,000 (the “new subjects”) as compared to some 300 Protestants established in the colony (the “old subjects”).

There were two schools of thought as to what should be done. The Whig position, favoured by much of the English political leadership and commercial class on both sides of the Atlantic, was not to accommodate the new subjects. It amounted to an attempted destruction of the local culture and to exclusion of the French-speaking population from all juridical, political and social positions, the hoped-for consequence being assimilation in one, perhaps two, generations. In short, what had been imposed in Ireland with the “protestant ascendancy.”

The opposing school of thought, still marginal in 1763, believed such a policy both impracticable and undesirable. James Murray, Lord Shelburne, Lord Dorchester (Gary Carleton), H. T. Cramahe, Alexander Wedderburn, Lord Mansfield and William Knox not only held that a Protestant ascendancy in Quebec would ruin the colony, they also believed that Quebec society was deserving of being preserved. Murray and Dorchester, who knew Quebec and its people, were adamant: the Canadians were a good “race”—in Murray’s words, “perhaps the best and bravest race on the globe” (p. 48)—and if protected they and their society would flourish and be loyal to the Crown. As it happened, all of these administrators and Crown legal officers, with the exception of Cramahe, were Anglo-Irish or Scottish; not one of them was of English origin.

But how were the Canadians and their culture to be accommodated? There were, as Lawson demonstrates, three distinct dimensions to this accommodation. The first was to respect the prevailing legal code and custom in civil and property matters; the second, to refrain from putting into place an English representative assembly because it would be the instrument of the 300 or so English and American voters in the colony. By far the most important was the third dimension, tolerance in Quebec of Roman Catholicism, which meant the nomination of a Bishop, the tithe and the right of Catholics to hold public office. Dorchester and the others successfully won these concessions in London by 1770, and they were contained in the Quebec Act in 1774, to the horror of much of English public sentiment, and especially the Americans who were more resolutely against “popery” and more Whig than the English themselves.

When Benjamin Franklin arrived in Montreal in 1775 with the invading army of the Continental Congress, he carried secret orders to ban the popish religion and the French language. Fortunately, the Americans were stopped in Quebec by no other than Dorchester, back from getting the Quebec Act through Parliament. At the head of an army of old and new subjects he broke the 1775-76 siege of Quebec.

Lawson’s interpretation is insightful in putting the events into the context of the Irish question. The major players in promoting the accommodation that became the Quebec Act had in mind “the Irish Imbroglio,” and were determined not to repeat the error of the “protestant ascendancy” in Ireland. The Quebec Act emerges clearly as the culmination of thoughtful and courageous policy formulation, a model of generous statesmanship. Hence, as Lawson goes on to argue, the “toleration” of Roman Catholicism in the Quebec Act paved the way for the British Acts of Toleration of 1778.

Lawson also helps understand why Murray, Dorchester and the others came to the conclusions they did about the Canathan problem. These men were essentially empirical conservatives who found the answer “in the past”—Quebec society as they had known it in the 1760s—and the “elastic nature of the British Constitution.” And here Lawson runs smack into the prevailing wisdom in Canadian historiography.

Lawson is insistent on the coincidental nature of any link between the Quebec Act and the American Revolution, affirming that there is no evidence that the inspiration for the Quebec Act was to placate the Canadians so as to keep them apart from the Americans. As this alleged link is one of the most tenacious myths in the Canadian historical consciousness, it is worth citing Lawson:

What can be done to dispose of this myth once and for all? Fifty years ago both Coupland and Burt said that they could find no evidence to justify such an assertion with Lanctot repeating the message in the 1960s, and nothing has yet come to light to contradict them (pp. 123-124).

When I first read this book in the early 1990s and realized how revolutionary his thesis was, I contacted Lawson to talk about his work. In passing, I mentioned that I supposed that The Imperial Challenge must have created quite a controversy in Canadian academic circles. His reply was “No, it has attracted very little attention in Canada.” (I never saw him again. I had arranged to see him a few years later, but just before I arrived in Edmonton he was admitted to hospital for terminal cancer and died shortly afterwards.) In subsequent years, I have been to McGill-Queens Press in Montreal to buy copies of his book to give to friends. Inquiring as to sales, I was told that only a few hundred copies had been sold. And, so far, I have encountered only one reference to Lawson’s book (in Yves Lamonde’s Histoire sociale des politiques au Quebec).

I was curious enough to go back recently to the reviews written when the book came out. There were 16 in Canada in French and English, in the United States and in the United Kingdom; all reviewers were quite positive except one (who wrote two of the reviews). They all commented positively on the extent and depth of the documentation, as well as the fresh reading from parliamentary debates, the personal archives of the principal players, and the press of the day. As for his interpretation of how the Quebec Act came to be, there is no suggestion that he was wrong in any respect. The negative reviewer suggests only that it is pretentious of Lawson to think he has added much to existing work on the Quebec Act. Of the 15 reviewers, a full half explicitly accredit Lawson with drawing out the intention of avoiding the error of Ireland.

Why, then, did a book, critically acclaimed by the author’s peers, which sheds considerable light on a pivotal period in the history of Quebec and Canada, drop out of sight in Quebec, and I suspect in the rest of Canada? Lawson calls into question the conventional wisdom on a very important subject in Canadian history, and no one takes notice. For instance, two prominent Canadians, Gerard Bouchard and John Raulston Saul, social thinkers who are presently reinterpreting Canadian history, make no mention, to my knowledge, of this book. A book that should have caused waves has generated scarcely a ripple.

Perhaps my assessment, as a non-professional historian, is faulty and I would welcome a demonstration of where I have erred. What are the factors that explain the untimely eclipse of Lawson’s work? Could it be simply that Canadian intellectual discourse is shallow, that a seminal work can be dropped into the water and hit bottom generating nothing more than a superficial ripple of perfunctory reviews and listings in compendiums? This is one possible explanation; a more certain explanation lies in ideology.

The ideological axe, starkly put, goes as follows. Quebec’s nationalist, republican-leaning contemporary intellectuals are loath to entertain the idea that a coterie of British Conservatives (half of them aristocrats) literally saved Quebec society by helping to keep it strong enough to withstand the renewed neo-liberal assault led by Lord Durham three quarters of a century later and, then, begin to rehabilitate the Quebec polity (under British institutions) in 1867. Such an idea being beyond the pale (again, the ghost of Ireland), they maintain the myth that the Quebec Act was political opportunism inspired by the American threat. What will it take for Quebec nationalist thinkers to recognize and appropriate the historical reality that Dorchester twice—in the Quebec Act and the siege of Quebec—saved Quebec? It is no exaggeration to assert that, had it not been for this one Anglo-Irish aristocrat, Quebec would likely have become anglicized and, subsequently, integrated into the American empire.

As for English-speaking Canada, the current crop of orthodox historians has long consigned our British imperialist past to the Marxist dust-heap of history: nothing good could possibly have come of it, all imperialisms being, by definition, bad. They are not about to disturb their orthodoxy that in contrast to Imperial Britain, which was incapable of any genuine sympathy for Quebec—only Canadian nationalist intellectuals are enlightened and respectful of Quebec society. So, they too maintain the “political opportunism” interpretation of the Quebec Act, despite its having been refuted by Lawson and his predecessors. Essentially, what we are seeing is a refusal to acknowledge a debt owed to dead white male Protestants (from Ireland and Scotland). But gratitude is not, as the contemporary French philosopher Alain Finkielkraut has pointed out, a hallmark of modern progressive thinkers.

I write this review knowing full well that it is too late for Lawson’s work to be rehabilitated. The Imperial Challenge is among the titles in this year’s McGill-Queen’s clear-the-warehouse sale.

Previously: Hitchcock in Quebec

The Prince of Wales in Philadelphia

THE CITY OF PHILADELPHIA welcomed the Prince of Wales on his recent visit with a guard of honor composed of members of its most ancient military unit, the First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry. Organized in 1774 as the Light Horse of the City of Philadelphia, it describes itself as the “oldest continuously active military unit in service to the nation”. As an active armored cavalry troop, it forms part of the 28th Division, while as an historic and ceremonial unit it is a component of the Centennial Legion (of which my grandfather served as commander). Since the most unfortunate demise of New York’s Seventh Regiment, it probably takes the prize for swankiest unit in the States.

Previously: Old Dominion Will Receive Her Majesty | The Duke of York in New York | Your Royal Highness, Caed Mile Failte

King Jagiello of Poland

My favorite statue in Central Park is that of King Władysław II Jagiełło of Poland, by the Turtle Pond. (more…)

The Cardinal Duke of York

The great Marco Foppoli has designed (and very kindly passed along to me) the badge for the committee which has been assembled to commemorate the two-hundredth anniversary of the passing of the Cardinal Duke of York, or King Henry IX and I as was his style according to the Jacobite succession. I’m not entirely sure what events are being planned, but I believe there will be a conference in Rome around the anniversary in August.

Old Dominion Will Receive Her Majesty

With these words spoken yesterday in the House of Lords, the Queen revealed the plans for her visit to the Commonwealth of Virginia for the upcoming celebrations surrounding the quatercentenary of the first permanent English settlement in the New World. Her Majesty is no stranger to Virginia, nor even to Jamestown, as her very first visit to the New World took place in 1957 when she attended the 350th anniversary celebrations at Jamestown. Following that 1957 official visit to the United States, the Queen opened her parliament at Ottawa for the first time since her accession to the Canadian throne. (more…)

Cousins

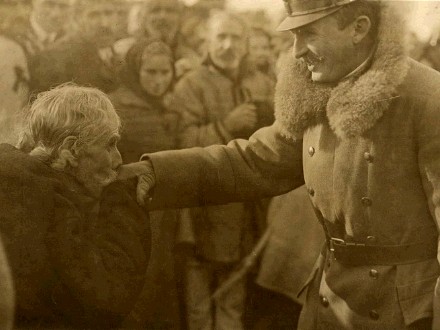

Nicholas II, Tsar of All the Russias and George V, the King Emperor.

Previously: Father & Son | Tennis, Anyone?

Our Holy Emperor

OCTOBER 21 IS the feast of Blessed Charles of Austria, the saintly emperor of that sacred realm whose life stands as an example of the price of sanctity. Charles worked tirelessly for peace both between the peoples of his own numerous realms and between all the nations, seeking to bring to an end the ceaseless and suicidal slaughter of the Great War, in the midst of which he had ascended to the throne of his fathers. A defender of social order, Charles reminds us of our many responsibilities to each other, even though the spirit of our current age would have us clamor only for our supposed rights. In the face of repeated betrayal and intense pressure, he refused to abdicate and so abandon his peoples to their fates, which were terrible indeed. That terrible cross he bore, the crown, was in fact a penitential grace, the sufferings he bore for the benefit of his – and indeed all – people. His reward was not in this world.

The Duke of York in New York

We neglected to mention Prince Andrew’s recent visit to New York in commemoration of the anniversary of the attacks on the World Trade Center. Sixty-seven British subjects died in the September 11, 2001 attacks, and eleven more were non-citizens with British ties. A ceremony was held in Hanover Square, where the British Memorial Garden is being built, followed by a reception at India House, which is located at No. 1 Hanover Square (the brown edifice in the photos above and below). (more…)

James II, Our Catholic King

THIS PAST SATURDAY was the anniversary of the birth of King James II and VII of England and Scotland. The third son of Charles I, he was baptised into the Anglican church six weeks after his birth and was created Duke of York at eleven years of age. James married Anne Hyde, the daughter of the Earl of Clarendon, by whom he fathered eight children, though only two survived past childhood.

In 1664 the Duke of York equipped an expedition to relieve the Dutch of responsibility for their colonies in North America, and henceforth New Amsterdam and New Netherland were known as New York after their new Lord Proprietor.

Sometime during the year 1670 both the Duke and Duchess of York were received into the Catholic Church and stopped attending Anglican services, though the conversion did not become public knowledge until the Test Act (requiring officeholders to receive communion in a Church of England service and take an oath against Transubstantiation) was passed three years later. James was forced to renounce his offices, such as Lord High Admiral of England, though not his titles. At any rate, Anne, the Duchess of York had died in 1671 only a year after her conversion. He married Princess Maria of Modena in 1673.

The Protestant oligarchs felt threatened by the prospect of a Catholic king and thrice tried to pass laws barring James from succeeding to the throne. However his elder brother Charles II, the reigning king, dissolved parliament each time before the bill was to be passed. King Charles II died in February 1685, (having reconciled himself to the Catholic faith before his end) and thus the Duke of York was proclaimed James II of England and VII of Scotland. A private Catholic coronation was held at Whitehall Palace on April 22 before the public coronation the following day on the feast of Saint George, which was performed according to the rites of the Church of England.

James had appointed the Catholic Thomas Dongan

as Governor of New York in 1682.

The Protestant oligarchs’ fears that James would end their hegemonic grip on Scotland and England proved well-founded as in 1687 he issued a Declaration of Toleration as King of Scotland, allowing Catholics, Episcopalians, and other non-Presbyterians to hold public office and the right of public worship, and a Declaration of Indulgence as King of England removing the laws penalizing non-attendance or non-communion at Church of England services, permitting non-Anglican worship in private homes or chapels, and abolishing religious oaths for public offices. Furthermore, James had allowed Catholics to hold positions at the University of Oxford for the first time since the Protestant Revolution. More provocatively, he tried to transform Magdalen College Oxford into a Catholic seminary. He had already reckoned with the rebellion of the Duke of Monmouth who proclaimed himself king two years earlier but had been captured, tried, and executed for treason. With the birth of a Catholic son and heir, Prince James Francis Edward, in 1688 a cabal of seven Protestant nobles issued an invitation to William of Orange, the Protestant Stadtholder of the Netherlands. A few months later, William of Orange duly arrived and usurped the throne, having already married James’ daughter Mary from his first marriage. The two ruled jointly as William and Mary.

Unwilling to create a popular martyr as had happened with the executed Charles I, William allowed James to escape and fled to France where Louis XIV gave the exiled monarch the use of a palace and an ample pension. James was intent on returning to his birthright, however, and took advantage of the Irish parliament’s refusal to recognise William’s usurpation of the throne. The King landed in Ireland in March of 1689 at the head of a Franco-Irish army but was defeated by William in the famous Battle of the Boyne in July 1690, and returned to his place of exile in France.

There, Louis allowed him to live in the château of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and offered to get James elected King of Poland but James felt this would prevent any chance of a Stuart again holding the throne of England. From that time onwards, James led a simple life of penance in reparation for his sins (he had had a number of mistresses in his younger days) and finally died in 1701. He was entombed in the Chapel of St. Edmund within the English Benedictine church on the Rue St. Jacques in Paris, while his brain was sent to the Scots College in Rome, his heart to the Visitandine Convent at Chaillot, and his bowels divided between the College of St. Omer (the exiled English Catholic school, now Stonyhurst in Lancashire), and the nearby parish church of St. Germain where they remained until they were desecrated by a Revolutionary mob and lost forever. His monument at Saint-Germain, however, was rediscovered in 1824 and is proudly displayed there to this day. There is also a monument to James and the Stuarts in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (c.f. Roma – Caput Mundi).

Aside from the pious tradition that Edward VII was received into the Church on his deathbed, James II was the last Catholic king (and as good King Edward never reigned over New York, James is even more certifiably so for us). There is a lovely coronation ode to James which I just might bring to your attention someday. But for now, reflect and remember our monarchs of old and pray that God in His mercy might grant us good Catholic rulers in stead of the shabby lot we elect today.

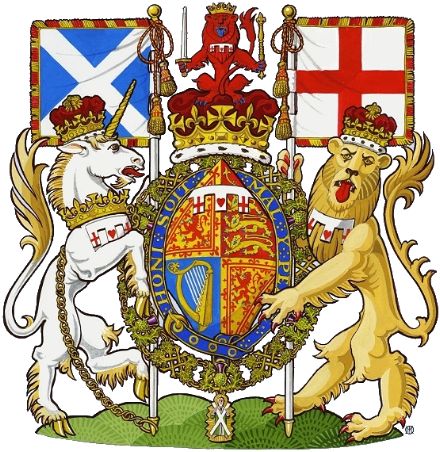

The Heraldic Congress

THE ROYAL BURGH of St Andrews was recently host to the largest gathering of heralds since the Middle Ages for the XXVII International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences. Taking place in the last week of August, the Congress was opened with a grand ceremony in the University’s Younger Hall which was attended and addressed by the XXVII Congress’s patron, the Princess Royal (Scottish arms below). The event lured state heralds, genealogists, heraldists, and other enthusiasts from around the world, as well as local heralds from the Court of Lord Lyon (Scotland’s heraldic authority) and the personal heralds of Scots noble houses. Aside from the ceremonial, a broad variety of lectures were given on various topics in the realm of heraldry and genealogy. We present to you here a number of photographs from the event, which have been taken from the Congress website as well as from the personal collections of Mr. John Gaylor, a member of the Heraldry Society of Scotland, and Mr. David Appleton of the American Heraldry Society.

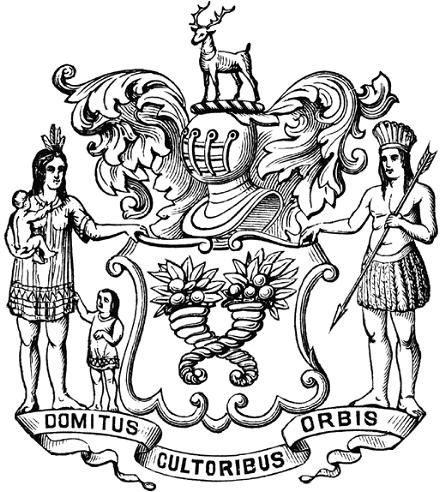

The Great Seal of Carolina

THE ROYAL CHARTER which erected the Province of Carolina created the colony as a county palatine, similar to Durham, Chester, and Lancashire back in England. However, instead of being ruled by a Count Palatine (or Prince-Bishop in Durham’s case), Carolina, named after England’s martyr-king Charles I, was to be ruled by eight Lords Proprietor, the eldest of which would hold the title of Lord Palatine of Carolina. The charter even allowed for the granting of titles…

…to Men well deserving the same Degrees to bear, and with such Titles to be Honoured and adorned, AND WHEREAS by our form of Government It was by our said Predecessor Established and Constituted, and is by us and our Heires and Successors for ever to be observed, That there be a certain Number of Landgraves and Cassiques who may be and are the perpetual and Hereditary Nobles and Peers of our said Province of Carolina, and to the End that above Rule and Order of Honor may be Established and Settled in our Said Province.

The granting of the titles of ‘landgrave’ and ‘cassique’ never really took off, but the Lords Proprietor did have a rather splendid Great Seal for their own private fiefdom in the New World, an impression of which is happily preserved by the good people of the South Carolina Department of Archives and History down in the Palmetto State.

The obverse (above) shows the arms of the Province of Carolina with two cornucopias in saltire. Joseph McMillan, Director of Education for the American Heraldry Society, has posited that this is the probable origin of the cornucopia depicted in the Great Seal of the State of North Carolina, the larger of the two Carolinas. The motto reads “Domitus Cuitoribus Orbis” which perhaps some learned reader could translate properly. The reverse (below) depicts the eight heraldic shields of the Lords Proprieter, surrounding a simple Cross of Saint George. Some readers may recall this configuration being used, in a much simplified form, in the heraldic achievement recently devised by the College of Arms for the Senate of North Carolina, mentioned and depicted previously on this site. The arms of the North Carolinian Senate also show the cornucopias in saltire in the crest above the shield.

UPDATE:

The commenter below is correct; the motto is ‘Domitus Cultoribus Orbis’ or ‘Tamed by the Husbandmen (cultivators) of the World’, as shown clearly in this alternate depiction which I have discovered.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- How to Make a Pope April 24, 2025

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories