Military

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

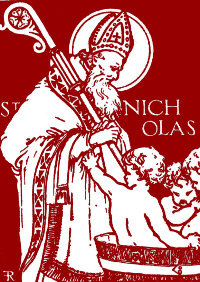

St. Nicholas of the Seven Seas

ONE OF OUR correspondents sends word that Russia is to name the fourth of her Borei-class ballistic missile submarines Николай Чудотворец, which is to say “Saint Nicholas”. The Borei-class vessels are the first series of Russian strategic submarines to be launched in the post-Soviet era. The previous subs in the class have been named the Yuri Dolgoruki (after Prince Yuri I, founder of Moscow), the Alexander Nevsky (after the Grand Prince of Vladimir & Novgorod venerated as a saint in the Eastern churches), and the Vladimir Monomakh (after the Grand Prince of Kievan Rus). The Saint Nicholas is of course not the first boat or ship to bear the name of New York’s patron saint. There was HMS St. Nicholas as well as a Spanish naval ship San Nicolas in the 1790s, eventually captured by the Royal Navy and commissioned as HMS San Nicolas. A Sealink (later Stena) ferry named St. Nicholas traversed the Harwich/Hook-of-Holland route from 1983 until it was renamed Stena Normandy in 1991 and transferred to the Southampton/Cherbourg route. Numerous merchant vessels took the saint’s name and patronage throughout the nineteenth century.

ONE OF OUR correspondents sends word that Russia is to name the fourth of her Borei-class ballistic missile submarines Николай Чудотворец, which is to say “Saint Nicholas”. The Borei-class vessels are the first series of Russian strategic submarines to be launched in the post-Soviet era. The previous subs in the class have been named the Yuri Dolgoruki (after Prince Yuri I, founder of Moscow), the Alexander Nevsky (after the Grand Prince of Vladimir & Novgorod venerated as a saint in the Eastern churches), and the Vladimir Monomakh (after the Grand Prince of Kievan Rus). The Saint Nicholas is of course not the first boat or ship to bear the name of New York’s patron saint. There was HMS St. Nicholas as well as a Spanish naval ship San Nicolas in the 1790s, eventually captured by the Royal Navy and commissioned as HMS San Nicolas. A Sealink (later Stena) ferry named St. Nicholas traversed the Harwich/Hook-of-Holland route from 1983 until it was renamed Stena Normandy in 1991 and transferred to the Southampton/Cherbourg route. Numerous merchant vessels took the saint’s name and patronage throughout the nineteenth century.

The Union Defence Force

From 1912 to 1957, South Africa’s military was called the Union Defence Force (the Union in question being the Union of South Africa, the other USA). The Nationalist government renamed it the South African Defence Force (Suid-Afrikaanse Weermag) in 1957, prior to the declaration of the Republic of South Africa in 1961. After the introduction of universal suffrage in 1994, the SADF was merged with the MK (Umkhonto we Sizwe, the ANC’s terror branch) and APLA (Azanian People’s Liberation Army, the terrorist wing of the Pan-Africanist Congress), as well as the Self-Protection Units of Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi’s Inkatha Freedom Party, into the South African National Defense Force (SANDF, or SANDEF), which remains the name of the country’s armed forces today.

Reclaiming his Birthright

Blessed Emperor Charles’s two homecomings to Hungary after the overthrow of the Hapsburgs are worthy of the greatest spy novels, except they are fact: the hushed secrecy and underground preparations, the airplane contracted under a false name, the disguises used to sneak over borders. In his first attempt, Charles — the Apostolic King of Hungary — made it all the way to Budapest, only to be persuaded to return to exile by the self-appointed regent, Admiral Horthy (a naval commander in what, by then, was a land-locked country).

The King’s second attempt to reclaim his power was much more considered and deliberate, and he spent some time securing a loyal power base of local nobility before pressing on to Budapest by armoured railway train. The King’s force made it to just outside of the Hungarian capital before they were overwhelmed by troops loyal to Horthy — who, in order to maintain their loyalty, neglected to inform the soldiers and officers that the “rebels” they were fighting were actually those of their King and Queen.

Along his path to the capital, the King was greeted by fervent crowds, and stopped at least twice to review small detachments of troops and to show himself in person to his loyal Hungarian subjects. The King had returned, but sadly not for long. After the failure of this second attempt, the Allied powers refused to allow the Imperial & Royal family to remain in mainland Europe, and exiled them to the Portuguese island of Madeira, where the Emperor-King grew ill and eventually died. He is entombed on the island today — a source of great pride, I am told, to the Madeirans.

Elsewhere: Miracle Attributed to Blessed Charles (Norumbega)

The Band-leader & the Sergeant-Major

I came across these two characters in the Castle in Cape Town, the oldest building in South Africa and still home to the Cape Town Highlanders and Cape Garrison Artillery.

Victory Day in Moscow

I recently discovered that we receive the television channel Russia Today in our humble little flat here in Stellenbosch, and have spent the past few days enjoying it. They are shockingly truthful (almost nasty) in their reporting of international relations, in so far as the truth — for the moment — tends to favour the Russian case in world affairs, and make NATO look like a bunch of ninnies. Saturday — May 9 — was Victory Day in Russia, in which the defeat of Nazi Germany in the Second World War is commemorated and celebrated. RT showed many minutes of splendid highlights from the great parade in Red Square, and I just sat and enjoyed it.

Cuban Army Polo

The Cuban Army polo team visits New York in 1939. How different the Americas might be had Fidel Castro preferred the polo of his patrician background to the baseball he is known to be fond of. If only he had attended the Cavalry School instead of the Universidad de la Habana!

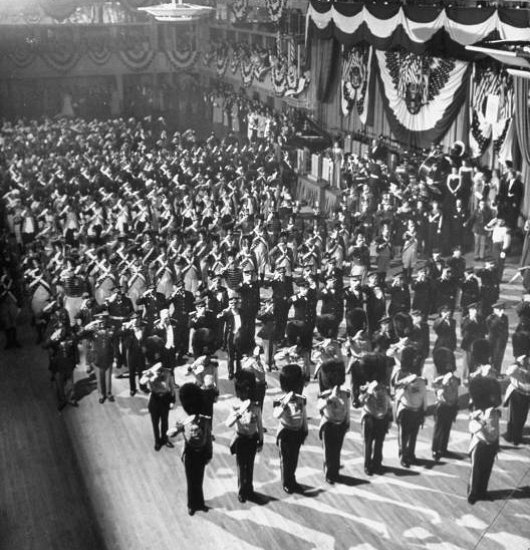

Old Guard Ball, 1949

The Annual Ball of the Old Guard of the City of New York, Commodore Hotel, 1949.

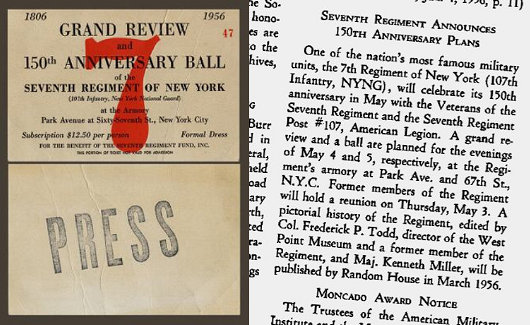

200 Years was an Empty Anniversary for New York’s ‘Gallant Seventh’

Flipping through a military journal from early 1956, I stumbled upon a rather depressing note announcing the Seventh Regiment’s plans for celebrating its 150th anniversary. A reunion of old comrades on Thursday May 3, then a grand review the following day, and topped off by a formal ball on the evening of Saturday May 5 at the regiment’s beautiful armory on Park Avenue at 67th Street.

Why should such a splendid celebration spark dour thoughts? Chiefly because, having survived over a century and a half since the unit was founded amidst pints of ale in the Shakespeare Tavern on the corner of Nassau and Fulton, the Seventh Regiment was abolished before it could celebrate its 200th anniversary in 2006. The Seventh was deactivated as a regiment in 1993, though its “lineage” was transferred to the 107th Corps Support Group, which in 2006 was “consolidated” into the 53rd Army Liaison Team. The regiment’s unique collection of historical artifacts — the legal property of the Veterans of the Seventh Regiment — was seized by the State in an act of highly dubious constitutionality and its armory, built without a cent of public money from the pockets of the regiment’s members in the 1880s, was also taken and transferred to a conservancy to run it as an events & performing arts venue, over protests from both veterans groups and the local community.

Why should such a splendid celebration spark dour thoughts? Chiefly because, having survived over a century and a half since the unit was founded amidst pints of ale in the Shakespeare Tavern on the corner of Nassau and Fulton, the Seventh Regiment was abolished before it could celebrate its 200th anniversary in 2006. The Seventh was deactivated as a regiment in 1993, though its “lineage” was transferred to the 107th Corps Support Group, which in 2006 was “consolidated” into the 53rd Army Liaison Team. The regiment’s unique collection of historical artifacts — the legal property of the Veterans of the Seventh Regiment — was seized by the State in an act of highly dubious constitutionality and its armory, built without a cent of public money from the pockets of the regiment’s members in the 1880s, was also taken and transferred to a conservancy to run it as an events & performing arts venue, over protests from both veterans groups and the local community.

Paris Arts & American Arms

Maj. T. L. Johnson’s Cartographic Mural on Governors Island

One of the best aspects of the inter-war construction of Governors Island is that the refinement of McKim Mead & White’s architecture is matched inside by a series of interior murals painted under the auspices of the WPA. These murals often veered towards the refreshingly jocular, as can be seen in the War of 1812 mural in Pershing Hall (a corner of which is captured here by photographer Andrew Moore). The mural by Major Tom Loftin Johnson (educated at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris) depicted here, however, is a map of the area under the purview of the Second Corps, U.S. Army headquartered at Governors Island; namely the states of New York, New Jersey, and Delaware, and the then-territory of Puerto Rico.

Debating Stauffenberg

The recent release of the Hollywood film “Valkyrie” has brought the July ’44 plot back into the limelight. Much debate has focussed on the central figure of Count von Stauffenberg, especially the motivation and inspiration for his attempt to overthrow the Nazi regime. Writing in Süddeutsche Zeitung, Richard Evans (Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge) asks “Why did Stauffenberg plant the bomb?” Prof. Evans argues that the Count’s contempt for liberalism combined with his (Stefan George-influenced) romantic nostalgia « make him ill-fitted to serve as a model for the conduct and ideas of future generations » .

A week later, the Süddeutsche Zeitung published “Unmasking the July 20 plot“, a response to Evans by Karl Heinz Bohrer, the publisher of Merkur and a visiting professor at Stanford. Bohrer counters Evans on two fronts. « Firstly Evans’s lesson consisted of historical half truths, contradictory theses and slanderous allusions to Stauffenberg’s character; and secondly, such distortions differ very little from the view held by West German intelligentsia regarding the events of July 20th 1944 and the conspirators who were, for the most part, of aristocratic Prussian stock. … For a proper understanding of the how the plot against Hitler of 1944 is seen and judged today, one should bear in mind that today’s horizon has shifted. »

« There is no question that like Ernst Jünger and Gottfried Benn, Stauffenberg’s first spiritual influence, Stefan George, entertained pre-fascist fantasies. And there is also no question that the young Stauffenberg’s reverence for the medieval ‘reich’ was reactionary – in a similar vein to Novalis’s ideas in ‘Die Christenheit oder Europa’. But what does that mean? Neither of them had political ideas that could in any way have served as a model for democratic European societies in the second half of the twentieth century. But to fundamentalise this tautological insight to effectively deny the conspirators any moral or cultural relevance is blinkered and constitutes intellectual bigotry. George, Jünger and Benn’s pre-fascist fantasies contained important modernist symbols which mean they cannot be judged by political moralist criteria, alone. The same goes for Stauffenberg and his friends who – in a different way to the “idealistic” Scholl siblings and their circle – represented a calibre of ethics, character and culture class of which today’s politicians and other bureaucratic elites can only dream. »

In that same week, Bernard-Henri Lévy — the omnipresent French man of letters — waddled into the debate with “Beyond the war hero” in the pages of Le Point. BHL proclaims the release of “Valkyrie” is unquestionably good, for it is inherently good for the world to honour its heroes. « Riveting as it is however, this film poses certain questions that are too complex and too delicate to be resolved solely within the logic of the Hollywood film industry. »

In a moment of pure irony, Lévy attacks the lack of accuracy in the film while making a gross historical error himself. The philosopher asks whether « raising someone to hero status does not always happen, alas, to the detriment of precision, nuance and history itself. The film shows Stauffenberg’s integrity very well. It shows his courage, the nobility of his views, his firmness of spirit. But what does it tell us of his thoughts? What does it teach us about why he enthusiastically joined the Nazi Party in 1933? » In actual fact, while Stauffenberg’s family members were concerned that he was “turning brown” the Count never joined the Nazi Party; not in 1933, not ever.

In a sense, Lévy has answered his own question in that Stauffenberg’s elevation has apparently taken place to the detriment of precision and history in that Lévy is apparently unaware of quite central historical facts of the case.

Previously: Stauffenberg

First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on white laid paper, 9 in. x 7 1/4 in.

c. 1811-1813, Rogers Fund

Previously: The Prince of Wales in Philadelphia

The Victory Parade, Dublin 1919

UPDATED Peter Henry’s article from Trinity News corrects my errors.

Persuant to our previous photograph of the Union Jack proudly snapping from Dublin’s General Post Office, one of our dear friends & loyal readers, a former editor of Trinity College’s newspaper, sends this photo of the 1919 Victory Parade through the streets of Dublin after the end of the Great War. The red, white, and blue here flies from the top of Trinity College, and the view looks down D’Olier Street (if I recall correctly) towards O’Connell Street in the distance. The classical portico on the left marks the entrance to the Irish House of Lords.

It is worth remembering that a great deal more Irish served in the forces of the Crown than in any republican armed forces or groups. The memory of Ireland’s great sacrifice during the First World War was shamefully neglected from the 1930s until about ten or fifteen years ago. It was a pity that the famous old Irish regiments were disbanded when independence came in 1921, rather than being continued under a native Irish command. Gone the Connaught Rangers and Dublin Fusiliers, and all the great battle honours won by Irishmen from Waterloo to far off India. (Two Irish regiments still exist in the British Army, the Royal Irish and the Irish Guards). Still, in remembrance of the dead of the First World War, one can visit the War Memorial Gardens by the banks of the Liffey, beautifully designed by Lutyens and completed after independence. The cost was split between the Irish and British governments, and, in the post-war downturn, half the workers were Irish veterans of the British Army and half were veterans of the formerly rebel forces.

Ireland remained neutral during the Second World War but declared a state of emergency, which is why the time of the war is often known in Ireland as “the Emergency”. Allied and Axis soldiers who washed up or crash-landed in Ireland found themselves interned in camps, but the Irish soldiers guarding them were only armed with blank ammunition. (Allied internees were often allowed to escape). The law of the day forbade any Irish citizen from joining a foreign military, but many soldiers of the Irish Army, policemen of an Garda Siochana, and many Irish civilians left for Britain to join the Allies in the fight, and were not punished on their return. When the port of Belfast suffered a German bombardment, fire brigades from Dundalk to Dublin were sent north irrespective of the border in order to help quell the flames.

Returning to Trinity, flying the Union Jack in 1919 would not have proved controversial in the slightest (after all, it was still the official flag of the land), but the crowds gathered again on College Green in 1945 to spontaneously celebrate the news of Germany’s surrender. The flag of Ireland with those of all the Allied nations were flown from the flagpole of Trinity, but some tactless student had placed the Union Jack at the top and the Irish Tricolour at the very bottom, below even the Soviet hammer-and-sickle. The crowd noticed this and began to howl, but some more thoughtful Trinity man swiftly took the colours down and raised them again with the Tricolour to the fore. The joyful spirit resumed.

Remembering the Seventh

It is entirely appropriate that November 11 — Armistice Day — both falls during the month of the Holy Souls and on the feast of St. Martin of Tours. It’s not unlikely that the souls in Purgatory added their voices to plead for peace that November of 1918, and St. Martin, who had himself been a Roman soldier, was no doubt leading the cause from Heaven. (Indeed, his father having been in the Imperial Horse Guards, St. Martin was born into a military family).

God and the Emperor

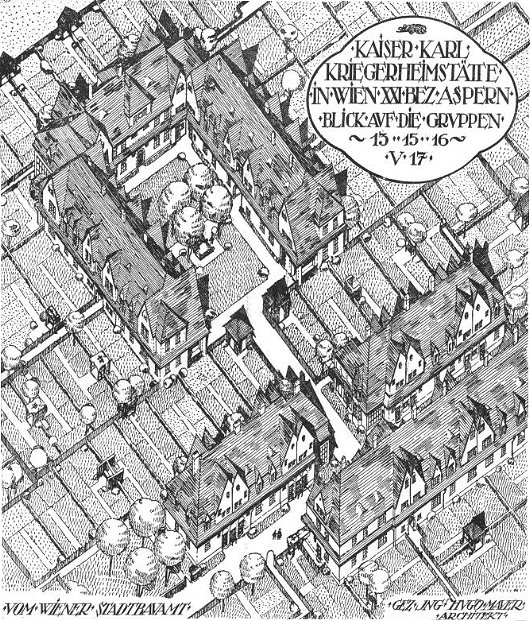

The Kaiser Karl Soldiers’ Homes

An unexecuted design. The architect later designed a number of housing projects during the First Austrian Republic.

Russia Turns a Cinematic Page in History

Big-budget film celebrating anti-Communist hero & White Russian leader Admiral Kolchak is partly funded by Russian government

Here’s a film that has it all: naval battles, mutiny, revolution, civil war, brave men, beautiful women, sin, sacrifice, and betrayal on multiple levels. But “Admiral” («Адмиралъ»), which opened in Russia this month, is notable for another reason: this is the first major film depicting the tsarist White Russians as the good guys to receive at least part of its funding from the Russian government. The eponymous hero of the film is Alexander Kolchak, the naval commander and polar explorer who later led part of the White Army fighting the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War.

The Badge of the Cincinnati

George Washington’s Society of the Cincinnati medal was auctioned off at Sotheby’s last year for a whopping $5,305,000. Founded by General Washington and other officers of the Continental and French armies who served in the American Revolution, the Society of the Cincinnati is the oldest and most prestigious of America’s many hereditary societies.

Society of the Cincinnati medal was auctioned off at Sotheby’s last year for a whopping $5,305,000. Founded by General Washington and other officers of the Continental and French armies who served in the American Revolution, the Society of the Cincinnati is the oldest and most prestigious of America’s many hereditary societies.

Louis XVI was himself a member, and the Society was known as the ordre de Cincinnatus in France, where it was added to the hierarchy of orders (even though it was not, strictly speaking, an order) as ranking just below the Order of Saint Louis.

General Washington’s Cincinnati badge was, after his death, given to the Marquis de Lafayette whose descendants kept it in the family until the auction last December.

The South African Fleet Review

Africa’s oldest navy parades its newest frigates

Fleet reviews are not very common occurrences. According to legend, the first fleet review took place when King Henry VIII on a whim gave the order to assemble his navy’s ships as he wanted “to see the fleet together”. On that occasion, the omnivorous monarch was rowed from vessel to vessel and enjoyed a repast on each. The tradition of the monarch reviewing the fleet continued, and usually took place to commemorate the coronation, to welcome a visiting monarch, or to commemorate some other event or occasion of great import.

Since the time of George III, British fleet reviews have typically taken place at Spithead between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight. The 1814 review celebrating the Treaty of Paris was the last to be composed of only sailing ships, and included fifteen ships of the line and thirty-one frigates: “the tremendous naval armaments which has swept from the ocean the fleets of France and Spain and secured to Britain the domain of the sea”. The 1937 Coronation Fleet Review was made famous by the BBC radio commentary given by Lieutenant-Commander Thomas Woodrooffe. The retired naval officer had met up with a number of chums from his more sea-worthy days in a pub before the broadcast. Woodrooffe’s commentary was so incoherent that he was taken off the air within a couple of minutes; as the fleet was specially illuminated in the evening, Lt.-Cdr. Woodrooffe continually repeated “the Fleet’s lit up”; “lit up” also being a euphemism at the time for being drunk.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories