History

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

South African VCs in the Russian Civil War

The South African contribution to the Russian Civil War is not very well known, nor particularly well researched by historians of the period. Several South African officers who found themselves in Europe by the time of the armistice ending the Great War volunteered to serve in Russia fighting the Bolsheviks — either with the Allied force there or with the White forces themselves.

Among the South African volunteers were two winners of the Victoria Cross — Major Oswald Reid (above, left) of Johannesburg, and Lt Col John Sherwood-Kelly (above, right) from the Eastern Cape.

The South African aviation pioneer K R van der Spuy — who ended up a major general — managed to serve from the early days of 1914 all through the First World War. His engine failed in Russia, however, and he was taken prisoner after a forced landing in Bolshevik-held territory. The Soviets released him from imprisonment in 1920.

As Cdr W M Bisset wrote elsewhere: “Despite the harshness of the Russian winter and the growing prowess of the Red Army, South African officers were able to make a valuable contribution to the operations of the Allied and White Armies which is well illustrated by the important posts which they held and the awards they received.”

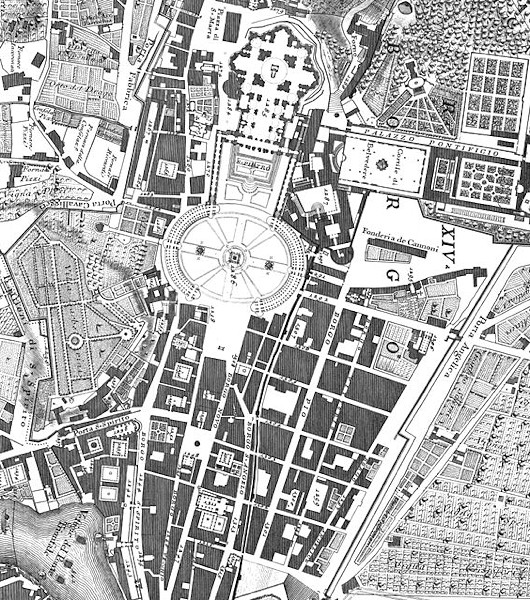

The slums of the Louvre

We are so used to the now-familiar image of the palais du Louvre — with its central wing and flanking arms wide open to the Jardin des Tuileries — that it’s easy to forget just how recent a creation this ensemble is. The palace began as a square chateau expanding upon the site of the medieval citadel. The Tuileries it eventually stretched towards was then an entirely separate palace. In-between the Louvre and the Tuileries was a whole neighbourhood of buildings, streets, alleyways, and squares.

Henri IV built the grande galerie on the banks of the Seine connecting the Old Louvre to the Tuileries by 1610, but the Louvre we know today really only came together under Napoleon III in the 1850s.

Until that point, a slum was built right up to the walls of the Palace, and even within the old courtyard. Balzac, predicting that one day all this would be cleared, noted the slum with amusement as “one of those protests against common sense that Frenchmen love to make”. (more…)

The Delarue Proposal for Parliament

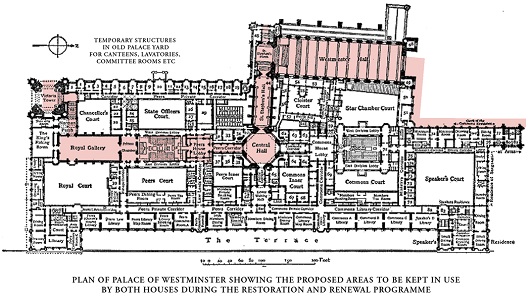

Peers & MPs could still convene in the Palace during renovations

The Royal Gallery set up for temporary use as the House of Lords chamber

Credit: Anthony Delarue Associates

MPs are kicking up a fuss about the controversial proposals to shut down the entire Palace of Westminster for perhaps as long as eight or nine years. (Previously mentioned here.) The building is completely structurally sound, and on solid foundations, but the accumulation of mechanical, electrical, and technological systems over the course of the past 150 years has created a confused mess within the walls of the palace. Electrical lines compete with fibre-optic cables, telephone wires, not to mention various heating and cooling pipes, and even some lingering telegraph wires. No one’s quite sure what is what and all of it is getting older. Even just accessing it to figure out what to do requires taking the building apart — removing wood panelling, drilling through walls, etc.

Parliamentary authorities commissioned management consultants from Deloitte to come up with a number of options on how to tackle this problem, but in their Independent Options Appraisal they treated this merely as an ordinary engineering job, rather than recognising the Palace as one of the most important places in British history both medieval and modern and, importantly, one still in constant daily use.

The Joint Committee formed of members of both the Lords and Commons perhaps unsurprisingly endorsed the option Deloitte claimed was the quickest and cheapest: that the Lords, Commons, and everyone else be chucked out of the Palace entirely and that temporary accommodation be found nearby.

Further investigation by respected former minister Shailesh Vara MP suggested that Deloitte had failed to take into account that any VAT costs on this major project go back into the Treasury anyhow, and that there was a failure to account for the loss of revenue if the Lords are moved into the government-owned Queen Elizabeth II Conference Centre nearby. The QE2 is a profit-making venue popular with private clients, after all, and deploying it towards full-time legislative use will mean another significant loss for the Treasury. Meanwhile, in the courtyard of Richmond House on Whitehall, £59 million would be spent on building a new chamber for the House of Commons. This would be a permanent ‘legacy’ structure even though once the renovations to the Palace are complete there would be no use for it whatsoever.

The architect Anthony Delarue, having been taken on a tour of the Palace’s working underbelly by the engineers from the Restoration and Renewal programme, came up with an alternative proposal. Looking at the structure of the House of Lords chamber and the adjacent Royal Gallery, he realised that these two rooms could be maintained and occupied, with temporary services (electricity, heating, etc.) run from external sources. This would allow the renovation team to shut down the Palace’s systems entirely and re-do them completely, while the spaces in mind would still be able to be put to use. The Commons could then meet in the Lords chamber (as the wartime precedent suggested) and the Lords could meet in the Royal Gallery. Or indeed vice versa depending on the wishes of both Houses.

The advantages of this are no need for taking up the QE2 conference centre (with consequent loss of revenue for the Treasury) and no need to waste tens of millions on a temporary-but-permanent Commons chamber in the courtyard of Richmond House. In addition, both houses would be allowed to maintain their presence in the Palace of Westminster, in accommodation suitable to the traditions of the “Mother of Parliaments”.

Of course, the Restoration and Renewal programme ran a “high level review” of Delarue’s proposals and pooh-poohed the whole idea, amazingly claiming that it would probably cost £900 million more than the Deloitte option the Joint Committee preferred. Anthony Delarue has now written some comments responding to this review, pointing out that it relies on outrageously pessimistic estimates of timing, assumptions that are beyond the worst-case scenarios of project management.

MPs were expected to debate the matter last month, but the campaign organised by Sir Edward Leigh MP and Shailesh Vara MP has found considerable support among other Members of Parliament and it is believed the powers that be are looking for a delay. The Government have promised a free vote on the issue when it comes up for debate, which may very well be before the end of February.

● Anthony Delarue Proposal

● Deloitte Independent Options Appraisal

● Joint Committee Report

● High Level Review of Delarue Proposal

● Anthony Delarue Response to High Level Review

Credit: Anthony Delarue Associates

Colonel Moore

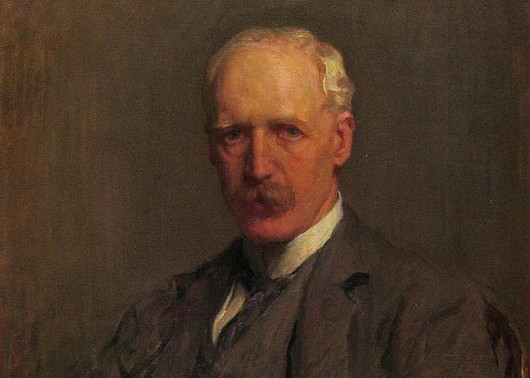

Senator Colonel Maurice George Moore, Companion of the Order of the Bath, is an understudied figure from that remarkable period of rapid transformation in Ireland’s political history. While certainly far from typical, Colonel Moore’s experience reflects the changing age rather well.

He was born in 1854 at Moore Hall in Co. Mayo where his family — English settlers who had converted to Catholicism — made their home. His father, George Henry Moore, was known as a kind landowner, and when his horse Coranna won the Chester Gold Cup during the height of the Great Famine, the £17,000 winnings were spent on giving each tenant a cow and importing thousands of tons of grain to relieve their hunger. During this dark period, not a single family was evicted from the Moore lands for non-payment of rent, and not a single Moore tenant died of hunger.

Younger son Maurice was educated locally before heading off to Sandhurst and was commissioned a lieutenant in the Connaught Rangers in 1874. The Ninth Xhosa War brought him to South Africa for the first time, also seeing action during the Anglo-Zulu War not much later. Promoted to captain in 1882 and major in 1893 it was the great Boer War (1899–1902) which transformed Moore’s entire world.

As a field commander Moore was highly regarded and proved himself capable at the Battles of Ladysmith, Colenso, Spioen Kop, and Vaal Krantz. His conduct in combat notwithstanding, Moore was appalled by the atrocities committed by his own side against the Boer civilian population — women and children herded into concentration camps where many starved to death while, just beyond the barbed-wire fences, British troops were exceptionally well provisioned. One wonders what effect the stories of the Great Hunger that took place just a few years before his own birth may have had on witnessing these horrible and frighteningly avoidable horrors.

With the Boers finally defeated, Moore ended up a colonel and was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath in honour of his achievements. In South Africa he became fluent in the Irish language having started to learn it from soldiers under his command. Back home in Ireland, Col Moore became active in promoting the study of Irish language and history, whether at evening schools on his family’s estates or in joining Conradh na Gaeilge and supporting compulsory Irish at the National University.

When Óglaigh na hÉireann — the Irish Volunteers (now Ireland’s defence force) — was founded in 1913 his military experience was judged useful and he was appointed to its provisional committee. He opposed Redmond’s takeover bid a year later but nonetheless followed him into the National Volunteers when the split did occur, the Redmondites putting themselves at the disposal of the British forces during the Great War. Colonel Moore’s final break with the constitutional nationalist leader came after the Easter Rising, and he joined Sinn Féin the following year. In 1918 his son Ulick was killed in action during the German’s spring offensive.

Given  Col. Moore’s long experience in South Africa, Dail Éireann appointed him the secret Irish envoy to that country. With the creation of Seanad Éireann in 1922, Col. Moore was appointed a senator and began his legislative career which continued the entirety of the Free State Senate’s existence.

Col. Moore’s long experience in South Africa, Dail Éireann appointed him the secret Irish envoy to that country. With the creation of Seanad Éireann in 1922, Col. Moore was appointed a senator and began his legislative career which continued the entirety of the Free State Senate’s existence.

Starting out in Cosgrave’s ruling Cumann na nGaedheal party, Senator Moore quickly began to oppose the government policy. The Boundary Agreement late in 1925 provoked his defection to the new Clann Éireann (or People’s Party) when it was founded early on in 1926. Just two months later, in March 1926, de Valera founded Fianna Fáil which took on what little momentum Clann Éireann had. Once Dev’s efforts proved their worth at the ballot box in 1928, with voters electing eight Fianna Fáil senators, Col Moore sat with the party in Leinster House.

In 1932, the voters put Fianna Fáil in power for the first of many times and de Valera began his reshaping of the Irish state, culminating in the 1937 Constitution of Ireland that has stood the test of time. Significantly, Ireland is the only successor state to have emerged from the First World War to have preserved its constitutional democracy, and much of this is due to Dev’s instinctive conservative republicanism. When the Constitution came into effect in 1937, An Taoiseach appointed Col Moore to the newly constituted Seanad, and he continued to serve as a Senator up until his death in 1939.

Stockholm in the Swinging 60s

The Solemn Opening of the Riksdag was the state opening of Sweden’s parliament, seen here in a recording from 1960 during the reign of Gustaf Adolf. Years ago I wrote about Oskar II’s opening of parliament.

Alas, all this was done away with as part of the constitutional innovations of 1974, and the Swedish legislature is now opened with a much simpler ceremony.

via Karl-Gustel

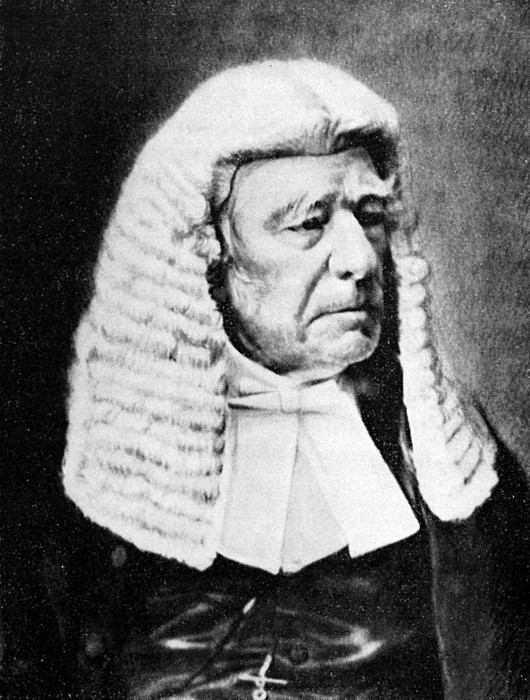

Sir Christoffel Brand

Look at that cragly visage! It belongs to Sir Christoffel Brand, the first Speaker of the House of Assembly in the Cape Parliament.

Brand was born in Cape Town in 1797 and left for the Netherlands in 1815, where he studied at Leiden. In 1820 he was awarded a doctorate in law based on his dissertation Dissertatio politico-juridica de jure coloniarum on the legal relationship between colonies and the metropole, and returned to the Cape. (more…)

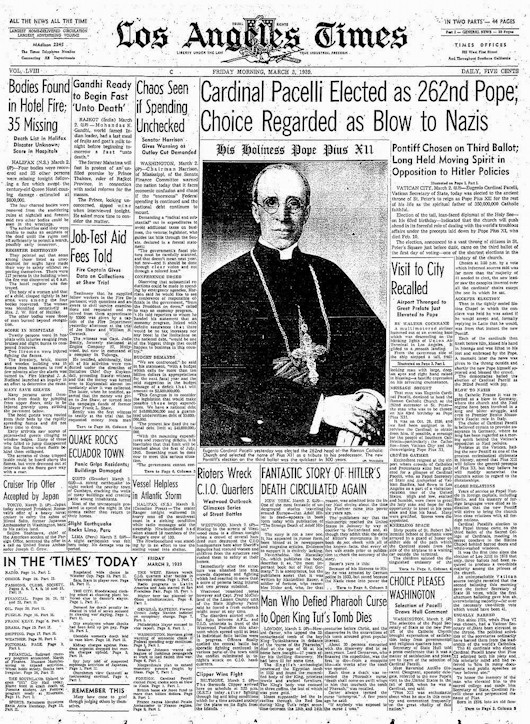

The L.A. Times on Papa Pacelli

How News of the Election of Pius XII was Received in 1939

The case against Pope Pius XII, accusing him of complicity in the crimes of Nazism, has been so thoroughly debunked — by Jews like Gary Krupp and Rabbi Dalin more than any — that it is no longer even worth refuting.

Still, it’s interesting to read the Los Angeles Times’s coverage of his election as Supreme Pontiff in the difficult year of 1939:

BLOW TO NAZIS

… The choice of Cardinal Pacelli is believed certain to provoke annoyance in Germany, where he long has been regarded as a moving spirit behind the Vatican’s opposition to Nazi policies.

As the news report goes on to note, Cardinal Pacelli was elected in only three ballots — the quickest papal election since that of Leo XIII in 1878.

Christmas on College Green

There are some good (if brief) shots of the Irish House of Lords chamber in this Christmas ad for the Bank of Ireland, 0:35-0:45.

The former Irish Houses of Parliament on College Green in Dublin were the first purpose-built parliament building in the world, and were purchased by the Bank of Ireland after the parliament was abolished by the Act of Union in 1800.

Unfortunately a condition of sale was demolishing the elegant octagonal Commons chamber at the centre of the building, to prevent it being used in the effort to have the Act of Union repealed.

Sir Thomas Cusack (1505-1571) has the distinction of having at times served as the presiding officer of both the upper and lower houses of the Irish Parliament. From 1541-1543 he was as Speaker of the House of Commons, in which role some scholars argue he was a prime mover behind the legislation erecting Ireland as a kingdom.

In the following decade he served as Lord Chancellor of Ireland, presiding in the House of Lords, from 1551 until 1555 when revelations about his involvement in the creative finances of Sir Anthony St Leger’s viceregal regime brought about Sir Thomas’s dismissal and (temporary) imprisonment.

He returned to favour when the Earl of Sussex was appointed viceroy, but never again held high office.

Of course, all that was before this neoclassical building was erected, when Parliament met mostly in Dublin Castle.

Marinus Willett

In one of the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum’s American wing, behind the Tuckahoe-marble façade of the old Assay Office (moved here from Wall Street), hangs this portrait of Col. Marinus Willett of the Continental Army’s 5th New York Regiment.

Born in 1740, the second of thirteen children, Willett attended King’s College before being commissioned a lieutenant in a New York provincial regiment during the Seven Years’ War (or French and Indian War as it’s known more locally). (more…)

Mendicant Architecture in Mediaeval Oxford

An interesting video from two American academics on the subject of Mendicant architecture in mediaeval Oxford, with some three-dimensional theoretical reconstructions of the Dominican and Franciscan houses in the city.

Both orders returned to Oxford in the twentieth century. The Capuchins refounded Greyfriars in 1910 and it was recognised as a permanent private hall (PPH) of the University in 1957. Its end as an academic institution was announced sadly on its fiftieth anniversary in 2007, but Greyfriars continues as a Capuchin friary.

Blackfriars under the Dominicans is still going strong, exercising a triple function as a priory of the Order of Preachers, a house of studies for the English province of the Order, and a PPH of the University of Oxford.

Judging Dress

After some absence, The Sybarite has returned and, in A Love Supreme, he weighs in on the very important matter of judicial dress.

I am, it will surprise no-one to know, deeply traditionalist in such matters. I can see the argument for discarding formal court attire in cases involving children, who might be intimidated by wigs and gowns (as a child, I myself would have been as happy as a pig in the proverbial). But I feel strongly that “work clothes”, whether worn by judges, barristers, politicians or clerks in Parliament, are important. They are part of the persona. You are not Alf Bloggs, you are Mr Justice Bloggs and you are performing an important public role. When you put on the clothes, you put on the role. Of course, I am fighting a rearguard action here – I know that the tide of public opinion is against me. If the clerks at the Table in the House of Commons still wear wigs in ten years’ time, I will be (pleasantly) surprised.

As the Supreme Court was set up in the modish New Labour years, it was inevitable they would dispense with much of the ceremonial. The Justices wear lounge suits to hear cases, though I think in some cases the barristers still wear wigs and gowns. The one concession has been the black-and-gold gowns which the Justices don for special occasions. These are fine so far as they go – and, as observed above, Lady Hale of Richmond likes to accessorise hers with a Tudor bonnet – though they bear on the back the badge of the Supreme Court, which I think looks a bit tacky and smacks of footballers’ names and numbers on the back of their shirts. But they also look a bit odd worn over lounge suits or equivalent. At least successive Lord Chancellors since the role was recast by Blair have retained formal court dress for high and holy days. Mind you, the current occupant, Miss Truss, does look a bit like the principal boy in a pantomime when she wears knee breeches. But fair play to her for continuing to wear the traditional robes, even if the full-bottomed wig seems now to have gone the way of the dodo.

It could be worse. The Supreme Court Justices could wear ghastly zip-up gowns like their American counterparts – you just know they’re made of nylon – over their suits, though I have some time for Justice Ginsberg for adding a lace jabot to tidy up her garb a little. But ceremonial is something that Britain does so well. The Supreme Court could have looked so much better with Justices in gowns and traditional judicial clothing. A wig here and there wouldn’t go amiss.

I couldn’t agree more. Especially on the matter of the badge of the Supreme Court on the back on the gowns, which is simply naff. (See image below.)

But why do the justices of the Supreme Court have (what I think of as) chancellorial gowns anyhow? What is the origin of this style of black-and-gold gown? Did it start with the Lord Chancellor and spread to the Speaker or vice versa? Or have some species of judge always worn chancellorial gowns? The chancellors of universities have likewise adopted it, though its precise form varies from institution to institution, as one might expect in matters of academic dress.

Incidentally, I was speaking with Bob Geldof the other day about Senator W. B. Yeats, about whom Mr Geldof has done a documentary. As we were discussing Yeats’ contribution to the Irish Senate, Mr Geldof mentioned that Yeats had been in discussions with Hugh Kennedy, the Chief Justice of the Irish Free State, about introducing new designs for Irish judicial dress. The results, according to just about everyone, left much to be desired and so the British tradition carried on for the most part. As is so often the case, doing nothing is the least bad option.

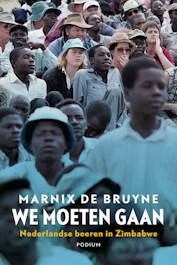

The Dutch in Rhodesia

…and why they stayed there.

Journalist Marnix de Bruyne has shed new light on the post-war wave of Dutch immigration to Rhodesia with his new book, We moeten gaan. Nederlandse boeren in Zimbabwe (‘We Must Go: Dutch Farmers in Zimbabwe’).

Journalist Marnix de Bruyne has shed new light on the post-war wave of Dutch immigration to Rhodesia with his new book, We moeten gaan. Nederlandse boeren in Zimbabwe (‘We Must Go: Dutch Farmers in Zimbabwe’).

Why did so many people emigrate from the Netherlands in the fifties? Why did hundreds of them choose to settle in what was then called Rhodesia, today’s Zimbabwe? And why did so many of them stay after 1965, when the country was led by a white-minority regime, faced an international boycott and was engulfed in a bloody guerrilla war?

De Bruyne attempted to answer these questions through a recent seminar at Leiden University’s African Studies Centre. The university has rather handily made a recording of the seminar available online.

Daar’s ook ’n interview (in Nederlands) met Mnr de Bruyne in Mare, die koerant van die Universiteit Leiden.

(Dave: hierdie post is vir jy!)

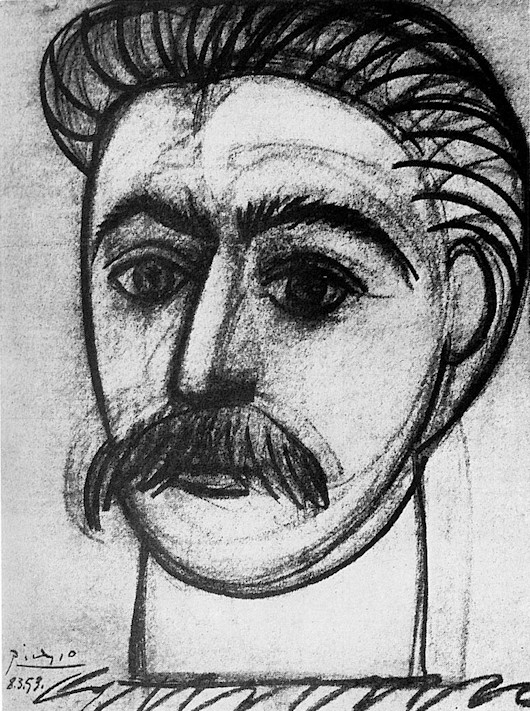

The Death of God the Father

When Stalin’s death was announced on Friday, 7 March 1953, Aragon called in Pierre Daix and rattled off a shopping list of features to honour Stalin in a special issue of Les Lettres françaises. […] Since Picasso had always refused to do a portrait of Stalin from a photograph, Daix sent a telegram to him at Vallauris saying, ‘Do whatever you want,’ and signed it ‘Aragon’.

Picasso’s drawing of Stalin, which depicted him as a curiously open-eyed young man, arrived at the very moment Les Lettres françaises went to press. Daix took the picture to Aragon. He admired it and said that the party would appreciate the gesture. While it was being set into the front page, office boys and typists crowded round the picture. Everyone thought it ‘worthy of Stalin’.

Daix was overjoyed to be the one who had commissioned Picasso’s first portrait of the Soviet leader and rushed it down to the printers. But a few hours later, when the edition had been run off, the mood in the building had completely changed to one of fear. Journalists from L’Humanité, passing by, spotted the drawing and cried out that it was unthinkable that any Communist publication should consider such a representation of ‘le Grand Staline’.

Pierre Daix promptly rang Aragon at his apartment; Elsa Triolet answered. She told him angrily that he was mad to have even thought of asking Picasso for such a drawing.

‘But really, Elsa,’ Daix broke in, ‘Stalin isn’t God the Father!’

‘Yes, he is, Pierre. Nobody’s going to reflect much about what this drawing of Picasso signifies. He hasn’t even deformed Stalin’s face. He’s even respected it. But he has dared to touch it. He has actually dared, Pierre, don’t you understand?’ […]

Antony Beevor & Artemis Cooper (1994, London)

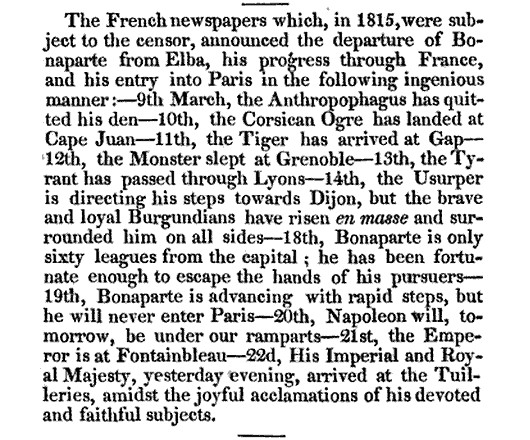

The Anthropophagus Has Quitted His Den

The Museum of Foreign Literature Science and Arts was a Philadelphia periodical edited by the prodiguously talented and unjustly neglected Eliakim Littell.

In January 1831 his review published this little snippet of headlines claimed to have been clipped from French newspapers:

The French newspapers which, in 1815, were subject to the censor, announced the departure of Bonaparte from Elba, his progress through France, and his entry into Paris in the following ingenious manner:

March 9 THE ANTHROPOPHAGUS HAS QUITTED HIS DEN

March 10

THE CORSICAN OGRE HAS LANDED AT CAPE JUAN

March 11

THE TIGER HAS ARRIVED AT GAP

March 12

THE MONSTER SLEPT AT GRENOBLE

March 13

THE TYRANT HAS PASSED THOUGH LYONS

March 14

THE USURPER IS DIRECTING HIS STEPS TOWARDS DIJON

but the brave and loyal Burgundians have risen en masse

and surrounded him on all sidesMarch 18

BONAPARTE IS ONLY SIXTY LEAGUES FROM THE CAPITAL

He has been fortunate enough to escape the hands of his pursuersMarch 19

BONAPARTE IS ADVANCING WITH RAPID STEPS

But he will never enter ParisMarch 20

NAPOLEON WILL, TOMORROW, BE UNDER OUR RAMPARTS

March 21

THE EMPEROR IS AT FONTAINEBLEAU

March 22

HIS IMPERIAL & ROYAL MAJESTY, yesterday evening, arrived at the Tuileries, amidst the joyful acclamation of his devoted and faithful subjects.

In the Old Dutch East Indies

Little Holland’s rule over this vast land – today the world’s largest Muslim country by population – never loomed large in the European imagination (the Netherlands excepted) and thus has been too easily forgotten. Peter van Dongen’s Rampokan series of graphic novels (in Herge’s ligne-claire style) is the most prominent recent attempt to shine some light on the Dutch East Indies and it has obtained a bit of a cult following.

The colonial architecture went through the usual transformations, from awkward hybrids of the motherland and the vernacular to a cool and crisp classical elegance of the later imperial buildings. Henri Maclaine Pont’s work at Bandung is probably the most successful Dutch take on local building traditions, and in some ways Geoffrey Bawa is his spiritual offspring.

The ministries of Indonesia’s government still convene in elegant Dutch colonial buildings, though the names have all changed. The Daendels Palace is now the Finance Ministry, Buitenzorg is now Bogor, and the old Koningsplein is now the Medan Merdeka or Freedom Square. (more…)

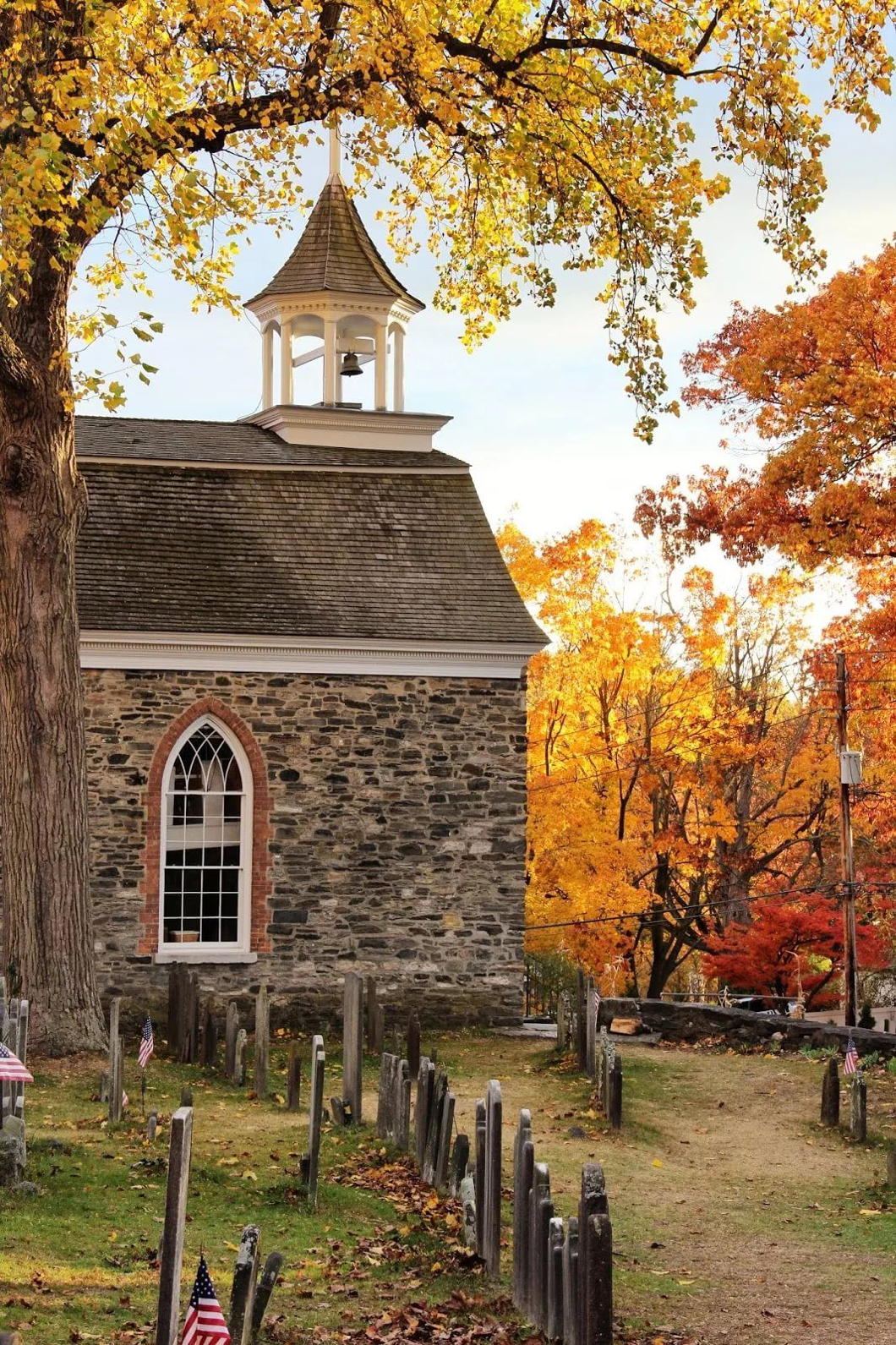

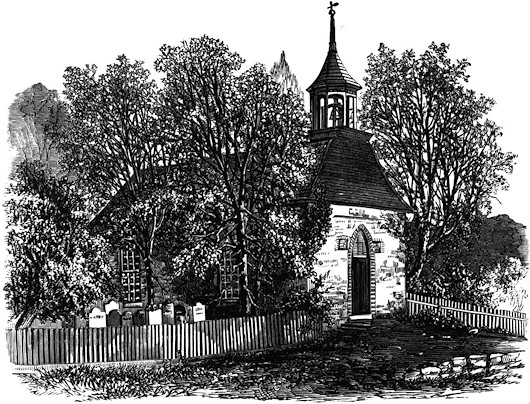

The Old Dutch Church of Sleepy Hollow

If there is any season which is plus New-Yorkaise que les autres then it must be autumn, and around the time of Hallowe’en in particular.

Thanks to the fertile imagination of Washington Irving, buried in the cemetery of the Old Dutch Church in Sleepy Hollow, the Hudson Valley is the spiritual home of this ancient Celtic feast now implanted in the New World.

The other day I dusted off the huge single-volume complete works of Irving – almost the size of an old Statenvertaling – and re-read his most famous tale, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”.

Irving describes the position of the Old Dutch Church:

The sequestered situation of this church seems always to have made it a favorite haunt of troubled spirits. It stands on a knoll surrounded by locust trees and lofty elms, from among which its decent whitewashed walls shine modestly forth, like Christian purity beaming through the shades of retirement. A gentle slope descends from it to a silver sheet of water bordered by high trees, between which peeps may be caught at the blue hills of the Hudson. To look upon its grass-grown yard, where the sunbeams seem to sleep so quietly, one would think that there at least the dead might rest in peace.

On one side of the church extends a wide woody dell, along, which raves a large brook among broken rocks and trunks of fallen trees. Over a deep black part of the stream, not far from the church, was formerly thrown a wooden bridge; the road that led to it and the bridge itself were thickly shaded by overhanging trees, which cast a gloom about it even in the daytime, but occasioned a fearful darkness at night. Such was one of the favorite haunts of the Headless Horseman, and the place where he was most frequently encountered.

The tale of the Headless Horseman is now, partly thanks to various popular reinterpretations of it, well known even outside the Hudson Valley. I remember as a wee lad growing up in that part of the world our Scout uniforms had a badge bearing the image of the “Galloping Hessian”.

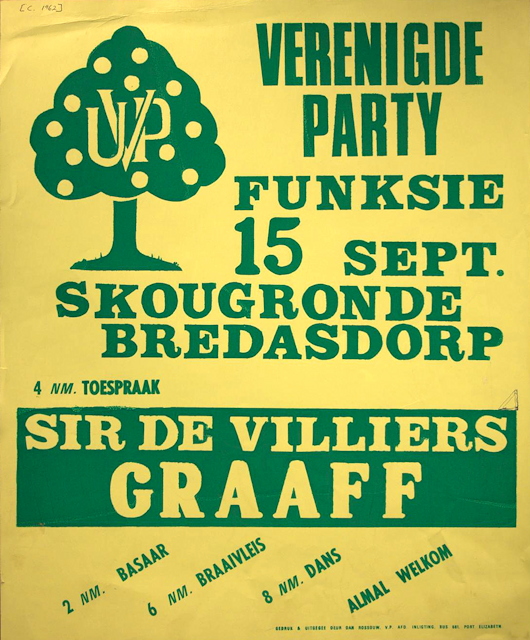

Party in the Overberg

Alongside a bazaar, a braai, and dancing, a speech by Sir De Villiers Graaff is the selling point of this poster advertising a United Party (Verenigde Party) get-together in the beautiful Overberg region of the Cape.

“Sir Div” was the inheritor of one of only twelve South African baronetcies and led his party from 1956 until 1977 when it merged with the Democratic Party of verligte ex-Nationalists to form a new entity.

The broadly centrist party had lost power to the republican Nats (creators of apartheid) in 1948, and suffered splits that led to the creation of the Liberal Party and the United Federal Party in 1953, the National Conservative Party in 1954, and the Progressive Party in 1959.

The party’s emblem was a happy little citrus tree.

Botswana and Hereditary Power

To any observer it must be obvious that hereditary power of some kind is natural and most of the time inescapable. It’s not that you need to be born into power to wield it, but experience shows it doesn’t hurt. Since I was born, there has been just one American presidential election (2012) in which a member of either the Bush or Clinton families was not either the official candidate of their respective party or a significant contender for that role.

In Canada, the current prime minister has sailed into office solely on a combination of good looks and being the son of a previous prime minister. In Ireland there are no fewer than forty-one families who have had three or more members elected to the Oireachtas (or to the Commons before it). The relatives and descendants of Timothy Sullivan managed to elect thirteen members between 1874 and 2016 as MPs, TDs, senators, or MEPs. Sullivan’s son and great-grandson both served as Chief Justice of Ireland to boot.

Sir Seretse Khama

Botswana — the most succesful state in Africa by many gauges — today celebrates the fiftieth anniversary of its assuming the mantle of sovereignty after eighty-one years as a British protectorate. Given that the United States, Canada, and Ireland are generally viewed as succesful countries, the hereditary aspect of power might help explain the comparitive success of Botswana, a multiparty state with free and fair elections, relative to its neighbours. The fourth and current president is Ian Khama, formerly a lieutenant general in the Botswana Defence Force. President Khama is the son of Sir Seretse Khama, the Balliol man who led his country and its people to independence fifty years ago and served as Botswana’s first president. Sir Seretse in turn is the grandson of King Khama III, last kgosi of Bechuanaland before the protectorate and leader of the Bamangwato tribe.

When Sir Seretse Khama became leader of Botswana it was the third poorest country in Africa — now it is the sixth richest on the continent in terms of GDP per capita. In a continent not known for good government Botswana, though not without its problems, is an oasis of stability and order.

At today’s celebrations for the fiftieth year of independence, President Khama wasn’t taking any credit for his country’s success: “Where we may have failed we take the blame. Where we succeeded we thank God.”

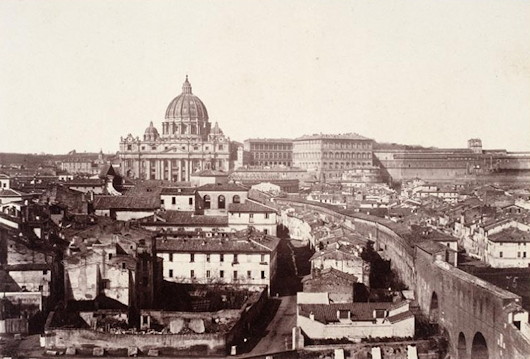

The Spina di Borgo

The Baroque is a style of joy. It is often hailed (or derided) as the most Catholic of styles and in some sense this is true. The festivity and physicality of the Baroque reflect the God that Catholics worship — “the Love that moves the Sun and other stars” as Dante put it — but a Love made incarnate, made man, in a very real and tangible world.

The Baroque is also the style of the surprise: the corner turned to an unexpected vista or the jet of water sprinkling a king’s unsuspecting courtier.

One of the most superb examples of this was the great basilica church of Saint Peter in Rome where prince, pilgrim, and pauper alike moved in a dark warren of palaces, hovels, churches, and alleyways, perhaps catching an occasional glimpse of the great dome looming as they closed in on San Pietro, finally to emerge from the shadow into the great light of the piazza.

That warren of buildings was the Spina di Borgo (“Spine of the Borgo”) but this experience is now sadly lost to us since the 1930s when the Kingdom of Italy’s fascist premier Benito Mussolini decided to raze the neighbourhood. Instead we now have the long boulevard called the Via della Conciliazione, named in commemoration of the Lateran Treaty establishing formal relations between the Holy See and the Italian state.

While Il Duce ostentatiously took credit for this urban crime by symbolically swinging the pickaxe beginning demolition, the concept, though flawed, was in fact an old one. Leon Battista Alberti submitted proposals during the reign of Pope Nicholas V (mid fifteenth century), and numerous other architects — Carlo Fontana, Giovanni Battista Nolli, Cosimo Morelli — drew up similar plans. The Piazza San Pietro only took its now instantly recognisable form in the 1650s when the curved flanking collonades enclosed the space like great welcoming arms superbly framing the basilica’s façade.

Mussolini turned to Marcello Piacentini — an accomplished if sometimes uneven architect — assisted by Attilio Spaccarelli. Piacentini favoured closing off the view from the avenue with a closed collonade, echoing Bernini’s own plans for the piazza, but was overruled.

The razing of the Spina presented a problem in that the undemolished buildings left flanking the Via della Conciliazione were now mostly at odd angles to the new boulevard. Piacentini attempted to solve this by flanking the road with two rows of obelisks that doubled as streetlamps providing a line directing the viewer towards the great basilica beyond, otherwise unimpeded by any visual interruption.

Overall the construction of the Via leaves a rather boring and clinical feeling. The charm and chaos of the Spina has been replaced by a clean and dull boulevard, useful for little more than traffic efficiency and crowd control. The loss of the Spina di Borgo is mourned.

An Old Name Returns to Banking

or: What Daniel O’Connell has to do with the 2008 Banking Crisis

Daniel O’Connell was a remarkable man by any stretch of the imagination, and is most often recalled for his part in bringing about the Relief Act of 1829 which emancipated the Catholics of Great Britain and Ireland from an officially oppressed legal status. Among his many achievements, however, was in London in 1825 founding the National Bank of Ireland.

As the RBS Group’s website notes, O’Connell:

…helped draw up the agreement that established it, spoke at public meetings to drum up support for it, invested in it, attended its first board meetings and, in 1836, was appointed its governor. He became an important figurehead for the new bank and there was even a proposal, not implemented, to put a bust of O’Connell on the bank’s notes.

The National Bank was created with the aim of injecting cash into the rural economy in Ireland, and its charter ensured that half of its returns would accrue to local shareholders in the country. O’Connell, not the best manager of financial affairs, ended up accruing huge personal debts to the bank and had to be quietly bailed out by several others (commencing a tradition of surruptitious banking amongst the nation’s major politicians).

Anyhow, the National Bank expanded across Britain and Ireland. In 1966 its Irish core was sold to the Bank of Ireland, and the English and Welsh branches were acquired by the National Commercial Bank of Scotland (which was a 1959 merger of the National Bank of Scotland and the Commercial Bank of Scotland). This, in turn, merged into the Royal Bank of Scotland in 1969, with the superfluous National Bank branches being turned into Williams & Glyn’s Bank the following year. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories