History

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

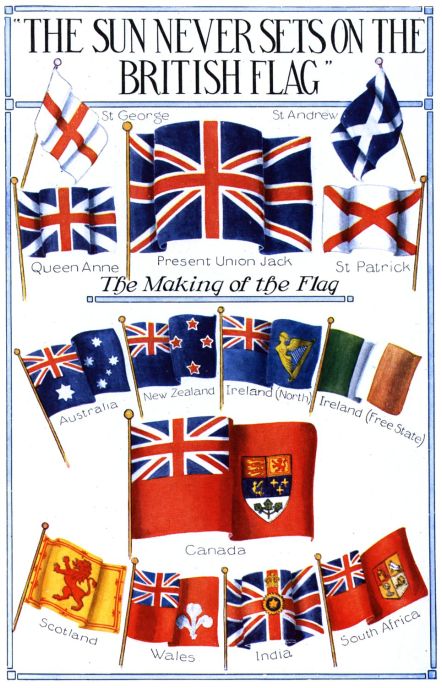

Flags of the British Nations

It is interesting how little-valued accuracy was in the depiction of flags “back in the day”. In this illustration, for example, the flags of Wales and “Ireland (North)” are mere inventions while the Scottish and Indian ones are arguable yet imprecise.

The “Welsh” flag depicted is a red ensign that is defaced with the three feathers of the Prince of Wales.

The “Ireland (North)” flag is handsome, but nonexistent. Northern Ireland had an official flag in use from 1953 until the Parliament of Northern Ireland was prorogued in 1972. (It was never recalled, and has since been superseded by the Northern Ireland Assembly). The flag of “Norn Iron” was a banner of the province’s coat of arms.

The flag of Scotland shown here is not actually the national flag (depicted above as the “St. Andrew” flag) but rather the Scottish royal standard, which is often (and improperly) used as an alternative national flag.

The Indian flag depicted is actually the flag of the Viceroy of India, which (admittedly) was sometimes used as a national flag for India. More often, however, a blue or red ensign was used, defaced with the Star of India.

The Canadian flag depicted here was changed in 1957, when the arms of Canada were themselves changed. The maple leaves in the bottom compartment of the sheild were specified to be “gules” (red). Up to that point, they had previously almost always been rendered “vert” (green). The Canadian flag itself was very controversially and unpopularly replaced by Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson with the Maple Leaf Flag. The Leader of the Opposition, the Rt. Hon. John Diefenbaker, derided the Liberal premier’s decision:

“We have had a flag. Flags can be changed. But flags cannot be imposed — the sacred symbols of a people’s hopes and aspirations — by the simple capricious personal choice of a prime minister of Canada. Now then, whenever the overwhelming majority of Canadian people want a new version, and when the design is meaningful and acceptable to most Canadians, that’s democracy. … I asked him [Prime Minister Pearson] this question: as to whether or not, under the circumstance, he would permit or he would arrange for a national referendum and his answer was no.”

Hail Glorious Saint Patrick

THE FEAST OF IRELAND’S patron saint is an occasion for parading if ever there was one. For this, we can send part of our thanks to the British Army, which happened to initiate the most famous St. Patrick’s Day Parade of them all, namely, New York’s. It was 1762 when a number of Irish troops in the service of the Crown took it upon themselves to parade up Gotham’s own Broadway on the 17th of March. (More recently, the Duke of Edinburgh was invited to partake in the New York parade during his 1966 visit to America). Despite the lamentable outbreak of separatist republicanism in much of Ireland, the sons of Erin continue to take the Queen’s shilling and serve proudly in Her Majesty’s forces, and true to form they are sure to mark their patron’s feast day.

Lord Glenavy

Sir James Henry Mussen Campbell, Bt., 1st Baron Glenavy, PC, QC. was born in Dublin in 1851. Campbell graduated from the University of Dublin (Trinity College) a Bachelor of the Arts in 1874. He was called to the Irish bar in 1878, being made a Queen’s Counsel in 1892.

Campbell was elected to Parliament in 1898, being called to the English bar a year later. He was made Solicitor General for Ireland in 1903, as well as being appointed an Irish Privy Counsellor. He rose to become Lord Chief Justice of Ireland in 1916, being made a baronet the following year, and Lord Chancellor of Ireland the year after that (1918). Sir James was ennobled as 1st Baron Glenavy upon relinquishing office in 1921.

Ireland was partitioned in the following year, and Lord Glenavy became the first Cathaoirleach of Seanad Éireann (Presiding officer of the Irish senate). In 1923, he chaired the judicial committee investigating the establishment of a new courts system for the Irish Free State. His proposals were implemented the following year in the Courts of Justice Act 1924, forming the Irish courts as they remain today.

Having served one six-year term in the Seanad, he did not seek re-election in 1928, and died three years later in 1931. Holding the largely honorary position of President of the College Historical Society (“the Hist”), Dublin University’s debating society, from 1925, he was succeeded upon his death by his fellow Irish Protestant, Douglas Hyde, who himself later became the first President of Ireland from 1938 until 1945.

The Men Who Saved Quebec

The British Crown’s toleration of Catholicism in Quebec was cited by the rebel colonists of the 1770’s as, ironically, an ‘intolerable act’. That the Church of Rome, that bastion of backwards conservatism and slavish hierarchy, could be tolerated in the lands under the power of the British parliament riled the Whigs—the enlightened liberal progressives of the day. Indeed, Benjamin Franklin was even so foolish as to go to Quebec as an emissary of the ‘Continental Congress’ to persuade the natives to rebel against the Crown; Congress’s proposals to ban Catholicism and prohibit the use of the French language ensured he was not successful.

The modern orthodox opinion of historians on the Quebec Act of 1774—the act that granted toleration to the Church—is that it was merely a persuasive exercise to keep les Canadiens from rebelling. A 1989 book challenged this perspective, arguing instead that a handful of British aristocrats were determined to ensure that Quebec did not become another Ireland: where Protestant ascendancy was thrust upon an unwilling nation of Catholic nobles, merchants, and peasants.

The following review by Gary Caldwell was published in a Canadian journal in 2001.

|

Philip Lawson.

The Imperial Challenge: Quebec and Britain in the Age of the American Revolution. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press. 192 pages. US$27.95. |

WHY REVIEW A BOOK published twelve years ago? I will explain. But first, let me tell you what it’s about.

When Britain took possession of Canada at the Treaty of Versailles in 1763, it faced an “imperial challenge:” how to integrate into the empire a society fundamentally different from England – in language, religion, and legal and political institutions. At the time, England was vigorously intolerant of Roman Catholicism or “popery,” the religion of its major enemies, France and Spain. British Protestantism was closely tied to the dominant Whig political ideology born of the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89. This doctrinal legacy prescribed that all British subjects were possessed of very definite and equal liberties, liberties endowed upon and limited to those who conformed to the Whig-Protestant definition of being British.

Hence the problem of 1763. English law and constitutional practice allowed only for protestant public officials and elected representatives. This meant excluding the entire French-speaking population, some 70,000 to 80,000 (the “new subjects”) as compared to some 300 Protestants established in the colony (the “old subjects”).

There were two schools of thought as to what should be done. The Whig position, favoured by much of the English political leadership and commercial class on both sides of the Atlantic, was not to accommodate the new subjects. It amounted to an attempted destruction of the local culture and to exclusion of the French-speaking population from all juridical, political and social positions, the hoped-for consequence being assimilation in one, perhaps two, generations. In short, what had been imposed in Ireland with the “protestant ascendancy.”

The opposing school of thought, still marginal in 1763, believed such a policy both impracticable and undesirable. James Murray, Lord Shelburne, Lord Dorchester (Gary Carleton), H. T. Cramahe, Alexander Wedderburn, Lord Mansfield and William Knox not only held that a Protestant ascendancy in Quebec would ruin the colony, they also believed that Quebec society was deserving of being preserved. Murray and Dorchester, who knew Quebec and its people, were adamant: the Canadians were a good “race”—in Murray’s words, “perhaps the best and bravest race on the globe” (p. 48)—and if protected they and their society would flourish and be loyal to the Crown. As it happened, all of these administrators and Crown legal officers, with the exception of Cramahe, were Anglo-Irish or Scottish; not one of them was of English origin.

But how were the Canadians and their culture to be accommodated? There were, as Lawson demonstrates, three distinct dimensions to this accommodation. The first was to respect the prevailing legal code and custom in civil and property matters; the second, to refrain from putting into place an English representative assembly because it would be the instrument of the 300 or so English and American voters in the colony. By far the most important was the third dimension, tolerance in Quebec of Roman Catholicism, which meant the nomination of a Bishop, the tithe and the right of Catholics to hold public office. Dorchester and the others successfully won these concessions in London by 1770, and they were contained in the Quebec Act in 1774, to the horror of much of English public sentiment, and especially the Americans who were more resolutely against “popery” and more Whig than the English themselves.

When Benjamin Franklin arrived in Montreal in 1775 with the invading army of the Continental Congress, he carried secret orders to ban the popish religion and the French language. Fortunately, the Americans were stopped in Quebec by no other than Dorchester, back from getting the Quebec Act through Parliament. At the head of an army of old and new subjects he broke the 1775-76 siege of Quebec.

Lawson’s interpretation is insightful in putting the events into the context of the Irish question. The major players in promoting the accommodation that became the Quebec Act had in mind “the Irish Imbroglio,” and were determined not to repeat the error of the “protestant ascendancy” in Ireland. The Quebec Act emerges clearly as the culmination of thoughtful and courageous policy formulation, a model of generous statesmanship. Hence, as Lawson goes on to argue, the “toleration” of Roman Catholicism in the Quebec Act paved the way for the British Acts of Toleration of 1778.

Lawson also helps understand why Murray, Dorchester and the others came to the conclusions they did about the Canathan problem. These men were essentially empirical conservatives who found the answer “in the past”—Quebec society as they had known it in the 1760s—and the “elastic nature of the British Constitution.” And here Lawson runs smack into the prevailing wisdom in Canadian historiography.

Lawson is insistent on the coincidental nature of any link between the Quebec Act and the American Revolution, affirming that there is no evidence that the inspiration for the Quebec Act was to placate the Canadians so as to keep them apart from the Americans. As this alleged link is one of the most tenacious myths in the Canadian historical consciousness, it is worth citing Lawson:

What can be done to dispose of this myth once and for all? Fifty years ago both Coupland and Burt said that they could find no evidence to justify such an assertion with Lanctot repeating the message in the 1960s, and nothing has yet come to light to contradict them (pp. 123-124).

When I first read this book in the early 1990s and realized how revolutionary his thesis was, I contacted Lawson to talk about his work. In passing, I mentioned that I supposed that The Imperial Challenge must have created quite a controversy in Canadian academic circles. His reply was “No, it has attracted very little attention in Canada.” (I never saw him again. I had arranged to see him a few years later, but just before I arrived in Edmonton he was admitted to hospital for terminal cancer and died shortly afterwards.) In subsequent years, I have been to McGill-Queens Press in Montreal to buy copies of his book to give to friends. Inquiring as to sales, I was told that only a few hundred copies had been sold. And, so far, I have encountered only one reference to Lawson’s book (in Yves Lamonde’s Histoire sociale des politiques au Quebec).

I was curious enough to go back recently to the reviews written when the book came out. There were 16 in Canada in French and English, in the United States and in the United Kingdom; all reviewers were quite positive except one (who wrote two of the reviews). They all commented positively on the extent and depth of the documentation, as well as the fresh reading from parliamentary debates, the personal archives of the principal players, and the press of the day. As for his interpretation of how the Quebec Act came to be, there is no suggestion that he was wrong in any respect. The negative reviewer suggests only that it is pretentious of Lawson to think he has added much to existing work on the Quebec Act. Of the 15 reviewers, a full half explicitly accredit Lawson with drawing out the intention of avoiding the error of Ireland.

Why, then, did a book, critically acclaimed by the author’s peers, which sheds considerable light on a pivotal period in the history of Quebec and Canada, drop out of sight in Quebec, and I suspect in the rest of Canada? Lawson calls into question the conventional wisdom on a very important subject in Canadian history, and no one takes notice. For instance, two prominent Canadians, Gerard Bouchard and John Raulston Saul, social thinkers who are presently reinterpreting Canadian history, make no mention, to my knowledge, of this book. A book that should have caused waves has generated scarcely a ripple.

Perhaps my assessment, as a non-professional historian, is faulty and I would welcome a demonstration of where I have erred. What are the factors that explain the untimely eclipse of Lawson’s work? Could it be simply that Canadian intellectual discourse is shallow, that a seminal work can be dropped into the water and hit bottom generating nothing more than a superficial ripple of perfunctory reviews and listings in compendiums? This is one possible explanation; a more certain explanation lies in ideology.

The ideological axe, starkly put, goes as follows. Quebec’s nationalist, republican-leaning contemporary intellectuals are loath to entertain the idea that a coterie of British Conservatives (half of them aristocrats) literally saved Quebec society by helping to keep it strong enough to withstand the renewed neo-liberal assault led by Lord Durham three quarters of a century later and, then, begin to rehabilitate the Quebec polity (under British institutions) in 1867. Such an idea being beyond the pale (again, the ghost of Ireland), they maintain the myth that the Quebec Act was political opportunism inspired by the American threat. What will it take for Quebec nationalist thinkers to recognize and appropriate the historical reality that Dorchester twice—in the Quebec Act and the siege of Quebec—saved Quebec? It is no exaggeration to assert that, had it not been for this one Anglo-Irish aristocrat, Quebec would likely have become anglicized and, subsequently, integrated into the American empire.

As for English-speaking Canada, the current crop of orthodox historians has long consigned our British imperialist past to the Marxist dust-heap of history: nothing good could possibly have come of it, all imperialisms being, by definition, bad. They are not about to disturb their orthodoxy that in contrast to Imperial Britain, which was incapable of any genuine sympathy for Quebec—only Canadian nationalist intellectuals are enlightened and respectful of Quebec society. So, they too maintain the “political opportunism” interpretation of the Quebec Act, despite its having been refuted by Lawson and his predecessors. Essentially, what we are seeing is a refusal to acknowledge a debt owed to dead white male Protestants (from Ireland and Scotland). But gratitude is not, as the contemporary French philosopher Alain Finkielkraut has pointed out, a hallmark of modern progressive thinkers.

I write this review knowing full well that it is too late for Lawson’s work to be rehabilitated. The Imperial Challenge is among the titles in this year’s McGill-Queen’s clear-the-warehouse sale.

Previously: Hitchcock in Quebec

Hitchcock in Québec

QUÉBEC, THAT STRANGE and charming province, is a most intriguing nation. It is where the British, French, and American tendencies clash and combine to form that most peculiar of all American varieties: le Québécois. Of course, since the 1960s Québec has become more French; no, not more French but more like France in that every year it plunges deeper into the depths of self-loathing: that hatred of one’s own tradition and history which has so marked out “the new Europe”. It is a race to assert one’s self by destroying any living connection to one’s past. Un jeu du fou. More’s the pity, as this once-vibrant melting pot of traditions expressed itself in interesting ways.

A splendid display of this Québec can be found in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1953 drama I Confess. The film had been recommended to me often and I finally got around to seeing it tonight. I won’t give away any of the plot, which is a good one, but Hitchcock lives up to his reputation with his excellent framing of the scenes. (Though I must admit, half of it is merely the settings in the Ville de Québec themselves). They include a peek into the Québécois Parliament. Above the Speaker’s dais is displayed not only the Sovereign’s arms, but also a crucifix, exhibiting our loyalties both temporal and spiritual. In the court room you find yet another blend of the Anglo and the French. As you no doubt recall from our handy little map, Quebec is a country with a mixed legal system. Founded as Nouvelle-France it had the civil system derived from the Romans. Captured by the British and later transformed into part of the Canadian Confederation, it has accrued layers of the Common Law so dear to we Anglos. The officials of the court wear British-style robes — the judge even has a tricorn hat — but over the jury looms a large crucifix. English government and French culture tempered by Catholic truth; not a bad mixture.

Anyhow, if you haven’t seen the film yet, here are a few snaps to enjoy until your Hitchcockian thirst is satiated. (more…)

A Sienese Gem Lost

STEALING A GLANCE at the photo above, the viewer would easily be forgiven for mistaking the vista for that of a subway entrance in turn-of-the-century Siena, Italy. The proud medieval tower lurks over a comely metal-and-glass structure of continental flavor. However the city fathers of that ancient Italian municipality never deigned to erect an underground railway. The precise locus of the vista is far removed: it is the corner of Park Avenue and 33rd Street, and the building behind the subway entrance is not the town hall of Siena, but rather the armory of the 71st Regiment, New York National Guard.

When the earlier Romanesque Revival armory of the Seventy-First Regiment burnt down in 1902, it was decided to build the new armory on the same, though slightly enlarged, site. The 1905 construction was built to the design of the architectural firm of Clinton and Russell, and was clearly inspired by the Palazzo Pubblico (the town hall, photo at right) of Siena, on that city’s Piazza de Campo. While the Seventh Regiment Armory contains the finest interiors of any military building in City, and probably the entire Empire State, the exterior of the Seventy-First’s armory was far superior. Even though the interior was not to the same lofty standard as the Seventh, it was by no means lacking, for it had all the wood-panelled rooms filled with military regalia from times gone by which one expects of New York’s armories from the period. (more…)

When the earlier Romanesque Revival armory of the Seventy-First Regiment burnt down in 1902, it was decided to build the new armory on the same, though slightly enlarged, site. The 1905 construction was built to the design of the architectural firm of Clinton and Russell, and was clearly inspired by the Palazzo Pubblico (the town hall, photo at right) of Siena, on that city’s Piazza de Campo. While the Seventh Regiment Armory contains the finest interiors of any military building in City, and probably the entire Empire State, the exterior of the Seventy-First’s armory was far superior. Even though the interior was not to the same lofty standard as the Seventh, it was by no means lacking, for it had all the wood-panelled rooms filled with military regalia from times gone by which one expects of New York’s armories from the period. (more…)

The Cardinal Duke of York

The great Marco Foppoli has designed (and very kindly passed along to me) the badge for the committee which has been assembled to commemorate the two-hundredth anniversary of the passing of the Cardinal Duke of York, or King Henry IX and I as was his style according to the Jacobite succession. I’m not entirely sure what events are being planned, but I believe there will be a conference in Rome around the anniversary in August.

Drink Audit Ale in Heaven With Me

I pray good beef and I pray good beer

This holy night of all the year,

But I pray detestable drink to them

That give no honour to Bethlehem.

May all good fellows that here agree

Drink Audit Ale in heaven with me,

And may all my enemies go to hell!

Noel! Noel! Noel! Noel!

May all my enemies go to hell!

Noel! Noel!

WITH THESE SIMPLE and lovely lines, Hilaire Belloc superbly expressed the esprit de Noël of the Christian curmudgeon. It amounts, more or less, to “Rend honor to the Holy Child, and to hell with the rest”.

His Lines for a Christmas Card are obviously meant in a jovial and light-hearted spirit (naturally, we would not wish Hell on any poor soul) and are completely intelligible but for this curious line: “May all good fellows that here agree / Drink Audit Ale in heaven with me”. What on earth is Audit Ale?

Before the Reformation, the English year was a calendar of feasts, festivals, and holidays — holy days, even. Four of these holy days, spaced fairly evenly throughout the year, were marked for such things as the collection of rents and the paying of feudal tributes. These four were Lady Day (March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation), Midsummer Day (June 24, the Feast of St. John the Baptist), Michaelmas (September 29, the Feast of St. Michael the Archangel), and Christmas (December 25, of course, the Feast of the Nativity of Christ).

Now, events such as the collection of fees and taxes and the giving of feudal tribute tend towards the dour, and so often a feudal lord would have a special ale brewed for these occasions, to ensure a certain amount of merriment among the commonfolk once their tribute had been paid and the burden lifted. This tended to be called ‘audit ale’, since it was brewed around the time of audit.

They were not, you will be happy to learn, the only seasonal brews around. There was ‘leet-ale’ for when the manorial court, or court-leet, convened, and there was Whitsun-ale for Whitsuntide, and there were church-ales which went towards the upkeep of the parish church and alms for the poor. Indeed, in village of Sygate in Norfolk, there is an inscription on the gallery of the church which reads:

And give us good ale enow . . .

Be merry and glade,

With good ale was this work made.

Also, interestingly, the very word ‘bridal’ comes not from the -al suffix English developed up from Latin, but rather from the Old English brýd-ealo: bride-ale or wedding-ale.

With the advent of Protestantism — and most especially the Puritan variant thereof — feasts, seasons, and other joviality generally became frowned-upon. England was forced to be less English, as the monotonous bores took over.

Still, remnants of the feasts and seasons remained. Lady Day was the first day of the year in Great Britain and its empire until 1752, when the Gregorian calendar was finally adopted. Similarly, the fiscal year in the United Kingdom begins on April 6 because that day in the Gregorian calendar corresponds to Lady Day in the old Julian calendar.

In Oxford and Cambridge, meanwhile, colleges still brewed special ales for the time when grades were released; either to celebrate the achievement or to soften the blow. These brews kept the old moniker of ‘audit ales’ and Belloc most likely uses the term in this derivation. Even in my own time at St Andrews we often sipped home-brewed ale from ancient, battered pewter tankards, though we rarely needed the excuse of holy days to continue the tradition.

In Oxford and Cambridge, meanwhile, colleges still brewed special ales for the time when grades were released; either to celebrate the achievement or to soften the blow. These brews kept the old moniker of ‘audit ales’ and Belloc most likely uses the term in this derivation. Even in my own time at St Andrews we often sipped home-brewed ale from ancient, battered pewter tankards, though we rarely needed the excuse of holy days to continue the tradition.

So this Yuletide perhaps you will consider home-brewing, and brew a special ale for the festal season now that the penetential time of Advent is passing. But, if you’re otherwise engaged, head into town and make sure to have a beer, and raise your pint to that Wondrous Babe whose birth brings us such mirth and cheer.

Governors Island Revisited

EVERY ONE OF THE myriad plans put forth for the ‘redevelopment’ of the venerable old Governors Island in New York Harbor has so far either stalled, been neglected, or otherwise poo-pooed. In this, we have something to rejoice. As I have often said, realistically speaking there is little that can be done to it which will not neglect or disgrace the island’s long military heritage. The officially-approved ideas put forth so far have been horrific: an amusement park, a casino, a ‘technology park’, as well as a number of other vapid proposals.

Naturally, we’d be enthused if it returned to its former role as swankiest post in the entire Army and the home of Army polo, but don’t hold your breath. West Point being the single exception, if it has even a touch of history, tradition, or class, Congress and the Department of Defense will do their best to get rid of it. After all, the National Guard has been pulled out of the Seventh Regiment Armory, the Navy has withdrawn all but a few institutions from Newport, and the Army has left the ancient Presidio of San Francisco; how long will it be until Fort Leavenworth’s foxhounds are brought out back and shot by the Monotony Monitors? (more…)

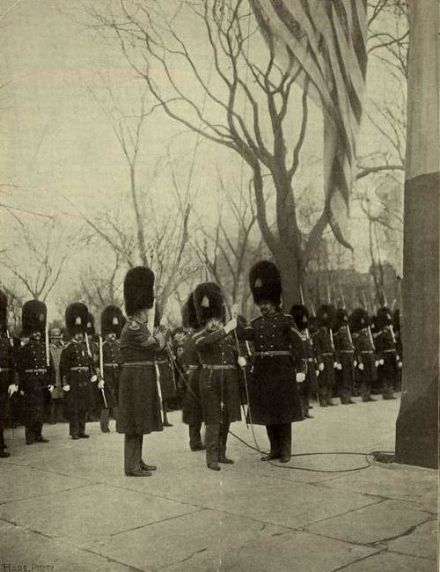

Old Guard on Governors Island

A photo of the Old Guard of the City of New York on Governors Island, with Manhattan in the background, taken on St. George’s Day, 1933. [Click here for larger photo]

Previously: Evacuation Day | Marshal Foch and the Old Guard | A New York Funeral | Old Guardsmen | The Old Guard | Grandpa

Category: New York Militaria

Evacuation Day

The Old Guard of the City of New York, raising the flag at the Battery on Evacuation Day, 1897. The day commemorates November 25, 1783, when the last royal troops left New York in accordance with the terms of the Treaty of Paris.

Old Dominion Will Receive Her Majesty

With these words spoken yesterday in the House of Lords, the Queen revealed the plans for her visit to the Commonwealth of Virginia for the upcoming celebrations surrounding the quatercentenary of the first permanent English settlement in the New World. Her Majesty is no stranger to Virginia, nor even to Jamestown, as her very first visit to the New World took place in 1957 when she attended the 350th anniversary celebrations at Jamestown. Following that 1957 official visit to the United States, the Queen opened her parliament at Ottawa for the first time since her accession to the Canadian throne. (more…)

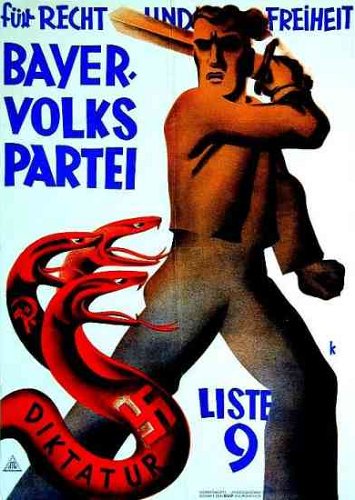

The ‘Day of Fate’

THE NINTH OF November is sometimes known in Germany as ‘Schicksalstag’ or the ‘Day of Fate’ owing to the series of events significant to modern German history which took place on the day in 1848, 1918, 1923, 1938, and 1989.

1918: Kaiser Wilhelm II is dethroned in the November Revolution, marking the end of the German monarchy.

1923: Hitler attempts his failed ‘Beer Hall Putsch’ which signficantly raises the profile of his tiny National Socialist German Workers’ Party.

1938: Synagogues and private property belonging to Jews are violently attacked in the ‘Kristallnacht’ pogrom.

1989: The politburo of Communist East Germany decides to relax the border-crossing restrictions between East and West Germany, leading to the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The first and last events (1848 and 1989) were encouraging events, while the three in between (1918, 1923, and 1938) were progressively worse. Indeed, it could easily be said that 1938 could not have happened without 1923, and that 1923 could not have happened without 1918, so these occurrences are not unrelated.

Children of a Common Mother

The 22-yard-tall Peace Arch stands between the city of Blaine in Washington state, and the city of Surrey in the province of British Columbia, demarcating the boundary between the United States of America and the Dominion of Canada. The monument, built in 1921, commemorates the 1814 Treaty of Ghent re-establishing peace between the United States and the British Empire.

Cousins

Nicholas II, Tsar of All the Russias and George V, the King Emperor.

Previously: Father & Son | Tennis, Anyone?

Poor Old Bram

ONE HAS TO FEEL A certain amount of sympathy poor old Abraham de Peyster. The city fathers, in their infinite and unending wisdom, sought fit to erect a statue of Bram in Bowling Green, the old town square of New York down at the beginning of Broadway, many moons ago. However, having set Bram very nicely upon that green, the first public park in all New York, the city fathers have of late refused to let old Heer de Peyster rest. In 1972, the park was ‘renovated’ which entailed the statue’s forced removal. He ended up four years later in Hanover Square, a quite suitable though less prominent location, where he gazed across the square towards India House. It was then that old rivalries flared anew. (more…)

James II, Our Catholic King

THIS PAST SATURDAY was the anniversary of the birth of King James II and VII of England and Scotland. The third son of Charles I, he was baptised into the Anglican church six weeks after his birth and was created Duke of York at eleven years of age. James married Anne Hyde, the daughter of the Earl of Clarendon, by whom he fathered eight children, though only two survived past childhood.

In 1664 the Duke of York equipped an expedition to relieve the Dutch of responsibility for their colonies in North America, and henceforth New Amsterdam and New Netherland were known as New York after their new Lord Proprietor.

Sometime during the year 1670 both the Duke and Duchess of York were received into the Catholic Church and stopped attending Anglican services, though the conversion did not become public knowledge until the Test Act (requiring officeholders to receive communion in a Church of England service and take an oath against Transubstantiation) was passed three years later. James was forced to renounce his offices, such as Lord High Admiral of England, though not his titles. At any rate, Anne, the Duchess of York had died in 1671 only a year after her conversion. He married Princess Maria of Modena in 1673.

The Protestant oligarchs felt threatened by the prospect of a Catholic king and thrice tried to pass laws barring James from succeeding to the throne. However his elder brother Charles II, the reigning king, dissolved parliament each time before the bill was to be passed. King Charles II died in February 1685, (having reconciled himself to the Catholic faith before his end) and thus the Duke of York was proclaimed James II of England and VII of Scotland. A private Catholic coronation was held at Whitehall Palace on April 22 before the public coronation the following day on the feast of Saint George, which was performed according to the rites of the Church of England.

James had appointed the Catholic Thomas Dongan

as Governor of New York in 1682.

The Protestant oligarchs’ fears that James would end their hegemonic grip on Scotland and England proved well-founded as in 1687 he issued a Declaration of Toleration as King of Scotland, allowing Catholics, Episcopalians, and other non-Presbyterians to hold public office and the right of public worship, and a Declaration of Indulgence as King of England removing the laws penalizing non-attendance or non-communion at Church of England services, permitting non-Anglican worship in private homes or chapels, and abolishing religious oaths for public offices. Furthermore, James had allowed Catholics to hold positions at the University of Oxford for the first time since the Protestant Revolution. More provocatively, he tried to transform Magdalen College Oxford into a Catholic seminary. He had already reckoned with the rebellion of the Duke of Monmouth who proclaimed himself king two years earlier but had been captured, tried, and executed for treason. With the birth of a Catholic son and heir, Prince James Francis Edward, in 1688 a cabal of seven Protestant nobles issued an invitation to William of Orange, the Protestant Stadtholder of the Netherlands. A few months later, William of Orange duly arrived and usurped the throne, having already married James’ daughter Mary from his first marriage. The two ruled jointly as William and Mary.

Unwilling to create a popular martyr as had happened with the executed Charles I, William allowed James to escape and fled to France where Louis XIV gave the exiled monarch the use of a palace and an ample pension. James was intent on returning to his birthright, however, and took advantage of the Irish parliament’s refusal to recognise William’s usurpation of the throne. The King landed in Ireland in March of 1689 at the head of a Franco-Irish army but was defeated by William in the famous Battle of the Boyne in July 1690, and returned to his place of exile in France.

There, Louis allowed him to live in the château of Saint-Germain-en-Laye and offered to get James elected King of Poland but James felt this would prevent any chance of a Stuart again holding the throne of England. From that time onwards, James led a simple life of penance in reparation for his sins (he had had a number of mistresses in his younger days) and finally died in 1701. He was entombed in the Chapel of St. Edmund within the English Benedictine church on the Rue St. Jacques in Paris, while his brain was sent to the Scots College in Rome, his heart to the Visitandine Convent at Chaillot, and his bowels divided between the College of St. Omer (the exiled English Catholic school, now Stonyhurst in Lancashire), and the nearby parish church of St. Germain where they remained until they were desecrated by a Revolutionary mob and lost forever. His monument at Saint-Germain, however, was rediscovered in 1824 and is proudly displayed there to this day. There is also a monument to James and the Stuarts in St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (c.f. Roma – Caput Mundi).

Aside from the pious tradition that Edward VII was received into the Church on his deathbed, James II was the last Catholic king (and as good King Edward never reigned over New York, James is even more certifiably so for us). There is a lovely coronation ode to James which I just might bring to your attention someday. But for now, reflect and remember our monarchs of old and pray that God in His mercy might grant us good Catholic rulers in stead of the shabby lot we elect today.

Old Yale Boathouse Faces Wrecking Ball

AND SO, THE ONWARD march of progress continues. Yale University’s old Adee Boathouse on New Haven harbor is to face the wrecking ball to make way for traffic improvements to the Pearl Harbor Memorial Bridge which carries Interstate 95 across the Quinnipiac River. Despite some quite extraordinary plans to physically cut the building from the shore and float it across to the opposite side of the river, it now appears that the boathouse is to be demolished. (more…)

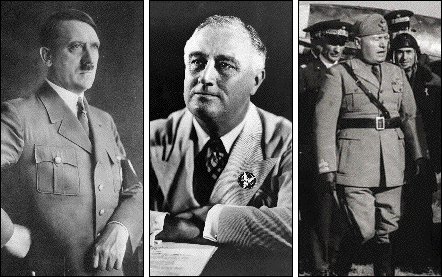

Birds of a Feather?

Were Hitler, Roosevelt, and Mussolini really just different cuts of the same cloth? In a new book, Three New Deals: Reflections on Roosevelt’s America, Mussolini’s Italy, and Hitler’s Germany, 1933-1939, Wolfgang Schivelbusch makes precisely that argument. Interestingly, the National Socialists in Germany looked with fondness towards Roosevelt’s style of rule. The Nazi party newspaper Völkischer Beobachter actually praised “the adoption of National Socialist strains of thought in his economic and social policies” while Mussolini also saw a bit of himself in FDR. Roosevelt wouldn’t give the time of day to Herr Hitler but was actually quite fond of Signor Mussolini, calling him “that admirable Italian gentleman”.

Were Hitler, Roosevelt, and Mussolini really just different cuts of the same cloth? In a new book, Three New Deals: Reflections on Roosevelt’s America, Mussolini’s Italy, and Hitler’s Germany, 1933-1939, Wolfgang Schivelbusch makes precisely that argument. Interestingly, the National Socialists in Germany looked with fondness towards Roosevelt’s style of rule. The Nazi party newspaper Völkischer Beobachter actually praised “the adoption of National Socialist strains of thought in his economic and social policies” while Mussolini also saw a bit of himself in FDR. Roosevelt wouldn’t give the time of day to Herr Hitler but was actually quite fond of Signor Mussolini, calling him “that admirable Italian gentleman”.

That there were massive differences between the three is obvious. (Mussolini and Hitler came to the brink of war over Austria, and later they both had a war with Roosevelt). Nonetheless, the similarities are worth pointing out, and David Gordon has written a review of the book over at the Ludwig von Mises Institute. Give it a read.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories