South Africa

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

‘The Splintering Rainbow’

The veteran South African journalist Rian Malan last year made a documentary for Al Jazeera on recent events in the country. It’s an interesting and well-balanced programme that presents multiple points of view. Importantly, it avoids the all-too-frequent stereotyping of the Mbeki/Zuma rivalry. It also includes a scene of Hellen Zille speaking (in English) to Stellenbosch students in the Sanlam Saal of the Neelsie.

The 45-minute documentary is available in four parts on YouTube below. (more…)

Life in the Cape

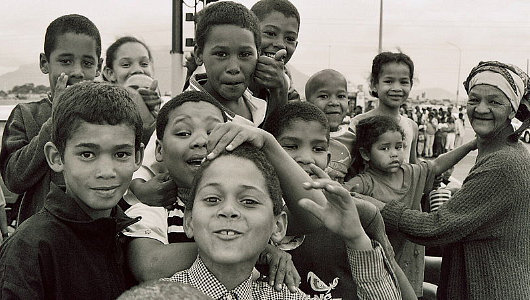

Some Selections from the Work of Photographer Bernard Bravenboer

Bernard Bravenboer is a Stellenbosch photographer whose website I stumbled across some time ago. In their vivacity and their variety, Meneer Bravenboer’s photographs capture something elemental about life in the Cape. Here are some selections from his work. (more…)

The House of Assembly

Die Volksraad

The House of Assembly (always called the Volksraad in Afrikaans, after the legislatures of the Boer republics) was South Africa’s lower chamber, and inherited the Cape House of Assembly’s debating chamber when the Cape Parliament’s home was handed over to the new Parliament of South Africa in 1910. The lower house quite soon decided to build a new addition to the building, and moved its plenary hall to the new wing. (more…)

Simon Kuper: Coloured Identity is an “Artificial, Ugly Leftover from Apartheid”

Honestly, a man like Simon Kuper should know better. The sports columnist for the Financial Times was born in Uganda, raised in the Netherlands, but both his parents are South African. In a recent article (“Apartheid casts its long dark shadow on the game”, Financial Times, 4 December 2009), Kuper discusses the racial divisions in South Africa and how they are reflected in terms of sport: White South Africans tend to gravitate towards rugby and cricket, whereas their Black compatriots overwhelmingly prefer soccer.

There exists in South Africa, however, a very large community known as the Coloureds, who are of mixed ethnic descent. Mr. Kuper, in his article, implies that they exist merely thanks to “the racial classifications of apartheid”, as if there were no Coloured people before 1948. Furthermore, he explicitly calls the difference between Coloured and Black South Africans “artificial” and an “ugly leftover from apartheid”. This is simple ignorance. He also refuses to use the word Coloured without quotation-marks, though one suspects he does not refer to Basques as “Basques”, Scots as “Scots”, Maoris as “Maoris” or so on and so forth.

The Coloureds (or kleurlinge or bruinmense in Afrikaans) are a very distinct people who form the majority of the population in the Western Cape and Northern Cape provinces. They are over four million in number and, while their distinct identity only came about after the intermarriage (and interbreeding) between the Dutch and natives after 1652, they include the genetic descendants of the old Khoisan tribes, the first people of the Cape. The Coloureds have been hugely influential in the history of the Afrikaans language, which is spoken by nine out of ten Coloured people. Just as the majority of Coloureds speak Afrikaans, the majority of Afrikaans-speakers are Coloured, not Afrikaner.

In short, Coloured people are real. They exist, and are a distinct, historical, vibrant, active culture. It is true that Coloureds are sometimes lobbed together with Zulus, Xhosa, Tswana, and others as “Black” but if one is forced to pigeon-hole them in Black-and-White terms it would be much more accurate to say either that they are both or that they are neither. Indeed, Coloureds, like Indian and White South Africans, have often faced discrimination at the hands of the ruling party, which is multi-ethnic in composition but dominated by Xhosas & Zulus in practice. The differences between Blacks and Coloureds are no more “artificial” than those between English and Irish. Mr. Kuper may want to ignore those differences (ergo, erase Coloured identity) but I say vive la différence.

Die Nuwe Kanselier

Johann Rupert is die 14de seremoniële hoof van die Universiteit van Stellenbosch

Mnr Johann Rupert, ’n afgesonderde sakeman en die seun van een van Suid-Afrika se bekendste entrepreneurs, is om die nuwe kanselier van Stellenbosch Universiteit. Dit is baie goeie nuus vir die universiteit en vir die taal, soos is mnr Rupert ’n vurige verdediger van Afrikaans. Waneer die Britse ontwerp- en leefstyltydskrif Wallpaper beskryf die taal soos “the ugliest language in the world”, Rupert — voorsitter van die Switserse luukse goedere conglomeraat Richemont — het alle advertensies vir sy groep se merken van die tydskrif verwyder. Die tydskrif het miljoene ponde in inkomste verloor, uit prominente Richemont maatskaapye soos Cartier (juweliers), Vacheron Constantin (horlosiemakers), Montblonc (penne), en Alfred Dunhill. Die Suid-Afrikaanse Akademie vir Wetenskap en Kuns, die AKTV, en ander kulturele organisasies het Rupert se optrede geondersteun.

Agtergrond van die oudste seun

Johann is die seun van die wyle entrepreneur en omgewingsbewaarder Anton Rupert, en Stellenbosch is sy tuisdorp. Hy het ook studeer ekonomie aan Stellenbosch Universiteit, wat verleen hom ‘n eredoktorsgraad in 2004. In sy vroeë jare in die sakewêreld, mnr Rupert het vir Lazard Frères in New York vir drie jaar gewerk, maar hy terug na Suid-Afrika in 1979 om Rand Merchant Bank te oprig. In 1988, Rupert stig die Compagnie Financière Richemont, en hy is nog steeds voorsitter. Ten spyte van sy rykdom, hy die soeklig vermy, en die Financial Times noem hom “reclusive”. Die selfde koerant bynaam hom “Rupert the Bear” vir sy korrek pessimistiese ekonomiese voorspellings.

’n Sterk kampvegter vir Afrikaans

Die Burger, die Kaap se koerant van rekord, sê: “Hoewel die pos van kanselier grootliks seremonieel is, kan ’n mens verwag dat iemand van Rupert se statuur en ywer ook hier sy rol op ’n vars en innoverende wyse sal vervul.”

“Sy openbare rekord as deeglike sakeman en uitsonderlike entrepreneur spreek immers vanself,” sê die koerant. “Rupert se uitmuntende sakeleierskap en visie het hom reeds verskeie toekennings op internasionale en nasionale vlak besorg. Hieronder tel Mees Invloedryke Leier in Suid-Afrika (drie keer), een van die internasionale leiers van die toekoms en handevol ander toekennings.”

“Die Burger het natuurlik sélf bande met Rupert. Hy is ’n vorige sakeleier van die jaar van dié koerant en en die Kaapstadse Sakekamer. Buite die sake-arena is Rupert ’n sterk kampvegter vir Afrikaans en is hy nou betrokke by sportontwikkeling.”

“Die mantel van kanselier val op hom in ’n tyd van besondere uitdagings aan tersiêre inrigtings. Maties self worstel met die uitdagings van transformasie en veral met die kwessie van Afrikaans as onderrigmedium. Daar kan verwag word dat Rupert ook by die US ’n sterk en rigtinggewende rol sal speel.”

NOTA VIR AFRIKAANS-SPREKENDES: Ek hoop dat u my arme grammatika sal verskoning. Dit is nie my moedertaal nie, maar ek hou van die taal.

…en dit is ’n foto van my in Suid-Afrika

A reader has pointed out that, in all my posts on South Africa, those who frequent this little corner of the web have not seen so much as a single shot of your humble & obedient scribe in that southerly land. Such lack of photographic evidence, our correspondent argues, could provoke a wealth of conspiracy theories locating me, alternatively, within the deep recesses of the Vatican, training a small fighting force in the Salzkammergut, or, somewhat implausibly, in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

(In truth, I have very, very few pictures of myself, as I am usually the one taking the pictures — some of which are electronically submitted for your approval here.)

And so, dear readers, you will find above a photograph of yours truly on one of my trips to Betty’s Bay, that splendid corner of the Cape.

Wits Scientists Unearth Afrikaans Dinosaur in the Orange Free State

Bones of “Aardonyx Celestae” on Display at the Transvaal Museum

A NEW SPECIES OF dinosaur has been discovered in South Africa by a team of researchers from the University of Witwatersrand (above, colloquially known as “Wits”), and has been given an appropriately Afrikaans moniker. The new classification of Aardonyx Celestae is a combination of Afrikaans, Greek, and Latin meaning “Celeste’s Earth-claw”, after the female team member who first handled the speciment. The 23-foot long collection of fossils was found near Bethlehem in the Orange Free State, and, after the announcement before the gentlemen of the press, the bones are now displayed at the Transvaal Museum in the South African capital of Pretoria.

The specimen discovered is about 195 million years old, dating from the Early Jurassic Period (presuming one actually doubts Ussher’s chronology). Limb proportions lead the experts to believe that Aardonyx was a biped, although its forearm bones interlock (like those of quadrupeds) suggesting that it could occasionally walk on all-fours.

Unlike most Afrikaners, though, Aardonyx was a vegetarian, taking in huge mouthfuls of vegetation through its broad jaw.

Swinging round the Cape Peninsula

Visual editor and blogger Charles Apple gives us a photographic depiction of his Saturday touring the Atlantic side of the Cape Peninsula, from the V&A Waterfront, to Green Point, Three Anchor Bay, Sea Point, Clifton, Maiden’s Cove, Camps Bay, Bakoven, the Twelve Apostles, Llandudno, Hout Bay, and Chapman’s Peak. The photos are good, but still don’t do justice to that beautiful part of the world. They do, however, get me pining for the Peninsula!

The Senate of South Africa

Die Senaat van Suid-Afrika

THE SENATE OF South Africa has had something of a tempestuous history, a fact which is attested to by the vicissitudes of the Senate chamber in the House of Parliament in Cape Town. The Senate formed the upper house of South Africa’s parliament from the unification of the country in 1910, in accordance with the proposals agreed to by Briton & Boer at the National Convention of 1908. Its members were originally selected by an electoral college consisting of the Provincial Councils of the Cape, the Transvaal, the Orange Free State, and Natal, and the members of the House of Assembly (the parliament’s lower house), along with a certain number of appointments by the Governor-General on the advice of the Prime Minister. When South Africa abolished its monarchy, the State President took over the appointing role held until then by the Governor-General, but the Senate remained largely intact until 1981, when it was abolished in advance of the foolish introduction of the 1984 constitution with its racial tricameralism.

The Senate made a brief comeback in 1994, when the interim constitution provided for a Senate composed of ninety members, ten elected by each of the provincial legislatures of the new provinces. The 1994 Senate, however, was replaced by the “National Council of Provinces” in the final 1997 constitution. (more…)

Udo & Marianna

One’s chatting on the phone in Afrikaans, the other in Finnish.

The Houses of Parliament, Cape Town

Die Parlementsgebou, Kaapstad.

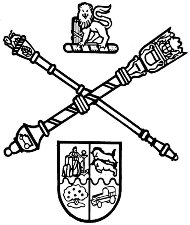

The insignia of the Parliament of South Africa, showing the Mace and Black Rod crossed between the shield and crest of the traditional arms of South Africa.

CAPE TOWN IS justifiably known as the “mother-city” of all South Africa, paying tribute to that day over three-hundred-and-fifty years ago when Jan van Riebeeck planted the tricolour of the Netherlands on the sands of the Cape of Good Hope. Numerous political transformations have taken place since that time, from the shifting tides of colonial overlords, to the united dominion of 1910, universal suffrage in 1994, and beyond. The history of self-government in South Africa has unfolded in a well-tempered, slow evolution rather than the sudden revolutions and tumults so frequent in other domains. No building has born greater witness to this long evolution than the Parliament House in Cape Town.

The British first created a legislative council for the Cape in 1835, but it was the agitation over a London proposal to transform the colony into a convict station (like Australia) that threw European Cape Town into an uproar. The proposal was defeated, but the colonists grew concerned that perhaps they were better guardians of their own affairs than the Colonial Office in far-off London. In 1853, Queen Victoria granted a parliament and constitution for the Cape of Good Hope, and the responsible government the Kaaplanders so desired was achieved. (more…)

The Nook, Stellenbosch

This place opened up in Stellenbosch just before I left South Africa, but I never had the chance to check it out. I like to look of the place, even though the colours are a bit too subdued for my taste. (more…)

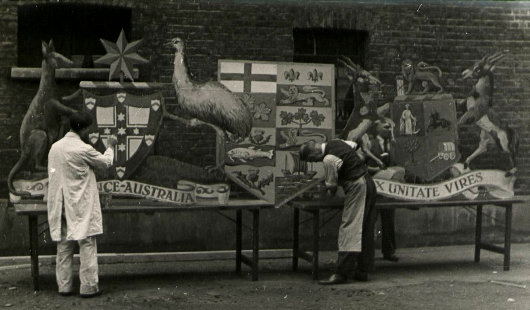

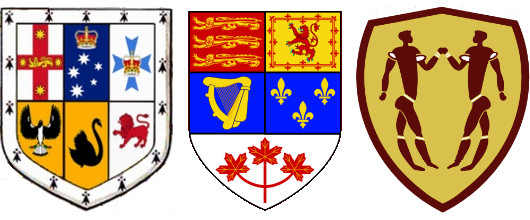

The Evolving Heraldry of the Dominions

WHAT DO THESE three coats of arms, their representations produced for the 1910 coronation, have in common? The first thing that might come to the mind of most of the heraldically-inclined is that all three are the arms of British dominions; from left to right, of Australia, Canada, and South Africa. Aside from this commonality, however, each of these three arms have been superseded.

The Australian arms above were granted in 1908, and superseded by a new grant in 1912, though the old arms survived on the Australian sixpenny piece as late as 1963. The kangaroo and emu were retained as the shield’s supporters in the new grant of arms which remains in use today.

The Confederation of Canada took place in 1867, but no arms were granted to the dominion so it used a shield with the arms of its four original provinces — Ontario, Québec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick — quartered. As the remaining colonies of British North America were admitted to Canada as provinces, their arms were added to the unofficial dominion arms, which became quite cumbersome as the number of provinces grew. A better-designed coat of arms was officially granted in 1921, and modified only slightly a number of times since then.

South Africa‘s heraldic achievement, meanwhile, was divided into quarters, each quarter representing one of the Union’s four provinces: the Cape of Good Hope, Natal, the Transvaal, and the Orange Free State. While South Africa is (like Scotland, England, Ireland, and Canada) one of the few countries to have an official heraldic authority — the Buro vir Heraldiek in Pretoria — the country’s new arms were designed by a graphic designer with little knowledge of the rules & traditions of heraldry. As a result, the design produced is unattractive and very unpopular, unlike the new South African national flag, introduced in 1994, which was designed by the State Herald, Frederick Brownell, which enjoys wide popularity and universal acceptance.

The current arms of Australia, Canada, and South Africa are represented below.

A Sad Day in Pretoria

The Proclamation of the Republic and the End of the South African Monarchy

“For every monarchy overthrown, the sky becomes less brilliant, because it loses a star,” wrote Anatole France. “A republic is ugliness set free.” South Africa’s history betrays a long struggle between monarchy and republic, most typified in the horrendous Boer War between the British Empire and the two Afrikaner republics. Many of the Boers were shocked and surprised by the leniency of the British following their surrender to the forces of the Empire, given the brutality inflicted upon the Afrikaner people by the British during the war. Their old republics became colonies but were granted the right to rule themselves within just a few years of that bitter conflict’s end. In 1910, all four British colonies — the Cape, Natal, the Orange River Colony, and the Transvaal — were consolidated in the Union of South Africa, a self-governing dominion which became an independent kingdom after the Statue of Westminster was passed in 1931.

Yet Britain’s munificence towards the defeated people could not assuage the cold-hearted bitterness formed by their cruelty during the Boer War. The term “concentration camp” first arrived in the English language in South Africa, but it was the speakers of Dutch and Afrikaans who were interned in the camps and left without rudimentary medicine or food. The photos of the interned tell the tale better than any words. When the National Party won an outright majority of seats in the South African parliament in 1948, the republican-oriented party began a gradual process of loosening the country’s ties with Great Britain. Just a year later, the Citizenship Act was passed providing for South African citizenship apart from British subjecthood. Previously, any British subject living in South Africa would be considered ‘South African’ after two years of residence. Now, it would take five years of residence for a British subject to gain South African citizenship.

In 1950, the right of appeal to the Privy Council was abolished, and the Supreme Court in Bloemfontein became the court of last instance for the country. In 1957, that court asserted the sovereignty of the Parliament of South Africa (consisting of the Crown, Senate, and House of Assembly) in its ruling over the Collins v. Donges, Minister of the Interior case. That same year the Union Jack ceased to be an official national flag alongside the oranje-blanje-blou, and “Die Stem van Suid-Afrika” was given sole official status as the national anthem; thenceforth the Union Jack and “God Save the Queen” would only be used on specifically British or Commonwealth occasions. The old Royal Navy base at Simon’s Town, founded 1806, was handed over to the South African Navy, though the Royal Navy had continued use of it under a bilateral accord. The creeping republicanism manifested itself in smaller ways too, as with “OFFICIAL” replacing the designation “O.H.M.S.” (On Her Majesty’s Service) on government correspondence. (more…)

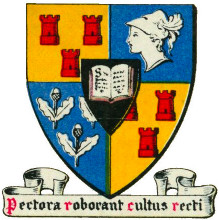

Die Wapenskild van die Universiteit

EDUCATION IN STELLENBOSCH began as early as 1685, but it wasn’t until 1866 that the Stellenbosch Gimnasium was founded. Like the (English-language) South African College in Cape Town, the Dutch/Afrikaans Gimnasium was a school covering secondary, and tertiary education. Twenty years after the foundation of the Gimnasium, it was renamed the Victoria Kollege in honour of the Queen’s jubilee of 1887. In 1918, the Parliament of South Africa finally reorganised education in the Cape, and separated both the South African College and the Victoria Kollege into their respective secondary and tertiary parts. SAC was divided into the University of Cape Town & the South African College Schools, while the Victoria Kollege was divided into the University of Stellenbosch & the Paul Roos Gymnasium.

EDUCATION IN STELLENBOSCH began as early as 1685, but it wasn’t until 1866 that the Stellenbosch Gimnasium was founded. Like the (English-language) South African College in Cape Town, the Dutch/Afrikaans Gimnasium was a school covering secondary, and tertiary education. Twenty years after the foundation of the Gimnasium, it was renamed the Victoria Kollege in honour of the Queen’s jubilee of 1887. In 1918, the Parliament of South Africa finally reorganised education in the Cape, and separated both the South African College and the Victoria Kollege into their respective secondary and tertiary parts. SAC was divided into the University of Cape Town & the South African College Schools, while the Victoria Kollege was divided into the University of Stellenbosch & the Paul Roos Gymnasium.

Along with gaining proper status as a university, the Universiteit van Stellenbosch also adopted a coat of arms in 1918. In the language of heraldry, the University’s coat of arms (or wapenskild in Afrikaans) is described as:

The “three towers gules” come from the arms of the town of Stellenbosch, and find their origin in the personal arms of Governor Simon van der Stel who founded the town in 1679. The quartering of yellow and blue (“or” and “azure”) was also inspired by van der Stel’s arms. Minerva symbolizes learning obviously, while the oak twigs represent the magnificent oak trees planted by Governor van der Stel, many of which still grace the streets of the town. The motto, Pectora roborant cultus recti, is Latin for “A sound education strengthens the spirit/character”.

Regrettably, the university tends to use its corporate logo of a stylised ‘S’ and oak leaf instead of its splendid heraldic achievement. The arms of the university can nonetheless be found around the town, displayed architecturally on numerous university buildings, in official university publications, on student clothing, and of course on the university tie.

Die Joodse nuwejaarsdag

Helen Zille looks bizarrely young in her official Rosh Hashanah greeting of 5769 (which is to say, last year).

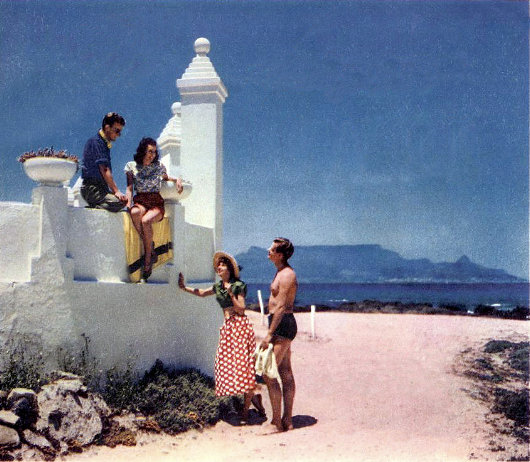

Bloubergstrand

Bloubergstrand in the 1950’s, with a view towards Table Mountain in the distance.

The End of the Affair

HOW CAN ONE possibly summarize a portion of one’s life? Those first warm breaths of African air as I stepped off the plane at Cape Town International. The stern-faced mustachioed driver who drove me to Stellenbosch, the town that became my home, on my first day on the African continent. My strongest memory is just pure sunlight. I had flown down from the deepest winter of the northern hemisphere, and the sun’s warm embrace was a welcome change. As we entered the valley of Stellenbosch, my solemn driver broke the silence and asked what business was taking me there. Learning that I came, at least in part, to study Afrikaans, his dour visage was suddenly enlivened, and he earnestly gave every assurance that I would enjoy myself in Stellenbosch immensely.

The town itself is handsome, full of white-washed walls and pleasant streets lined with old oak trees, some planted by that Dutch governor of old, Simon van der Stel. He gave the town both its name — Stellenbosch, van der Stel’s wood — and its other moniker, Eikestad, the city of oaks. The most remarkable feature of the town, however, is the beautiful range of mountains that flank it on either side. My window happened to look out on Stellenbosch mountain itself, and I admit a certain territorial feeling towards that berg has formed through the several mornings, noons, and nights it has stood watch over me.

But pleasures though there are in Stellenbosch — a stroll the Botanical Gardens, a pint at De Akker, dinner at Cognito where they know my “usual” Tanqueray-and-tonic — even more awaits the Stellenboscher who ventures further afield. I went as far as Lüderitz in Namibia, one of the furthest extremities of the old German empire. But nearby Cape Town itself provides enough to keep the ardent traveller intrigued. Table Mountain, whose looming presence over the city frames the moederstad perfectly. Further along to the pleasant sands of Clifton’s beaches, the port of Simon’s Town, and down to the end of the Cape itself — the end of Africa, where two oceans meet.

And across False Bay to Rooiels and Betty’s Bay, to the Kogelberg reserve where the hiker’s efforts are rewarded by the seclusion of a splendid little swimming hole. Floating to and fro in the little river pond, being sung to by fair Finnish maidens — there are worse ways to spend a summer’s afternoon. But it’s also glorious to be alone in Kogelberg; to hear the silence of the dead summer, outstretched arms floating along, grazing the tall grass and the heather beside the way. The open, breezy country and the quieter nooks lodged between, whose heat betrays their stillness of air. Barely any sound but the crunch of foot upon path, the wind rustling through the plants, and the odd chirp of insect here and there.

And where else? To Wupperthal, where the barefoot coloured children play happily in the eucalyptus-lined street leading to the old Rhenish mission. To Kakamas, where the farmer invites us to lunch with his family, and guides us around just a few of his 600,000 acres. To Hermanus, spending two glorious hours clearing invasive plant species from a field before breakfast — that damned Ficus rubiginosa! To Greyton for a winter’s lunch beside the fireplace, and to Genadendal, the “valley of Grace”, the queen of the Moravian missions.

And with whom? Ah, the easy acquaintances of a university town. Friends from class, friends from the pub, friends from the bistro, friends of friends, and friends of friends of friends, who all end up as friends. To the beach on Friday? The cinema tonight? The pub quiz on Tuesday? A coffee tomorrow afternoon?

The people, more than anything, make the deepest impression — both the South Africans and my fellow travellers. Good times shared and conversations enjoyed. Some surprising friendships spring forth from the unlikeliest of places and the most scant of connections. And stories are shared of varying experiences. Poor Ralf almost getting done in by that hippo in the Kalahari! The intervarsity match — another victory for die Maties. And the second test match against the Lions — Morne Steyn, that kick! A genial cup of tea in a well-kept house in Oranjezicht as the resident explains how many times she’s been burgled. The Kayamandi girl whose father disappeared long ago, whose stepfather abuses her every night, and whose mother is entrapped into acquiescence by poverty. A student dies from swine flu — a first in South Africa. Another is murdered by the obsessed friend of her older brother. The police beat the suspect so badly he cannot appear in court. The headline in the Eikestadnuus proclaims “Vyfteen weeks, vyfteen moorde” — fifteen weeks, fifteen murders in this pleasant little corner of the Cape. The latest exhausted statement from Kapt. Aubrey Marais of the Stellenbosch police. An email from the university rector: male students are reminded not to allow girls to walk home unaccompanied at night. In the face of all this, ordinary lives continue unintimidated.

This country has a tendency to seep into the veins, to get under people’s skin. There is no brief affair with South Africa. Her own sons and daughters dot the globe — thousands are in London alone — but they earn their keep abroad while they yearn for the land they left. (“They just miss having servants” half-jokes the farmer’s wife.) Some do leave forever, but many more come home after a few years. My time is up, I leave South Africa today, but I can’t help but think the affair is not over, even if it only continues from afar. It is difficult to escape the lure of this deeply troubled, deeply blessed land.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Gellner’s Prague December 19, 2024

- Monsieur Bayrou December 18, 2024

- Dempsey Heiner, Art Critic December 17, 2024

- Vote AR December 16, 2024

- Articles of Note: 12 December 2024 December 12, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories