Quotations

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution

There is a wonderful glimpse of the old days in the memoirs of the late Lord Waddington (1929-2017).

David Waddington was a Lancashire man who became a lawyer, Member of Parliament, Government Chief Whip, Home Secretary, peer of the realm, and eventually Governor of Bermuda. (In that final role, he was the last of the big dogs — all the ones since have been civil servants.)

The old British constitution — before New Labour’s ill-judged reforms — had a lithe efficiency in those days aptly reflected in quite how few people were employed by the highest court in the realm — and how unfussedly they were officed:

I had only been in the House for two days when I received a telephone call from the clerk of my Manchester chambers asking me if later in the week I was prepared to sit as a deputy County Court judge somewhere in London. This would allow my colleague Bob Hardy, who had contracted with the Lord Chancellor’s Department, to sit as a judge on that day, to take over a brief of mine, a libel action in Leeds.

At the eleventh hour someone pointed out that if I were to sit, my career as an MP would come to an abrupt end because as a result of the House of Commons Disqualification Act I would have disqualified myself from membership of the House, thereby precipitating another by-election. I was then begged by Bob to go and explain to the lady in the Lord Chancellor’s Department why he could not sit and why I had turned out to be an inappropriate replacement.

I set off and, after journeying along many corridors and ascending and descending many staircases, I eventually found a little old lady sitting alone in a tiny office at the bottom of a gloomy stairwell somewhere in the bowels of the House of Lords.

I apologised for troubling her and she said: ‘I can assure you it is no trouble. In fact I am delighted to see you. I have been in this office for thirty-five years and you are the first person who has ever visited me.’

Equality

I find that they’re not true without looking further than myself. I don’t deserve a share in governing a hen-roost, much less a nation. Nor do most people — all the people who believe advertisements, and think in catchwords, and spread rumours. The real reason for democracy is just the reverse. Mankind is so fallen that no man can be trusted with unchecked power over his fellows. Aristotle said that some people were only fit to be slaves. I do not contradict him. But I reject slavery because I see no men fit to be masters.

This introduces a view of equality rather different from that in which we have been trained. I do not think that equality is one of those things (like wisdom or happiness) which are good simply in themselves and for their own sakes. I think it is in the same class as medicine, which is good because we are ill, or clothes which are good because we are no longer innocent. I don’t think the old authority in kings, priests, husbands, or fathers, and the old obedience in subjects, laymen, wives, and sons, was in itself a degrading or evil thing at all. I think it was intrinsically as good and beautiful as the nakedness of Adam and Eve. It was rightly taken away because men became bad and abused it. To attempt to restore it now would be the same error as that of the Nudists. Legal and economic equality are absolutely necessary remedies for the Fall, and protection against cruelty.

But medicine is not good. There is no spiritual sustenance in flat equality. It is a dim recognition of this fact which makes much of our political propaganda sound so thin. We are trying to be enraptured by something which is merely the negative condition of the good life. And that is why the imagination of people is so easily captured by appeals to the craving for inequality, whether in a romantic form of films about loyal courtiers or in the brutal form of Nazi ideology. The tempter always works on some real weakness in our own system of values: offers food to some need which we have starved.

When equality is treated not as a medicine or a safety-gadget but as an ideal we begin to breed that stunted and envious sort of mind which hates all superiority. That mind is the special disease of democracy, as cruelty and servility are the special diseases of privileged societies. It will kill us all if it grows unchecked. The man who cannot conceive a joyful and loyal obedience on the one hand, nor an unembarrassed and noble acceptance of that obedience on the other, the man who has never even wanted to kneel or to bow, is a prosaic barbarian. But it would be wicked folly to restore these old inequalities on the legal or external plane. Their proper place is elsewhere.

We must wear clothes since the Fall. Yes, but inside, under what Milton called “these troublesome disguises,” we want the naked body, that is, the real body, to be alive. We want it, on proper occasions, to appear: in the marriage-chamber, in the public privacy of a men’s bathing-place, and (of course) when any medical or other emergency demands. In the same way, under the necessary outer covering of legal equality, the whole hierarchical dance and harmony of our deep and joyously accepted spiritual inequalities should be alive. It is there, of course, in our life as Christians: there, as laymen, we can obey — all the more because the priest has no authority over us on the political level. It is there in our relation to parents and teachers — all the more because it is now a willed and wholly spiritual reverence. It should be there also in marriage.

This last point needs a little plain speaking. Men have so horribly abused their power over women in the past that to wives, of all people, equality is in danger of appearing as an ideal. But Mrs. Naomi Mitchison has laid her finger on the real point. Have as much equality as’ you please — the more the better — in our marriage laws: but at some level consent to inequality, nay, delight in inequality, is an erotic necessity. Mrs. Mitchison speaks of women so fostered on a defiant idea of equality that the mere sensation of the male embrace rouses an undercurrent of resentment. Marriages are thus shipwrecked. This is the tragi-comedy of the modern woman; taught by Freud to consider the act of love the most important thing in life, and then inhibited by feminism from that internal surrender which alone can make it a complete emotional success. Merely for the sake of her own erotic pleasure, to go no further, some degree of obedience and humility seems to be (normally) necessary on the woman’s part.

The error here has been to assimilate all forms of affection to that special form we call friendship. It indeed does imply equality. But it is quite different from the various loves within the same household. Friends are not primarily absorbed in each other. It is when we are doing things together that friendship springs up— painting, sailing ships, praying, philosophising, fighting shoulder to shoulder. Friends work in the same direction. Lovers look at each other: that is, in opposite directions. To transfer bodily all that belongs to one relationship into the other is blundering.

We Britons should rejoice that we have contrived to reach much legal democracy (we still need more of the economic) without losing our ceremonial Monarchy. For there, right in the midst of our lives, is that which satisfies the craving for inequality, and acts as a permanent reminder that medicine is not food. Hence a man’s reaction to Monarchy is a kind of test. Monarchy can easily be “debunked”; but watch the faces, mark well the accents, of the debunkers. These are the men whose tap-root in Eden has been cut: whom no rumour of the polyphony, the dance, can reach — men to whom pebbles laid in a row are more beautiful than an arch. Yet even if they desire mere equality they cannot reach it. Where men are forbidden to honour a king they honour millionaires, athletes, or film-stars instead: even famous prostitutes or gangsters. For spiritual nature, like bodily nature, will be served; deny it food and it will gobble poison.

And that is why this whole question is of practical importance. Every intrusion of the spirit that says “I’m as good as you” into our personal and spiritual life is to be resisted just as jealously as every intrusion of bureaucracy or privilege into our politics. Hierarchy within can alone preserve egalitarianism without. Romantic attacks on democracy will come again. We shall never be safe unless we already understand in our hearts all that the anti-democrats can say, and have provided for it better than they. Human nature will not permanently endure flat equality if it is extended from its proper political field into the more real, more concrete fields within. Let us wear equality; but let us undress every night.

Election Day

While in the outer world the British people have been electing as their representatives, by the degrading process of universal suffrage, several hundred paid professional politicians, few of them owners of landed property, many of them positively base-born, in the closed world of this column a very different ceremony has been taking place.

In the dark, time-worn Gothic Hall of Assembly, amid crumbling tombs and carved symbols whose inmost meaning few can now read, the Great Feudatories of the Realm have been swearing fealty to the Regent, settling on their broad shoulders once more, for another year, the dreaming loads of Church and State.

In a thousand manors too, throughout the column, the Lesser Feudatories have been receiving the allegiance of village headmen bearing baskets of eggs, indigenous stones and symbolic flowers, of representatives of the craft-guilds – wood-carvers, arquebus-designers and organ-builders prominent as ever – and tenant farmers and yeomen, red-cheeked, bucolic figures in their holiday coats of decent frieze.

After these day-long, solemn ceremonies, rituals so intricate that none but the columnar heralds can understand them, high and low, through all their exact, foreknown, immutable degrees from the Regent to the humblest labourer, feel themselves united, confirmed once more, as the mighty order of society is confirmed.

In the outer world all is ephemeral, unstable, eddying and whirling this way and that in ceaseless, unreasonable change. Within, all is unchanging and unchangeable. As it was, as it is, as it will be, till Judgment Day.

Regnum, Ecclesia, Studium

The threefold division of the world

As such he might be expected to have ideas about the idea of a university, and he wrote about them in The Spectator in August 1983.

Mister Grimond (as he still was then, only just), suggested those interested in the subject “might turn to a lecture by Ronald Cant, sometime Reader in Scottish History in the University of St Andrews”:

[…]

A vital aspect of this tripartite organisation, as Cant says, was that each should serve and support the other. But the studium, while interacting with the regnum and ecclesia, must maintain its independence.

It was certainly the business of the studium to advance knowledge, but that was not to be the end of the matter. Knowledge was linked to public service. The learned man had a duty to the community as well as a right to pursue his intellectual quarry. In fact he pursued the quarry on behalf of the community.

The tripartite division of the world, although old-fashioned, seems to me a useful concept, emphasising that government, morality, and higher education are separate but intertwined.

It seems to me that if we expel the regnum and the ecclesia utterly from the world of the university we shall end up paradoxically with universities totally dependent upon the state… but as subservient as those in Rome.

The liberal spirit gave birth and sustenance to universities; if its progeny does not foster it in the regnum they may indeed end up as purely vocational colleges.

De Gaulle on the Market

It forces people to stretch themselves, it gives a bonus to the best, it encourages you to surpass others and to surpass yourself.

But, at the same time, it creates injustices, it establishes monopolies, it favours cheaters.

So don’t be blind to the market. You should not imagine that it will solve every problem on its own.

The market is not above the nation and the state. It is the nation, it is the state which must oversee the market. »

Three Bedrooms in Manhattan

Helena at Bethlehem

He sent along this passage from Waugh’s novel Helena in which the saint (and mother of the Emperor Constantine) arrives at Bethlehem, the city of Our Saviour’s birth, on the very feast of the Epiphany. She addresses the Magi in prayer.

“Like me,” she said to them, “you were late in coming. The shepherds were here long before; even the cattle. They had joined the chorus of angels before you were on your way. For you the primordial discipline of the heavens was relaxed and a new defiant light blazed among the disconcerted stars.

“How laboriously you came, taking sights and calculations, where the shepherds had run barefoot! How odd you looked on the road, attended by what outlandish liveries, laden with such preposterous gifts!

“You came at length to the final stage of your pilgrimage and the great star stood still above you. What did you do? You stopped to call on King Herod. Deadly exchange of compliments in which there began that unended war of mobs and magistrates against the innocent!

“Yet you came, and were not turned away. You too found room at the manger. Your gifts were not needed, but they were accepted and put carefully by, for they were brought with love. In that new order of charity that had just come to life there was room for you too. You were not lower in the eyes of the holy family than the ox or the ass.

“You are my especial patrons,” said Helena, “and patrons of all late-comers, of all who have had a tedious journey to make to the truth, of all who are confused with knowledge and speculation, of all who through politeness make themselves partners in guilt, of all who stand in danger by reason of their talents.

“Dear cousins, pray for me,” said Helena, “and for [the generally believed still unbaptized Emperor Constantine] my poor overloaded son. May he, too, before the end find kneeling-space in the straw. Pray for the great, lest they perish utterly. And pray for… the souls of my wild, blind ancestors…

“For His sake who did not reject your curious gifts, pray always for the learned, the oblique, the delicate. Let them not be quite forgotten at the Throne of God when the simple come into their kingdom.”

Problems and Solutions

There are in some periods problems to which no solutions exist.”

How to deal with ‘Direct Action’

A lesson from the experienced generation of not so long ago

BRITONS have a habit of being slow to move initially but they do get their act in order sooner or later — and usually in time to prevent disaster. Many in the metrop. have been damned irritated that the police seemed impotent when the fascist death cult “Extinction Rebellion” first reared its ugly head.

“XR” prevented working-class Londoners from getting to work on the Underground and seized bridges to publicise their claim that — despite global agricultural yields being higher than ever before in human history — we are somehow all going to be starving in a few years’ time due to “climate catastrophe”.

Nonetheless, having returned from Guernsey this morning, I find the streets of London pleasantly filled with the flying squads of the Metropolitan Police. The boys in blue are moving about in rapid response units, ready to deploy immediately whenever and wherever the Extincto-Nazis rear their ugly heads, thus keeping the streets open to all comers (bar those with nefarious designs of un-civic disorder).

“XR” are not the first to threaten (nor to deliver) “direct action”, but I was heartened when a friend shared this splendid example of how to deal with irate students allegedly delivered by the Warden and Fellows of Wadham College, Oxford, in 1968:

Dear Gentlemen,

We note your threat to take what you call ‘direct action’ unless your demands are immediately met.

We feel it is only sporting to remind you that our governing body includes three experts in chemical warfare, two ex-commandos skilled with dynamite and torturing prisoners, four qualified marksmen in both small arms and rifles, two ex-artillerymen, one holder of the Victoria Cross, four karate experts and a chaplain.

The governing body has authorized me to tell you that we look forward with confidence to what you call a ‘confrontation,’ and I may say, with anticipation.

This was less than a quarter-century after the victory of the Second World War, so Wadham could call upon an experienced gang to fill the ranks of its fellowship in those days.

I suppose Maurice Bowra was Warden of Wadham at this time. While a renowned buggerer, he did manage to die with a knighthood, a CH, and the Pour le Mérite (civil class) — which is not a bad innings all things considered.

‘Apostle of a Monstrous Trinity’

Hammerstein’s Four Types

Speaking to a friend the other day, I mentioned this quotation which is often incorrectly attributed to Rommel (including by me).

The actual source of these words is Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord, a four-star general of the German army, who described the four types of officer and their place along the axes of being 1) either clever or stupid, and 2) either hardworking or lazy.

There are clever, hardworking, stupid, and lazy officers. Usually two characteristics are combined.

Some are clever and hardworking; their place is the General Staff.

The next ones are stupid and lazy; they make up ninety percent of every army and are suited to routine duties.

Anyone who is both clever and lazy is qualified for the highest leadership duties, because he possesses the mental clarity and strength of nerve necessary for difficult decisions.

One must beware of anyone who is both stupid and hardworking; he must not be entrusted with any responsibility because he will always only cause damage.”

I am sure the experience of many would confirm that Hammerstein’s typology is also applicable in the civilian world.

Hammerstein was a brave man, who unsuccessfully attempted to see President Hindenburg personally in the hopes he would intervene to stop the massacre on the Night of Long Knives.

His friend and regimental comrade General Kurt von Schleicher, the last Chancellor of Germany before Hitler’s appointment, was among those murdered on the evening and Hammerstein defied army orders by attempting to attend Schleicher’s funeral only to be stopped by the SS.

His friend and regimental comrade General Kurt von Schleicher, the last Chancellor of Germany before Hitler’s appointment, was among those murdered on the evening and Hammerstein defied army orders by attempting to attend Schleicher’s funeral only to be stopped by the SS.

Nonetheless, his reputation and skill ensured he was given command during the war, although Hitler later personally dismissed him for his opposition to national socialism.

As Hammerstein was dying of cancer in 1943 he told the art historian Udo von Alvensleben-Wittenmoor: “I am ashamed to have belonged to an army that witnessed and tolerated so many crimes”.

His family refused to allow Hammerstein to be buried with a military funeral as it would have meant his remains being draped in the swastika flag.

Despite being a conservative Protestant nobleman of the old school, two of his five children ended up as communists, though his youngest son became a Protestant theologian.

Portugal in the 1950s

I felt as if I were going from a noisome prison out into the morning air in the countryside. … After the clangor and tension [of New York], and so many faces taut or ugly or vicious, life in Portugal might be unaffluent but it was still quiet, still kindly, still human. The lack of development and the poverty struck one as a blessing. The absense of advertisers and of mass media men and of vote-catching politicians, bawling out their meretricious wares, was like relief from the presence of the demented.

via R.J. Stove

“Nothing between the insulting and the superlative…”

« In the restaurant on the Rue Saint-Augustin, M. Mirande would dazzle his juniors, French and American, by dispatching a lunch of raw Bayonne ham and fresh figs, a hot sausage in crust, spindles of filleted pike in a rich rose sauce Nantua, a leg of lamb larded with anchovies, artichokes on a pedestal of foie gras, and four or five kinds of cheese, with a good bottle of Bordeaux and one of champagne, after which he would call for the Armagnac and remind Madame to have ready for dinner the larks and ortolans she had promised him, with a few langoustes and a turbot — and, of course, a fine civet made from the marcassin, or young wild boar, that the lover of the leading lady in his current production had sent up from his estate in the Sologne.

“And while I think of it,” I once heard him say, “we haven’t had any woodcock for days, or truffles baked in the ashes, and the cellar is becoming a disgrace — no more ’34s and hardly any ’37s. Last week, I had to offer my publisher a bottle that was far too good for him, simply because there was nothing between the insulting and the superlative.” »

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg

« I ceased in the year 1764 to believe that one can convince one’s opponents with arguments printed in books. It is not to do that, therefore, that I have taken up my pen, but merely so as to annoy them, and to bestow strength and courage on those on our own side, and to make it known to the others that they have not convinced us. »

« I ceased in the year 1764 to believe that one can convince one’s opponents with arguments printed in books. It is not to do that, therefore, that I have taken up my pen, but merely so as to annoy them, and to bestow strength and courage on those on our own side, and to make it known to the others that they have not convinced us. »Metternich: Ex Ordine Libertas

Fürst von Metternich-Winneberg-Beilstein

From the memoirs of Miklos Banffy

« After getting home I must admit that I slept soundly, although occasionally, when still half-asleep, I seemed to hear more rumbling of heavy lorries passing under my windows than on previous nights. However, since the street outside was the habitual route for deliveries to the market halls nearby, and the market cars had always rattled past noisily long before dawn, it did not seem to be different from any other night in the year.

It was only later that I heard what had happened early that morning. When my old valet called me he announced three things: my bath had been prepared, revolution had broken out, and Count Mihály Károlyi was now Minister-President. »

Pink champagne & civil war

In “Neither a Lender Nor a Borrower Be” from the October New English Review, Theodore Dalrymple discusses his own first-hand encounter with the lending crisis:

With a large loan outstanding, I continued to receive, about every month or so, offers of a further loan of $50,000, no questions asked and mine for the borrowing by mere telephone call, just in case there were any little extras or extravagances I happened to feel like treating myself to (but apply now, before next month’s offer of precisely the same thing!). The principal example given of the little extras or extravagances to which I might want to treat myself was the holiday of a lifetime.

Two considerations led me to turn down all these kind offers. The first is that my taste in holidays of a lifetime runs more to observing civil wars than to lolling in the lap of luxury, and while sometimes expensive to go to, civil wars offer little in the way of sybaritic possibilities (though there was a surprising availability of pink champagne during the Liberian civil war, even if it was difficult to chill).

Words of Windisch-Grätz Wisdom

Prince of Windisch-Grätz

on the liberal constitutionalist rebels

Mussolini (in his own words)

A Selection of Quotations from Il Duce

“The Socialists ask us for our program?

Our program is to smash the heads of the Socialists.”

Mussolini himself had been a very prominent Socialist, working for leftist newspapers and was even once deported from Italy when his anti-Catholicism and anti-royalism became too much for the authorities to handle. (more…)

Republicanism is a traitor’s game

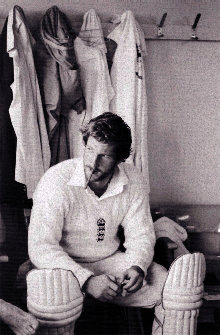

I listen to all these republicans…

If it was down to me I’d hang ’em! I honestly would. It’s a traitor’s game for me.”

SO SPEAKETH Sir Ian Botham, on this occasion to the Guardian, the newspaper of the British ruling class. It’s always reassuring when a public figure speaks out in support of the few remnants of tradition the metropolitan elites allow us to retain, so Sir Ian deserves a firm handshake, a pat on the back, and a pint on the house. Still, there are others (poor souls!) who disagree with the goodly knight. Herein the British Republican movement lists its supporters. They are mostly relative unknowns, except for the former Viscount Stansgate and the rather vulgar Peter Tatchell.

Leanne Wood, a member of the Welsh Assembly, states “I am a republican because I am opposed to the hereditary system”. Opposed to the hereditary system? We presume, therefore, that when she reaches the evening of her years (after a long life sucking off the taxpayer teat) she will not leave her comfortable residence and all her earthly possessions to her offspring, but instead donate them to the Fabian Society. Pity her poor children!

“I believe,” Ms. Wood continues, “in equality not patronage”. To my mind, party politics is more often a source of patronage than the limited constitutional monarchy. As for equality, doesn’t being a member of the Welsh Assembly give her more power and influence than others? Not very egalitarian, but then there are no true egalitarians. Only some who, rather than appreciating the heights of Western civilization, prefer to topple it to the ground in order to establish greater “equality”.

The former Viscount Stansgate, who currently styles himself “Tony” Benn, proclaims that “In a democracy people must be able to elect their own head of state”. The demos beg to differ. The Crown has consulted the people in forty-four different general elections since the enactment of the Reform Act of 1832, and yet the voters have curiously neglected to ever vote a republican party into government.

Mr. Tatchell, meanwhile — whom the Republican movement identifies as a “gay rights and human rights campaigner” (I am glad they concede the dissimilarity in the two concepts) — tells us that “Britain remains a partial, incomplete democracy, steeped in aristocratic privilege.” Hear! Hear! “Why can’t we have a complete, mature democracy,” Mr. Tatchell asks, “where the people elect our Head of State?” Perhaps because democracies which elect their head of state are rarely mature. It seems entirely more mature to keep those institutions which have stood the test of time rather than to arbitrarily destroy them based on what amounts to little more than modish management concepts.

Curiously, at least three people on the Republican movement’s list of supporters are Queen’s Counsel (QCs, or “silks”). They are not so opposed to the monarchy as to refuse the fruits of its munificence, and for that we should praise their pragmatism. Even more curiously, however, nineteen on the list are Members of Parliament. Surely MPs are required to take an Oath of Loyalty to the Crown in order to take their seats? But then perhaps these nineteen are abstentionists along the lines of the Sinn Féiners. While one hesitates to presume to advise the Crown, it might be useful every so often to inquire among the members of Parliament as to which would lend their votes to the abolition of the monarchy, and then deal with them in the manner Sir Ian Botham profers.

“If it was down to me I’d hang ’em!”

Category: Monarchy | Hat tip: The Monarchist.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories