Featured

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Begley Takes to the Skies

Brave Bear Skydives in Support of Hammersmith’s Irish Cultural Centre

The Irish Cultural Centre in Hammersmith, London is in danger of closing as its landlord, the local council, is putting the ICC’s building up for sale. The enterprising folk at the Centre have launched the Wear Your Heart for Irish Arts campaign to raise the funds required to save this outpost of Gaelry and have adopted Begley the Bear as the campaign mascot. Begley is a brave little lad and he recently undertook a charity skydive to raise money for the Centre.

Alright, he wasn’t so brave at first, but he worked up the courage in time.

The ICC’s assistant manager, Kelly O’Connor, accompanied Begley on his endeavour.

She had to cover poor Begley’s eyes at the start…

…but then they got into the swing of things.

And at the end of the day, who could say no to a pint of plain?

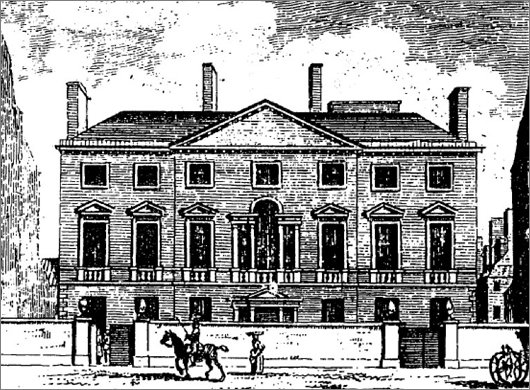

The Old In & Out

Cambridge House, Number Ninety-four, Piccadilly

ON MY WAY TO the Cavalry & Guards Club yesterday for lunch with an ancient veteran of King’s African Rifles (“Hardly qualify for this place — Black infantry!”) I realised I was a bit ahead of schedule and so took a gander at Cambridge House, the former home of the Naval & Military Club on Piccadilly. It’s surprising that an eighteenth-century grand townhouse of this kind has sat in the middle of the capital completely neglected, unused, and falling apart for over a decade.

The Inauguration of the President of Ireland

PRESIDENTIAL inaugurations in Ireland were once grand affairs. Viceroys and Governors-General were installed with comparatively little ceremony, the last to hold the latter office having been sworn into office in his brother’s sitting room. Ireland first gained a president in 1938 in accordance with the Constitution adopted at the end of the previous year. (Somewhat awkwardly, Ireland had both a King and a President from 1938 until 1949).

The first President of Ireland was known as An Craoibhín Aoibhinn — “The Pleasant Little Branch” — or Douglas Hyde to give his proper name. An ancient professor whose upper lip was enhanced by a bushy moustache, Prof. Hyde founded Conradh na Gaeilge, the league for the preservation and promotion of the Irish language whose headquarters on Harcourt Street — sorry, I mean Sráid Fhearchair — are just a few doors down from the birthplace of Edward Carson. The Times of London reported thus on Dr. Hyde’s inauguration day:

In the morning he attended a service in St Patrick’s Cathedral presided over by the [Protestant] Archbishop of Dublin, Dr. Gregg. Mr. de Valera and his Ministerial colleagues attended a solemn Votive Mass in the [Catholic] Pro-cathedral, and there were services in the principal Presbyterian and Methodist churches, as well as in the synagogue.

Dr. Hyde was installed formally in Dublin Castle, where the seals of office were handed over by the Chief Justice. Some 200 persons were present, including the heads of the Judiciary and the chief dignitaries of the Churches. After the ceremony President Hyde drove in procession through the beflagged streets. The procession halted for two minutes outside the General Post Office to pay homage to the memory of the men who fell in the Easter Week rebellion of 1916. Large crowds lined the streets from the Castle to the Vice-Regal Lodge and the President was welcomed with bursts of cheering. …

In the evening there was a ceremony in Dublin Castle which was without precedent in Irish history. Mr. and Mrs. de Valera received about 1,500 guests at a reception in honour of the President. The reception was held in St Patrick’s Hall, where the banners of the Knights of St. Patrick are still hung. The attendance included all the members of the Dail and Senate with their ladies, members of the Judiciary and the chiefs of the Civil Service, Dr. Paschal Robinson, the Papal Nuncio at the head of the Diplomatic Corps, several Roman Catholic Bishops, the Primate of All Ireland, the Archbishop of Dublin, the Bishop of Killaloe, the heads of the Presbyterian and Methodist congregations, the Provost and Vice Provost of Trinity College, and the President of the National University.

It was the most colourful event that has been held in Dublin since the inauguration of the new order in Ireland, and the gathering, representing as it did every shade of political, religious, and social opinion in Éire, might be regarded as a microcosm of the new Ireland.

These days much remains the same, though much has also changed. The tradition of Mass and other religious services before the inauguration was dropped in the 1980s when an “inter-faith” service was incorporated into the ceremony itself. Dress remained formal all the way up until the 1997 inauguration of Mary McAleese. The President’s husband, who despised all formal dress, displayed a disgraceful egotism by forbidding them from the ceremony. Gone the morning dress, gone the judges robes and wigs, gone the dignity of the occasion. “Business suits” were the order of the day, and remain so.

Thankfully the ceremony still takes place in St. Patrick’s Hall, the great chamber of the State Apartments in Dublin Castle. Regrettably, in the 1990s the walls of the hall were lined with French silk in a completely inappropriate shade of dark blue. It gives the unfortunate impression of a New Jersey mobster’s dining room to what would otherwise be a very dignified and stately hall. A light shade of Georgian blue would be much more appropriate.

The new president, Michael D. Higgins, is a man of diminutive stature. While one regrets he does not enjoy the correct opinion on most things, he is at least old, and so will bring, one hopes, a certain reflective maturity to the office. The mere sight of him reminds me of my childhood in the 1990s, when the now-President was in the news as culture minister during the ‘Rainbow Coalition’ and the Saw Doctors came out with the song “Michael D. Rockin’ in the Dail for Us”.

The interfaith segment this time was a combination of the truly cringe-worthy and the commendable: an absolute murdering of Be Thou My Vision, prayers and readings from the Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, the Protestant Archbishop of Dublin, a musical rendering of St Patrick’s Breastplate that I actually enjoyed but which seemed more appropriate for a film soundtrack than this event, the Gospel read by the head of the Methodist Church, including the Beatitudes read out by a panoply of multi-culti figures (e.g. a Sino-Irish schoolgirl, a bare-armed deaf woman, a charming African woman in traditional attire, an American man with emotive enunciation in the style of the Evangelical churches). Then the Lord’s Prayer in Irish, a prayer from the moderator of the Presbyterian Church, another from a Quaker woman, and another from a Coptic priest.

Oh mercy, then the cringe-ometer broke with the singing of Make me a Channel of Your Peace. The mayors in their chains of office were markedly unenthusiastic. A reading from the Koran, and a Muslim prayer, followed by the representative of the Humanist Association of Ireland, who looked like she was on some happy-happy pills, read a statement astounding in its vacuousness. Then a musical interlude. Then Enda Kenny spoke, which is always a trial to sit through. (I admit I watched the ceremony later in the day via RTE Player, so I managed to skip that bit).

Eventually, having passed through this penitential trial, there was the actual inauguration itself. The Chief Justice — robeless, pace old Mr. (now Sen.) McAleese — administered the Oath as Gaeilge, which the new president then signed (above). The necessary exercises having taken place, the Chief Justice then handed over the Seal of the President of Ireland (below).

I’ll admit one of the things I hate is how events these days take place for the photographs. In days of yore, events simply took place. A painting or engraving or drawing could be done later, and everything would look grand, whether it was or it wasn’t. Nowadays, the Chief Justice can’t just hand over the seal to the President, she has to hand it over and everyone looks at the camera and smiles. This will be banned when the Counter-Revolution comes! St. Patrick’s Hall will become like those Transylvanian peasant dance halls, where anyone who smiled was expelled, never to be admitted again.

An tUachtarain then graced us with a few words of wisdom.

Then came the more fun bit: the presidential review of the troops.

One has to appreciate a nice bit of military pomp, especially in the stately courtyard of the Castle.

Finally (below), the President & First Lady greeted a crowd of schoolchildren, many of them waving the blue Presidential Standard, before being driven off to Áras an Uachtaráin, the presidential palace in Phoenix Park.

Well, as I said on Twitter: Best of luck to Michael D. Higgins, Uachtarán na hÉireann. Not my first choice, but hope he does the country proud regardless.

Krige at Bonhams

HAVING UNEXPECTEDLY been granted a day off (two, actually) I was quite content popping over to New Bond Street yesterday just in the nick of time to see Bonhams’ South African Sale before they went up for auction today. Out of pure ignorance, I used to think South African art was all mediocre before slowly discovering its small but noteworthy patches of brilliance. Francois Krige is one of them. Of the three galleries at Bonhams devoted to the South African Sale (Part II, strictly speaking) one of them darkened with individual lights highlighting the particular pieces hanging on the walls. (more…)

The Arrival of Autumn

Here in London, after a long Indian summer, it has finally turned to autumn. One’s mind turns automatically to autumns past enjoyed, and I can’t help but think of that splendid season in the Western Cape. Of course, as the recent coverage of the royal visit to Australia reminds us, it’s not autumn at all in the Southern Hemisphere but rather warm and summery.

The other day, however, I stumbled across this photo on Flickr (more…)

The Major-General’s Statue

Die staanbeeld van Maj-Gen Lukin in die Kompanjiestuin

While Afrikaans is a mild obsession of mine, I do like finding those holdouts of what they used to call “High Dutch” — in contrast to the ordinary South African spoken Dutch which, because of its differences in grammar and spelling, was eventually recognised as the language Afrikaans.

One such old Dutch holdout can be found on the statue (Af: staanbeeld; lit.: ‘standing-picture’) of Maj. Gen. Sir Henry Timson Lukin in the Company’s Garden, Cape Town. The pedestal proclaims in a very handsome font the General’s rank, name, and orders. In Dutch: Majoor-Generaal Sir Henry Timson Lukin, KCB CMG DSO, Commandeur Legioen van Eer, Orde van de Nyl.

Most of this works perfectly well as Afrikaans but for two slight differences. First: The lack of ‘i’ in de always indicates Dutch rather than Afrikaans, but because of the relative youth of Afrikaans, de can sometimes be employed as an antiquating device. For example, when translating the name of Captain Haddock’s ship in the Afrikaans translation of the Tintin book, the translators chose De Eenhorn (the Unicorn) rather than Die Eenhorn. Obviously an old-fashioned sailing ship would belong to a Dutch-speaking era rather than an Afrikaans-speaking one.

Second is the military rank. Here translated as majoor-generaal, in both Dutch and Afrikaans this evolved into generaal-majoor. Just one of those things. The South African Defence Forces has a history of experimental military ranks which did not last: Commandant-General (for General), Combat General (for Major General), Colonel-Commandant (for Brigadier), Commandant (for Lieut. Colonel), and Field Cornet (for Lieutenant).

There’s your random bit of Afrikaans arcana for the day.

‘I Have Prussiandom in my Blood’

Loriot on Prussia and Prussianness

November 2003

November 2003The Viennese weekly Falter interviewed Vicco von Bülow — better known as Loriot — in November of 2003. In part of the dialogue, Loriot explored the Prussianness of his family and upbringing, musing upon some aspects of what it is to be Prussian, turning away from the simplistic categorisations. Via Günter Kaindlstorfer.

…

Loriot: I am committed to my Prussian roots. I was born a Prussian, I have Prussian, so to speak, in my blood. That this defines you for yourself is not new. One is born there, so one has to accept it.

Prussian vices have caused too much harm over the past 150 years.

Loriot: That’s right, I will not deny it at all. Nevertheless, I am proud of my native town of Brandenburg; I am also proud of my country of origin. Here I will not deny, however, that I have been occasionally affected by the disaster that this country has done throughout history, time and again. Only: Which country has, over the centuries, not caused many evils? I will not have the Prussian reduced only to its negative sides. (more…)

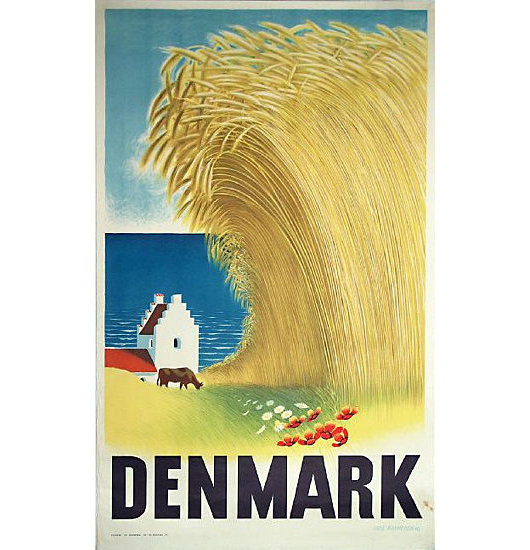

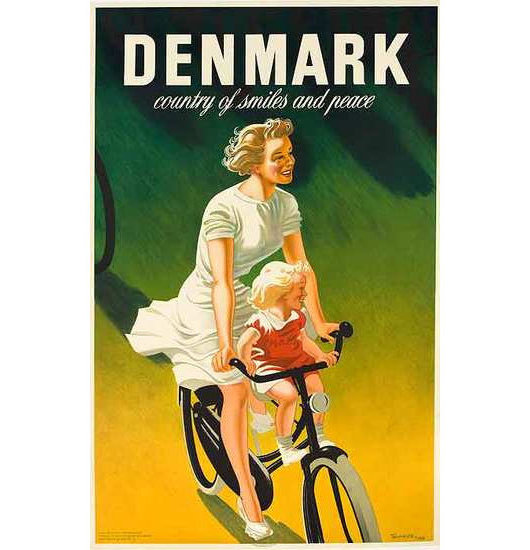

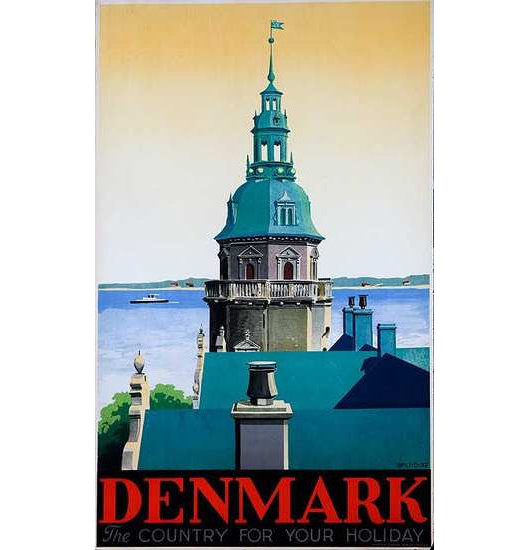

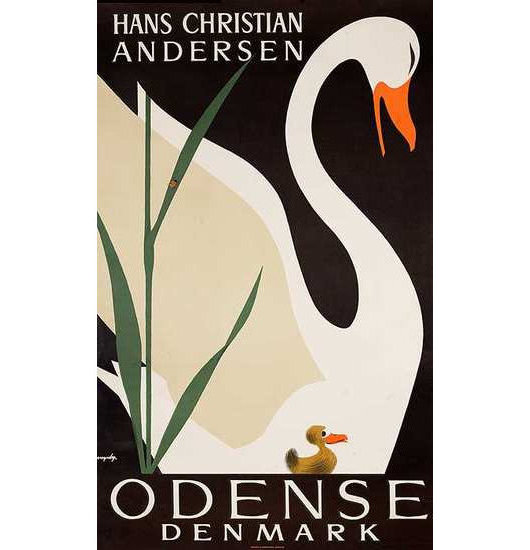

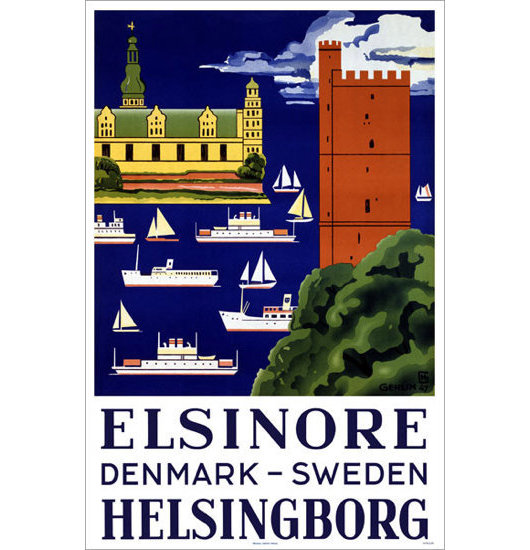

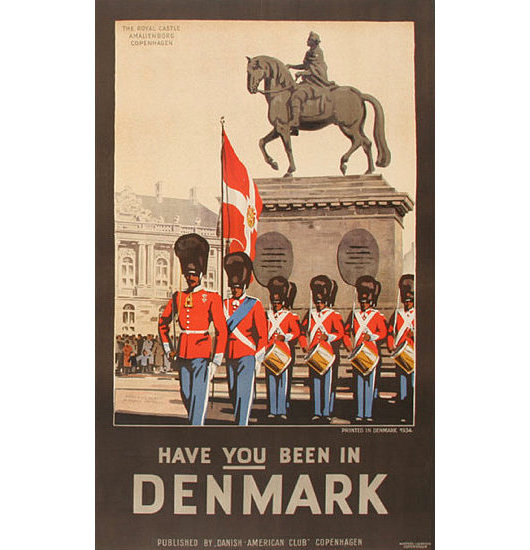

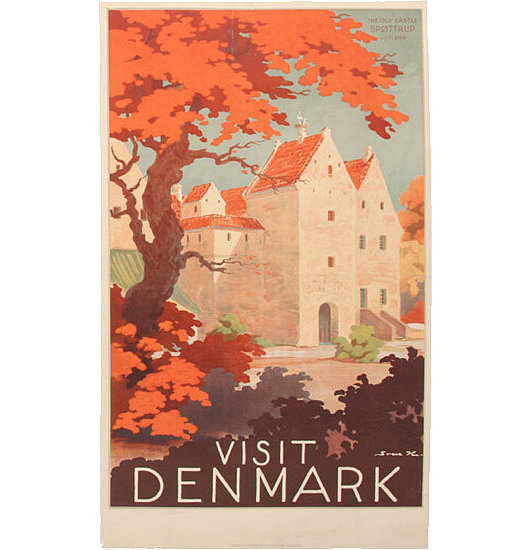

Visit Denmark

Having previously explored the world of Finnish travel posters, I happened to come across various posters advertising the happy kingdom of Denmark, whose current monarch is a Cambridge-trained classical archeologist, vestment designer, and published Tolkein illustrator. Click the little numbers to view the posters.

Previously: Come to Finland

Best Universities in the World

From north to south, a completely arbitrary and biased accounting

WHILE UNIVERSITY rankings within countries have been popular for some time now, especially in the United States and United Kingdom, it’s only been in the past decade or so that worldwide rankings of universities have come to the fore. The most widely known is probably the Academic Ranking of World Universities produced by Shanghai Jiaotong University, alongside the QS World University Rankings from the firm Quacquarelli Symonds, and the T.H.E. World University Rankings from the weekly magazine Times Higher Education. All such ratings employ varying statistical matrices and methods of divination obscure to the outsider but which, one supposes, must have some form of merit. They are more useful for gaining a general impression of the place of a university rather than comparing and contrasting two or more particular institutions.

The aforementioned ranking structures are rather to formal for us to gain all that much knowledge from. Personal interactions, reputation, age, style of architecture, and other such factors carry much greater import when I judge universities. Oxford and Cambridge, whether you like it or not, are still the top universities in the world, even if they might not be our favourites. You just can’t beat them. While they might not be as much fun as other places, they come closest to achieving the balance of age, tradition, interesting people, serious research, good location, and general niftiness.

For a certain type of person, Harvard remains paramount among American universities, but to be a Harvard undergrad has carried a certain social stigma in our quarters for the past two or three decades. Harvard Business School, however, remains perfectly acceptable. In the Ivy League, Yale, not Harvard, is king, followed by Brown (not thanks to its radical professoriate but rather due to the strong Continental infiltration amongst its studentry). Dartmouth is the fun #3 of the Ivies, while the rest are forgettable (well, Princeton’s not bad really — it has the Whitherspoon Institute — but Cornell, Columbia, and Penn are yawn-worthy).

Up to this point, we have been speaking generally, but there are topical institutions of course. If you really must study ‘business’, then there’s Harvard Business School or INSEAD. Are there any other business schools of actual note? In the military realm, Sandhurst is the unquestionable king. The École royale militaire in Brussels is up there — being Catholic, Francophone, and monarchic attracts good elements from outside Belgium. In the States, there is the Citadel and VMI, but not much else (the federal ‘service academies’ have poor reputations except for Annapolis). One doesn’t hear much about Saint-Cyr these days.

Speaking of France, the reason one can’t come up with proper rankings is because some institutions or groups of institutions would be entirely outside it. The grandes écoles are the best example. They are superbly elitist, the absolute top, but they mostly exist in that little French world, with all its delights and limitations.

But for ‘topical’ institutions, the University of London has plenty: SOAS, LSE, the Cortauld, the various institutes of the School of Advanced Study, etc., etc.

There are also those interesting little schools of art history and conservation, attached to museums like the V&A or auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s. The École du Louvre, however, must be the queen regnant of these schools.

Charles Taylor’s presence at McGill alone makes it worthy of note, but one suspects there are other strengths at the university. At any rate, it is still a perfectly respectable place to be an undergraduate. Boston College is also quite strong at the postgrad level, except in the theology school where heresy is widely believed to be thriving. Given the wealth and particularity of America’s universities, there are small and unknown centres of excellence in many unexpected places (for example the quite strong literary translation centre at the University of Rochester).

Rome’s universities of both church and state have shabby academic reputations but still attract for being Roman. One always hears seminarians complaining about the Gregorian, but no one can never really complain about Rome, and being a student or a seminarian is as good a reason to be in Rome as any. Rome also has John Cabot University, an ‘American’ institution divided between Americans on their semester abroad and the full-timers (often the layabout members of larger European families, who also frequent the American University of Paris).

And of course many of the Italian universities are not so much places of learning as conspiracies for the avoidance of unemployment on the part of their academics and administrators. Regrettably, much Italian talent moves abroad for higher salaries and better working conditions (Cavalli-Sforza, to name but one, at Stanford), but the handful of scuoli superiori (e.g. the Scuola Normale in Pisa) still maintain their dignity.

In Spain, Salamanca is well-regarded, and there are a number of newer, private, properly Catholic entities that have been created. Of course, Opus Dei are very proud for having created the University of Navarre ex nihilo. Portugal, meanwhile, has yet to recover from the Marques de Pombal’s disastrous eighteenth-century reform of Coimbra.

If you’re one of those people who actually wants a proper education then, for better or worse, you must go to America. Thomas Aquinas College in California and St. John’s College in Maryland might be the last genuine places of higher learning in the European world. Attempts are being made to found a British Catholic version, and many imitations (Catholic, Protestant, and secular) exist around the United States.

If I could name some other honorable mentions in addition to those featured below, I would add Dublin (Trinity, that is), Bristol, the Collège d’Europe, Leiden, Leuven, Utrecht, Uppsala (and all the old Scandos), Heidelberg (and a dozen other German universities), King’s Halifax, Trinity College in Toronto, some parts of Berkeley, York for graduate study but not undergrad, the C.E.U. in Budapest (despite being a Soros project), and Exeter and Warwick aren’t bad really. Some universities, like the Jagiellonian in Kraków or the Charles in Prague, must be mentioned due to age, but I have to plead ignorance as to any knowledge of their current state.

I’m probably leaving out a dozen places that deserve a mention but I’ve forgotten; such are the limits of our fallen human nature. Here follows, arranged from northernmost to southernmost, our completely arbitrary and biased accounting of the six best universities in the world. (more…)

Gregor von Rezzori

THE BOOKS OF Gregor von Rezzori, according to the introduction to this interview (found via Three Percent), depict “a world now almost wholly disappeared—Central Europe in the years between the two world wars—through the memories, ruminations, and loves of their narrators, men who have survived into the postwar new Europe but who can never fully detach themselves from that lost world. It is Gregor von Rezzori’s world, too. An Austro-Italian nobleman born in the Bukovina region of Rumania in 1914, von Rezzori was raised there and in Vienna. He lived in Germany during and immediately after the Second World War, and he currently divides his time between Tuscany and New York.”

Bruce Wolmer I’m tempted to begin by asking the question interviewers on French TV like to pose: “Gregor von Rezzori, qui êtes-vous?”—Who are you? Which is immediately funny considering that the enigmas and paradoxes—and humor—of identity is a central concern of your work. But one wouldn’t know that reading the reviews, where you’re almost inevitably conflated with the first-person narrator.

Gregor von Rezzori Absolutely. This is such an old discussion: To what extent are books autobiographic? It’s ridiculous. As Flaubert famously said, Mme. Bovary c’est moi. You can’t eliminate yourself totally unless you’re Shakespeare.

BW That goes against the grain of much contemporary opinion and practice, which claims to be getting down to the truth of the author rather than the truth of the fiction.

GvR The Death of My Brother Abel is narrated by a writer. The narrator, the “I”—and funnily enough he is less my own person than any other first person in any of my other books—the narrator in The Death of My Brother Abel is a totally fictitious character. But, of course, nowadays people have little curiosity about examining such complexities. There is this desire of authenticity and transparency which connects with the curious contemporary belief that everybody is, or should be, an artist.

I must tell you that when I was young I never had the faintest idea that I should ever become a writer. I studied mining engineering, of all things. I came to writing by accident at a rather ripe age. I never thought of really having the urge to express myself, but obviously I had it in some way or other. But without ever having heard the phrase, I had to find my identity. That’s one of those dreadful verbal expressions. A phrase like that becomes fashionable and then becomes a slogan and becomes really a program for people’s lives. Every young man or girl nowadays ponders about his or her identity without even realizing what it is. My identity is “I”. It takes a long time to learn that that much celebrated “I” is never lost, but never really found either.

Anyway, in my case I was having a period in my life in which I didn’t have anything else to do—this was before the war—so one day I sat down and wrote a story. Somebody got hold of it and sent it to a publisher. They instantly wanted me to write another one, which I did. Because I thought, my God, this is a very agreeable way of earning money. How wrong I was I found out later. But by then it was too late.

BW A disagreeable way of not earning much money.

GvR Yes, yes. Somebody with a little bit more intelligence doing the same amount of work, you’ll become an Onassis. Well, who needs that? But it’s in real disproportion. Then when I realized what crap I had been writing, you see, I sat down, and just then the war came. I was fortunate—I didn’t actually have to be a soldier exactly. I was born in Bukovina, Rumania. Before Rumania went into the war it was given to the Russians so I was already more or less a Russian although I still had a Rumanian passport and was living in Vienna at that time. When Bohemia was taken by the Russians I went to our ambassador in Berlin, who was a friend of the family, and I said, “What shall I do, what am I supposed to do?” He said, “Well, you are supposed to go home and find a new identity because you don’t exist. And then you’ll die from Mr. Hitler because within a short time you shall have to join in those struggles. I can’t prolong your passport. How long is it still valid?” I said. “For a year.” He said, “Keep quiet.” Which I did. It lasted for three more years during the war. I had my share of bombing and all that, but in the meantime I had the opportunity to really fill the unbelievable gaps in my knowledge by reading. I must tell you that I read very slowly and I need months to finish a real masterpiece, for example one of Broch’s novels.

BW I too read very slowly, and The Death of My Brother Abel took me a couple of months, which was fine, but it was interesting to see in the reviews how impatient everybody is: “Well, yes, there are wonderful bits here, but we shouldn’t be required to sit and…”

GvR Yes, the chutzpah to offer you 600 pages!

BW If one were to race through it, though, to read for information, one would lose a sense of the sheer intensity of the language. There are sentences in The Death of My Brother Abel so beautiful that they quite literally stopped me for five or ten minutes.

GvR What makes for the beauty of Proust, say, is that each page is a picture in itself. But it seems that to get people to read a thick book you need to offer them a juicy subject. Look at Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities. People are buying it, people are reading it like mad. For the so-called information, I suppose. A dreadful book.

BW When did you begin to think of yourself seriously as a writer?

GvR In Germany, right after the war, something absolutely absurd happened. You see, I sat down and for the first time I really wrote aggressively and got rid of all my hatred against a particular kind of German. I wrote a book—it wasn’t published until 1954—which the publisher rather ludicrously decided to call Oedipus siegt bei Stalingrad —”Oedipus Triumphs at Stalingrad.” But while I was writing that I was also working for the British-controlled radio in Berlin. One day there was a gap in the program and they said, “You are always telling us your silly stories, Jewish jokes, and God knows what all, now go and tell them on the microphone.” Well, there’s nothing more unbearable than somebody who tells one joke after the other. So I combined them into an invented country, which I called Maghrebinia. To make a long story short, the broadcast became a roaring success and the stories from Maghrebinia came out before the novel. With the consequence that, you know how Germans are, from that moment on I was The Maghrebinian. Tell any cafè waiter in Berlin or Frankfurt that you are a friend of mine and you will be superbly served.

BW Tales from Maghrebinia were lighthearted, popular stories?

GvR Of course. It was a success mainly because it was the first book after the war that you could laugh at. And it was hilarious and rude and whatnot, sort of Rabelaisian. It was also the first book after the war in which, with all the collective guilt then being felt in Germany, you could read a Jewish joke. As I say, it became a great success. I never got rid of that, whatever I wrote afterwards. It was read in the wrong key, so to say; people were always expecting me to be satirical and to make jokes.

BW Why wasn’t Oedipus siegt bei Stalingrad ever translated into English?

GvR It can’t really be translated, because it’s written in sort of German slang as if Ernst Junger were a drunken Prussian officer telling a story in a bar. It’s about German snobbism, about somebody who comes to Berlin in ‘38 in order to conquer the world, a sort of Berlin Rastignac. It pokes fun in a most atrocious way. The next book I wrote after this was a long novel, which has been translated into English as The Hussar. And then came An Idiot’s Guide Through German Society, which also began as a series on the radio. This offended many people because I had my finger in a burning wound. I claimed that in spite of everything that had happened since 1918 in Germany, the social structure had not altered, you still had an aristocracy with enormous prestige and wealth. And I poked fun at all that. But I’m not at all interested in what happens in Germany any longer. My books don’t sell there and my work is not taken seriously.

BW Abel took a very long time to write, yes?

GvR Indeed. More than 15 years. I disappeared for a while, so to say.

BW During that 15 year period while you were working on Abel you went to Italy?

GvR Yes, I was already in Italy. I am in Italy 35 years now.

BW The Death of My Brother Abel is an extremely ambitious book. There are very few contemporary books that have such a level of ambition—in literary terms, intellectually, historically, and even spiritually.

GvR Lady Annan called her piece about it in The New York Review of Books, “Transcendental Chutzpah.” Well I mean, see, it’s a book for writers. It’s not a book for readers. I like to joke that it should be read in creative writing classes. It is not for the normal reader. It took me 15 years to do and was my own attempt to understand what I was doing as a writer.

BW One of the issues explored in The Death of My Brother Abel is the death of Europe. Europe as a culture, as a way of life. That death has been, at least partially, to the benefit of America. You have that extraordinary, almost hallucinatory, passage in which your character Jacob G. Brodny, born in Central Europe but now a fabulously successful American literary agent and wheeler-dealer, is seen to wolf down the masterworks of European culture as if they were patè.

GvR My aggressiveness is not directed against America and Americans, it’s against Americanism, which is mainly a European phenomenon. Brodny is not genuinely an American. He’s an immigrant who came over here. He behaves more American than any other American, which you can see. And personally, if you ask me, I love and admire America. European culture has not been killed by America. It perhaps committed suicide during the First World War. And this is a thing which I also want very much to emphasize in the next volume of mine, which will be called Cain.

BW The idea of a culture committing suicide is right beneath the surface of Memoirs of an Anti-Semite, as well. Reading it, one becomes aware that the killing of the Jews in Europe, the Holocaust, was not only murder, but the suicide of a world, because for all the antagonism and dislike between the aristocratic and the Jewish characters, they existed in some necessary relationship, some vexed sympathy. They both shared a world that has now vanished. Perhaps it was just that that world vanished, but Jews lost something rich and irreplaceable as well. The moral difference being, of course, that nobody gave the Jews a choice in the matter.

GvR You see, first of all, I do believe that the aristocracy as a class never hated the Jews. On the contrary, the Jews were an object of jokes or disdain, in fact, but many other groups were much more so. As for the peasants and the Jews, it’s a somewhat different story. Whatever a peasant produces is by his hands and due to rot away. He slaughters the pig, but he can’t keep it for any more than a week or so. The Jews, on the contrary, had something that increased its value with time: money. That’s why it was easy for the peasants to believe that the Jews were the evil, exploiting ones.

BW Elie Wiesel has described Abel as an elegy, “the story of Europe seen through the eyes of despair.” How would you describe what has been lost from that world?

GvR Ah ha! Let me answer this exactly. What’s been lost is a particular light, a particular quality of air. And pity—the loss of pity is perhaps our greatest loss.

Now we have a completely different feeling for time, for instance. Time itself has changed. This is due to a blind belief in science. The simple fact is that European life nowadays, just like American life, is determined by money, led by money, as let us say a European would have been led by religion in the 14th century. In every aspect of life, money shows the way. It’s not that this loss happened from one day to the next; as a matter of fact, it’s a loss that started with the French Revolution, at least. Well, all this is rather vague. I shall have to find more metaphors for it.

BW Saying this flies right in the face of the optimistic consensus pervading modernity, the belief that most historical change, most technical and social innovations have been, on balance, for the better. You, or at least the narrators of your books, seem on the contrary to regret them.

GvR You see, I’m profoundly distressed, call it skeptical, and I don’t think I’m alone in becoming aware that we’re in a rotten place. We’re a rotten people; our culture is rotten. Deeply rotten. And to me the proof is that whenever we come in contact with another people, they are destroyed. A friend of mine who’s really one of the last really honest dealers in African art told me that he came to tribes which had never before seen a white man. The simple fact is that they look at him, and that he has a knife or lighter or something—it’s already a deadly encounter. You see, it’s lethal for them already. Similarly, I recently came back from China. The Chinese of my time were pig-tailed and Chinese, but nowadays they are exactly like myself, just a little bit more ethnic. It’s not really to their best interest. What I felt there now was that they have gotten rid of political fantasies and are fortunate enough to have had a religion, an early religion, sort of a black beaten-down art, so they can cope with such a loss in a rational way.

BW In your books there are passing references to the futility of revolution and of politics more generally. Were you affected, as were so many of your generation in Europe, by utopian hopes?

GvR Yes, of course, as a young man. Of course. I couldn’t very well escape from this. In the atmosphere of the ‘30s we all believed, even without an articulate ideology. We all believed in a new world that was about to come. The promised technology. Utopia. Look at the paintings of Kupka at that time. You saw Metropolis everywhere. And Metropolis is not thinkable unless a new man and a new woman are created, a new mankind. In the ‘20s and ‘30s we were unbelievable optimists, you see, who were then bitterly disappointed. But my skepticism, my pessimism, is not just the result of political failure. It goes much deeper. Much deeper. And I haven’t found an answer. I mean whenever I think of it, of what’s been lost, it certainly hasn’t been lost by the Americanization of Europe. What I call Americanization would have happened even without America. The greed for money, the power of technocracy and misunderstood science and so on, all that would have happened even without the example of America. What has been lost is pity and the capacity to dream. You Americans still have the capacity to dream even if you are also sleepwalking in a merry way. But we can’t any longer. We’re awake. Too much awake. Europe is silent and exists now in an abstract way, totally according to abstract rules. For instance, when I say we’ve lost pity, you can see just one small example of it in, say, the demonstrations for the victims of Mr. Pinochet or whoever. But you wouldn’t find those vociferous protesters caring about the beggar on the street. That direct relationship between human beings is getting lost due to abstract ideas about humanity.

BW Ideology.

GvR Yes. Ideology. Political ideology.

BW Which, of course, is a major theme of The Death of My Brother Abel: the increasing abstraction of life, the emptying out of experience.

GvR Exactly.

BW Which leads to the question, Pilate’s question, your books pose so often: What is truth?

GvR What is reality?

BW What is reality and what is fiction and what are the transformations and negotiations between them? You plainly dislike the society of information, the society of media, where people think they’re getting reality from newspapers, television, and magazines. Instead, you’ve said that Anna Karenina — now there’s reality!

GvR Do you remember in Abel there is a long, long, perhaps much too long passage on the narrator’s having an affair with a girl who lives in one of those postwar high-rises. He visits her and thinks about the fictitious reality forced on us by the media and how you lose your identity because you don’t know who you are to cope with all these things which are much beyond your reach, beyond your personal sphere. I mean everything in our time is done, is given, to lose your identity. Then, of course, you have to go look for it, to put it primitively.

BW In terms of your own writing, how does that govern your aesthetic? Not to put too fine a point on it: Why do you write?

GvR Yes, yes, yes. Why do I write? “What sin to me unknown/Dipped in ink, my parents or my own?” Listen, I suppose that in fact writing, whether you know it or not, is the attempt to find an identity. Knowing the secret of the “I” that never can be lost in spite of all the changes it undergoes throughout a lifetime, there you have already the secret theme of every fiction writer, don’t you think so?

BW The search for the voice?

GvR The search for the voice. Also the search for the secret of transformation, of living many lives in one life. The possibility of what I do, of writing hypothetical autobiographies endlessly. And, I mean, Anna Karenina is a reality in so far as it is the most dense invention of fiction, the most concrete.

BW You frequently allude to Nabokov’s saying that when we speak of reality we must put it in question marks.

GvR In quotation marks. Which, of course, are also question marks here.

BW What has been Nabokov’s influence on you?

GvR Well, there were many other influences first. I didn’t read Nabokov until late. But when I had started to write Abel in its first version, I got Nabokov’s Pale Fire in my hand and instantly put my pen down because I found that there was the book I wanted to write already in the best possible form. Then I collaborated on the translation of Lolita into German, and I became aware that I shall never achieve the almost medieval craft of Nabokov’s to link fiction with literary allusion and write a book on many layers—of which one is a direct and fictitiously concrete reality, and behind there is the other reality, the literary reality of all the allusions, all the relations of literature with other literature. At the same time that it’s discouraging, it’s very challenging.

BW Other influences?

GvR Everything influences you as a writer, whatever you read. I believe there isn’t any such thing as a bad book, because you take out of any book something by which you learn, even if you throw it away. Then there are writers who encourage me immensely and writers whom I admire so much that I put down my pen and say, “I can’t write.” For instance, I can’t read ten lines of Robert Musil and keep on writing, I stop for a week at least. Even Joyce. He discourages me totally. But then there are others who encourage me. Thomas Mann with his sort of schoolboyish sense of humor challenges me to get a little subtler. Ironic. And so on.

BW Cèline?

GvR Well, yes. Not consciously, but the violence. In literature, particularly at that period, a certain barbarism is necessary. Also for the sake of honesty. You can’t be suave and God knows what in a time like ours. Also there is in him an urge for iconoclastic action which was also very much an aspect of German Expressionism after the First World War.

BW Your narrator says he seeks to write in “a style of barbaric haul gout.” There is anger and disgust beneath the suavity and jaunty, nonchalant elegance of your prose.

GvR I’ve become aware that I can only write well out of either love or hatred. Direct feeling. I need that. When I love it becomes, because I am sentimental to the core, it becomes too sweetish. It’s like playing on the cello. The best things are wrought in hatred. The more the world around myself gets nostalgic, the more furious I become with nostalgic feelings. I know there’s something I deeply mistrust in that. In fashion, in modes of living, people are trying to revive bits of history, the ‘20s and ‘30s particularly, that they don’t understand. Take the German painter Anselm Kiefer, who’s accused by some Germans of being nostalgic for Nazi times, which is absurd. But if he is, he’s doing the same thing as everybody else does. Without realizing that they are nostalgic for the ‘20s and ‘30s they are nostalgic for what formed fascism.

BW Kiefer’s watercolor Winter Landscape was used for the book jacket of The Death of My Brother Abel.

GvR Yes. Kiefer also denounces in sorrow and in anger. I like him very much.

BW In Abel, you talk about the relation between individual literary style and the zeitgeist, that it is not we who write, but the times which write us, so to speak, which demand a style of us.

GvR Whatever we do is not only led by our individual fullness but by trends in the zeitgeist, by things that are far out of the reach of our control. We don’t know what happens to us. I mean the simple proof is that if you take a German newspaper of, say, 1934 and read an article written by Dr. Goebbels, you wouldn’t believe your eyes. The crap he has said. And—I know, I lived through it—people read it as if it were the Bible. Intelligent people, but totally blinded at the time. Or, another example I use, people from a particular epoch all have a more or less similar handwriting. You can recognize it as 18th century, or whatever, at first sight. It means that something happens to us which we don’t even realize, in ideas as well as in our way of perceiving the world. For example, the break between Romanesque and Gothic art or, in our own time, the sudden break into abstract art, you can’t tell me that it’s a logical evolution. That is rationalizing it as historians always do—backwards.

BW You’re not saying, however, that individual style doesn’t exist?

GvR It certainly exists. There are artists who are not great in the sense of a new creation but just because they represent in the utmost possible form the style of their period. Somebody like Seurat, for instance, is not a great genius in painting, but still such artists represent their period and the spirit of their period in the purest form. But nothing more, nothing personal.

BW Which would make them inferior to an artist who’s able to…

GvR Picasso certainly is not in that line. He’s overwhelmingly personal and individual. Those others aren’t.

BW And in terms of your own work, you would aspire to…

GvR Oh my God! It sounds silly, but I am so astonished that I can write a phrase at all that I wouldn’t know, I don’t reflect that much. I don’t put myself in any rank or school or anything of that kind. I believe that I’m rather personal, but as for representing a particular zeitgeist…I may. I’d be very proud if I did. On the other hand, I have written in Abel many times that the tremendous fear of any writer or artist who believes that he has some idea, something to say, is that they know perfectly well that at the same time, the very same time, hundreds of others have already either said it or are about to say it or there’s another chap who says it much better and liquidates you totally.

BW You have been widely criticized for having your narrator in Abel say that the postwar Nuremberg trials were a sham. As you yourself covered the trials for the Hamburg radio, I assume that you feel similarly.

GvR Let us put that straight. First of all. I do not believe that the Nuremberg trials were a complete sham. They were a failure and therefore a great delusion. This was not due to, say, moral failing or any manipulations behind the scenes, it was due to my great enemy, stupidity, overwhelming collective stupidity. Or the impossibility, even on the part of intelligent people, to cope with things established by stupidity. For instance, you know there has been endless discussion about the legal basis of the trials. And I hope that I have the opportunity to expand this a little bit more explicitly in Cain, the book I’m planning to follow Abel. This has something to do with zeitgeist, if you want to put it that way. I think that all the great moral energy which was necessary to fight the Nazis—when finally victory was achieved there was a moment of total exhaustion. And nobody any longer seriously believed in what had encouraged millions to fight the Nazis and even to die. I mean many wars have been undertaken for a certain or just cause but never more so than in the struggle against fascism and Hitler. The trouble was that also you became aware that it wasn’t stamped out, just pulverized. My feeling is that instead of having one wicked Satanic dictator or a group of wicked people—the Nuremberg defendants, many of them—who demoralized a whole nation, nowadays it’s pulverized and each of us carries within himself a little bit of that venom, instead of 18 millions Nazis, nowadays there are in this world 500 million Nazis, if not more.

BW The trials, then, were false because they suggested that evil could be juridically exorcised and the world put right again?

GvR It’s like that famous statue of the chaps planting the American flag after the Battle of Iwo Jima. The good cause was fought for and won, and now we’re going to make a law that will eliminate the possibility of having the horrors repeated forever. That was too much. Too high.

BW You say that your greatest enemy is stupidity?

GvR Not mine only. You can claim that a man is born good and not wicked, but certainly not that all men are born intelligent. There’s a question also of quantity. Put ten people together and the quota of intelligence is brought down to almost zero. And if you put one hundred thousand together, well, it’s all over then. Plant a great idea, a magnificent invention, or a great example into the mass of mankind and it becomes what Jesus Christ became—the Catholic Church. Endless chains of misinterpretations and misunderstandings—that’s what I call stupidity. A really stupid and dull person can be as amiable as anybody else—charming, but not intelligent. The accumulating and progressive stupidity of mankind is something I fear. And it can’t be fought.

BW And it’s much more pronounced in mass societies.

GvR Of course. The very moment you form a mass out of a certain number of people, it necessarily becomes a body of stupidity.

BW What values enable you to keep on, to continue writing and living with evident grace and vivacity of spirit, in spite of such profound pessimism.

GvR You see it’s the secret of the “I”. In spite of all the strange morphologies and transformations of myself during my lifetime, the “I” is something unchanged, something I can’t explain, not even to myself, and it has its destiny. I believe in that. I may be very capable of suicide, certainly, but I believe that the hour has to come for it. The hour has to come for my dying, anyway. As long as there is life, I shall try to cope with the outer world.

BW And other people?

GvR Certainly. The strange thing is that I despise the mass but I love other people. It’s paradoxical, but I really do. I feel friendly towards everybody I meet. Basically. But in the whole I despise them.

BW One last question. You’ve said, “I’m an aesthetic absolutist and an ethical nihilist.” Can you elaborate?

GvR (laughter) Ah, but what is there to add to that?

Canada’s Royal Standards

In anticipation of the recent visit of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge to Canada, the government of that dominion unveiled new Canadian personal flags for the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Cambridge. The British Empire started out as a group of states and colonies united in the British crown, but as the Empire evolved into the Commonwealth, dominions were gradually recognised as sovereign entities of their own. Thus when, for example, Elizabeth II visits, say, Vancouver, it is not the ‘Queen of England’ who is visiting but the Queen of Canada exercising her functions in her own country. (This is a point frequently lost upon ideological republicans). Even when Elizabeth remains in London she puts on different ‘hats’ for different occasions. The only time I ever saw the Queen was at a Service for Australia at Westminster Abbey, thus it was the Queen’s Personal Flag for Australia which flew from the tower of the Abbey, not the British Royal Standard.

The Queen’s Personal Flag for Canada (above, top), often informally known as the Canadian Royal Standard, was devised in 1962 (the same year similar banners were created for Australia and New Zealand). Until 2011, the Queen was the only member of the Canadian Royal Family to have a personal flag for Canada, but now she is joined by her son and grandson, the Prince of Wales and the Duke of Cambridge respectively.

Reviving Manhattan’s Parisian Splendour

The new Ralph Lauren building at Madison & 72nd

“PRACTICALLY PERFECT in every way” was how the nanny Mary Poppins described herself in the Disney film, but fashion designer Ralph Lauren has given birth to an architectural grande dame on the Upper East Side that might justifiably make a similar claim. In this age of fashionable-today-dated-tomorrow starchitecture, the Bronx native has swum against the current and delivered for the people of New York a most welcome piece of architecture with his new store on the corner of Madison Avenue and 72nd Street.

Those familiar with the neighbourhood might be a bit confused: doesn’t Ralph Lauren already have a beautiful French chateau on that street corner? Worry not, the old Rhinelander mansion has not been demolished. Rather, its interior was recently given a ‘masculine makeover’ so shoppers can peruse and purchase any of Ralph Lauren’s men’s lines there.

Across the street, meanwhile, with his new women’s store, Ralph Lauren has reinvigorated Manhattan’s faded glory with a new injection of Parisian splendour. The unremarkable “taxpayer” two-storey on the site was razed and a completely new four-storey structure has risen in its place. Two smaller wings flank the middle, which is recessed above the ground floor’s triumvirate of skilfully curved arches. The two central storeys above are topped by a more reserved attic, with the facade clad in American-sourced limestone throughout. (more…)

Winchester Mansions

STARING ACROSS Sea Point Promenade towards the waters of the Atlantic in Cape Town, there sits Winchester Mansions. The hotel was built in 1922 in a style emblematic of the period’s revival of interest in the Dutch colonial age at the Cape. People often associate the 1920s with Art Deco, but the style was only just emerging in Paris at the time, and wasn’t even called ‘Art Deco’ until the 1960s. The ‘mother city’ has its fair share of Art-Deco and Moderne buildings, but architectural trends took a while to arrive in South Africa — though they tended to last longer then elsewhere. The Cape Dutch Revival emerged in the 1890s and perhaps reached its high-water mark in the 1900s and 1910s. Curiously, it is not associated with the simultaneous emergence of Afrikaans as a language and the rising consciousness of Afrikaner identity, but rather with a very Anglo and colonialist mindset. It was Dorothea Fairbridge and Milner’s ‘Kindergarten’ — respectively the social and political forces seeking to unite all of South Africa under the British crown — that promoted the adoption of the Cape Dutch as a national style. Thus the years leading up to Union in 1910 and its initial decade or two were the heyday of the Cape Dutch Revival as it was the favoured boustyl for the respectable Cape- and Rand-based imperialists.

Mamarazza

The photographs of “Manni” Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn

IT’S A CRACKING photo; the sort of thing guaranteed to irk the puritanical and bring a smile to the good-humoured. The thirteen-year-old Yvonne Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn takes a swig from a bottle while her brother Alexander, just twelve, sits with a half-smoked cigarette. Taken aboard the yacht of Bartholomé March off Majorca in 1955, the photographer was Marianne “Manni” Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn — the mother of Yvonne and Alexander — who’s known by her photographic soubriquet of “Mamarazza”. (more…)

Old Master Paintings at Sotheby’s

A Florentine Artist, The Madonna & Child Enthroned Flanked by Saints Bridget & Michael

1450; Tempera on panel, 72 in. x 85 in.

QUITE A FEW interesting pieces up for auction today as part of Old Master Week at Sotheby’s in New York. The above altarpiece has been attributed to various artists. For much of its life was called the Poggibonsi Triptych, but scholars now believe it to be the work of the Master of Pratovecchio. This attribution was supported by no less an authority than Roberto Longhi, who (as the catalogue notes point out) “considered him an artist of note who contributed to the Florentine transition from the early fifteenth-century serenity and intimacy of Fra Angelico and Filippo Lippi to the more dynamic forms found later in the century.”

The altarpiece, commissioned from a certain Giovanni di Francesco in 1439, was acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum in California, which is now auctioning to raise funds for future acquisitions. (more…)

The City of Unexpected Charm

One of the things I like about Cape Town is its continual ability to surprise by throwing up surprisingly handsome buildings in unexpected places. To be honest, there is a great deal of mediocre architecture in the city, though I’d argue Cape Town’s mediocre architecture is better and more humane than, say, New York’s or London’s. But if you keep your eyes open to the world around you as you potter about the Cape, you can stumble across some happy little structures. This little building in Rondebosch is one such example. It sits on Rouwkoop Road, the street which takes its name from the old house that is no more. The N.G. Kerk Rondebosch is just down St Andrews Road one way, and St. Michael’s Catholic Church is just down Rouwkoop Road the other way. (more…)

Hail, Queen Europe!

The very name of Europe is feminine: Europa, the Phoenician princess of Greek lore, abducted by Zeus. From Strange Maps, we find this cartographic representation of Europe as a queen: Spain the crown, Germany the hearty bosom, Italy the graceful arm, and Sicily the Orb of Europe. The map was produced by Sebastian Munster in Basel in 1570 and was recently up for sale from Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps.

“During the late sixteenth century,” the map gallery writes, “a few map makers created these now highly prized map images, wherein countries and continents were given human or animal forms. Among the earliest examples is this map of Europa by Munster, which appeared in Munster’s Cosmography.”

South Africa in the New Year’s Honours

One CMG and three MBEs show links between Britain and South Africa

Despite breaking its constitutional links with the Crown over fifty years ago (c.f. here), South Africa continues to enjoy close social, economic, and cultural ties with Great Britain, a fact borne out in the recent New Year’s Honours list. Of the numerous individuals awarded for their public service, four from this year’s list show the relationship between these two countries. Most prominent is Fleur Olive Lourens de Villiers (above), who has been named a Companion of the Most Distinguished Order of St. Michael and St. George. Ms. de Villiers, a graduate of Pretoria & Harvard, is Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies. From 1960 onwards, she has been a theatre critic, economics correspondent, leader writer, columnist, political correspondent, newspaper editor, and travelling correspondent around the world, in addition to working with the De Beers Group and Anglo-American. She was one of the four contributors to the Institute of Economic Affairs’ 1986 study Apartheid: Capitalism or Socialism? which examined the role of the state and its race policy in the South African economy. (more…)

The Start of Something Big in Argentina

The first-ever Nuestra Señora de Cristiandad Pilgrimage to Luján

SMALL SEEDS, IF well-planted and tended to, flower into much larger growths. On a Friday morning last month, just four pilgrims set out from the town of Rawson in the Buenos Aires province of Argentina, but by the time they reached their destination — a Latin Mass in the Marian basilica of Luján — their numbers swelled to nearly a hundred. The pilgrimage of November 5th, 6th, and 7th, under the patronage of ‘Our Lady of Christendom’ (Nuestra Señora de Cristiandad) was inspired by the traditional Paris-Chartres pilgrimage every Pentecost weekend. The organisers hope that, like the Chartres pilgrimage, this trek to Luján will become an annual recurring event.

“Renewing Christendom in Argentina” was the theme of this year’s pilgrimage, which “seeks to promote the rich tradition of the Roman Catholic Church for our times” the organisers announced in a press release after its completion.

“This new 100-kilometre pilgrimage was an act of reparation and praise to God, imploring the salvation of souls through the renewal of Christian culture and the rediscovering of the bi-millennial tradition of the Church.” (more…)

Napier in the Overberg

NESTLED IN the Overberg, the little town of Napier owes its existence to a dispute between two neighbours. In the earlier part of the nineteenth century, as the little farm villages of the Cape became more firmly settled, the Dutch Reformed synod had to choose which towns were deserving of their own church. In 1833, the congregation in Swellendam decided to build a church further south to meet the needs of its members there, but couldn’t decide between two locations. Michiel van Breda wanted the church sited on his farm, Langefontein, while Pieter Voltelyn van der Byl wanted it built on his property, Klipdrift. Neither van Breda nor van der Byl would give way, so churches were built in both places, the town of Bredasdorp growing around van Breda’s church and the town of Napier founded around van der Byl’s church. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories