Featured

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Palace of Holyroodhouse

HOLYROOD IS SUCH a pleasant spot, despite the recent intrusion of an ostentatiously ugly government building designed by a Spanish architect. The other day, while visiting Edinburgh, I heeded the recommendation of the Prettiest Schoolteacher in Clackmannanshire to sample the burger at the Holyrood 9a. It was quite delicious, though not perfect, and was splendidly washed with a pint of Kozel (most un-Caledonian, I concede, but you can get Deuchars in London, you know).

Afterwards, our little party decided to have a little wander down Holyrood Road towards the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the epicentre of the Scottish monarchy.

Nestled between Calton Hill and Salisbury Crags, the Palace sits at the end of the Royal Mile that runs between it and Edinburgh Castle. With the Old Town to its west, the expanse of Holyrood Park flows off to the south and east of it. (more…)

Palacio Legislativo Federal

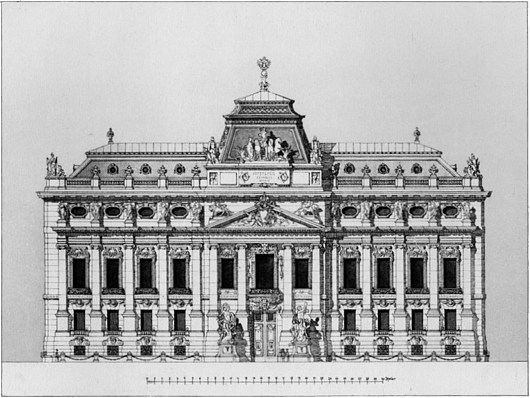

MOST OF THE major American countries have large parliamentary buildings built at the height of their prosperity in the decade before and after 1900, but Mexico is a particular exception. (Brazil, for complicated reasons, is another). In the 1890s, the government of President Porfirio Díaz decided that it needed a grand legislative palace whose magnificence would be worthy of the head of state’s own grand appearance. A competition was held and an entry chosen as the winner, but the victor was disregarded in favour of a new design by a French architect.

Émile Bénard had assisted the great Charles Garnier in draught work for the celebrated Paris Opera House which now bears that architect’s name. In the 1890s, Bénard became famous for winning Phoebe Hearst’s architectural competition for the campus of the University of California at Berkeley with his entry “Roma”. The Spectator wrote from the London of the day, “On the face of it this is a grand scheme, reminding one of those famous competitions in Italy in which Brunelleschi and Michelangelo took part. The conception does honor to the nascent citizenship of the Pacific states.” Unfortunately, very little of Bénard’s scheme for the academic complex was completed.

Fit for a Duke in Covent Garden

Russell House, No. 43, King Street

This apartment occupies the piano nobile of a 1716 house designed by Thomas Archer for the Earl of Orford, then First Lord of the Admiralty. He obtained the lease for the site from his uncle, the Duke of Bedford, on condition he tear down the house located there and build a new one. Batty Langley, the eighteenth-century garden designer and prolific commentator hated it, and devoted over 200 words of his Grub Street Journal (26 September 1734) to slagging it off. The Grade II*-listed building looks onto Covent Garden Piazza and has seen a number of uses over the years. (more…)

An Otto Wagner Embassy

The unbuilt Imperial Russian Embassy in Vienna

Otto Wagner was an exceptionally talented architect, though not, I think, the genius that many people would credit him with being. In the most emblematic work for which he is known, the Kirche am Steinhof in Vienna, there is too much angularity and not enough flow, curvature. For a free-standing structure it feels a bit stultified and uptight despite the brilliance of the individual elements of the design. I much prefer his Post Office Savings Bank and Stadtbahn stations.

Stumbling through the archives the other day, I came across this unexecuted Otto Wagner design for an Imperial Russian Embassy in Vienna: one now-vanished emperor’s embassy to another. From earlier in his career, it’s not as distinctively Ottowagnerian, but I admire the composition of the façade. The bulbous curved projections into the courtyard, however, are unfortunate, and too large for the space. (more…)

The Impetuosity of Youth

From the Flickr feed of South Africa’s Etienne du Plessis:

These pictures were taken 2 October 1964: I was the pilot [writes Quentin Mouton]. The pictures are original and not ‘touched up’. The ‘Pongos’ (Army types) were on a route march from Langebaan by the sea to Saldanha. The previous night in the pub one of them had said: “Julle dink julle kan laag vlieg maar julle sal my nooit laat lê nie!” (You think you can fly low, but you will never make me hit the deck). Hullo!!!

I went to look for them on the beach in the morning and was alone for the one picture. I was pulling up to avoid them. In the afternoon I had a formation with me and you can see the other a/c behind me. (piloted by van Zyl, Kempen, and Perold).

A friend by the name of Leon Schnetler (one of the pongos) took the pics. The guy that said “Jy sal my nie laat lê nie!” said afterwards that he was saying to himself as I approached: “Ek sal nie lê nie, ek sal nie lê nie” (I wont go down, I wont go down) and when I had passed he found himself flat on the ground.

Memories from the past.

Carl Laubin’s Architectural Fantasies

While the subjects of his works are varied, Carl Laubin has become best known for his architectural paintings. Born in New York in 1947, he veered into architectural painting when he was taken on by the London office of Richard Dixon — now part of Dixon Jones, the firm responsible for, among other projects, the Royal Opera House and the redesign of Exhibition Road. With an eye for detail, he has completed capriccios displaying the total built corpus of Hawksmoor, Cockerell, and, most recently, Vanbrugh, while the National Trust also commissioned him to paint a capriccio of all the houses currently within their care.

More of his work can be viewed at the website of Plus One Gallery, and a book of his paintings has been published by Philip Wilson. (more…)

A Mantelpiece

ONE MUST ALWAYS have a mantelpiece. That, at any rate, is my considered opinion. It is a focal point where one can place random objects of vague significance upon it as a salutary reminder of the varied importance of the numerous sectors of one’s life and the gentle interplay therebetween. In my admittedly brief (yet increasingly less brief) existence, I have had several mantelpieces. Indeed, I was even for a year at university in possession of a listed mantelpiece though, sadly, it was abused by the presence of an interloping non-functioning electric heater. But my current riparian London residence is augmented by a number of mantelpieces, one of which fortuitously sits in my own bedroom. While I generally prefer to leave things unexplained, here is a little guide to my mantel as it now stands.

Behind the entire tableaux hangs a French map of Africa I picked up during the summer I lived in Oxford. The recent independence of South Sudan renders it inaccurate, in addition to two or three vexillological changes in its corner display of flags. From left to right, we have the pennon of the Order of Malta in Scotland; the piece of the Berlin Wall my kindergarten teacher brought back from Germany for me; a Rackham postcard from Don Riccardo illustrating depicting a scene from Baron Foqué’s Undine (“Soon she was lost to sight in the Danube”), to which Don Riccardo has added the cryptic line “The fate, it seems, of all Cusack’s loves”.

Next is the glass flask with leather covering I picked up at an antiques place in Millbrook when wandering around hunt country with the Gills; a postcard of Bonnie Prince Charlie sent by the Cap’t as a thank-you note for hosting lunch at Rocca with our favourite ancient veteran of King’s African Rifles; the order of service from the University of St Andrews Alumni Club London carol service; a small bottle of Unicum brought back from Hungary by E.W.; a Marian prayer card from Tom & Alice; a little unpretentious triptych some relative bought; my Order of Malta Lourdes pilgrimage medal; an Infant of Prague retrieved from my grandparents’ house; a St Benedict medal (perhaps obtained at Downside).

The bottle of Boplaas Port was kindly (and perhaps unintentionally) left by one of the previous South African residents of our flat. It was finished off by our Continental correspondent Alexander Shaw and I late one night when he had just alighted the Eurostar and not yet had time to drop his bags off at his grandmother’s place a few minutes up the river on Chiswick Mall. Cornelius Bear is dressed in the red gown of a St Andrews undergraduate. Behind him is a Quebec automobile numberplate and a prayer card from St Philip’s Day 2012 at the Oratory. My Magister Artium diploma is rolled up in its tube next to an empty box of Dunhills purchased in Milan — “Il fumo invecchia la pelle” it warns. Surmounting all is a palm from Palm Sunday at the Oratory.

Politigården

The Police Headquarters, Copenhagen

One of the pleasures of the recent hit Danish television series Forbrydelsen (released in the UK as ‘The Killing’) is the occasional view it provides of Copenhagen’s police headquarters.

Politigården (lit. police-yard) is in a restrained Scandinavian modern classicism and was designed by Hack Kampmann.

It was constructed from 1918 to 1922 but Knapmann died in 1920, and his role as chief architect was assumed by his son Hans Jørgen Kampmann (whose brother Christian was also an architect).

The interior hints towards a variety of styles from Renaissance to Baroque and Art Deco, while the building rises around a large central circular courtyard roughly the same diameter as the Pantheon in Rome.

Some architectural historians consider Politigården the last neoclassical public building in northern Europe (so far, that is). (more…)

In Defence of Orbánisation

The silent majority of Hungarians have at last found a voice in the Fidesz party – and the European Commission don’t like what they are hearing.

by ALEXANDER SHAW in Brussels

In under two years, Viktor Orbán’s regime has reduced the Hungarian budget deficit, reduced personal income taxes, returned the GDP to growth and proclaimed sovereign primacy over supranational diktats. Adopted at the beginning of this year, Fidesz’s new national constitution finally overthrows the Communist era law of 1949. Hungary is the last former East Bloc nation to have achieved this. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that 300,000 Hungarians marched to support their government when the reforms came under fire from the EU in January. It was the biggest demonstration in Hungary since the regime change. The message was clear: Fidesz’s democratic mandate is as mighty as ever and Hungarians want sovereignty. (more…)

The Historical Sale at Adam’s

800 Years: Irish Political, Literary, and Military History – 18 April 2012

THE ANCIENT PRACTICE of lèche-vitrine is one hallowed by time and tradition. I remember one December day I had a lunch appointment with a friend who worked at the late, lamented Anglo-Irish Bank on Stephen’s Green in Dublin and, being early, I nipped a few doors down to the auction house Adam’s to engage in a bit of what I like to call thing-avarice (which the Germans probably have a word for). We do enjoy taking the occasional peek round the Dublin auction houses to see what’s what, and to examine the cabinet of curiosities that come out from ancient houses and rotting flats and appear in these bright places where commerce and refinement play their strange little waltz. When it comes down to it, though, it’s really just about having nice things — the sort of stuff you want lying around the house inexplicably.

Anyhow, the historical auction at Adam’s is coming up on 18 April and sure enough their senior rival Whyte’s is having a similar sale just a few days later on 21 April. We’ll only look at Adam’s here — if we considered Whyte’s as well, we’d be here all day. (more…)

The Hon. Lady Goulding

Grande dame of charity and sometime Fianna Fáil senator who provided a ‘harbour of hope’ for the disabled & represented Ireland in squash

IF, LIKE ME, YOUR Venn diagram shows a massive overlap for the circles representing politics, history, aesthetics, and design, then the Irish Election Literature website is a dangerous place where you can waste many minutes of your day. Not long ago, I stumbled across their collection of electoral bits related to Valerie, the Hon. Lady Goulding — at least I think that’s the proper style, these realms are arcane and murky. She was most often, but incorrectly referred to as Lady Valerie Goulding, the fate of many wives of baronets I’m afraid.

She was born Valerie Hamilton Monckton in 1918 at Ightham Mote (pronounced “item moat”, obv.), the house noted for its Grade I listed dog kennel. Her father, Sir Walter Monckton (later 1st Viscount Monckton of Brenchley) was a trusted friend of Edward VIII, and the teenage Valerie was employed as a messenger shuttling letters between the King’s refuge at Fort Belvedere and Stanley Baldwin in Downing Street. Visiting Fort Belvedere in 1993, Lady Goulding recalled the last lunch she had attended there in December 1936:

She [Mrs Simpson] was leaving that afternoon for Cannes, and everyone was talking about nothing so as to avoid what was on everyone’s mind. But one really nice thing happened: there were four bottles of beer next to my place. The King had remembered that when we were rounding up the ponies on Dartmoor the previous year I had a beer in the pub, and that he had remarked that I was very young to be drinking. It was very touching.

In 1939 she attended the Fairyhouse races and met Sir Basil Goulding at a dinner party. Goulding had significant business interests in Ireland and became known for once entering a bank board meeting on rollerskates. On her second visit to Ireland, they became engaged, and married quickly as the threat of war loomed on the horizon. Sir Basil served in the RAF, rising to the rank of Wing Commander, while Lady Goulding opted for the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry before switching to the Auxiliary Territorial Service. After the war, the Gouldings moved to Dargle Cottage in Enniskerry, Co. Wicklow. (more…)

Tretheague

Stithians, Cornwall

It having just been St Pirran’s Day recently, why not have a look at some Cornish property up for grabs? Just southwest of the Cornish village of Stithians is this curious little house named Tretheague, now up for sale from Savills with seventeen acres attached. Stithians is known for its agricultural show held every July since 1834 and “one of the largest and best-known ‘one-day’ shows in the West Country” according to the agents’ propaganda tells us.

“The Manor of Tretheague” the propaganda continues, “was owned by the ancient Cornish Beville family until the end of the 16th century. Philip Beville of Killygarth died leaving the property to his son in law, Sir Bernard Grenville of Stowe, who sold off various tenements and dismembered the manor as such. The family of Tretheague lived at the property for three centuries until Walter Tretheague died around 1602. They were followed by the Morton Family who did well from mining interests in the county until another wealthy tin adventurer, Nicholas Pearce, who developed Wheal Maudlin at Ponsanooth, took over the old manor in 1690.”

“John Pearce rebuilt the house the year before becoming High Sheriff of Cornwall in 1745 and his descendants sold the property to J M Williams in 1872, another member of a famous Cornish family that prospered from the Cornish mining boom. Under the guise of Williams Cornish Estate the property was sold privately to Bernard Penrose in 1962 who then spent almost 20 years restoring this somewhat unique and unspoilt gem that had remained almost unaltered since the time of its construction.”

“The house standing replaced an Elizabethan house that was recorded as having seven chimneys in the tax of 1660, although only small fragments of mullions and cut and chamfered stone survive. The major rebuild took place around 1744, almost certainly designed and overseen by the famous Greenwich architect Thomas Edwards who presided over several commissions in Cornwall for a period when rich County families and well-to- do mining adventurers felt it necessary to show off their new found wealth and elevation in Cornish society.”

“The house overlooks beautiful parkland which borders the drive and separates the house from the country lane. This parkland has been the scene of summer cricket matches from time to time and now contains individual specimen trees of lime, Canadian maple, beech and horse chestnut.”

“An imposing set of granite steps with wrought iron railings rise to the entrance which is at upper ground floor level. Inside the house much of the original period detail is intact, and on the upper ground floor the hall, panelled dining room and magnificent shallow-rise turning staircase feature fine plaster ceilings with modillions and Rococo detail.”

I like the exterior and setting, but from the photos the house feels curiously small on the inside. I somewhat dislike such primly contained box plans, and prefer a bit of awkward additions and extensions from centuries of use. Treatheague seems a bit too clean cut, but worth a look at least.

State Flags Considered

The famous Matthew Alderman provoked a disputation on Facebook the other day regarding amongst other things (jousting got a mention) the relative merits of U.S. state flags. I touched upon this subject previously in a post discussing the arms of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, when I noted the lamentable tradition in American state flags is for the state seal or emblem to be presented on a blue field. Overall, I have to admit that Maryland has the best flag of any U.S. state: it is heraldic, relatively simple, and overwhelmingly traditional. The Facebook commenting led to an all-out war of annihilation between a lasse of Virginia and one of Maryland on the relative merits of their respective state flags. Right as it is for Virginians to defend the great inheritance of their fair dominion, there is simply no contest here: Maryland’s flag is the overlord.

Just look at Virginia’s (above) state flag! A total yawn-fest, I’m afraid. State seal on blue — how original. It would be far better if they took their ancient coat of arms and followed Maryland’s example by using a banner of arms. In Virginia’s case that would mean a red Cross of St George with the crowned shields of Scotland and Ireland in two quarters and of the quartered French & English arms in the other two quarters. Very handsome.

I don’t really like many other state flags (my geboorteland of New York is no exception: once again a banner of its arms would be much more handsome). Of the few I do enjoy, California rakes highly. It has a certain panache, and the words ‘California Republic’ are a healthy reminder of wherein lies the sovereignty. And interestingly, if the Soviets ever take California (“You mean they haven’t?”) they wouldn’t have to change the flag at all, as it already has a red star.

New Mexico’s is admirably simple and different, but one does worry if it’s a bit too simple: the Zia sun symbol veers eerily close to being a corporate icon. The uber-trad proposal would be to replace it with the yellow-field Cross of Burgundy.

The flag of South Carolina also gets an honourable mention, with its comely combination of palmetto tree and crescent moon. Rendered in red and white instead of blue and white, it is the flag of the Citadel, South Carolina’s military college.

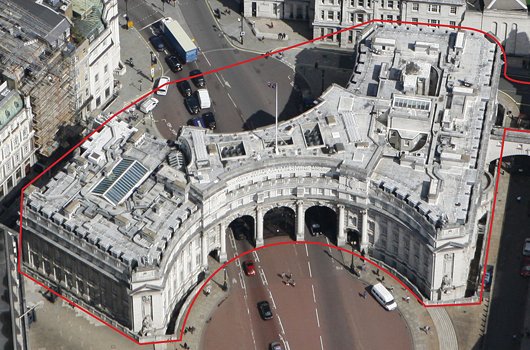

Admiralty Arch for Sale

Sort of: Queen Offers Long Leasehold of Edwardian London Landmark

SIR ASTON WEBB’S great Edwardian Baroque office-building-cum-triumphal-gateway, Admiralty Arch, will be offered up for a long leasehold by HM Government. The Grade-I listed building, constructed between 1910 and 1912, is one of the best-known in London for finishing the long view down the Mall from Buckingham Palace and connecting it to Trafalgar Square beyond. Admiralty Arch features 147,300 square feet across basement, lower ground, ground, and five upper floors.

Savills have been appointed as the sole exclusive agent to seek interest in the long leasehold. “The Government’s objective is to maximise the overall value to the Exchequer from the re-use of Admiralty Arch,” the Savills press release noted, “and to balance this with the need to respect and protect the heritage of the building, now and in the future, enable the potential for public access and ensure awareness of, and be prepared to respond to, potential security implications.”

Our prediction: oil money from abroad will turn it into a hotel. Boring, I know!

Comper in Clerkenwell

The unbuilt Church of St John of Jerusalem

IN THE REALMS of architecture, the unexecuted project has a certain air of fantasy to it — the allure of what might have been. Ranking high amongst my favourite unbuilt proposals is Sir Ninian Comper’s project for the Church of St John of Jerusalem at Clerkenwell. Comper designed the scheme in the middle of the Second World War as a conventual church for the Venerable Order of St John, the Victorian Protestant revival of the old Order of St John (now more commonly known as the Order of Malta) which was banished from England at the Reformation. The design (below) is a Romanesque-Gothic hybrid, a splendidly exuberant cross-fertilisation of two styles more frequently opposed to one another in the minds of most.

One of the proposals for the serious reform of the Order of Malta in Britain is for the Grand Priory of England to divest itself of its interest in the Hospital of St John & St Elizabeth and its associated chapel in St Johns Wood. Owing to a complicated series of events, conventual events are taking place at the Church of St James, Spanish Place already. As the Venerable Order never executed Comper’s brilliant design, perhaps the Order of Malta might consider buying a suitable site in London and making Comper’s fantasy a reality.

A Place in Paris

With a view over the Place des Victoires

If you’re in the market for a little place in Paris, centrally located, Knight Frank has got just the thing for you. Admittedly, it’s only a wing of a larger hôtel particulier on the Rue Vide-Gousset, but it has an enviable view over the Place des Victoires. Mind you, I’ve always been of two minds about the Place des Victoires. I’m not particularly a fan of Louis XIV, whose somewhat silly equestrian statue presides foppishly over the centre of the circus: I’ve always blamed him for the French Revolution, failing to heed Margaret Mary Alacoque’s warnings and all that. But the statue’s only been there since 1828, so perhaps it can be replaced with something better in a suitably classical style. (more…)

Die nuwe Volksblad

Not to be too Gollumesque about things, but I hates it! I always thought the Volskblad (Bloemfontein, daily, Afrikaans, f. 1904, circ. 28,000) had one of the most dignified and handsome banners of all the Afrikaans dailies. The logo of the “People’s Paper” exudes a certain classical dignity and seriousness. Previous banners (see slideshow below) conveyed an individuality. I particularly like the chiseled blackletter typeface used in the second banner displayed below: strength, dignity, tradition, age. (more…)

Happy Christmas

Happy Christmas

and a

Blessed New Year

I wish all our readers the very best for this Christmas season and I hope we will all enjoy innumerable blessings in this coming year.

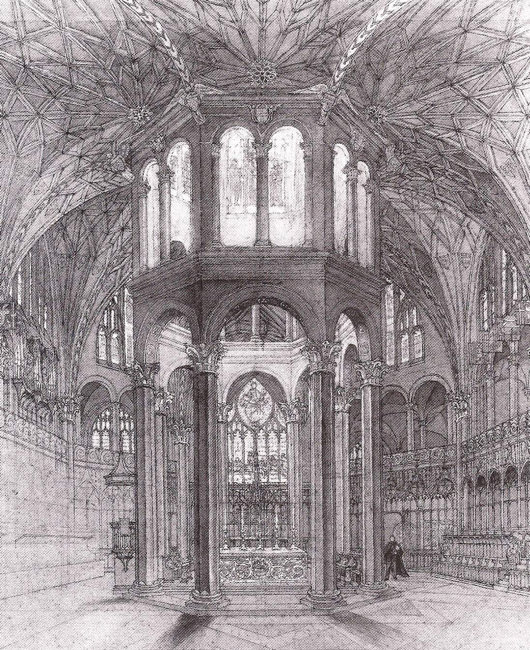

St Andrew’s & Blackfriars Hall, Norwich

NORWICH, THAT CITY of two cathedrals, is known for Colman’s Mustard and the television cook Delia Smith (herself Catholic). Unknown to me until recently is that the capital of one of England’s greatest counties is also home to the most complete Dominican friary complex in all of England. The Dominicans had arrived in Norwich in 1226 — the swiftness with which they reached the city comparative to the foundation of the Order of Preachers is indicative of England’s inherent inclusion in the Catholic Europe of the day.

From 1307, the OPs occupied this particular site in Norwich until the Henrician Revolt, when the friary was dissolved and the city’s council purchased the church to use as a hall for civic functions. The nave became the New Hall (later St Andrew’s Hall) while the chancel was separated and used as the chapel for the city council and later as a place of worship for Norwich’s Dutch merchants. (The last Dutch service was held in 1929).

The complex has been put to a wide variety of uses. Guilds met here, as did the assize courts. It was used as a corn exchange and granary. King Edward VI’s Grammar School began here. Presbyterian and Baptist non-conformists worshipped in various parts during the late seventeenth century. William III had half-crowns, shillings, and sixpences minted here. In 1712, the buildings became the city workhouse until 1859, when a trades school was established the continues today elsewhere as the City of Norwich School. The East and West Ranges are now part of the Norfolk Institute of Art and Design. (more…)

A Breath of Fresh, Northern Air

The Dorchester Review Proves That Canada is Still Thinking

This summer I received an email from my friend Bruce Patterson, all-around nice guy and Deputy Chief Herald of Canada, informing me of a new historical and literary review just founded called the Dorchester Review. Intrigued, I obtained a copy and was pleasantly enthralled with what I found. The first issue of the Dorchester Review contained a variety of thoughtful articles on fascinating subjects. I spent an entire morning sitting comfortably on a café sofa and imbibing the intelligent and enlightening contents of the magazine.

The editors did issue a brief statement explaining the genesis of their new review. They had me at their Pieperian first sentence: “The Dorchester Review is founded on the belief that leisure is the basis of culture.”

Just as no one can live without pleasure, no civilized life can be sustained without recourse to that tranquillity in which critical articles and book reviews may be profitably enjoyed. The wisdom and perspective that flow from history, biography, and fiction are essential to the good life. It is not merely that “the record of what men have done in the past and how they have done it is the chief positive guide to present action,” as Belloc put it. Action can be dangerous if not preceded by contemplation that begins in recollection.

The endeavour of reviewing books, the editors acknowledge, has too often been reduced either to brief puff-pieces in the Saturday insert of the local paper or more high-minded but uncritical praise of like-minded academics for one another. “There are too few critical reviews published today, particularly in Canada, and almost none translated from francophone journals for English readers.” As someone with a lifelong love of Quebec, I am relieved that finally there is a review in my own language willing to take Quebec seriously.

“At the Review,” the editors continue, “we shall praise the good books and assail the bad.”

They also forthrightly explain their rejection of the narrow nationalist perspective that has been on the ascendant in Canada throughout the past century, especially since the foundation of The Canadian Forum. The Dorchester Review effectively throws Canada’s doors open to a more reasoned understanding of the country’s relationship with Europe (Britain and France particularly), America, the Commonwealth, and the world.

But the Dorchester Review is not a publication just for Canadians. There is a great deal of Canada in it, but also a great deal of the world. The second issue (just printed) features articles with titles such as “Why Marx is Still (Mostly) Wrong”, “1789: The First Counter-Revolutionaries”, “What Sort of Autocrats Were the Popes?”, “Can Vichy France Be Defended?”, and “The Scots Fight Back” (the last in response to an article in the first issue: “How the English Invented the Scots”).

Contributing editor Chris Champion is interviewed by CBC Radio here. A number of the contributors (Conrad Black, Paul Hollander, etc.) readers of The New Criterion will already be familiar with. The latest number also includes a book review by this, your humble and obedient scribe.

Head over to dorchesterreview.ca to find out more or subscribe.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories