Errant Thoughts

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The McGillycuddy of the Reeks

How lovely to see a member of the Gaelic nobility – in this case, the McGillycuddy of the Reeks – having a letter printed in the newspaper (Daily Telegraph, Letters, Wednesday 20 December 2017).

His title is somehow the most fun of all the Chiefs of the Names, though not all bearers of the chiefdom have found it amusing. In the early years of the BBC, the ‘Green Book’ instructing comedy producers what they could and could not get away with contained the instruction ‘Do not mention the McGillycuddy of the Reeks or make jokes about his name’. Clearly a protestation had been made.

Looking at the map of Kerry on my kitchen wall, the eye often drifts to McGillycuddy’s Reeks themselves, the “black stacks” amongst which can be found Corrán Tuathail, Ireland’s tallest mountain.

“Get me ze Führer!”

Stereotypes of Nazi generals in British war films

“The reason for my uniform being a slightly different colour to yours

is never explained.”

The British are, of course, obsessed with the Nazis. There are many reasons for this, amongst which we must include the large number of really quite good war films produced during the 1950s and 1960s.

For some indiscernible reason these movies have the virtue of being eternally rewatchable and many a cloudy Saturday afternoon has been occupied by Sink the Bismarck!, Where Eagles Dare, or The Colditz Story.

The genre also deploys with a remarkable regularity a number of familiar tropes of ze Germans which the above clip from a British comedy sketch programme (introduced to me by the indomitable Jack Smith) aptly mocks.

The French Way of War

I’ve  been reading Lartéguy recently so was intrigued to hear of another French writer formed by his military experience, Pierre Schoendoerffer (right).

been reading Lartéguy recently so was intrigued to hear of another French writer formed by his military experience, Pierre Schoendoerffer (right).

In a tweet, the cigarette-smoking Helen Andrews shared an article called What a 1963 Novel Tells Us About the French Army, Mission Command, and the Romance of the Indochina War.

I dislike the romanticism surrounding the magnificent losers vs. ugly victors dichotomy – a magnificent victory is infinitely preferably to both. Hence why my natural Jacobite sympathies are highly qualified by complete and utter disdain for Charlie’s unwillingness to see the task through. (An easy judgement when made from centuries of hindsight, I’ll concede.)

Anyhow, I sent the article to The Major and he proffered this reply:

I was going to say something snide about the French army but to be quite honest I have thought for some time that it is rather better than ours [Ed.: the British]. Their officers are tougher, harder, and more professional than ours – those I encountered professionally certainly were. They are also not infected by the political correctness which is wrecking/has wrecked our army (among other factors).

The distinction between the colonial army and the large conscript army at home is valid. It was the conscript army which was defeated in 1870, 1914, and 1940… not the colonial army to which the modern French army now looks.

It is also true that the US Army don’t do Mission Command well. The Marines on the other hand…

Meanwhile back in the States the prolific Ken Burns has done an eighteen-hour documentary on the Vietnam conflict which allegedly ignores all the scholarly input of the past two decades. Nevermind, we just regret it won’t feature the late great Shelby Foote, who (in Burns’s ‘The Civil War’) spoke with such assurance you imagined he was there.

From Realm to Republic

South Africa’s transition from a monarchy to a republic coincided with a change of currency. Out went the old South African pound (with its shillings and pence) and in came the decimilised rand.

Luckily the republican government had the good taste to commission George Kruger Gray, responsible for the country’s most beautiful coinage, to design the new coins. HM the Queen was replaced by old Jan van Riebeeck, and the country’s arms were deprived of their crown.

Champagne and the World

Champagne can provoke a great deal of philosophy. I’ve often said that champagne and the Catholic faith are the only two universally applicable things in the universe – appropriate for births, deaths, good times and bad, early, late, or a mundane afternoon.

Iain Martin has a brief but excellent piece ‘On Wine’ discussing Churchill’s drinking habits, and wondering whether he really was permanently pissed during the war (unlike the teetotal vegetarian Mr Hitler).

Interesting in itself, but Mr Martin relates a trip to Épernay where he blind tastes a Margaux from 1873. By that time it should have tasted like vinegar but instead it was “beautifully balances and perfectly drinkable”.

Looked after carefully, not shaken about or disturbed unnecessarily, it evolved and endured. It retained its essential characteristics, giving pleasure to later generations. If only we nurtured political institutions and good government according to the same principle.

Nothing could better show the essence of a sound worldview.

South Africa in the Old Days

This historical film about the early days of the Cape was probably produced for the van Riebeeck tercentenary festival of 1952.

The clip here covers the days of Governor Willem Adriaan van der Stel, depicting them as carefree days of harmony and merriment in South Africa – in contrast to Europe where war and persecution reigned. Doubtless this was how the apartheid government sought to portray South Africa at the time: a haven of peace and prosperity in contrast to a Europe still recovering from war, with half the continent now under the Soviet boot.

Simplistic propaganda of course, but the film conveys a certain charm regardless, as does almost every depiction of the Cape before the British. The sight of geese flocking before an old Cape Dutch homestead (circa 7:00) never fails to touch the Cusackian heart…

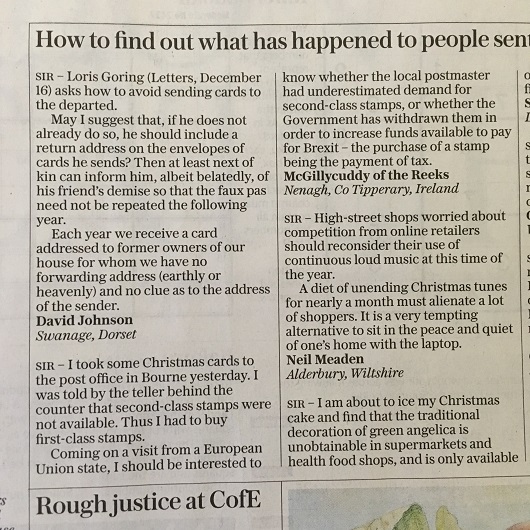

The Earl Attlee

At Chartwell one weekend in Churchill’s presence, Sir John Rodgers made the mistake of referring to Clement Attlee, wartime deputy prime minister and postwar prime minister, as “silly old Attlee”. Churchill was having none of it.

“Mr Attlee is a great patriot,” he said. “Don’t you dare call him ‘silly old Attlee’ at Chartwell or you won’t be invited again.”

The leader of the Conservative party and the leader of the Labour party were obvious political rivals but developed a great bond by their shared experience in the cross-party War Cabinet.

En route to a dinner party the other night I happened to run into Attlee’s greatgrandson (an old friend) on the upper deck of the 414 bus. It reminded me of this photo (above) printed in the Observer. When the great bulldog went on to his eternal reward in 1965, the incredibly frail Earl Attlee insisted on attending the state funeral in St Paul’s Cathedral. Though younger, he only managed to outlive him by two years.

Attlee had been raised to the House of Lords (where he spoke against Britain joining the EEC) in 1956 and, rather appropriately, he chose as the motto for his coat of arms Labor vincit omnia — Labour conquers all.

Challoner’s House

Challoner’s House — Rather humble for an episcopal palace, but such was the function of No. 44, Old Gloucester Street in Holborn during the time of Bishop Richard Challoner.

If it seems an odd spot for London’s Catholic bishop, it can be explained by its close proximity to the chapel of the Sardinian Embassy off Lincoln’s Inn Fields. At this time, of course, the Mass was still illegal and the only places Catholics in London could worship were the embassies of the Catholic nations. To protect the underground bishop, the house in Old Gloucester Street was actually rented in the name of his housekeeper, Mrs Mary Hanne.

After a perfect breakfast on Saturday morning the sun was shining so I decided the three-and-a-half miles home from St Pancras were best managed on foot. If architectural or historical curiosities are your fancy then foot is the way to travel, and so it was by pure chance that I stumbled upon No. 44. It seemed particularly appropriate that the night before a whole gang of us — Brits, Swedes, Italians, etc. — had been drinking in the Ship Tavern in Holborn where Bishop Challoner was known to offer the occasional clandestine Mass. (more…)

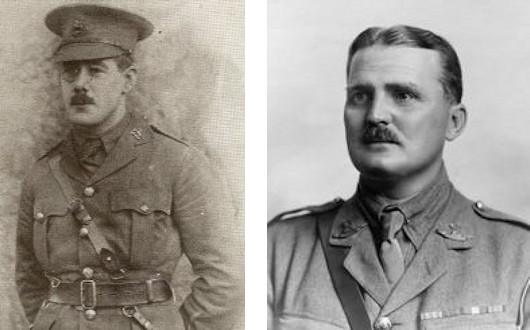

South African VCs in the Russian Civil War

The South African contribution to the Russian Civil War is not very well known, nor particularly well researched by historians of the period. Several South African officers who found themselves in Europe by the time of the armistice ending the Great War volunteered to serve in Russia fighting the Bolsheviks — either with the Allied force there or with the White forces themselves.

Among the South African volunteers were two winners of the Victoria Cross — Major Oswald Reid (above, left) of Johannesburg, and Lt Col John Sherwood-Kelly (above, right) from the Eastern Cape.

The South African aviation pioneer K R van der Spuy — who ended up a major general — managed to serve from the early days of 1914 all through the First World War. His engine failed in Russia, however, and he was taken prisoner after a forced landing in Bolshevik-held territory. The Soviets released him from imprisonment in 1920.

As Cdr W M Bisset wrote elsewhere: “Despite the harshness of the Russian winter and the growing prowess of the Red Army, South African officers were able to make a valuable contribution to the operations of the Allied and White Armies which is well illustrated by the important posts which they held and the awards they received.”

An Hollandic Hovel

A friend sent this link to a property for sale in Amsterdam. I can easily imagine getting a lot of writing done while listening to LPs of baroque music (my latest craze) through a haze of cigarette smoke in a garret like this.

Its drawback is that it’s on an actual street — what’s the point of living in Amsterdam if you’re not on an actual canal?

Holy Trinity Kingsway

Holy Trinity, Kingsway

Not much information is available about this church. The architect was John Belcher but the ambitious tower was never built, nor was there much money to complete the interior.

After it was made redundant in the 1990s the church was demolished — except for the façade so obviously influenced by Santa Maria della Pace.

Stockholm in the Swinging 60s

The Solemn Opening of the Riksdag was the state opening of Sweden’s parliament, seen here in a recording from 1960 during the reign of Gustaf Adolf. Years ago I wrote about Oskar II’s opening of parliament.

Alas, all this was done away with as part of the constitutional innovations of 1974, and the Swedish legislature is now opened with a much simpler ceremony.

via Karl-Gustel

1950s Ireland, the Church, and the Arts

Sitting in Dublin Airport waiting for a flight last week I picked up a copy of the Irish Arts Review which featured a number of interesting pieces (including something by our own Dr John Gilmartin).

Among the articles was an interview with the artist and printmaker Alice Hanratty (born 1939), a member of the Aosdána as well as of its governing council the Toscaireacht.

It was interviewer Brian McAvera’s question to Ms Hanratty about Ireland in the 40s and 50s and her response that proved most interesting.

BMcA: Artists, nevermind historians, often talk about the dark days of the 1940s and 1950s in Ireland: petty, parochial, restrictive, dominated by the Catholic Church, politically conservative and sexually repressed. How did you see this period and was it in any way formative for you as an artist?

AH: I have some experience of the period in question and don’t really recognise the description that you quote.

As far as the arts are concerned you must remember that important Irish poets, dramatists, and novelists, and also painters and sculptors worked at that time. Brian Fallon discusses all that in his An Age of Innocence. As for ‘politically conservative, restrictive, dominated by the Catholic Church’ these I think are quite sweeping statements by people who did not actually live at that time and are re-stating a received perception which is inaccurate.

As for domination by the Catholic Church, to some degree people allowed themselves to be dominated. They were OK with it. It suited them. It provided answers about the imponderables such as death. Nor should it ever be overlooked that the vicious war waged against the Irish people and the practice of their religion by way of the penal laws have had a huge detrimental effect on the national psyche which is not yet dispersed even in the 21st century.

As for political conservatism (don’t start me), that was established by the Free State Government in the 1920s making a deliberate and successful move to stamp out any form of socialism that might develop. Of course the Church was pleased to be of help there, but was not the instigator. President Higgins made reference to this period in one of his 1916 commemoration addresses, so anyone seeking enlightenment in these matters would find it there.

Were the 1940s and 1950s influential for me as an artist? No. I was too young and was not looking outwards for inspiration.

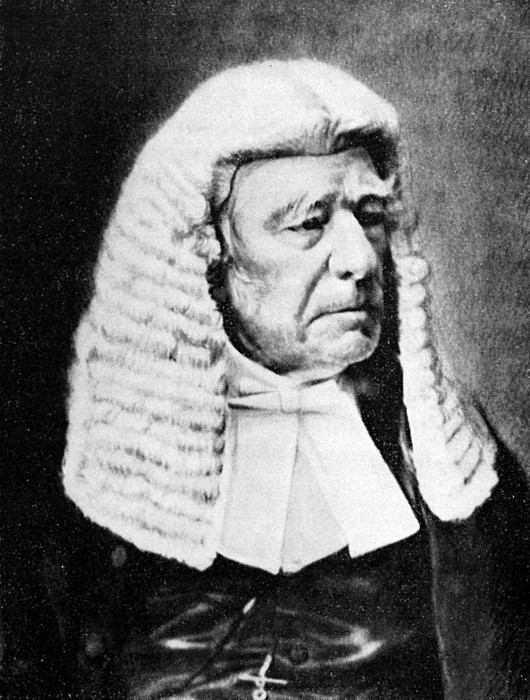

Sir Christoffel Brand

Look at that cragly visage! It belongs to Sir Christoffel Brand, the first Speaker of the House of Assembly in the Cape Parliament.

Brand was born in Cape Town in 1797 and left for the Netherlands in 1815, where he studied at Leiden. In 1820 he was awarded a doctorate in law based on his dissertation Dissertatio politico-juridica de jure coloniarum on the legal relationship between colonies and the metropole, and returned to the Cape. (more…)

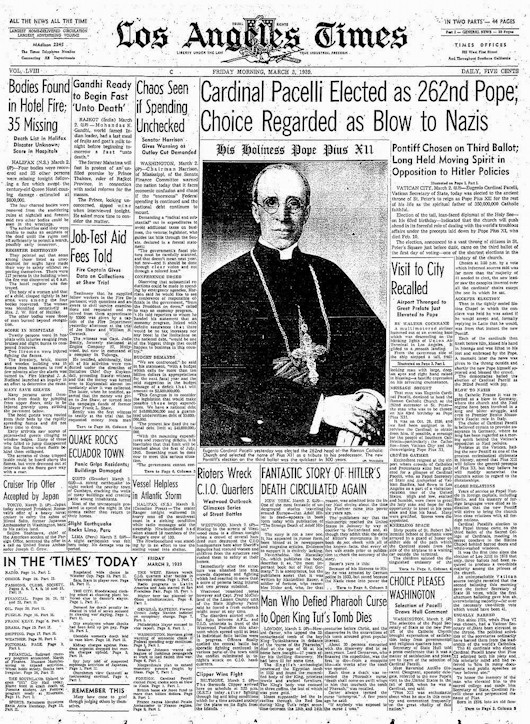

The L.A. Times on Papa Pacelli

How News of the Election of Pius XII was Received in 1939

The case against Pope Pius XII, accusing him of complicity in the crimes of Nazism, has been so thoroughly debunked — by Jews like Gary Krupp and Rabbi Dalin more than any — that it is no longer even worth refuting.

Still, it’s interesting to read the Los Angeles Times’s coverage of his election as Supreme Pontiff in the difficult year of 1939:

BLOW TO NAZIS

… The choice of Cardinal Pacelli is believed certain to provoke annoyance in Germany, where he long has been regarded as a moving spirit behind the Vatican’s opposition to Nazi policies.

As the news report goes on to note, Cardinal Pacelli was elected in only three ballots — the quickest papal election since that of Leo XIII in 1878.

Christmas on College Green

There are some good (if brief) shots of the Irish House of Lords chamber in this Christmas ad for the Bank of Ireland, 0:35-0:45.

The former Irish Houses of Parliament on College Green in Dublin were the first purpose-built parliament building in the world, and were purchased by the Bank of Ireland after the parliament was abolished by the Act of Union in 1800.

Unfortunately a condition of sale was demolishing the elegant octagonal Commons chamber at the centre of the building, to prevent it being used in the effort to have the Act of Union repealed.

Sir Thomas Cusack (1505-1571) has the distinction of having at times served as the presiding officer of both the upper and lower houses of the Irish Parliament. From 1541-1543 he was as Speaker of the House of Commons, in which role some scholars argue he was a prime mover behind the legislation erecting Ireland as a kingdom.

In the following decade he served as Lord Chancellor of Ireland, presiding in the House of Lords, from 1551 until 1555 when revelations about his involvement in the creative finances of Sir Anthony St Leger’s viceregal regime brought about Sir Thomas’s dismissal and (temporary) imprisonment.

He returned to favour when the Earl of Sussex was appointed viceroy, but never again held high office.

Of course, all that was before this neoclassical building was erected, when Parliament met mostly in Dublin Castle.

Hamburger Abendblatt

The German advertising agency Oliver Voss created this series of ads for the Hamburger Abendblatt, Hamburg’s daily evening newspaper.

Oliver Voss have done web and print ads for the Abendblatt before but the illustrations in this series of posters strike a jovial pose, feeling perfectly contemporary while still informed by a sense of the 1950s.

The summery beach scene is my favourite.

Mendicant Architecture in Mediaeval Oxford

An interesting video from two American academics on the subject of Mendicant architecture in mediaeval Oxford, with some three-dimensional theoretical reconstructions of the Dominican and Franciscan houses in the city.

Both orders returned to Oxford in the twentieth century. The Capuchins refounded Greyfriars in 1910 and it was recognised as a permanent private hall (PPH) of the University in 1957. Its end as an academic institution was announced sadly on its fiftieth anniversary in 2007, but Greyfriars continues as a Capuchin friary.

Blackfriars under the Dominicans is still going strong, exercising a triple function as a priory of the Order of Preachers, a house of studies for the English province of the Order, and a PPH of the University of Oxford.

Judging Dress

After some absence, The Sybarite has returned and, in A Love Supreme, he weighs in on the very important matter of judicial dress.

I am, it will surprise no-one to know, deeply traditionalist in such matters. I can see the argument for discarding formal court attire in cases involving children, who might be intimidated by wigs and gowns (as a child, I myself would have been as happy as a pig in the proverbial). But I feel strongly that “work clothes”, whether worn by judges, barristers, politicians or clerks in Parliament, are important. They are part of the persona. You are not Alf Bloggs, you are Mr Justice Bloggs and you are performing an important public role. When you put on the clothes, you put on the role. Of course, I am fighting a rearguard action here – I know that the tide of public opinion is against me. If the clerks at the Table in the House of Commons still wear wigs in ten years’ time, I will be (pleasantly) surprised.

As the Supreme Court was set up in the modish New Labour years, it was inevitable they would dispense with much of the ceremonial. The Justices wear lounge suits to hear cases, though I think in some cases the barristers still wear wigs and gowns. The one concession has been the black-and-gold gowns which the Justices don for special occasions. These are fine so far as they go – and, as observed above, Lady Hale of Richmond likes to accessorise hers with a Tudor bonnet – though they bear on the back the badge of the Supreme Court, which I think looks a bit tacky and smacks of footballers’ names and numbers on the back of their shirts. But they also look a bit odd worn over lounge suits or equivalent. At least successive Lord Chancellors since the role was recast by Blair have retained formal court dress for high and holy days. Mind you, the current occupant, Miss Truss, does look a bit like the principal boy in a pantomime when she wears knee breeches. But fair play to her for continuing to wear the traditional robes, even if the full-bottomed wig seems now to have gone the way of the dodo.

It could be worse. The Supreme Court Justices could wear ghastly zip-up gowns like their American counterparts – you just know they’re made of nylon – over their suits, though I have some time for Justice Ginsberg for adding a lace jabot to tidy up her garb a little. But ceremonial is something that Britain does so well. The Supreme Court could have looked so much better with Justices in gowns and traditional judicial clothing. A wig here and there wouldn’t go amiss.

I couldn’t agree more. Especially on the matter of the badge of the Supreme Court on the back on the gowns, which is simply naff. (See image below.)

But why do the justices of the Supreme Court have (what I think of as) chancellorial gowns anyhow? What is the origin of this style of black-and-gold gown? Did it start with the Lord Chancellor and spread to the Speaker or vice versa? Or have some species of judge always worn chancellorial gowns? The chancellors of universities have likewise adopted it, though its precise form varies from institution to institution, as one might expect in matters of academic dress.

Incidentally, I was speaking with Bob Geldof the other day about Senator W. B. Yeats, about whom Mr Geldof has done a documentary. As we were discussing Yeats’ contribution to the Irish Senate, Mr Geldof mentioned that Yeats had been in discussions with Hugh Kennedy, the Chief Justice of the Irish Free State, about introducing new designs for Irish judicial dress. The results, according to just about everyone, left much to be desired and so the British tradition carried on for the most part. As is so often the case, doing nothing is the least bad option.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Gellner’s Prague December 19, 2024

- Monsieur Bayrou December 18, 2024

- Dempsey Heiner, Art Critic December 17, 2024

- Vote AR December 16, 2024

- Articles of Note: 12 December 2024 December 12, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories