Errant Thoughts

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Buchan in Quebec

While the Salon bleu in Quebec’s parliament used to be green, the Salon rouge has kept its lordly colour. Conservative Quebec was the last of the Canadian provinces to abolish its unelected upper house which faced the chop in 1968, that year so beloved of duty-shirkers and ne’er-do-wells.

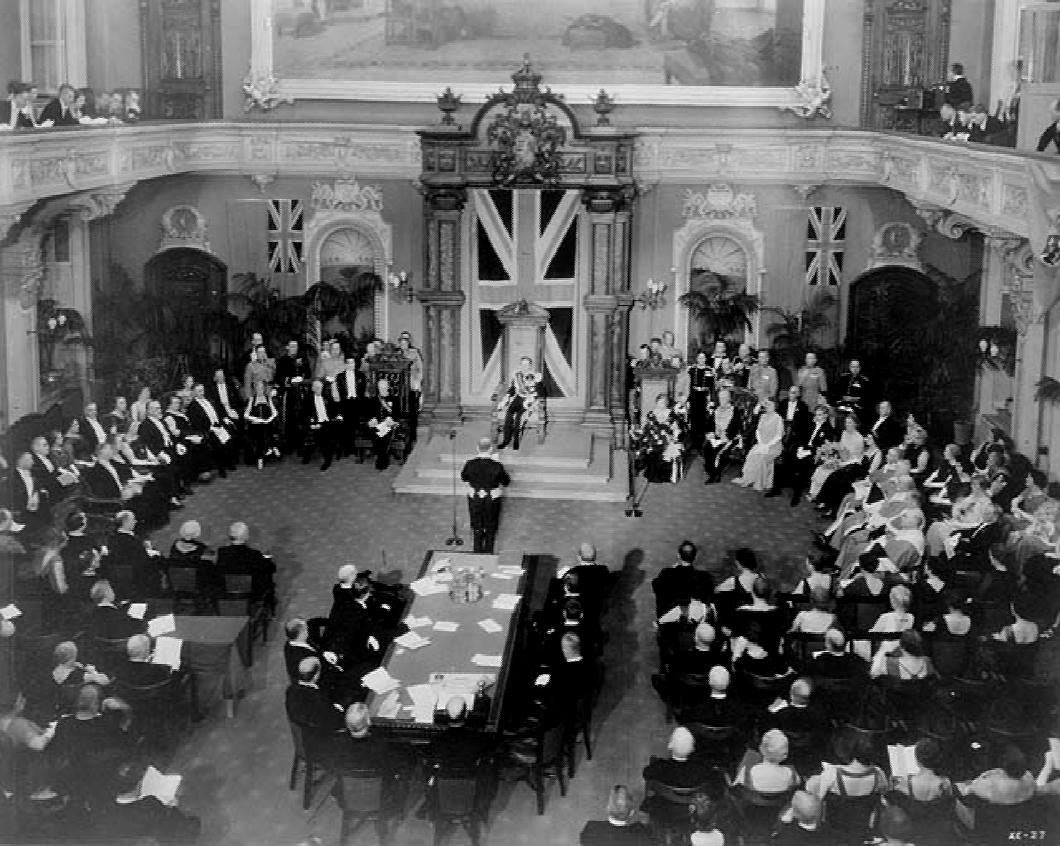

Thirty-three years earlier, the Salon rouge was the scene of a more regal ceremony: the official installation of the Scots writer and statesman John Buchan as Governor General of Canada. Being a Presbyterian with an in-built (but in his case only occasional) tendency to dourness, Buchan wanted to go as an ordinary commoner but the King of Canada insisted on a peerage for his viceregal representative in the dominion.

Thus it was Lord Tweedsmuir who arrived in Quebec in 1935 and was installed as Governor General in the Salon rouge on All Souls’ Day of that year. Above, the Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King gives an address after the swearing-in.

Buchan proved an influential Governor General and helped set the tone of Canada’s monarchy in the aftermath of the 1931 Statue of Westminster that recognised the distinct nature of the Commonwealth realms. He also orchestrated the King’s successful 1939 trip across Canada — which also featured the King and Queen holding court in the Salon rouge of Quebec’s Parliament.

By the time of his death in post in 1940, John Buchan had become His Excellency The Right Honourable The Lord Tweedsmuir GCMG GCVO CH PC. Not a bad end to a good innings.

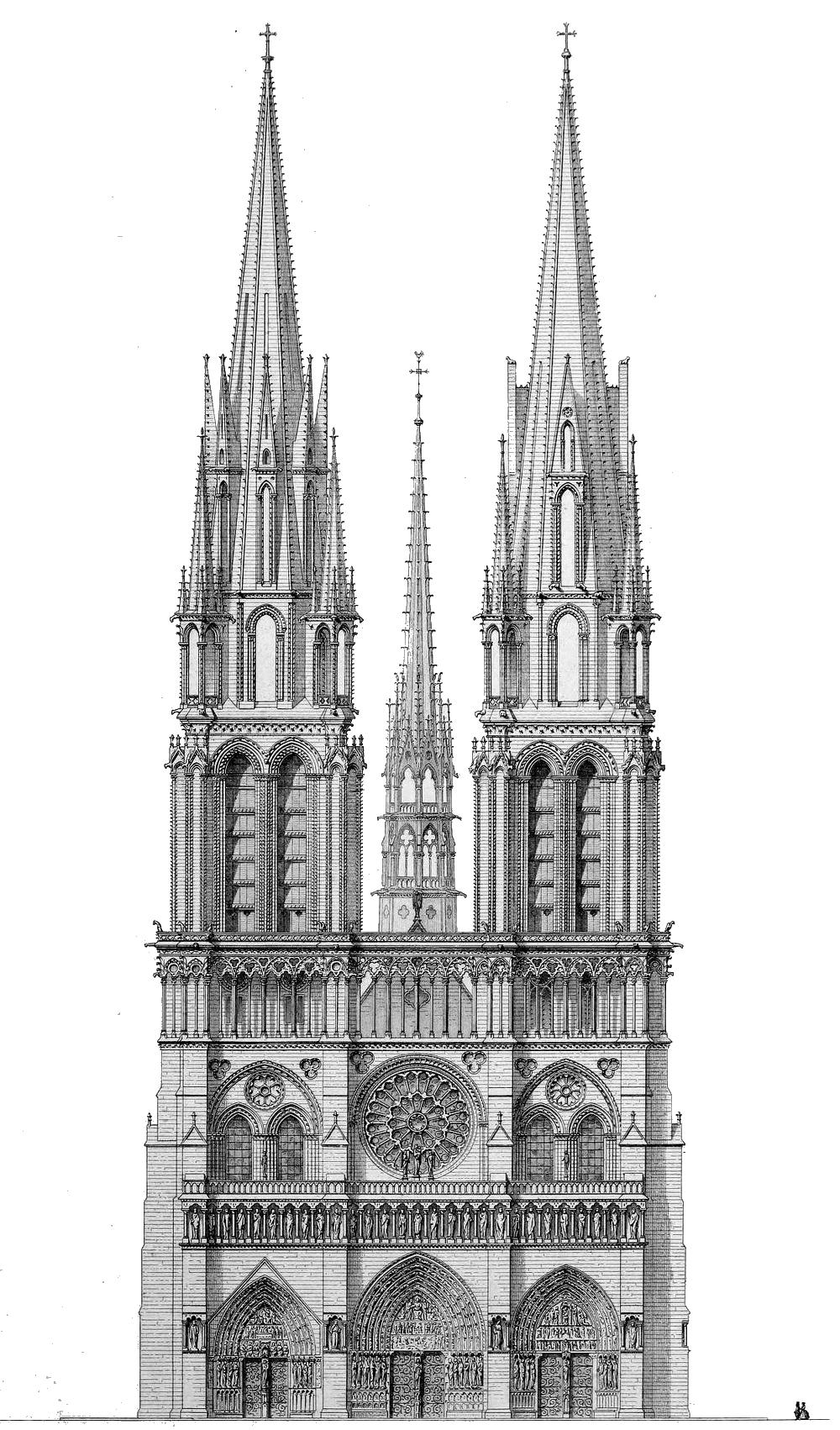

Notre-Dame de Paris

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

1844

Portsmouth Pachyderm

Leach (centre) on being made cadet captain at the Royal Australian Naval College in 1944

A delightful episode is relayed in the Daily Telegraph’s obituary of the late Vice-Admiral David Leach of the Royal Australian Navy.

Leach was the last RAN Chief of Naval Staff to have served in the Second World War but the incident in question dates from the 1950s when he was at the gunnery school in Whale Island in Portsmouth Harbour here in England:

In 1955 he was the course officer for a class of sub-lieutenants who decided to have some fun on their last morning parade, on April 1, by bringing a circus elephant on to the island. The duty officer, warned of the elephant’s approach by the bridge sentry, thought that his leg was being pulled and gave the order to let the pachyderm proceed.

Subsequently the class marched on to the parade ground with the elephant in their midst, surmounted by a mahout dressed as a sub-lieutenant. The beast, being well-trained, picked up the band’s marching step nicely, but Captain “Bunjey” Rutherford, the saluting officer in command of Whale Island, was not amused.

Leach had not been party to the April Fool’s joke, but later that morning, when he took the class results to the captain, he had placed Sub-Lieutenant L E Fant at the top. Rutherford was still not amused, demanding “Fant? Fant? Who’s this feller, Fant?” When the news reached the Admiralty, the Second Sea Lord took a personal interest and called Rutherford to announce, somewhat unkindly: “This is a trunk call.”

R.I.P.

Articles of Note: 5.II.2020

• Some enthusiasts like to go bird-watching, but James Panero of The New Criterion likes to go house-watching. “[O]ur country is fertile ground for good house-watching. Fine examples, of just about any style of any period, abound. What stories they tell if only we listened to their calls.”

• Psephologists are still extrapolating ideas and conclusions from the results of December’s general election here in the UK that handed Boris Johnson a handy majority. One of the most important analyses comes from the philosopher John Gray in the New Statesman: Why the Left Keeps Losing.

• For years, EU leaders have insisted that Brexit would be a disaster for Britain, leaving your country hopelessly isolated, Alexander von Schoenburg, the editor of Europe’s highest-selling newspaper, reports from Berlin. “According to the relentless propaganda of the pro-EU cause, Europe would forge ahead on the global stage, ever more united, while the UK would slide into insularity and decline. But that narrative is starting to look like a delusion.”

• British liberals have created a Europe of their imagination, Ed West writes at UnHerd. But how closely does it resemble reality?

• As the founder of the Anglo-Gaullist Working Group I often ask myself “What would de Gaulle do?” James Pinkerton (the American Conservative) argues that when it comes to Afghanistan, the great Frenchman would advise President Trump to stand his Deep State antagonists down and bring the troops home.

• For centuries Spain faced a perfect storm of enemies that fostered an anti-historical legacy of lies collectively known as the Black Legend. In the University Bookman, Alberto M. Fernandez reviews the surprise Spanish best-seller written by a woman who, according to one newspaper, “has liberated thousands of ideological hostages from a national cancer”.

Articles of Note: 11.XII.2019

• The 1930s Oxford social anthropologist J.D. Unwin studied five thousand years of human existence and discovered you can either have a high level of cultural achievement or widespread sexual freedom but never both. Kirk Durston explores why sexual morality may be far more important than you ever thought.

• America’s secular liberalism isn’t secular at all: it is merely the latest stage in the adaptation of an inevitably deracinated Protestantism, Patrick Deneen argues.

• René Rémond’s model of France’s three right wings — Legitimist, Bonapartist, and Orleanist — is breaking down because, Luke Nicastro argues, Emmanuel Macron is co-opting both Orleanists and Gaullists into his electoral family.

• And finally, a historic note, it’s been more than a quarter-century since the late Anthony Lejeune went on A Tour of New York’s Clubland.

The Manor House

For devoted fanatics of Netherlandic architecture — I’m sure you’d count yourself as one as much as I do — a curious example of Dutch revival architecture can be found at No. 316 Green Lanes in the Borough of Hackney. Alighting from Manor House tube station the other day I was surprised to find myself confronted by a fine building which, it turns out, used to be the pub that gave its name to the Underground station.

The first ‘public house and tea-gardens’ of that name was built in the 1830s, and in 1843 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert stopped there for a change of horses. This tavern soldiered on until the arrival of the Piccadilly line which necessitated street widening and the demolition of the pub in 1930.

It was rebuilt in a very handsome brick Netherlandic revival in 1931 and continued on as a pub supplied by the London brewers Watneys.

A purist would object that the style of windows on the gables suggests a vulgar pakhuis (warehouse) on the Amstel while the stepped gable itself is more informed by domestic architecture. But is the privilege of architectural revivals to mix and match, so I don’t think we should complain.

Evidence suggests the pub shut in 2004 and the building was converted to its current retail use.

Alas, I can find no record of the architect, and the building remains un-listed, but I’m glad Hackney is home to this happy Hollandic interloper.

Articles of Note: 22.XI.2019

• In Spiked, James Heartfield urges us to spurn Labour’s counsel and instead stop apologising for the past.

• Michael Brendan Dougherty in National Review wonders if Republican Missouri senator Josh Hawley might be the next Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

• Why would an Eton- and Oxford-educated man assert he ‘supports’ Aston Villa, a football team based in a slum in Birmingham, a city with which he has no connection? Theodore Dalrymple ponders David Cameron’s Big Lie at Law & Liberty.

• At the American Conservative, Rod Dreher ponders the radicalism of today’s left and whether its religious fervour to deny scientific realities like biological sex is driving Trump-hating lefties to back the Donald for president.

• And, for a decent long read, politics professor Daniel E. Burns examines how critics and defenders of liberalism often argue past one another:

It refers, on the one hand, to a set of political practices, and on the other hand, to a political theory that purports to explain those practices. Defenders of liberalism are thinking first and foremost about liberal political practice, which they (almost all) defend by drawing selectively on liberal theory. Critics of liberalism are thinking first and foremost about liberal political theory, which they (almost all) attack by pointing selectively to liberal practice.

In National Affairs, it’s a question of Liberal Practice v. Liberal Theory.

The politics of parliamentary colour

When Quebec’s « Salon bleu » was the « Salon vert »

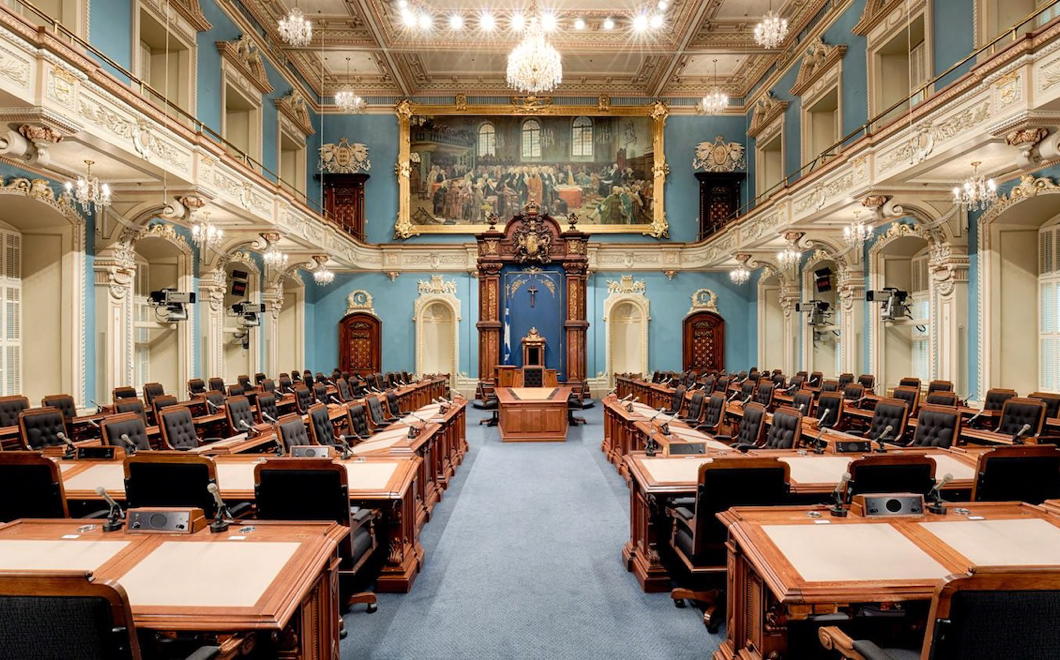

One Westminster tradition replicated in many times and places across the Commonwealth is a convention of colour: the lower house of a parliament is decorated in green, while the upper chamber is decorated in red. This reflects the green benches of the House of Commons and the red ones of the House of Lords.

Officially the plenary chamber of Quebec’s unicameral parliament is boringly the salle de l’Assemblée nationale but because of the colour of its walls it is more often known as the Salon bleu. One’s never surprised when Quebec bucks a trend or (more specifically) rejects an Anglo convention but it turns out the province’s plenary chamber did in fact used to be green until relatively recently.

When the members of the Legislative Assembly (as it then was) first convened in the Hôtel du Parlement in 1886 the walls were actually white. By the opening of the 1895 session the desks had been reappointed in green, but Le Soleil still made reference to the room as the “chambre blanche”. It was only in 1901 that the room was painted a “soft green” and the carpets and other furnishings changed accordingly. It even made an appearance in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1953 film “I Confess”.

From then the chamber was a Salon vert until 1978, when the decision was taken to begin broadcasting the proceedings of the Assemblée nationale.

The television specialists complained that the dark green of the chamber was not visually conducive to the TV cameras available at the time and, looking at the evidence from the 1977 test session (above), one can see their point. Walls of either beige or blue were the options recommended in an official report, and unsurprisingly the national colour was chosen.

The historian Gaston Deschênes has mentioned the technical requirements of broadcasting also coincided with a desire to break with a “British” tradition. Certainly the government of the day, René Lévesque’s Parti Québécois, didn’t mind the change, while Maurice Bellemare — “the old lion of Quebec politics” and sometime leader of the old Union nationale — was deeply pleased that the chamber adopted the colour of Quebec’s flag.

So the walls were repainted sky blue and the furnishings changed accordingly, resulting in the Salon bleu we know today (below).

A tweet from the Assemblée’s official account shows two photos looking towards the chamber’s entrance from before (above) and after (below) it was made ready for television.

All the same, green is not universal amongst Commonwealth lower (or only) chambers. It’s not even universal in Canada: Manitoba joins Quebec in its azure tones while British Columbia’s is red-dominated.

Quebec was the last of Canada’s provinces to abolish its upper house, the Legislative Council, in 1968 (at the same time the lower house was renamed the National Assembly). The Legislative Council’s former meeting place is, of course, red, and the Salon rouge is used for important occasions like inductions into the Ordre national du Québec or the lying-in-state of the late Jacques Parizeau.

Angela Wrapson

In Rome the other week I was sorry to hear from a mutual friend that Angela Wrapson had died. She had been fighting cancer for a while, but she was quite a fighter and was one of those people you thought would always go on.

Angela was, amongst many things, a fixture of that strange yet familiar galaxy known as the Scottish arts world. She was, for example, director of the Stanza poetry festival for some years.

She was a keen listener, a good conversationalist, and a very welcoming hostess in the wing of Brunstane House that she and her husband George bought back in the 1970s.

From 2015 to 2017, George was the MP for East Lothian and I am still ashamed in those two years I never managed to reciprocate Angela and George’s hospitality by having them round.

Nonetheless, I was pleased to see she got the plaudits she deserved with obituaries in the Scotsman, the Times, and the Herald.

May she rest in peace.

What do Namibians know of Germany?

Namibia spent more than twice as long under South African administration then it did when it was German South West Africa, but its formative years under the Germans continue to have an influence.

For one thing, you can stumble around streets marked Zeppelinstraße and Bismarckstraße, not to mention the quite quaffable beer the country produces. Germany’s most remembered act in Namibia, alas, is the massacre of the Herero tribe, whose women are today known for their colourful pseudo-Victorian traditional dress.

Still, a third of the country’s white population are of German descent and German was an official language until 1990, though Namibian Black German (which linguists debate whether it is a dialect or a pidgin) is now nearly extinct. Most German Namibians today would speak Afrikaans on an everyday basis and have a strong grasp of English too.

But what does the average Namibian on the street know of Germany? In the above video a man goes about asking precisely that. Particularly interesting is that moneyed Frankfurt seems to be much better known than the political capital of Berlin. If only there was a video asking Germans what they know of Namibia…

Sir John Soane

Sir John Soane still looms over the intervening centuries of architecture and design in Great Britain, but I’ve never actually known what he looked like. Apparently this is him, in an 1804 portrait by William Owen.

Everyone’s been to his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but Pitzhanger Manor, his place in the country (though Ealing hardly seems rural today) was recently reopened after serious conservation works ongoing since 2015.

Hope to pay it a visit soon.

The Dawn of Da’esh

Patrick Cockburn, 192 pages, £9.99 (Verso Books, London)

words that flow confidently off the page and exude a sense of first-hand knowledge and on-the-ground insight, it’s easy to see how Patrick Cockburn has attained his reputation amongst those in the know as the foremost and most authoritative Western correspondent in the Middle East today. The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution (Verso Books, February 2015) attempts to sketch out the meteoric rise of the soi-disant caliphate’s black-clad gunmen and the factors which have facilitated it. This is no easy task, and while Cockburn does not quite achieve it, his effort is deeply informative—it is hard to imagine anyone could do better than he has in relaying the astounding complexity of the situation in Iraq and Syria today.

words that flow confidently off the page and exude a sense of first-hand knowledge and on-the-ground insight, it’s easy to see how Patrick Cockburn has attained his reputation amongst those in the know as the foremost and most authoritative Western correspondent in the Middle East today. The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution (Verso Books, February 2015) attempts to sketch out the meteoric rise of the soi-disant caliphate’s black-clad gunmen and the factors which have facilitated it. This is no easy task, and while Cockburn does not quite achieve it, his effort is deeply informative—it is hard to imagine anyone could do better than he has in relaying the astounding complexity of the situation in Iraq and Syria today.

Much of the novelty of ISIS lies in the suddenness of their appearance and the continuous string of victories they have amassed. Cockburn is quick to point out that much of this is propaganda: ISIS has been a player in the region for years, but mostly as an authorised bin Laden franchise founded by the Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and under the name of Al-Qaeda in Iraq. Following al-Zarqawi’s death, the Sunni jihadist group transformed into the Islamic State in Iraq and proclaimed its new leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi the ‘emir’, expanding operations into Syria by 2013.

Despite numerous successful terrorist attacks and assassinations, it is the capture of Mosul in June 2014 which Cockburn singles out as the start of ISIS as the phenomenon we are experiencing today. This stellar rise has yet to prove fully meteoric in the sense that, while their onward march has ground to a halt at Kobane, ISIS has stubbornly refused to burn out and fade away. This has been contingent upon an alignment of factors which might be oversimplified into three: the endemic corruption of the Iraqi state, the astounding stupidity of Western powers, and the entrenched sectarianism of Iraqi society.

As one of the most central institutions of the state, the melting-away of the Iraqi Army’s resistance to ISIS has been crucial. It is difficult to overestimate the vast scale of corruption in the Army. Military units often include large numbers of troops that exist only on paper. Command of a division comes with a high pricetag. Having borrowed the money to pay for it, divisional commanders then require steady income streams to pay back the loan. Setting up roadblocks to extort money from travellers is an easy task for an armed force, but the possibilities are numerous.

A retired Iraqi general tells Cockburn the rot first set in when, in 2005, the Americans demanded the Iraqi Army outsource food and logistical supply:

“A battalion commander was paid for a unit of 600 soldiers, but had only 200 men under arms and pocketed the difference, which meant enormous profits.”

In Mosul, Cockburn points out, only one in three of the soldiers meant to be there were physically present, the rest having payed up to half their salaries to be on permanent leave.

Endemic corruption of this kind has been fostered by the complacency of the governing elite. A Turkish businessman was ruffled when a local ISIS leader demanded $500,000 per month in protection money. “I complained again and again to the government in Baghdad,” he relates to Cockburn, “but they would do nothing about it except to say that I should add the money I paid to al-Qaeda to the contract price.” Such an attitude hardly inspires confidence in the state.

As ISIS gained ground across Iraq, the Baghdad elite seemed only to increase its insularity, acting as if nothing was wrong. “When you speak to any political leader in Baghdad,” an ex-minister says, “they talk as if they had not just lost the country.”

“ISIS,” Cockburn points out, “are experts in fear.” YouTube has been deployed with a methodical exactness towards this end. The talking heads who’ve preached the gospel of new media as breaking down barriers and leading to an immanent global liberation have plainly failed to grasp that these new forms of communication can be expertly employed by forces intrinsically opposed to their vision of a liberal utopia.

While the Shi’ites have long been in the majority, the Sunnis were top-dog under Saddam, widely favoured and occupying places of power and authority. With Saddam toppled and democratic elections now forming the basis of the state’s legitimacy, the numerical strength of the Shia has handed the state to Shi’ite political forces fearful of a return to the old days. When Sunnis complain of violence, intimidation, and discrimination at the hands of the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad, Shi’ites don’t see the Sunnis as reacting to oppression but as plotting a return to their former dominance.

This de-legitimisation of the official state in the eyes of Sunni Iraqis has provided the space in which the zealous ISIS has come to the fore. Where ISIS rules it is widely unpopular – in a country of smokers, Cockburn notes, they have demanded bonfires of cigarettes in captured towns – but too many of ISIS’s enemies are opposed to all Sunnis, not just ISIS. This means Sunnis opposed to ISIS have no one to turn to for protection or support. All too many have calculated that enforced piety and oppression from ISIS are preferable to being murdered by Shia militiamen in police uniforms just for being Sunni.

But one of the most influential factors in the rise of the Islamic State in Iraq has been events in neighbouring Syria. Shifting his aim westwards, Cockburn provides analysis of events that is both illuminating and frustrating. The interference of external powers in Syria, whether Middle-Eastern or Western, has had catastrophic and usually counter-productive effect. In the midst of a supposed ‘global war’ on Islamic terror, the logic of toppling yet another bastion of Ba’athist-style dictatorial secularism in the region is murky. Encouraging a Sunni uprising in Syria without foreseeing a knock-on effect in neighbouring Iraq also strikes Cockburn as particularly naive.

The vitality of continued opposition to Assad by the US-led Western powers and by states in the region is astonishing – almost satanic. The United States happily allied itself with the most murderous force in the twentieth century – the USSR – in order to defeat the more pressing evil of Nazi Germany. And yet the exponentially milder Assad regime is somehow considered totally untouchable – or ‘haram’ as the locals of the region might say. It was only twenty-odd years ago Syrian troops were fighting as part of the US-led coalition in the First Gulf War. The transformation since then is inexplicable (and, with his hands already full, Cockburn does not attempt to offer any insight into this).

Despite the severity of the civil war being waged in Syria, the West has demonstrated openly and brazenly that it is more interested in eliminating Assad than ending the war. As Cockburn frequently points out, Assad has continuously been in control of all but two regional capitals in Syria, yet the United States says he can’t even have a place at the negotiating table unless he agrees to give up power. That’s not a pre-condition: it’s a repudiation. Failed politicians in this part of the world don’t retire to bank boards and book deals like in the West – more often their bloodied corpses are dragged from their palaces by a mob of well-orchestrated ferocity. (The victors’ justice of Saddam’s execution is a rare example that tests the rule.)

Laying the Assad-must-go precondition is a bold statement by Western powers that they grant zero priority to ending the war. Despite all their high-minded liberal humanitarian cover talk, it’s simply not on the agenda: Power is the only thing.

Despite the unsurprisingly depressing subject matter, the author is persuasive in his clear and cogent writing. This book—and Cockburn’s reporting more generally—is helpful both to those with some familiarity with the region and total novices in deepening one’s understanding of a situation that defies adjectives.

As bombs were falling on Libya, Cockburn pointed out the jihadist nature of many of the rebel groups in the north African country, only to be confronted by an American reporter: “Just remember who the good guys are.” For those looking to avoid the Manichean oversimplifications we are too often fed, this book is a welcome and insightful reprieve.

Letter to the Editor: The Times

There has been a distinct increase in the number of missives sent out from Huis Cusack to editorial offices across Europe and beyond as part of my slow but inevitable transformation into “Disgruntled of Tunbridge Wells”. It all started with an extremely pedantic letter to the TLS regarding PG Wodehouse, banking, and the collapse of the rupee that was printed in October 2008.

It escaped my notice at the time but it turns out the editors of The Times of London were short of anything decent to print last November so stuck one of my letters in. Very kind of them.

Sir, There is a parallel to the situation of Britons involuntarily losing their EU citizenship: the unionists who fell on the southern side of the border when Ireland was partitioned in 1921. Like the British in Europe today, many Irish then felt themselves secondarily or primarily British or at least strongly associated with Great Britain, given the unitary state which had existed for more than a century. More Irish volunteered their service and their lives for the British crown than ever did for an Irish republic.

As an Irish citizen resident in the UK I appreciate the generosity of spirit whereby Ireland is not a “foreign” country. Irish in Britain today have full civil and political rights above and beyond those of other EU citizens, and this is reciprocated in the Republic (except for presidential elections and referendums).

Were the EU to extend such generosity and reciprocity to the UK after Brexit it would go a long way to furthering our common identity and friendship.

ANDREW CUSACK

London SW3

Of course I am as poblachtánach as anyone else — Up Dev and all that — but one does appreciate the difficulty of those Irish who also identified as British once the Free State was erected. But then given my background (Irish New Yorker educated there, in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa, resident in London) I don’t see any problem with a multiplicity of overlapping identities. All the same, when people imply they will somehow mystically cease to be European come 29 March it just makes them look silly. Great Britain has always been a European country and always will be.

I blame Ulster, the French Revolution, and the Fall of Man.

Neo-Classical New York

The dome of the old Police Headquarters Centre Street in New York.

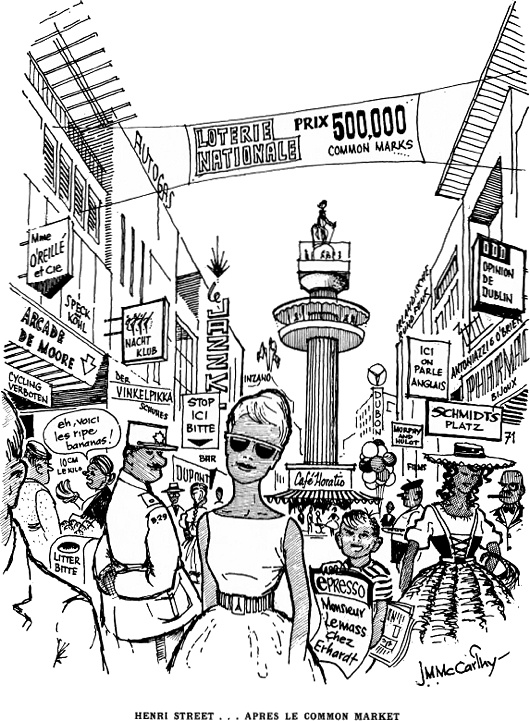

Dublin in the Common Market

A full decade before Ireland joined the E.E.C., cartoonist J.M. McCarthy filed this vision of the Irish capital’s cosmopolitan future in a 1962 issue of Dublin Opinion.

The scene is Henry Street — renamed “Henri” of course — leading up to Nelson’s Pillar in O’Connell Street and the wags show dear old dirty Dublin transformed into a polyglot European capital.

Advertisements and shop signs are in every language (except Irish), the Gardaí have adopted a képi as their headgear, the currency is the “common mark”, and a stylish young woman with bare arms steals the show and sets the tone.

The European Economic Community finally admitted Ireland as a member in 1973, by which time Nelson had be blown up and Dublin Opinion ceased publication.

Roots and Permanent Interests

Dolosse

dolos, pl. dolosse

Visitors to the seaside and frequenters of port cities will be familiar with those oddly shaped concrete forms which are dropped together to form breakwaters and prevent erosion.

It turns out that they have a name of Afrikaans origin: dolos (plural dolosse).

‘Dolos’ is believed to be a contraction of ‘dollen os’, the name for the children’s toy of knucklebones or jacks. This particular shape was invented by Aubrey Kruger and Eric Mowbray Merrifield to rebuild the revetments of East London’s artificial harbours following the great storm of 1963.

Kruger fashioned a smaller version of the shape to show his idea to Merrifield, and legend has it that Kruger’s father visited them on the quayside and asked Wat speel julle met die dolos? (‘What are you playing at with the jack?’) The name stuck.

In 2016 the South African Mint released a two-rand ‘crown’ coin depicting the dolos as a tribute to this example of South African ingenuity.

Around

“By contrast, Hungary’s 100,000 Jews—a larger presence relative to the country’s population of 8 million—walk unmolested to synagogue in traditional Jewish costume and hold street fairs with minimal security presence.” The Real Modern Anti-Semitism

No American writer has wielded such influence, John Rossi writes. So why is he so little known today? The Strange Death of H.L. Mencken

Damon Searl on Uwe Johnson: The Hardest Book I’ve Ever Translated.

Then there are the mythical and miraculous islands of the medieval Atlantic

120 years after the Spanish-American War, here are five books to help you better understand American imperialism.

The always-worth-reading Michael Brendan Dougherty explores what the Catholic traditionalists of the 1960s and 1970s were thinking. (More people, however, are talking about his look at Francis’s record as pope.)

In Manhattan, John Massengale suggests there are better ways to get around town.

Argentina’s most beloved bibliophile Alberto Manguel on the great books that are now lost to history.

In Hungary, like everywhere else, people are marrying later, with demographic consequences. Or is this changing? The country is not just experiencing a fertility spike, Lyman Stone reports. Hungary is winding back the clock on much of the fertility and family-structure transition that demographers have long considered inevitable. Is Hungary Experiencing a Policy-Induced Baby Boom?

Speaking of which, from the same author, what about Poland’s Baby Bump?

Meanwhile in New England, an entitled Harvard academic pulls rank on the mother and child living in an affordable unit in their apartment building in a telling tale of class and hierarchy in America.

Knickerbocker Spires

Before the age of the skyscrapers, New York’s church spires dominated the horizon and dwarfed their neighbours just like in the medieval towns and cities of the old world — as this photo from the 1900s shows.

Here St Patrick’s Cathedral holds court, with the St. Nicholas Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church poking up a few blocks down Fifth Avenue.

Slightly north on that same boulevard sits the grand renaissance palazzo of the University Club, with the spire of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church poking up behind it.

Ten Books

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Image: © HughJLF

Image: © HughJLF Image: © Stephen Benton

Image: © Stephen Benton Image: © Stephen Benton

Image: © Stephen Benton