Cusack’s Diary

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Into the Qadisha Valley

THE HOLY VALLEY cuts down like a gash in the earth, with the cathedral city of Bcharré on the clifftop, almost hanging off of it. One almost wonders if you started building at the other end of the town, it might force St Seba’s Cathedral off over into the deep beyond. There is something almost Lord of the Rings about the setting, a Levantine Minas Tirith, if only Tolkein had been a Maronite.

The Qadisha Valley (Ouadi Qadisha, وادي قاديشا, literally the “Holy Valley”) takes its name from the Aramaic word for saintly and for over a millennium its natural caves have provided shelter for hermits seeking solitude as well as others seeking refuge and safety. Evidence of human habitation dates back to the Paleolithic era, and the Qannubin Monastery here is said to have been founded by the Emperor Theodosius the Great in the fourth century. While this is the holiest ground of the Maronite Catholics, hermits living in these caves and in these monasteries have been Melchite, Nestorian, Armenian, Syrian Orthodox, and Ethiopian. When the Monastery of St Maron was sacked by Antiochene Monophysites, many monks fled to the Qadisha Valley, strengthening the presence of this Eastern church which has always remained in communion with Rome. For over five hundred years, the Maronite patriarch made Deir Qannubin his seat. (Since 1830 the Patriarchate has been based at Bkerké above the pleasant Mediterranean city of Jounieh). (more…)

Lebanon Diary

Early evening sun illuminates the pendentives and architraves of the Maronite church. Discoloured prints of numerous saints — of East and West — crowd one of the few side altars. The Arabic numerals indicate the date of its dedication: 1971 — before the war.

Without internet in a remote village in northern Lebanon, elevation 500 ft, we are cut off from the outside world. Word reaches us of a military coup in Egypt. (I hate missing a coup!) The reactions are a mixture of relief and caution, and a little wonderment at how things must have moved very quickly. Curiosity is sparked as to what else is going on in the world outside Sourat.

Dappled sunlight. Unfamiliar saints. A lizard scurries past, its long processional tail trailing behind it.

D.G. of the Financial Times drops in and brings that commodity we most desire: news from elsewhere. I quiz him on the coup in Egypt, how it played out, how it was orchestrated, and what he thinks of it, but there is little time.

At night, reading Ian Fleming’s From Russia With Love on the terrace with a Gauloise and a bottle of Almaza. Two wolves cry in the distance and I remember hearing the snorting of a wild boar a few nights previous. One chased Emmanuel on his way back from ‘the Palace’ (as we have dubbed the Abouna’s house, where the honoured guests stay) and was shot and killed — the photos of the quarry being displayed on an iPhone handed round.

The night is punctuated by the sound of repeated explosions in the distance. Luckily these are fireworks — a particular Lebanese obsession. It seems symptomatic of the Lebanese mentality that — having spent so long being so close to death — it is necessary to celebrate being alive. One may as well have a good time, and the Lebanese are experienced at having a good time.

In the car on the way to the pharmacy, Mahe our indispensable handyman (and a refugee) talks to Niall about Syria. “Syria. Big war. Boom boom. Muslims fight Assad. Assad fight Muslims. Big war.”

BUILD! BUILD! BUILD! Beirut is abuzz with cranes and construction and wood boarding over the site of new projects. That tower wasn’t there last year, was it? No. And doubtless by next year new spires will scrape the sky over St George’s Bay, where the saint slew the dragon. Is he dormant there beneath the waters still? Something lurks perpetually beneath the Lebanon, occasionally raising its head above the surface in open violence. Just then a Hezbollah building in the southern suburbs is bombed. The list of assassinations in this country’s history is long and depressing, from that of Maarouf Saad which (arguably) sparked the fifteen-year Civil War, and of course the former prime minister Rafik Hariri’s killing in 2005. Even since Hariri’s death, no fewer than twelve Lebanese public figures have been assassinated.

Have you ever been to Rafik Hariri’s tomb? It’s a slightly vulgar thing, still shrouded in its temporary marquee, giving it a somewhat transient feel, as if it might up sticks and away to Sidon or Tripoli at a moment’s notice. We nipped in the other day after a trip to the adjacent mosque he had built, completed in 2007 with its brilliant blue dome. The mosque’s design is traditional but not entirely perfect. The massive crystal chandelier hanging from the vast central dome is impressive but perhaps a bit much. Somehow, we are deprived of ancillary spaces: going through the main entrance one feels a certain lack of procession. No narthex, no nave, you just take off your shoes, step through the open doors, and are there. Why not one of those spacious courtyards which grace so many older mosques? Land in Beirut doesn’t come cheap.

Of course, when it was completed it was noticed that the minarets overshadowed the campanile of the adjacent Maronite cathedral, which meant the Catholic bell-tower had to be rebuilt to be at least the same height as the Sunni minaret, or perhaps an inch taller. Just to be on the safe side.

We had arranged to meet G. and the others twenty minutes later at the Grand Café on the Place de l’Étoile, which was a silly idea. A wedding was finishing at St George’s, the Greek cathedral, as we rolled up and we joined in the applause for the happy couple when they exeunted the church. In between, however, we nipped in to Hariri’s tomb, or perhaps shrine is the more appropriate word. It is choc-a-bloc with oversized portrait photographs of the smiling premier in his prime — a mix of political, semi-tribal, and religious devotion. The soldiers guard it nonchalantly and seem glad for some visitors on a Saturday afternoon. One presumes plans are being made for some grand mausoleum to supersed the transient tent with its faint hint of a vagabond yurt. We had to move on to a rather trendy place in Gemmayze, Mo stopping along the way as he ran into friends.

These nuns are magnificent: it is impossible to respect them enough. They do an impossible task taking care of so many physically and mentally handicapped, on very little resources. They take anyone and everyone under their wing — Christian, Muslim, Druze, whatever. Their founder, Abouna Yaacoub (Père Jacques), is up for canonisation and the fruits of his foundation are still flowering. We’ve visited a number of the care homes they run — in Antelias, Dar al Kamar, etc. — and while the conditions are very basic I think the love these nuns have shines through. They have devoted their entire lives to serve these men and women who often, ignored and forgotten, have no one else. They are also completely clued in; you wouldn’t be able to get anything past them. The Mother Superior’s mobile rings, she answers and buzzes off away to put something right.

Arabic is a beautiful language, though at its most beautiful when spoken by women. (But then: isn’t every language?)

“Our relationship to France is completely different. We were never a colony, only a protectorate, a mandate. My grandparents still refer to France as the mother country.” Still, the decline of the French language here is noticeable, as is the concurrent advance of English. The new global tongue dominates billboards and advertisements, not to mention the radio. In some places in the countryside, I’ve seen new streetsigns in Arabic first and English second: no French. (Beirut seems to have escaped this phenomenon).

If Lebanon ever loses the French language, it will lose part of itself. But the Lebanese, who have many admirable qualities, are expert businessmen — merchanting is in their blood — and English is the language of business. Not just business, but culture too: if you’re given a handbill advertising some small art show or exhibition, it’s invariably in English.

An evening party at a family home in Bsous, on the hills overlooking the capital. Everything is simply perfect. R, S, and I sit down amidst the grove of olive trees and immediately a small table with nibbly things is moved to just before us for our convenience. Beer, wine, and merriment flow and while the pool shines glows eerily as the lights of Beirut twinkle before us. Our hosts speak little English but we make do with French. P.A. claims (in that way that he often does) that P.’s father is so brilliant he was Minister of Finance to both Lebanese governments during the Civil War. When was this house built? 1890s? 1910s? It’s hard to tell. It suffered during the war but has been restored well and sensibly. Its location is beyond envy and I only wish we were here during the day to see the view across Beirut to the Mediterranean beyond.

Curiosity Killed the Cat

Or: our love/hate relationship with the Phoenix, Chelsea

It was an unusually warm evening for a night in March, which is to say that it was not horrendously cold and you could tarry a while outside without fear of frostbite. Given the nature of his job, Nicholas is not frequently free to socialise, as he has to be doing certain things in certain places at certain times, which sometimes involves being in Greece or a sudden trip to Anguilla (“I’m not doing any more Caribbean islands — I’m fucking tired of them.”). But when he does manage to free himself from indentured servitude, we often find ourselves at the Phoenix on Smith Street.

All sensible right-minded people love the Phoenix and hate the Phoenix. It is a wonderful place, comfortable and delightful, yet somehow attracts the very worst and most tiresome lot of humanity. “Look at these estate agents,” Nicholas moans in the put-on snobbery which has become one of his traits. “They all live in Fulham I’m sure.” (Which is rich, as I live even beyond Fulham). Kit and H. were dining there with Ivo & la B a week or two earlier (or later) and such was the tiresomeness of the crowd that Kit texted Ivo “What a bunch of overgrown yuppies” (or something along those lines).

It’s delightful during the day, and there was one afternoon not long ago when, sauntering down the King’s Road, I ran into Prof. Pink on his way to John Lewis and managed to waylay him into an enjoyable conversation at the Phoenix over two large glasses of the house white. But during the evening the crowd gets so horrendously up-itself that it almost becomes an attraction in itself. “It’s ten o’clock on a Friday night. Shall we drop in to Smith Street and see how awful everyone is?” The experience ends up infecting one with a reverse snobbery almost as snobbish and pretentious as the pretentious snobbery one is reacting against in the first place.

As I was saying, it was a warm evening and Nicholas managed to find an ideal parking spot within sight just round the corner on Woodfall Street. I think it was a Friday or a Saturday so naturally the place was packed inside and I’m partial to the occasional Dunhill so enjoying an exceptionally refreshing cider outdoors with a cigarette was the obvious way forward. I lit up and Nikolai — very generously, as I’m sure it was my round — went inside to brave the crowds in search of drink. Now the curious thing about the smoking ban is that it has turned previously insular cells of humanity — smokers, that is — into a sort-of fraternité universelle. People who have absolutely nothing in common but for being at the same drinking establishment now, for better or worse, through the medium of tobacco, enjoy a recognisable commonality which can frequently turn conversational.

A little Spanish man with a moustache had a party inside celebrating his birthday — 31st, I think — and he ventured outdoors for a smoke and somehow or other conversation was initiated. A pleasant enough fellow but his chat was unexceptional and was suddenly interrupted by the arrival by cab of two tall-ish and rather fashionable Azeri girls, who may have been friends of friends of his or may have had nothing to do with him at all. Being a chatty Spaniard (and perhaps a bit ambitious) he engaged them in conversation almost as soon as they alighted their cab.

After the innocuous pleasantries of introduction all round he eventually asked the Azeri duette, “So where do you girls live?” “Knightsbridge” they replied. “Ah, cool, I’m in Knightsbridge a lot,” our Spanish friend replied as Nicholas, turning away, launched upon a severe, disapproving rolling of the eyes. “Why?” I interjected, somewhat mischievously pricking the balloon of his pretentiousness. After all: what possible excuse could anyone who neither works nor lives there reasonably have for being in Knightsbridge a lot? He turned towards me and with an irritated smile said “My friend, you are too curious; you ask too many questions.”

The Azeri girls remained unconvinced of him, and the birthday boy, having finished his cigarette (which I think came from my pack), sheepishly returned inside where his presumed friends had doubtless continued the celebration of his birth in his brief absence.

But we still all love the Phoenix.

The Roman Corner

Friends are continually sending me postcards from Rome, such that they have gradually accumulated in a pile in my room. An English friend sent me one, and then an Irish friend saw it while visiting and, doubtless moved by the spirit of one-up-manship, sent one himself, whereupon the first friend sent another, to be followed by the most recent one (which arrived today) of the Chiesa di S. Agostino in the Campo Marzio. A miniature St Peter’s Basilica was recently added to the mix as well.

Vienna Views

My written views of the city you will have to wait for (presuming they ever see the light of day), but here are a few photographic impressions from my jaunt to the Kaiserliche Hauptstadt. (more…)

The Ever Useful Haggis

Culinary skills are not prominent among my varied talents, though I was pleased that the guests at the last dinner party I held in my riparian West London abode received the evening rather well. (If the food was only so-so at least the thought behind the choice and mixture of guests was appreciated). In my limited (but slowly expanding) experience, I have found haggis a rather useful addition to the repertoire.

T’other day I cooked a haggis for supper, alongside some chips and peas — an unjustly neglected vegetable I can’t help but feel. (Boring old botanists insist the pea is actually a fruit, but never you mind). Unfortunately I lacked a suitable gravy or sauce, so had to make do with ketchup and mayonnaise (plus a dash of HP).

But what to do with the leftover haggis the next day? I tried spreading it on oatcakes but that was far too dry — oatcakes must be reserved for pâté, it seems. So instead I crumbled bits of haggis into a pot of tomato sauce, dobbed it with oregano, some mixed herbs, sea salt, and freshly crushed peppercorns, and enjoyed a surprisingly delicious meal which I’ve decided must be christened linguine alla scozzese.

London Lately

From a Pimlico rooftop, Friday afternoon.

At lunch, Friday.

A Saturday Mass in St Wilfrid’s Chapel, the Oratory.

A surprisingly sunny afternoon, yesterday in Ennismore Gardens.

A Rainy Day in Winchester

IT WAS LATE summer, neither particularly warm nor cold, and a bit rainy. I hadn’t seen Nicholas in a while but he wasn’t particularly keen on travelling into London. “Why not meet in Winchester?” he suggested, and, never having been to England’s former capital, I thought it was a good idea. I popped on the tube to Waterloo, got on a train, and in no time at all was in the county town of Hampshire. It’s a humanely size town, admirably located, and most famous for its medieval cathedral.

The thieving Protestants, not content with stealing all the cathedrals we built throughout the width and breadth of the land, highten the insult by charging admission to these former shrines and places of worship. I had arranged to meet Nicholas in the Cathedral, though, and the blighters got a good £6.50 out of me. I had a good wander round, though.

These mortuary chests contain the remains of the Saxon royalty of the kingdom of Wessex and later England.

Norman architecture is woefully underappreciated, and might form a useful style to return to today given its relative simplicity. So much Norman architecture was destroyed and replaced by Gothic during later periods of medieval prosperity, but at Winchester the Norman transepts remain.

William of Waynflete, buried here, was a high-flyer in his day. He was, varyingly, Bishop of Winchester, Headmaster of Winchester College, Provost of Eton, Lord Chancellor of England, and founded Magdalen College, Oxford. Not a bad innings.

Richard Foxe chose a more macabre memorial, but enjoyed similar success in this world: he was Bishop of Exeter, then of Bath & Wells, then of Durham, and finally of Winchester. He was Lord Privy Seal and founded Corpus Christi College at Oxford. Foxe and Erasmus sometimes wrote to eachother, and his elaborate crozier is on display at the Ashmolean.

The tomb of Henry Cardinal Beaufort is my favourite memorial in the cathedral. Beaufort — a Plantagenet — was Dean of Wells, Chancellor of the University of Oxford, Bishop of Lincoln, Lord Chancellor of England, and finally Cardinal Bishop of Winchester. He was a sometime papal legate for Germany, Hungary, and Bohemia, and most famously presided over the trial of St Joan of Arc.

One of the walls was inscribed with graffiti.

The cathedral is also the final resting place for the earthly remains of Hampshire native Jane Austen, but nevermind that.

Tours of the College were available, but we decided to leave it for another visit, and went on a wander in the direction of the Hospital of St Cross.

The Hospital of St Cross and Almshouse of Noble Poverty is the oldest charitable institution in England and the largest medieval almshouse. The church could be a small cathedral in and of itself, but as we arrived an interment was taking place, so we thought it best that it, too, was left for another day.

A Bill Committee in the Commons

A Bill Committee meeting in one of the richly decorated committee rooms of the Palace of Westminster. The Minister is standing, rattling on in an explanatory defence of his government’s bill. Ostensibly these committees exist so that MPs can examine legislation in line-by-line detail and raise questions about whatever points or aspects they believe might cause problems if enacted.

“The question is that Clause 15 stands as part of the Bill.”

The Chairman, an MP of considerable experience, presides, assisted by a retinue of civil servants. He chews a pen and stokes his brow, frustrated by the boredom of the subject at hand. He is perhaps thinking of the weekend and the extreme unlikeliness that he will get down to the coast, and his sailboat, given the inclement weather.

A Scottish Member rises on a Point and the Minister yields the floor. Concerns are expressed about the precise meaning of Subclause 36 Paragraph C and insinuations made about potential costs. The Minister rises and suggests the Member’s criticism is excessively harsh. He then concedes he may have been imprecise in his explanation of the process involved in Subclause 36 Paragraph C.

The Doorkeeper, absurdly and arcanely attired in white tie, tails, and with the royal arms hanging from a gold chain round his neck, wears thick-rimmed glasses and leans back on a desk in a carefree fashion, blissfully paying little attention to the point the Hon. Gentleman has made in response to the proposed amendment.

“Just for the sake of clarity, we are not now talking about Amendment 13?”

“I have no intention of moving Amendment 13.”

“On a Point of Order then, Mr Chair, is it proper that the Member discuss Amendments 21 and 26 when he is not moving Amendment 13, which is the first Amendment to be considered?”

The Chairman corrects that it is perfectly alright for the Member to discuss whichever amendment he would like.

There are at least eleven civil servants in the room. One on the side hands a paper to another. He reads it and nods approvingly before passing it on to the civil servant next to the Chair. Another Member rises to discuss Amendment 54 Clause C.

“There’s an important role for an independent body to exercise scrutiny over this area and it would be wise for it to have a statutory basis.”

The entire proceedings are overshadowed by the continual sound of shuffling papers. One Member doodles on the day’s order-paper. A journalist leaves. The Member stops doodling and consults his iPhone. Then the Minister is grateful for that point. He is surprised but aware, since he was given this junior ministerial role, by the frequency with which this matter has arisen and has spoken before the relevant Select Committee.

Another Member’s face is illuminated by the glow of the iPad he is leaning over.

“Now before I become too Churchillian,” the Minister continues, “I think we’d better turn to the matter of the Amendments. Now the Honourable Member has, perhaps understandably, raised the point…”

A female Member smiles and shares a jest with one of her party colleagues. The Doorkeeper’s shift ends and he is replaced by one of his bearded confrères. The civil servant beside the Chairman folds a paper and stares unthinkingly into the distance.

“In respect for the Hon. Gentleman’s desire for continuing debate and discussion with the relevant authorities…”

“He hasn’t addressed my point about Subsection 2!”

The portly Doorkeeper moves with surprising adroitness in delivering a note from a Member to a civil servant across the room. The Minister’s PPS hands him a relevant paper. The Chairman smiles in response to one of the Minister’s light-hearted remarks.

“I’m sure the Minister will agree that this is not the beginning of the end but merely the end of the beginning.”

“If only!” a Member interjects.

It is 3:32pm. The MPs will be here for hours yet.

Ten Random Photos of 2012

In roughly chronological order

Such has been the massive exodus from Facebook that I am forced to return to my previous practice of sharing random photographs via this platform. I suppose it’s just as well, as it will assure relatives in other places that I am actually alive. Keen observers will note that there are, in fact, more than ten photos, but nevermind. Apologies for the lack of explanation and the occasional in-joke (that’s in-joke… with a ‘Y’).

Burns Supper, Fulham.

Reunion of Scottish University Students, outside the Brompton Oratory.

Me and Johnny at Lourdes.

Downtown Beirut.

Nightclub, Beirut.

Party chez Jabre in the Lebanese mountains.

Marian procession, Malta pilgrimage, Walsingham. (Photo: Stephanie Kalber)

Autumn Drinks afterparty (disaster!) & Chabrouh fundraiser the next night.

Anastasia’s birthday.

A midwinter night’s run-into on the KR.

Yuletide, the West Country (…with a ‘Y’).

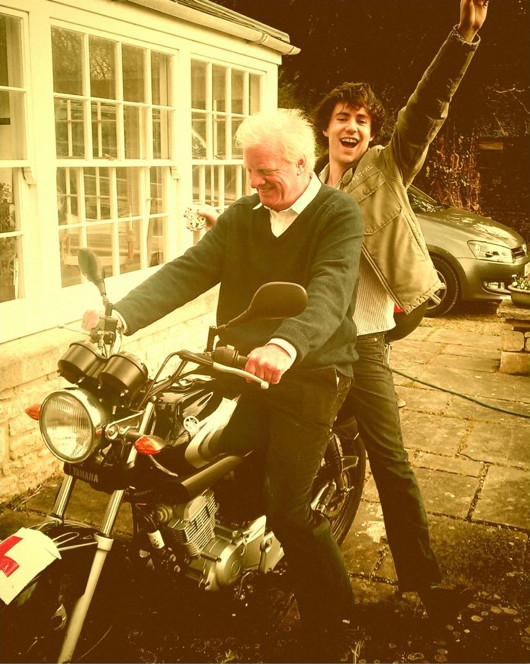

The Photo of 2012: Don Finiano convinces our favourite Member of Parliament to try out his new motorbike.

Tradtastic Hertfordshire

The bishops of England & Wales cunningly arranged for the Feast of the Epiphany to fall on the actual Epiphany this year. We had a great big festive lunch at our favourite little Italian place in South Ken, but the night before I went out to Hertfordshire, where I witnessed the tradition of a door being CMB’d with holy chalk for the new year (above).

Those unaware of this tradition can read a bit more here. The C+M+B stands both for Christus mansionem benedicat (“Christ bless this house”) and the names of the Three Magi: Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar.

The Lady in Red

Or: Where to sit in church on Sunday

IT IS A LOGICAL TRUISM that good habits are good. But good habits — well and fine as they are — can also produce ancillary habits that, while not ‘bad’, might perhaps also be worth denying the dignified title of ‘good’; they are ammoral rather than immoral. Hearing mass on Sunday is a good habit — indeed it is an obligatory good habit binding upon all the Faithful. Some people express their habit of Sunday mass at varying locations — an attitude which I find surprising, which itself is surprising given until very recently I varied my Sunday mass locale myself.

In New York, it was easy: there was only one real place to hear Mass and that was the Church of St Agnes on 43rd Street. Of course, some dangerous rapscallions dissented from this point de vue and attend the Church of Our Saviour on Park Avenue. I remember one Sunday on Lexington Avenue seeing the group of lads who serve the 11 o’clock mass at St Agnes come down the avenue while the like gang who did the same at the Church of Our Saviour were coming up it on the same side and it was like seeing the Sharks and the Jets meet in “West Side Story”.

In London, I used to go here and there; mostly dividing my Sundays between the Oratory and the Cathedral but every now and then sneaking in Holy Redeemer in Chelsea. But for a year or so, I have been an Oratory regular, and now look strangely upon those who, when the insouciant inquiry at a dinner party or over drinks or such is made “Where do you go to Mass?”, reply “Oh, you know, sometimes here, sometimes there, sometimes I even go to the local parish.” (I never believe the last assertation; I, for one, have only been to my local parish twice: once this past St Patrick’s Day to pray, in vain, for an Irish victory at Twickenham, and lastly on one of those lesser-remembered Holy Days of Obligation.)

But the ancillary (ammoral) habit to the (moral) habit of hearing mass on a Sunday is the custom of sitting in the same place. If one is new to a particular church, one can sit here and there for quite some time, but eventually you find a bit of the church and you realise one Sunday “Ah! This is just right!” and from that day forth you have “your” seat. The chaps who do the collection obviously must have their proper places. The one-legged lady in the wheelchair who shouts at people has her usual spot. A certain sturdy Knight of Malta enjoys sitting in more or less the same location every Sunday, and one friend of mine inexplicably likes sitting in the middle of the row towards the middle of the first section of seats beneath the dome. Inexplicable to me because I cannot abide having to climb over people to get to and fro at mass.

Anyhow, needless to say, I have my preferred seat at the Oratory on a Sunday. It is not even a neighbourhood of seats, or a small vicinity, it is a specific seat and I am loathe not to have it. This is because it is at the confluence of the various important factors. It is not so close to the front that you are mistaken for the religious fanatic, the overly pious, or Princess Michael of Kent. Yet it is not so far to the back that you have to walk a mile to receive Our Lord in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar come communion time. (And have you ever sat towards the back at the Oratory? Barely anyone says the responses! The Fathers should set up a specific mission towards the last twenty-odd pews at the 11:00 on a Sunday — I suspect they are unbaptised the lot of them).

Furthermore, there is a duality to the mode of seating at the Oratory: the first two sections, comprising about the first third of the church, are actual seats, whereas the last section is composed of hard, uncomfortable wooden pews. (Perhaps they don’t say the responses because they’re embittered by discomfort?). Also, I dislike being in between the pulpit and the sanctuary, thus necessitating that you have your back turned to the priest when time comes for him to preach. And I prefer to nip up to communion rather swiftly, so I can return and get all my prayers in and not spend half the time standing in a queue awkwardly awaiting the reception of the Eucharist. This, therefore, necessitates that I be directly on the aisle.

“My” seat — I will not reveal its specific location within the Oratory Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, Brompton, for the obvious reason of inviting competitors — “My” seat is thus located in precisely the perfect location. Needless to say, I’m used to the others who have found that “their” seat is adjacent or nearby (though I’m glad that one chap who objects to dogs being at mass has given up and gone elsewhere). I feel we all implictly know and understand each other without actually intercommunicating, in that way that researchers who frequent the same stacks in university libraries feel a certain affinity.

About a month ago, we received a new regular to our midst: a white-haired lady in what might be described as late middle age, hebdomidally clothed in a red overcoat. She began to take the seat next to mine. Very well. Pas de problème, etc. Then one Sunday, a slow-moving Italian family attending the previous mass were lingering in “our” row and both she and I assumed positions ready to take possession of our regular seats. Imagine my surprise, then, when the Lady in Red, in full knowledge of my presence, took my seat! Friends were in from the country that week and said they watched the entire scene in detached amusement from the other side of the church. Needless to say, I was reduced to taking the next seat over, usually the Lady in Red’s seat.

What did this fresh assault upon my dignity betoken? I knew not. But I was determined that, in the immortal words of an American president, this aggression would not stand. The next Sunday I made sure to arrive extra early and secure my seat succesfully but untriumphantly. (Triumphalism is a tiresome bore in others and a poor reflection upon one’s self). The Sunday following that she appeared in pole position to usurp my place yet again, but then she didn’t: she let me have it. This, of course, was really a back-handed triumphalism. Haha! See! I shall be the better Christian and let you have the seat to which you have been accustomed since time immemorial! Look ye mighty upon my works and despair!

“Very well!,” I thought, “two can play at this game!” I was determined the Sunday following to arrive early and to deferentially allow her to have the place to which I had grown to know and love so well. But, friends, the best-laid schemes of mice and men gang aft agley. This past Sunday I arrived a mere minute or two before mass was to start, and thus I was forced to sit in the north transept instead. What’s worse, the Lady in Red wasn’t even sitting in my seat: she had ceded it to a mantilla’d Filipino lady.

This raises a fresh quandary. If this past Sunday was “my” week to defer to her, but I failed, and she deferred to someone else, does that then mean that I must defer next week, and the rotation begins anew? Or do we stick to the previous rotation of her week / my week? I know not, but I must be off now, as my French flatmates are wailing, and I suspect there may be a mouse for me to kill. Abientot!

The Perfect Place for Coffee

I’m not sure when I became the sort of person who lounges around drinking coffee. I was never much of a fan of coffee, and remain deeply suspicious of it (hence, for example, refusing to become a daily coffee drinker — very dangerous!). I suppose it was on pilgrimage to Rome in my fourth year of university when I was introduced to the blessed simplicity of cappuccino e cornetto for breakfast; a total riposte to the traditional Scottish morning meals of my habit up ’til then.

After Rome, my daily habit became to rise around 9 o’clock, complete one’s morning toilette, head out around 10 to pick up Le Figaro and maybe The Scotsman if I was in the mood, and then a sugar doughring from Fisher & Donaldson, after which I would sit in Taste, the minuscule place on North St at the top of Murray Park which serves the best coffee in the Royal Burgh, for about an hour or so reading and staring out the window episodically while nursing a cappuccino. This was an exceptionally enjoyable routine, brought to an abrupt end by the cruel realities of the forward movement of time and finishing one’s degree.

Whether rightly or not, I’ve no idea, the concept of dwelling over coffee seems more a habit north of the Alps than south. The quick coffee seems more Italian, and more than once I stopped into Taste with Stefano or others for an unponderous espresso when an afternoon pick-me-up was deemed amenable.

But for the most part, I prefer to rest with a bit of coffee, and read something interesting. Last summer I found myself with a lot of free time in London and spent the greater portion of it in a curious little café-bar not open to the general public reading long historical articles off of JSTOR on such fascinating subjects as the origins of Argentine militarism or the unexpected nineteenth-century German Catholic revival as well as translations of the indispensable Pierre Manent printed in Modern Age.

There was barely ever anyone there in high summer except the two barstaff, myself, and a haggard journalist in late middle age sitting at the bar nursing his first pint of the day. I still go there from time to time, and recently enjoyed sitting there reading Perry Anderson’s trilogy of insightful, deep, and informative articles on India from the London Review of Books (‘Gandhi Centre Stage’, LRB 5 July 2012; ‘Why Partition?’, LRB 19 July 2012; ‘After Nehru’ LRB 2 August 2012).

There is a Pret near my flat where the staff are very nice, but I remember one Saturday morning when I actually stirred from my slumber and fancied catching up with the weekend Irish Independent. I happened to sit next to an awkward Indian computer engineer on a blind date with a Polish girl lacking in self-esteem. I found I could barely get any reading done with them nextdoor and instead relayed the essence of their conversation to a pretty girl sitting in bed in Oxford reading Glamour, who relayed back her own thoughts. The pros and cons of your average Pret come to mind and encourage me to explore what the perfect place for coffee would be like.

First, a coffee place should be mildly popular. There ought to be enough people milling around that it feels lived-in but not so many that you can rarely find a place to sit. The staff must be highly competent in their coffee making, and preferably either young, pretty, Italian, and female or else French chaps with a slightly haughty demeanour until the third or fourth time they see you. We will also accept vaguely hippie/alt-ish characters mostly from the Continent or occasionally the Antipodes. And Inez. (Inez, you can work at any coffee place approaching perfection).

Counter space! This cannot be emphasised enough: there ought to be counter space. I dislike when places have large, tall, bulky displays of the variety of pastries and such on offer and then have a tiny little open space to give your order and pay, etc. Broad counter spaces relay a certain openness and give the impression that the staff behind the bar are accessible. By all means display your delectamenta but you should aim for balance and harmony in your serving area.

There ought to be counter seating as well. Lots of coffee places put this at the window, which is acceptable, but as I like to sit in a large comfy chair and stare out the window, this is impeded by window counter seating, and thus I am mostly against it. And windows: we must have windows, preferably big giant ones with a single plane of glass looking out on a somewhat busy street, or even better a small public square.

Seating is one of the most important aspects. Hard or soft? High tables or low? In a word: both. There ought to be more café-style seats and round tables for when there’s three or four of you gathering, but also soft big comfy chairs for when that feels more appropriate. Different coffee-imbibing situations require different kinds of seating, and the perfect place for coffee should offer both.

I’ve yet to find the perfect place for coffee in London. I was quite fond of the Caffè Nero on Warwick Way in Pimlico with its huge glass panels that open up on summer days, but now that I no longer live in Pimlico it has ceased to be useful or easy to get to. As chains go, I tend to err on the side of Pret, perhaps merely out of habit. Whatever you do, just don’t go to Starbucks. Have some dignity and self-regard.

And if you do find the perfect place for coffee, do let the rest of us know.

A Mantelpiece

ONE MUST ALWAYS have a mantelpiece. That, at any rate, is my considered opinion. It is a focal point where one can place random objects of vague significance upon it as a salutary reminder of the varied importance of the numerous sectors of one’s life and the gentle interplay therebetween. In my admittedly brief (yet increasingly less brief) existence, I have had several mantelpieces. Indeed, I was even for a year at university in possession of a listed mantelpiece though, sadly, it was abused by the presence of an interloping non-functioning electric heater. But my current riparian London residence is augmented by a number of mantelpieces, one of which fortuitously sits in my own bedroom. While I generally prefer to leave things unexplained, here is a little guide to my mantel as it now stands.

Behind the entire tableaux hangs a French map of Africa I picked up during the summer I lived in Oxford. The recent independence of South Sudan renders it inaccurate, in addition to two or three vexillological changes in its corner display of flags. From left to right, we have the pennon of the Order of Malta in Scotland; the piece of the Berlin Wall my kindergarten teacher brought back from Germany for me; a Rackham postcard from Don Riccardo illustrating depicting a scene from Baron Foqué’s Undine (“Soon she was lost to sight in the Danube”), to which Don Riccardo has added the cryptic line “The fate, it seems, of all Cusack’s loves”.

Next is the glass flask with leather covering I picked up at an antiques place in Millbrook when wandering around hunt country with the Gills; a postcard of Bonnie Prince Charlie sent by the Cap’t as a thank-you note for hosting lunch at Rocca with our favourite ancient veteran of King’s African Rifles; the order of service from the University of St Andrews Alumni Club London carol service; a small bottle of Unicum brought back from Hungary by E.W.; a Marian prayer card from Tom & Alice; a little unpretentious triptych some relative bought; my Order of Malta Lourdes pilgrimage medal; an Infant of Prague retrieved from my grandparents’ house; a St Benedict medal (perhaps obtained at Downside).

The bottle of Boplaas Port was kindly (and perhaps unintentionally) left by one of the previous South African residents of our flat. It was finished off by our Continental correspondent Alexander Shaw and I late one night when he had just alighted the Eurostar and not yet had time to drop his bags off at his grandmother’s place a few minutes up the river on Chiswick Mall. Cornelius Bear is dressed in the red gown of a St Andrews undergraduate. Behind him is a Quebec automobile numberplate and a prayer card from St Philip’s Day 2012 at the Oratory. My Magister Artium diploma is rolled up in its tube next to an empty box of Dunhills purchased in Milan — “Il fumo invecchia la pelle” it warns. Surmounting all is a palm from Palm Sunday at the Oratory.

Milan Diary

I STEPPED OUT OF the airplane and the long line of the Alps smacked me in the face about the same time as the freshness of the Lombard air. One of the more boring innovations of today’s world are those mechanical arms that stick out of air terminals to usher you from hermetically sealed environment to hermetically sealed environment. (One of the reasons why Bristol Airport is among my favourites, besides being in Somerset, is the total lack of those loading arms.) Landing at Malpensa, I was pleased to step out onto the stairway with the sun behind my back illuminating the glorious string of snow-capped peaks in the far off distance — a reminder that Milan is indeed a different Italy from the hills of Rome or that Greek-speckled island of Sicily. The polizia di frontiera manning the Unione europea queue takes the barest glance at my maroon passport before handing it back with a forlorn grazie and waving me on my way with a nod of the head.

I made my to the train station, bought a ticket from the little machine — brushing aside a little taxi man with a dismissive no grazie — and boarded the treno diretto a Milano Cadorna. I had left behind a rather grey, miserable, and cold London just two hours before and as the Malpensa Express hurtled through tunnel, cut, and way, I’ll confess the tiniest swivel of excitement — augmented by the glorious sunshine — at the prospect of discovering Milan, a city with which I had no previous acquaintance.

Milan boasts one of the greatest railway stations of the world — Milano Centrale — but I was heading into the smaller and more convenient Cadorna station. Alighting the train HM phones and barrages me with information as I confusedly try to stick my ticket into the slot to let me through the barrier oblivious to the words coming at me through my telefonino. Victory — success — I’m through, and agree to phone HM later when I know what’s what.

Finn’s instructions had been to take the Metro to his, but confronted with the cloudless beauty of the sky I found the idea of scuttling about underground lacked any appeal. A walk would do me good. Following the gentle curve of the Foro Buonaparte under the shade of the graceful trees, I took my measure of the city. I hadn’t any idea what to expect, really, but am pleased with what I find. There are awkward post-war modern bits (American bomber crews were not unfamiliar with Milan) but for the most part the city’s architecture betrays a sturdy late-nineteenth-century confidence that’s been sensibly updated to keep with the best of today’s standards. What’s more, the population are a positive adornment to this city: snappily dressed men of business wait at pedestrian crossings while pretty girls on bicycles sail by. The motto of Dublin is the slightly scary ‘Happy is the city where the citizens obey’ — Milan’s might as well be ‘Happy is the city where the citizens dress well’.

I turned onto the via Dante, continued down the Orefici, and was there at the piazza del Duomo, just a stone’s throw from Don Finiano’s. Dropping my things off in the flat, Finn suggests an immediate walk around the middle of town. “Luckily you can see everything here in a short space of time,” he avers with the assurance of his short attention span.

And so around Milan under the blue sky. The Duomo: “It’s the heaviest building in the world!” Still? “Maybe, maybe not.” Through the Galleria, as civilised a shopping promenade as ever existed, to La Scala. “Have you ever been to the opera? Here, that is.” “YES, with the Pogg!” On to the Castle and through its bifurcating series of portals to the park on the other side as Finn explains his various options for after his eventual departure from Milan. Swinging around and down the via Dante again, I run into a shocked Signora Bubesi who had no idea I was going to be around. (HM, typically, told her nothing). I kiss her hello and tell her I’ll see her later on. (We met up the next morning to see ‘The Last Supper’).

A late lunch by the Colonne di San Lorenzo as I offload the latest news from London and receive information, counter-information, and pure speculation about mutual friends and those in the general circle of things.

The sun still shining, we made our way to the roof terrace atop Finn’s flat. It actually belongs to the genial neighbourhood fascist who has allowed Finn the free use of it and emblasoned it with a quote from Mussolini. He once enlisted Finn’s help in carrying to the ascensore a large and heavy bust of Il Duce. The lift is absolutely tiny and just barely held the two of them, Il Duce, and a confused old man heading for the dentist’s office on the first floor. (The dental staff, reassuringly, use the rear balcony next to Finn’s as their smoking area).

Several larges bottles of Nastro Azzurro are consumed before we head back down to the flat to continue with spritz. The glories of spritz! Appropriately it was Ivo who introduced me to the ambrosian concoction — “Mate, try this. You won’t regret it.” — and I’d had Ivo, Hubert, and Callum round for dinner just the Thursday before; a night that rather typically ended with half-remembered lyrics to Irish rebel songs.

I’ll just pour myself a little more spritz. Oh very well, a full glass, must make up for the ice after all. The genial neighbourhood fascist pops round (in a black shirt, of course) and says hello as we discuss the possibilities of what to do for the evening, the sun having set over the course of the spritz being consumed. The Pogg goes onto Skype and summer plans are discussed for after Finn and Nick’s great Rome-to-Somerset motorbike expedition. We prefer Malta but the Pogg objects and absurdly suggests Isola d’Elba instead. What?!? We’ll see. Wherever the axes of price, sun, and proximity to water converge is where we’ll end up.

And again through the streets to the rather swish place atop that department store on the Piazza Cinque Giornate. After a Moscow Mule and something to eat, a cigarette on the smoking balcony. Looking out towards the city’s western flank and the night sky above it, we gaze downwards and watch the trams sleekly gliding through the piazza before turning our glance towards the appartamenti around the piazza. A surprising number are strangely dark for this time of night and we infer they’ve been bought by dodgy types as tax dodges or money-laundering manoeuvres.

Eventually we end up by the Colonne di San Lorenzo again, crowded with giovani as well as the occasional sketchy foreigner offering to sell you drugs. No grazie. Somehow we find ourselves chatting away with a group of people into the night. Finn, who is fairly fluent from living here, is mistakenly impressed by my knowledge of Italian, which confuses me since — unlike Irish, French, or Afrikaans — I’ve never studied it. A weekend in Milan, however, is enough to convince me it’d be a worthwhile endeavour.

And, having whiled away in conversation, at some unknown hour the police arrive to gently encourage everyone along their way, and returning to the various places from whence we came, we dispersed into the night.

Diary

WHAT WOULD it be like being a reindeer herder in Lappland? The perpetual attraction of some mode of living other than that which is immediately at hand lurks somewhere in human nature, especially at one might be described as the points of transition in life. But then, when properly considered, life itself is one permanent transition period. Indeed, not just life, but perhaps all existence, as I am discovering in the Purgatorio. Having breakfast in Oxford the other day I was informed I should read the Divine Comedy, as Dante’s ideas about the natural order of the universe supposedly coincide with precisely with mine. A few days later, as the sun was shining and giving us a delicious foretaste of spring, I decided to walk across Green Park, up Duke of York Steps, and over to the Piccadilly Waterstones to pick up a copy and have been duly transfixed by it. I am totally ignorant of theology and philosophy, all of which goes completely over my head, but I phoned up Rob, who’s properly clever, and he averred that Dante’s conception of order is based on Aquinas, and Aquinas is absolutely correct, so apparently we’re all quite sound. (Which is a relief). (more…)

Christmas Diary

The Cast:

Me (Cusack, interloping friend of the family)

Garabanda (Tom, paterfamilias)

Alexander (Alexander)

The Turkey (Joseph)

Finn (Finnian)

Woogy (Callum)

Ming (materfamilias)

et alia

23 DECEMBER

It was the strange clicking sound emerging from the engine of the Renault Espace that started us off on our journey. We were off to pick up Piccolo Giuseppe from Heathrow, where he was returning from his school skiing trip to Jasper in Alberta, and from Heathrow to whisk him, and ourselves, off to the country for Christmas.

Alexander had, according to Garabanda, insisted on debating the meaning of the universe until 2:00am the night before upon returning from the Oratory Christmas Spectacular, with the excuse that, spending the next week or so in Somerset, someone had to drink the wine before it went bad. I suggested it was a legitimate cause, but Garabanda pointed out no like offer was made with regard to the eggs or milk.

Mildly perturbed by the clattering click, Garabanda nonetheless steeled himself and surged forth westwards towards the great flight-harbour of Heathrow. There we disembarked the auto, Alexander and I seeking early morning comfort in the form of cappuccinos while Garabanda searched for the bog. We stood there awkwardly at that point where Terminal 3 regurgitates its arriving passengers disapproving of the sad and haggardly appearance of the frightful arrivées emerging from the sliding doors.

“I have to say,” asserted Alexander, with the slight diffidence earned by being an elder brother who attended a much more minor public school, “you can always tell the Etonians, so we just need to look out for when they start appearing and then we’ll find Joseph“. And sure enough, there was the Turkey himself. We went and exchanged the usual pleasantries of inquisition — How was Canada? What was the snow like? Did you sleep on the flight? — before wondering where on earth Pater Reverendissime was. Then we found Garabanda, one eye on his Morning Office, the other earnestly scanning the arriving folk, clearly unawares that his youngest had already passed through.

Back on the road. Where are the cupholders in this thing? We hadn’t finished our cappuccinos. What films were on the flight? Was Canadian skiing better than skiing on the Continent? Why on earth didn’t you sleep at all on the flight? What timezone are you in mentally now? Is that clicking sound getting worse?

Garabanda’s concern increases. More money than is perhaps ideal has already been invested into the maintenance of the Renault. Resolute though the Garabanda is, one could sense the irritation tinged with regret involved in his very practical choice of motor vehicle.

Reading Services. Perhaps we’d better stop and get this looked into. A phonecall to the Automobile Association. We’ll send a man round. I whip out the Irish Times (the previous day’s, I’m afraid) and grow increasingly concerned about the deleterious effect the new property tax will have on The Old Country. We keep our eyes peeled for the yellow AA van, and one duly arrives but the Garabanda goes forth to meet it and discovers it is not the one for us. Conversation probed the depths of the current situation in Europe before the right yellow AA van arrived. The nice man peeked under the bonnet, the engine was run, the sound was observed, and we were solemnly advised not to continue the onward journey to Somerset. A flatbed would be sent to pick up both the Renault and ourselves. It could be an hour and a half before he arrives, but he’d phone 15 minutes before to alert us.

“You know, I have to say, this is just typical. You buy French, you get French.” Alexander, it’s worth pointing out, does work for the Eurosceptic party in Brussels. The Turkey flapped his wings about gobbled a bit. Garabanda continued with his Office. Eventually the Boys decided to make an attempt on the conveniences provided, chiefly WH Smith and Burger King. Alexander searched in vain for the Economist, so he bought a harmonica instead (plus Scientific American). Joseph and I went for the Burger King option. And four crowns please. We all sat silently in the belly of the Renault, wearing our paper crowns as the rain gently pattered on the suitably inspected and bureaucrat approved shatterproof glass.

Eventually the flatbed found us and we found the flatbed. The Renault was moved onto its new perch and we all climbed into the surprisingly spacious cabin of the flatbed. A very rainy and peaceful journey on to Somerset continued, and I think all three of us lads in the back caught a bit of shuteye or two, though Alexander at least feigned reading his scientific magazine.

Closer to the destination, we were alerted to the updated plan of battled: Finnian would meet us at the lay-by just past the end of the lane and carry us on to the Farm, while Papa und Driver et Renault would head onwards to the Renault garage in Bath. As we approached, we sighted Finnian in the drizzle waving a property-for-sale sign up and down mechanically to catch our attention. The Garabanda gave orders to alight the flatbed and we duly alighted the flatbed.

Finnian’s car is decorated with silver tinsel in the festive spirit of the season. “Finnian, did the Pogg do this?” “Mate, the Pogg isn’t even around! Aw the Pogg, so Podgey-Pog, the Pogg!” Martina (pronounced podge) doesn’t like being called the Pogg because she finds it dismissive, but it’s quite obviously a term of endearment, and besides, it requires an article, which denotes her importance. The Pogg is the Pogg.

Swiftly through those country lanes — I had forgotten how fast Finn drives — around this bend and that and then with surprising speed we find ourselves at the Farm. Alexander and I hop out of Finn’s car as the Ming rushes out: Joseph has an orthodontist’s appointment in Bristol that must be kept. Inside the house, Callum calmly appears in the kitchen to bid us welcome in his fashion.

We sit around drinking a pot of rooibos inexplicably brewed in a French press and so tasting slightly of coffee. We hear a car purring up the gravel drive and sure enough it’s Ivo. Banter.

CHRISTMAS EVE

Porridge for breakfast. My love of proper porridge is such that I’m certain there must be a Scottish peasant or two in my ancestry. This morning’s porridge is taken with weapons-grade Iranian honey. How it ended up in Somerset, I’ve no idea.

Expedition to Bath. Alexander off for a haircut, Finn to seek some parfum for the Pogg. I potter about the architecture section of Waterstone’s with Callum, looking at big picture books of Edwardian houses. Eventually we all reunite and head to the nifty little café with pretty girls behind the counter, but its too crowded so we foolishly sit outside in the cold with our ciders.

The evening: a drinks party in the new wing of the Museum. We enjoy a fair amount of champagne and keep our eye on the Turkey to make sure he doesn’t overdo it. Banda whips out his sketchbook and takes down a face or two. Popping outside for the cool fresh air of winter, we are surrounding by a bizarre artistic installation of flowing fiberoptic lights in changing colours. When the moment comes, the party dissembles with surprising swiftness, and we return home for dinner.

Ming, Garabanda, and Woogy head off for Midnight Mass at St. John’s in Bath, but the rest of us are die-hards for Downside. We arrived around 11:20 with the abbey church mostly unfull. Alexander grabs his own seat to be alone with this thoughts while Finn, Joseph, and I grab three seats halfway down the still unfinished nave. The Turkey grins and whips out a flask… of orange juice. I nip over to St. Oliver’s shrine to get a prayer in.

Ivo arrives with father in tow and Hubert too. Says the women of the family abandoned them and opted for the following morning instead. Rupert and fam also in evidence a few rows behind us. Lord Hylton with his great big beard! He looks like Professor Alembeck from King Ottokar’s Sceptre.

A few carols before midnight, then finally the Mass itself begins. The Abbot processes down the nave in his finery, but looks a bit weary. Poor man: he hasn’t had an easy time of it. The church is glorious though, and glowing. Strange how it feels so like home returning to it. I didn’t even go to school here!

After Mass, see Dom Philip Jebb, still going, and surrounded by those paying him their respects. Then to the lower ref for some hot chocolate. Banter amongst the lads. Chat with Hubert about Irish republicanism. Gives me the name of a book to read. Hubert and Papa McG head home but Ivo decides to get a ride from us so he can stay longer. At Easter we went for a proper wander and Ivo regaled us with fond tales of naughtiness from school days.

We’re the last to leave as a monk urges us homewards. Apologies, apologies. Absolutely dark outside the looming abbey church as we make our way to Finn’s car. Alexander says we’re like German peasants departing midnight mass in times medieval. Ein extra potato to celebrate the feast he suggests, and a lemon curl on the fire to bring at least a bit of festivity to our grim, miserable lives.

CHRISTMAS DAY

The ancient former housekeeper arrives and tea is served beside the fire. Finnian always interrupting with questions and rude points. She turns to him and in her peaceful, elderly tone says “You always were the worst one!” Finnian is pleased as punch by her remark.

Having filled up at breakfast, we enjoy a simple brunch before Joseph and Finn are dispatched to steal mistletoe off a tree in the neighbouring farmer’s field. After surviving a barrage of rotten apples, I join them, and then Alexander and I go on a little journey up the hill and down further east and then back home along the lane.

After some time sitting around, Hein joins us and we go for another expedition: Ming, Garabanda, Callum, Finn, myself, Joseph, and Hein. Up the hill, looking out over the valley, and discussing various plans.

Back at the Farm we enjoy the most delicious foie gras in the universe — the fruit of Hein’s own labours — consumed joyfully along with a number of bottles of champagne.

Christmas dinner: the succulent turkey, fully stuffed, the sausages and bread pudding, carrots and brussel sprouts, and all manner of deliciousness on hand. The conversation excellent as always, with periodic bouts of violence breaking out in Joseph’s neighbourhood, likely instigated by Finnian.

Hein had brought along another creation: a Russian cake made with some sort of crackling ingredient that made such a noise and danced around on your tongue when you consumed it. Theatrical and tasty. In tribute, we listened to the Red Army Chir singing the Song of the Volga Boatmen, and then Garabanda suggested Glenn Miller’s version, which was enjoyed as well as the homemade elderberry gin was passed around.

BOXING DAY

Awoke to the sound of guns. Boxing Day shoots about the valley. Porridge for breakfast, and for lunch cockaleekie soup followed by cold turkey and stuffing.

We knew the McG’s were scheduled to come round at 4:00, but Finnian whimsied an impromptu trip into town to ‘hang a Pret’, so Joseph and I joined. Ming tired to stop us, saying the McG’s would be arriving at 3:00-3:30 but we spied what seemed an obvious subterfuge. In town, Giuseppe was sent out as footman to fetch three cappas while Finn and I waited in the car. Then we sent him to Starbucks so as to launch a scientific inquiry into the respective qualities of Pret cappuccino versus Starbucks cappuccino.

We were back at 3:12 and sure enough Clan McG arrived in two sorties starting at 3:31. (In the intervening period Finn had tied string to the empty paper cup that had contained his cappuccino and hung it from the Christmas tree — thus giving literal truth to his expression ‘hang a Pret’). Hubert, Ivo, Papa McG, and I discuss Scottish and Irish politics, and history, and de Valera, and the War, and the general scheme of things. Had a chat with Christabel about Roger Scruton’s Modern Culture and she persuades me to read it again even though she finds it “too right-wing and conservative”. (Bloody art school’s gotten to her).

Finn and Ming off to Dorset for the evening. Alexander, Callum, Joseph, Tom, and myself settled by the fire and watched Istvan Szabo’s film “Sunshine”. Could be vastly improved with a bit of editing, but for such an ambitious project it works better than one would expect. Midway through we broke out the Zwack Unicum and sipped it through the remainder of the film.

A simple supper followed by a quiet evening. A bit of piano from Tom, then Callum. Alexander retired early following a vain search for his book on nationalism in Silesia. I suggested he read the biography of Hansel Pless. Fr Rupert gave me a copy when I was on my way to South Africa but, much to my disapproval, it was lost by the South African Post Office en route to New York. Luckily I had finished reading it during one of the more grey weeks of winter in the Cape.

Retired myself to pack my bags, as I had to catch the morning train back home to London.

Jolly time. Christus est natus.

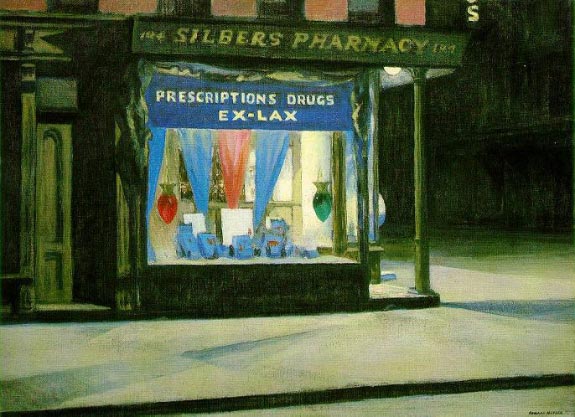

The American Drugstore

by Julián Marías

I REMEMBER MY ARRIVAL in Salt Lake City on a long shining train which had just crossed the endless plains of Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, and now had entered the land of the Mormons. When I got off the train and began to walk down the long avenue, now slick with ice, which stretches from the station to the Mormon Temple, I asked myself what I had lost in Utah, in this place where I didn’t even know the name of a single person. Undoubtedly the blame was this time – as in so many other cases – Jules Verne’s. Do you remember his Around the World in Eighty Days? Phineas Fogg, the phlegmatic gentleman, and his roguish servant Passepartout; in their company I came to know Utah and its Mormons for the first time, in my early youth. But let’s not deceive ourselves: youth somehow remains with us; I had a date with Salt Lake City from the age of ten, and now I was keeping it, walking slowly through the snow along a deserted street, toward the Mormon Temple, which glowed in the distance, and which can only be entered by the faithful.

This enormous temple, brightly lighted, seemed to orient and give meaning to the city. Very close by, the mountains, which surround the city and are visible on all sides, creating in its midst the image of a wild West. Frozen and almost deserted streets. And suddenly, the drugstore! There, in Salt Lake City, I finally understood its meaning. Always open, day and night, in any weather, brilliantly lit up like a beacon in the middle of the night, sheltering and hospitable like a port, full of things … like a drugstore, for in no other place are there so many things. Twenty-five-cent books on revolving wire stands; children’s records; magazines and newspaper; cigarettes, cameras, candies, luggage, electrical appliances, chairs, pens, toys, glasses, perfumes, stationery fishing tackle … anything you can think of. Since it has everything, there are even drugs and prescriptions in the American drugstore. And there is, strangely enough, a large counter, lined with plastic-covered stools, where one can order, at any hour of the day or night, and for a few cents, a couple of eggs, a cup of coffee, a milk shake, a hamburger, or what they call, with wonderful inventiveness, a cheeseburger. (more…)

Dublin Diary

WE START OUT at the usual Italian place, PH’s stammtisch despite his complaints that they’re stingy and never bring you a limoncello at the end of a meal, as is custom elsewhere. The usual verbal briefings are exchanged, updating each other on the scheme of things and the general banter. It’s warm enough to sit outside, which allows us the luxury of a cigarette with our coffee as we cast aspersions on passing strangers. This quickly moves on to casting aspersions on mutual acquaintances (we will not call them friends!) and extrapolating therefrom more general condemnations of the heresiarchs and heretics of our day (chiefly: liberals, Modernist clergy, fops, les Brideshead affectés, users of inappropriate typefaces, and all people who take life too seriously).

After the postprandial coffee, we head on to Doyle’s but, just as we arrive, Brian gets in touch directing us elsewhere. We meet up with him and his three friends on the street but PH and I do not take a shine to Brian’s temporary entourage and secede from the party. Where to? Lincoln’s Inn, end of Nassau Street. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories