Church

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

How to Make a Pope

Argentina is a strange place partly because it is simultaneously so familiar and yet completely different.

It is a world of its own but with deep echoes of the world outside; like someone you instantly recognise as a cousin even though you’re meeting them for the first time.

The world’s most famous Argentine died this week which provoked me to ponder about the country and time that formed him.

From the age of 10 until he was 19, young Jorge Mario Bergoglio lived in Perón’s Argentina.

■ Over at my Substack I wrote a little bit about the early life of the late Pope Francis and his Argentine upbringing. Read it here.

Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands

Monsignor Daniel Spraggon, Apostolic Prefect in Stanley

The anniversary of the Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands is a time to recall one of the archipelago’s most faithful shepherds: Monsignor Daniel Spraggon, the apostolic prefect of the Falklands, South Georgia, and South Sandwich Islands.

Born in Newcastle in 1912, Daniel’s parents died during his childhood, leaving him to be raised by Daniel and Kitty Anderson who taught him the skills of the butcher’s trade. At the age of 22, Daniel joined the Mill Hill Missionaries and studied throughout the Second World War, finally being ordained on the feast of Sts Peter & Paul in 1945.

The Mill Hill Fathers assigned him to Buea in the British Cameroons (today a component of the Anglophone part of Cameroun) where, in addition to caring for souls, he also raised pigs. Having impressed the local colonial officials, they successfully requested the Mill Hill Fathers assign Spraggon as a military chaplain to the Gold Coast Regiment of the Royal West African Field Force.

When the Gold Coast became the first of Britain’s West African colonies to achieve independence in 1957, Spraggon was retired with the rank of Major and honoured with an MBE. He maintained close and friendly contacts with several Ghanaian Army officers — “good men” in his words — some of whom were later involved in the overthrow of Ghana’s chaotic dictator Kwame Nkrumah in 1966.

To the South Atlantic

After years attending to mission appeals in Great Britain and North America, Father Spraggon was appointed to the Falklands in 1971 with the right of succession to the apostolic prefect Msgr James Ireland, who stood down in 1973. While still only a priest, Msgr Spraggon had all the authority of an ordinary bishop over the Falklands, South Georgia, the South Sandwich Islands, and the British Antarctic Territory.

Spraggon took to his task with vigour, encouraging the farmers to allow their children and farm workers to be educated, particularly when it came to matters of religion. As the Dictionary of Falklands Biography notes:

“Hospital visiting was a daily event even on a Sunday — not only were Catholic families visited but those of other denominations. This also held good on the ecumenical side. Many joint services were conducted in a warm and friendly spirit, though when he had to be firm he was.”

Pigs had been his department in Africa, but in the Falklands Msgr Spraggon turned instead to cattle. As the DFB relates:

“His cutting up of a quarter or half was a joy to behold — and his handling of the carcass showed a robust frame but belied a none too healthy body which he managed to hide so well. Sausages, brawn and soups were also his forte.”

The Argentine airline LADE began regular flights to Port Stanley in 1972, which brought Msgr Spraggon into contact with their officers and staff, by numbers overwhelmingly Catholic in religion.

In conversation, the Monsignor very frankly relayed to the LADE officials that the Islands were British, the Islanders were British, and that they would do everything in their power to remain British while also hoping to be as friendly as possible to their Argentine neighbours.

Invasion

The quiet pastoral life of the Falklands was rudely interrupted on 2 April 1982 when an overwhelming Argentine force invaded and seized the British territory.

The Argentine forces took the capital Port Stanley where the governor of the Falklands, Rex Masterman Hunt CMG, ordered them to depart the islands immediately and return to Argentina. The next day it was announced the invading occupiers were going to remove the Governor from the Falklands, flying him to Argentina where he could then return to London.

Hunt decided to don his full civil uniform — feathery cap and all — and march down the street to reassure islanders that Britain would be back. Spraggon, long since become a good friend to the administrator, ran up to take hold of him to bid farewell — for now.

“The Islanders will need you now more than ever, Monsignor,” Hunt told him. “I know you’ll do your best from them.” Spraggon embraced the Governor: “And I know you’ll be back.”

Sir Rex wrote later in his memoirs that Spraggon “universally liked and respected… was to prove a tower of strength during the occupation”.

Seeing Hunt in his full uniform, the cleric determined there and then that he would wear his full monsignor’s kit for the duration of the occupation — however long it lasted — to keep the Islanders hopes alive.

As prefect apostolic, Msgr Spraggon was not just a clergyman but the representative of the Holy See — a sovereign state in international law — on the Islands.

In his first interaction with the Argentine commanders, Msgr Spraggon echoed the Governor’s advice that they should leave the Falklands immediately, otherwise everyone “even the penguins” would depart.

As it happened, the Monsignor did everything in his power to make sure the Falklanders stayed put and were looked after. He crisscrossed the islands calling in on farmers and families, talking to islanders and calming them with his reassuring presence — again, in his full garb as prelate.

Dealing with the “Argies”

The Argentine military-civilian liaison officer on the island was a Commodore Carlos Bloomer-Reeve — an acquaintance of the Monsignor’s from the Argentine’s previous role with LADE airlines — assisted by Argentine naval captain (later vice admiral) Barry Melbourne Hussey. Spraggon and Bloomer-Reeve’s pre-existing relationship proved useful across the Argentine occupation as the Monsignor often had to advocate on behalf of individual islanders.

The only policeman on the island, PC Anton Livermore, initially tried to make do after the invasion in helping keep some civil order and preventing harm. Major Dowling of the Argentine Army was made the head of civil policing but when Dowling ordered Livermore to arrest a civilian, the constable refused. “They didn’t like that and threatened me, but Monsignor Spraggon sorted that out,” Livermore said. “I have a lot to thank Monsignor for.”

The invading forces were an odd lot. Most — not all — the Argentine officers had a decent reputation for gentlemanly conduct with the Islanders but they often showed an utter contempt for their own enlisted men. In contrast to the well-fed officers, the drafted Argentine enlistees were poorly nourished and sometimes begged or stole food from islanders.

“After the curfew they shot at anything that moved,” Spraggon reported. “They didn’t know one end of the gun from the other.” One evening a nervous conscript opened fire on the Monsignor’s house. Spraggon marched down to Comodoro Bloomer-Reeves’ office first thing the next morning and forced him to come and count the twenty-seven bullet holes in the priest’s house.

Two bullets had breached the lavatory at a potentially lethal angle. “Look at that!” he shouted at the Argentine with his thick Geordie accent. “If I’d been answering the call of nature, you’d now be answering to God!” Years later Spraggon showed Rex Hunt his thick copy of Moral and Pastoral Theology (Volume V) which a bullet had torn through: “They got through it quicker than I did!”

Throughout the occupation, the Monsignor never lost his confidence in an eventual British victory. He sensed that — once the British naval task force had been assembled — the Argentines on the island also suspected they would lose.

Mass continued to be offered in the Catholic church to mixed congregations of Islanders and occupiers. The Sunday following the Queen’s Birthday included a particularly lusty rendition of God Save the Queen, to the sheepish embarrassment of the Argentines.

Liberation and Life

When it came, the day of liberation was a source of great joy. The Islands’ old governor — and the Monsignor’s good friend — Sir Rex Hunt was flown back in triumph.

In his memoirs he recalls returning to Stanley:

“The two victorious commanders, Sandy Woodward and Jeremy Moore, welcomed me back but, before I could take the General Salute, I was engulfed by the crowd. Normally not renowned for displaying emotions, even the miserable weather couldn’t dampen their spirits. In that sea of faces I saw Syd and Betty Miller, crying this time from joy, not sorrow, and Monsignor Spraggon, in all his finery still and beaming goodwill and happiness.”

The Governor and the Prelate — Rex and Daniel — both stayed on in their roles following the liberation. There were many dead bodies scattered across the islands to deal with, and the Argentine government at that time refused to repatriate their own war dead.

The Falklands authorities decided to dedicate a plot of land for the enemy dead, consecrated by Monsignor Spraggon — saddened that so many lives had been lost so uselessly. “We looked after the poor buggers a lot better dead than their officers did alive,” he said.

For his efforts during the occupation, Monsignor Spraggon was awarded an OBE which he travelled to Buckingham Palace to receive in 1983.

The priest was no longer young, and the bad luck of an aneurysm saw him detained in the Islands’ King Edward Memorial Hospital on the fateful evening in April 1984 that a serious fire erupted.

With such a small population, in Stanley a fire is a matter of all-hands-on-deck — even the Governor. Again Sir Rex Hunt’s memoirs relay the scene:

When I got back to the west entrance, someone said that all the patients were out of the hospital and safely accounted for, but over in the nurses’ block they told me that this was not so – Monsignor was still inside, and Teresa and her baby, and perhaps others.

I dashed back to the west entrance and tried to make my way through the smoke to Monsignor’s room, but after a few yards I was coughing and spluttering and realised that, without breathing apparatus, it was hopeless. I returned to the door and waited anxiously, feeling utterly frustrated and helpless.

Suddenly figures emerged from the smoke wearing breathing apparatus and carrying a body. ‘It’s Barbara Chick’, said one, in a voice which I recognised as Marvin’s. ‘She’s dead, but there are more in there.’ They put her down in the entrance and went back into the smoke.

I tried to lift her, but she was too heavy for me. Helping hands appeared and we managed to lay her to one side of the main entrance. Apart from a blackened face, she was unharmed and indeed looked quite serene.

Out of the gloom for the second time loomed three figures, carrying another body. ‘It’s the Monsignor’, said Marvin, ‘He’s still alive.’ Four of us took him from the firemen and, as we did so, he groaned. It was music to my ears.

As we carried him across to the nurses’ quarters, his pyjama trousers slipped and I found myself holding him by one leg and a bare bottom. Alison was in the nurses’ quarters and quickly put him on oxygen. His face was absolutely black, but he was breathing.

As the life-giving oxygen filled his lungs, his eyes opened and he recognised me through the oxygen mask. Kneeling beside him, I said ‘Well, Daniel, I never thought I’d hold a Monsignor by the right buttock!’ His eyes twinkled and I knew that he was going to be all right.

Hunt had feared the Islands would lose their beloved Monsignor, but he was still going strong later that year.

On the evening of Christmas Day 1984, Hunt had Spraggon round for a glass, sitting by the peat fire in the small drawing room of Government House.

They discussed how long they might each continue in post. “I want to stay until you go,” the Prelate told the Governor, “and then I’ll go”.

The End

Spraggon made it to his friend’s final convening of the Executive Council of the colony in September 1985. He promised to see the Governor off before he left the Islands for good, scheduled for some weeks time.

Ten days later, the Governor returned to his office following his normal weekly briefing with HQ British Forces Falkland Islands when Father Monaghan, the Monsignor’s assistant, arrived “so overwrought that he could barely speak”.

Monsignor Spraggon had suffered a burst aorta and died just minutes earlier.

The Governor’s wife took Father Monaghan through to the drawing room while Sir Rex used the new satellite telephone link to ring through to the headquarters of the Mill Hill Fathers in London.

“I got through to the Superior General, Bishop de Wit, immediately,” Hunt wrote. “He promised to tell Daniel’s family and without a moment’s hesitation said that he would come down for the funeral. He caught the first available aircraft and arrived in my office with Daniel’s nephew, Edward Spraggon, six days later.”

On 3 October 1985, the six-foot-seven-inch-tall Dutch bishop presided at the funeral, speaking good English “in a deep resonant voice that seemed to come all the way up from his boots”.

Staying at the bullet-ridden priest’s house and looking out onto the ships in the harbour, the bishop spotted the name of HMS Endurance and chose this as the theme of his funeral oration, reflecting on this characteristic of the Monsignor’s life.

The Governor and the Bishop escorted Sproggan from the church to his final resting place in Stanley’s cemetery, where Sir Rex Hunt bid his friend farewell for the final time.

“For once the wind was not blowing on that bleak hillside,” Hunt reported, “and all was calm and serene.”

Monsignor Daniel Martin Spraggon MHM — requiescat in pace.

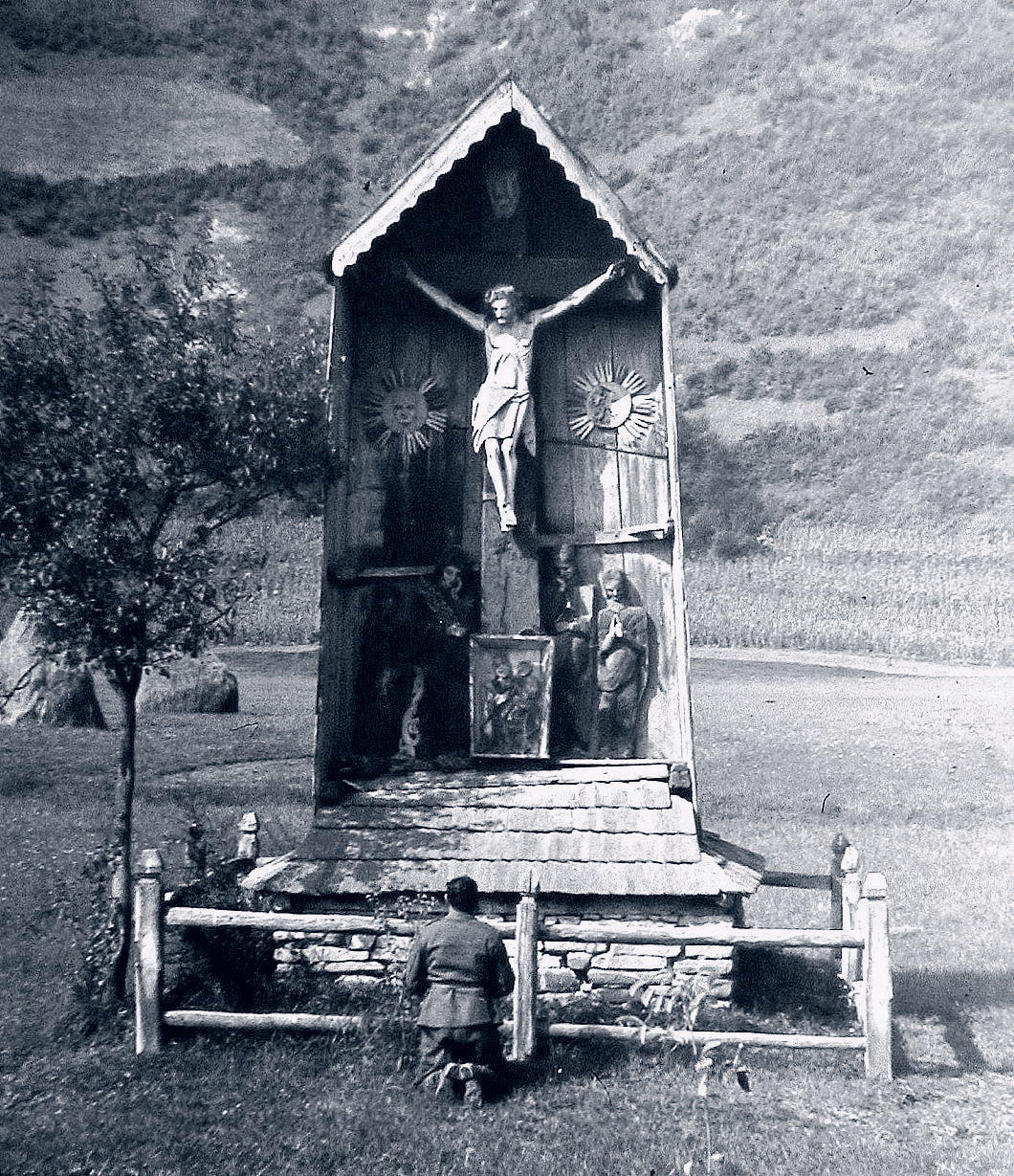

In thanksgiving for the lives and struggles of all clerics who have faithfully guided and guarded their flocks in difficult circumstances throughout the centuries.

Crux Alba Journal Launch

You are cordially invited to the launch of

This new journal is devoted to

the history and activities of the Order of Malta.

Please join us for a drink to celebrate the launch of this venture.

6:30pm to 9:00pm

Tuesday 18 February 2025

St Wilfrid’s Hall, Brompton Oratory, Brompton Road, London SW7 2RP

Copies will be available for purchase at £14

Please RSVP by 14 February to:

journal@gpesmom.org

Please share this invitation with others who might be interested in attending.

See also the Crux Alba website, Instagram, and Twitter.

Make Merry in thy Festival

I nipped over to Civitas in Tufton Street yesterday for the launch of Esmé Partridge’s report Restoring the Value of Parishes: The foundations of welfare, community, and spiritual belonging in England.

She has produced a succinct and well-researched overview of the crisis facing Church of England parishes not just in rural areas but in our towns and cities too.

The discussion following had strong contributions from Danny Kruger MP, Imogen Sinclair, the Rev’d Marcus Walker of Great St Bart’s, Rebecca Chapman who sits on the Anglican Church’s General Synod, Eddie Tulasiewicz of the National Churches Trust, Bijan Omrani, and more.

As a devotee of England’s cult of the saints, what interested me particularly was the contribution from Rupert Sheldrake of the Choral Evensong Trust.

He explained that the CET was doing its bit for parish churches by creating a Patronal Festival Grants scheme to encourage more churches to celebrate the feast of their patron saint or dedication.

He explained that the CET was doing its bit for parish churches by creating a Patronal Festival Grants scheme to encourage more churches to celebrate the feast of their patron saint or dedication.

Grants of up to £500 are available to provide for choral evensong sung by a visiting choir and – deeply important – a party afterwards at which food and drink are free to those gathering.

“For example,” the Trust informs us, “at St Michael and All Angels in Dinder, near Wells, over ninety people attended a choral evensong on Michaelmas, sung by the Wells Cathedral Chamber Choir. The church was filled to capacity, with many attendees participating in church activities for the first time.”

This is a genius scheme for encouraging greater devotion to the saints as well as more frequent use of now sadly often shut C-of-E parish churches.

As it says in Deuteronomy, “thou shalt make merry in thy festival time, thou, thy son, and thy daughter, thy manservant, and thy maidservant, the Levite also and the stranger, and the fatherless and the widow that are within thy gates.”

More information on the CET’s 2025 Patronal Festival Grants can be found here and the deadline for next year’s applications is Candlemas (2 February 2025).

That evening I was a guest at high table in an Oxford college which is exhibiting signs of health and societal repair.

A few years ago, the head of house disregarded the strident protests of the students and banished the college grace as well as all dress codes for dining. (To the gratitude of many, she did not last long.)

After this unwelcome interruption, the college grace before meals has now been restored (in Latin), in addition to the return of formal meals with gowns (and, on Sundays, black tie).

In some place, where you let it and protect it, nature is healing.

Meanwhile, below, some beautiful music for Advent from my own parish church, St George’s Cathedral in Southwark.

This beautiful performance of Veni, Veni, Emmanuel by Malakai from St George’s Cathedral Choirs, performed at St George's Cathedral is a reminder that Jesus is God with us who witnessed to the love of the Father by dwelling among us.@StGeorgesCath @StGeorgesChoirs pic.twitter.com/L8VY31FmNA

— Archdiocese of Southwark (@RC_Southwark) December 5, 2024

Israel’s Hebrew-speaking Catholics

In Jerusalem I had the privilege of interviewing Fr Piotr Zelazko, the Polish priest who heads the Saint James Vicariate for Hebrew-Speaking Catholics.

The  community he looks after is a fascinating one and adds even more complexity to the rich tapestry of Christianity in the Holy Land.

community he looks after is a fascinating one and adds even more complexity to the rich tapestry of Christianity in the Holy Land.

The article is now up in its full form at the Catholic Herald online — including comments from Cardinal Pizzaballa, the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem — and a slightly shorter version appears in July’s summer issue of the magazine.

(My contribution to their summer books list is also in the July issue.)

Music, the Hospitallers, and the Tudors

This will take place in the Chapter Room of the Grand Priory of England at 7.00 pm on Thursday 18 July 2024.

All are welcome, and a voluntary contribution of £10 will be collected.

‘Knights of Massawa?’ Lecture

This will take place in the Chapter Room of the Grand Priory of England at 7.00 pm on Tuesday 19 March 2024.

All are welcome, and a voluntary contribution of £10 will be collected.

St Mary Overie in Lent

Here in Southwark I nipped in to Evensong in the late twilight of a winter’s day. They do it very beautifully with a full choir at the Protestant cathedral — old Southwark Priory or St Mary Overie to us Catholics, St Saviour’s to our separated brethren.

As it is the penitential season, the Lenten Array is up at Southwark Cathedral, theirs apparently designed by Sir Ninian Comper.

What is a Lenten Array? Sed Angli writes on the Lenten Array in general while Dr Allan Barton has written on Southwark Cathedral’s Lenten Array specifically.

And of course our friend the Rev Fr John Osman has one of the most beautiful Lenten Arrays at his extraordinary Catholic parish of St Birinus — a stunning church previously mentioned.

(The photograph of our local array is from Fr Lawrence Lew O.P.)

Die kleine dorpie Betlehem

JA JA JA, ons onthou: die Amerikaanse Episcopaalse biskop Phillips Brooks was nie ’n bolwerk van ortodoksie nie. Hy het die ryk van gevoel bo die waarheid verhef, maar nie noodwendig teen die waarheid nie — hulle het in die negentiende eeu nog ’n bietjie politesse gehad.

Soos R.R. Reno geskryf het: Brooks “het geen moeilike teologiese kwessies gedink of enige nuwe intellektuele grond gebreek nie.” In Nieu-Engeland was hy “heeltemal afgeleide en uiters invloedryk”.

Reg genoeg… en vandag leef ons in Brooks se nawêreld. Maar hy het ’n klein geskenk aan die wêreld gegee, en sy klein geskenkie was ’n lofsang — ’n Kersfees liedtjie.

Die wysie wat in Amerika gebruik word, is sakkarien. Maar die Britse een — “Forest Green” — is melodieus en goed. (’n Video hieronder, en Engels, gesing deur die koor van St George’s in Windsor-kasteel.)

lê rustig daardie nag,

terwyl dié wonderwerk gebeur

waarvoor die wêreld wag.

verskyn ’n nuwe dag

vir almal wat in nood verkeer

en op sy redding wag.

Toe God se Seun gebore is,

was daar geen plek vir Hom;

so word ’n donker dierestal

’n helder heiligdom.

verskyn ’n Koningster,

wat ewig lig en vrede straal

na mense wyd en ver.

O Koningskind daar in die krip,

U kom hier by ons woon.

Net U versoen ons sondeskuld

en maak ons lewe skoon.

want U kom ons herstel.

O Vredekoning, God met ons,

U is Immanuel.

Articles of Note: 6 January 2024

■ I had the great privilege of studying French Algeria under the knowledgeable and congenial Dr Stephen Tyre of St Andrews University and the country continues to exude an interest. The Algerian detective novelist Yasmina Khadra — nom de plume of the army officer Mohammed Moulessehoul — has attracted notice in Angledom since being translated from the Gallic into our vulgar tongue.

Recently the columnist Matthew Parris visited Algeria for leisurely purposes and reports on the experience.

■ While you’re at the Spectator, of course by now you should have already studied my lament for the excessive strength of widely available beers — provoked by the news that Sam Smith’s Brewery have increased the alcohol level of their trusty and reliable Alpine Lager.

■ This week Elijah Granet of the Legal Style Blog shared this numismatic gem. It makes one realise quite how dull our coin designs are these days. I don’t see why we shouldn’t have an updated version of this for our currently reigning Charles.

■ Meanwhile Chris Akers of Investors Chronicle and the Financial Times has gone on retreat to Scotland’s ancient abbey of Pluscarden and written up the experience for the FT. As he settled into the monastic rhythm, Chris found he was unwinding more than he ever has on any tropical beach.

Pluscarden is Britain’s only monastic community now in its original abbey, the building having been preserved — albeit greatly damaged until it was restarted in 1948. The older Buckfast is also on its original site but was entirely razed by 1800 or so and rebuilt from the 1900s onwards. (Pluscarden also has an excellent monastic shop.)

■ An entirely different and more disappointing form of retreat in Scottish religion is the (Presbyterian) state kirk’s decision to withdraw from tons of their smaller churches. St Monans is one of the mediæval gems of Fife, overlooking the harbour of the eponymous saint’s village since the fourteenth century, and built on the site of an earlier place of worship.

Cllr Sean Dillon pointed out the East Neuk is to lose six churches — some of which have been in the Kirk’s hands since they were confiscated at the Reformation, including St Monans.

John Lloyd, also of the FT, reported on this last summer and spoke to my old church history tutor, the Rev Dr Ian C. Bradley. More on the closures in the Courier and Fife Today.

What a dream it would be for a charitable trust to buy St Monans and to restore it to its appearance circa 1500 or so, available as a place of worship and as a living demonstration of Scotland’s rich and polychromatic culture that was so tragically destroyed in the sixteenth century. You could open with a Carver Mass conducted by Sir James MacMillan.

■ And finally, on the last day of MMXXIII, the architect Conor Lynch reports in from Connemara with this scene of idyllic bliss:

Regnum, Ecclesia, Studium

The threefold division of the world

As such he might be expected to have ideas about the idea of a university, and he wrote about them in The Spectator in August 1983.

Mister Grimond (as he still was then, only just), suggested those interested in the subject “might turn to a lecture by Ronald Cant, sometime Reader in Scottish History in the University of St Andrews”:

[…]

A vital aspect of this tripartite organisation, as Cant says, was that each should serve and support the other. But the studium, while interacting with the regnum and ecclesia, must maintain its independence.

It was certainly the business of the studium to advance knowledge, but that was not to be the end of the matter. Knowledge was linked to public service. The learned man had a duty to the community as well as a right to pursue his intellectual quarry. In fact he pursued the quarry on behalf of the community.

The tripartite division of the world, although old-fashioned, seems to me a useful concept, emphasising that government, morality, and higher education are separate but intertwined.

It seems to me that if we expel the regnum and the ecclesia utterly from the world of the university we shall end up paradoxically with universities totally dependent upon the state… but as subservient as those in Rome.

The liberal spirit gave birth and sustenance to universities; if its progeny does not foster it in the regnum they may indeed end up as purely vocational colleges.

Crisis Averted at Chartres

The rather garish and invasive plans to renovate the parvis of Chartres cathedral, turn it upside down, and install a museum underneath — previously reported on here in 2019 — have been radically revised in an infinitely less offensive direction.

The City of Chartres has released the final approved designs which show the esplanade of the cathedral renovated but left largely in place.

Instead of the original plan up reversing the grade of the parvis upwards away from the cathedral, the entire museum will be kept underground and out of sight. (more…)

The Ukrainians’ Secret Weapon

For those looking for an explanation as to the notable success of the Ukrainians on the battlefield in the current unpleasantness taking place in their country, look no further.

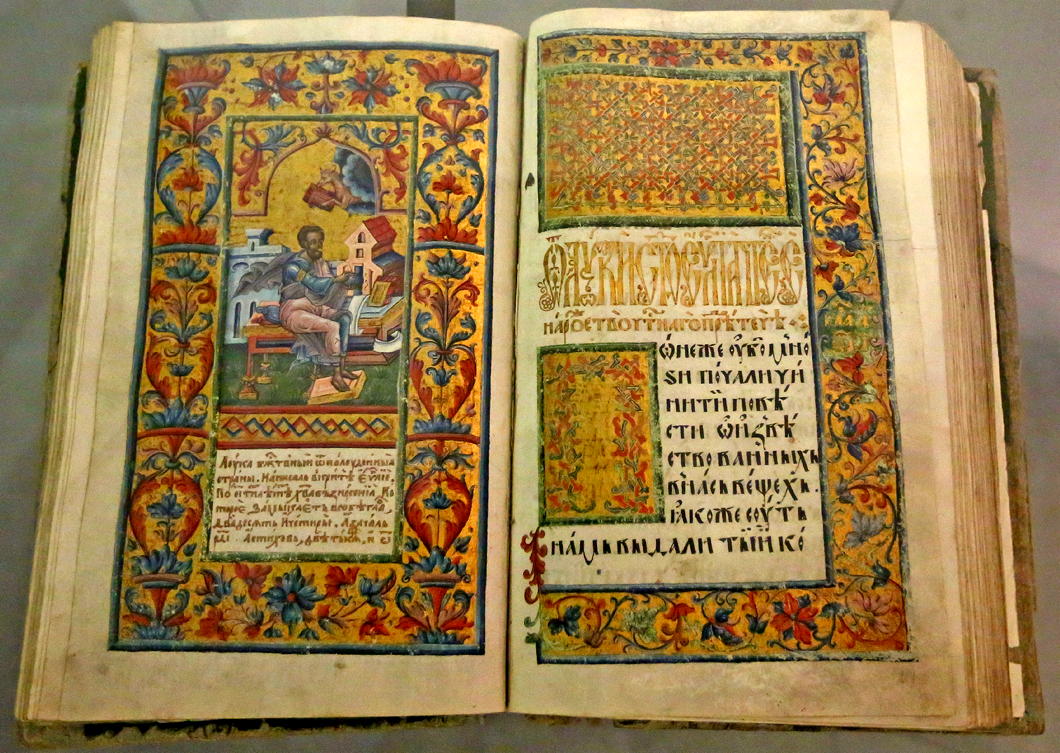

In a thread of tweets, the biblophile Incunabula reveals the Ukraine’s secret weapon: the Peresopnytsia Gospels (Пересопницьке Євангеліє).

“All six Ukrainian Presidents since 1991,” Incunabula writes, “including Volodymyr Zelensky, have taken the oath of office on this book: the sixteenth-century Peresopnytsia Gospels, one of the most remarkably illuminated of all surviving East Slavic manuscripts.”

“The Peresopnytsia Gospels were written between 15 August 1556 and 29 August 1561, at the Monastery of the Holy Trinity in Iziaslav, and the Monastery of the Mother of God in Peresopnytsia, Volyn.”

“This manuscript is the earliest complete surviving example of a vernacular Old Ukrainian translation of the Gospels. Its richly ornamented miniatures belong to the very highest achievements of the artistic tradition of the Ukrainian and Eastern Slavonic icon school.”

“The Peresopnytsya Gospels were commissioned in 1556 by Princess Nastacia Yuriyivna Zheslavska-Holshanska of Volyn, and her daughter and her son-in-law, Yevdokiya and Ivan Fedorovych Czartoryski. After its completion the book was kept in the Peresopnytsya Monastery.” (more…)

Special Mission to Rome

RELATIONS BETWEEN THE Court of St James’s and the Holy See have evolved in the many centuries since the Henrician usurpation. At times, such as during the Napoleonic unpleasantness, the interests of London and the Vatican were very closely aligned — despite the lack of full formal diplomatic relations. Later in the nineteenth century Lord Odo Russell was assigned to the British legation in Florence but resided at Rome as an unofficial envoy to the Pope.

It wasn’t until 1914 that the United Kingdom sent a formal mission to the Vatican, but this was a unique and un-reciprocated diplomatic endeavour — a full exchange of ambassadors would have to wait until 1982. (Until then, the Pope was represented in London only by an apostolic delegate to the country’s Catholic hierarchy rather than any representative to the Crown and its Government.)

Within a year of the Special Mission to Rome being established, John Duncan Gregory (later appointed CB and CMG) was assigned to it. A diplomat since 1902 who had previously worked in Vienna and Bucharest, he was one of the central figures in the curious ‘Francs Affair’ of 1928, when two British diplomats were believed to have unduly abused their positions to speculate in currency. Despite being cleared of illegality, J.D. Gregory was dismissed from his diplomatic posting — though he was later rehabilitated.

Within a year of the Special Mission to Rome being established, John Duncan Gregory (later appointed CB and CMG) was assigned to it. A diplomat since 1902 who had previously worked in Vienna and Bucharest, he was one of the central figures in the curious ‘Francs Affair’ of 1928, when two British diplomats were believed to have unduly abused their positions to speculate in currency. Despite being cleared of illegality, J.D. Gregory was dismissed from his diplomatic posting — though he was later rehabilitated.

If there are any enthusiasts of the curious subcategory of accoutrement known as the despatch box, J.D. Gregory’s one dating from his time in Rome is currently up for sale from the antiques dealer Gerald Mathias.

It was manufactured by John Peck & Son of Nelson Square, Blackfriars, Southwark — not very far at all from me as it happens. (more…)

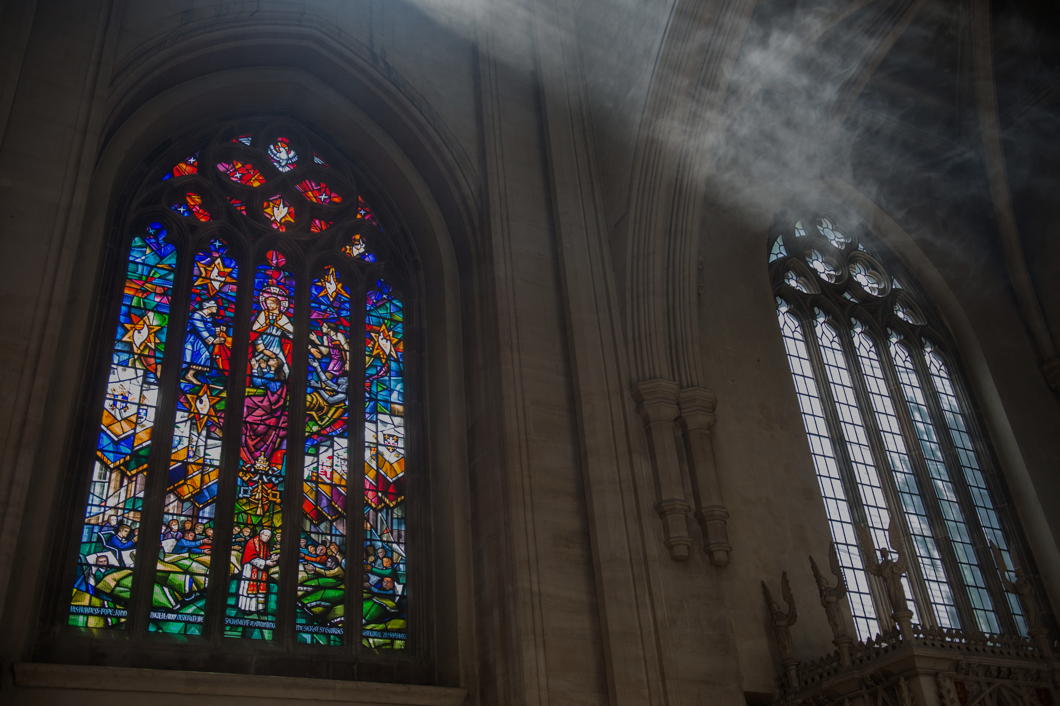

175 Years of St George’s Cathedral

ONE HUNDRED AND SEVENTY-FIVE years ago, at a time of great uncertainty in Europe, St George’s in Southwark was opened solemnly by Bishop Wiseman — writes the Cathedral Archivist Melanie Bunch. The ceremony was attended by thirteen other bishops in all their finery, of whom four were foreign. Hundreds of clergy of all ranks were in the procession and many of the Catholic aristocracy of England were present. The music was magnificent, the choir including professional singers.

Pugin’s neo-Gothic church was impressive but not finished, and it was not to be a cathedral for another four years. Dr Wiseman, who was both the chief celebrant and the preacher, was bishop of a titular see, as the Catholic dioceses of England and Wales did not yet exist. Nonetheless the opening marked a significant stage in the revival of the Catholic Church in this region. The spur had been the spiritual needs of the poor Irish who had long formed settled communities in parts of London and other cities. The plans for the church had been drawn up in 1839 – before the severity of the famine in Ireland, which began in 1845, could have been foreseen. Some had considered the size of the new church unnecessary, but it turned out to be providential, as immigration from Ireland to this locality and elsewhere was reaching a peak at this time.

The extraordinary turmoil in Europe that had started early in the year in Sicily could not be ignored. In February Louis-Philippe was dethroned in France. There was anxiety that revolution might cross the Channel. Pugin decided that he should obtain muskets to defend his church of St Augustine under construction in Ramsgate. Revolution spread to German and Italian states and countries under Austrian rule. For four days in late June, there was a brief and bloody civil uprising in Paris.

While Europe was ablaze, London was calm, and the opening went ahead. In his homily, Wiseman praised God for all his mercies to this country. From our perspective, we might have expected that he would have spoken about the dark days of persecution, or at least the struggles of the recent past to get such a large church built, constantly hampered by lack of funds. Rev. Dr Thomas Doyle, whom we honour as the founder of the Cathedral, was present and assisting at the Mass, but his courage, faith, and dogged persistence over many years were not acknowledged on this occasion.

We might remember that a Catholic event like this had not been witnessed in England since the Reformation, seemingly prompting Wiseman to take the opportunity to explain to the non-Catholics present that the ceremony and display of the Catholic Church came from a desire to show greater respect for God. To the foreign bishops he said that their presence proved the unity and diversity of the Church. At the end of his homily, Wiseman caused a sensation by reading out a letter from the Archbishop of Paris, Mgr Affre, regretting that he could not attend the opening. By then it was known that he had already died from wounds received on the barricades while he was trying to mediate with the rebels. Wiseman called him a martyr.

Among others who never saw the opening are some who served St George’s mission with Thomas Doyle at the earlier chapel in London Road. Three of them had died before their time, only a few years before, from diseases endemic among their flock. We remember them and all who have served the Cathedral with gratitude. At the time of the opening, St George’s was the largest Catholic church in London, and for the next fifty years was to be the centre of Catholic life in the metropolis. Much has changed since, including the rebuilding of the Cathedral, but we give thanks to Almighty God who continues to sustain it. (more…)

A Night Litany for London

Wanderers in central London who find themselves in the whereabouts of Piccadilly Circus or Soho of a Tuesday evening can avail themselves of the devotions offered by the Guild of Our Lady of Warwick Street.

Every week, the Rosary is said along with other prayers at this statue in Warwick Street Church. They conclude with the rather beautiful and moving ‘Night Litany for London’ imploring God’s mercy upon the many inhabitants of our capital city.

Its original form is believed to have been composed by the Rev’d H.A. Wilson, vicar of the Protestant parish of St Augustine in Haggerston. Msgr Graham Leonard — in the days when he was Anglican Bishop of London — also published a version through the Church Literature Association (a High Church body) with an introduction he wrote himself.

The version used at Warwick Street is included here:

OUR LADY of Warwick Street,

we plead before Thee

to present our prayers before the Throne of Grace

for all in this great city of London

who tonight need Thy merciful love and protection.

ON ALL who work tonight —— Lord, have mercy.

On the police, fire, and ambulance services —— Lord, have mercy.

On hospitals, doctors, and nurses —— Lord, have mercy.

On clergy and chaplains called out tonight —— Lord, have mercy.

On the homeless and destitute —— Lord, have mercy.

On all lost and vulnerable people —— Lord, have mercy.

On the lonely —— Lord, have mercy.

On the elderly —— Lord, have mercy.

On abused children —— Lord, have mercy.

On loveless marriages and broken homes —— Lord, have mercy.

On those who self-harm —— Lord, have mercy.

On the sick and suffering —— Lord, have mercy.

On the mentally ill —— Lord, have mercy.

On those undergoing operations —— Lord, have mercy.

On those who cannot sleep tonight —— Lord, have mercy.

On those who are depressed —— Lord, have mercy.

On those who misuse the internet —— Lord, have mercy.

On all prisoners and prison staff —— Lord, have mercy.

On all prostitutes and their clients —— Lord, have mercy.

On those addicted to alcohol and drugs —— Lord, have mercy.

On all immigrants feeling lonely and insecure tonight —— Lord, have mercy.

On all who live in fear —— Lord, have mercy.

On all victims of crime —— Lord, have mercy.

On those planning to commit a crime tonight —— Lord, have mercy.

On those who are driving tonight —— Lord, have mercy.

On all involved in accidents —— Lord, have mercy.

On those who are bereaved tonight —— Lord, have mercy.

On those for whom tonight will be their last on earth —— Lord, have mercy.

On those dying without the knowledge of Thy Love for them —— Lord, have mercy.

On those who are afraid to die —— Lord, have mercy.

On those tempted to suicide —— Lord, have mercy.

On the terminally ill —— Lord, have mercy.

On ourselves at our last hour —— Lord, have mercy.

ON BEHALF of all Londoners who today have said no prayers, let us say together:

Our Father …

Hail Mary …

℣. Most Sacred Heart of Jesus: ℟. Have mercy upon us. (thrice)

Celebrating Saint Nicholas in New York

As any fool knows, the great city of New York has as its patron and protector a great and holy saint, the wonderworker Nicholas of Myra (AD 270-343).

A great city and a great saint merit a great feast, and since 1835 the Society of Saint Nicholas in the City of New York has risen to the task of commemorating the holy bishop as well as rendering honour to our Dutch forefathers of old who founded New Amsterdam in the colony of New Netherland where the waters of the Hudson meet the Atlantic Ocean.

Blustering through the archives, it is rewarding to read of how this feast has been kept over the years.

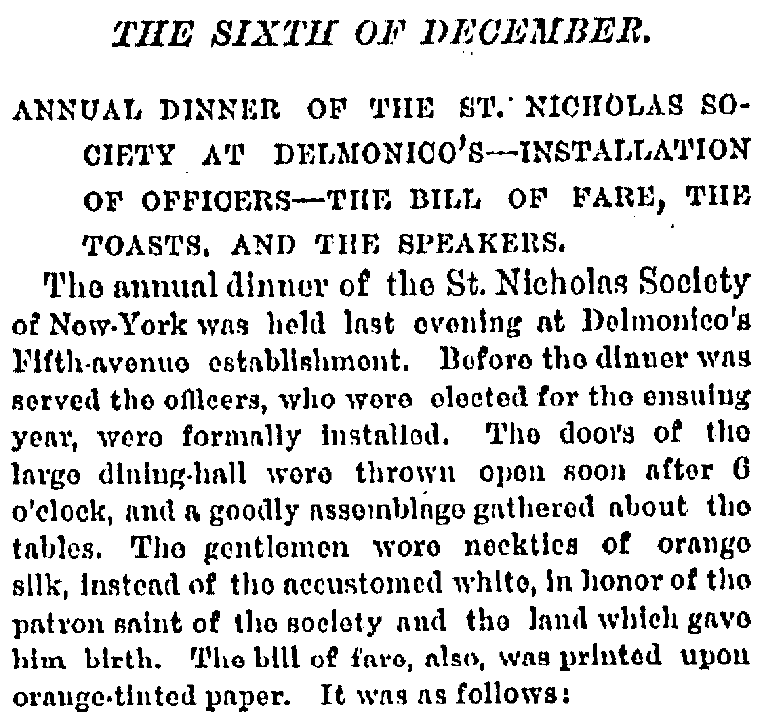

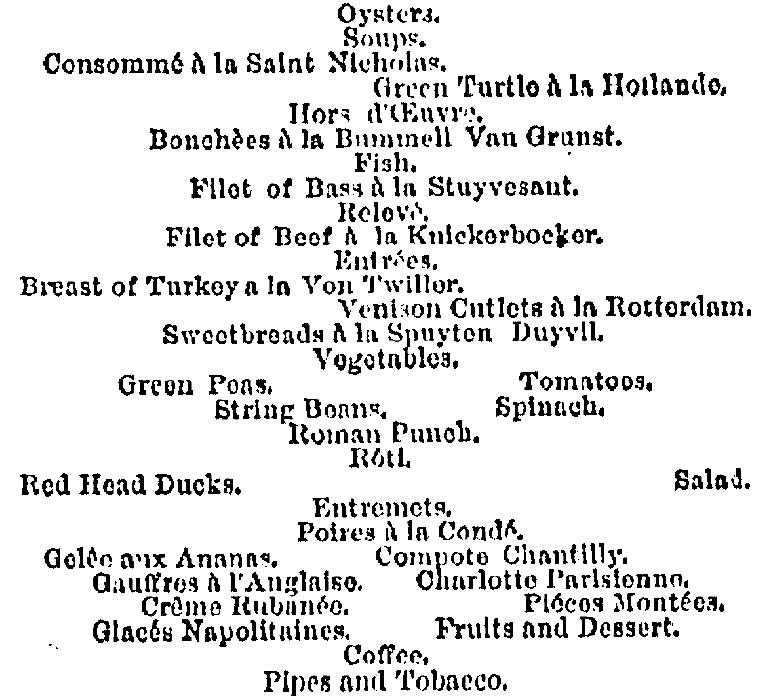

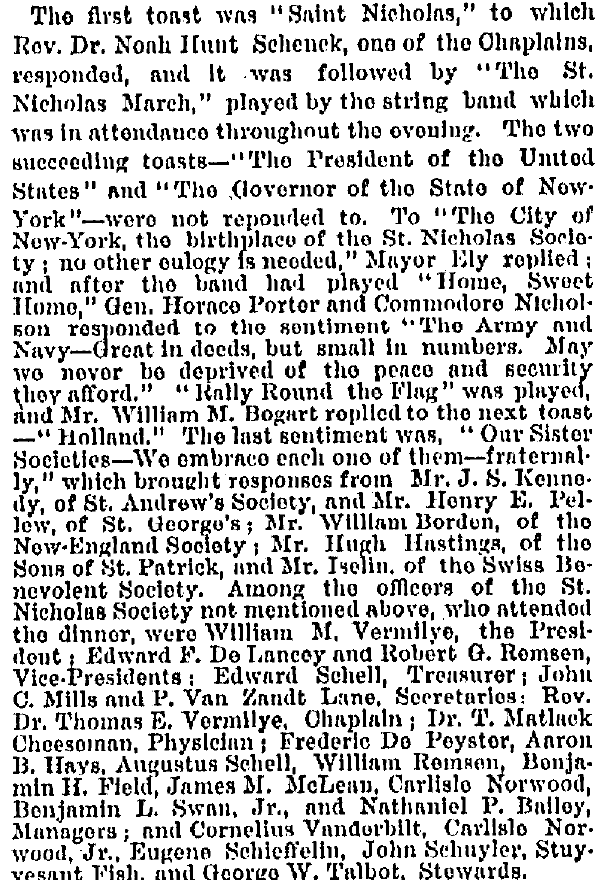

This little snippet from The New York Times relays the St Nicholas Society’s feasting in 1877:

Sounds like quite a meal, but it was followed by toasts and responses appropriate to St Nicholas Day and to the city:

Just over a decade later in 1888, the Times again gives its report on what sounds like an amusing evening:

After an elaborate dinner had been discussed and as the coffee and long clay pipes were handed around, the old weathercock that Washington Irving gave the society was brought in and placed at its post of honor before the President, and the toast-making was begun. Austin G. Fox replied to the toast “Saint Nicholas,” and paid an eloquent tribute to the memory of W. H. Bogart of Aurora, N.Y., who had answered that sentiment at nearly every previous dinner.

The toast “The President of the United States” was drank standing and was lustily cheered. Ex-Judge Henry E. Howland made a witty response to “The Governor of the State of New-York,” touching upon every other imaginable subject but the one to which he was to respond, and James C. Carter responded to “Our City.” The Rev. Dr. J.T. Duryea spoke to “Holland,” and Warner Miller, in the absence of Gen. Sherman, replied to “The Army and Navy.” Joseph H. Choate made a characteristic reply to “The Founders of New-Amsterdam.”

The newspaper further relates that: “At the request of the St. Nicholas Society, Mayor Hewitt had flags displayed on the City Hall yesterday in honor of the festival of St. Nicholas, the patron of this city.”

In 1907, the Society’s members and guests marched into dinner at Delmonico’s two-by-two, preceded by a trumpeter and twelve servants “clad in the black and orange liveries of early Holland” escorting the newly elected president, Col. William Jay.

Another tradition of the evening kept each year was “the carrying round the great room of the bronze rooster that at one time surmounted the first City Hall built in New York by the Dutch in the seventeenth century”. The weathervane was presented to the Society by Washington Irving, its first Secretary, back in 1835. Some years the weathervane was oriented in turn to each speaker giving the response to the toasts accordingly.

Again, in 1907, one Dr Vandyke toasted the health of St Nicholas who “gladdens youth and makes the old seem young”. The Times relates:

“He explained that the long clay pipes which had been handed round to each guest was an old Dutch custom on St. Nicholas night. If a man got home with the pipe intact he was considered sober. Sad to relate, he said, it was the habit of those persons who had broken their own pipes to stand outside the tavern doors and break those of their more sober-minded brethren.”

While the St Nicholas Society has ancestral requirements for its membership, there are no such restrictions for the hospitable group’s guests. By the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Society in 1910, even we Irish we invited:

“William D. Murphy, who was called upon to give the toast of “Our City” said that he, an Irishman, was there at the feast for three reasons — first, because the Dutch founded the city; second, that the English took it away from them, and lastly, the Irish had it now.”

By 1919, New Yorkers were living in a changed world, with the war only just passed, and the dreaded Prohibition ever present. In that year, the Times reports that the speakers “expressed their opinions of Bolshevism, communism, and prohibition at their eighty-fourth annual dinner at Delmonico’s last night.”

Happily, these sons of Holland and devotees of Saint Nicholas kept his holy day festive despite the restrictions in place:

“Supreme Court Justice Victor J. Dowling, who was one of the speakers, expressed his thanks to the society for the Constitutional violations that had been provided for him.”

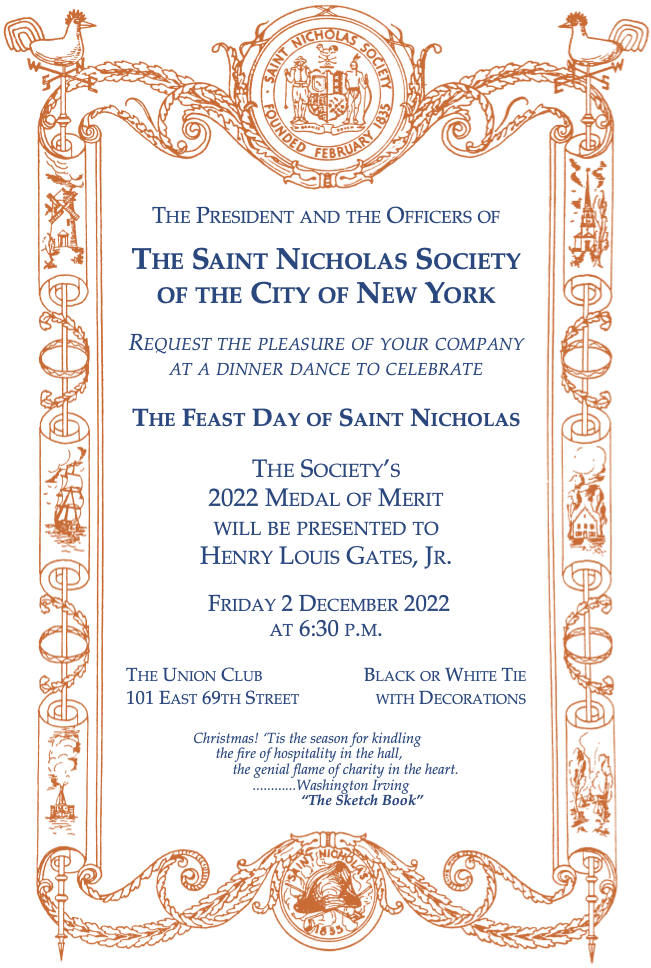

Lest you fear that the days (or nights) of celebrating this holy saint have faded into the folds of yesteryear, the Saint Nicholas Society of the City of New York is still in excellent health, and does not fail to keep the feast in accordance with the ways of its forefathers.

Indeed, the Society’s newsletter reported in 2018 that,

“Chief Steward Maximilian G. M. deCuyper Cadmus led the traditional procession of the Weathercock, which was raised high all around the room as members and guests energetically waved their napkins to generate a breeze that would waft him onto his perch near the lectern, facing east so as to crow out a warning in case of the approach of invaders from New England.”

This year the Society celebrated at the Union Club, and presented its Medal of Merit to the Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, Jnr.

Advent Missa Cantata at St George’s

St George’s Cathedral

Lambeth Road, Southwark, London SE1 6HR

LAMBETH NORTH (Bakerloo)

ELEPHANT & CASTLE (Northern, Bakerloo)

Buses: C10, 360, 12, 453, 138, 53

A collection will be taken to defray the costs.

The Lady Chapel is to the right at the end of the north aisle of the Cathedral (on your right as you enter).

Earlier in the morning, as every Saturday at St George’s Cathedral, there will be Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament from 10:00 to 11:00 am, during which time Confessions will be heard.

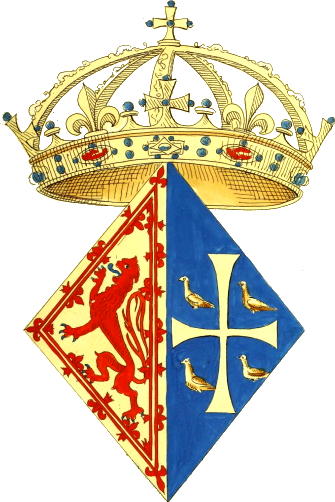

St Margaret Relic Heads to St Andrews

Students from St Andrews University have accompanied their Catholic chaplain to receive a relic of St Margaret of Scotland from the Archbishop of St Andrews & Edinburgh, Dr Leo Cushley.

The relic was put in the care of Canmore, the Catholic chaplaincy at St Andrews, whose chapel is dedicated to the Hungary-born English princess who became Scotland’s saintly queen.

When the relic in St Margaret’s Church in Dunfermline — the country’s royal centre in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries — were being removed from their reliquary the piece of bone fragmented.

The Archdiocese decided to make this an opportunity for the relics of the royal saint to be distributed further.

This relic of St Margaret will remain in Canmore where it will be available for veneration by students and other visitors.

SAINT MARGARET

QUEEN OF SCOTLAND

pray for us

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- How to Make a Pope April 24, 2025

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories