Arts & Culture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Manor House

For devoted fanatics of Netherlandic architecture — I’m sure you’d count yourself as one as much as I do — a curious example of Dutch revival architecture can be found at No. 316 Green Lanes in the Borough of Hackney. Alighting from Manor House tube station the other day I was surprised to find myself confronted by a fine building which, it turns out, used to be the pub that gave its name to the Underground station.

The first ‘public house and tea-gardens’ of that name was built in the 1830s, and in 1843 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert stopped there for a change of horses. This tavern soldiered on until the arrival of the Piccadilly line which necessitated street widening and the demolition of the pub in 1930.

It was rebuilt in a very handsome brick Netherlandic revival in 1931 and continued on as a pub supplied by the London brewers Watneys.

A purist would object that the style of windows on the gables suggests a vulgar pakhuis (warehouse) on the Amstel while the stepped gable itself is more informed by domestic architecture. But is the privilege of architectural revivals to mix and match, so I don’t think we should complain.

Evidence suggests the pub shut in 2004 and the building was converted to its current retail use.

Alas, I can find no record of the architect, and the building remains un-listed, but I’m glad Hackney is home to this happy Hollandic interloper.

British Columbia in London

Colonial Agents & Provincial Agents-General in the Imperial Capital

JUST WHERE THE elegant Edwardian urbanity of Waterloo Place turns into Regent Street there is an edifice that announces itself as home to the “Agent General for British Columbia”. Built in 1914-1915, it was designed by a not particularly prominent architect named Alfred Burr who did a lot of work for the Metropolitan Police and is also responsible for designing the charming little curator’s lodgings next to Dr Johnson’s House (which he restored 1911-1912).

The listing that protects British Columbia House, at 1-3 Regent Street, describes its style as “rich Baroque with both Roman and Genoese palazzo features composed on a large scale”.

The main entrance is on Regent Street with the province’s delightfully sunny coat of arms carved above the portal, guarded by allegorical figures of Justice and the like above. On the corner with Charles II Street, the inscription on the foundation stone proclaims its laying at the hands of Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught on the sixteenth day of July in 1914.

But who or what on earth was the Agent General for British Columbia? (more…)

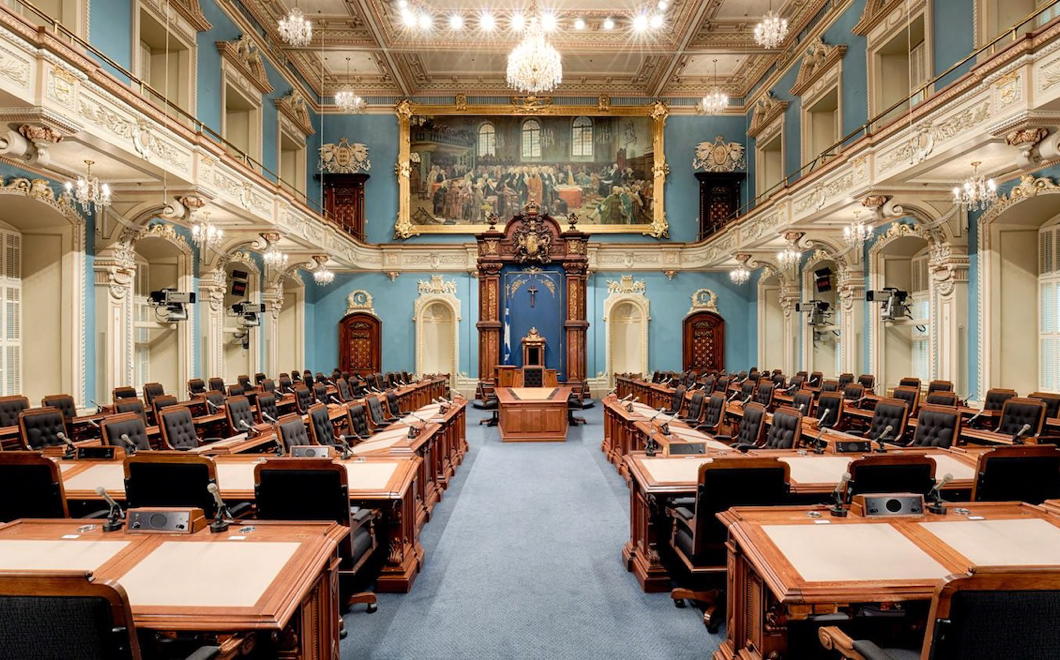

The politics of parliamentary colour

When Quebec’s « Salon bleu » was the « Salon vert »

One Westminster tradition replicated in many times and places across the Commonwealth is a convention of colour: the lower house of a parliament is decorated in green, while the upper chamber is decorated in red. This reflects the green benches of the House of Commons and the red ones of the House of Lords.

Officially the plenary chamber of Quebec’s unicameral parliament is boringly the salle de l’Assemblée nationale but because of the colour of its walls it is more often known as the Salon bleu. One’s never surprised when Quebec bucks a trend or (more specifically) rejects an Anglo convention but it turns out the province’s plenary chamber did in fact used to be green until relatively recently.

When the members of the Legislative Assembly (as it then was) first convened in the Hôtel du Parlement in 1886 the walls were actually white. By the opening of the 1895 session the desks had been reappointed in green, but Le Soleil still made reference to the room as the “chambre blanche”. It was only in 1901 that the room was painted a “soft green” and the carpets and other furnishings changed accordingly. It even made an appearance in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1953 film “I Confess”.

From then the chamber was a Salon vert until 1978, when the decision was taken to begin broadcasting the proceedings of the Assemblée nationale.

The television specialists complained that the dark green of the chamber was not visually conducive to the TV cameras available at the time and, looking at the evidence from the 1977 test session (above), one can see their point. Walls of either beige or blue were the options recommended in an official report, and unsurprisingly the national colour was chosen.

The historian Gaston Deschênes has mentioned the technical requirements of broadcasting also coincided with a desire to break with a “British” tradition. Certainly the government of the day, René Lévesque’s Parti Québécois, didn’t mind the change, while Maurice Bellemare — “the old lion of Quebec politics” and sometime leader of the old Union nationale — was deeply pleased that the chamber adopted the colour of Quebec’s flag.

So the walls were repainted sky blue and the furnishings changed accordingly, resulting in the Salon bleu we know today (below).

A tweet from the Assemblée’s official account shows two photos looking towards the chamber’s entrance from before (above) and after (below) it was made ready for television.

All the same, green is not universal amongst Commonwealth lower (or only) chambers. It’s not even universal in Canada: Manitoba joins Quebec in its azure tones while British Columbia’s is red-dominated.

Quebec was the last of Canada’s provinces to abolish its upper house, the Legislative Council, in 1968 (at the same time the lower house was renamed the National Assembly). The Legislative Council’s former meeting place is, of course, red, and the Salon rouge is used for important occasions like inductions into the Ordre national du Québec or the lying-in-state of the late Jacques Parizeau.

The Palais de Tokyo

In the early 1930s the City of Paris decided the Musée de Luxembourg had become too small to continue as the city’s gallery of contemporary art. At the same time, the French Republic was beginning to think it needed a proper museum of modern art to display its own collections as well. The City and the Republic joined forces to build a new palace of art in time for the 1937 International Exposition.

While the City and the Republic would house their collections at a single site the museums were to remain separate, so in May 1937 the Palace of the Museums (plural) of Modern Art was inaugurated by President Lebrun.

Because of its riparian location on the Avenue de Tokio (renamed to Avenue de New-York in 1945) the building quickly became known as the Palais de Tokyo. (more…)

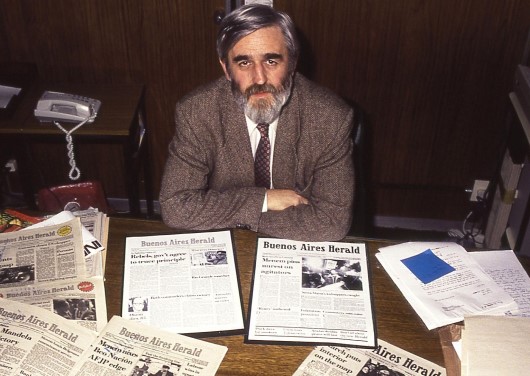

Andrew Graham-Yooll

A giant of Argentine journalism died this summer: Andrew Graham-Yooll.

Born in Buenos Aires early in 1944 to a Scottish father and an English mother, Graham-Yooll made his name at the premier institution of Anglo-Argentina, the now-defunct daily Buenos Aires Herald which he joined aged 22 in 1966.

“The Herald newsdesk supped for Dutch courage a local brandy,” the Times notes, “supplemented with a pâté that Graham-Yooll made of goose livers lashed with gin. A chain-smoker, he would construct tiny houses from matchsticks.”

As the Herald’s news editor during Isabel Perón’s presidency he published the names of dissidents who had gone missing or “disappeared” and, more bravely, continued to do so after Señora Perón was succeeded by a military junta.

The new rulers, who Borges warmly welcomed as “gentlemen”, put Graham-Yooll on trial for publishing interviews with the guerrillas who were terrorising the country. He was acquitted, but accepted the gentle advice of the judge who suggested he might find existence more comfortable outside the borders of the Argentine Republic.

Graham-Yooll continued writing for the Daily Telegraph and Guardian in Great Britain but made a brief foray home in 1982 during the Falklands War before being permanently welcomed home by a democratic government in 1984. Ten years later he was appointed editor of the Herald.

“Things you think you can rely on and trust are just not there,” Graham-Yooll said in Edinburgh when picking up his OBE in 2002.

“You can’t trust the bank, you can’t trust the post office or the people who sell you a house. You can’t trust the politicians, obviously. It’s a friendly society but it lacks strict rules. It’s evil, but it is also attractive to live in a place where you don’t have to live by rules.”

“I don’t know where I could go now. It was always home, even in the worst days, and it still is.”

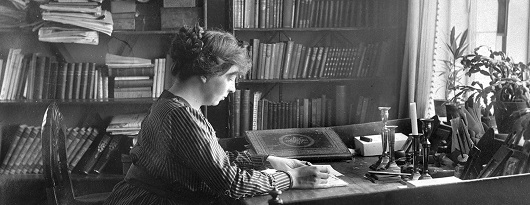

Understanding Undset

Sigrid Undset’s is doubtlessly among the twentieth century’s greatest writers, even though Kristin Lavransdatter, her main works of literature, is set in the fourteenth century. At the ceremony awarding Undset the 1928 Nobel Prize for Literature, Per Hallström described the writer’s narrative as “vigorous, sweeping, and at times heavy”:

It rolls on like a river, ceaselessly receiving new tributaries whose course the author also describes, at the risk of overtaxing the reader’s memory. […] And the vast river, whose course is difficult to embrace comprehensively, rolls its powerful waves which carry along the reader, plunged into a sort of torpor. But the roaring of its waters has the eternal freshness of nature. In the rapids and in the falls, the reader finds the enchantment which emanates from the power of the elements, as in the vast mirror of the lakes he notices a reflection of immensity, with the vision there of all possible greatness in human nature. Then, when the river reaches the sea, when Kristin Lavransdatter has fought to the end the battle of her life, no one complains of the length of the course which accumulated so overwhelming a depth and profundity in her destiny. In the poetry of all times, there are few scenes of comparable excellence.

Obviously Kristin Lavransdatter must be read for itself. I started reading it in the Stellenbosch University library a decade ago and was able to finish it thanks to being given a copy by a kindly Premonstratensian.

But the woman behind Kristin wrote more: her biographical essays and other works (like the one describing a visit to Glastonbury) are just as enjoyable and insightful.

At First Things, Elizabeth Scalia describes Undset’s lives of saints and holy men and women in Sigrid Undset’s Essays for Our Time.

Stephen Sparrow reveals much of Undset’s own biographical detail and how this influenced her writing in Sigrid Undset: Catholic Viking.

But the best essay I’ve read on Sigrid Undset so far is David Warren’s meditation on womanhood, motherhood, and Kristin Lavransdatter. I don’t agree with everything he says (I rather enjoyed the new translation but am thinking I might have to give the old one a go), but David gets Kristin the character, gets Kristin the novel, and gets the way that life is refracted through both.

Read David Warren, then read Sigrid Undset.

Lady Day

Today is Lady Day, the Feast of the Annunciation when the Archangel Gabriel appeared to the Blessed Virgin Mary and announced that she would conceive and bear the child Jesus.

The angelic salutation – “Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee… Blessed art thou amongst women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus” – forms the basis of the Ave Maria, one of the most widely uttered prayers in Christendom.

Traditionally this has been one of the greatest of devotions to the Virgin amongst the English, which is why there are so many pubs across England named ‘The Salutation’.

For centuries in England and Scotland (as well as elsewhere), Lady Day was the first day of the calendar year. Scotland moved this to 1 January in 1600 and England did likewise in 1750.

Nonetheless, the English tax year is still based on this date as it commences on 6 April, which is the Annunciation plus twelve days to mark the difference between the old Julian calendar and the modern Gregorian one.

In the realms of fiction, 25 March is the day Tolkien chose for when Frodo destroyed the Ring in Mount Doom, securing the fall of Sauron – with obvious parallels to Christ’s Incarnation securing the defeat of Satan.

This stained glass roundel above is not English, however, but from the Southern Netherlands around 1500-1510.

Elsewhere, A Clerk of Oxford has a good section on the Annunciation.

Haussmanhattan

Paris and New York are two cities radically different in design and character, but they are smashed together in this little project from architect Luis Fernandes.

‘Haussmanhattan’ is a portmanteau of Baron Haussmann, the Prefect of the Seine whose reconfiguration of the French capital made it the Paris we know today, and Manhattan, the most renowned of New York City’s five boroughs.

Haussmann’s plan of broad boulevards and radial avenues is a far cry from the artless Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 which created the unforgiving city blocks that colonised the entire island of Manhattan ad infinitum.

The contrast only makes the pick-and-mix Fernandes has confected all the more fun/ridiculous/interesting.

Sir John Soane

Sir John Soane still looms over the intervening centuries of architecture and design in Great Britain, but I’ve never actually known what he looked like. Apparently this is him, in an 1804 portrait by William Owen.

Everyone’s been to his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but Pitzhanger Manor, his place in the country (though Ealing hardly seems rural today) was recently reopened after serious conservation works ongoing since 2015.

Hope to pay it a visit soon.

The Rensselaer Window

The patroonship of Rensselaerswyck was erected in 1630 giving its patroon, Kiliaen van Rensselaer, feudal powers over a large parcel of land on the banks of the Hudson River. Despite exercising a strong influence on the growth and development of New Netherland and the Hudson Valley, Kiliaen never actually stepped foot in the new world but kept close control of his domain from across the ocean in Amsterdam.

Jan Baptist was Kiliaen’s second surviving son, and served as director at the ‘colony’ as it was often known from 1652 to 1658. He commissioned Evert Duyckinck to make this painted-glass window displaying his coat of arms in 1656 and gave it to the Dutch Reformed Church in Beverwyck (today’s Albany).

While the congregation still exists — and celebrated its 375th anniversary in 2017 — the original church was demolished in 1805 and the window moved to the Van Rensselaer Manor House which itself survived til 1890 before facing the wrecking ball. The window was preserved and was left to the Metropolitan Museum of Art through the 1951 bequest of Mrs J. Insley Blair and while well documented it does not appear to be on display at the moment.

The patroonship itself was converted into a manorial lordship by the English authorities after they took over and survived until it was broken up amongst relatives after the death of Stephen van Rensselaer III in 1839.

This last great patroon had proved an indulgent lord and the efforts of his inheritors to claim uncollected back rents led to the 1839-1845 “Helderberg War” or “Anti-Rent War” of tenants revolting against the system. The great landholders, seeing the end was nigh, were convinced to sell up and in 1846 the state of New York adopted a new constitution abolishing feudal tenure. The era of patroonships and manors in the Hudson Valley had come to an end.

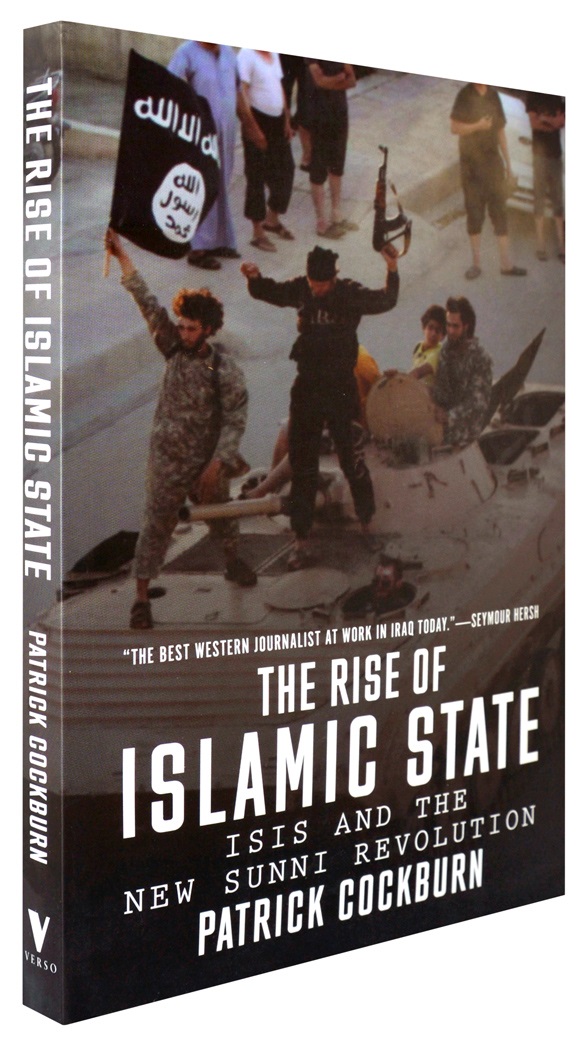

The Dawn of Da’esh

Patrick Cockburn, 192 pages, £9.99 (Verso Books, London)

words that flow confidently off the page and exude a sense of first-hand knowledge and on-the-ground insight, it’s easy to see how Patrick Cockburn has attained his reputation amongst those in the know as the foremost and most authoritative Western correspondent in the Middle East today. The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution (Verso Books, February 2015) attempts to sketch out the meteoric rise of the soi-disant caliphate’s black-clad gunmen and the factors which have facilitated it. This is no easy task, and while Cockburn does not quite achieve it, his effort is deeply informative—it is hard to imagine anyone could do better than he has in relaying the astounding complexity of the situation in Iraq and Syria today.

words that flow confidently off the page and exude a sense of first-hand knowledge and on-the-ground insight, it’s easy to see how Patrick Cockburn has attained his reputation amongst those in the know as the foremost and most authoritative Western correspondent in the Middle East today. The Rise of Islamic State: ISIS and the New Sunni Revolution (Verso Books, February 2015) attempts to sketch out the meteoric rise of the soi-disant caliphate’s black-clad gunmen and the factors which have facilitated it. This is no easy task, and while Cockburn does not quite achieve it, his effort is deeply informative—it is hard to imagine anyone could do better than he has in relaying the astounding complexity of the situation in Iraq and Syria today.

Much of the novelty of ISIS lies in the suddenness of their appearance and the continuous string of victories they have amassed. Cockburn is quick to point out that much of this is propaganda: ISIS has been a player in the region for years, but mostly as an authorised bin Laden franchise founded by the Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and under the name of Al-Qaeda in Iraq. Following al-Zarqawi’s death, the Sunni jihadist group transformed into the Islamic State in Iraq and proclaimed its new leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi the ‘emir’, expanding operations into Syria by 2013.

Despite numerous successful terrorist attacks and assassinations, it is the capture of Mosul in June 2014 which Cockburn singles out as the start of ISIS as the phenomenon we are experiencing today. This stellar rise has yet to prove fully meteoric in the sense that, while their onward march has ground to a halt at Kobane, ISIS has stubbornly refused to burn out and fade away. This has been contingent upon an alignment of factors which might be oversimplified into three: the endemic corruption of the Iraqi state, the astounding stupidity of Western powers, and the entrenched sectarianism of Iraqi society.

As one of the most central institutions of the state, the melting-away of the Iraqi Army’s resistance to ISIS has been crucial. It is difficult to overestimate the vast scale of corruption in the Army. Military units often include large numbers of troops that exist only on paper. Command of a division comes with a high pricetag. Having borrowed the money to pay for it, divisional commanders then require steady income streams to pay back the loan. Setting up roadblocks to extort money from travellers is an easy task for an armed force, but the possibilities are numerous.

A retired Iraqi general tells Cockburn the rot first set in when, in 2005, the Americans demanded the Iraqi Army outsource food and logistical supply:

“A battalion commander was paid for a unit of 600 soldiers, but had only 200 men under arms and pocketed the difference, which meant enormous profits.”

In Mosul, Cockburn points out, only one in three of the soldiers meant to be there were physically present, the rest having payed up to half their salaries to be on permanent leave.

Endemic corruption of this kind has been fostered by the complacency of the governing elite. A Turkish businessman was ruffled when a local ISIS leader demanded $500,000 per month in protection money. “I complained again and again to the government in Baghdad,” he relates to Cockburn, “but they would do nothing about it except to say that I should add the money I paid to al-Qaeda to the contract price.” Such an attitude hardly inspires confidence in the state.

As ISIS gained ground across Iraq, the Baghdad elite seemed only to increase its insularity, acting as if nothing was wrong. “When you speak to any political leader in Baghdad,” an ex-minister says, “they talk as if they had not just lost the country.”

“ISIS,” Cockburn points out, “are experts in fear.” YouTube has been deployed with a methodical exactness towards this end. The talking heads who’ve preached the gospel of new media as breaking down barriers and leading to an immanent global liberation have plainly failed to grasp that these new forms of communication can be expertly employed by forces intrinsically opposed to their vision of a liberal utopia.

While the Shi’ites have long been in the majority, the Sunnis were top-dog under Saddam, widely favoured and occupying places of power and authority. With Saddam toppled and democratic elections now forming the basis of the state’s legitimacy, the numerical strength of the Shia has handed the state to Shi’ite political forces fearful of a return to the old days. When Sunnis complain of violence, intimidation, and discrimination at the hands of the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad, Shi’ites don’t see the Sunnis as reacting to oppression but as plotting a return to their former dominance.

This de-legitimisation of the official state in the eyes of Sunni Iraqis has provided the space in which the zealous ISIS has come to the fore. Where ISIS rules it is widely unpopular – in a country of smokers, Cockburn notes, they have demanded bonfires of cigarettes in captured towns – but too many of ISIS’s enemies are opposed to all Sunnis, not just ISIS. This means Sunnis opposed to ISIS have no one to turn to for protection or support. All too many have calculated that enforced piety and oppression from ISIS are preferable to being murdered by Shia militiamen in police uniforms just for being Sunni.

But one of the most influential factors in the rise of the Islamic State in Iraq has been events in neighbouring Syria. Shifting his aim westwards, Cockburn provides analysis of events that is both illuminating and frustrating. The interference of external powers in Syria, whether Middle-Eastern or Western, has had catastrophic and usually counter-productive effect. In the midst of a supposed ‘global war’ on Islamic terror, the logic of toppling yet another bastion of Ba’athist-style dictatorial secularism in the region is murky. Encouraging a Sunni uprising in Syria without foreseeing a knock-on effect in neighbouring Iraq also strikes Cockburn as particularly naive.

The vitality of continued opposition to Assad by the US-led Western powers and by states in the region is astonishing – almost satanic. The United States happily allied itself with the most murderous force in the twentieth century – the USSR – in order to defeat the more pressing evil of Nazi Germany. And yet the exponentially milder Assad regime is somehow considered totally untouchable – or ‘haram’ as the locals of the region might say. It was only twenty-odd years ago Syrian troops were fighting as part of the US-led coalition in the First Gulf War. The transformation since then is inexplicable (and, with his hands already full, Cockburn does not attempt to offer any insight into this).

Despite the severity of the civil war being waged in Syria, the West has demonstrated openly and brazenly that it is more interested in eliminating Assad than ending the war. As Cockburn frequently points out, Assad has continuously been in control of all but two regional capitals in Syria, yet the United States says he can’t even have a place at the negotiating table unless he agrees to give up power. That’s not a pre-condition: it’s a repudiation. Failed politicians in this part of the world don’t retire to bank boards and book deals like in the West – more often their bloodied corpses are dragged from their palaces by a mob of well-orchestrated ferocity. (The victors’ justice of Saddam’s execution is a rare example that tests the rule.)

Laying the Assad-must-go precondition is a bold statement by Western powers that they grant zero priority to ending the war. Despite all their high-minded liberal humanitarian cover talk, it’s simply not on the agenda: Power is the only thing.

Despite the unsurprisingly depressing subject matter, the author is persuasive in his clear and cogent writing. This book—and Cockburn’s reporting more generally—is helpful both to those with some familiarity with the region and total novices in deepening one’s understanding of a situation that defies adjectives.

As bombs were falling on Libya, Cockburn pointed out the jihadist nature of many of the rebel groups in the north African country, only to be confronted by an American reporter: “Just remember who the good guys are.” For those looking to avoid the Manichean oversimplifications we are too often fed, this book is a welcome and insightful reprieve.

In quotidianis disputationibus clarus

The indispensable Canadian disputationist David Warren wrote a piece mentioning Sudharma, the only newspaper printed in Sanskrit, the “dead” language of ancient India. It reminded me of the story of when someone asked Borges if he knew any Sanskrit. “Only the Sanskrit everyone knows,” was the Argentine’s response.

Anyway, given that there’s a daily newspaper in Sanskrit, Mr Warren thinks it would be entirely for the good that a daily newspaper be published in Latin.

Why not just publish a good newspaper in English, you ask? (After all, these are severely lacking or perhaps non-existent.) Not enough, Mr Warren argues:

An honest and rational account of what is happening in the world would have to be politically incorrect, in the extreme. People would be outraged, and the ACLU would move to suppress it right away. There would be protests, and attacks by Antifa; racism, misogyny, homophobia, would be alleged. The staff would not be safe to come to work.

Anyone caught reading it near a university would immediately be surrounded by shrieking harpies, and their careers in academia or elsewhere would end. Something like the #MeToo movement would be launched on Twitter, to root these people out.

Whereas, a newspaper in Latin would pass right under the progressive radar. Only those who could read Latin would take it, and almost all of them are mentally stable. Others would be trying to learn Latin, so they could also find out what is going on. Their efforts would contribute to the Catholic underground, where Latin use is spreading.

Expert Latinist Mons. Daniel Gallagher then took to the metaphorical presses of the same inprint to argue that:

Equidem desidero, potiusquam parvam sanitatis insulam, acta diurna praebere quae tot disceptationes ac disputationes provocent quot in lingua Latina, per linguam Latinam atque circa linguam Latinam provocatae sunt per saecula. Haec enim dirigam acta diurna non tantum ad principes verum etiam ad populum ipsum.

By which, in a manner of speaking, he meant:

Rather than offering “a little elitist island of sanity and spiritual calm,” I would want the paper to generate as much lively discussion and debate as always has and always will be generated in, around, and through Latin. I would want to aim the paper at the populus and not just the principes.

And Mr Warren then replies to the reply thus (in item the second).

Go and read all three; they make sound arguments.

II. A Brief to the People – by Mons. Daniel Gallagher (27.I.2019)

III. Two Items – by David Warren (29.I.2019)

Neo-Classical New York

The dome of the old Police Headquarters Centre Street in New York.

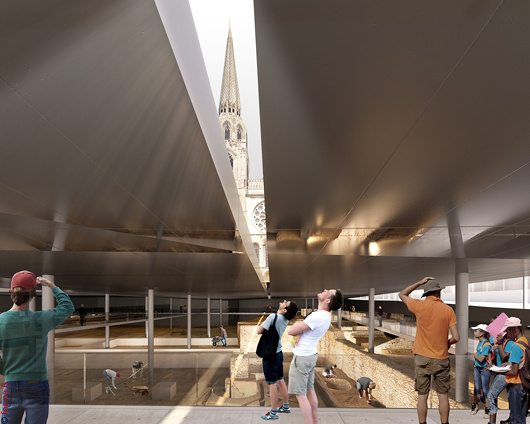

Chartres Disfigured

Plans for modern monstrosity in venerable cathedral’s forecourt

MORE BAD NEWS from Chartres. Fresh from the completion of a controversial and much criticised renovation of the ancient cathedral’s interior, le Salon Beige reports the city has unveiled plans to tear up the parvis in front of the cathedral and replace it with a modernist “interpretation centre”.

The original parvis (or forecourt) was much smaller than the one we know today. Between 1866 and 1905 the majority of the block of buildings in front of the cathedral, including most of the old Hôtel-Dieu, were demolished to give a wider view of the cathedral’s west façade and its “Royal Portals”.

After the war various plans to tart the place up were made and variously foundered — from a modest alignment of trees in the 1970s to Patrick Berger’s plan for an International Medieval Centre. More recently the gravelly space was unsuccessfully “improved” by the addition of boxes of shrubbery placed in a formation that, jarringly, fails to align with the portals of the cathedral.

The proposed “interpretation centre” designed by Michel Cantal-Dupart — at a projected cost of €23.5 million — destroys the gentle ascent to the cathedral and indeed reverses it. At a projected cost of €23.5 million, a giant slab juts apart as if displaced by an earthquake. The paying tourist is invited down into its infernal belly while others prat about on the slab’s upwardly angled roof, ideal for gawking at the newly commodified beauty of this medieval cathedral. It is practically designed for Instagramming, rather than reflection and contemplation.

As you would imagine, reaction has been strong. Michel Janva, writing at le Salon Beige, says the project “plans to imprison the cathedral” and “will disappoint not only pilgrims on their arrival, but also inhabitants and tourists”.

In the Tribune de l’Art, Didier Rykner is damning: “All this is purely and simply grotesque.” The sides of the centre, he points out, will be glazed to allow in natural light, but this will both interfere with multimedia displays and be bad for the conservation of fragile works of art. “This architecture, which looks vaguely like that of a parking lot, is frighteningly mediocre, and this in front of one of the most beautiful cathedrals of the world.”

Rykner attributes blame for the “megalomaniac and hollow project, expensive and stupid” at the doors of the mayor of Chartres, Jean-Pierre Gorges, who he argues has allowed much of the rest of the city’s artistic and architectural heritage to go to rot while devoting resources to this pharaonic endeavour.

Having walked from Paris to Chartres myself I can imagine how much this proposal will injure the experience for pilgrims. After three days on the road, to arrive at Chartres, stand in the parvis, and gaze up at this work of beauty, devotion, and love for the Blessed Virgin is a profound experience. If constructed, this plan would deprive at least a generation or two from having this experience. (But only a generation or two, for it is simply unimaginable to think this building will not be demolished in the fullness of time.)

Chartres is part of the patrimony of all Europe and one of the most important sites in the whole world. For it to be reduced to the plaything of some momentary mayor is a crime. With any luck, the good citizens of Chartres, of France, and of the world will put a stop to this monstrosity. (more…)

Happy New Year

The castle at Český Krumlov (or Krummau) in southern Bohemia, as photographed in winter by Libor Sváček.

Secret Splendor

by Andrew Cusack (Weekly Standard, 13 September 2010)

Paintings for the Catholic Church in the Dutch Republic

by Xander van Eck

Waanders, 368 pp., $100

This book is the first major overview and exploration of the art of the clandestine Roman Catholic churches in the Netherlands. It is not a study of paintings so much as a history in which art is like the evidence in a detective story, or perhaps even the characters in a play. It might seem extraordinary that there was a place for large-scale Catholic art during the Dutch Republic: Pre-Reformation churches had been confiscated and were being used for Calvinist services, while priests offered the Mass secretly in makeshift accommodations. Eventually a bargain between Dutch Catholics and the civil authorities emerged, trading Catholic nonprovocation in exchange for private toleration of the practice of the faith. Catholics began to purchase properties which, for all outward appearances, maintained the look of ordinary residences but whose interiors were transformed into resplendent chapels and churches.

Xander van Eck provides verbal portraits (often accompanied by contemporaneous painted ones) of several of the important clerics of the Dutch church during this period: Sasbout Vosmeer, the Delft priest influenced by St. Charles Borromeo; Philippus Rovenus, the vicar-apostolic who placed greater emphasis on clandestine parishes having specially dedicated churches, even while they kept an outward unecclesiastical appearance; and Leonardus Marius, the priest who promoted devotion to the 14th-century Eucharistic “Miracle of Amsterdam.” Marius was of such prominence that, after his death, shopkeepers rented out places on their awnings for punters to view his funeral procession. Van Eck includes a handful of amusing asides, such as the expulsion of the Jesuits from the Netherlands as a result of their constant discord with the secular clergy. Mass continued to be offered at the Jesuit church of De Krijtberg in Amsterdam “in the profoundest secrecy” — thus creating a clandestine church within a clandestine church!

The role of the clergy in sustaining the Dutch Church is unsurprising, but it is instructive to learn how instrumental laity were to keeping alive the light of Catholic faith in the Netherlands at the time. Clandestine churches relied on the generosity of Catholic families. Prominent families often provided their own kin as consecrated virgins who brought large dowries into the church, or as priests with suitable inheritances to maintain or endow clandestine parishes. The clandestine church of ’t Hart in Amsterdam, built by the merchant Jan Hartman for his son studying for the priesthood, is still open today as the Amstelkring Museum and Chapel of “Our Lord in the Attic.”

While van Eck explores the extent to which Dutch art from the period followed European norms, an emphasis on the particularity of the art of the clandestine church is to be expected. The sheer volume of art produced during this period — for just three Amsterdam churches alone there were 16 altarpieces — is partly explained by the phenomenon of “rotating altarpieces.” The paintings above the altar would be changed according to the feast or season — a practice sometimes seen in Flanders or parts of Germany but never nearly so widespread as in the Netherlands proper.

Constrained as clandestine churches were on the narrow plots typical of Dutch cities, there was no room for side chapels that might include the large funerary monuments prominent families would construct. This left altarpieces as the most convenient way for munificent Catholics to provide art for their churches: Rotating the altarpieces provided a handy way of displaying numerous commissions rather than just the donation of whoever had been generous most recently, and the themes of these commissions tended to vary in appropriateness to different feasts and seasons.

Some found fault with this method: Jean-Baptiste Descamps, visiting Antwerp in 1769, complained that the most interesting altarpieces were not permanently displayed and were more likely to be damaged in the process of being moved so often.

While the accomplishment and ingenuity of Dutch Catholics in keeping their faith during the Republic was striking, the ill-defined administrative structure of the persecuted church allowed conflicts between clerics to thrive, and doctrinal disputes emerged and festered. The disputes over Jansenism that swept over France and the Netherlands, for example, only exacerbated the administrative problems of the clandestine church. Like their Calvinist compatriots, the Jansenists tended to frown on indulgences, the veneration of saints, recital of the rosary, and private acts of worship, putting greater emphasis on the Scriptures and a more rigorous asceticism. As van Eck points out, this difference in emphasis was not exclusive to the Jansenists, but their novelty (and their heresy) was in preaching the exclusivity of their approach above all others.

Numerous vicars-apostolic had written to Rome arguing for the re-establishment of the episcopacy in the Netherlands to solve the disputes over authority, but their appeals fell on deaf ears. In 1723 a large portion of the Jansenist clergy reinstituted the episcopacy by electing an archbishop of Utrecht from their number — and were subsequently excommunicated, splitting the clandestine church and its clergy in two. (This excommunicated rump united with the opponents of papal infallibility in the following century to form a body that still calls itself the Old Catholic Church.)

When one looks at all this glorious art, not to mention the lives and pious ingenuity of the persecuted, it’s difficult not to feel a little poorer, considering the fruits of our churches in an ostensibly free era. Why does the church today commission painters who are either mediocre or trendy — or both? Artists like Hans Laagland and Leonard Porter show that good art — good liturgical art, even — is possible today, but commissions from the church for traditional artists are sadly few.

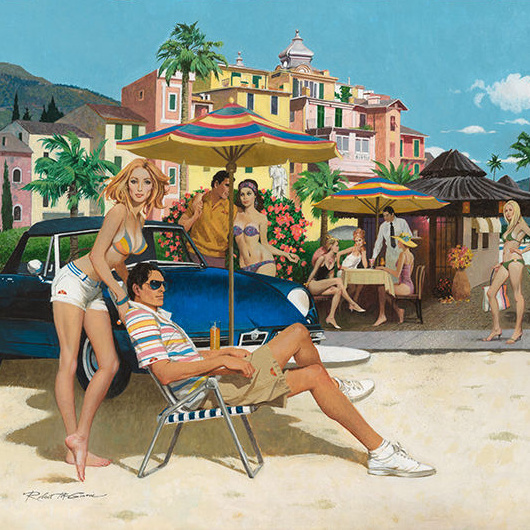

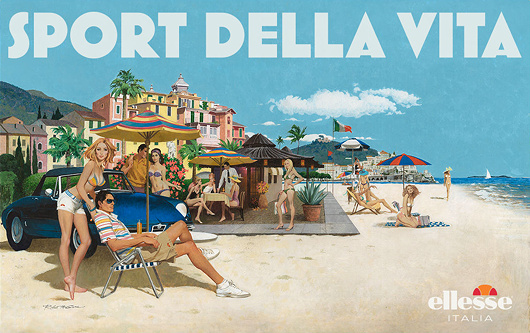

That Sixties/Seventies Style

Robert McGinnis for Ellesse

Italian clothing company Ellesse hired Robert McGinnis — illustrator of over 1,200 paperback covers and several James Bond movie posters — to do four paintings for their 2011 spring/summer advertising campaign.

Ellesse was founded in 1959 by Leonardo Servadio — L.S. — and became known for combining functional sportswear with a sense of fashion. The firm was purchased by Britain’s Pentland Group in 1994, and it’s Pentland’s ad team that commissioned McGinnis to come up with these retro ad designs.

McGinnis’s work here feels strangely up-to-date and yet nostalgic without any particular contradiction. Still, one half expects Sean Connery to strut cheekily into view.

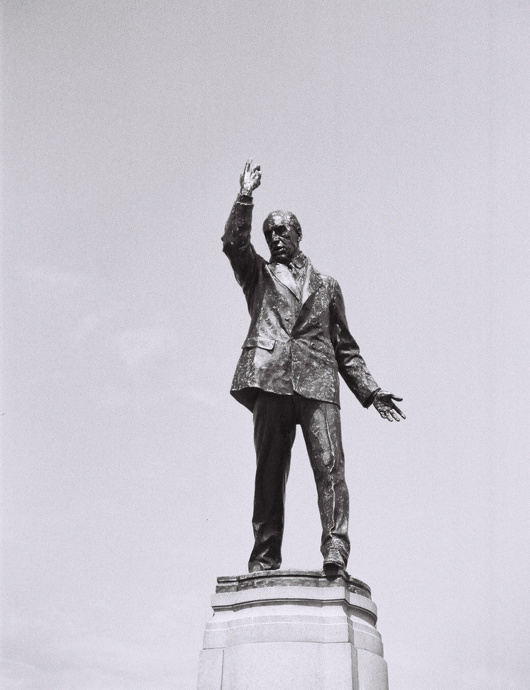

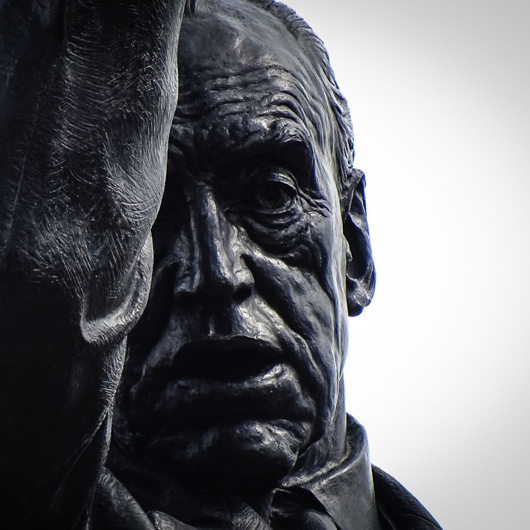

Carson at Stormont

Few statues in Ireland are as dramatic as that of Edward Carson at Stormont. The unionist leader is depicted in amidst an oratorical flourish, doubtless in one of his speeches to mass meetings condemning home rule.

In the 1910s as the rebirth of an Irish parliament looked more likely, Carson took up the cause of fighting home rule on behalf of Ireland’s large Protestant minority who feared Catholic domination. When the anti-home rulers realised the cause was losing, they retreated from Irish unionism to Ulster unionism. If home rule was to be granted, Ulster must be exempted. In the end this meant home rule was granted to a parliament covering two-thirds of the Irish province of Ulster — six counties that would henceforth be known as Northern Ireland.

“His larger than life-size statue,” one historian wrote, “erected in his own lifetime in front of the Northern Ireland parliament at Stormont, symbolizes the widely held perception that Northern Ireland is Carson’s creation.”

This is of course the great irony, given that Edward Carson was a Dublin boy through and through. While instrumental in ensuring northeastern Ireland’s exemption from an Irish parliament, Carson actually had little to do with the entity thereby created. When offered the premiership of Northern Ireland he declined it on the grounds of having no real connection with the place.

Craig, not Carson, is the true father of Northern Ireland; he imbued the new statelet with a sense of bigotry and tribal hatred that Carson lacked. The Dubliner urged Ulster’s new leaders to treat the province’s Catholics well.

“We used to say that we could not trust an Irish parliament in Dublin to do justice to the Protestant minority,” Carson said. “Let us take care that that reproach can no longer be made against your parliament, and from the outset let them see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from a Protestant majority.”

Alas, it became apparent to Carson that discrimination and inequality were becoming in-built within Northern Ireland’s government, from the Parliament at Stormont down to the lowest forms of local government. He confided to a Catholic friend in London that rather than being an integral part of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland was turning into “a second-class dominion”.

After partition Carson was created a British judge and accordingly ennobled. (Disappointingly the plaque on his Dublin birthplace next to Conradh na Gaeilge refers to him by the incorrect style of ‘Lord Edward Carson’.) He settled at Clever Court near Minster-in-Thanet, Kent, and never lived in his native Ireland again.

Nonetheless he was held in awe and reverence by the Protestant Unionists of Ulster, who commissioned the striking statue by Leonard Stanford Merrifield that stands in front of Parliament Buildings, Stormont — now home to the Northern Ireland Assembly. It was unveiled by Craig, by then ennobled as Lord Craigavon, while Carson was alive and present in July 1932, joined by a crowd of 40,000 well-wishers.

Carson died in 1935 and was given the rare honour of a state funeral. HMS Broke brought his Union-Jack-draped coffin back to Ireland — albeit to Belfast — and he was interred in the Anglican Cathedral of St Anne. Northern Ireland claimed him even in his final burial: soil from each of its six counties was scattered on his coffin when laid to rest in the tomb.

Still his statue stands at Stormont, gesturing stridently as if to challenge an entire province — a province he by his own description had little to do with. Calls for it to be removed emanate occasionally from typically boring quarters and have so far been rebuffed — wisely. Carson, unlike many of those who cherished his memory, was an honourable man, and it is a pity it took so long for the Protestants of Ulster to heed the advice of their confrère from Dublin.

Soho Iridescent

Stiff & Trevillion’s 40 Beak Street in London

Beak Street in London is teeming with turquoise iridescence since the completion of a new office building by the architectural firm of Stiff & Trevillion earlier this year. A joint project between property investment companies Landcap and Enstar, Number 40 Beak Street has been purchased for £40 million by Damien Hirst — the canny businessman who sells dead animals in formaldehyde glass boxes. The over-27,000-square-foot building will serve as the primary London studio for Hirst and headquarters for his company, Science (UK) Ltd, in addition to housing a restaurant at ground level.

Five storeys tall, 40 Beak Street features a number of roof terraces in addition to cornice work designed by Hertfordshire-based artist Lee Simmons. The glazed bricks — “hand dipped” the architects tell us — make for a welcome change from the omnipresence of metal and glass on one end of the spectrum and cheap monotone brick on the other.

The PR hype makes much of bringing a bit of artistic and creative edge back into Soho, a neighbourhood whose final glory days have been depicted in a much-praised book by the Telegraph’s Christopher Howse. We’re not so sure.

Hype aside, 40 Beak Street is an excellent addition to the London landscape and the designers are to be commended for their fine eye for detail. Someone at Stiff & Trevillion knows what they’re doing.

Around

“By contrast, Hungary’s 100,000 Jews—a larger presence relative to the country’s population of 8 million—walk unmolested to synagogue in traditional Jewish costume and hold street fairs with minimal security presence.” The Real Modern Anti-Semitism

No American writer has wielded such influence, John Rossi writes. So why is he so little known today? The Strange Death of H.L. Mencken

Damon Searl on Uwe Johnson: The Hardest Book I’ve Ever Translated.

Then there are the mythical and miraculous islands of the medieval Atlantic

120 years after the Spanish-American War, here are five books to help you better understand American imperialism.

The always-worth-reading Michael Brendan Dougherty explores what the Catholic traditionalists of the 1960s and 1970s were thinking. (More people, however, are talking about his look at Francis’s record as pope.)

In Manhattan, John Massengale suggests there are better ways to get around town.

Argentina’s most beloved bibliophile Alberto Manguel on the great books that are now lost to history.

In Hungary, like everywhere else, people are marrying later, with demographic consequences. Or is this changing? The country is not just experiencing a fertility spike, Lyman Stone reports. Hungary is winding back the clock on much of the fertility and family-structure transition that demographers have long considered inevitable. Is Hungary Experiencing a Policy-Induced Baby Boom?

Speaking of which, from the same author, what about Poland’s Baby Bump?

Meanwhile in New England, an entitled Harvard academic pulls rank on the mother and child living in an affordable unit in their apartment building in a telling tale of class and hierarchy in America.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Image: © HughJLF

Image: © HughJLF Image: © Stephen Benton

Image: © Stephen Benton Image: © Stephen Benton

Image: © Stephen Benton