Arts & Culture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Abbott’s Gun

Berenice Abbott took a few photographs of New York’s old Police Headquarters viewed from one of the gunsmiths across Centre Market Place.

This street behind the NYPD HQ (which fronts on to Centre Street) became the gunsmiths’ district of Manhattan — policemen being one of the best customers for many of these businesses. (Criminals being another.)

There is something almost mediæval about the giant gun hanging outside, advertising to one and all what the shop had to offer.

Frank Lava, the gunsmith photographed, shut decades ago, but the John Jovino Gun Shop was originally next door before moving around the corner into Grand Street.

Like Lava’s, Jovino’s continued the tradition of hanging a giant gun outside the shop like in Abbott’s photograph.

The John Jovino Gun Shop, founded 1911, chucked in the towel last year when “Gun King Charlie” — owner Charlie Yu — decided the rent was too damn high.

A Metropolitan Christmas

I suppose Whit Stillman’s ‘Metropolitan’ is not strictly speaking a Christmas film but Yuletide is as good a time as any to watch the most Upper-East-Side movie ever to make the silver screen.

It includes a scene (clip above) from the Service of Nine Lessons and Carols at St Thomas, Fifth Avenue, which to my mind is the best carol service in New York. It’s even better when followed by a few drinks at the University Club one block up.

St Birinus

Staying with friends in Oxford a few weeks ago meant that Sunday Mass was heard at the church of St Birinus in Dorchester-on-Thames.

This church was built in 1849 by the local Davey family and dedicated to the priest who converted the king and people of Wessex whose relics were venerated at Dorchester Abbey.

For more than the past quarter-century St Birinus has been restored and improved by the parish priest, Fr John Osman. Mass is offered here with great reverence, and accompanied by excellent music. They are currently raising money for a new organ.

Auspiciously the architectural historian Michael Hodges wrote an article about the church in the October 2021 Catholic Herald.

St Birinus is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful village Catholic churches in all England. It is a visual feast best experienced in the flesh.

From Buda towards Pest

A 1959 view from the Vienna gate of Budapest’s Castle district

Taken in 1959, a photograph in the Fortepan archive shows two girls standing on the stone bench of the Vienna Gate — rebuilt in 1936 to mark the two-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of Buda’s liberation from the Ottomans.

Hungary’s domed neogothic Parliament Building sits in Pest on the opposite bank of the Danube in the distance, with the baroque spire of the Church of the Wounds of St Francis nearer on the Buda side of the river.

Sadly, this fine view can no longer be seen: the trees in the park below the Bastion promenade have been allowed to grow too tall. A somewhat superfluous flagpole bears the banner of Budapest’s 1st District.

The Hungarian government has invested a great deal of care and attention (not to mention investment) to the Castle quarter in recent years, so perhaps restoring this view could be added to their to-do list.

London Visitors

1874, oil on canvas, 63 x 45 in.

Happily, the Tudor-era uniforms are still in use there and are the hallmark of the school to this day.

The visiting couple are obviously in from the provinces, and the woman gazes daringly at the viewer.

I wonder if the cigar on the steps was left for a moment by the artist as he dashed to take this snapshot.

The threat to Bevis Marks

The Spanish & Portuguese synagogue at Bevis Marks in the City of London is well worth a visit. The last time my parents were in town we went for a tour given by an ebullient guide who was a big fan of Ben Disraeli and who taught us the story of the congregation and the building.

In Apollo magazine, Sharman Kadish has written a good summary of the ongoing threat to Bevis Marks from proposed overbearing office developments. (Dr Kadish also wrote a 2004 article on “The ‘Cathedral Synagogues’ of England” in Jewish Historical Studies.)

One planning application which would have almost completely cut off the synagogue’s natural light has been rejected but others loom on the horizon, one recommended for approval by the City’s planning czars.

London blog ‘Ian Visits’ visited Bevis Marks in 2019.

The synagogue is now temporarily closed to visitors for renovations but shabbat services continue to take place. Visiting information otherwise can be found on the congregation’s website.

Incidentally — given that November is the month of the dead — the name carved above the entrance of the synagogue is Kahal Kadosh Sha’ar ha-Shamayim, or ‘Holy Congregation of the Gates of Heaven’ which mirrors the Catholic cemetery where two of my grandparents are buried. (more…)

Yellowfin

Flying blind by seeing a play you have no idea about and haven’t read up on is obviously a game of chance, but accompanying two mates to see Marek Horn’s new play ‘Yellowfin’ at Southwark Playhouse last night was an unexpected and thoroughly enjoyable delight.

It might just be me, but if I had been told the play was about three U.S. senators interrogating a smuggler of illegal fish substances I would have turned off completely and missed this winner.

Set in the familiar but not-too-distant future, ‘Yellowfin’ is a slow-release capsule of a not-terribly-fussed world following an inexplicable ecological disaster that, as it happens, turns out to be perfectly manageable.

It takes long and confident strides veering towards nihilism without quite touching it but the real joy is its almost-titillating scepticism of the eco-reorganisationalism that is all the rage now.

If nothing else, ‘Yellowfin’ is a deeply subversive play.

Production Photos: Helen Maybanks

Nancy Crane masters the role of the committee chairwoman whose intelligence never quite matches her confidence. Beside her is Beruce Khan as the smug younger colleague.

Nicholas Day supplies delicious nuggets of comic relief as an elderly senator not entirely sure of his surroundings. (Parallels to the most recent U.S. Senate alum to move into the White House are tempting.)

Joshua James is the fish-smuggling object of their inquiry who breezily pops the bubble of sententious seriousness the senators attempt to bring to the matter at hand.

Good writing, well acted. Let the record show ‘Yellowfin’ is well worth it.

Production Photos: Helen Maybanks

Gut Wulfshagen

I love when a house is arranged with its farm buildings around a garth or a gaard or a hof.

At Gut Wolfshagen in Schleswig-Holstein the barns are arranged flanking a narrow pinch that gives just a hint of the manor house beyond, lending an air of baroque surprise.

This house was built by Andreas Pauli von Liliencron at the very end of the seventeenth century and was acquired by the von Qualen family in 1787.

When the last of the von Qualens here died childless in 1903 they bequeathed Gut Wulfshagen to the uxorial nephew Ludwig Graf zu Reventlow. (more…)

A Dwiggins Roundup

WE LOVE FEW things more than a talent rediscovered after decades of neglect, and in the realms of graphic design no one fits this bill better than William Addison Dwiggins (1880-1956).

This man was a type designer, calligrapher, illustrator, book designer, and commercial artist with a good eye and just the right level of whimsy.

Much of the revival of interest is thanks to Bruce Kennett and his book W. A. Dwiggins: A Life in Design which has done a great deal to spread the gospel of Dwiggins.

Here below are a series of links about the man and his work. (more…)

Northern Neogothic

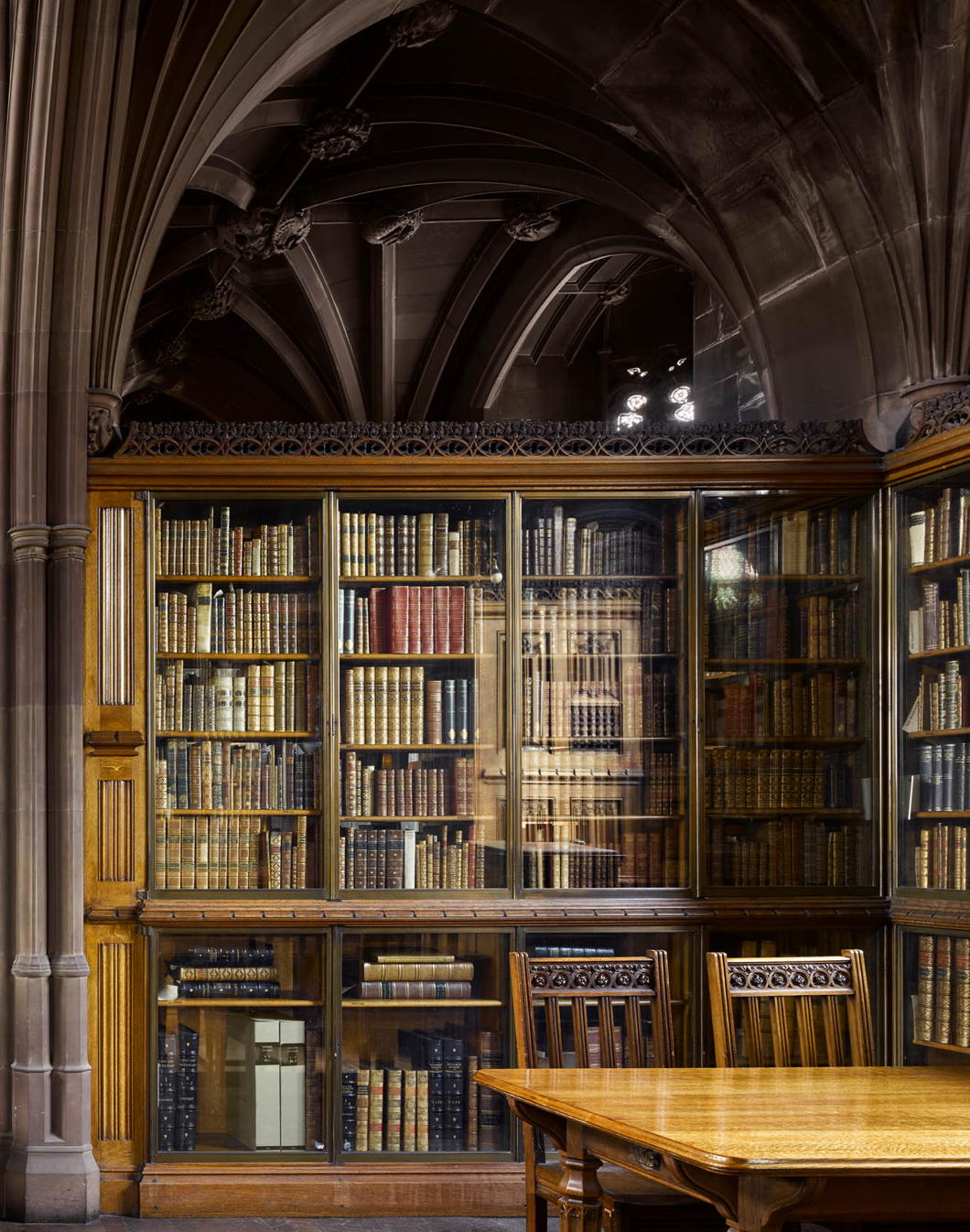

Will Pryce’s Photographs of the John Rylands Library

Will Pryce is one of the best architectural photographers out there and Country Life put him to good use for an article earlier this year about Manchester’s John Rylands Library.

The library was founded by the deliciously named Enriqueta Rylands in memory of her late husband, the merchant philanthropist John Rylands who became Manchester’s first multi-millionaire.

Manchester experienced a flowering of northern neogothicism in the nineteenth century, and the John Rylands Library is sometimes used as a film location standing in for Pugin’s Palace of Westminster, most recently in the 2017 film ‘Darkest Hour’. The city’s magnificent Town Hall fulfils this role even more often — c.f. the UK telly original of ‘House of Cards’. Scandalously, Manchester’s City Council no longer meet in their original council chamber, having decamped to the nonetheless handsome 1938 extension built next to it.

The John Rylands Library (and research institute) is here to stay though.

For more of Pryce’s work, see his website.

What Huxley’s Got on Orwell

Comparing dystopic visions of the English twentieth century

by ALEXANDER FRANCIS SHAW

Aldous Huxley wasn’t as good a writer as George Orwell but in several ways his Brave New World exceeds the prescience of 1984.

Huxley understood how society would respond if the laws of human ecology were to change. In a mechanised age, useless activity would become a necessity, while medical revolution and sexual deregulation in turn become the germ of totalitarianism. Orwell and just about everyone else since have had the opposite idea – that the libertines would be the liberators – and the fever-pitch of this very delusion forms the central tenet of Huxley’s dystopia.

Both visionaries describe state censorship, but in Huxley’s Brave New World one recognises eery pre-echoes of ‘Woke culture’ in an opiate-addled society which has to conceal its operational ethos from its own general consciousness in order to keep itself functioning smoothly.

With Orwell – the human struggle is represented as Man versus The State. Huxley recognised, as we are now encouraged not to, that society is the product of biology and, provided that people’s biology can be conditioned correctly, the state can foster grass-roots totalitarianism without the use violent coercion.

Neither dystopia has been fully realised – but in Orwell’s case this has been because progress has provided its own remedies (nobody could have imagined in the 1940s that telescreens would also be a conduit of private interaction for dissenters’ online discourse). One gets an unsettling feeling that Huxley’s medical dystopia is still developing in 2021 with no solutions in sight.

Rather than solve the riddle of human happiness, the citizens of Brave New World condemn those who fail to gloss over their displeasure with life through the mollifying comforts of sex and tranquillisers. Science becomes a branch of pragmatism, wielded by social engineers who can no more observe their own fields than look at their own eyeballs.

We are left with the question of how an outsider, possessed of higher directives than his own hedonism, might react to such a society?

Huxley answers this by introducing a Linda and her son, John, who live in a ‘savage reservation’ where medical advances have not been imposed. Traditional sexual morality is thus observed by the occupants along with – shudder! – family life and religious practices and other pursuits which lend meaning to their backward lives.

Linda arrived in the reservation by accident, having been born and acculturated in the ‘civilised world.’ She teaches her son how to read, but brings them both into disgrace with her promiscuity, so that John retreats into the comforts of a book which happens to be ‘The Complete Works of William Shakespeare.’ In Shakespeare, John finds the words that enable him to assert himself both on the reservation and – to the curiosity of his minders – when he finally returns to civilisation.

I sense that Orwell would have furnished John with a lowlier reference-point to human nobility and driven the same points home more poignantly with a dog-eared copy of Paris Match. But, as I said, Huxley was a better visionary than he was a wordsmith.

Once in the ‘civilised world’ John falls in love and faces a problem which, less than a century after Huxley’s work was published, defines what is perceived as a ‘crisis of masculinity’: how to court a woman who gives herself out to dozens of men regardless of merit. Unable to disabuse himself of his chivalric values – and unwilling to accept her worthless sexuality when she freely offers herself to him – John becomes what we would now call a proto-“incel” and dies, as the carnal realists of the toxic chatrooms might anticipate, on the end of a rope.

Smokescreens of happiness and delusion are maintained with a tranquilliser called Soma. Much as anti-depressants are a major feature of modernity – their use strongly suggesting that they are employed where artificial economies and casual sex are normalised – one senses that we have not yet perfected the Brave New World’s capacity for total bafflement. Nor has any welfare state or medical advancement completely collectivised the process of raising children.

This tranquillised social order is upheld by World Controller Mustapha Mond, Huxley’s benign analogue to Orwell’s Big Brother and on that account one of the few people in this dystopia who has achieved any kind of true satisfaction himself. Mond’s discourses bring Huxley to the place of scientific observation in the stable technological order:

‘once you start admitting explanations in terms of purpose – well, you don’t know what the result might be…’

In other words: Heaven forbid anyone should question the dogmas of settled science.

In terms of who may be allowed to see through the delusion, Mond likens the social hierarchy to an iceberg – with 10 per cent above the surface and 90 per cent below. Maverick, enquiring minds must either be sent to isolated communities or – like himself – shoulder the burden of everyone else’s delusion.

Despite Orwell’s predictions of people cowering under state tyranny and violence, Huxley’s work remains the creepier for its ability to get under the skin of the liberal society that we find familiar.

How much worse is it to read of a dystopia in which, by our own liberated will, we are complicit?

The old Dutch houses of the Cape

From Here There and Everywhere (1921) by Lord Frederic Hamilton:

THESE OLD DUTCH HOUSES are a constant puzzle to me. In most new countries the original white settlers content themselves with the most primitive kind of dwelling, for where there is so much work to be done the ornamental yields place to the necessary; but here, at the very extremity of the African continent, the Dutch pioneers created for themselves elaborate houses with admirable architectural details, houses recalling in some ways the chateaux of the Low Countries.

Where did they get the architects to design these buildings? Where did they find the trained craftsmen to execute the architects’ designs? Why did the settlers, struggling with the difficulties of an untamed wilderness, require such large and ornate dwellings? I have never heard any satisfactory answers to these questions.

Groot Constantia, originally the home of Simon Van der Stel, now the government wine-farm, and Morgenster, the home of Mrs. Van der Byl, would be beautiful buildings anywhere, but considering that they were both erected in the seventeenth century, in a land just emerging from barbarism seven thousand miles away from Europe, a land, too, where trained workmen must have been impossible to find, the very fact of their ever having come into existence at all leaves me in bewilderment.

These Colonial houses, most admirably adapted to a warm climate, correspond to nothing in Holland, or even in Java. They are nearly all built in the shape of an H, either standing upright or lying on its side, the connecting bar of the H being occupied by the dining-room. They all stand on stoeps or raised terraces; they are always one-storied and thatched, and owe much of their effect to their gables, their many-paned, teak-framed windows, and their solid teak outside shutters. Their white-washed, gabled fronts are ornamented with pilasters and decorative plaster-work, and these dignified, perfectly proportioned buildings seem in absolute harmony with their surroundings.

Still I cannot understand how they got erected, or why the original Dutch pioneers chose to house themselves in such lordly fashion. At Groot Constantia, which still retains its original furniture, the rooms are paved with black and white marble, and contain a wealth of great cabinets of the familiar Dutch type, of ebony mounted with silver, of stinkwood and brass, of oak and steel; one might be gazing at a Dutch interior by Jan Van de Meer, or by Peter de Hoogh, instead of at a room looking on to the Indian Ocean, and only eight miles distant from the Cape of Good Hope.

How did these elaborate works of art come there? The local legend is that they were copied by slave labour from imported Dutch models, but I cannot believe that untrained Hottentots can ever have developed the craftsmanship and skill necessary to produce these fine pieces of furniture.

I think it far more likely to be due to the influx of French Huguenot refugees in 1689, the Edict of Nantes having been revoked in 1685, the same year in which Simon Van der Stel began to build Groot Constantia. Wherever these French Huguenots settled they brought civilisation in their train, and proved a blessing to the country of their adoption. […]

Here, at the far-off Cape, the Huguenots settled in the valleys of the Drakenstein, of the Hottentot’s Holland, and at French Hoek; and they made the wilderness blossom, and transformed its barren spaces into smiling wheatfields and oak-shaded vineyards. They incidentally introduced the dialect of Dutch known as “The Taal,” for when the speaking of Dutch was made compulsory for them, they evolved a simplified form of the language more adapted to their French tongues.

I suspect, too, that the artistic impulse which produced the dignified Colonial houses, and built so beautiful a town as Stellenbosch (a name with most painful associations for many military officers whose memories go back twenty years ) must have come from the French.

Stellenbosch, with its two-hundred-year-old houses, their fronts rich with elaborate plaster scroll-work, all its streets shaded with avenues of giant oaks and watered by two clear streams, is such an inexplicable town to find in a new country, for it might have hundreds of years of tradition behind it!

Wherever they may have got it from, the artistic instinct of the old Cape Dutch is undeniable, for a hundred years after Van der Stel’s time they imported the French architect Thibault and the Dutch sculptor Anton Anreith. To Anreith is due the splendid sculptured pediment over the Constantia wine-house illustrating the stoiy of Ganymede, and all Thibault’s buildings have great distinction.

But still, being where they are, they are a perpetual surprise, for in a new country one does not expect such a high level of artistic achievement.

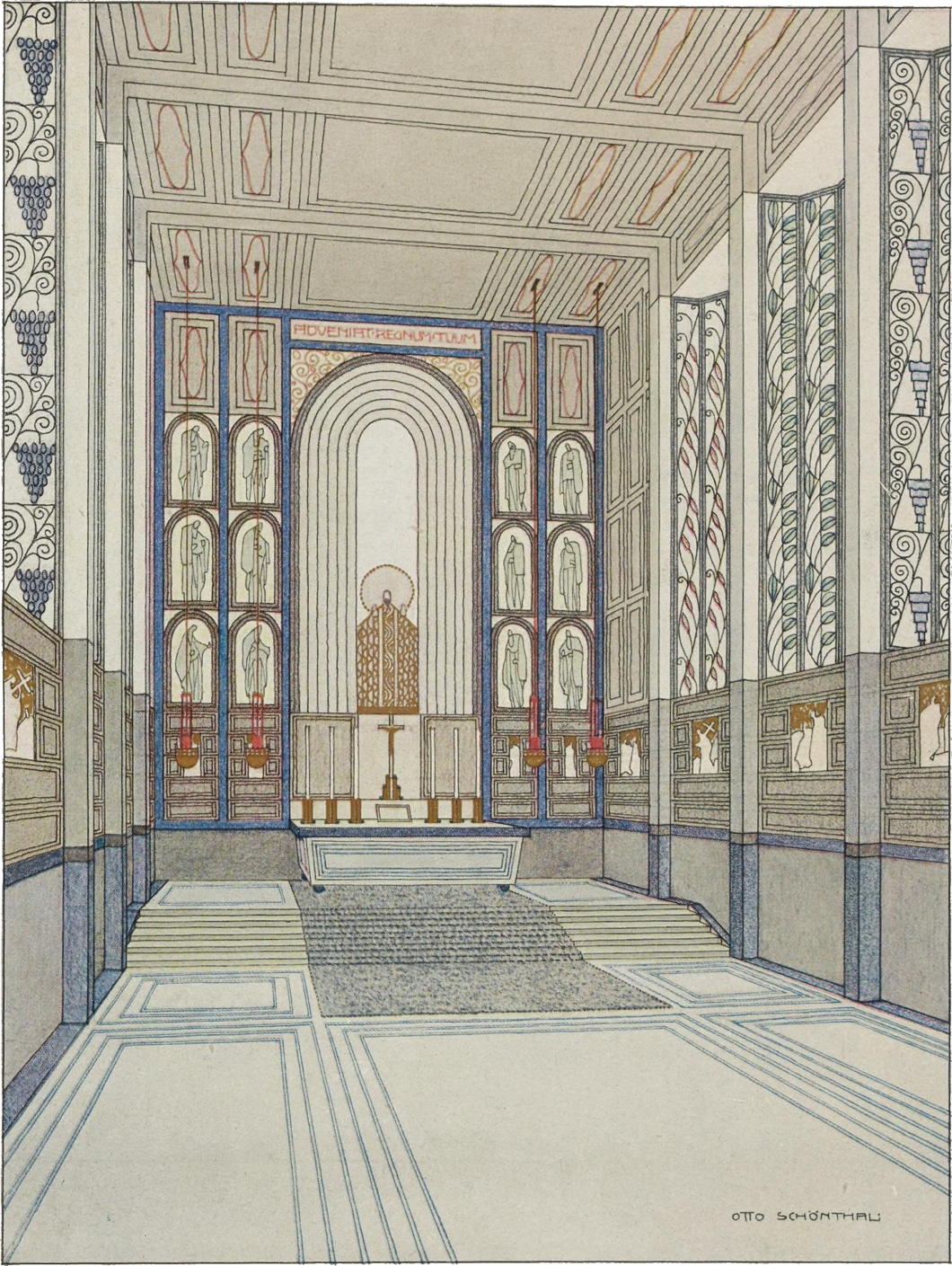

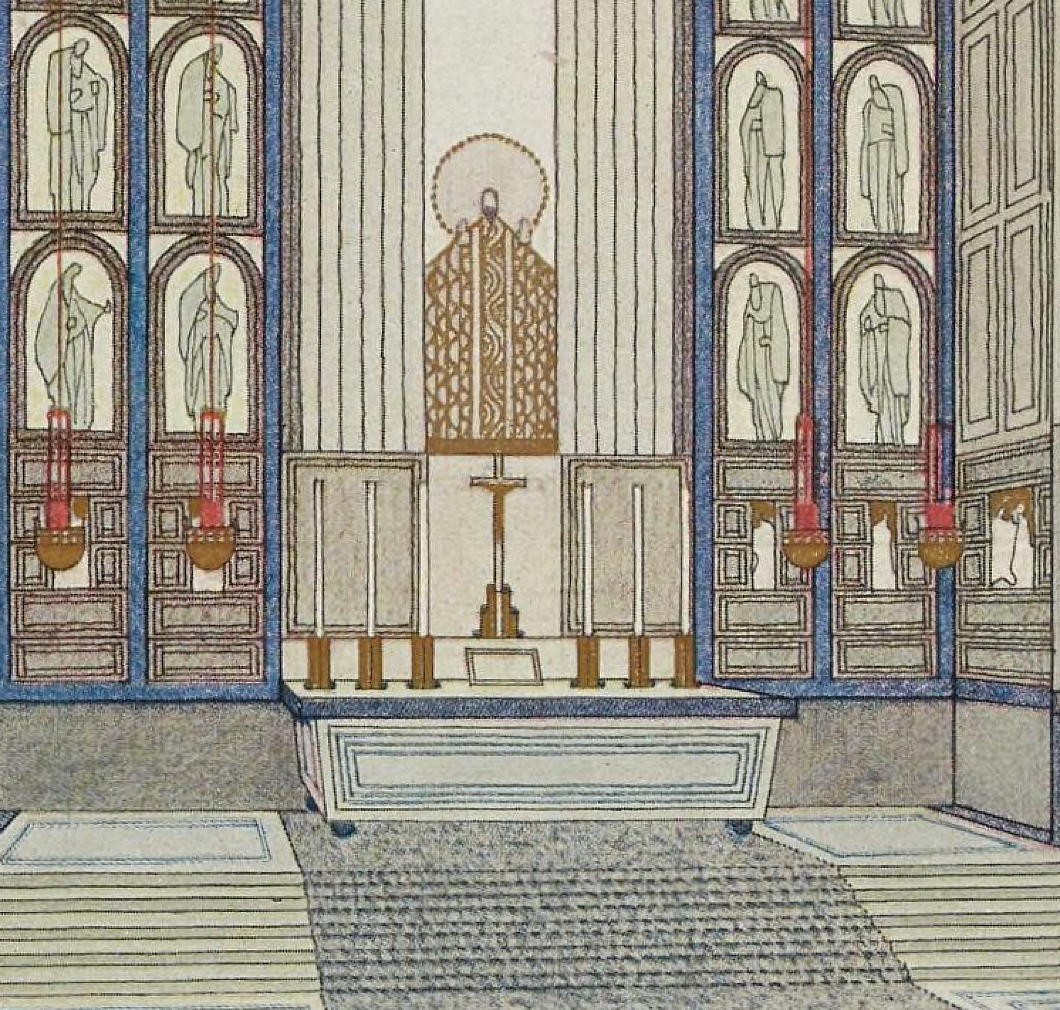

The Other Modern: Otto Schöntal

The Viennese architect Otto Schöntal was a student of Otto Wagner at the Academy of Fine Arts and exhibited this project for a Schloßkapelle in the periodical Moderne Bauformen in 1908.

It combines a simplicity of form with greater complexity in its decoration but like the work of many of the more mid-ranking architects of the Secession it comes across as a bit rigid and angular despite a certain freeness in its design.

A rood-stair pulpit

Among the features of the Church of All Saints in the Forest of Dean village of Staunton, Gloucestershire, is this fifteenth-century stone pulpit.

It is built into a rood-stair that once led to a wooden rood loft, demolished and removed some centuries ago.

This church also has a Norman font thought to have been hollowed out of an earlier square pagan Roman altar.

Pentonville Expressionism

When partner James Beazer of architectural firm Urban Mesh wanted to build an extension onto his Pentonville townhouse his tenderness towards brick expressionism took physical form.

“I love the work of the German Expressionists,” Beazer told the FT. “The playfulness of their use of brick. I think we’ve become uncomfortable with decoration today. Perhaps property has become too valuable. If it wasn’t, we’d all feel more able to take risks.”

Bringing brick expressionism down to a smaller scale produces interesting results here in Beazer’s case. It’s fun and somewhat slapdash — all the unconcerned confidence of an amateur delivered by a professional in his back garden. Hamburg meets the Shire in Islington.

I would have gently arched the windows, however, and the choice of lighting fixture is mundane. But it is a fundamental Cusackian principle never to let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

“I would probably have struggled to convince a client to do it,” Beazer says. But he has no confidence in the twisted brick add-on’s future once he moves house. “To be honest, the next people who move in will probably flatten it and replace it with a huge glass extension.”

The late Gavin Stamp gave an excellent lecture under the auspices of the Twentieth Century Society entitled ‘Hanseatic visions: brick architecture in northern Europe in the early twentieth century’.

It had been available online but now, alas, seems to be lost in the mists of time since the new incarnation of the Society’s website went up. Hope they stick it back online soon.

Het Spui

Amsterdam is known for its canals, not its public squares, but Het Spui is quite welcoming all the same. The name means roughly sluice or floodgate, pointing to the unsurprisingly watery origins of the place.

At first, it was a canal like any other and was only filled in during the nineteenth century: The first part in 1867 when the neighbouring Nieuwezijds Achterburgwal was filled in, the rest in 1882, two years before the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal.

The Spui (pronounced “spouw” — unless Dawie van die bliksem corrects me) is a focal point surrounded by a number of sights. There’s the Old Lutheran Church, where the Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen met in its early years and still a working congregation today.

There’s the Maagdenhuis, built as a Catholic orphanage and also the seat of the Archpriest of Holland and Zeeland until the restoration of the hierarchy in 1856. The orphanage moved out in 1957 when the building became a bank branch but was purchased by the University of Amsterdam in 1962 to house the administration of the growing institution. (more…)

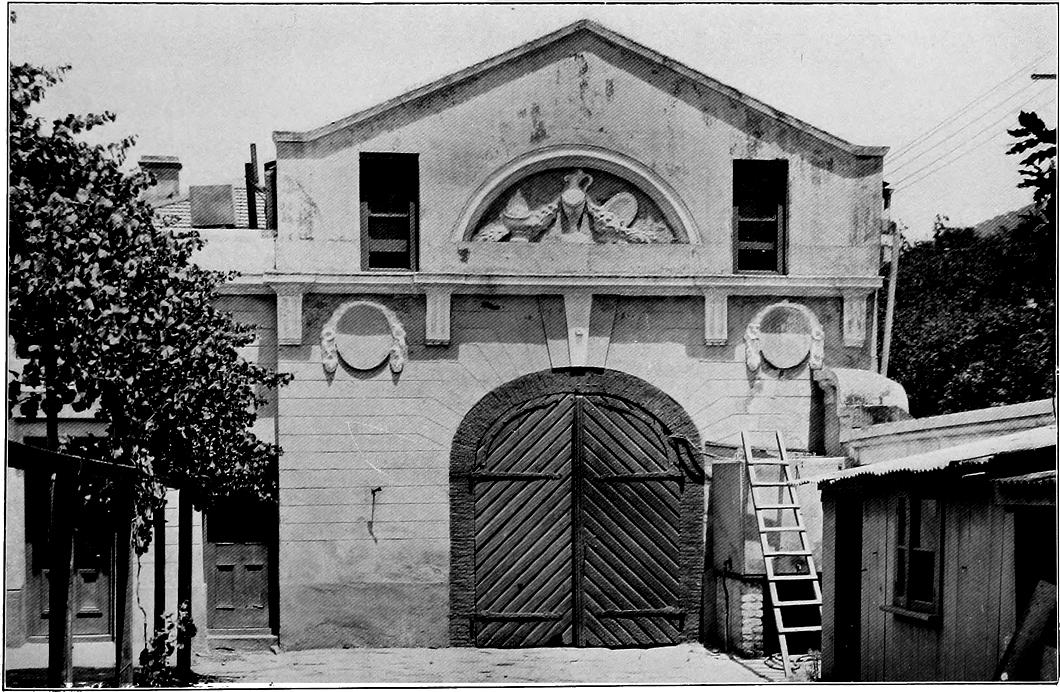

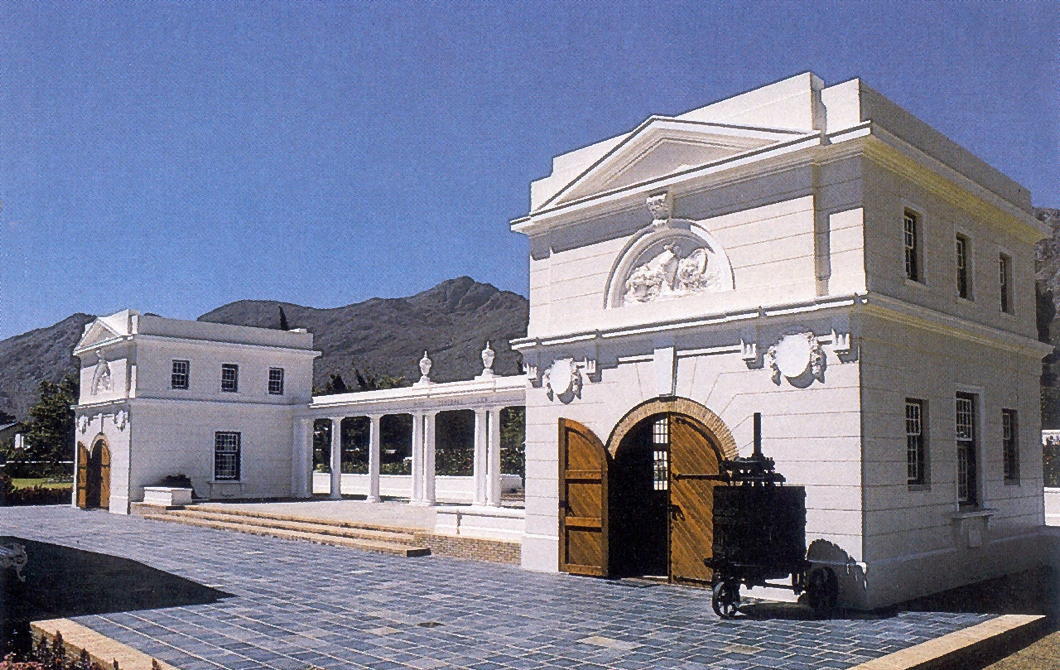

The Perfect Home Garage

The Coach-House at Saasveld, Cape Town

With all of Suburbia working from impromptu home offices set up in their garages during Covidtide — presumably clinging to their space heaters at this time of year — the subject of the residential garage came up in conversation.

America, being a land of plenty, has the very worst and the very best of home garages. The best are, if a separate structure, often in an arts-and-crafts style and ideally with a floor above perfect for extra storage, conversion to a rental unit, or space for disgruntled teenagers. If attached to the house itself, it is to the side, and only one storey, so as not to distract attention.

The worst, however, are double wide and take up most of the facade, as well documented by McMansion Hell.

My perfect residential garage, however, is not in the States but from the Western Cape. Saasveld was the home of Baron William Ferdinand van Reede van Oudtshoorn, also 8th Baron Hunsdon in the Peerage of England.

In the 1790s, the Baron built the house on his Cape Town estate — between today’s Mount Nelson Hotel and the Laerskool Jan van Riebeeck. The elegant house and outbuildings were almost certainly the work of Louis Michel Thibault, the greatest architect of the Cape Classical style.

Behind the house were two flanking wine cellars linked by a colonnade, at least one of which (above) was eventually put to use as a coach house or garage and photographed by Arthur Elliott.

Unfortunately the house and its grounds fell into ruin and the Dutch Reformed Church bought the site for development and decided to demolish Saasveld. Architectural elements from the house were preserved and eventually re-assembled at Franschhoek where a reconstructed Saasveld serves as the Huguenot Memorial Museum today.

As Mijnheer van der Galiën reports, however, the tomb of William Ferdinand is still at the original site.

Here in Franschhoek the matching wine-cellars-turned-coach-houses are reproduced with their linking colonnade. And I still can’t help but think that — so long as you could fit a Land Rover through the doors — they would make the perfect home garage.

Staats Long Morris

Everyone knows about Gouverneur Morris, scion of one of New York’s great landowning families and given the moniker ‘penman of the Constitution’. As a signer of the Declaration of Independence his half-brother Lewis Morris III was a fellow ‘founding father’. Less well-remembered is his other half-brother Staats Long Morris (1728–1800).

Their father Lewis Morris II was the second lord of Morrisania, the feudal manor that covered most of what is now the South Bronx and has given its name to the smaller eponymous neighbourhood today.

Staats and Gouveneur owe their distinctive Christian names to the family names of their respective mothers.

Lewis II married Katrintje Staats who provided him with four children. After Katrintje died in 1730, Lewis married Sarah Gouverneur, daughter of the Amsterdam-born Isaac Gouverneur. Sarah’s uncle Abraham was Speaker of the General Assembly of the Province of New York, a role Lewis Morris II eventually filled.

Staats was born at Morrisania on 27 August 1728 and studied at Yale College in neighbouring Connecticut as well as serving as a lieutenant in New York’s provincial militia. He switched to the regular forces in 1755 when he obtained a commission as captain in the 50th Regiment of Foot, moving to the 36th in 1756.

Around that time Catherine, Duchess of Gordon, the somewhat eccentric widow of the third duke, was on the lookout for a second husband and Staats — though American, mere gentry, and ten years her junior — met with her approval. They were married in 1756 and Staats moved in to Gordon Castle to live as the Dowager Duchess’s husband.

‘He conducted himself in this new exaltation with so much moderation, affability, and friendship,’ a newspaper reported in 1781, ‘that the family soon forgot the degradation the Duchess had been guilty of by such a connexion, and received her spouse into their perfect favour and esteem.’

With the Duchess’s patronage, Lieutenant-Colonel Staats raised the 89th Regiment of Foot — “Morris’s Highlanders” — from the Scottish counties of Aberdeenshire and Banffshire though she was extremely cross when her new husband’s regiment was despatched to India where it took part in the siege of Pondichery.

In the event, Morris delayed following his regiment to India, leaving England in April 1762 and remaining there only until December 1763. When the young fourth Duke of Gordon came of age the following year, Staats turned his eyes to America and engaged in land speculation there. In 1768 he and the Duchess even went to visit their purchases in the new world, returning to Scotland in the summer of the following year.

With the fourth Duke’s help, and on the eve of the revolutionary stirrings in North America, Staats was elected to the British parliament for the Scottish seat of Elgin Burghs in 1774. He managed to hold on to it for the next ten years. Was this New Yorker the first Yale man to be elected to Parliament? I can’t find any before him, but more thorough research might prove fruitful.

In 1786 he inherited the manor of Morrisania but with the intervening separation between Great Britain and most of her Atlantic colonies General Morris thought it best to sell it on to his brother Gouverneur.

Though he had rejected a future in the world into which he had been born, Staats did return to North America in a professional capacity in 1797 when he was appointed governor of the military garrison at Quebec in what by then was Lower Canada.

Morris died there in January 1800, but his earthly remains were sent back to Britain where he was interred in Westminster Abbey — the only American to receive that honour.

Benedict of Palermo

The island of Sicily is a cross-section of the numerous kingdoms and empires which have ruled and inhabited it from the Phoenecians down to the present day. During the Norman conquest of the island — those Normans did get around — many Lombards came to help secure the Normans’ rule over the existing Sicilians who were mostly Greek and Arab. The Gallo-Italic dialect of those Lombards is still spoken in a few towns and villages speckled across the island and the settlements they founded are known as the Oppida Lombardorum.

In one such Lombard town, San Fratello, in the 1520s a son was born to an enslaved couple named Cristoforo and Diana whose piety was so highly regarded that their master granted this first-born son, Benedetto (Benedict), his freedom from birth.

From his earliest days Benedict was prone to solitude to the extent that he was mocked by his peers, in addition to being insulted frequently for his black skin. As a teenager he left the family home and became a shepherd but gave whatever he could to help the poor and those even less fortunate than him.

Discerning the call to solitude, Benedict entered the hermitage of Santa Domenica in Caronia but his reputation for holiness was such that the pious people of the island began to visit him and implore him for his prayers and miracles.

Accompanied by another member of the community, Benedict fled to other places around the island, offering great and severe penances in reparation for the sins of humanity, but no matter where he went within days the faithful had found out and pestered him.

When the founder of the hermetic community at Santa Domenica died, the brothers elected Benedict his successor, despite his lack of education and illiteracy. Benedict returned to lead the community until it was abolished in 1562 by the reforms of Pope Pius IV who urged independent groups of Francis-inspired hermits to regularise themselves into existing Franciscan orders.

Benedict went first to a Franciscan friary in Giuliana before settling into that of Santa Maria di Gesù in Palermo, the primary city of Sicily. Having been a superior of his old community, Benedict arrived at the Palermo community as a simple cook but even here his piety and talents were recognised. He was first put in charge of the novices and then, in 1578, his confrères elected him their custos or superior though he was only a brother rather than a priest.

He was known as a miracleworker across the island, but it was not only the poor, the sick, and the destitute who flocked to Benedict to seek his help. Theologians and men of learning came to visit this humble and uneducated friar. Even the viceroy of the island was known to take his counsel on important affairs of state.

In his later years, Benedict returned to being the cook of the friary until his death in April 1589. By that time the whole island of Sicily — Greeks, Arabs, Latins, all — revered this poor, humble, and unlettered friar.

Sicily’s ruler, King Philip III of Spain, ordered a magnificent tomb to be built to house Benedict’s remains in the friary of Santa Maria di Gesù, and in death his cult spread far beyond the island.

St Benedict of Palermo — or Benedict the Moor — was beatified by Benedict XIV in 1743 and canonised by Pius VII in 1807. Over the centuries, many non-white Christians came to implore his intercession and he became particularly popular among natives and mixed-race peoples in South America, in Africa itself, and amongst African-Americans in the United States.

This statue is believed to be the work of the Sevillian sculptor José Montes de Oca and was carved in the 1730s. Long in a private collection in Milan, since 2010 it has formed part of the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The Galloway Cross

What could be better than a hoard — and a Kircudbrightshire hoard at that? Sometime during the tenth century, a gentleman decided to deposit an interesting array of objects in Galloway only for them to be rediscovered by a metal detectorist in 2014.

Thus have come to us the Galloway Hoard, a collection of objects the most important of which is this pectoral cross made of silver and decorated with symbols of the four evangelists: the eagle of John, the ox of Luke, the angel of Matthew, and the lion of Mark.

As the hoard was buried when Kircudbrightshire was part of Northumbria — before the area became Scottish — the art has been identified as Anglo-Saxon from the age of the Vikings. My theory is an expert thief was at work, nicking precious objects from hapless victims — an armband gives the name of one poor Egbert in runes.

“The pectoral cross, with its subtle decoration of evangelist symbols and foliage, glittering gold and black inlays, and its delicately coiled chain, is an outstanding example of the Anglo-Saxon goldsmith’s art,” Dr Leslie Webster, an expert, said. “It was made in Northumbria in the later ninth century for a high-ranking cleric, as the distinctive form of the cross suggests.”

The Galloway Cross, before cleaning and conservation

All treasure found in Scotland must be reported to the Queen’s and Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer who in 2017 determined the hoard’s value at £1.8 million. Scots law allows the discoverer to keep the full value of the hoard if there is no owner, though as it was found on glebelands belonging to the Church of Scotland that body’s General Trustees demanded a cut as well.

The objects themselves have found a home in the National Museum of Scotland who will be exhibiting them from February until May when they will go on tour to Aberdeen and Dundee.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

- The Lithe Efficiency of the Old Constitution November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories