Arts & Culture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Other Modern in Jewish Amsterdam

Jacobus Baars’ Synagoge Oost, Linnaeus Street

There were few places where architecture’s competing forms of modernism overlapped more than the Netherlands in the 1920s. Traditionalists like Kropholler, De Stijl’s Oud, Rationalists like van der Vlugt and Duiker, and the versatile Dudok built alongside the work of the capital’s eponymous ‘Amsterdam school’ style.

The influence of the great Dutch architect Pierre Cuypers — Holland’s Pugin — might be inferred as the progenitors of the Amsterdam school (De Klerk, van der Mey, and Kramer) all studied or worked in the firm of Cuypers’ nephew Eduard.

The Dutch capital’s take on the brick expressionism originated among its Hanseatic neighbours but was sufficiently distinct to merit its own name. Architect Jacobus Baars (1886-1956) deployed the style to great effect in the work he did for Amsterdam’s then-flourishing Jewish community.

Baars designed the 1928 Synagoge Oost (East Synagogue) on Linnaeusstraat (Linnaeus Street) in the Transvaalbuurt neighbourhood that was developed in the first decades of the twentieth century.

Dutch sympathies in the then-still-recent Anglo-Boer War are obvious from the naming of local streets and squares (and, indeed, the district) after Afrikaner places, battles, and statesmen.

The architect placed the building at an angle so that the entrance could face on to Linnaeusstraat while the holy ark containing the Torah scrolls faced Jerusalem, skilfully filling in the rest of the site with clergy and school structures ancillary to the sanctuary and congregation. (more…)

Christmas Book List 2022

A reading list for the festive season

Instead, I will give an actual Christmas book list — namely, a list of books I intend to read this Christmas, snuggled up in whatsoever sufficient level of coziness I manage to achieve.

If you want to read a partial selection of books I’ve already finished reading, there is a Twitter thread you can consult (though, naturally, it doesn’t list everything).

But here are the eight books I’m looking forward to devouring.

Thomas Pink is now Emeritus Professor of Philosophy at King’s College London but he is no less busy since he has several volumes either to write or to edit on his to-do list. As a natural polymath with many interests, Tom is one of the best book-recommenders I have the privilege of knowing.

Last time we had a drink he put forward Mary Hollingsworth’s Conclave 1559: Ippolito d’Este and the Papal Election of 1559. It’s the only one on my Christmas reading list I’ve already jumped right into, and it’s excellent so far.

Last time we had a drink he put forward Mary Hollingsworth’s Conclave 1559: Ippolito d’Este and the Papal Election of 1559. It’s the only one on my Christmas reading list I’ve already jumped right into, and it’s excellent so far.

This is a period of European (and world) history I’ve not devoted any great study to, so Hollingsworth’s accounts almost attains the level of a political thriller. She’s skilled at combining archival research with an eye for the enlightening detail, which makes Conclave 1559 an enjoyable read.

Another history on my list is Last Train to Paradise: Henry Flagler and the Spectacular Rise and Fall of the Railroad That Crossed an Ocean by Les Standiford. As a child visiting the colonial city of St Augustine in Florida I remember seeing some of the extraordinary Spanish revival buildings Henry Flagler erected as part of his rail-and-hotel conglomerate.

Another history on my list is Last Train to Paradise: Henry Flagler and the Spectacular Rise and Fall of the Railroad That Crossed an Ocean by Les Standiford. As a child visiting the colonial city of St Augustine in Florida I remember seeing some of the extraordinary Spanish revival buildings Henry Flagler erected as part of his rail-and-hotel conglomerate.

Florida as we know it today was practically invented over a century ago when Flagler built his Florida East Coast Railway to bring northerners down to the Sunshine State. From 1905 to 1912 he managed a feat of engineering by extending the line across the Florida Keys.

Lawrence Durrell, despite never being a UK citizen thanks to quirks of Indian birth and bureaucracy, spent a few spells of his life working for the British diplomatic service. He’s most famous for his ‘Alexandria Quartet’, but it is White Eagles Over Serbia — a tale of a British agent caught between communists and royalists in post-war Yugoslavia — that has made it to my festal reading list.

Lawrence Durrell, despite never being a UK citizen thanks to quirks of Indian birth and bureaucracy, spent a few spells of his life working for the British diplomatic service. He’s most famous for his ‘Alexandria Quartet’, but it is White Eagles Over Serbia — a tale of a British agent caught between communists and royalists in post-war Yugoslavia — that has made it to my festal reading list.

Exotic tales of derring-do were the stock in trade of Sir H. Rider Haggard, but I have to admit I’ve never read anything by this popular Victorian/Edwardian writer.

Exotic tales of derring-do were the stock in trade of Sir H. Rider Haggard, but I have to admit I’ve never read anything by this popular Victorian/Edwardian writer.

Rectifying this error, King Solomon’s Mines is on my Christmas pile (though I was tempted by She as well).

I love a good detective novel, and the undoubted Queen of Mystery is Dame Agatha Christie. The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding is a collection of short stories including both Miss Marple and Hercules Poirot.

I love a good detective novel, and the undoubted Queen of Mystery is Dame Agatha Christie. The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding is a collection of short stories including both Miss Marple and Hercules Poirot.

In case I don’t get my fill of ze little grey cells I’ve grabbed a copy of Hercule Poirot’s Christmas as well.

A trip back to my Heimat of New York is provided by Ludwig Bemelmans’ Hotel Splendide. More famous for creating the Madeleine series of children’s books, Bemelmans immigrated to America before the First World War, volunteered for the U.S. Army, and worked at several hotels and restaurants. These latter experiences resulted in this comic novel about life behind the scenes in a swish Manhattan hotel.

A trip back to my Heimat of New York is provided by Ludwig Bemelmans’ Hotel Splendide. More famous for creating the Madeleine series of children’s books, Bemelmans immigrated to America before the First World War, volunteered for the U.S. Army, and worked at several hotels and restaurants. These latter experiences resulted in this comic novel about life behind the scenes in a swish Manhattan hotel.

Having been previously introduced to the character of Sir Edward Leithen, I thought it might be worth catching up with him in John Buchan’s The Gap in the Curtain.

Having been previously introduced to the character of Sir Edward Leithen, I thought it might be worth catching up with him in John Buchan’s The Gap in the Curtain.

The Scots barrister and Tory MP is introduced to a brilliant physicist and mathematician who explains his theory on the workings of time and the cryptic ability to see into the future. Buchan is a reliable storyteller with admirable instincts, though this series of stories veers into the realms of science fiction.

But Christmas is a light-hearted time, and so my Christmas reading list finishes with a visit to Blandings Castle thanks to Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse’s Leave it to Psmith.

But Christmas is a light-hearted time, and so my Christmas reading list finishes with a visit to Blandings Castle thanks to Sir Pelham Grenville Wodehouse’s Leave it to Psmith.

The ‘p’, of course, is silent — “like in ‘pshrimp’”.

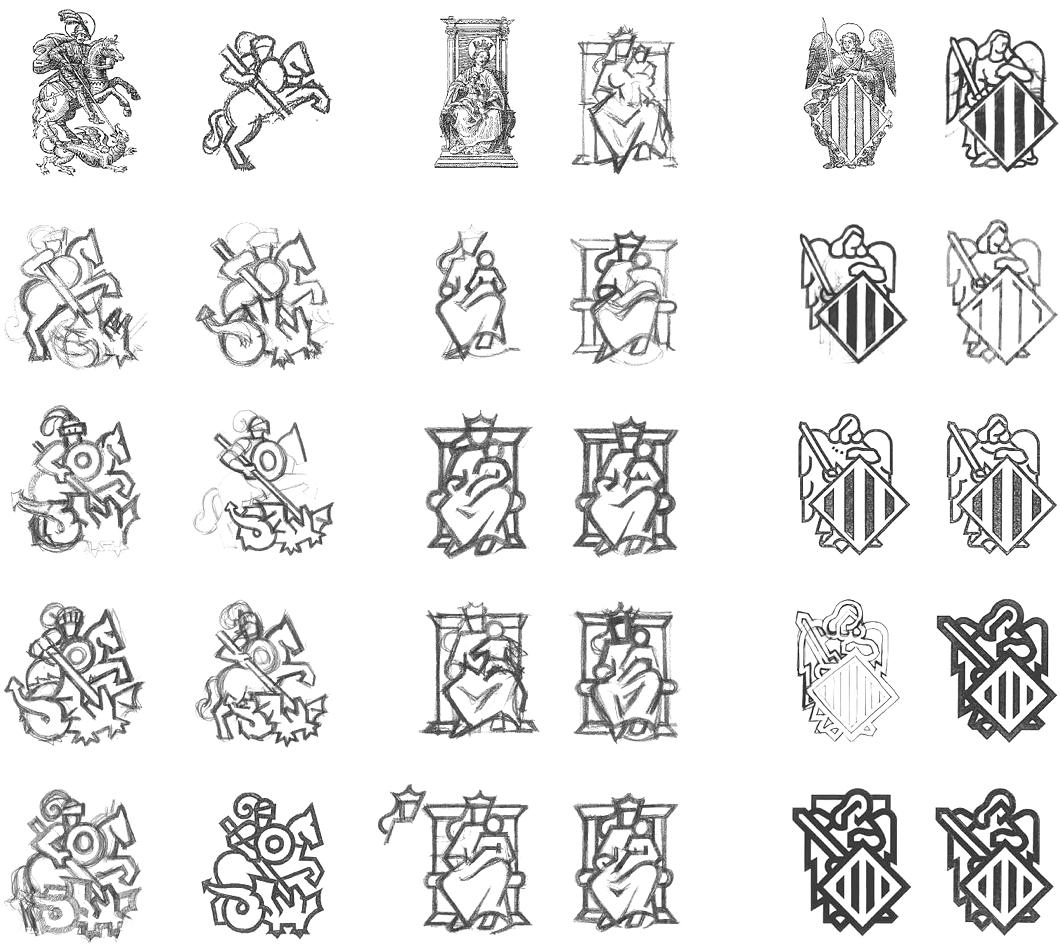

Emblem of the Valencian Courts

A friend has just brought to my attention how “incredibly, violently, sacredly based” the logo of the Corts Valencianes is.

St George slaying the dragon and the province’s Guardian Angel flanking Our Lady Seat of Wisdom is indeed an excellent sign for a legislature.

The graphic design studio of Pepe Gimeno was given the difficult job of taking a fifteenth-century engraving and somehow translating it into a modern scaleable image that could be reduced to a small size without losing clarity.

Originally they decided to focus on keeping just the Guardian Angel who bears the heraldic shield with the coat of arms of the province (technically an “autonomous community”).

When they did the work, they found the result was convincing enough to do likewise for the other figures in the engraving and include them together, preserving the historical integrity of the emblem.

The end result is an admirable modern reworking of something old. Well done.

The Headless Horseman & Hallowe’en

Washington Irving’s Legend of Sleepy Hollow — perhaps better known as the tale of the Headless Horseman — is inevitably and almost universally linked to the great feast of Hallowe’en.

There are obvious reasons for this in that Hallowe’en has become the festival of ghoulish otherworldliness, sadly now devolved into plastic mawkishness in a manner old followers of the Knickerbocker ways must surely condemn and mourn.

But this tale is always worth a revisiting; even now in early Advent.

Irving purists — we exist — might point out there there is no indication Ichabod Crane’s fateful evening ride through the Hollow took place on Hallowe’en.

Indeed, Hallowe’en is not mentioned at all in the text of the Legend, and all the author shares with us regarding the date is that it was “a fine autumnal day”:

…the sky was clear and serene, and nature wore that rich and golden livery which we always associate with the idea of abundance.

The forests had put on their sober brown and yellow, while some trees of the tenderer kind had been nipped by the frosts into brilliant dyes of orange, purple, and scarlet.

Streaming files of wild ducks began to make their appearance high in the air; the bark of the squirrel might be heard from the groves of beech and hickory-nuts, and the pensive whistle of the quail at intervals from the neighboring stubble field.

It makes for a luscious harkening of old Westchester and the Hudson Valley in the early days of the republic.

Tastier still is the scene set as the Yankee newcomer Crane enters the home of an old Dutch household for the evening’s revelries:

Fain would I pause to dwell upon the world of charms that burst upon the enraptured gaze of my hero, as he entered the state parlor of Van Tassel’s mansion.

Not those of the bevy of buxom lasses, with their luxurious display of red and white; but the ample charms of a genuine Dutch country tea-table, in the sumptuous time of autumn.

Such heaped up platters of cakes of various and almost indescribable kinds, known only to experienced Dutch housewives!

There was the doughty doughnut, the tender oly koek, and the crisp and crumbling cruller; sweet cakes and short cakes, ginger cakes and honey cakes, and the whole family of cakes.

And then there were apple pies, and peach pies, and pumpkin pies; besides slices of ham and smoked beef; and moreover delectable dishes of preserved plums, and peaches, and pears, and quinces; not to mention broiled shad and roasted chickens; together with bowls of milk and cream, all mingled higgledy-piggledy, pretty much as I have enumerated them, with the motherly teapot sending up its clouds of vapor from the midst—Heaven bless the mark!

I want breath and time to discuss this banquet as it deserves, and am too eager to get on with my story.

Happily, Ichabod Crane was not in so great a hurry as his historian, but did ample justice to every dainty.

So celebrate Hallowe’en not with plastic costumes and cheap trinketry but with Dutch delicacies and tasty treats. (And for helpful suggestions, see Peter G. Rose’s Food, Drink, and Celebrations of the Hudson Valley Dutch.)

Put aside the vampire capes and risqué nurses’ kit and, amidst candles and pumpkins of all shapes and sizes, think of the Dutch Hudson of long ago that lingers still in heart and mind.

Fire the Architects!

Good news everyone! We can fire the architects! That much-hated subset of humanity who have inflicted banality and cheap unpleasantness on the rest of us for nearly a century can finally be chucked into the dustbin of history.

As Nikos Salingaros reports in The Critic, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is revealing what experts deny, exposing the stubborn ignorance of the architectural profession.

Basically, humans don’t like bad architecture because it often communicates psychological threat, like the looming cantilevers that human brains subconsciously have difficulty making sense out of. The body then converts the psychological threat into stress as a defence mechanism, which only works if we in turn avoid bad architecture.

As Christopher Alexander and others have noticed, the key to good architecture is not a specific style but the patterns to which humans respond positively. While trained/brainwashed architects continue to feed us mush and gruel, Artificial Intelligence might be able to step in and provide us the good architecture we not only want, but need as human beings.

Inspired by this theory, I decided to use OpenAI research lab’s DALL-E platform which uses verbal descriptions and transforms them into digital images. E.g. if you put in ‘teddy bear waving a French flag’ it transforms it into an image of a teddy bear waving a French flag.

That might not seem so remarkable when you’re dealing with teddy bears, but when you feed architectural prompts into DALL-E, it delivers the goods.

My favourite architectural style is the Cape Dutch, and my favourite town is Oxford, so I decided to feed this combination into DALL-E by prompting it to give me Oxford colleges designed in a Cape Dutch style.

The results are pretty impressive — OK, to me at least — and below are about two dozen examples.

Not a single one of these buildings exists, but AI takes the parameters of what it ‘knows’ an Oxford college looks like and what it ‘knows’ the Cape Dutch architectural style is, and combines them pretty effectively.

Look at these examples and ask yourself this: would you rather live/work/study in these AI-‘designed’ buildings or in the architect-designed ‘Maison du Savoir’ in Luxembourg?

The reason why architecture is the most influential — and most oppressive — of the arts is that we effectively cannot escape it. Modern man has precious little choice over the architecture of his workplace or place of study, and increasingly less and less control over where he lives.

Too often we are condemned to spend most of our existence in bad architecture, which the body continues to convert into prolonged, low-key stress. The effects on human health, psychology, and general well-being are predictable.

Bad architecture is ultimately the fault of the innumerable powers — house builders, property developers, city councils, and other institutions — who tolerate it. Even if we don’t fire the architects just yet, we can taunt them endlessly and mercilessly by pointing out a machine can design more enjoyable and more humane buildings than they can.

Ödön von Horváth

When the shop purveying diacritical marks opened one morning in Vienna, in my mind the writer Ödön von Horváth turned up and said “Thanks. I’ll have the lot.”

It wasn’t even his real name, of course — which was Edmund Josef von Horváth. A child of the twentieth century, von Horváth was born in Fiume/Rijeka in 1901. His father was a Hungarian from Slavonia (in today’s Croatia) who entered the imperial diplomatic service of Austria-Hungary and was ennobled, earning his “von”.

“If you ask me what is my native land,” von Horváth said, “I answer: I was born in Fiume, grew up in Belgrade, Budapest, Preßburg, Vienna, and Munich, and I have a Hungarian passport.”

“But homeland? I know it not. I’m a typical Austro-Hungarian mixture: at once Magyar, Croatian, German, and Czech; my name is Hungarian, my mother tongue is German.”

From 1908 his primary education was in Budapest in the Hungarian language, until 1913 when he switched to instruction in German at schools in Preßburg (Bratislava) and Vienna.

Von Horváth went off to Munich for university studies — where he began writing in earnest — but quit midway through and moved to Berlin.

He once told his friends the story of when he was climbing in the Alps and stumbled upon the remains of a man long dead but with his knapsack intact.

Intrigued, he opened the knapsack and found an unsent postcard upon which the deceased had written “Having a wonderful time”.

“What did you do with it?” his friends naturally inquired. “I posted it!” was von Horváth’s reply.

In 1931 he was awarded the Kleist Prize for literature, but two years later the National Socialists took the helm and von Horváth thought it best to move across the border to his old imperial capital of Vienna.

Despite his anti-nationalism, he did initially join the guild for German writers set up by the Nazis, possibly to keep his works in print in the Reich while he was living in still-independent Austria.

It was in Vienna he published his best-known work: Jugend ohne Gott — “Youth without God” (first translated into English as The Age of the Fish), which marked his public point-of-no-return break with the Hitlerites.

The novel depicts a jaded schoolteacher increasingly disconnected from his profession and the world around him as the ideology of National Socialism begins to take root in the education system. (Bizarrely, it was also scantly used as the basis for a 2017 dystopian thriller.)

When Hitler’s troops marched into Austria the following year, von Horváth fled to Paris.

“I am not so afraid of the Nazis,” he told a friend there one day. “There are worse things one can be afraid of, namely things you are afraid of without knowing why. For instance, I am afraid of streets. Roads can be hostile to you, can destroy you. Streets frighten me.”

Days later, in the middle of a thunderstorm, von Horváth was walking down the Champs-Élysées — the most famous street in Paris — when a flash of lightning struck a tree, felled a branch, and struck the writer dead. He had been on his way to the cinema to see Walt Disney’s ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’.

Years ago someone recommended The Eternal Philistine: An Edifying Novel in Three Parts to me, but I have to admit I haven’t yet read it, or much else of von Horváth’s work. (He’s on my fiction wish-list though.)

His plays have been revived, too — here in London at the Almeida and the Southwark Playhouse in the past decade or so — and both The Eternal Philistine and Youth Without God are available in English from the estimable Neversink Library imprint of Melville House.

Decline at The Villager

Though constantly mourning the never-ending decline in the quality of newspaper design, I hope everyone can agree that a vast depreciation has taken place at The Villager of Greenwich Village, New York.

Whereas the Village Voice was always the pretentiously showy alternative beat-turned-hippie-turned-bobo upstart of Village publications, The Villager has played the role of the actual neighbourhood sheet that gave you the local news.

Absurdly, the otherwise magisterial and much-loved Encyclopedia of New York City doesn’t even have an entry for The Villager — not even in its second edition! — despite the paper being founded back in 1933. (The Voice was 1955.)

Behold — witness the decline:

An issue from this past week in October 1959. The nameplate features distinct lettering, flanked by the supporters of a town crier (or perhaps we should say village crier) on one side and an image of the Washington Arch on the other.

No fewer than nine stories on the front page. (It’s a standard Cusackian rule of newspaper design that the more stories on the front page the better off you are.)

There is also a helpful reminder of the upcoming election so Village denizens can do their civic duty. (more…)

Puritan in Spanish Garb

Plymouth Congregational Church, Coconut Grove, Miami

The traveller passing down Devon Road in the Grove neighbourhood of Miami might be forgiven for thinking he had stumbled across one of the ancient mission churches that Spanish antecedents had established across the American realms of His Most Catholic Majesty the King of Spain.

The traveller would be mistaken, for what he has discovered is in fact the Plymouth Congregational Church.

It was completed in 1917 by one man Felix Rebom — to a design by architect Clinton MacKenzie. According to local lore, Rebom finished the building himself using just a T-square, a plumbline, a trowel, and a hatchet.

The congregation was founded in 1897 and four years later appointed as its pastor the Rev. Solomon G. Merrick — father of the developer George Merrick who built Coral Gables.

In one of the seemingly endless series of Florida property booms, the elder Merrick’s successor encouraged the congregation to buy a large parcel of land in Coconut Grove.

Dividing it into residential plots allowed them to raise the money to build the new church on the remaining part of the land.

The massive door — hand-carved walnut backed in oak — is in fact four centuries old and comes from a disused Pyrenean monastery.

Architecturally one of the few hints that this is delightful theatre rather than historic reality is that the style, while Spanish, is more Mexican than Floridian.

Florida’s lush climate also means half the building has been taken over by surrounding greenery. I love it.

Lafayette at the Seventh

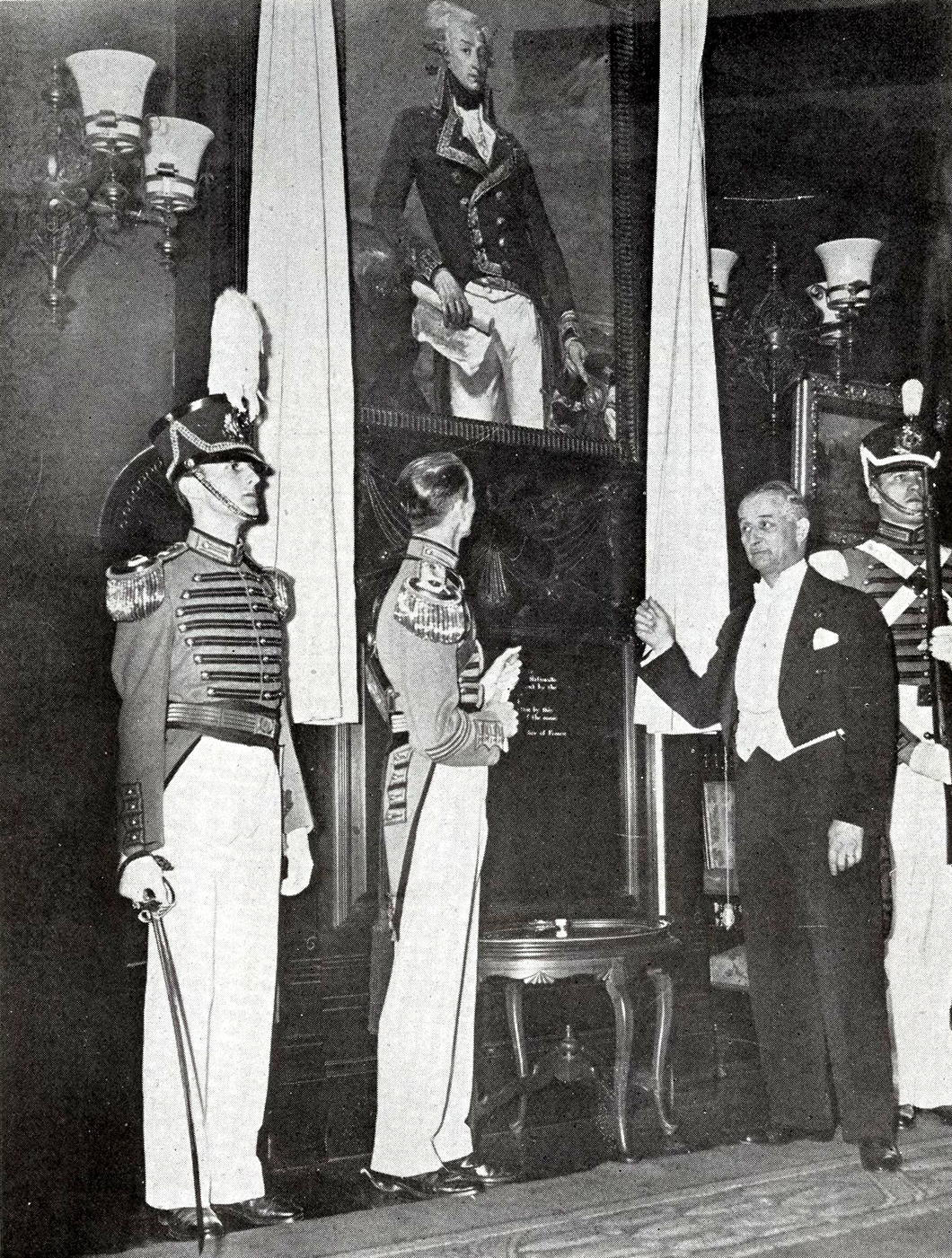

For the first century or so in the history of the United States, there was no more popular Frenchman in America than the Marquis de Lafayette. This nobleman of the Auvergne was an officer in the King’s Musketeers aged 14 and was purchased a captaincy in the Dragoons as a wedding present aged 18 in 1775. Within a year the rebel faction in North America had sent Silas Deane of Groton to Paris as an agent to negotiate support from the French sovereign, but Paris acted cautiously at first.

Lafayette — a young aristocratic freemason and liberal with a head full of Enlightenment ideas — escaped to America in secret and was commissioned a major-general on George Washington’s staff in the last of his teenage years.

Given his relative youth, Lafayette inevitably turned out to be the final survivor of the generals of the Continental Army, and his 1824 trip to the United States solidified his popularity. He visited each of the twenty-four states in the Union at the time, including New York where the predecessor of the Seventh Regiment named itself the National Guards in honour of the Garde nationale Lafayette commanded in France.

This was the first instance of an American militia unit taking the name National Guard, which in 1903 was extended to all of state militia units which could be called upon for federal service.

In honour of this connection and on the centenary of Lafayette’s 1834 death, the French Republic presented the Seventh Regiment with a copy of Joseph-Désiré Court’s portrait of the general that hangs in the 1792 Room of the Palace of Versailles. The Seventh set this in the wall of the Colonel’s Reception Room in their Armory, facing a copy of Peale’s portrait of General Washington.

The privilege of unveiling the portrait went to André Lefebvre de Laboulaye, the French Ambassador to the United States, who was given the honour of a full dress review of the Seventh Regiment on Friday 12 April 1935 before a crowd of three thousand in the Amory’s expansive massive drill hall.

Also present at the occasion was his son François, who eventually in 1977 stepped into his late father’s former role as French Ambassador to the United States. His Beirut-born grandson Stanislas served as French Ambassador to Russia 2006-2008 before being appointed to the Holy See until 2012. In April 2019, Stanislas de Laboulaye was put in charge of raising funds for the rebuilding of Notre-Dame following the fire that devastated the cathedral.

Harlem Reformed Dutch Church

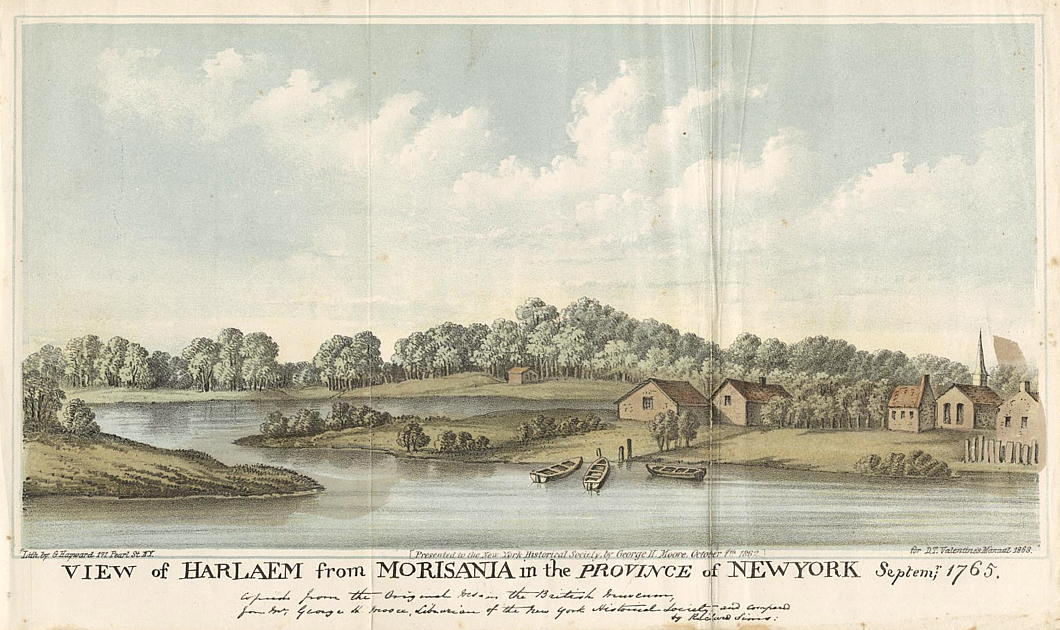

For much of Manhattan’s early colonial history, the island was home to two primary settlements: the port of New Amsterdam (later, from 1664, New York) way down at the southern tip and the town of Harlem up where the East River meets the Harlem River.

Christened after the Dutch city, Harlem is one of Manhattan’s most visible links to the Netherlands. The local newspaper is even called the New York Amsterdam News, once a prominent voice in Black America given this neighbourhood became predominantly African-American in the early twentieth century, and Amsterdam Avenue runs up as the spine of West Harlem.

Harlem was founded in 1658, thirty-four years after New Amsterdam was founded and thirty-two since Peter Minuit bought the whole island of Mannahatta off the Indians for sixty guilders.

The town’s first church was founded in 1660 but didn’t have its own dedicated building for a few years. The Harlem Reformed Dutch Church, or Collegiate Church of Harlem, was built in 1665-67 right on the banks of the Harlem River, around the site of East 127th Street and First Avenue today.

Both the building and site was abandoned twenty years later when the congregation moved to its second building, completed 1687, just a little bit further south — near where East 125th meets First Avenue, or where the entrance ramp to the Triborough Bridge meets 125th.

It is this second building, which is depicted in the view above of Harlem village from Morissania across the river in the Bronx in 1765 (below).

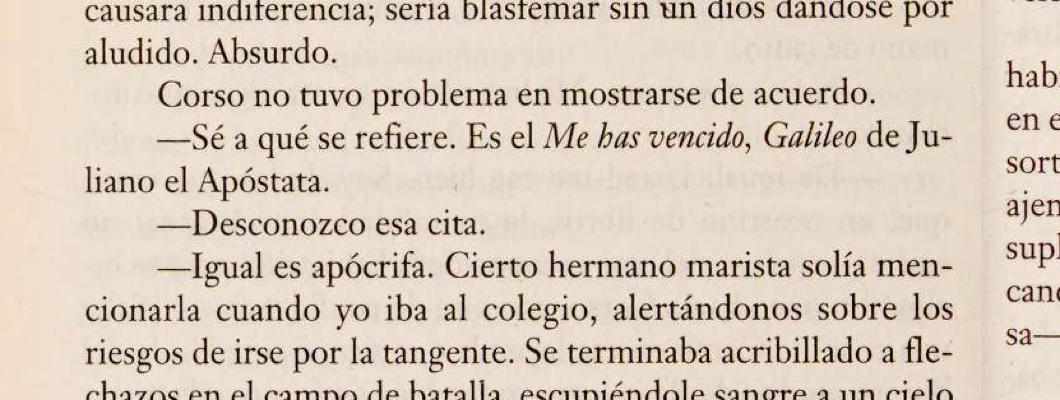

Mistranslating Apostates

ONE OF THE historical anecdotes I enjoyed being taught at school was the death of the Emperor Julian the Apostate — as relayed by our much-esteemed teacher Dr Nathaniel Kernell. This was in the Christian era with the capital at Constantinople rather than the Eternal City itself — Julian had (as betokened by his moniker) abandoned Christianity aged 20 and sought to frustrate its spread.

He wanted to promote the old Greek gods, dabbled in vegetarianism, and even tried to rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem. Mysterious fires consumed the workers tasked with that final project and it is presumed many Jews didn’t want to be dragged into the Emperor’s political project the animus of which was opposition to Christianity rather than promotion of Judaism.

Anyhow, none of Julian’s projects came to much fruition and as he lay dying from an injury in battle, the apostate emperor realised the futility of his life’s work with his final words: νενίκηκάς με, Γαλιλαῖε, or ‘Thou hast defeated me, Galilean!’

At the moment I am reading a book by Arturo Pérez-Reverte and stumbled across a mistranslation from the Spanish that would have been avoided if only the translator had enjoyed the privilege of being taught by Dr Kernell.

It turns out that the Spanish word for ‘Galilean’ is ‘Galileo’. Pérez-Reverte’s translator, alas, failed to understand one of the characters reference to Julian’s final words and mistook Christ our Saviour for an Italian astronomer, mistranslating the phrase as “You have defeated me, Galileo”.

Worth a wry smile, given the solid 1,200-year gap between the death of Julian the Apostate and the birth of Galileo Galilei.

The Dumas Club is a delightfully weird and intriguing tale, though, and I look forward to reading more by Pérez-Reverte — no matter who the translator is.

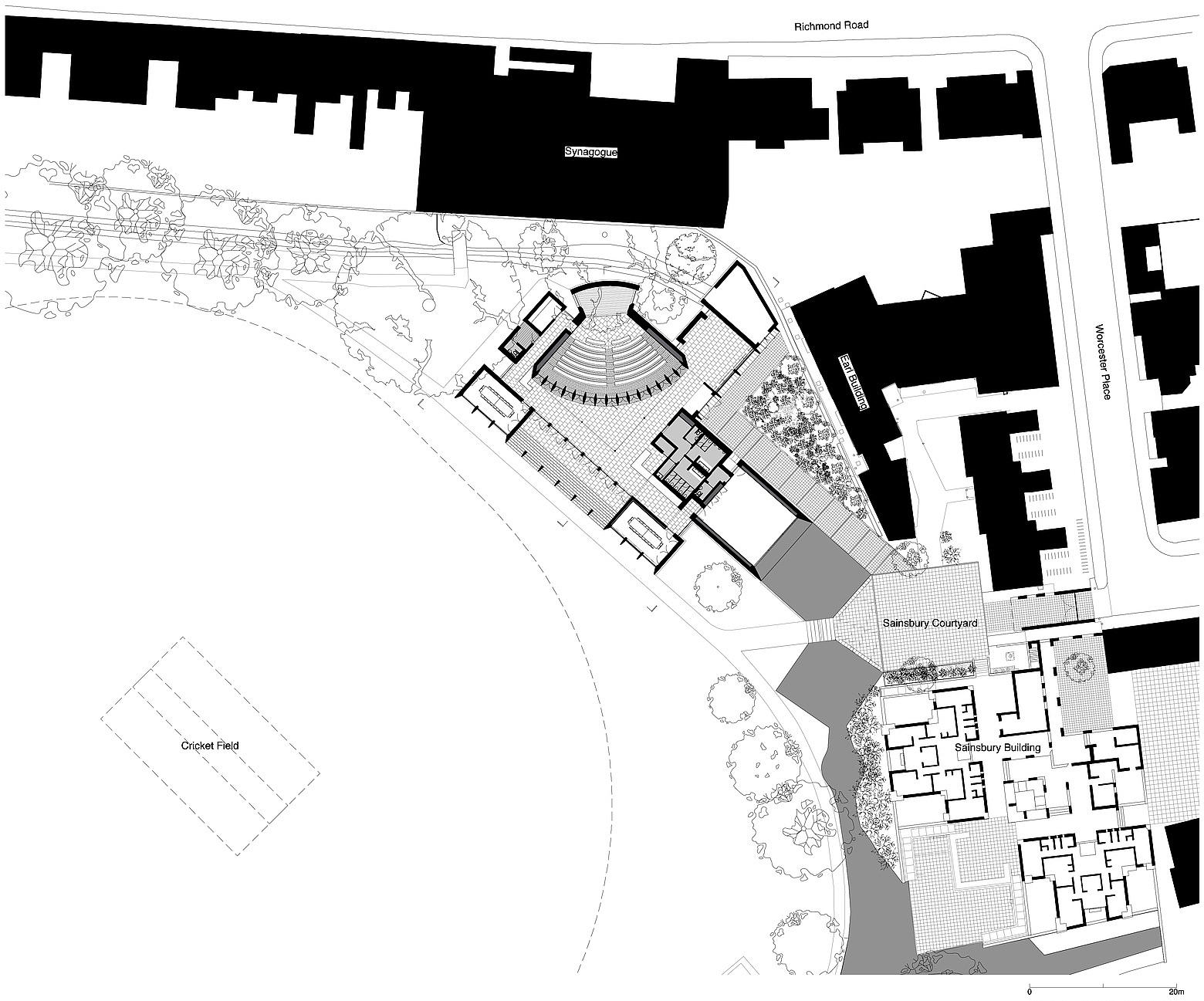

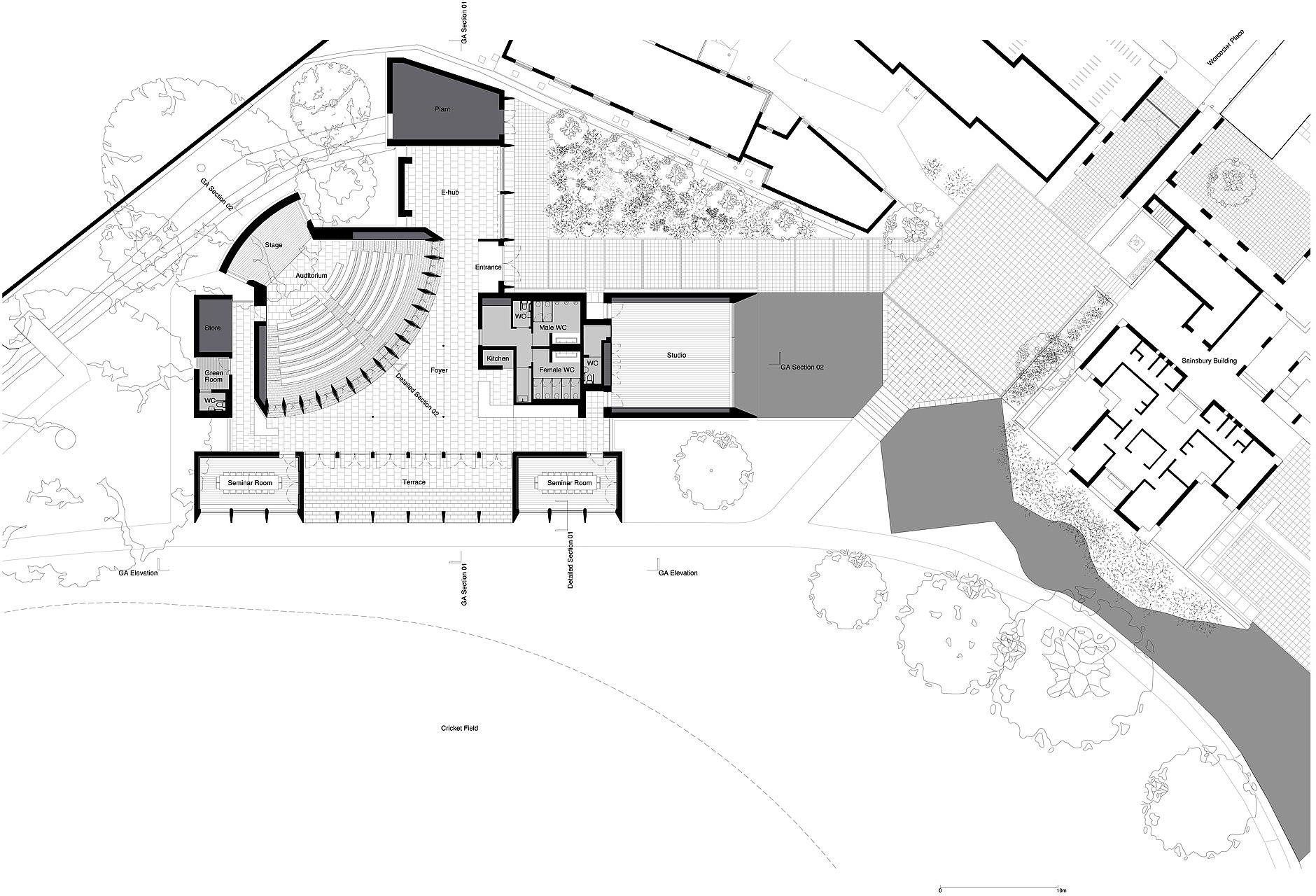

The Sultan Nazrin Shah Centre

Níall McLaughlin Architects at Worcester College, Oxford

WORCESTER is one of the most spacious and scenic of Oxford’s colleges. The classical symmetry of its entrance terminates the view down the gentle curve of Beaumont Street from the Ashmolean Museum. The twenty-six acres of its grounds are pastoral, with lake, gardens, and the broad expanse of a cricket pitch.

Craftily inserted into this arcadia is the Sultan Nazrin Shah Centre designed by Níall McLaughlin Architects. Collegiate work is familiar to this firm, whose new library at Magdalene College, Cambridge, has won them this year’s Stirling Prize, and the Shah Centre provides new useful facilities for the college without giving it the middle finger.

It is named in gratitude to the generosity of an old boy of the college, HRH Nazrin Ali Shah of Perak, who delights in the title of Sultan, Sovereign Ruler, and Head of the Government of Perak, the Abode of Grace, and its dependencies. Judging by the outcome — itself shortlisted for a Stirling Prize in 2018 — I think he spent his money well.

Tempting though it might be to have a gentle wander through the grounds of the college first, the Shah Centre is best approached through the humble entrance lodge nestled in the corner of the L-shaped Worcester Place north of the college.

You are led to a little piazza — the Sainsbury Courtyard — framed by a pair of just-below-foot-level diamond-shaped shallow ponds of Kahn-ian geometry. (They are actually a tiny extension of the college lake.) The broad expanse of cricket pitch beyond, connected by a flat wooden bridge segmenting the two diamond ponds, is alluring. But off at a 45-degree-angle on the right, the entrance to the Shah Centre bids the visitor on.

Beyond the limestone cladding you move indoors to a sea of light-treated oak, in the thin supporting columns of the one-storey entrance hall curving around the arc of the lecture theatre and in the trelliswork ceiling.

To the left, the dance studio looks out onto the pools through three giant panes of floor-to-ceiling glass.

To the right, a small bar can double as a registration desk.

The lecture theatre seats 170 and is accessed through a curve of wooden slats that hide panels that can swing out if closing the space is necessary.

Auditoria with ceilings sloping down toward the stage usually feel cramped but here the ceiling is arranged in sharp corrugations (like the flanges of the Gonbad-e Qabus) which capture the light from the clerestory behind.

The feeling is one of spaciousness: rather than facing downwards they are like rays of the sun reaching outwards and up. Instead of wings offstage, there are tall windows of a single sheet of glass flanking, offering natural side light.

The view from the stage is even better, looking out at the gentle curve of clear windows breaking at near-half-way, dividing the anterior spaces below from the open skies above.

Straight out from the auditorium is the terrace with its steps flowing gently down to the field beyond.

It is from the cricket ground that we get the best view of the Shah Centre. The lines are elegant, and there’s a hint of the better architects from Italy’s fascist era — Pagano or Terragni, not Piacentini. The easy movement of space and light, with a gentle breeze rolling off the green.

The architectural genius of the Oxford college as a type is that it allows for the magnificent to be completed on a humane scale for an intimate community of students, scholars, and academics. Níall McLoughlin’s skill at achieving this in a modern idiom is what makes the accolades he accrues — fickle gifts at the best of times — so justified in his case.

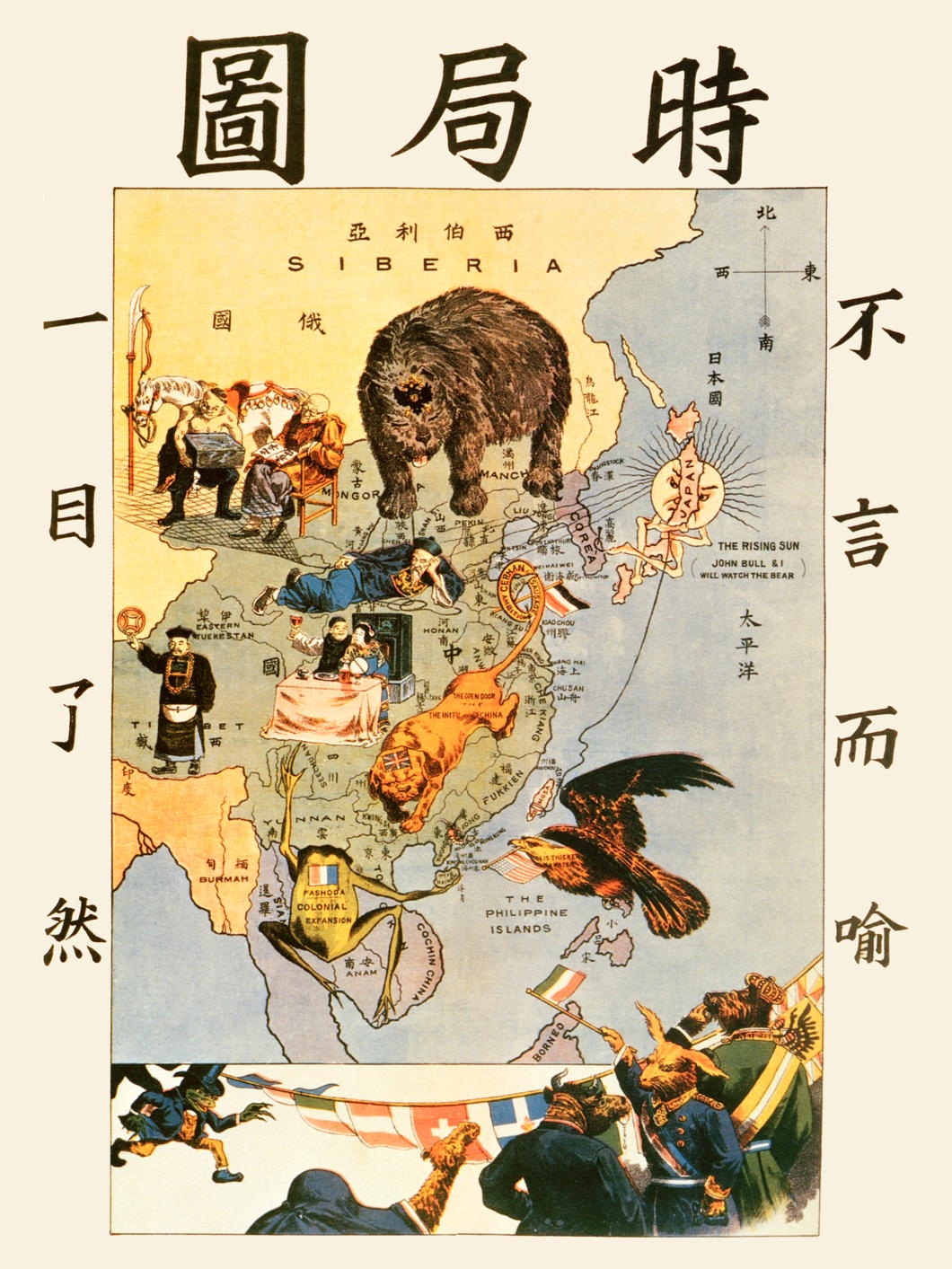

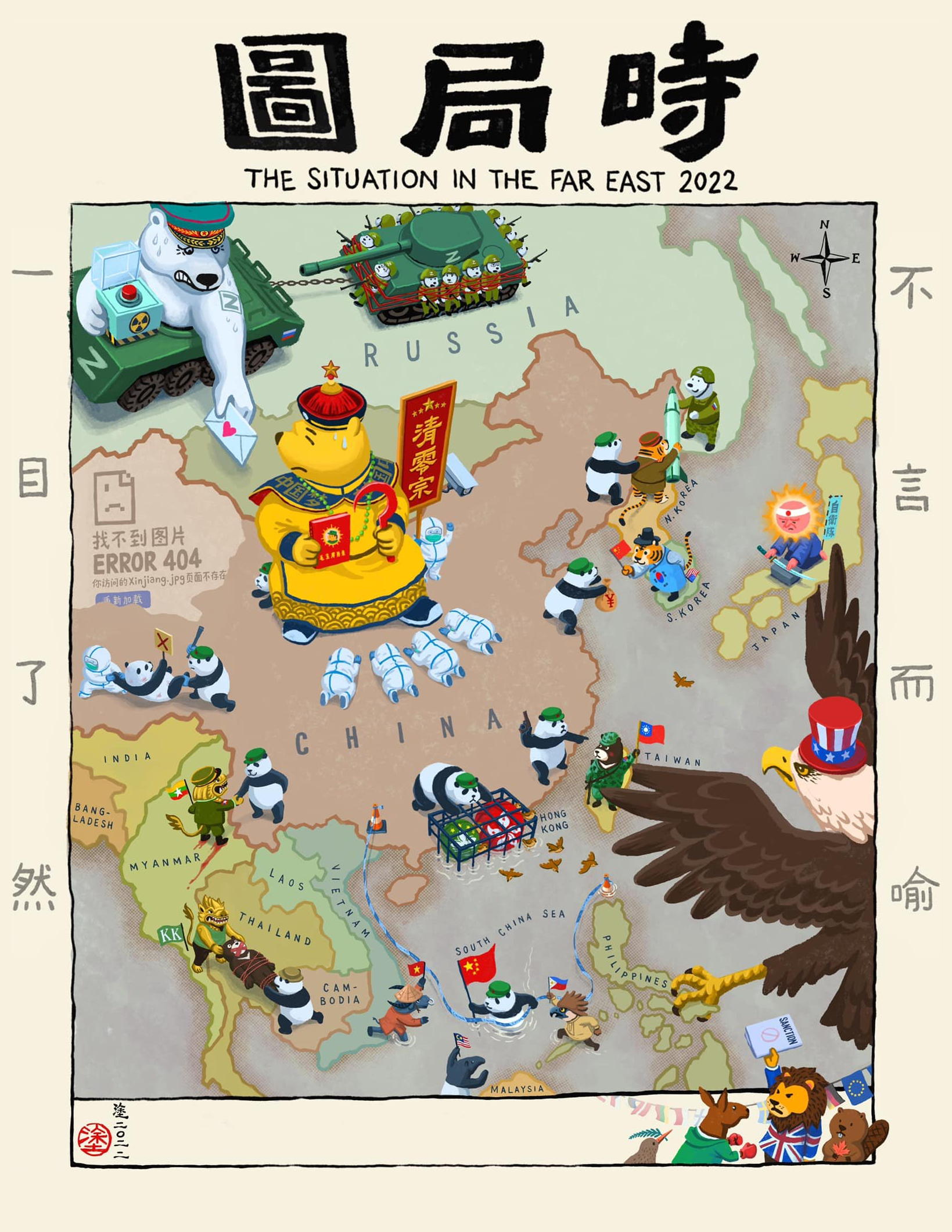

The Situation in the Far East

A century-old geopolitical cartoon is updated for today

Tse Tsan-tai — or 謝纘泰 if you fancy — was by any standard a remarkable man. Born in New South Wales, this Chinese-Australian Christian was a colonial bureaucrat, nationalist revolutionary, constitutional monarchist, pioneer of airship theory, and co-founded the South China Morning Post — still one of the most prominent newspapers in the Orient.

Tse’s most important visual contribution was a widely distributed political cartoon usually known in English as ‘The Situation in the Far East’ or in Chinese as the ‘Picture of Current Times’ (below).

Crafted as a propaganda measure to warn his fellow Chinese of the designs of foreign powers, the cartoon depicts the perils facing the Middle Kingdom.

Japan, with its expanding navy, proclaims it will watch the seas with its ally, Great Britain. The Russian bear looms from Siberia, crossing the border into China. A British lion sprawls over the land, its tail tied up by the “German Sausage Ambitions” at Tsingtao. The French frog guards Indochina while the American eagle lurks from the Philippines.

Meanwhile, the Chinese figures show sleeping bureaucrats and carousing intelligentsia unresponsive to the external threats.

Now the exiled Hong Kong artist Ah To (阿塗) has updated ‘Situation’ to reflect the realities of 2022. (more…)

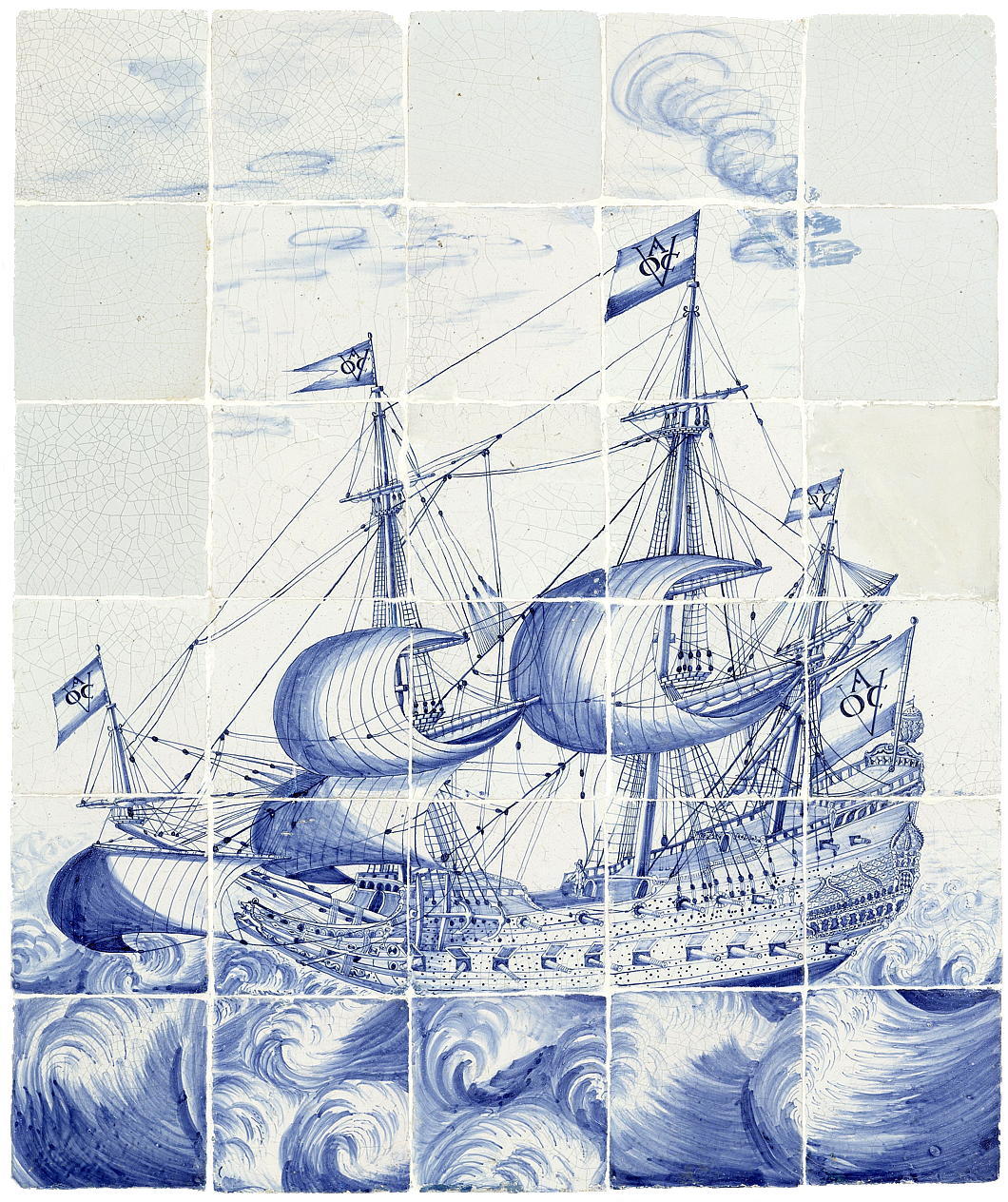

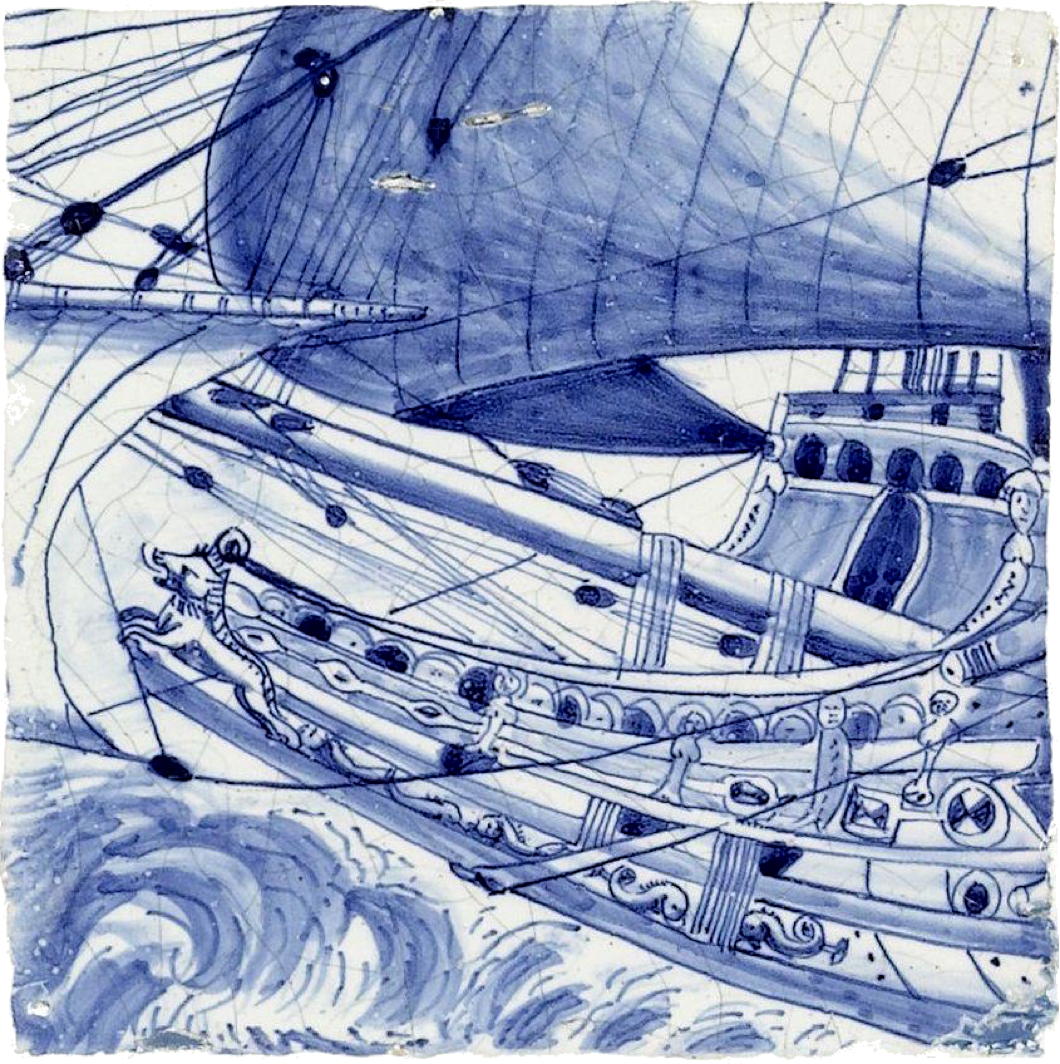

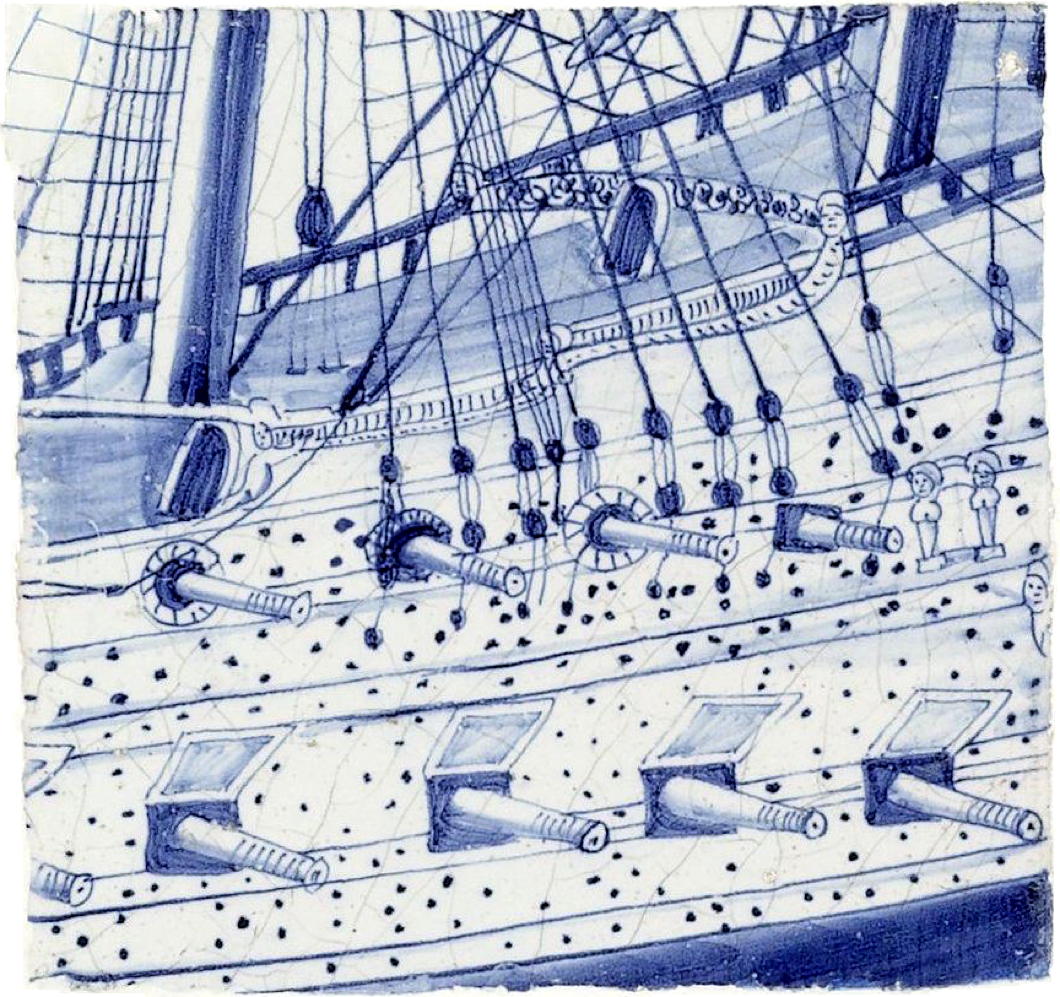

An East Indiaman

English sea-goers and merchants commonly referred to any ship of the Dutch VOC (or of other similar companies) as an ‘East Indiaman’.

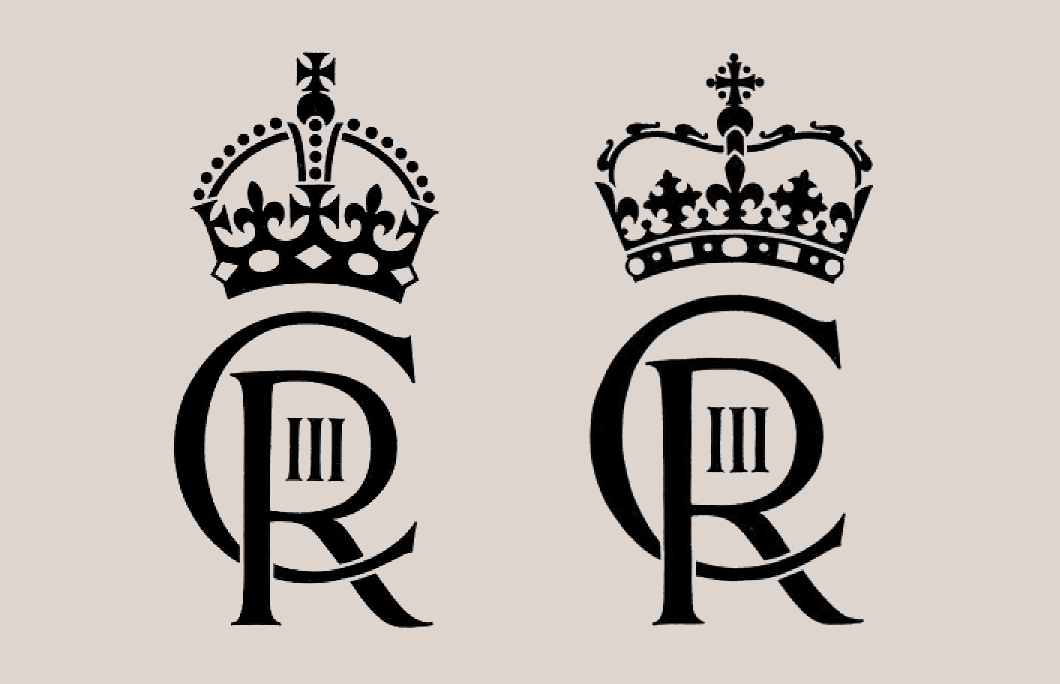

Cypher Shift

Out with the old, in with the new: the King has released his new royal cypher, with a stylised CR III replacing the familiar EIIR. As with so many things, I am sure we will get used to it with time.

Given the longevity of the late Queen’s reign it will be some time before we see it appearing on pillarboxes, but it will enter our lives more quickly via postal franking, stamps, currency, and uniforms.

Many are trying to come up with complex, almost mystical, explanations for why St Edward’s Crown has been replaced with the Tudor crown atop the cypher. More likely, I suspect, is that it is a useful means of giving the new reign a respectful visual differentiation from its preceding one.

I’ve always been rather fond of the Tudor crown, and the Caledonian version of the new cypher rightly includes the Crown of Scotland — the oldest amidst the Crown Jewels of this realm as (unlike England) Scotland was spared the iconoclastic destruction of Cromwell’s republic.

The new royal cypher, left, and its Scottish variant, right.

Bonnington Square

This little enclave is one of the best-kept secrets of London. I used to live just around the corner from Bonnington Square and walking into it was like entering a secret world.

Just steps from the gritty urban world of the Vauxhall gyratory there is a verdant realm where a good coffee can be had and where many neighbours actually know eachothers’ names.

Built to house railway workers, the whole square was compulsorily purchased by that archetype of grim 1970s misery, the Inner London Education Authority, to be demolished as a sports ground for the neighbouring school.

Within a decade, however, no demolition had been approved and the squatters had moved in — in this case organising a cooperative, building a community garden, and running a shop. They managed to negotiate the purchase of their homes from the Greater London Council and Bonnington Square was saved.

Gardeners have turned its streets into one of the most lushly verdant corners of central London, and now this five-bedroom house is up for grabs. If you have £1.9 mil going spare it would be a nice place to live.

For an ardent sun-lover like me the roof terrace — with barbecue artfully inserted into the old chimney breast — is the best feature, along with the proximity to the excellent Italo Deli.

L’Élysée à la plage

The Fort de Brégançon: Riviera Retreat of France’s Presidents

When France’s head of state needs to let his hair down every summer, the Republic has a convenient presidential residence just for him to do so: the Fort de Brégançon on the Côte d’Azur.

There has been a fortress here since at least mediæval times, and Gen. Buonaparte (later emperor) ordered its ramparts renewed after the retaking of Toulon in 1793. It continued to serve military purposes until 1919, but in 1924 it was leased out to a local mercantile family, the Tagnards.

They passed their lease on to the former government minister Robert Bellanger, who improved the island greatly, connecting it to the water and electricity supply, building the causeway linking it to the mainland, and laying out the Mediterranean garden. Bellanger’s leased expired in 1963 and Brégançon returned to the property of the state.

President de Gaulle stayed a night on the island in 1964 but found the bed too small and the mosquitos too bothersome. Nonetheless, his wartime comrade René-Georges Laurin (mayor of Saint-Raphaël up the coast) convinced him it would make a suitable summer residence that befitted the dignity of France’s head of state.

The architect Pierre-Jean Guth was seconded over from the Navy to adapt and update the fort to this end. The rooms are a little small, but their cozy intimacy adds to the fort’s informality. The presidential bedroom features a Provençal bed facing the sea with a view towards the nearby island of Porquerolles.

Pompidou and Giscard enjoyed the island but Mitterand mostly neglected the island except when welcoming Chancellor Kohl and Taoiseach Garrett Fitzgerald. Chirac and his wife took up Brégançon and were often seen by the locals on their way to Mass.

Sarkozy liked to be photographed on his jogs from the island but after he abandoned his wife and took up with his mistress he preferred holidaying at Carla Bruni’s far grander and more comfortable summer residence.

Hollande opened the fort up to public visitors, hoping to recoup some of the costs of maintaining the property. Macron has taken to the island frequently for his summers, for meetings with foreign leaders, and for working weekends with his ministers.

With summer fires raging, a minority in parliament, and myriad other problems brewing, no doubt Macron has much on his agenda.

All the same, for France’s sake, we can’t help but hope Monsieur le Président has a happy holiday. (more…)

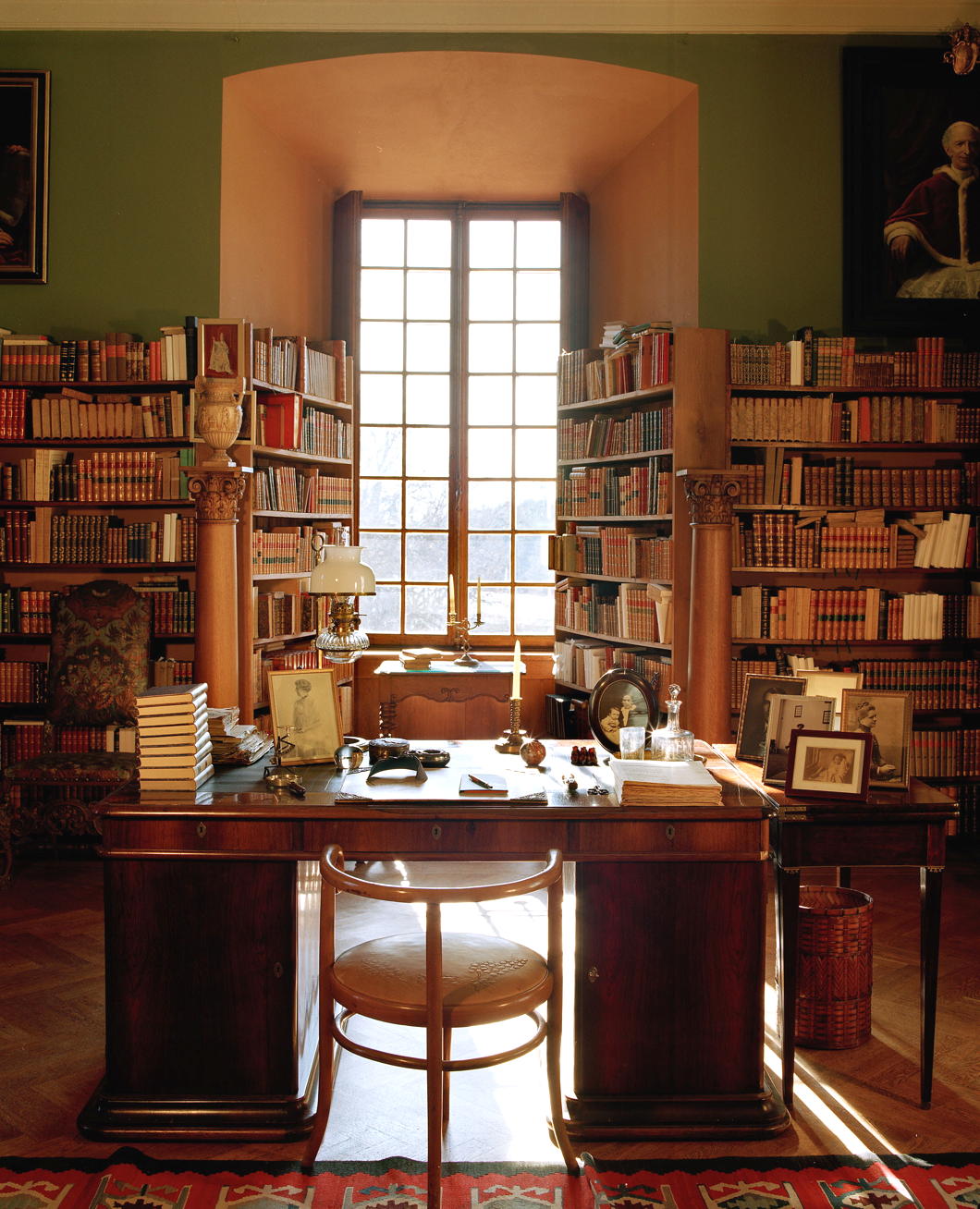

A Desk in Sweden

(In honour of his descendant coming to London for a coffee last month.)

Alys Beach

My list of favourite things starts with sunshine, good architecture, and the beach — Florida’s Alys Beach has all three. This is the third of the communities on the Gulf Coast designed by Duany Plater-Zyberk.

Their first, Seaside — well known as where ‘The Truman Show’ was filmed — is iconic but now feels a little sterile and over-planned. It has earned its place in the history books of urbanism and architecture regardless.

Rosemary Beach, their second development, was a vast improvement and based its architecture on the actual Spanish colonial styles used when the Cross of Burgundy flew over Florida rather than the more Mediterranean-influenced Spanish Colonial Revival of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Alys Beach is a splendid melange — a touch of the Cape Dutch, Bermuda here, the Maghreb there, and every now and then a hint of the French Caribbean. And it works: this is one of the most successful attempts at a beautiful and pleasing urban arrangement in twenty-first century America.

If any criticism can be issued it’s that Alys Beach is a holiday destination that will never be a “real” community where most people dwell all year round.

But if I was sitting en famille round a rooftop firepit watching the sun go down, I don’t think I’d complain.

St George’s Basilica, Prague Castle

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories