Arts & Culture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Le monde diplomatique

The German edition of Le monde diplomatique underwent a complete overhaul not too long ago. Unlike the main French edition of Le monde diplo, which exhibits the exact style of a French newspaper of mediocre design circa 1996, the German edition now exudes a certain calm and composed modernity. The redesign is the work of the German typographer and designer Erik Spiekermann, whom the Royal Society have named a Royal Designer for Industry (entitling him to an HonRDI after his name; only “hon” because he is not a British subject). Mr. Spiekermann was responsible for the much-lauded redesign of The Economist, the magazine you read when the airport lounge doesn’t have a copy of The Spectator.

Saskatoon Cathedral

Matthew Alderman’s hypothetical counter-proposal

Matthew Alderman has designed a hypothetical counter-proposal for the new Catholic cathedral in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan which is infinitely more beautiful than the ugly modernist thingamajig that the diocese is actually building. Matt elaborates upon the problematic nature of the modernist design here and here.

Argentina’s Voice: La Prensa

TIME magazine, 26 October 1942

In the ornate Paz family crypt in Buenos Aires’ comfortable La Recoleta cemetery, honors came thick last week to the late José Clemente Paz, founder of Argentina’s La Prensa. The Argentine Government issued a special commemorative postage stamp. Nationwide collections were taken to erect a monument. U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull sent a laudatory cable, as did many another foreign notable. It was the 100th anniversary of the birth of Argentina’s most famous journalist.

In the ornate Paz family crypt in Buenos Aires’ comfortable La Recoleta cemetery, honors came thick last week to the late José Clemente Paz, founder of Argentina’s La Prensa. The Argentine Government issued a special commemorative postage stamp. Nationwide collections were taken to erect a monument. U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull sent a laudatory cable, as did many another foreign notable. It was the 100th anniversary of the birth of Argentina’s most famous journalist.

Although Don José has been dead for 30 years, the newspaper he founded 73 years ago has not changed much. La Prensa is THE Argentine newspaper, is one of the world’s ten greatest papers.

Polish, Curiosity, Comics.

A cross between the London Times and James Gordon Bennett’s old New York Herald, La Prensa is unlike any other newspaper anywhere. In its fine old building the rooms are lofty and spiced with the odor of wax polish, long accumulated. Liveried flunkies pass memoranda and letters from floor to floor on an old pulley and string contraption. But high-speed hydraulic tubes whip copy one mile from the editorial room to one of the world’s most modern printing plants—more than adequate to turn out La Prensa’s 280,000 daily, 430,000 Sunday copies.

Argentines are minutely curious about the world. Although newsprint (from the U.S.) is scarce, La Prensa usually carries 32 columns of foreign news—more than any other paper in the world. Four years ago most was European—today New York or Washington has as many datelines as London.

La Prensa’s front page is solid (save for a small box for important headlines) with classified ads. So, usually, are the following six pages—one reason the paper nets a million dollars or more annually. Lately La Prensa has made some concessions to modernity: it now carries two comic strips, occasional news pictures.

Deliveries, Duels, Discussions.

La Prensa will not deliver the paper to a politician’s office; he must have it sent to his home. It will not call for advertising copy. No local staffman has ever had a byline.

South American journalism is more hazardous than the North American brand. La Prensa’s publisher and principal owner, Ezequiel Pedro Paz, Don José’s son, has twice been challenged to a duel. Because he is a crack pistol shot, neither duel was fought. Now over 70, Don Ezequiel shows up at the paper punctually at 5 p.m. for the daily editorial conference with Editor-in-Chief Dr. Rodolfo N. Luque. Present also is his nephew and heir-apparent, handsome Alberto Gainza (“Tito”) Paz, 43, father of eight and ex-Argentine open golf champion. Significantly, La Prensa’s owner-publishers visit their editor-in-chief and not vice versa.

La Prensa’s foreign affairs editorials often wield great influence, but have not budged the isolationism of President Ramón Castillo. The paper has supported Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, pumped for the United Nations, denounced the totalitarians. But it speaks softly. When Argentina’s President Castillo gagged the press with a decree forbidding editorial discussions of foreign events, admirers of Don José recalled how he once suspended publication in protest at another Argentine President’s like decree. If old Don José were now alive, declared they, he would again have stopped La Prensa’s presses rather than submit to Castillo’s regulations. — TIME, Oct. 26, 1942

TIME magazine, 16 July 1934

Prensa Presses

On the roof of the imposing La Prensa building in Buenos Aires’ wide Avenida de Mayo is a large siren. Its piercing screech, audible for miles, heralds the break of hot news. Long ago a city ordinance was passed forbidding use of the siren and the publishers rarely sound it nowadays. But when some world-shaking event takes place, La Prensa’s horn shrills and a Prensa office boy trots downtown to pay the fine before its echo has died away.

Last week the fingers of La Prensa’s acting publisher, Dr. Alberto Gainza Paz, itched to push the siren button. There was much to celebrate. Not only was it Nueve de Julio, Argentina’s Independence Day, but potent old La Prensa was formally inaugurating a new $3,000,000 printing plant, finest in South America. Its holiday edition ran to 725,000 copies— 150,000 more than its previous record.

The plant is housed in a new building a half mile from the main office, in the rent-cheap industrial district. It is linked to the editorial rooms by pneumatic tubes. The installation includes a 21-unit Hoe press similar to that of the New York World-Telegram. The press is driven by 56 motors, is fed by 63 rolls of newsprint and two six-ton tanks of ink. A normal edition of 250,000 copies (400,000 Sunday) is spewed out in considerably less than an hour. Since Buenos Aires is so far from the Canadian pulp market, La Prensa keeps on hand up to 7,500 tons of newsprint, enough to supply its needs for three months or, in emergency, to produce a smaller paper for a year.

Completion of the new plant marked the almost complete retirement of La Prensa’s publisher and principal owner, Don Ezequiel P. Paz. Son of the late Dr. José C. Paz, who turned out the first copy of La Prensa 65 years ago on a tiny hand press, Don Ezequiel started to work around the shop as a youngster in 1896, took full charge while still a young man. He devoted his life completely to his newspaper, spent nearly all his waking hours in his incredibly ornate office, denied himself to practically all callers except his editors. Past 60, of nervous temperament, he lives nearly half the year at his French estate near Biarritz. On his transatlantic trips he customarily takes a large party of relatives, and for the sake of his diet, a cow. The cow makes the round trip but must be sacrificed in sight of her native land because of Argentina’s rigid quarantine against all imported cattle. Don Ezequiel sailed for Biarritz last month, regarding the new plant as perhaps the last important milestone in his publishing career. Childless, he turned his responsibilities over to his nephew, youthful Dr. Alberto Gainza Paz, whom he carefully tutored as he himself had been trained by Founder José. So puny in boyhood that he was not expected to live. Dr. Gainza made of himself one of the foremost amateur athletes in Buenos Aires.

Beyond dispute La Prensa is the leading newspaper in South America, is read throughout the continent. Sternly independent, it truckles to no political party, even refuses to accept political advertising on the ground that if any politician is really as good as he claims, he is legitimate news and will be reported accordingly.

To U. S. newsreaders, a typical copy of La Prensa is a curious sight. Prime headlines are massed in a six-column box on the front page, which is otherwise filled with classified advertisements. The “classifieds” run through the next six pages and supply the wherewithal for Publisher Paz’s proud boast that La Prensa is independent of large commercial advertisers. The news pages begin with a lengthy, learned article which most readers skip, but which is supposed to wield strong influence in high places. The news columns proper are top-heavy with foreign news. Probably no other newspaper in the world spends so much money on cable tolls—a fact partly due to Argentina’s cosmopolitan population. La Prensa demands important political speeches in full. It “discovered” Albert Einstein for the world press by first requesting United Press to interview him on his theory of relativity 15 years ago. After La Prensa printed it, U. P. decided to try Einstein on its U. S. clients. La Prensa gives any amount of space to amateur sports, demands play-by-play coverage on important chess matches, but refused Argentina’s Prizefighter Luis Firpo more than the barest mention even at the height of his popularity. It prints voluminous market news, lottery drawings, crossword puzzles, no comics except on Sunday. Its newsphotos are rare and inferior. On Sunday it offers rotogravure in color.

Employing no advertising salesmen, La Prensa never solicited an advertisement. Until a few years ago it would not permit advertisers to use large display type. It rejected a substantial Wrigley campaign because it hesitated to introduce the gum-chewing habit to Argentina. It saw no sense in a Quaker Oats breakfast food advertising program because Argentinians do not eat breakfast. However, La Prensa does print many an advertisement of doctors specializing in venereal diseases. La Prensa is one of the wealthiest newspapers in the world. The Paz family took from it enough to live in ease, plowed back huge sums for improvements and. notably, social services. One of the oldest services is a general delivery postal service, begun after the great immigration of the 1860’s when the Argentine post office proved hopelessly inadequate. To this day a letter addressed care of La Prensa will reach any Argentinian of known residence. Also La Prensa maintains free medical and surgical clinics for the poor, free legal service, and a free three-year music school. Its building houses banquet rooms, lecture halls, library, gymnasium.

The Paz family likes to regard La Prensa as Argentina’s property, themselves as hired managers. — TIME, July 16, 1934

CUSACK’S NOTE: La Prensa was confiscated by Peron’s dictatorship and its assets given to the Peronist CGT trade union. The family’s assets were restituted in 1988 and the newspaper refounded, but its readers had by then moved elsewhere and the La Prensa continues to this day in a much reduced form; its old headquarters on the Avenida de Mayo is now the Casa de la Cultura. The conservative La Nacion is now the only broadsheet in Argentina.

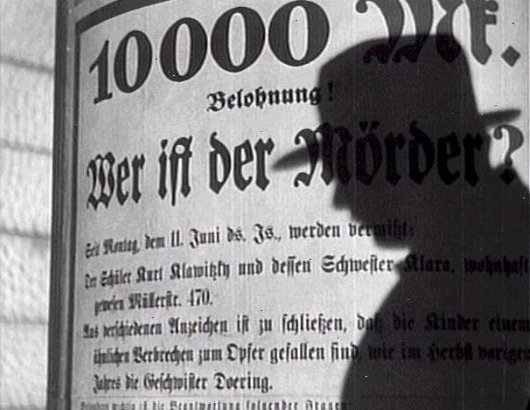

«Metropolis» rediscovered

Fritz Lang’s «Metropolis» was one of the most groundbreaking films of the silent era, and so the news that scenes previously lost have been rediscovered is most welcome. While «Metropolis» is one of those films that is perhaps best appreciated if only viewed once, I certainly look forward to a restored version being released in the next few years.

Still, my favorite of Fritz Lang’s works remains the classic «M», a sound film released in 1931, a few years into the talkie era. Peter Lorre is at his best in the starring role, and of course with Lang at the helm, «M» is expertly shot. Those whistled notes from Peer Gynt are never the same again after seeing this film!

So this is why people live in California

Jackson Street, San Francisco: 20 rooms, 9 bedrooms, 7 full bathrooms, 3 half-bathrooms, 7 fireplaces, hardwood floors, 4 storeys, an elevator, 4-car garage, and off-street parking.

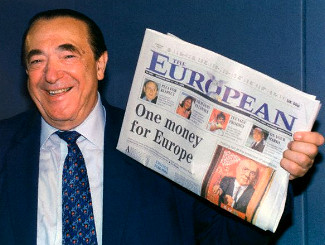

The European I grew up with

When I was a kid, The European — the weekly broadsheet that billed itself as “Europe’s national newspaper” from 1990 to 1998 — was my favourite newspaper and was an indelible part of our Sunday routine in the Cusack household. First Mass, then a trip to the pastry shop, then pick up The European at the newsagents next door, and back home to read and munch al fresco.

The paper was fiercely Euro-federalist until Andrew Neil took over, so I suspect were I to look back on a few copies now, I would probably strongly disagree with its politics. The late Peter Ustinov was a columnist, and he was not just a European integrationist but indeed a major supporter of world federalism (i.e. the abolition of nations and the rule of the planet by a single government; in theory democratic but inevitably a dictatorship of course).

Nonetheless, it was a very broad paper, with news from all across the continent from Cork to Constantinople, and I have no doubt its coverage played at least some role in the formation of your humble and obedient scribe.

The Primera Revista Latinoamericana

We are of the opinion that the more publications, the merrier, and so we certainly welcome the foundation of the Primera Revista Latinoamerican de Libros. The PRL, which is a sort of Hispanic version of the TLS, started printing last September and is based right here in New York. The bimonthly is published in Spanish but reviews both books that are printed in Spanish and books printed in English. Again, like the TLS, it is not limited to book reviews but features other literary essays as well.

The head honcho at the PRL is Fernando Gubbins, who has earned a master’s degree in Public Affairs from Columbia here in New York and a philosophy degree from the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru. Mr. Gubbins previously edited the opinion & editorial section of the Peruvian newspaper Expreso, and has worked with the Economist Intelligence Unit.

Not being a hispanophone, I am not qualified to render judgement on the quality of the publication’s content, the PRL in print is well designed and has a very traditional but modern feel to it, and it was a pleasure flicking through its pages. The Primera Revista is a welcome addition to the literary world of New York, and of Latin America.

“The Bridge of San Luis Rey”

New Spain never looked so good as in the 2004 film of Thornton Wilder’s novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey. This is no doubt partly because it wasn’t filmed in New Spain but in Old Spain (specifically in Toledo and Málaga).

New vice-regal flag for New Zealand

Elizabeth II, Queen of New Zealand, recently approved a new vice-regal flag (above) for her governor-general, His Excellency the Honourable Anand Satyanand, PCNZM, QSO, KStJ. The flag has a blue field charged with the shield from the coat of arms of Her Majesty in Right of New Zealand, topped by St. Edward’s crown. The previous flag (below) was of the standard viceregal type for the British Commonwealth of Nations, depicting the crest from the British royal arms with a scroll bearing the name of the dominion.

His Excellency, incidentally, is the first Catholic governor-general in the history of New Zealand.

Return of the Warner!

Gerald Warner of Craigenmaddie, one of Britain’s greatest living journalists, now has a splendid blog over at the Daily Telegraph called Is It Just Me? I am sure you will all want to take a look at it. Already he has an appreciation of the recently deceased Franz Künstler, until his death the last living soldier of the Hapsburg army, a brief missive pointing out how terribly un-British the idea of a “Britishness Day” is, and a forthright post on the value of the stiff upper lip in times of crisis.

Gerald Warner of Craigenmaddie, one of Britain’s greatest living journalists, now has a splendid blog over at the Daily Telegraph called Is It Just Me? I am sure you will all want to take a look at it. Already he has an appreciation of the recently deceased Franz Künstler, until his death the last living soldier of the Hapsburg army, a brief missive pointing out how terribly un-British the idea of a “Britishness Day” is, and a forthright post on the value of the stiff upper lip in times of crisis.

Much of what Gerald says is, to sensible people, simply obvious. But one of the great dangers of our modern age is that what ought to be simply obvious is becoming less and less so due to deliberate obfuscation by the political and media classes. Gerald’s talent is that he tells you what’s what and that he manages to do it with a graceful alacrity, and often wit, that are a welcome — and, sadly, rare — treat. Go, read, enjoy!

Warneriana: Gerald Warner Axed | ‘The Mass of All Time answers that need’ | Martyrs of Spain, Pray for Us! | Warner on the Gotha

The life & death of The European

An idea before its time or the mad dream of a master swindler?

The inception of The European at the dawn of the 1990s was emblematic of the age. Triumphant scenes of joyful crowds tearing down the Berlin Wall in 1989 sparked exhilaration across the continent and the high spirits from the fall of the Iron Curtain were transformed into Euro-phoria as the ideal of a ‘United States of Europe’ now seemed a very real possibility. The media and publishing magnate Robert Maxwell vigorously supported ‘the European ideal’ and founded The European newspaper to act as a cheerleader for that ideal. Rolling from the printing presses within a year of the Wall’s fall, the newspaper had nonetheless folded by the time the Amsterdam Treaty was ratified in 1999 despite the continued growth in the size and power of European institutions. But the story of the rise and fall of Maxwell’s newspaper — the life and death of The European — is itself indicative of the strengths and weaknesses of the European project itself.

Robert Maxwell’s euro-enthusiasm might be explained by his transnational roots. “Captain Bob” (as Private Eye labeled him) was born Ján Ludvík Hoch in 1923 into a poor Jewish family in a small town in Carpathian Ruthenia — then in Czechoslovakia, now in the Ukraine — and escaped to Great Britain in 1940. He entered the British Army shortly thereafter as a private but his natural intelligence and gift for languages meant that by the war’s end he was a captain, having also been awarded the Military Cross for gallantry.

Using the many contacts he had made amongst the Allied occupation officials, Maxwell went into business as the British and American distributor for Springer Verlag, a German scientific publishing firm. In 1951, he went into publishing on his own when he purchased Pergamon Press, a textbook-printing subsidiary, from Springer Verlag, turning the company around and making handsome profits from the endeavour. A socialist, despite his business acumen, he was elected to the House of Commons in 1964 on the nomination of the Labour party, losing his seat six years later.

Through Pergamon Press, he gradually began accumulating media interests. He lost the battle to buy the News of the World to Australia’s Rupert Murdoch, who duly emerged as his arch-nemesis. By the middle of the 1980s, however, Maxwell owned the London-based Daily Mirror and Sunday Mirror, the Daily Record and the Sunday Mail (both Scottish), as well as other newspapers, a number of publishing houses, a record label, the Berlitz language schools, and half of MTV Europe, and the Oxford United Football Club.

But conventional newspapers, no matter how numerous, did not satisfy the massive ego which had become one of Maxwell’s most notorious characteristics. In June 1988, he began planning for a transnational, pan-European daily newspaper, The European, printed in colour with articles in English, French, and German. Maxwell was a keen proponent of European integration and saw the new title as a method of bridging the gap between Britain and the Continent, as well as hoping that it would act as a counterweight to the well-established American weeklies Time and Newsweek.

Maxwell brandishing issue No. 1 of The European

Maxwell’s ideal for the newspaper proved impossible to realize immediately, and when The European finally emerged on newsstands in May, 1990, it had been brought down in scope to an English-language weekly newspaper. The title emblazoned across the top — with an emblematic white dove hovering above the continent, a copy of the newspaper firmly clasped in its beak — the first copy of The European proclaimed it would bolster ‘the supporters of the integration of Europe’. Divided into three sections — the main news section, Business, and a tabloid-sized culture review named Élan — the paper made a bold use of colour long before most other broadsheets converted from black-and-white.

One million copies of the first issue were printed by Maxwell, with a guarantee to advertisers that the weekly would settle down in six months with a circulation of at least 225,000. Three months after the launch (July 1990), Maxwell claimed a circulation of 340,000 for his pet project, divided between 187,000 in Great Britain and 153,000 on the Continent. The first audited sales figure, however, came out in February 1991 with 226,000, below Maxwell’s promise to advertisers. That month, Maxwell replaced the founding editor, Ian Watson, with John Bryant, who had edited the acclaimed Sunday Correspondent during that newspaper’s brief existence.

As the sales figures continued to settle downwards, Maxwell grew less comfortable with realistic circulation estimates and he began a number of schemes aimed at driving up the numbers. That February, it was decided that ‘significantly different’ U.K. and overseas versions would be printed. In October 1991, just a few months later, Maxwell attempted to introduce an edition specific to North America, where officially 15,000 copies of the U.K. edition were sold each week. By the end of the month, however, the scheme was abandoned, and many of the hacks in The European‘s London headquarters were reduced to working a three-day week to cut corners, while some were made redundant outright.

The European aside, Maxwell’s empire was coming apart at the seams. High interest rates and a general recession were bad for business overall, but investigations had been launched into various dodgy business practices throughout Maxwell’s companies. Profits had been overstated while losses were hidden away. Money had been looted from corporate pension funds to prop up entities personally owned by Maxwell and to artificially inflate share prices. The London Metropolitan Police were even compiling a file on Maxwell’s war years, towards the aim of charging him with war crimes for killing at least one German civilian.

On November 5, 1991, Robert Maxwell disappeared from his super-yacht sailing off the Canary Islands, and his body was found floating in the Atlantic shortly afterward. Officially ruled an accidental drowning (the more imaginative claimed he was murdered), most assumed that “Captain Bob” had taken his own life rather than face the unravelling of his business empire and its supportive web of deceit. Maxwell was buried five days later on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, with Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir delivering the eulogy.

Ian Maxwell, the paper’s chief executive and son of the dead proprietor, announced to the assembled staff the true extent of his father’s crimes and their consequent impact for the newspaper, bursting into tears before making a quick exit from the newsroom. Not only were the various Maxwell operations suddenly and very seriously bankrupt, but it became apparent that Maxwell had continually fiddled with the newspaper’s circulation figures. “Rumour had it,” wrote one editor, Richard Holledge, “that copies were being burnt by that year’s particular brand of rioting French” outside the continental print site in Beauvais, and “[t]heir charred numbers were added enthusiastically to the figures”. “A better rumour,” bearing in mind Maxwell’s end, Holledge continued, “was that copies were shipped across the Channel, lost overboard and also added to the circulation”.

Bereft of its chief architect and founder, it was widely thought that The European would have to call it a day and cease operations. The remaining staff held a raucous Christmas party, presuming it would be the last undertaking of ‘Europe’s national newspaper’. But the party was far from over. Deputy editor Charles Garside, an old hand with experience in many a Fleet Street newsroom, bought the title and organised the staff, who worked without pay over the Christmas holiday in order to keep The European alive long enough until a suitable owner could be found. On one of the first weekends of 1992, Garside flew to Monte Carlo, returning the following Monday with new proprietors for The European: the famously reclusive Barclay brothers.

Identical twins, David and Frederick Barclay first made their money with a hotel they expanded into a chain and were not previously involved in the media. Under the Barclay regime and with Garside at the editorial helm, the aim was not so much to advance The European, as it was under the circulation-mad Maxwell, but to stabilise the title. With growth in sales in France, Germany, and Spain, the newspaper brought back Élan, its third section which had been suspended while the paper was losing £1 million a month. By the end of the year, the circulation appeared stable at 200,000.

As 1993 dragged on, however, the circulation dropped by at least 20,000. By August, fourteen members of staff were sacked and a plan was made to move The European into a more upmarket niche. A month later, Garside resigned and was replaced by the long-time managing editor Herbert Pearson. Pearson was immediately undermined when the Barclays’ managing director Greg MacLeod secretly prepared a magazine version of The European with a greater emphasis on features and analysis. The Barclay brothers, known for being hands-off proprietors, expressed little interest in the MacLeod project. MacLeod made his exit and Garside promptly returned as editor in June of 1994.

All continued as per usual until October 1996 when the Barclays appointed the former Sunday Times editor Andrew Neil as editor-in-chief of the Barclays’ three newspapers: The European and the two Scottish titles, The Scotsman and Scotland on Sunday, which they had bought a year before. Soon after, and surprisingly to the staff, Garside quit as European editor and Neil took over that responsibility too, with Herbert Pearson acting as the day-to-day head honcho. Andrew Neil brought new ideas to reinvigorate the paper but the perennial plan to turn upmarket finally materialized in 1997. The European was transformed into a high-end tabloid-sized colour magazine from June 1997 before it emerged in its final magazine form in March 1998.

But the Barclays were at the end of their tether. The European had lost £50 million since they took it over in 1992, and through the many trials and transformations its circulation failed to stabilise and continued its decline. By the middle of 1998, the Barclays threw in the towel and put The European, with Gerald Malone now at the editorial helm, up for sale. In September, it was announced that, unless a buyer was found, the paper would be wound down over the next ninety days. While there were hopes for an eleventh-hour savior in the form of Time Warner, and then Bloomberg, neither conglomerate made an offer. The final number of The European came out on December 14, 1998.

What then was the cause of The European‘s downfall? While it may seem strange that ‘Europe’s national newspaper’ faltered during the decade that witnessed the greatest leaps in European integration, the title was beset by such a multitude of problems from the very start that one might very well ask the question how it survived so long.

While undoubtedly the driving force behind The European, Robert Maxwell, with his erratic disposition, was a problem in and of himself. The unreliability of the paper’s circulation figures, actively fudged by ‘Captain Bob’, made advertisers think twice before investing part of their marketing budget. Maxwell’s problematic nature culminated in the massive financial scandal that rocked his empire, finalized by his mysterious death at sea. That the newspaper survived the death of its animating spirit so soon after its foundation is testament to the people who were determined to keep The European alive.

The commercial end of the newspaper’s operation was always a source of woe. Maxwell had been obsessed with newsstand circulation and so The European was one of the few newspapers that was actually more expensive to subscribe to than to buy from a newsagent — a factor which was unhelpful in building a loyal readership.

Starting a newspaper aimed at the middle-market at a time when that market is abandoning the printed media was doubtless an insolvable conundrum. The most obvious solution was to reorient the newspaper upmarket and find a suitable niche, but that too was already well taken care of by the Financial Times, the Economist, and the Wall Street Journal.

Distribution, meanwhile, was “an impenetrable mystery” according to Gerald Malone, the paper’s final editor. “I could never buy it in [the London Borough of] Wandsworth, but without fail found a copy in the village shop in Earlston, a tiny community in the Scottish Borders.”

Malone also claimed The European‘s staff was somewhat inconsistent in ardour. Mixed amongst the “hardworking young talent” and the “corps of professionals who brought the paper out through thick and thin” were “prima donnas” and “opinionated misfits past their sell-by date”. “In fact,” Malone wrote after the newspaper’s demise, “they were Fleet Street’s finest freeloaders: old-style fat-cats paid prodigious sums, in one case £75,000 for a three-day week”.

“One senior editor, who carped when I complained that the newsroom often resembled the aft deck of the Mary Celeste, resigned minutes before I could sack him, resenting my outrageous demand that he spend a bit more time in the office and forego long, boozy lunches fuelled with with Bulgarian wine.”

These practical problems aside, The European suffered a debilitating schizophrenia from birth. It claimed to be a European newspaper published in English but it was viewed more as a British newspaper reporting on European affairs. Maxwell’s stated aim (“Barking mad,” according to Malone) was to produce a newspaper for “the housewife in Toulouse”. But the Tolosanian housewife was already well catered for by the media of her own country, printed in her own language.

With institutional schizophrenia, a host of distribution problems, a staff of “freeloading prima donnas”, and the disappearance of its founder into the murky depths of the sea, it is indeed surprising that The European managed a good eight years in print. But besides all these there remained a never-solved existential dilemma at the heart of The European — “Europe’s national newspaper” — that it was impossible to be the national newspaper of a nation that doesn’t exist.

How a newspaper should look

The Sunday edition of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung has always been a handsome newspaper. I admired its appearance so much that it provided much of the inspiration for the look of the Mitre during my editorship of that august publication. The weekday FAZ was famously reactionary in forbidding the appearance of photographs or any colour on the front page, so the Sonntagszeitung was viewed as an opportunity to be a bit more colourful and a little more free, but still within a solid traditional design.

It saddened me to learn that the Monday-through-Thursday FAZ has given in to the Spirit of the Age and now allows not only colour on its front page but photographs there as well. It now looks like a fairly conventional German newspaper, rather than the king of German dailies.

I will miss the old black-and-white FAZ because for me it brings back memories of visits to Dr. Timmerman‘s flat in St Andrews. Sofie and I used to go over to the good professor’s place for German pancakes on Shrove Tuesday (or to listen to his giant old radio, or to simply enjoy good conversation with good wine) and he had a massive pile of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitungs which I believe he only discarded at the end of the month.

Because the Frankfurter Allgemeine‘s front page is now a little less boring, the world in general is now a little less interesting.

‘Flying High’

[I came across this piece by Taki whilst trawling through the Cusack archives, and I thought now would be the appropriate time to share it.]

By Taki Theodoracopulos (The Spectator, 22 April 2006)

Do any of you remember a film called The Blue Max? It is about a German flying squadron during the first world war. A working-class German soldier manages to escape trench warfare by joining up with lots of aristocratic Prussian flyers who see jousting in the sky as a form of sport, rather than combat. Eager for fame and glory — 20 confirmed kills earns one the ‘Blue Max’, the highest decoration the Fatherland can bestow — the prole shoots down a defenceless British pilot whose gunner is dead. His squadron leader is appalled. ‘This is not warfare,’ he tells the arriviste. ‘It’s murder.’

I know it’s only a film, and a Hollywood one at that, but jousting in the air was a chivalric endeavour back then, with pilots who crash-landed behind enemy lines being treated as honoured guests before being interned for the duration. The man who embodied all the chivalric virtues was, of course, Manfred von Richthofen, whose family had been ennobled by Frederick the Great in the 1740s. When Baron Richthofen became a fighter pilot in the late summer of 1916, it was still only 13 years since the first flight of Orville Wright. The technique of applying air power to warfare was barely understood. One looped-the-loop, and pilots who managed to shoot down enemy aircraft and survive were regarded as heroes and quickly accumulated chestfuls of medals. When the Red Baron (his plane was painted a dark red, hence the nickname) died on 21 April 1918, the Times for 23 April devoted one third of a column to England’s fallen enemy, remarking that ‘all our airmen concede that Richthofen was a great pilot and a fine fighting man’.

By the time of his death, the Red Baron had notched up 80 victories, a record, with the leading French ace, René Fonck, claiming to have shot down 157 German aircraft, but only 75 being confirmed. (Rather French, that.) Needless to say, the mystery surrounding Richthofen’s death added to his legend. No one knows for sure who shot him down, or even if the bullet which killed him came from the ground. The English who found his body treated it with all the ceremony they would have accorded one of their own. An honour guard escorted the corpse to his own lines and British pilots overflew and dipped their wings. Those were the days. Out of 8 million men of his generation who died in that useless war, Richthofen’s is among the few names which will most likely be remembered by the general public on the 200th anniversary of his death.

His brother Lothar and his cousin Wolfram (who bombed Stalingrad 25 years later, and was one of Hitler’s favourites) flew alongside the baron, establishing a tradition for excellence and gallantry in the Luftwaffe. The second world war saw great heroics by German pilots, starting with Hans Ulrich Rudel, with something like 400 Stalin tanks to his credit, Adolf Galland, Erich Hartmann, who shot down 352 Soviet aircraft in the course of 1,500 missions, and Walter Novotny, with 250 Soviet aircraft in fewer than 450 missions.

My favourite is, of course, Prince Heinrich Sayn-Wittgenstein, whose heroics overshadowed the rest, and whose plane was shot down at the very, very end of the war in Schonhausen, the Bismarck home. Wittgenstein had his crew bail out first but was unconscious when he hit the ground. He had been hit while in the cockpit. By the end of the war he had become such an ace and legend he could do what he pleased. He once flew a combat mission with a raincoat over his dinner jacket. A few days before he had been to Hitler’s headquarters to receive the Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross. He told the beautiful Missie Vassiltchikov on the telephone, ‘Ich war bei unserem Liebling’ (I have been to see our darling) and added how surprised he was his handgun had not been removed before he entered ‘the Presence’. Heinrich would have loved to have bumped him off, but by then Germany was ruined and the prince died three days later. Hitler had many heroic pilots grounded towards the end, but Wittgenstein, being noble, was kept flying.

Why am I bringing all this up in the year of Our Lord 2006? As I told you last week, while down in Palm Beach, a friend of mine, Richard Johnson, tied the knot with Sessa von Richthofen, and I flew down a group of friends for three days of non-stop celebrations. The couple exchanged vows on an 80-year-old river boat which plies its trade in the inland waterway which crisscrosses Florida. My speech went down great, but then some ghastly paparazzo by the name of Harry Benson went around complaining about it. Never to me, needless to say, otherwise one more kill would have been added to the Richthofen legend.

“Der Rote Baron”

Foreign Film Fictively Frames Favorite Fabled Freiherr

Our cunning cousin, the Hun, has cleverly concealed a card up his hunting-jacket sleeve. Just when you thought the continual winging by hand-wringing Germans about their militarist past (or at least the thoroughly shameful parts thereof) would never end, a new film depicts the life of the dashing Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen: better known to us as The Red Baron.

Our cunning cousin, the Hun, has cleverly concealed a card up his hunting-jacket sleeve. Just when you thought the continual winging by hand-wringing Germans about their militarist past (or at least the thoroughly shameful parts thereof) would never end, a new film depicts the life of the dashing Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen: better known to us as The Red Baron.

“Der Rote Baron” is showing in den deutschen Kinopalästen as we speak, but the motion picture was not actually meant for a German audience: this is but part of the clever ruse. The film was actually made in English and then dubbed back into German by the mostly Allemanic cast.

Having convinced us of their peaceful intentions through more than a half-century of “Guys, we really messed up circa 1933-1945”, the obvious intent is to swamp the English-speaking world with a film depicting the charming gentlemen fighters of the first weltkreig in order to disarm us as they prepare for their dastardly plans.

Why, as we speak, Georg Friedrich von Preussen is polishing his pickelhaube and dusting off his feather cap in preparation for this latest Prussian plot for world domination. While the Western world worried itself sick over global Islamism and the Chinese threat, little did we know that a swelling irredentism was brewing deep within the hearts of every Berliner; a tear developing in the eye at the mere mention of Tsingtao; a soul in mourning for the loss of Tanganyika. How naïve we were not to realize that all those bright young Germans spending their gap year teaching smiling Herero natives in Namibia were actually forward units of intelligence-gatherers yearning for the return of Ketmanshoop and Swakopmund to the Germanic fold.

Abomination

This act of willful cultural vandalism is noxious in the sight of both God and Man and is a complete and utter abomination. Whoever is responsible for this should be hanged, drawn, and quartered, and buried at a crossroads with a stake through his heart.

Observe the beauty of this building at the corner of Harrison & Penn in Williamsburg, Brooklyn: its classic composition, its complete vernacular ease. And look at the cheap, tawdry, wrongly-colored brick used to hide and ultimately destroy this ordinary gem.

How can the perpetrator of this act sleep at night? It boggles the mind…

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai

Als alle Knospen sprangen,

Da ist in meinem Herzen

Die Liebe aufgegangen.

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai,

Als alle Vögel sangen,

Da hab ich ihr gestanden

Mein Sehnen und Verlangen.

The Other Modern

An Architecture of Continuity:

Luis Moya Blanco’s Universidad Laboral de Gijón

In 1944, an undersecretary of Francoist Spain’s Ministry of Labour visited the city of Gijón to attend the funerals of a group of miners killed in a mine collapse. After the solemn rites took place, Turiño Carlos Pinilla met with a group of locals filled with concern for the offspring of the dead workers. All they asked of the bureaucrat was an orphanage; what they ended up with ten years later was a magnificent palace of charity, almost a city unto itself and the largest building in Spain: the Universidad Laboral de Gijón.

An example of Catholic social teaching (which upholds the essential dignity of work and the working man), the “labor university” was founded as a secondary-level institution to teach vocational and technical skills to the children of Spain’s working class. At over 2,900,000 sq. ft. of space, it is more than double the size of the great Royal Monastery and Palace of El Escorial built by Phillip II in the sixteenth century, and was accompanied by over 380 acres of farmland.

The goal was to accommodate 1,000 students (eventually doubling) from the age of 12 to 16, with residences, school facilities, industrial workshops, working farmland, athletic facilities, and sporting fields. The educational aspect and leadership of the Laboral was entrusted to the Jesuits, while the Poor Clares also had a convent on the premises, performing various household tasks and caring for the girls as their particular charism. (more…)

Q&A: Lady Cochrane Sursock

In a fascinating interview, Canadian journalist and Monocle editor-in-chief Tyler Brûlé talks with Lady Yvonne Cochrane, “doyenne of the Christian East”, discussing Beirut past, Beirut present, and Beirut future.

Update: She is actually Yvonne, Lady Cochrane Sursock, not Lady Yvonne Cochrane as Monocle styles her. Hat tip to Mr. Bond.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories