Arts & Culture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

How bad journalism infects religion reporting

Tom Kington & Jamie Doward of The Observer lead the way

“Pope stirs up Jewish fury over bishop: The Vatican is reinstating a British priest who denies millions died at the hands of the Nazis. … Tension between the Vatican and Jewish groups looked set to explode yesterday after Pope Benedict XVI rehabilitated a British bishop who has claimed no Jews died in gas chambers during the second world war.”

Or rather, not. All the Holy Father has done is lift Bishop Williamson’s excommunication. Bishop Williamson’s excommunication had nothing to do with his holocaust denial, but rather with his willful disobedience to authority. Thus the lifting of his excommunication is in no way a “rehabilitation”, nor an endorsement of his dodgy views on history, but merely to do with the offense or state which brought about excommunication.

For some reason, this kind of misleading disinformation (whether out of malicious intent or just not being very good at one’s job) infects religion reporting more than any other field in the British media. You would think people would study or learn about the institutions they report about, but that no longer seems a requirement of the job as it presumably once was. Go figure.

Passenger Ship Chapels

Above & below: the SS Normandie. The Normandie was seized by the U.S. government and renamed the USS Lafayette but burned in New York harbor before she could be put to good use in the war effort. The bronze doors to the chapel were salvaged and now grace the Church of Our Lady of Lebanon in Brooklyn.

South Africa

I‘m afraid that blogging may be lighter than usual for the next few months, as I have gone into voluntary exile in South Africa. Internet access can be a bit tricky deep in the verdant winelands of the Western Cape, but I will certainly endeavour to send a few updates, not to mention some of the usual variety of posts (a number of which are currently cooking in the oven). It’s a rather handsome town I’m in, as this page shows.

Berlin to build ersatz Stadtschloß

Afraid of celebrating glorious past, a horrible future is created instead

Fresh from the glories of Dresden’s rebuilt Lutheran Frauenkirche, the city fathers of Berlin have decided to reconstruct the old Stadtschloß (“City Palace”) at the heart of the German capital, only not quite. Largely ignored by the anti-monarchist Nazis, the original Stadtschloß was damaged by Allied bombing and by shelling during the Battle of Berlin before the Communist government of East Germany demolished it entirely and built the horrendously ugly Palast der Republik (housing the Soviet satellite’s faux parliament) on the site. The Communist monstrosity has finally been demolished, but the authorities decided that, rather than restore the beautiful royal palace that once stood on the site, they will instead merely replicate three of the old structure’s façades, leaving one of the façades and most of the interior in a modern style.

Dublin (In the Rare Old Times)

O’Connell Street, Dublin, United Kingdom of Great Britain & Ireland.

West End Collegiate Church

One of my good friends, who is amongst the most loyal denizens of this little corner of the web, found our post on St. Nicholas Collegiate Church of great interest because his son attended the Collegiate School, the oldest school in North America (founded in 1628, and formally incorporated ten years later). The Collegiate School is part of the same complex as the West End Collegiate Church on the corner of West End Avenue & 77th Street on the Upper West Side. The church & school buildings were designed by McKim Mead & White in a Dutch Renaissance Revival style, and handsomely executed.

One of my good friends, who is amongst the most loyal denizens of this little corner of the web, found our post on St. Nicholas Collegiate Church of great interest because his son attended the Collegiate School, the oldest school in North America (founded in 1628, and formally incorporated ten years later). The Collegiate School is part of the same complex as the West End Collegiate Church on the corner of West End Avenue & 77th Street on the Upper West Side. The church & school buildings were designed by McKim Mead & White in a Dutch Renaissance Revival style, and handsomely executed.

THE ARCHITECTS modelled the church after the seventeenth-century Vleeshal (meat market) of Haarlem in the Netherlands. The story goes that, during the Second World War, a handful of Collegiate grads serving together in the U.S. Army participated in the liberation of Haarlem, stumbled upon the Vleeshal and said “Hey, that’s our school!”

New York’s Dutch Cathedral

The Collegiate Church of St. Nicholas, Fifth Avenue

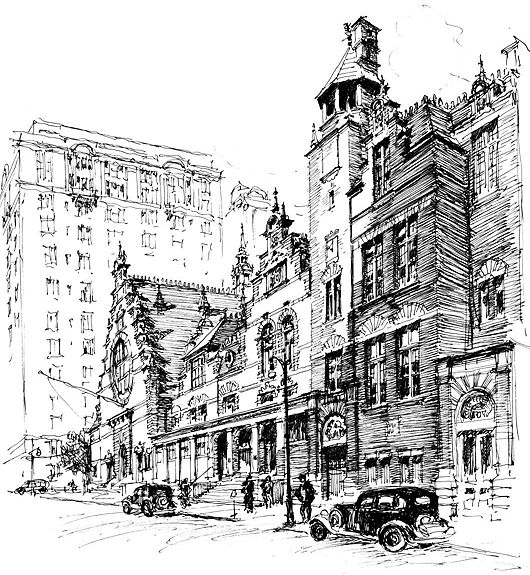

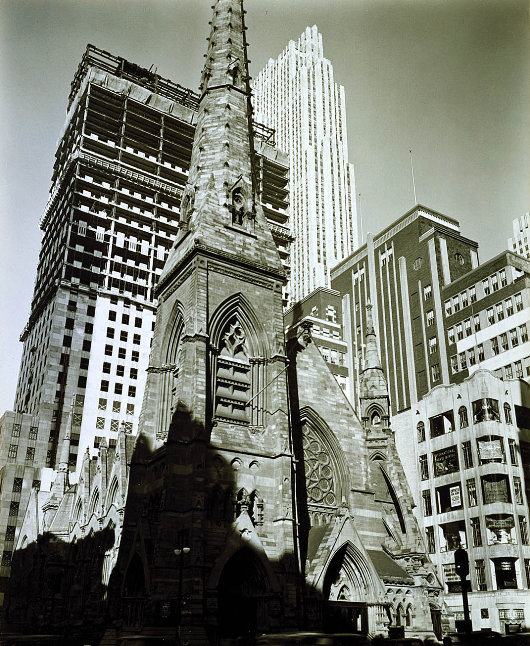

Dedicated a hundred-and-thirty-six years ago, the Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church of Saint Nicholas on the corner of Forty-eight Street & Fifth Avenue (photographed above by Berenice Abbott) was for many years regarded as the most eminent Protestant church in New York. The Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church is the oldest corporate body in what is now the United States, having been founded at the bottom of Manhattan in 1628 and receiving its royal charter from William & Mary in 1696. Now part of the Reformed Church of America, the Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church is actually a denomination within a denomination, and the remaining Collegiate Churches of New York tend to preach a sort of “Christianity Lite”. (The famous Norman Vincent Peale, author of The Power of Positive Thinking and one of the paragons of the “finding a religion that doesn’t interfere with your lifestyle” school of thought, was the pastor of Marble Collegiate Church at Twenty-ninth & Fifth, where Donald Trump is a member of the congregation).

Peter Stuyvesant’s Legion

Oil on canvas, 30 in. x 80 in.

1953, Jacob Ruppert Brewery

An Aside: I was taught Latin beside the beautiful carved marble fireplace in the artist’s dining room. Winter lived next door to the school, which purchased the house after his death and used it for class rooms. In our more neglectful hours which investigated the basement, in which were still secreted some of the artist’s sketches for larger murals and models for a bas-relief.

67th & Fifth

One of the most remarkable things about these photos from a 1956 Seventh Regiment ceremony are how traditional the buildings in the background are.

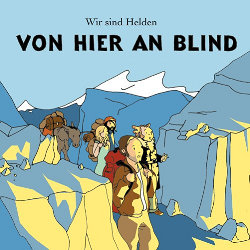

Von hier an blind

The German band “Wir sind Helden” is a quartet purveying inoffensive pop rock, and recommended to us by one of our continental cronies. For their 2005 album cover, Von hier an blind, the band commissioned a group portrait in the ligne-claire style. The design is an obvious homage to Hergé’s Tintin. “Wir sind Helden” are little-known in the English-speaking world, though they have played three sold-out concerts in London, and are available from the iTunes Music Store.

The German band “Wir sind Helden” is a quartet purveying inoffensive pop rock, and recommended to us by one of our continental cronies. For their 2005 album cover, Von hier an blind, the band commissioned a group portrait in the ligne-claire style. The design is an obvious homage to Hergé’s Tintin. “Wir sind Helden” are little-known in the English-speaking world, though they have played three sold-out concerts in London, and are available from the iTunes Music Store.The Pester Lloyd

The Hungarian capital’s German-language newspaper has been “independent, pluralistic, steeped in tradition” since 1854

The fall of the Iron Curtain nearly twenty years ago after a half-century of Communist domination in Eastern Europe afforded an opportunity to revive many of the traditions and institutions which — while they had survived monarchy, republicanism, and fascism — were annihilated by the all-consuming Red totalitarianism. One such institution that has risen from the ashes is Hungary’s once-revered German-language newspaper, the Pester Lloyd.

First appearing in 1854, when Buda and Pest were still two cities flanking the banks of the Danube, the Pester Lloyd was the leading German journal in Hungary. Printed daily with morning and evening editions, the “Pester” in the paper’s name refers to Pest, while “Lloyd” is in imitation of Lloyd’s List (the London shipping & commercial newspaper founded in 1692 by the eponymous properitor of Lloyd’s Coffee Shop and still going strong today). The paper first gained prominence under the editorial leadership of Dr. Miksa (Max) Falk, who had famously tutored the Empress Elisabeth in Hungarian and instilled in the consort a particular love for the Hungarian kingdom.

First appearing in 1854, when Buda and Pest were still two cities flanking the banks of the Danube, the Pester Lloyd was the leading German journal in Hungary. Printed daily with morning and evening editions, the “Pester” in the paper’s name refers to Pest, while “Lloyd” is in imitation of Lloyd’s List (the London shipping & commercial newspaper founded in 1692 by the eponymous properitor of Lloyd’s Coffee Shop and still going strong today). The paper first gained prominence under the editorial leadership of Dr. Miksa (Max) Falk, who had famously tutored the Empress Elisabeth in Hungarian and instilled in the consort a particular love for the Hungarian kingdom.

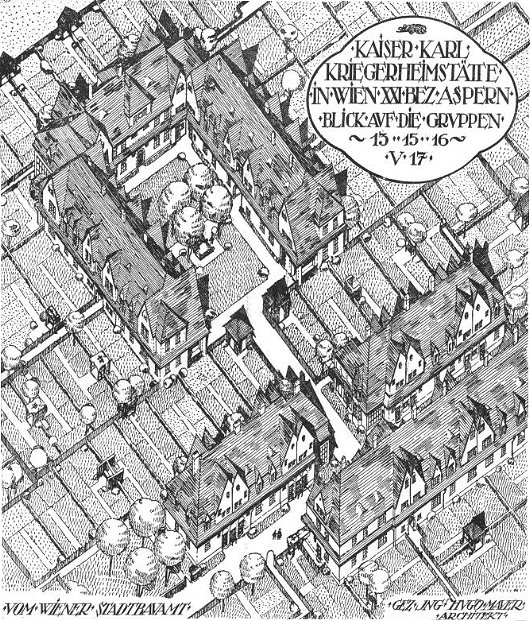

The Kaiser Karl Soldiers’ Homes

An unexecuted design. The architect later designed a number of housing projects during the First Austrian Republic.

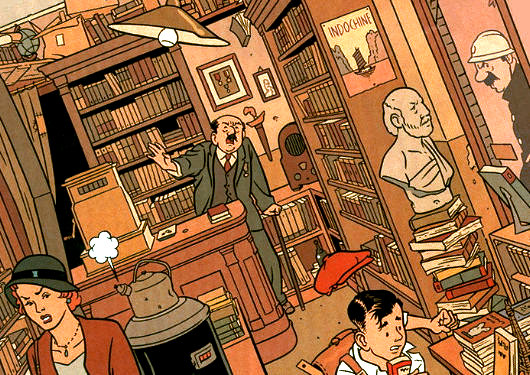

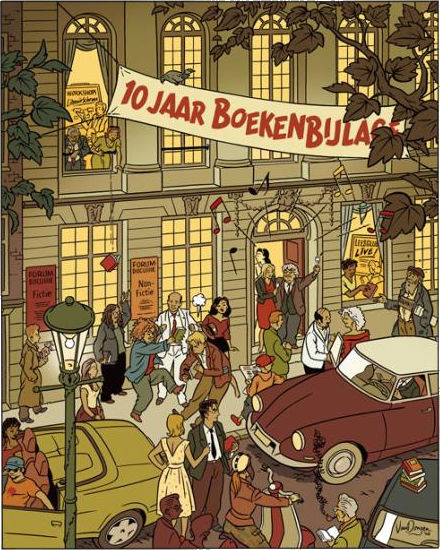

Peter van Dongen

Dutch champion of the Ligne Claire style

No doubt one of the most enjoyable aspects of Hergé’s great Tintin series of bandes desinées is the brilliant ligne claire style in which they are drawn; the most talented living exponent of which is surely Peter van Dongen. This Dutch striptekenaar (“comic-strip draughtsman”) first came to the attention of the comic world in his mid-twenties with Muizentheater (1990), a tale of two working-class Amsterdammers growing up during the Great Depression. As van Dongen despises clichés, it is one of the few books about Amsterdam that doesn’t feature a single canal. It was nearly ten years before van Dongen produced his second comic work, Rampokan, depicting the Dutch East Indies during their final years before independence. (On Rampokan, van Dongen collaborated with fellow ligne-clairist Joost Swarte, whose work is often seen in The New Yorker).

Van Dongen works as a commercial illustrator, and he often provides illustrations for NRC Boeken, the book review of the NRC Handelsblad. A celebration of the tenth anniversary of NRC Boeken was held at the Felix Meritis and is commemorated in the drawing above.

The New York Central Building

The New York Central building once presided majestically over an equally elegant Park Avenue, which is cleverly directed through the building from the south, emerging through the double arches on the north side. Sadly, while the tower (now known as the Helmsley Building) still stands, the view of it has been marred since 1963 when the Pan Am building was built between it and Grand Central Terminal. When it opened, the Pan Am building was the largest commercial office building in the world, and it was certainly one of the least graceful. The 1960s and 70s were not kind to Park Avenue on either side of Grand Central, and many of the traditional-style buildings have been demolished or re-clad in glass.

Russia Turns a Cinematic Page in History

Big-budget film celebrating anti-Communist hero & White Russian leader Admiral Kolchak is partly funded by Russian government

Here’s a film that has it all: naval battles, mutiny, revolution, civil war, brave men, beautiful women, sin, sacrifice, and betrayal on multiple levels. But “Admiral” («Адмиралъ»), which opened in Russia this month, is notable for another reason: this is the first major film depicting the tsarist White Russians as the good guys to receive at least part of its funding from the Russian government. The eponymous hero of the film is Alexander Kolchak, the naval commander and polar explorer who later led part of the White Army fighting the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories