Arts & Culture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Scottish Executive, 1999-2007

While naturally relieved that Labour are no longer in charge, one of the few objections I have to the current SNP government in Scotland is that they changed the name of the Scottish Executive to “the Scottish Government”. The new name is just so damned boring. Every country, region, town, and borough has a “government”; it’s the dullest word you can come up with. But “the Scottish Executive” had such a nice ring to it. Listening to the evening news on Radio Scotland, one heard the newsreader speak of “the Scottish Executive” and immediately thought “Ah yes, that’s our part of the government!” Now one hears the sultry phrase “The Scottish Government today announced new measures…” and thinks “Oh, the government. Nobody likes the government.”

To add to this lamentable change, they even dumped the Scottish coat of arms as the visual identity of Scotland’s authority (as seen above, in the Executive days) and replaced it with an exceptionally dull saltire-flag logo that can be seen on the Scottish Government’s website.

Premier Salmond, give Scotland back her heraldry!

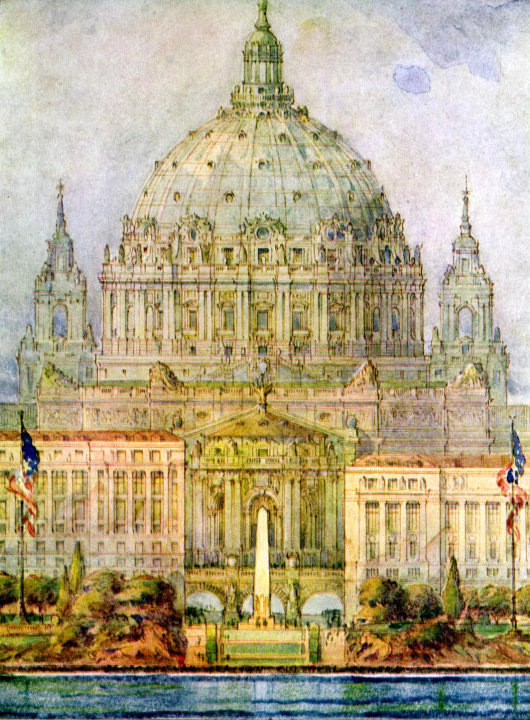

Riparian Architecture

I’m not entirely sure of what project this is an architectural rendering, but I suspect it is an unbuilt project designed by Cass Gilbert for Blackwell’s Island in the East River, later known as Welfare Island and now Roosevelt Island. There were a number of schemes before the First World War (Thomas J. George was the author of one) for the construction of a new civic center for New York on the island, which is located right in the middle of the five boroughs.

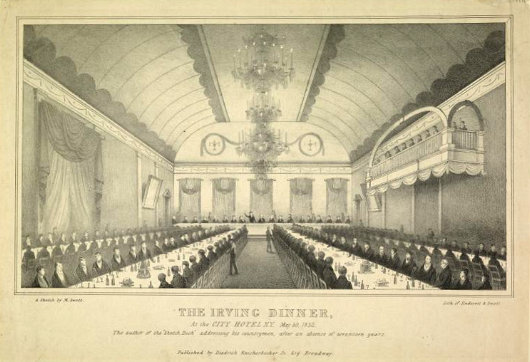

The Irving Dinner

It was slightly remiss of us to neglect commemoration of the two-hundred-and-twenty-sixth anniversary of that genius of the Knickerbockers, Washington Irving. “Diedrich Knickerbocker,” “Jonathan Oldstyle,” “Geoffrey Crayon,” or, as he was baptized, just plain Washington Irving was born on April 3, 1783, exactly five months before the Treaty of Paris established the legal independence of his home state of New York and the twelve other former colonies along the Atlantic coast.

Irving was arguably the first American celebrity, and deservedly so. After a seventeen-year exile in England, France, Germany, and Spain, the author returned to New York in 1832, and a celebratory dinner was held in his honor at the City Hotel in New York on the evening of May 30. He is seen in this contemporary picture addressing those who assembled to render him honor, many of them from among the city’s political, cultural, and social elites. Indeed, the Saint Nicholas Society was founded just three years later for the preservation of the Dutch history and customs of New York, a noble task in which it continues to this day.

The Continued Decline & Fall of the International Herald Tribune

The New York Times ‘tightens the leash’, shutting IHT website and redesigning newspaper as Times-lite; Herald-Trib loyalists cry foul

THE SAD DECLINE of one of the newspaper world’s most historic titles is continuing as the entire industry faces the challenges of the twenty-first century. The International Herald Tribune recently suffered a host of changes on the order of its proprietor, the New York Times, that have continued to assault the Paris-based newspaper’s individual identity. The paper’s website, iht.com, has been shut down and now redirects to a new portal on the New York Times‘s website, nytimes.com. Non-U.S. internet viewers are now automatically sent to the new portal — global.nytimes.com — upon accessing the Times website as well, but can switch to the U.S. edition at the click of a button. The rationalization for the move is centered on the New York Times Company’s attempts to boost online advertising revenue as print advertising and sales figures tumble. Furthermore, the actual print version of the Herald-Tribune has been redesigned, spurning the paper’s long design identity to make it look like a more light-weight version of the New York Times.

Paris Arts & American Arms

Maj. T. L. Johnson’s Cartographic Mural on Governors Island

One of the best aspects of the inter-war construction of Governors Island is that the refinement of McKim Mead & White’s architecture is matched inside by a series of interior murals painted under the auspices of the WPA. These murals often veered towards the refreshingly jocular, as can be seen in the War of 1812 mural in Pershing Hall (a corner of which is captured here by photographer Andrew Moore). The mural by Major Tom Loftin Johnson (educated at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris) depicted here, however, is a map of the area under the purview of the Second Corps, U.S. Army headquartered at Governors Island; namely the states of New York, New Jersey, and Delaware, and the then-territory of Puerto Rico.

From the provinces to power

What a change eighty years makes! What was once filed under “English Provincial Press” is now the voice, mouthpiece, and all-but-official organ of the British establishment.

A new bookplate for the NYG&B

Fr. Guy Selvester reports on his resurrected Shouts in the Piazza blog that the great Marco Foppoli has designed a new bookplate for the New York Genealogical & Biographical Society. Mr. Foppoli is the most highly-regarded heraldic artist of our day, and the influence of the style of his mentor, the late Archbishop Bruno Heim, is apparent in his work.

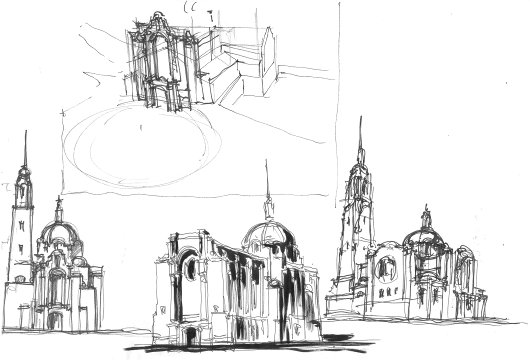

Matt Alderman’s at it again

The king of counter-proposals sets eyes on Divine Mercy shrine

Young architect Matt Alderman presents his counter-proposal to a horrifyingly kitsch proposal for a West-Coast U.S. shrine to the Divine Mercy. Why, given that the recovery of skill & talent in architecture in the past few decades, are most new churches still revoltingly ugly? “The problem is not that it is hard to get beautiful churches built, but that the wrong people seem to end up getting the commissions,” Matt writes. “Oakland and Los Angeles were, of course, going to go modernistic no matter what, but Houston Cathedral could have been a masterpiece if handled by someone with a greater openness to traditional design, rather than settling for a mediocre pseudo-traditionalism.”

Happy St. Patrick’s Day

Another view of Dublin’s splendid General Post Office on O’Connell Street; the last one we posted was from half a century earlier.

Eric Seddon on Washington Irving

Alongside Miklos Banffy, Washington Irving is probably my favourite author. I have two sets of his complete works, and will obtain at least a third — my favourite printing of the complete Irving, in an excellent handy size — when I can find it for the right price. It is curious, but by no means suprising, that Irving’s genius is nearly forgotten today even though he was the first American to be an international superstar, famed on both sides of the Atlantic. He is mostly known only through his authorship of Rip van Winkel and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, both of which works are rarely presented in their original written form, but almost always in shortened illustrated versions for schoolchildren from publishers convinced of their audience’s stupidity.

Irving is rarely in the limelight these days, but First Things Online recently published an informative article, “Washington Irving and the Specter of Cultural Continuity” by one Eric Seddon, that is well worth reading.

His first book, Dietrich Knickerbocker’s History of New York, capitalized on the amnesia of New Yorkers by a mix of biting satire and real history of the Dutch reign in Manhattan. The book is foundational to any study in American humor. It is wild, free, self-deprecatory, and merciless to the public figures of his day, and by turns lyrically funny, absurd, and reflective. Without it, we might wonder whether American humor, from Twain to the Marx brothers to Seinfeld, would have taken the particular shape it did.

When Americans, always prone to utopian daydreams, were in danger of taking themselves far too seriously, when the term “manifest destiny” was embryonic, Dietrich Knickerbocker rolled his bugged-out eyes, chuckled gruffly, and whispered into the ear of a young nation, “Remember thou art mortal.” […]

Irving’s two most famous stories are to be found in The Sketch Book, virtually bookending the text: “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” In “Rip Van Winkle,” Irving whimsically pointed out the hazards of the new Republic, that a once humble acceptance of life under monarchy could easily give way to arrogant corruption, vice, and the nauseating specter of being governed by village idiots with a gift for demagoguery. […]

The final warning of the book comes in the form of a Headless Horseman, who is either a real ghost of the Revolution or the town bully in disguise, and who targets, of all people, the schoolmaster (even small towns have their intelligentsia). Is it history chasing Icabod Crane, the puritanical teacher obsessed with stories of witch hunts, or just Brom Bones scaring him out of town? Irving doesn’t say, and perhaps our answers tell more about ourselves than about him.

Washington Irving spent his last days in Tarrytown, near the setting of his most famous story. He was a member of the local Episcopal Church, tried to revive the old Dutch festivities on St. Nicholas Day, and was moved to tears by singing the Gloria. In particular he loved to repeat the words “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, and good-will to men.” Though his era was in many ways a bigoted one, he resisted and thereby helped to shape a better future. One of his last revisions to Knickerbocker came late, removing the anti-Catholic references its youthful version contained. He was a man who had seen his share of specters, to be sure, but who didn’t believe they were the strongest reality.

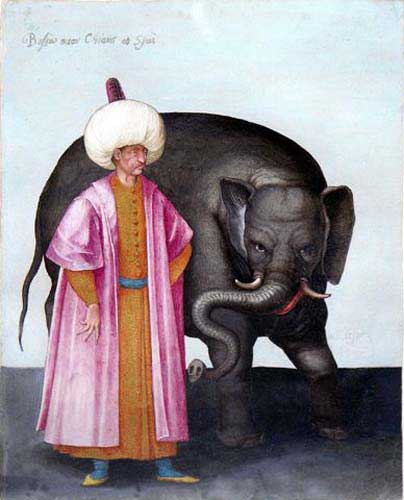

A Turbaned Pasha with an Elephant

Tempera and shell gold on paper, 10.0 in. x 8.8 in.

c. 1580-1585, Private collection (now for sale)

While known as a painter of large-scale works, a draftsman, and a printmaker, Jacopo Ligozzi — the court painter to the Grand Dukes Francesco I, Ferdinando I, Cosimo II, and Ferdinando II — also completed a series of drawings depicting Turkish traditional dress and costume. Interest in the Ottoman empire and its people increased after the great victory over the Turks at Lepanto in 1571, commemorated as a Christian feast to this day. Ligozzi never visited the Turkish realm himself but derived his inspiration for this particular illustration from the drawings accompanying the Venetian edition of Nicolas de Nicolay’s chronicle of the 1551 embassy of Henri II to the court of Suleyman the Magnificent.

That, at any rate, is the source of the Pasha; the inspiration for the elephant (of the African variety) remains undetermined. Suleyman gave an African elephant accompanied by a turbaned mahout and a staff of thirty to the future Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II, and it’s probable that Ligozzi used a printed depiction of this as a source for the picture here. (Earlier, in 1514, the King of Portugal gave an elephant named Hanno to Pope Leo X, a Medici).

This charming work, available from the Arader gallery of New York, is one from the series of tempera depictions of Turkish costume by Ligozzi, twenty of which are in the Uffizi, one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and another in the Getty Museum of Los Angeles. It was probably painted between 1580 and 1585 while the artist was in the service of Grand Duke Francesco I de Medici. Ligozzi’s depictions were first bound in a single volume in the possession of the Gaddi family before, in 1740, the manuscript reached the hands of the Manifattura Ginori de Doccia, the porcelain factory founded outside Florence in 1735 by Marchese Carlo Ginori. There, it inspired a number of porcelain platters which are today dispersed around collections worldwide. The principal group of these illustrations were donated to the Uffizi in 1867.

Un soupçon de couleur

These two numbers of the Gaullist newspaper Le Rassemblement show what even a little dose of colour can do for a journal printed in black-and-white. The lack of additional colour was due to economical, not to mention technological, restraints, but we have now gotten well used to our newspapers being printed in a full array of colour. Yes, even the FAZ.

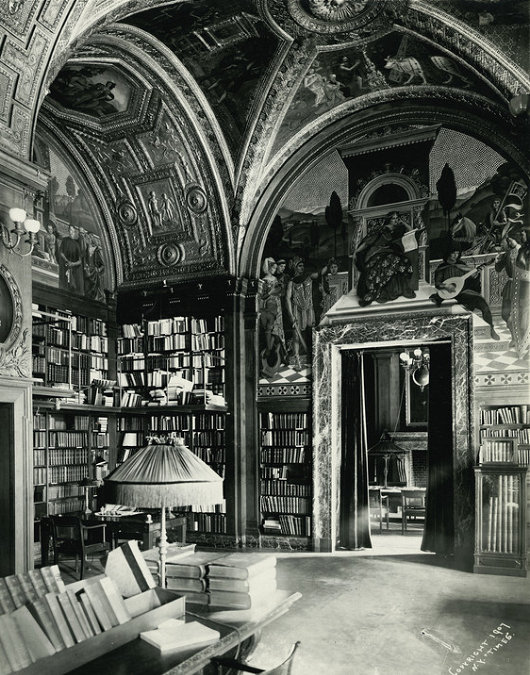

The Finest Library in All New York

Or is it in all the New World?

I do miss my two libraries in Manhattan, the Society Library on 79th Street and the Haskell Library at the French Institute on 60th. Neither of them, however, are fit to shine the boots of the library of the University Club on 54th & Fifth. Architecturally and artistically, it is undoubtedly the finest library in New York. But does it have an equal or a better in all the New World? The BN in BA certainly isn’t a competitor.

Old Radders

The devil in me, while entirely appreciative of the beauty of Radcliffe Camera, sometimes wonders if the handsome square it is in might be better off without it. What would it look like?

Wupperthal in die Wes-Kaap

Deep in the Cedarberg, in the northern reaches of the Western Cape, there is a lovely little Moravian mission in a valley called Wupperthal. Unless you have a 4×4, there is just one road in and out of the valley, and even that road can be a bit tricky for conventional vehicles. Barefoot children, smiling and carefree, play in the streets beneath the avenue of eucalyptus that perfectly frames the beautiful church. Genadendal is the most famous of the Moravian missions, but Wupperthal was actually founded by Rhenish missionaries, before briefly becoming Dutch Reformed in the middle of the last century, and then taken over by the Moravians, or Herrnhuters as they are called in Afrikaans, after the Sorbian stronghold of the Unitas Fratrum.

Russia’s Treasures on the Banks of the Amstel

Seventeenth-century Amsterdam building will, from June, be home to collections from St. Petersburg’s Imperial Hermitage Museum

A new 100,000-square-foot space displaying works from the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg will open in Amsterdam this June. The Hermitage Amsterdam will be located in the Amstelhof, a former home for the elderly built in 1683 by the Dutch Reformed Church and transformed into a modern exhibition space by Hans van Heeswijk Architects. The opening exhibition, “At the Russian Court” — a “a deeply researched exploration of the opulent material culture, elaborate social hierarchy and richly layered traditions of the Tsarist court at its height in the nineteenth century” — will display 1,800 works from the massive collection in St. Petersburg and continue until the end of January 2010.

New York Firm Tapped for Restoration of Budapest Landmark

The New York firm of Beyer Blinder Belle, responsible for the restoration of Grand Central Terminal, has been selected to develop “an adaptive reuse and restoration plan” for Exchange Place, a historic building on Budapest’s Freedom Square (Szabadság tér). Exchange Place was built in 1905 for the Budapest Stock and Commodities Exchange, and includes a number of ornamental details in the Hungarian style of the Secession architectural movement. After the Soviet conquest of Hungary, the building became the Lenin Institute before being given over to the state television broadcaster.

First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry

Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on white laid paper, 9 in. x 7 1/4 in.

c. 1811-1813, Rogers Fund

Previously: The Prince of Wales in Philadelphia

Some Afrikaners

“In my father’s shop,” writes the photographer David Goldblatt, “serving Afrikaners, I found, almost in spite of myself, that I liked many of them and, to my surprise, that I was beginning to enjoy the language. There was a warm straightforwardness and an earthiness in many of these people that was richly and idiomatically expressed in their speech. And, although I have never advanced beyond being able to speak a sort of kombuistaal, I delighted in our conversations. Yet, withal, I was very aware that not only were most of these people Nationalists, strong supporters of the Party and its policies, but that many were racist in their very blood. Although anti-Semitism was now seldom overt, they made no secret of their attitude to blacks, who at best were children in need of guidance and correction, at worst sub-human. I was much troubled by the contradictory feelings of liking, revulsion, and fear that these Afrikaner encounters aroused in me and felt the need somehow to come closer to these lives and to probe their meaning for me. I wanted to do this with the camera.

“I had begun to use the camera long before this in a socially conscious way. And so I began to explore working-class Afrikaner life in our district. I drove out to the kleinhoewes around the town. I would stop and ask people if I might do some portraits of them or spend time with them while they went about whatever they were doing. In this way I became intimate with some of the qualities of everyday Afrikaner life in these places, and with some of its deeply embedded contradictions.

“An old man sits for me. A black child comes and stands next to him, looking at me with curiosity. The man turns and says to the child, ‘Ja, wat maak jy hier, jou swart vuilgoed?‘ (Yes, what are you doing here, you black rubbish?), the insult meant and yet said with affection. How is this possible? I don’t know. But the contradiction was eloquent of much that I found in the relationship between rural and working-class Afrikaners and blacks: an often comfortable, affectionate, even physical intimacy seldom seen in the ‘liberal’ circles in which I moved, and yet, simultaneously, a deep contempt and fear of blacks. …

“Travelling through vast, sparsely populated parts of the country with my camera became a major part of my life at that time. I think that our landscape is an essential ingredient in any attempt at understanding not just the Afrikaner but all of us here. We have shaped the land and the land has shaped us. Often the land was unforgivingly harsh. Yet, the harsher the landscape the stronger the Afrikaners’ sense of belonging seemed to be. Many of the people whom I met in the course of those trips had a rootedness in the land of which I was very envious. Envious in the sense that I couldn’t claim 300 years of ancestry in this country. Yet, increasingly, I felt viscerally bonded to it.”

The Groote Kerk

Dr. van der Merwe, moderator of the Dutch Reformed Church, poses in the splendidly carved pulpit of the Groote Kerk in Cape Town.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories