Arts & Culture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

A Prize for the General

France’s Top Military-Literary Prize Awarded to François Lecointre

IT SHOULD surprise no-one that the French Army awards an annual prize for military literature. Since 1995, the Prix littéraire de l’Armée de terre – Erwan Bergot is awarded every year for “a contemporary work of French literature that demonstrates active commitment, of a true culture of audacity in service to the collective whole” and is named in memory of the paratrooper officer, writer, and journalist Erwan Bergot (1930-1993).

This year’s prize has been awarded to Gen. François Lecointre, the former Chief of the Defence Staff who now serves as the Chancellor of the Légion d’honneur.

This year’s prize has been awarded to Gen. François Lecointre, the former Chief of the Defence Staff who now serves as the Chancellor of the Légion d’honneur.

A graduate of Saint-Cyr, Lecointre’s book Entre Guerres (Between Wars) relays his long service to France in the land forces, including operations in Central Africa, Rwanda, Bosnia, the First Gulf War, and elsewhere.

As a young captain in Bosnia, Lecointre was concerned when his company lost radio contact with the French UNPROFOR observation post on Vrbana bridge early on the morning of 27 May 1995. When he went himself to investigate, Captain Lecointre discovered that Bosnian Serb soldiers in captured French uniforms had seized the post and taken French soldiers hostage.

Lecointre immediately informed Paris, where President Jacques Chirac circumvented the UN chain of command in Bosnia by allowing soldiers under Lecointre’s command to retake the post on the northern end of the bridge with a bayonet charge that overran the Serb-held bunker. Vrbana bridge is believed to have been the last bayonet charge of any French military operation to date.

General Pierre Schill, Chief of the Army Staff, awarded his comrade-in-arms the Prix Erwan Burgot this weekend. The prize includes a monetary award of €3,000 which Gen. Lecointre has donated to the association Terre Fraternité that provides support to France’s wounded soldiers and their families.

Entre Guerres had already won the Prix Jacques-de-Fouchier awarded by the Académie française earlier this year. (Above: Gen. Lecointre with the académicien, lawyer, and writer François Sureau.)

The Erwan Burgot prize’s jury was chaired by Gen. Schill and included the son and widow of Erwarn Burgot, alongside Col. Loïc de Kermabon, Col. Noê-Noël Uchida, the journalist and writer Guillemette de Sairigné, literary figure Laurence Viénot, Général de Division Jean Maurin, Général de Brigade Gilles Haberey, prix Goncourt winning novelist Andreï Makine, writer Christine Clerc, former head army medic Dr Nicolas Zeller, journalist Jean-René Van Der Plaetsen, Professor Arnaud Teyssier, and the historian François Broche.

Articles of Note: 17 September 2024

31½ in. x 59 in.; (link)

The Lebanese banker, writer, journalist, and politician Michel Chiha postulated that Beirut was “the axis of a three-pronged propeller: Africa, Asia and Europe”.

The city’s current airport was inaugurated in 1954, towards the height of its golden years.

In L’Orient-Le Jour, Lyana Alameddine and Soulayma Mardam-Bey report on how Beirut Airport’s story reflects the highs and lows of Lebanon’s history. (Aussi en français.)

■ Another one bites the dust: this time it’s London’s Evening Standard — traditionally the most London of London’s daily newspapers — which recently announced it will move to a single weekly printed edition.

In its heyday there were several editions per day, with “West End Final” on rare occasions topped up by a “News Extra” edition.

Stuart Kuttner, a veteran of the Standard, wrote a beautiful paean to the paper published in the Press Gazette.

■ Samuel Rubinstein shows how historians’ war of words over the legacy of the British Empire tells us more about the moral battles of today than shedding actual light on the past.

■ Wessie du Toit explores the curious columnar classicism persistent across the full spectrum of South African architecture.

■ With union presidents speaking at America’s Republic party convention, Senator Josh Hawley explores the promise of pro-labour conservatism.

■ Also at the increasingly indispensible Compact, Pablo Touzon explores how the Argentine left created Javier Milei.

■ Closer to home, Guy Dampier argues that Britain’s public services, housing, and infrastructure have reached their migration breaking point and the new Government has zero solutions.

■ Meanwhile, five hundred academics have signed a joint letter urging the Labour government not to scrap university free speech laws as the Education Secretary announced they will do.

11½ in. x 16½ in.; (link)

Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Old Kinderhook is most famous for being the birthplace of the “Red Fox”, Martin van Buren — sometime inhabitant of London and later President of the United States.

He remains the only President who was not a native English speaker, and he spoke with a thick Dutch accent until the end of his days.

If legend is to be believed (and no evidence has been presented compelling us to do otherwise) the town is also the origin of the word “okay” or “O.K.” — for the “Old Kinderhook” clubs that sprung up to support van Buren’s bid for the White House.

Like many towns up and down the Hudson valley, Kinderhook had its own newspaper — originally named the Kinderhook Herald but which later took up the idiosyncratic name of Rough Notes.

As befits the newspaper of record of an old Dutch settlement, its banner bore the motto Een=dracht maakt macht, a Dutch translation of the old Latin motto of the Seven Provinces that means “Unity makes strength”.

These old and highly localised newspapers were once the chief source of information for people in the surrounding districts and one is pleasantly delighted by the sheer variety of the contents.

In addition to news, agricultural reports, poetry, and the moral and religious column there are reports of the meetings of Congress in Washington and the legislature in Albany, trials for murder, amusing notices from other newspapers in the New World, and news of battles and great events worldwide.

Thanks to the excellent New York State Historic Newspapers online archive you can virtually flip through the pages of this and numerous other periodicals.

America’s Yacht Ensign

A Seaborne Symbol of Summer

For those of us who had the pleasure of growing up on America’s Eastern Seaboard, there are few icons more emblematic of summer than the United States Yacht Ensign snapping from the back of a sailboat.

An ensign is a maritime flag flown from vessels to show its country of registration. It is always flown from the stern of the vessel, whereas the flag that flies from the bow is called a jack. Naval ensigns are the most common but, depending on which country you’re in, there are also state or government ensigns, civil ensigns for merchant or pleasure vessels, and more.

Given Britain’s long (now somewhat faded) command of the seas, the Royal Navy’s White Ensign and the “Red Duster” of her merchant ships are the most famous ensigns of all.

During the nineteenth century, the United States government had no income tax and collected most of its still very significant revenues from customs duties, tariffs, and import charges. The Treasury Department’s revenue cutters patrolled up and down the Atlantic coast, enforcing duties and boarding vessels to inspect and collect them.

This posed a problem for the increasing fleet of pleasure craft that leisurely sailed the waters of New England, the Chesapeake, and the numerous points in between. There was no way for officials to differentiate between merchant vessels flying the American flag as their ensign and ordinary yachtsmen.

John Cox Stevens, Commodore of the New York Yacht Club, wrote to the Treasury Secretary proposing that private vessels not engaged in trade be exempt from the revenue cutters’ inspections and from clearing customs when entering or departing from American ports. Keen to lighten the load on their own inspectors, the Treasury agreed.

To signify this exemption, the United States yacht ensign was introduced in 1848: a modified form of the original thirteen-stripe, thirteen-star “Betsy Ross” flag with the addition of a somewhat jaunty anchor inside the circle of stars.

As a yacht ensign, it is flown from American private vessels only within home waters: When U.S.-registered boats are sailing abroad they should fly the ordinary fifty-star United States flag as their ensign.

It is not, however, mandatory, so American yachts can fly the ordinary flag as their ensign if they wish. The Revenue Cutters were merged with the United States Life-Saving Service in 1915 to form the Coast Guard — which has its own distinct ensign — so the threat of being raided by Treasurymen is much reduced.

Today the U.S. yacht ensign has become a symbol of American summer as far south as Key West and as up north as Bar Harbor. If you’re feeling yachty, you can even get it on a sweater. (more…)

French Railways House

A disappearing remnant of 1960s Gaullist optimism in London

While elegant proportions and a certain timeless yet modern style might sound like some bavard’s evocation of a French woman, it seems most appropriate when describing French Railways House.

180 Piccadilly was designed by the architects Shaw & Lloyd to house the main London office of the SNCF, France’s state railway, and incorporated their sales desks and information bureau for tourists on the ground floor.

With interiors by Charlotte Perriand (left) and signage lettered by Ernő Goldfinger (right) — the architect so despised by Ian Fleming that he named a Bond villain after him — the excellent proportions of this little modernist gem exude the optimistic confidence of the Gaullist Fifth Republic.

Telephone Kiosk No. 2

This must surely be the most beautiful and easily recognisable example of street furniture in the history of the world.

Scott wanted them painted a silvery hue, with a greeney-blue interior.

Instead, the Post Office, which had taken over the public telephone network in 1912, decided to paint them in its regal red livery.

I think they made the right decision.

This one can be found in Trinity Church Square, Southwark.

Bicycle Rack

We are so used to the functional ugliness of practical things in everyday life that people have forgotten we used to design useful things to be beautiful as well.

A look at the street furniture — lampposts, advertising pillars, pissoirs — of 1900s Paris and that which it inspired from Bucharest to Buenos Aires can provide a useful reminder.

Happily there are architects and designers who haven’t given up on the public realm. A fine example is this bike rack designed by B&L Architects of Charleston, South Carolina.

Charleston is probably the prettiest town in all America and the city elders have worked long and hard to protect that which makes it beautiful — not without challenges. (Watch Andres Duany on Charleston.)

I don’t know if B&L’s bike rack is going to be deployed more broadly in the city, but it looks gorgeous placed here beside the County Courthouse designed in 1790 by James Hoban.

As always, it is not turning the clock back: it is choosing a better future.

Burns Tower

Which is the oldest university in California? The Jesuits began teaching at the University of Santa Clara in 1851. In the same year, and in the same town, a gaggle of Presbyterians received a state charter to found a college that only began teaching the following year.

The Jesuits decided to crack on and start instruction before they could raise the $20,000 endowment the state required before a charter was granted whereas the Wesleyans went the other way round. That latter institution eventually moved to Stockton, east of San Francisco, where it is today known as the University of the Pacific.

When a university actually began operating seems a more appropriate foundation date than mere form filling, so despite its 1855 charter I’d say Santa Clara still beats the 1851 University of the Pacific.

Since that time, Pacific has claimed a few honours. It has educated students as wide-ranging as Jamie Lee Curtis, who left after a term to become an actress, to the orthodontist Arif Alvi who was President of Pakistan until last month. Jazz giant Dave Brubeck studied veterinary medicine here.

The campus’s Ivy League look with a California location has led to it appearing in many films, including ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’.

In the late 1950s, the elders of Pacific were looking for a way to cut the university’s water bill. They decided building a 150,000-gallon water tower was the solution. But they didn’t want to blight their beautiful campus with an unsightly functional design.

They turned to architects Howard G. Bissell and Glen H. Mortensen who created the tower that has become an icon of the university and was the tallest building in Stockton for decades.

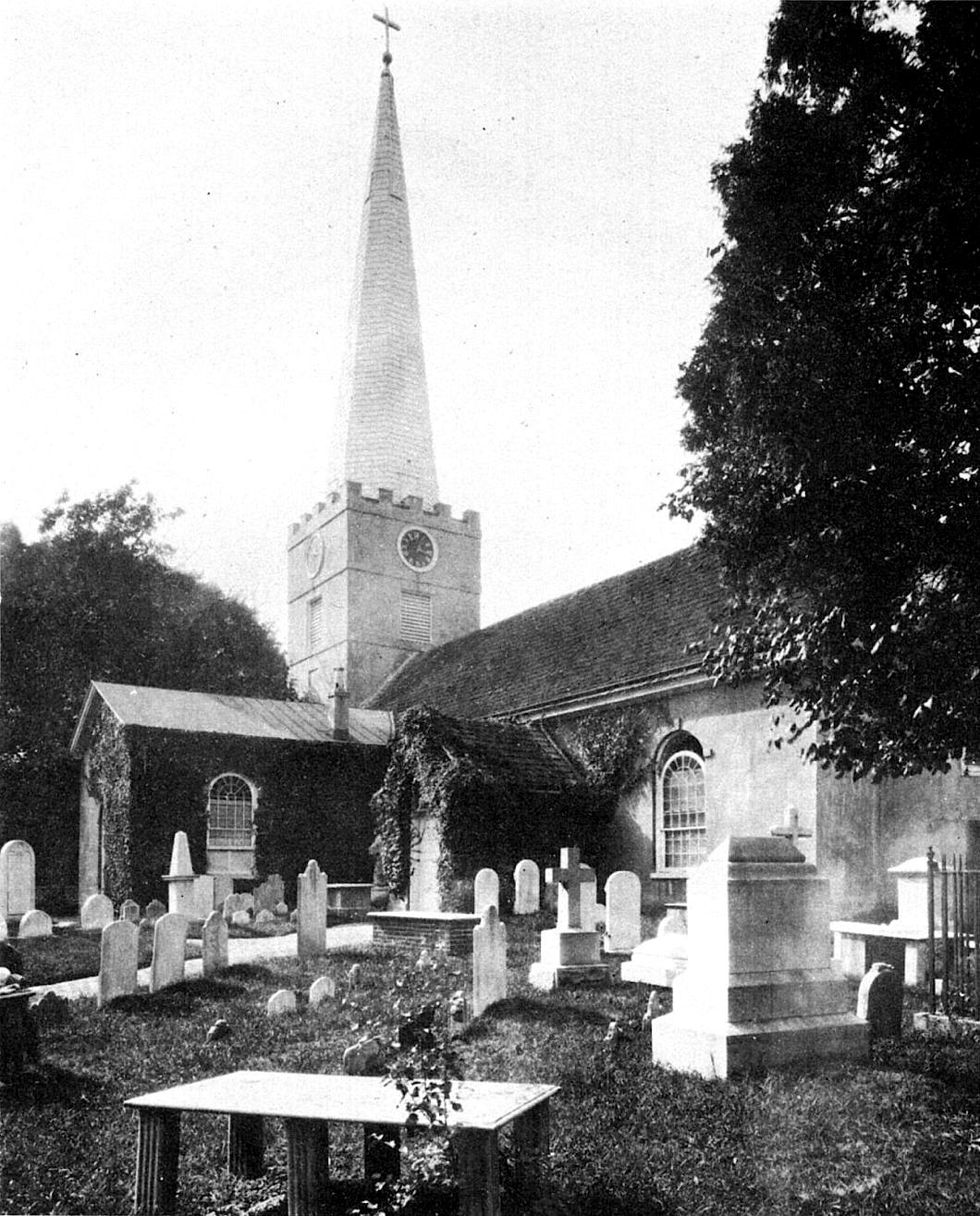

Patrick in Parliament

The Mosaic of Saint Patrick in the Palace of Westminster

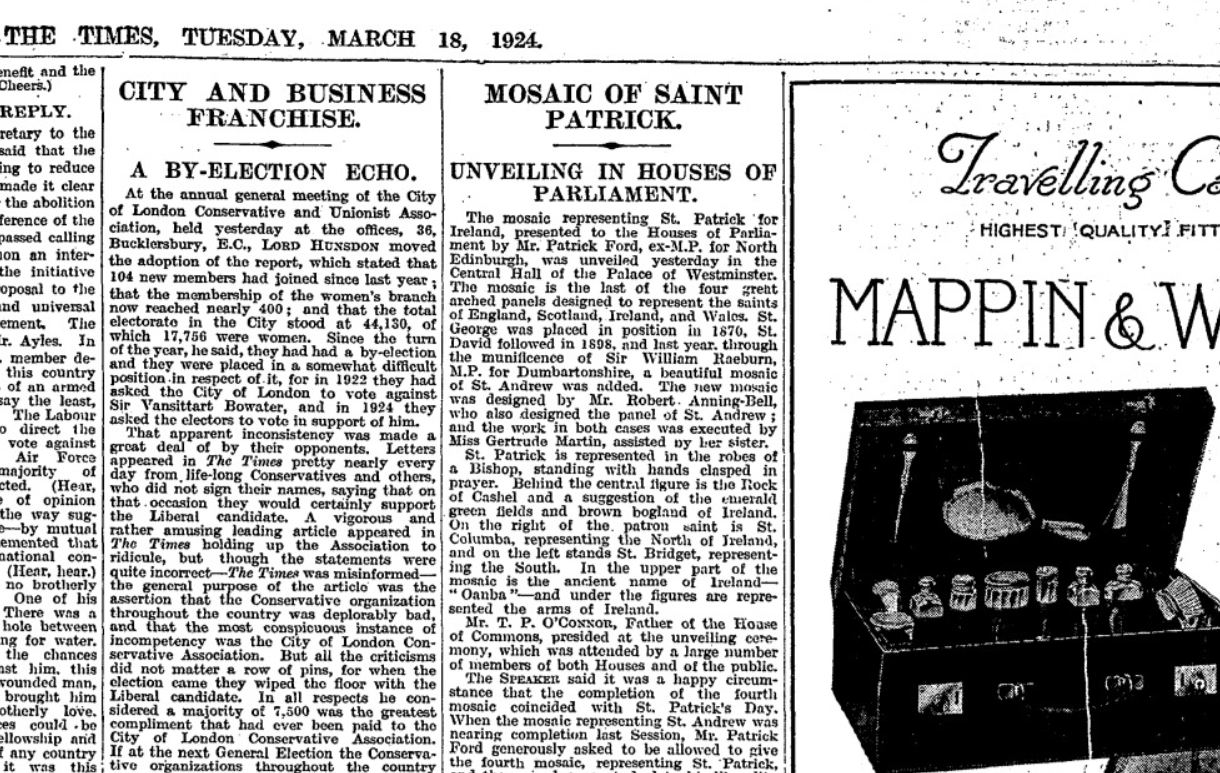

This feast of St Patrick marks the hundredth anniversary of the mosaic of Saint Patrick in the Central Lobby of the Houses of Parliament. At the heart of the Palace of Westminster, four great arches include mosaic representations of the patron saints of the home nations: George, David, Andrew, and Patrick.

The joke offered about these saints and their positioning is that St George stands over the entrance to the House of Lords, because the English all think they’re lords. St David guards the route to the House of Commons because, according to the Welsh, that is the house of great oratory and the Welsh are great orators. (The English, snobbishly, claim St David is there because the Welsh are all common.) St Andrew wisely guards the way to the bar (a place where many Scots are found), while St Patrick stands atop the exit, since most of Ireland has left the Union.

The mosaic of Saint Patrick came about thanks to the munificence of Patrick Ford, the sometime Edinburgh MP, in honour of his name-saint. Saint George had been completed in 1870 with Saint David following in 1898.

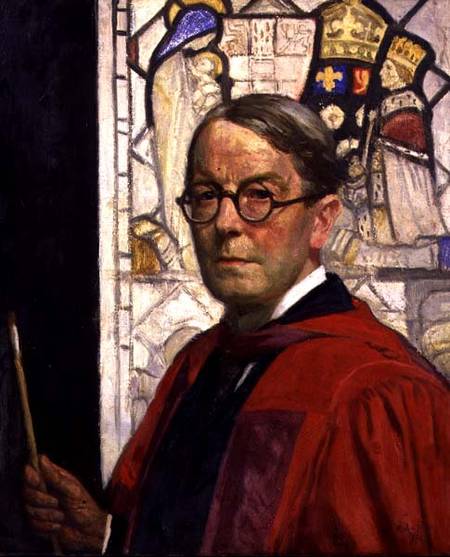

Sir William Raeburn MP commissioned the artist Robert Anning Bell (depicted right) to design the mosaic of Saint Andrew in 1922, which so impressed Patrick Ford that he decided to commission the same artist to depict the patron saint of Ireland.

Sir William Raeburn MP commissioned the artist Robert Anning Bell (depicted right) to design the mosaic of Saint Andrew in 1922, which so impressed Patrick Ford that he decided to commission the same artist to depict the patron saint of Ireland.

Anning Bell had earlier completed the mosaic on the tympanum of Westminster Cathedral from a sketch by the architect J.F. Bentley. Following his work in Central Lobby he also did a mosaic of Saint Stephen, King Stephen, and Saint Edward the Confessor in Saint Stephen’s Hall — the former House of Commons chamber.

In the mosaic, Saint Patrick is flanked by saints Columba and Brigid, with the Rock of Cashel behind him. As by this point Ireland had been partitioned, heraldic devices representing both Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State are present.

On St Patrick’s Day in 1924, the honour of the unveiling went to the Father of the House of Commons, who happened to be the great Irish nationalist politician T.P. O’Connor, then representing the English constituency of Liverpool Scotland (the only seat in Great Britain ever held by an Irish nationalist MP).

“That day,” The Times reported T.P.’s words at the unveiling, “in quite a thousand cities in the English-speaking world, Saint Patrick’s name and fame were being celebrated by gatherings of Irishmen and Irishwomen. Certainly he was the greatest unifying force in Ireland.”

“All questions of great rival nationalities were forgotten in that ceremony. From that sacred spot, the centre of the British Empire, there went forth a message of reconciliation and of peace between all parts of the great Commonwealth — none higher than the other, all coequal, and all, he hoped, to be joined in the bonds of common weal and common loyalty.”

T.P.’s remarks were greeting with cheers.

The Most Honourable the Marquess of Lincolnshire, Lord Great Chamberlain, accepted the ornamental addition to the royal palace of Westminster on behalf of His Majesty the King.

Articles of Note: 13 March 2024

My then-flatmate was getting married the next day and much pottering-about sorting things was required but the idiosyncratic beauty of this building captured my imagination — part Norman, part Moorish. I was almost insulted that I hadn’t come across it in any of my bookish explorations.

The historian Edmund Harris covers Chideock in his lusciously illustrated post on Recusancy in Dorset and the ‘other tradition’ of Catholic church-building.

■ Generations ago it was said that the three institutions no British politician dared offend were the trade unions, the Catholic Church, and the Brigade of Guards. In 2020s Britain there is only one caste which must always be obeyed: the ageing, moneyed homeowners.

Not only do these “NIMBYs” (“Not In My Back Yard”) jealously guard their freeholds, they do whatever they can to prevent more houses being built to guard the value of their prize possessions, vastly inflated by a combination of lacklustre housebuilding and irresponsible leap in migration. As old people vote and young people don’t — and when they do, vote badly — few sensible people can find a way out of this quagmire.

It might be worth looking to the Mediterranean, where Tal Alster tells us How Israel turned urban homeowners into YIMBYs.

■ It’s disappointingly rare to see intelligent outsiders give a considered impression of the current state of play in the Netherlands — that’s Mother Holland for us New Yorkers. Too often commentators in English are either rash cheerleaders for the hard right or bien-pensant liberals eager to castigate and chastise. Both rush to judgement.

What a rare diversion then to read Christopher Caldwell — the only thinking neo-con? — attempt to explore and explain the success of Geert Wilders in the recent Dutch elections.

■ One in ten of Lusitania’s inhabitants are now immigrants, and this discounts those — many from Brazil and other former parts of the once-world-spanning Portuguese empire — who have managed to acquire citizenship through various routes.

Ukrainian number-plates are now frequently be seen on the roads of Lisbon, as far in Europe as you can get from Big Bad Uncle Vlad.

Vasco Queirós asks: Who is Portugal for?

■ Speaking of world-spanning empires, in true andrewcusackdotcom fashion, we haven’t had enough of the Dutch — but we have had enough of their wicked wayward heresies.

Historian Charles H. Parker explores the legacies of Calvinism in the Dutch empire.

■ The City of New York itself is the best journalism school there is. Jimmy Breslin dropped out of LIU after two years, eventually taking up his pen. Pete Hamill left school at fifteen, apprenticed as a sheet metal worker, and joined the navy.

William Deresiewicz argues that a dose of working-class realism can save journalism from groupthink.

■ The New Yorker tells us how a Manchester barkeep found and saved a lost (ostensible) masterpiece of interwar British literature.

■ Our inestimable friend Dr Harshan Kumarasingham explores David Torrance’s history of the first Labour government on its hundredth anniversary.

■ And finally, one for nous les normandes (ok, ok, celto-normandes): Canada’s National Treasure David Warren briefly muses that the Norman infusion greatly refined Anglo-Saxon to give us the superior English tongue we speak today.

Cambridge

There’s a Dutch vibe to Cambridge that I rather like — but also a lingering Protestant Cromwellianism that I don’t. These two factors are not unconnected, and the highway that once was the North Sea is not so far away.

It is not a bad town. It’s like they took Oxford apart, put it back together again in not quite the same way, and added a lot of Regency infill. Oxford is more mediaeval, Georgian, and neo-mediaeval, whereas Cambridge is mediaeval, Tudor, and Regency.

The Cam is slower, quieter, and more peaceful than the Isis, which again gives it the quality of a Hollandic canal. I suspect the punting is better — or at least easier — here than at Oxford.

And of course it is rather more spacious than Oxford, which is hemmed in by geography in a way that Cambridge isn’t.

But it is also eerily quieter. A smart restaurant on a Thursday night was dead by half ten, and the staff refused our plaintive request for a second round of Tokay. (Protestantism.)

Immanuel on the Green

The prettiest situated church in the little state of Delaware

In the old Delaware hundred of New Castle on the town green sits the Immanuel Protestant Episcopal Church — the first Church of England parish in what is now the State of Delaware. This part of the world started out as New Sweden, but our Dutch forefathers of old, settled as they were in New Amsterdam, quickly took umbrage at the Scandinavian presence in what they viewed as a distinctly Netherlandic domain.

By the time Sweden and Poland went to war in 1755 — a conflict, confusingly, called the Second Northern War by some and the First Northern War by others — a Polish citizen of New Amsterdam had convinced the governor, Peter Stuyvesant, to let him take a team to go and establish a Dutch fort in the lands claimed by the Swedes. Stuyvesant named the settlement Fort Casimir after the many legendary Polish kings to bear that name, as well as the reigning King of Poland at the time, John II Casimir.

The dastardly Swedes captured Fort Casimir in 1654, led by an Östergötlander by the name of Johan Risingh. (As it happens, Rising had studied at Leiden in the Netherlands in addition to his native land’s university of Uppsala.) The Swedes had seized the fortress on Trinity Sunday, and so they rechristened it as Fort Trinity — or Fort Trefaldighet in their own tongue.

Stuyvesant was forced to lead an expedition himself to kick the Swedes out and, after a scrap that went down as “the Most Horrible Battle Ever Recorded in Poetry or Prose”, he returned to Dutch Manhattan in triumph.

“It was a pleasant and goodly sight to witness the joy of the people of New Amsterdam at beholding their warriors once more return from this war in the wilderness,” no less a source than Diedrich Knickerbocker recounts.

The schoolmasters throughout the town gave holiday to their little urchins who followed in droves after the drums, with paper caps on their heads and sticks in their breeches, thus taking the first lesson in the art of war. As to the sturdy rabble, they thronged at the heels of Peter Stuyvesant wherever he went, waving their greasy hats in the air, and shouting, ‘Hardkoppig Piet forever!’

It was indeed a day of roaring rout and jubilee. A huge dinner was prepared at the stadthouse in honor of the conquerors, where were assembled, in one glorious constellation, the great and little luminaries of New Amsterdam. … Loads of fish, flesh, and fowl were devoured, oceans of liquor drunk, thousands of pipes smoked, and many a dull joke honored with much obstreperous fat-sided laughter.

But the joyous dominion the Hollanders held over the former Swedish territory was to be short-lived. By fate and the divine hand, the Duke of York — later our much beloved and since departed majesty King James II — seized New Amsterdam without firing a shot in 1664 and New Netherland became the Province of New York overnight.

Down on the banks of the Delaware, the Dutch-founded Fort Casimir, re-consecrated as Fort Trinity by the Swedes, had returned to Dutch control under the name of Nieuw Amstel. The English now named it New Castle, a name which has stuck ever since.

By a livery of seisin, the Duke of York transferred this part of his fiefdom to William Penn in 1680, who went and founded Pennsylvania a year later. But the English, Dutch, and Swedish inhabitants of “the lower counties on the Delaware” bristled under the dominance of the culturally distinct Quakers. They petitioned the Crown to be governed by a separate legislature, which privilege was duly granted in 1702.

A Happy Home in Maida Vale

Her ‘Nurse Matilda’ series of children’s books was illustrated by her cousin, Edward Ardizzone RA, and was later adapted for the silver screen as the Nanny McPhee films starring Emma Thompson.

Brand and her husband lived in this rather happy looking home in leafy Maida Vale which has now come up for sale.

Built in 1822 (and Grade II-listed), the house was also deployed as a setting by the author — sometime chair of the Crime Writers’ Association — in her book London Particular.

As Brand described the story:

It is set in a London house and everybody is either a member or close friend of the family – it is a doctor’s house, a Regency house in Maida Vale; in fact, it is my own house with all my own family and animals and things in it just for fun.

Maida Vale has also been the setting for mysteries written by PD James and Ruth Rendell — and of course the ‘M’ in Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘Dial M for Murder’ stand for Maida Vale itself.

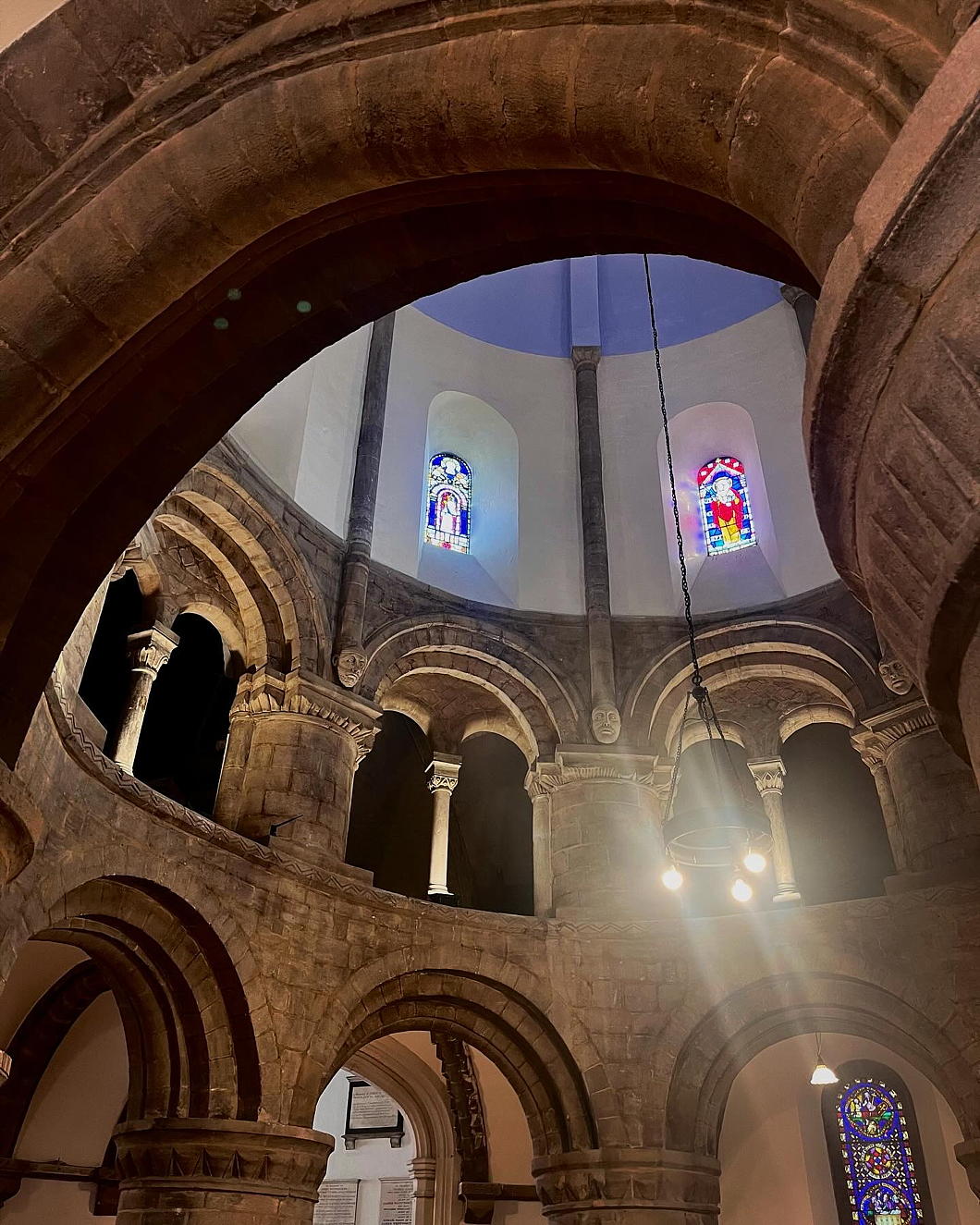

St Mary Overie in Lent

Here in Southwark I nipped in to Evensong in the late twilight of a winter’s day. They do it very beautifully with a full choir at the Protestant cathedral — old Southwark Priory or St Mary Overie to us Catholics, St Saviour’s to our separated brethren.

As it is the penitential season, the Lenten Array is up at Southwark Cathedral, theirs apparently designed by Sir Ninian Comper.

What is a Lenten Array? Sed Angli writes on the Lenten Array in general while Dr Allan Barton has written on Southwark Cathedral’s Lenten Array specifically.

And of course our friend the Rev Fr John Osman has one of the most beautiful Lenten Arrays at his extraordinary Catholic parish of St Birinus — a stunning church previously mentioned.

(The photograph of our local array is from Fr Lawrence Lew O.P.)

ICAA Videos on Architecture

The Institute of Classical Architecture and Art is one of the absolute gems of American civic society.

As part of their remit of promoting traditional architecture and its many associated arts they have a good many videos on their website covering numerous subjects and in a variety of depths and lengths of time.

Here are just a handful.

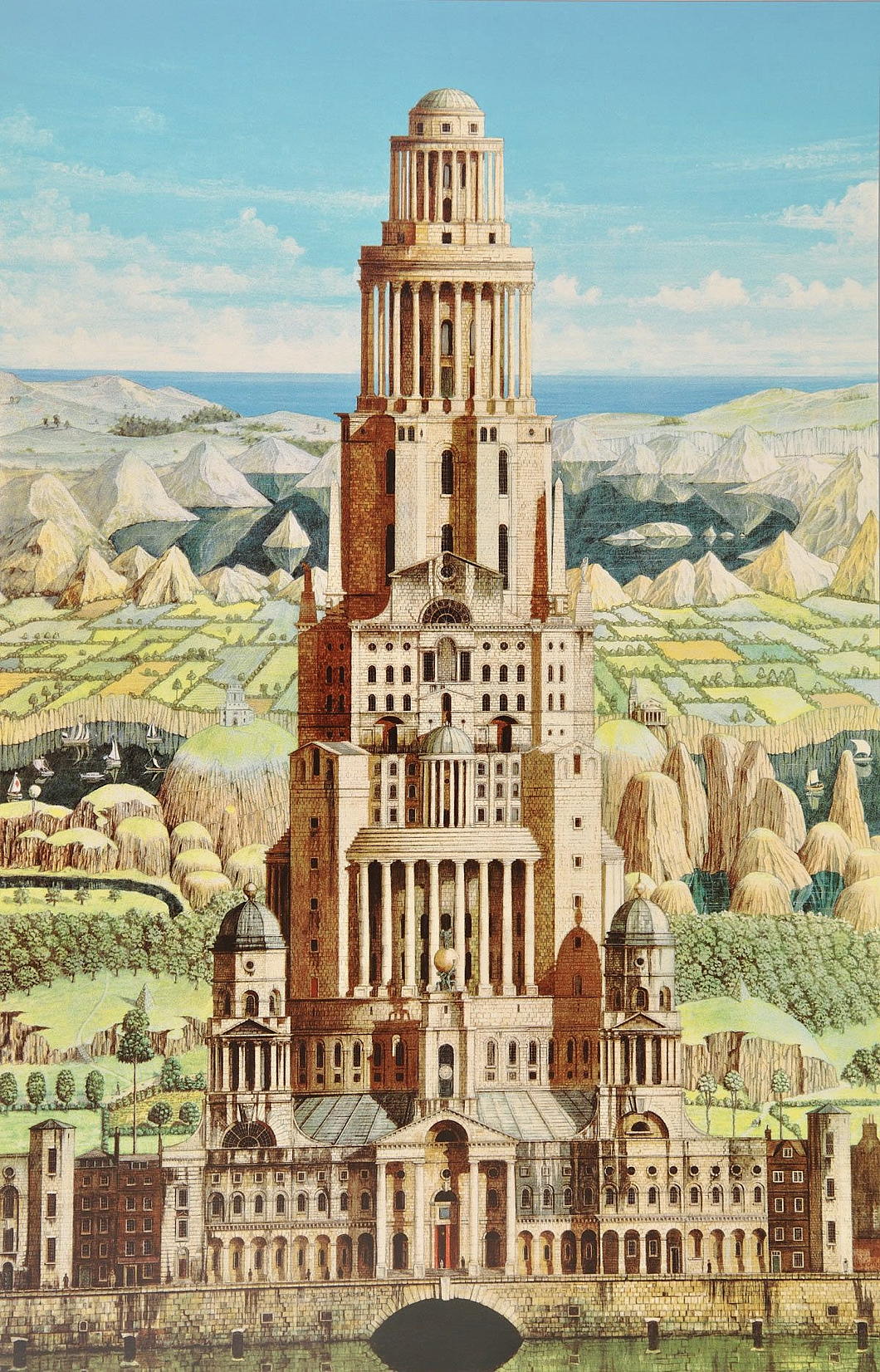

Hawksmoor’s Dream

27½ in. x 17¾ in.; 1987-1991

Andrew Ingamells is an excellent draughtsman who is probably the finest architectural artist in Britain today.

His depictions of Westminster Cathedral and the Brompton Oratory (amongst others) are in the Parliamentary Art Collection, and he has done Loggan-style portrayals of the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge as well as three of the four Inns of Court in London.

The above capriccio is a wonderful treat. I think someone should build it.

Canterbury Gate

10 in. x 16¼ in., 1799; Tate Collection

Turner’s painting captures Christ Church’s Canterbury Gate from Oriel Square. (As it happens, this is Canterbury Gate at Christ Church in Oxford and, conversely, there is a Christ Church Gate at Canterbury in Kent.)

Given the greenery of the vegetation, this is almost certainly not the work that inspired Betjeman to write his winter poem ‘On an Old-Fashioned Water-Colour of Oxford’:

A winter sunset on wet cobbles, where

By Canterbury Gate the fishtails flare.

Someone in Corpus reading for a first

Pulls down red blinds and flounders on, immers’d

In Hegel, heedless of the yellow glare

On porch and pinnacle and window square,

The brown stone crumbling where the skin has burst.

A late, last luncheon staggers out of Peck

And hires a hansom: from half-flooded grass

Returning athletes bark at what they see.

But we will mount the horse-tram’s upper deck

And wave salute to Buols’, as we pass

Bound for the Banbury Road in time for tea.

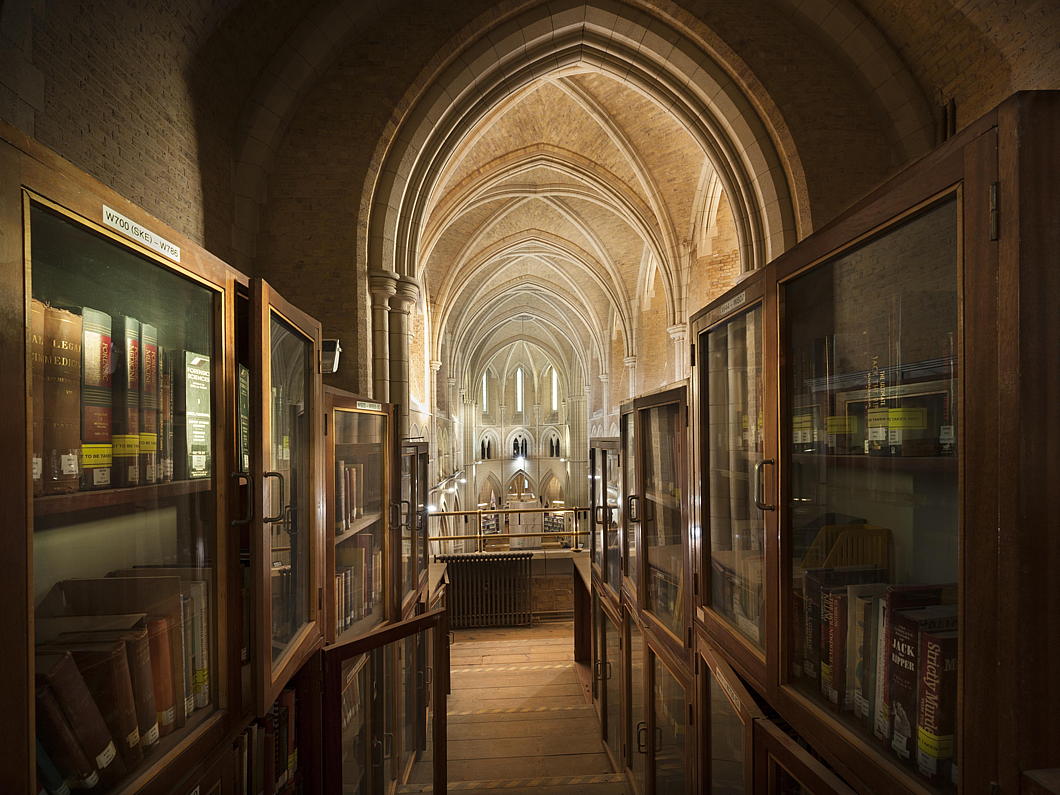

Whitechapel Library

There are precious few suitable uses for former church buildings.

At the worst end of the spectrum is nightclub, though bar or restaurant often doesn’t fall terribly far behind either. To my mind, I can hardly think of a more suitable use for an elegant and beautiful former church than to be turned into a library.

An example: the former Anglican parish church of St Philip, Stepney, in Whitechapel. Designed by Arthur Cawston, of whom I know little, it reminds me of J.L. Pearson’s Little Venice church for the eccentric “Catholic Apostolic Church”.

St Philip’s was declared redundant in 1979, at which time the neighbouring London Hospital still had its own medical school. This has since merged with that of St Bartholomew’s into “Barts and the London” or “Barts” or “BL”, under the auspices of Queen Mary University of London.

As St Philip’s sat pretty much smack dab in the middle of the campus of the London Hospital (augmented to the Royal London Hospital from 1990) and the college was surviving in cramped accommodation, it was decided to restore the fabric of the church and convert it to a library and study centre. The crypt of the church was adapted to house computer, teaching, and storage rooms as well as the museum of the Royal London Hospital.

Rather than preserve it in aspic, the medical school decided to keep this as a living building by commissioning eight new stained-glass windows to replace plain glass. They are completed along rather forthright German modernist designs and are dedicated to such themes as Gastroenterology and Molecular Biology. They will not be to everyone’s taste, but it is admirable for a medical school to commission stained glass windows at the turn of the millennium.

The Survey of London’s Whitechapel Project has a typically thorough entry on QMUL’s Whitechapel Library / the former church, including these applaudable photographs the Survey commissioned from Derek Kendall.

Architectural Exhibitions

The Architecture Association is renowned as the most pedantic of training schools for the profession. Housed as it is in an immaculate set of Georgian townhouses in Bedford Square, its students are rigorously trained to avoid anything that might be beautiful, expressive of the inherited tradition of millennia, or pleasing to the human condition.

Nonetheless, I love architectural models, and the AA is having an exhibition of a handful of models of the various places in which the Warburg Institute has been housed across its peripatetic and tumultuous history until it found its thus-far permanent home in Woburn Square in Bloomsbury.

“Architecture and interiors were crucial for Aby Warburg’s interrogation of culture,” the AA opaquely tells us.

“Between 1923 and 1958, designs were commissioned for buildings, interiors, and exhibitions, as the Warburg Library and Institute moved through a series of homes, first in Hamburg and then in London,” they more helpfully inform.

“This exhibition, an itinerant archive of models and drawings that portray the seven different spaces the Warburg Institute has occupied, sheds new light on Warburg’s involvement with architecture.”

19 January 2024 to 7 March 2024

Mon-Sat, 11h00-19h00

Gallery, Architectural Association (free)

Connectedly, the University of London is hosting an exhibition looking at Charles Holden’s masterplan for that institution’s Bloomsbury campus.

This show “celebrates the architect’s vision of what a modern university could be through displays of detailed architectural models, archival documents, photo albums, and other mixed media”.

Senate House is an amazing building but I think we can be glad the full scale of its original plan — stretching all the way up towards Gordon Square — was never completed.

17 Jan 2024 to 17 March 2024

Mon-Fri, 09h00-17h00

Senate House, University of London (free)

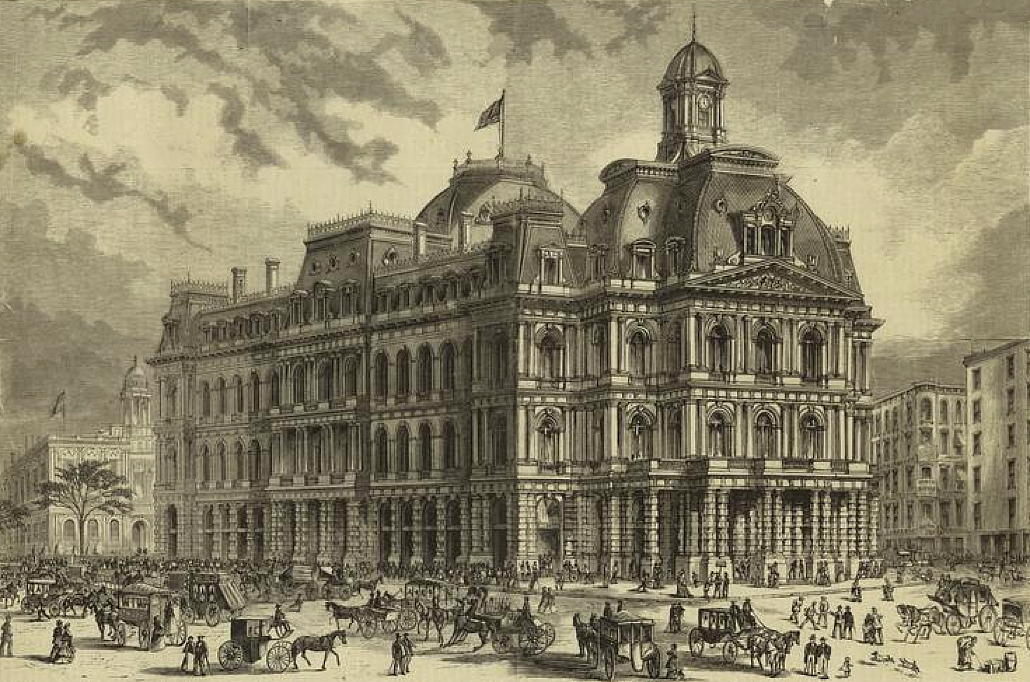

City Hall Post Office

New York’s Lost Second Empire Gem

The Second Empire as an architectural style in America has always bad rap. The most prominent example in the New World is the Old Executive Office Building next to the White House in Washington, D.C. — formerly known as the State, War, and Navy Building after the three government departments it housed in the days of a slimmer federal state.

The OEOB was designed by Alfred B. Mullett, a Somerset-born architect who had immigrated to the United States when he was eight years old. Mullett trained as an apprentice under Isaiah Rogers who was Supervising Architect of the U.S. Treasury Department. In practice, the Treasury’s architect designed all the American federal government’s office buildings across the Union, and Mullett inherited the job in 1866.

At that time, the ever-expanding city of New York was desperately in need of a new post office, having occupied the former Middle Dutch Church since 1844. Congress approved funds for a new building, and an architectural competition attracted fifty-two entries. Instead of choosing one of the entries, five leading contenders were selected to collaborate on producing a single design.

Mullett criticised the joint design as too expensive and called in the job to his own office so that he could design the building himself.

Mullett’s Second-Empire design provided for a post office open to the public on the ground floor, mail sorting rooms below it, and space for federal courtrooms as well as offices for federal agencies in the floors above the postal facilities.

The original design (above) called for only four storeys but during the design process the need for more space to serve the growing city moved Mullett to slip another floor in beneath the mansard roof. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories