Arts & Culture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Winchester Mansions

STARING ACROSS Sea Point Promenade towards the waters of the Atlantic in Cape Town, there sits Winchester Mansions. The hotel was built in 1922 in a style emblematic of the period’s revival of interest in the Dutch colonial age at the Cape. People often associate the 1920s with Art Deco, but the style was only just emerging in Paris at the time, and wasn’t even called ‘Art Deco’ until the 1960s. The ‘mother city’ has its fair share of Art-Deco and Moderne buildings, but architectural trends took a while to arrive in South Africa — though they tended to last longer then elsewhere. The Cape Dutch Revival emerged in the 1890s and perhaps reached its high-water mark in the 1900s and 1910s. Curiously, it is not associated with the simultaneous emergence of Afrikaans as a language and the rising consciousness of Afrikaner identity, but rather with a very Anglo and colonialist mindset. It was Dorothea Fairbridge and Milner’s ‘Kindergarten’ — respectively the social and political forces seeking to unite all of South Africa under the British crown — that promoted the adoption of the Cape Dutch as a national style. Thus the years leading up to Union in 1910 and its initial decade or two were the heyday of the Cape Dutch Revival as it was the favoured boustyl for the respectable Cape- and Rand-based imperialists.

The Architecture of Immaturity

Have you ever come across the French Ministry of Culture on the Rue Saint-Honoré? It’s a perfect example of the architecture of immaturity. The government ministry was formerly strewn across nineteen different sites throughout Paris. The decision was made to consolidate their offices in one place, and the suitably central location near the Palais Royal was chosen.

The main building on the site is a handsome building from the late nineteenth-century or at the latest 1900s, with a modern 1960s office building stuck behind it. The Ministère chose architect Francis Soler to “unify” the buildings into one. At first, this was meant to be done solely through an interior reorganisation, but Soler decided to add a strange grille to the façade. (more…)

Decline of the Herr Professor

The Herr professor has been caught up in a whirlwind of protest, eventually to emerge as a humble guest on a television talk show.

No Nobel prize compensates for this loss of prestige at the apex of a crumbling pyramid.

His desperate references to the false problem of “academic freedom” sound not only hollow, but like the exchanges between pagan Roman priests at magical ceremonies in whose effectiveness they no longer believed.

Modern Age, Spring 1999

The Advent of Virgin Australia

Virgin Atlantic Airways has always inexplicably attempted a fine balance between the crisply modern and the vaguely old-school. It is also unashamedly British. When the lumbering giants at British Airways were busy banishing the Union Jack from their aircraft livery — prompting Baroness Thatcher to cover the model of a BA 747 with a handkerchief — Sir Richard Branson said “We’re British: why don’t we fly the flag?” The Union Jack was added to every Virgin Atlantic plane and a flag design was later added to the wingtips. Virgin Atlantic now has a patriotic red-head (above) bedecked in the Union flag on the nose of each of its aircraft glamourously advertising their national origins in this hyperglobalist age.

Virgin Group has not restrained itself from expanding beyond the trans-Atlantic flightpath. In 2000, they established Virgin Blue in Australia, originally flying only between Brisbane and Sydney, but gradually expanding within the country, especially after the 2001 collapse of the major domestic carrier Ansett Australia. In 2003, Virgin started Pacific Blue Airways out of New Zealand, operating trans-Tasman routes, followed by the founding of Polynesian Blue in 2005 running flights between New Zealand, Australia, and Samoa. Finally, V Australia was started operations in 2009 running long-haul flights out of Australia. (more…)

Dino Takes on Nic & Rem

Dino Marcantonio is on his usual top form when responding to an interview with the “Dutch architect and uber-gobbledegook-meister” Rem Koolhas by Nicolai Ouroussoff, the architecture praiser for the New York Times. Many modernists now find themselves in the role of perverse preservationists, trying to save ugly modernist buildings that are already falling apart because of their inherent conceptual flaws and rejection of inherited architectural wisdom. But while the Mods want to save the crumbling monstrosities, they attack the natural human instinct to preserve what is beautiful (i.e. traditional and vernacular architecture) and to destroy or get rid of what is ugly (their own work, the “ambitious” carbuncles of the past century).

Koolhaas and Ouroussoff pretend to confuse the true spirit of preservation with hoarding. A hoarder makes no value judgments about what should be kept. It all stays, and the result is his home is a dump. If we keep everything, we wind up preserving nothing–and that, my friends, is what Koolhaas is really all about. His endgame is the embalming of our architectural identity. He is suffering from an acute case of cronophobia, the irrational fear that old things might still be alive to us today.

Dino, however, is not having it:

Consider another approach taken by the Venetians toward the beautiful church Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari. Completed in the early 14th century, it has been lovingly embellished by generations and generations, all meaningfully, and without any angst about what is authentic and what is not. It has also suffered through suppression, looting, and radical restoration. I Frari has been through it all. It is almost 700 years old, yet because it has been properly cared for, it still looks fresh as a garden daisy. And it is mobbed by visitors year-round who yearn to follow its example, not only in the preservation and handing down of churches, but also our cities, our homes, our culture.

Turning the Book on its side

Books are a central obsession of mine. I’ve a reasonably large and ever-increasing library of my own and wherever I’ve called home there have been larger collections available to tap into: the Society Library in Manhattan, the Gericke-biblioteek in Stellenbosch, and the mostly excellent public libraries dotted around lower Westchester. When you see the wide range and styles of the book — it’s size, proportion, paper, appearance — it’s depressing to see how monotonous contemporary book publishing is today. I have a thousand different ideas on book publishing and the wide gaps in the market that are completely ignored today, but here’s one inventive idea I didn’t have.

According to Le Figaro, Editions Point Deux (a subsidiary of the La Martinière group, the third-largest publishers in France) has begun offering what it calls « le plus portables des livres » . These little books are printed on their side to be read like a flipbook rather than in the more conventional format. The idea, apparently, comes out of Holland and has proved successful in Spain, but I haven’t come across it at all in the English-speaking world.

The first question is: what’s the point? At 4.75 in. x 3.15 in., they’re a handy size, but is anything actually gained by turning the text on its side? I imagine it’d be helpful for commuters, but I think it’d be difficult to judge the concept without actually having one in hand and using it, so I think I’ll refrain from handing down a verdict just yet. Very boring of me, I know, but I’ll admit I’m intrigued by the idea.

Civilised Barbarism, Barbaric Civilisation

“Despite my inclinations to the contrary, I have racial sensitivities. I am Latin. I regard the civilised barbarian in the North with an inherited sense of mistrust. Today [the United States] has become a colossal society, and has adopted the goal of imposing its industry, its commerce, and its imperialism. Each citizen of the Union is a kind of stockholder… [upholding] an ideal of material perfection above moral perfection, and equating civilisation with the triumph of industry and commerce. We, by contrast, descendants of the Latins and educated by the Greeks, regard that person as most civilised who is most morally perfect. … I am proud to say I am bored with railroads and factory chimneys.” – Belisario Montero

ONE OF THE best aspects of Catholicism is the affirmation (for lack of a better word) of absolutely everything that is good throughout the world. All the peoples of the earth, each with their particular genius, eventually descend from the same parents. This gives one, I hope, a certain sympathy towards every nation and every people, and an anticipation that each one will eventually grow into the full flower of a Christian order appropriate to their particular characteristics and personality. Christianity is not oppressive and conformist in its universalism but instead all-embracing.

There is much to be admired in the sentiments expressed by Belisario Montero, an Argentine diplomat, in the comments cited above. To put them in context, they were made after the final collapse of the Spanish Empire following the Spanish-American War of 1898. Argentina, as you already know, is a place that excites me. In her is found so much of the idea of Europe, varyingly perfected and perverted, accidentally demolished in an attempt to save it and then put back together again not precisely as it was before. Marx “travelled” to Buenos Aires, but so did Maurras (and perhaps the Frenchman was more influential). For a time, photographs of Mussolini cut from the illustrated magazines were plastered onto the walls of aspirational working-class porteños trying to keep up with the latest European fad, and the military elite and social aristocracy combined to oppose the vulgar and destructive forces of liberal democracy and unbridled capitalism. Almost every coup in the nation’s history was received with a sigh of relief, especially (and ironically) the coups getting rid of whomever the previous welcome coup put in charge. Argentina has a long history of terrible success and beautiful failure. Perón himself is the very embodiment of this.

Of course, unlike Don Belisario, I am not a Latin. (more…)

Bo Bartlett

THERE IS SOMETHING vigorously American about the art of Bo Bartlett. The modern realist was born in Columbus, Georgia, and studied in Italy under the Arthur Ross Award laureate Ben Long (one of the “greatest draughtsman of the twentieth century” according to Philippe de Montebello) before moving on to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. After completing a filmmaking degree at New York University, Bartlett embarked upon a five-year process creating a film covering the life and works of Andrew Wyeth, in collaboration with the artist’s wife Betsy. The artist’s work certainly shows the influence of Wyeth, as well as other American artists like Thomas Eakins, Edward Hopper, and Winslow Homer.

Hopper’s works, I’ve always found, have a particular quality of still abandonment, as if the scenes he depicts are living but just abandoned five minutes ago. Bo Bartlett’s paintings have a similar feel: they often exude a slight air of uncertainty and disquiet. There’s the looming threat of anarchy in The End of the 20th Century, also insinuated in So Far, as well as the reversal of the grounded American flag implied in Cradle. Other paintings, like Calling and Deer are peans to the animal kingdom. Still more are disturbingly quiet odes to the American coast — Bartlett divides his time between Puget Sound on the Pacific and Maine on the Atlantic. Whether beautiful portents of doom or eery celebrations of American life, the viewer suspects that there are stories not being told, and that the artist’s paintings conceal as much as they reveal. (more…)

Branding the Rowing Nation

National Governing Bodies in Rowing and their Logos

THE OTHER DAY I was flipping through some publication and came across a photograph of two people standing in front of a boathouse. Emblazoned upon the building was the above logo, along with the words ‘British Rowing’. As a former member of SARA (the Scottish Amateur Rowing Association), I found this quite intriguing as I’d never heard of any such organisation.  Like many sports, rowing is organised on a country-wide level (i.e. England, Scotland, Wales), not on a union level (the United Kingdom). Ever wary of centralisation, I was relieved, albeit a bit confused, to discover that the group now branding itself as ‘British Rowing’ is actually the Amateur Rowing Association, the ruling body for the sport in England, not Britain. The ARA was founded in 1882, but lamentably decided to end its ban on non-amateurs in 1998. They kept the ARA name regardless until now. Having the word ‘Amateur’ in their name was obviously a bit inaccurate, but if accuracy was the aim, why have they decided to style themselves ‘British Rowing’ when they only speak for England? What’s wrong with ‘English Rowing’? Very odd, if you ask me. (more…)

Like many sports, rowing is organised on a country-wide level (i.e. England, Scotland, Wales), not on a union level (the United Kingdom). Ever wary of centralisation, I was relieved, albeit a bit confused, to discover that the group now branding itself as ‘British Rowing’ is actually the Amateur Rowing Association, the ruling body for the sport in England, not Britain. The ARA was founded in 1882, but lamentably decided to end its ban on non-amateurs in 1998. They kept the ARA name regardless until now. Having the word ‘Amateur’ in their name was obviously a bit inaccurate, but if accuracy was the aim, why have they decided to style themselves ‘British Rowing’ when they only speak for England? What’s wrong with ‘English Rowing’? Very odd, if you ask me. (more…)

A Little More Graaff-Reinet

Here’s just a handful more photos of Graaff-Reinet from the blog of Angelika Wohlrab, a South African tour guide, author, and photographer. Above is another Cape Dutch gem, the Urquhart House with its splendid plasterwork design in the gable. (more…)

Graaff-Reinet

The Gem of the Karoo

IF YOU HEAD OUT from Cape Town making for the Valley of Desolation, you take the main road to Johannesburg, breaking ranks at the town of Beaufort-West in the Great Karoo, where you head eastwards on the R61. That road eventually joins up with the N9 (famous for its “Uniondale Ghost”) and, before you reach the Valley, takes you to the pleasant little town of Graaff-Reinet. The town was founded in 1786, making it the fourth-oldest in South Africa, after Cape Town — the “mother city” — Stellenbosch, and Swellendam. Graaff-Reinet was named in deference to the Dutch governor of the day, Cornelis Jacob van de Graeff, and his wife whose maiden name was Reynet, but the burghers earned an early reputation for rebelliousness, proclaiming their own independent republic in 1795, with further uprisings in 1799 and 1801. While now situated in the Xhosa-dominated Eastern Cape, Graaff-Reinet is predominantly Afrikaans.

The town, which rests on a bend in the Sunday’s River, has a host of architectural delights, of which my favourite is the Reinet House (below). It was built in 1812 as a parsonage for the Dutch Reformed minister, and was later part of the teacher training college until it fell vacant and was restored as a museum after the Second World War, being opened in 1956 by the Rt. Hon. E.G. Jansen, the Governor-General of the day.

The Modern Baroque: Brasini in Parioli

The Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary

GOOD ARCHITECTURE requires a combination of willpower, taste, and resources. This nexus used to occur quite often; instances from the Renaissance and the long nineteenth century come most easily to mind. A late twilight of this combination is found in the magnum opus of the Italian architect Armando Brasini: the Church of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Rome’s swish Parioli neighbourhood.

The  church, a modern expression of the Baroque, has somewhat curious and disjointed origins. Every age has left its imprint on Rome in one way or another: the Rome of the Republic, the Rome of the Empire, the Rome of the Popes, the Rome of the Liberals, the Rome of the Fascists, the Rome of the Italian Republic. In the 1900s, it was realised that the Church had not made a significant contribution to the great architecture of Rome for some time. Worse: the more significant structures of the past century were mostly built by the government of the Sardinian kingdom that conquered Rome and gave itself the fanciful, if geographically correct, name of ‘Italy’. A new church was needed, on a monumental scale, to be the age’s contribution to the great churches of Rome. Originally, the church was to be dedicated to St. James the Greater, but as preparations increased for the International Marian Year of 1924, it was decided the cult of the Immaculate Heart of Mary would take precedence instead. (more…)

church, a modern expression of the Baroque, has somewhat curious and disjointed origins. Every age has left its imprint on Rome in one way or another: the Rome of the Republic, the Rome of the Empire, the Rome of the Popes, the Rome of the Liberals, the Rome of the Fascists, the Rome of the Italian Republic. In the 1900s, it was realised that the Church had not made a significant contribution to the great architecture of Rome for some time. Worse: the more significant structures of the past century were mostly built by the government of the Sardinian kingdom that conquered Rome and gave itself the fanciful, if geographically correct, name of ‘Italy’. A new church was needed, on a monumental scale, to be the age’s contribution to the great churches of Rome. Originally, the church was to be dedicated to St. James the Greater, but as preparations increased for the International Marian Year of 1924, it was decided the cult of the Immaculate Heart of Mary would take precedence instead. (more…)

NRC Handelsblad Goes ‘Compact’

Another broadsheet bites the dust

ONE OF THE most prominent newspapers in the Netherlands, NRC Handelsblad, switched from broadsheet to tabloid size this week. The newspaper claims it is returning to the ancestral format of its predeccesors, the Algemeen Handelsblad, the Amsterdam newspaper founded in 1828, as well as the Rotterdam Courant, founded in 1844. Those two papers merged in 1970 to form NRC Handelsblad, which is the seventh in circulation among the national newspapers of the Netherlands.

The evening newspaper has gained experience in tabloid-size printing since 2006 when it launched its morning compact edition, nrc.next, aimed at young, highly educated readers. Nrc.next has a Monday-Friday circulation of over 300,000, while NRC hovers around 240,000 on weekdays and 270,000 on Saturdays.

Canada’s Temporary Commons

Canada boasts one of the most imposing parliamentary complexes in the world, presiding from a lordly bluff in the federal capital of Ottawa. While I think the city could do with an overall Hausmannisation, the government of the Confederation is undertaking significant efforts to renovate the buildings on Parliament Hill.

While the House of Commons chamber is renovated, the dominion’s lower house will meet in a new temporary chamber (above) constructed in the inner court of the West Block, one of a pair of high Victorian Gothic structures that flank the main parliament building. The restoration will take five to seven years, after which the temporary chamber will be converted into parliamentary committee rooms.

The Commons in the Lords

IT WAS THE NIGHT of 10 May 1941. For nine solid months the Luftwaffe had thrown everything it had at the people of London, as Hitler hoped to bomb the English into despair and surrender. By early May, the Nazis realised the campaign had failed, and resources had to be directed elsewhere. The Blitz had to end, but on its final night, it hit one of its most precious targets. Twelve German bombs hit the Palace of Westminster that night, with an incendiary striking a direct hit at the House of Commons. The locus of Britain’s parliamentary democracy was consumed by flame and completely destroyed. (more…)

The New Zealand Half-Crown

In the 1930s, New Zealand devalued its pound in relation to sterling and a whole new series of coinage and bank notes were introduced under the authority of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand. The government commissioned the accomplished English numismatic artist George Kruger Gray to design the dominion’s new coinage, which included this very handsome half-crown. It’s a splendid convergence between Maori and European design, two cooperating strains of New Zealand’s national culture. The country’s shield of arms is topped by a Tudor crown and flanked by indigenous motifs. (more…)

Mamarazza

The photographs of “Manni” Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn

IT’S A CRACKING photo; the sort of thing guaranteed to irk the puritanical and bring a smile to the good-humoured. The thirteen-year-old Yvonne Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn takes a swig from a bottle while her brother Alexander, just twelve, sits with a half-smoked cigarette. Taken aboard the yacht of Bartholomé March off Majorca in 1955, the photographer was Marianne “Manni” Sayn-Wittgenstein-Sayn — the mother of Yvonne and Alexander — who’s known by her photographic soubriquet of “Mamarazza”. (more…)

The South Kensington Museum

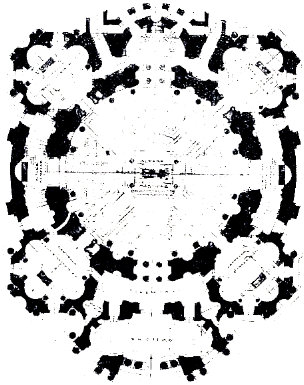

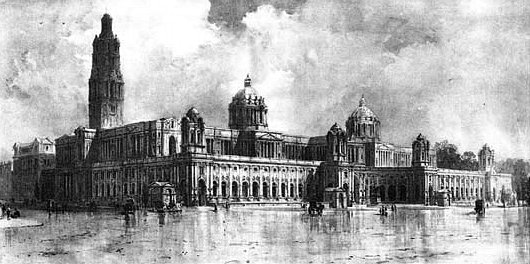

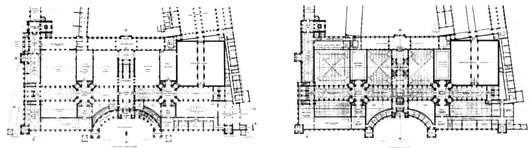

ANOTHER unbuilt project: this time a plan for completing the South Kensington Museum (or the Victoria & Albert as it’s now called) in the part of London which has become known as ‘Albertopolis’. The museum grew incrementally from its first foundation as the Museum of Manufactures after Prince Albert’s Great Exhibition of 1851.  The first design for the museum at its current site was by Gottfried Semper, but the plan was rejected as being too expensive. And so over the years the facilities grew incrementally and according to to haphazard plans. In the 1890s, eight architects were invited to submit proposals for a grand scheme completing the site under a unified architectural plan.

The first design for the museum at its current site was by Gottfried Semper, but the plan was rejected as being too expensive. And so over the years the facilities grew incrementally and according to to haphazard plans. In the 1890s, eight architects were invited to submit proposals for a grand scheme completing the site under a unified architectural plan.

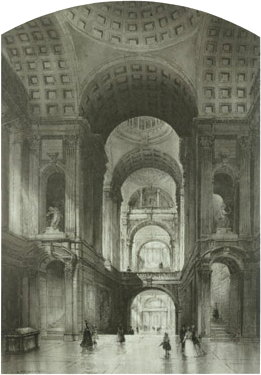

The judges cited this plan, by John Belcher, as the most original of the eight submissions. It’s a splendid composition in high Edwardian neo-baroque. The duality of the main domes is a particular confident touch, and harks back to Greenwich. Belcher’s baroque conception was not just an external factor: his interiors featured vast, sweeping spaces that would have been impressively monumental and reflecting the power and influence of the British Empire at its presumed cultural zenith.

“Although unsuccesful in the competition,” writes Iain Boyd Whyte of Edinburgh University, “this project attracted considerable praise in the professional journals for the plasticity of the main street facade and for its grand, Michelangelesque domes.” While the judges appreciated Belcher’s design, they worried about the cost of its execution, and awarded first prize to Aston Webb instead. His scheme was inaugurated in 1899 by the Queen-Empress, who renamed the institution ‘the Victoria & Albert Museum’ simultaneously.

I wonder if Belcher’s design would have gone better with the neighbouring Brompton Oratory, or if the Oratory benefits from having the V&A in a differing, brick-based style.

Old Master Paintings at Sotheby’s

A Florentine Artist, The Madonna & Child Enthroned Flanked by Saints Bridget & Michael

1450; Tempera on panel, 72 in. x 85 in.

QUITE A FEW interesting pieces up for auction today as part of Old Master Week at Sotheby’s in New York. The above altarpiece has been attributed to various artists. For much of its life was called the Poggibonsi Triptych, but scholars now believe it to be the work of the Master of Pratovecchio. This attribution was supported by no less an authority than Roberto Longhi, who (as the catalogue notes point out) “considered him an artist of note who contributed to the Florentine transition from the early fifteenth-century serenity and intimacy of Fra Angelico and Filippo Lippi to the more dynamic forms found later in the century.”

The altarpiece, commissioned from a certain Giovanni di Francesco in 1439, was acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum in California, which is now auctioning to raise funds for future acquisitions. (more…)

Christopher Rådlund

My first encounter with the art of Christopher Rådlund was through the website of a friend. Bill Coyle is a poet and translator whose knowledge of the Swedish language gives him an insight into the rich and ingenious Scandinavian world. His January 2010 New Criterion article on the Swedish “retrogarde” was a fascinating insight into what is arguably one of the most fruitful multi-disciplinary artistic movements in Europe today, left almost completely unreported upon in the English-speaking world. Bill’s website displays one of Rådlund’s painting.

Christopher Rådlund was born in Gothenburg, Sweden in 1970 and now lives and works in the Norwegian capital of Oslo. In muffled tones, his paintings exhibit a melancholic coldness, like a modern baring-down of Caspar David Friedrich. Here is a small selection of his haunting but beautiful work. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories