Arts & Culture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Christmas on College Green

There are some good (if brief) shots of the Irish House of Lords chamber in this Christmas ad for the Bank of Ireland, 0:35-0:45.

The former Irish Houses of Parliament on College Green in Dublin were the first purpose-built parliament building in the world, and were purchased by the Bank of Ireland after the parliament was abolished by the Act of Union in 1800.

Unfortunately a condition of sale was demolishing the elegant octagonal Commons chamber at the centre of the building, to prevent it being used in the effort to have the Act of Union repealed.

Sir Thomas Cusack (1505-1571) has the distinction of having at times served as the presiding officer of both the upper and lower houses of the Irish Parliament. From 1541-1543 he was as Speaker of the House of Commons, in which role some scholars argue he was a prime mover behind the legislation erecting Ireland as a kingdom.

In the following decade he served as Lord Chancellor of Ireland, presiding in the House of Lords, from 1551 until 1555 when revelations about his involvement in the creative finances of Sir Anthony St Leger’s viceregal regime brought about Sir Thomas’s dismissal and (temporary) imprisonment.

He returned to favour when the Earl of Sussex was appointed viceroy, but never again held high office.

Of course, all that was before this neoclassical building was erected, when Parliament met mostly in Dublin Castle.

Church of the Intercession

The huge and spacious interior of the Church of the Intercession, New York. One of Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue’s masterpieces; so much so that he decided to be interred in the north transept of the church.

Hamburger Abendblatt

The German advertising agency Oliver Voss created this series of ads for the Hamburger Abendblatt, Hamburg’s daily evening newspaper.

Oliver Voss have done web and print ads for the Abendblatt before but the illustrations in this series of posters strike a jovial pose, feeling perfectly contemporary while still informed by a sense of the 1950s.

The summery beach scene is my favourite.

Marinus Willett

In one of the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum’s American wing, behind the Tuckahoe-marble façade of the old Assay Office (moved here from Wall Street), hangs this portrait of Col. Marinus Willett of the Continental Army’s 5th New York Regiment.

Born in 1740, the second of thirteen children, Willett attended King’s College before being commissioned a lieutenant in a New York provincial regiment during the Seven Years’ War (or French and Indian War as it’s known more locally). (more…)

Mendicant Architecture in Mediaeval Oxford

An interesting video from two American academics on the subject of Mendicant architecture in mediaeval Oxford, with some three-dimensional theoretical reconstructions of the Dominican and Franciscan houses in the city.

Both orders returned to Oxford in the twentieth century. The Capuchins refounded Greyfriars in 1910 and it was recognised as a permanent private hall (PPH) of the University in 1957. Its end as an academic institution was announced sadly on its fiftieth anniversary in 2007, but Greyfriars continues as a Capuchin friary.

Blackfriars under the Dominicans is still going strong, exercising a triple function as a priory of the Order of Preachers, a house of studies for the English province of the Order, and a PPH of the University of Oxford.

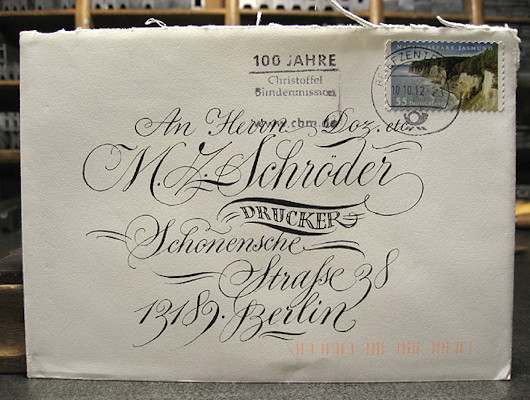

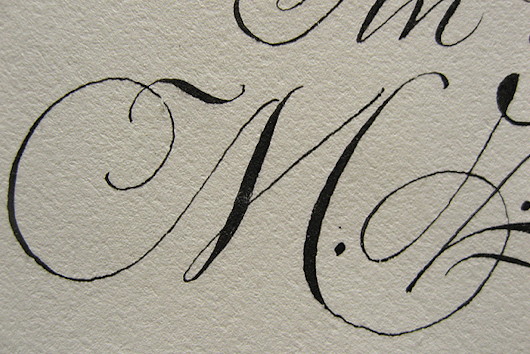

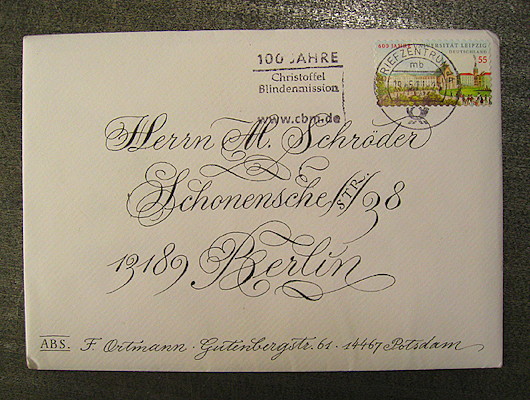

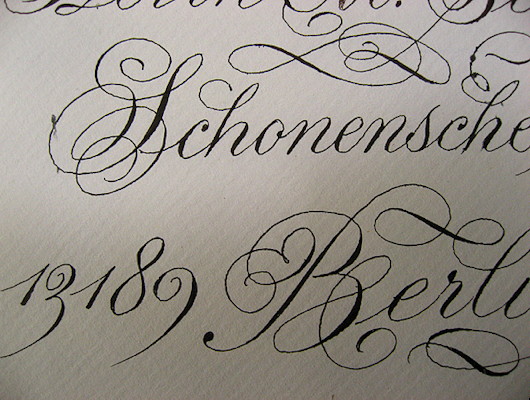

Calligraphic Correspondence

What a pleasure it must be to receive a letter from the designer Frank Ortmann (c.f. here), if the calligraphic correspondence received by printer Martin Z. Schröder is anything to go by. (See here & here.)

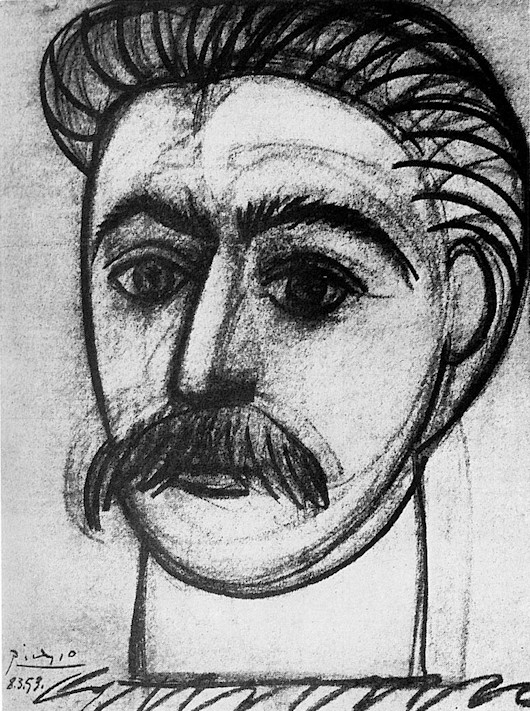

The Death of God the Father

When Stalin’s death was announced on Friday, 7 March 1953, Aragon called in Pierre Daix and rattled off a shopping list of features to honour Stalin in a special issue of Les Lettres françaises. […] Since Picasso had always refused to do a portrait of Stalin from a photograph, Daix sent a telegram to him at Vallauris saying, ‘Do whatever you want,’ and signed it ‘Aragon’.

Picasso’s drawing of Stalin, which depicted him as a curiously open-eyed young man, arrived at the very moment Les Lettres françaises went to press. Daix took the picture to Aragon. He admired it and said that the party would appreciate the gesture. While it was being set into the front page, office boys and typists crowded round the picture. Everyone thought it ‘worthy of Stalin’.

Daix was overjoyed to be the one who had commissioned Picasso’s first portrait of the Soviet leader and rushed it down to the printers. But a few hours later, when the edition had been run off, the mood in the building had completely changed to one of fear. Journalists from L’Humanité, passing by, spotted the drawing and cried out that it was unthinkable that any Communist publication should consider such a representation of ‘le Grand Staline’.

Pierre Daix promptly rang Aragon at his apartment; Elsa Triolet answered. She told him angrily that he was mad to have even thought of asking Picasso for such a drawing.

‘But really, Elsa,’ Daix broke in, ‘Stalin isn’t God the Father!’

‘Yes, he is, Pierre. Nobody’s going to reflect much about what this drawing of Picasso signifies. He hasn’t even deformed Stalin’s face. He’s even respected it. But he has dared to touch it. He has actually dared, Pierre, don’t you understand?’ […]

Antony Beevor & Artemis Cooper (1994, London)

Wall Street

Well, actually it’s Broad Street looking down past the New York Stock Exchange to Federal Hall, which itself is on Wall Street.

Most of Broad Street was originally a canal (hence its width) but in 1676 it was filled in and laid out as a street.

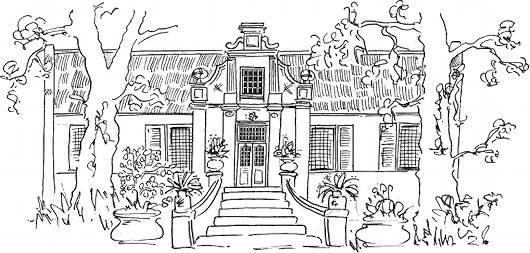

Muratie

The Stellenbosch estate of the artist Georg Paul Canitz

We had supper with Mr. Canitz, the painter, one Sunday night, by the light of candles in a fine Dutch candelabra, and drove back to Stellenbosch in moon light which had transformed the countryside into the most entrancing fairyland imaginable.

Great clumps of trees in unexpected places gave an eeriness to the white ribbon of road which stretched across the valley. The soft evening breeze of magic scents lulled us, and we drowsed to the hum of the car bearing us homeward.

That memory is still vivid to me so I shall turn from our Golden Road, and “…muse awhile, entoil’d in woofed phantasies.”

So the architect Rex Martienssen described a visit to Muratie, the home of the artist Georg Paul Canitz, in 1928. Canitz was a Saxon, born in Leipzig, where his parents had hoped he would pursue a military career. Both his zeal and talent as an artist appeared early on, and so he ended up at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. After further studies in Italy, Paris, and the Netherlands, a chest ailment drove him to the interior of Südwestafrika in 1907.

Canitz healed quickly in the dry air but could not find a cure for the striking beauty of the new world around him. His wife and children were summoned from Germany, and three years later he moved to Stellenbosch after falling in love with the “City of Oaks”.

Canitz devoted himself to his passions: riding, painting, and teaching (both at his own art school and at the University). Riding to a party at Knorhoek one day he stumbled upon the little house and farm at Muratie and was quickly enamored of the place. It wasn’t long before he had purchased it and moved his family there.

G P Canitz

At Muratie, the painter developed a further art: that of winemaking. In this he was assisted by the legendary Dr Perold — first chair of viticulture at Stellenbosch. Canitz became a pioneer of the pinot noir grapes which have since become a South African staple. Perhaps even more he developed the skills of a kind and generous host, for which he was well reputed throughout South Africa. He would welcome friends and guests — among them Martienssen and his architectural students as cited above — throughout the year. In warmer months they came for the swimming pool and the breezy stoep, while in winter a fire awaited, or perhaps a few rounds of strong drink in the Kneipzimmer.

I like to think this was Canitz’s favourite room at Muratie: bedecked with benches, the light streaming in through a stained-glass windows, and the walls covered in naturalistic painting as well as graffitied signatures and sayings in German, Afrikaans, French, and Greek.

The painter died in 1958, leaving Muratie to his daughter, who in 1987 sold it to members of the Melck family who had owned it from 1763 to 1897. (The house was first built in 1685.) I suspect Canitz would have greatly appreciated his handiwork being passed back to those who had looked after the place for many generations before him. The Melcks, unsurprisingly, have a great reverance for the history of the estate. They even go so far as to leave the cobwebs which have accrued go undisturbed and ask visitors to do likewise.

And, even today, the wine still flows!

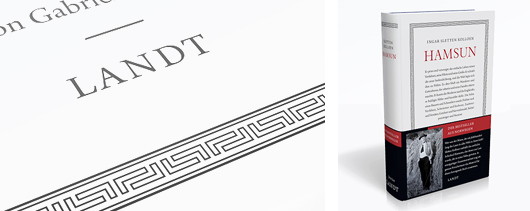

A Handsome Hamsun

Book design is a craft sadly neglected in the English-speaking world. In paperbacks, the French reign supreme, while the Teutons and Scandos design the most elegant hardcover books.

This German edition of Ingar Sletten Kolloen’s biography of Knut Hamsun was designed by Frank Ortmann for Landt Verlag, founded by the conservative popular historian Andreas Krause Landt (aka Andreas Lombard). Landt Verlag is now an imprint of Thomas Hoof’s Manuscriptum publishing firm. Hoof is better known for starting Manufactum, the retail company known for offering high-quality goods made through traditional methods.

I’ve never read any Hamsun myself though he has been strongly recommended by friends with reliable tastes. This Norwegian writer is widely read amongst the Germans but not so amongst the Anglos, and perhaps not surprisingly since he was an uncompromising Anglophobe and had praise for all things German.

Anglophobia was not his worse offence – a Nobel laureate, he ended up giving away the actual medal as a gift to Goebbels – but no less an unquestionable anti-Nazi than Thomas Mann hoped that “the stigma of his politics will one day be separated from his writing, which I regard very highly”.

The designer Frank Ortmann impressed the name of the publisher by incorporating letter-L initials into the rather Hellenic ornamental frame of the book. He’s also managed to banish the dreaded and ubiquitous barcode to a little banderole which also includes a short introductory text, preserving the visual integrity of the book itself.

Church of St James, Spanish Place

Always interesting to see a building you know well from a perspective you’ve never seen before, as in this photo of the Church of St James, Spanish Place, taken from Manchester Mews. The church somehow seems more imposing — like a great rounded keep.

A few months ago I was corralled into some favour or other that required a bit of muscle to move this there and whatnot, the payoff of which was it afforded an opportunity to explore the triforium of this Marylebone church and see the interior of the building from an entirely new vantage point.

It also meant being able to view in better detail the beautiful stained glass windows — many of them the gift of various Spanish royals, given that this parish originates as the chapel of the Spanish embassy (hence its name).

Speyer

This 1961 postage stamp celebrates the consecration, nine centuries earlier, of the Imperial Cathedral Basilica of the Blessed Virgin of the Assumption and Saint Stephen at Speyer — today the largest Romanesque church still standing.

Courtyard of the Palazzo Bonagia

A photograph of the courtyard of the Palazzo Bonagia, the Palermo residence of the Dukes of Castel di Mirto, looking towards the rococo staircase.

The steps, columns, and balustrades are of red marble from Castellammare del Golfo, all conceived in the mind of Andrea Giganti, priest-architect of the Sicilian baroque.

The building was bombed during the last war and reduced to a shell, but thorough if slow-going restoration work began in 2009 and continues.

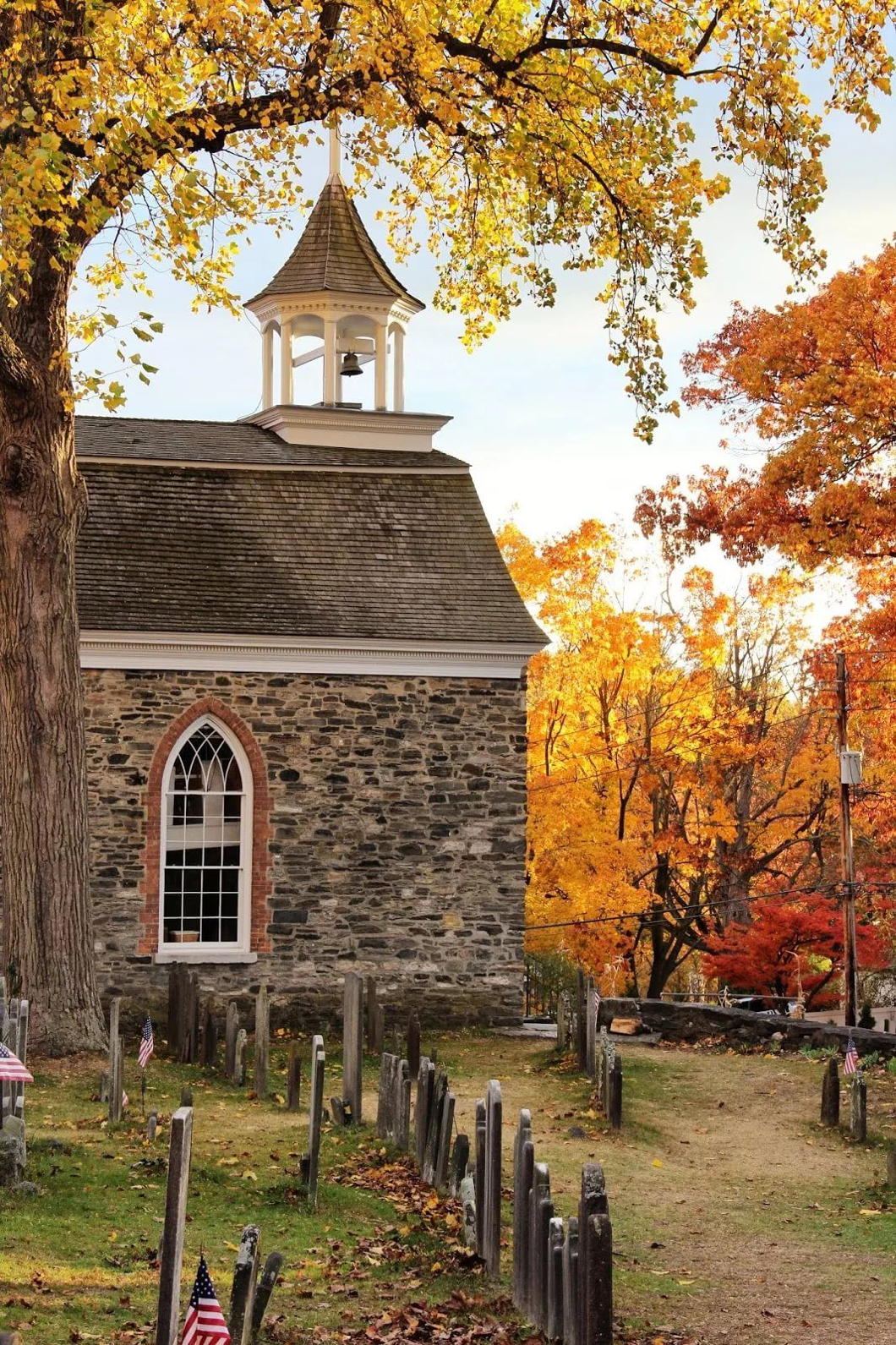

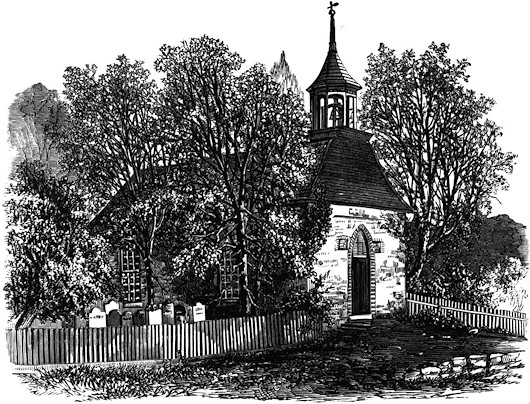

The Old Dutch Church of Sleepy Hollow

If there is any season which is plus New-Yorkaise que les autres then it must be autumn, and around the time of Hallowe’en in particular.

Thanks to the fertile imagination of Washington Irving, buried in the cemetery of the Old Dutch Church in Sleepy Hollow, the Hudson Valley is the spiritual home of this ancient Celtic feast now implanted in the New World.

The other day I dusted off the huge single-volume complete works of Irving – almost the size of an old Statenvertaling – and re-read his most famous tale, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”.

Irving describes the position of the Old Dutch Church:

The sequestered situation of this church seems always to have made it a favorite haunt of troubled spirits. It stands on a knoll surrounded by locust trees and lofty elms, from among which its decent whitewashed walls shine modestly forth, like Christian purity beaming through the shades of retirement. A gentle slope descends from it to a silver sheet of water bordered by high trees, between which peeps may be caught at the blue hills of the Hudson. To look upon its grass-grown yard, where the sunbeams seem to sleep so quietly, one would think that there at least the dead might rest in peace.

On one side of the church extends a wide woody dell, along, which raves a large brook among broken rocks and trunks of fallen trees. Over a deep black part of the stream, not far from the church, was formerly thrown a wooden bridge; the road that led to it and the bridge itself were thickly shaded by overhanging trees, which cast a gloom about it even in the daytime, but occasioned a fearful darkness at night. Such was one of the favorite haunts of the Headless Horseman, and the place where he was most frequently encountered.

The tale of the Headless Horseman is now, partly thanks to various popular reinterpretations of it, well known even outside the Hudson Valley. I remember as a wee lad growing up in that part of the world our Scout uniforms had a badge bearing the image of the “Galloping Hessian”.

Johannes Kip’s View of London

View and Perspective of the City of London, Westminster, and St James’s Park

This view of London and Westminster is most notable for the unique perspective it takes: a bird’s eye view from above the Duke of Buckingham’s house, later acquired by the Crown and now, as Buckingham Palace, the primary royal residence.

This printing of Kip’s view, which comes up for auction soon at Daniel Crouch Rare Books, may have been printed after 1726 as it incorporates Gibb’s steeple of St Martin-in-the-Fields.

‘Decisions, decisions…’

Rather horrifyingly, one of the proposals would have erected a monumental screen closing off the forecourt, completely spoiling the view of Edward Lovett Pearce’s beautiful façade.

Luckily the Bank chose Francis Johnston to harmonise the competition designs into the building we know today.

Voltaire’s Works Are Not Dead

They Are Alive: And They Are Killing Us

“It was a little after nine in the evening; the sun was setting, the weather superb. … Nothing is rare, nothing is more enchanting than a beautiful summer evening in St Petersburg. Whether the length of the winter and the rarity of these nights, which gives them a particular charm, renders them more desirable, or whether they really are so, as I believe, they are softer and calmer than evenings in more pleasant climates.”

The Soirées Saint-Petersbourg of Joseph de Maistre are philosophical dialogues that sometimes border on the mystical and delve into the dark recesses of human nature. They are eloquent, fascinating, and beautiful, traversing a broad range of subjects while hovering around evil and why it exists in the world.

In this extract from the Fourth Dialogue, the Count — generally taken to represent the author’s own view — objects to the young Chevalier citing Voltaire approvingly.

A critic might call it a rant; if so, it is at least a beautiful one:

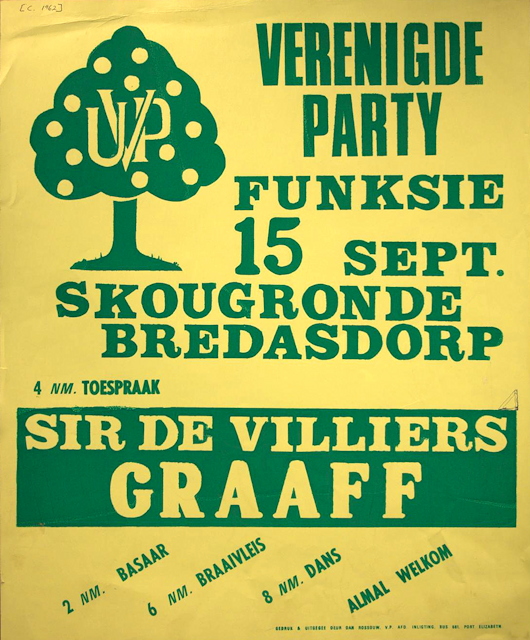

Party in the Overberg

Alongside a bazaar, a braai, and dancing, a speech by Sir De Villiers Graaff is the selling point of this poster advertising a United Party (Verenigde Party) get-together in the beautiful Overberg region of the Cape.

“Sir Div” was the inheritor of one of only twelve South African baronetcies and led his party from 1956 until 1977 when it merged with the Democratic Party of verligte ex-Nationalists to form a new entity.

The broadly centrist party had lost power to the republican Nats (creators of apartheid) in 1948, and suffered splits that led to the creation of the Liberal Party and the United Federal Party in 1953, the National Conservative Party in 1954, and the Progressive Party in 1959.

The party’s emblem was a happy little citrus tree.

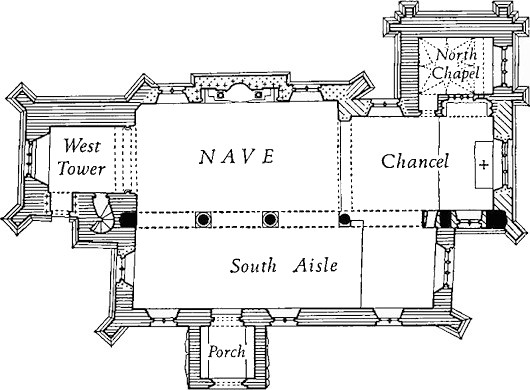

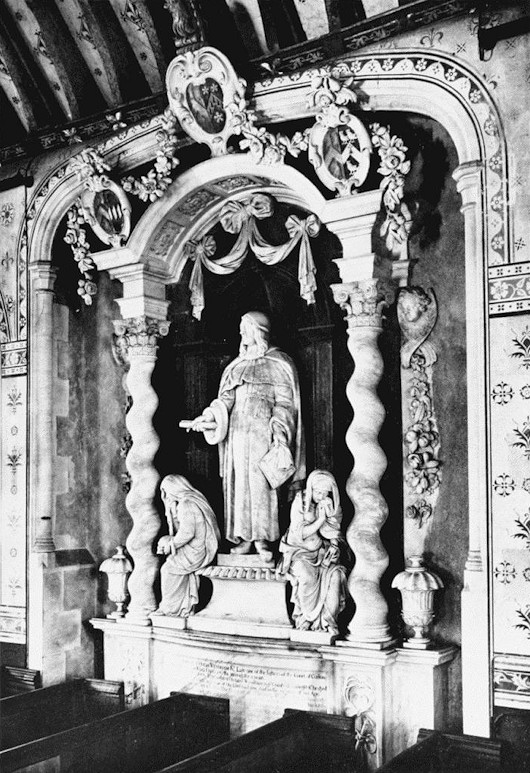

The Wyndham Monument, Silton

The charmingly haphazard Church of St Nicholas in Silton is home to what is arguably the finest funerary monument in Dorset not in a major church.

Sir Hugh Wyndham (1602–1684) lived through the difficult time of the Civil War and was first advanced in the law under Cromwell’s military dictatorship. It was the worst of both worlds for Wyndham, as the republican authorities never trusted him while after the Restoration his comfort with Cromwell meant he was deprived of office. Still, Charles II was no small-minded man, and after a royal pardon was granted Wyndham was appointed a Baron of the Exchequer and knighted.

The monument he left behind at Silton is is believed to be the earliest work of the Flemish sculptor Jan van Nost (also known as John Nost the elder). Sir Hugh is depicted in his judge’s robes, flanked by two mourning figures believed to represent his first and second wives. (The third wife is at least represented by having her arms impaled with Wyndham’s in one of the three heraldic sheilds gracing the monument’s surrounds.)

Nost’s sculpture was unveiled in the chancel of the parish church in 1692 but the Victorians thought it rather dominated the small sancutary. In 1869 a small recess was constructed in the north wall of the nave and the Wyndham monument was carefully moved there. The sculptor was also responsible for the monument to John Digby, 3rd Earl of Bristol, in Sherborne Abbey not far away, and one can see the parallels. The Earl, as it happened, married Rachel Wyndham, the younger daughter of Sir Hugh Wyndham.

Zeist’s Zest for Traditional Architecture

The Daniel Marotplein, a residential square in the town of Zeist, provides a fine recent example of traditional architecture in the Netherlands. Designed by the TU-Delft-trained architect Diederik Six, the twenty houses surround a green square named after the Huguenot craftsman and artist Daniel Marot some of whose handiwork is in the nearby Slot Zeist.

The slot (schloss/castle/house) is associated with the Protestant Moravian brotherhood who were invited to live nearby by Cornelis Schellinger in the mid-eighteenth century, and the Daniel Marotplein takes inspiration from the two squares of houses they lived in flanking the castle. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories