Art

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Hougaard Malan

South African Landscape Photographer

When I lived in South Africa I began to understand the deficiencies of photography. The scenery in which one we had the privilege of acting out “the foolish deeds of the theatre of our day” (as Mr Mbeki put it in one of his better speeches) was stunning, but on the few occasions I bothered to put my Leica to good use the results were disappointing. You’d look at a photograph that was admittedly beautiful but still think to yourself “But in real life it was a thousand times more beautiful than that!” Needless to say, my own lack of skill as a photographer is the most obvious cause.

Hougaard Malan, meanwhile, is one of the few photographers who manages to almost, nearly capture the beauty of the South African landscape. In each and every shot — and some of these places are well known to me — the scale and drama of the location shines forth.

“Growing up, my grandmother always gave me illustrated encyclopedias and books about earth’s natural history that were filled with fantastic landscape images,” Mnr Malan says. “I spent many afternoons paging through these books and marvelling at nature’s beauty. Few things in life made me feel more alive than a landscape that engaged all my senses – seeing the rhythmic rolling of waves in a bay, smelling the coastal flora, hearing and feeling the ocean crash against the cliffs and then tasting the salt in the air.”

Mnr Malan’s website can be found here but here is just a small sampling of the photographs of southern Africa and well beyond which this talented man has taken.

The Queen

1992; Oil on canvas, 96 in. x 60 in.

1950s Ireland, the Church, and the Arts

Sitting in Dublin Airport waiting for a flight last week I picked up a copy of the Irish Arts Review which featured a number of interesting pieces (including something by our own Dr John Gilmartin).

Among the articles was an interview with the artist and printmaker Alice Hanratty (born 1939), a member of the Aosdána as well as of its governing council the Toscaireacht.

It was interviewer Brian McAvera’s question to Ms Hanratty about Ireland in the 40s and 50s and her response that proved most interesting.

BMcA: Artists, nevermind historians, often talk about the dark days of the 1940s and 1950s in Ireland: petty, parochial, restrictive, dominated by the Catholic Church, politically conservative and sexually repressed. How did you see this period and was it in any way formative for you as an artist?

AH: I have some experience of the period in question and don’t really recognise the description that you quote.

As far as the arts are concerned you must remember that important Irish poets, dramatists, and novelists, and also painters and sculptors worked at that time. Brian Fallon discusses all that in his An Age of Innocence. As for ‘politically conservative, restrictive, dominated by the Catholic Church’ these I think are quite sweeping statements by people who did not actually live at that time and are re-stating a received perception which is inaccurate.

As for domination by the Catholic Church, to some degree people allowed themselves to be dominated. They were OK with it. It suited them. It provided answers about the imponderables such as death. Nor should it ever be overlooked that the vicious war waged against the Irish people and the practice of their religion by way of the penal laws have had a huge detrimental effect on the national psyche which is not yet dispersed even in the 21st century.

As for political conservatism (don’t start me), that was established by the Free State Government in the 1920s making a deliberate and successful move to stamp out any form of socialism that might develop. Of course the Church was pleased to be of help there, but was not the instigator. President Higgins made reference to this period in one of his 1916 commemoration addresses, so anyone seeking enlightenment in these matters would find it there.

Were the 1940s and 1950s influential for me as an artist? No. I was too young and was not looking outwards for inspiration.

Marinus Willett

In one of the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum’s American wing, behind the Tuckahoe-marble façade of the old Assay Office (moved here from Wall Street), hangs this portrait of Col. Marinus Willett of the Continental Army’s 5th New York Regiment.

Born in 1740, the second of thirteen children, Willett attended King’s College before being commissioned a lieutenant in a New York provincial regiment during the Seven Years’ War (or French and Indian War as it’s known more locally). (more…)

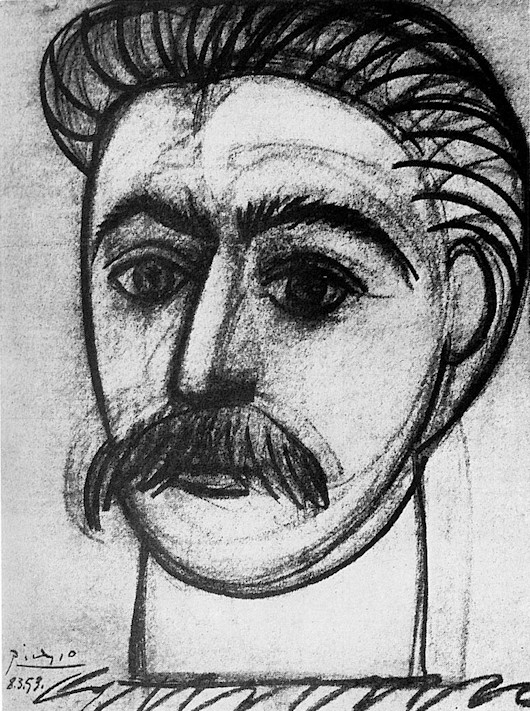

The Death of God the Father

When Stalin’s death was announced on Friday, 7 March 1953, Aragon called in Pierre Daix and rattled off a shopping list of features to honour Stalin in a special issue of Les Lettres françaises. […] Since Picasso had always refused to do a portrait of Stalin from a photograph, Daix sent a telegram to him at Vallauris saying, ‘Do whatever you want,’ and signed it ‘Aragon’.

Picasso’s drawing of Stalin, which depicted him as a curiously open-eyed young man, arrived at the very moment Les Lettres françaises went to press. Daix took the picture to Aragon. He admired it and said that the party would appreciate the gesture. While it was being set into the front page, office boys and typists crowded round the picture. Everyone thought it ‘worthy of Stalin’.

Daix was overjoyed to be the one who had commissioned Picasso’s first portrait of the Soviet leader and rushed it down to the printers. But a few hours later, when the edition had been run off, the mood in the building had completely changed to one of fear. Journalists from L’Humanité, passing by, spotted the drawing and cried out that it was unthinkable that any Communist publication should consider such a representation of ‘le Grand Staline’.

Pierre Daix promptly rang Aragon at his apartment; Elsa Triolet answered. She told him angrily that he was mad to have even thought of asking Picasso for such a drawing.

‘But really, Elsa,’ Daix broke in, ‘Stalin isn’t God the Father!’

‘Yes, he is, Pierre. Nobody’s going to reflect much about what this drawing of Picasso signifies. He hasn’t even deformed Stalin’s face. He’s even respected it. But he has dared to touch it. He has actually dared, Pierre, don’t you understand?’ […]

Antony Beevor & Artemis Cooper (1994, London)

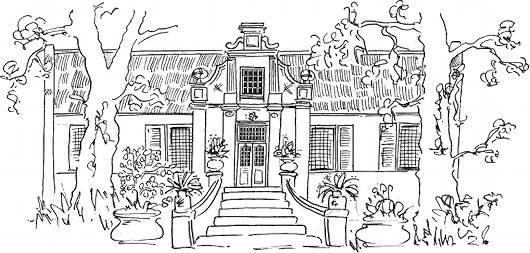

Muratie

The Stellenbosch estate of the artist Georg Paul Canitz

We had supper with Mr. Canitz, the painter, one Sunday night, by the light of candles in a fine Dutch candelabra, and drove back to Stellenbosch in moon light which had transformed the countryside into the most entrancing fairyland imaginable.

Great clumps of trees in unexpected places gave an eeriness to the white ribbon of road which stretched across the valley. The soft evening breeze of magic scents lulled us, and we drowsed to the hum of the car bearing us homeward.

That memory is still vivid to me so I shall turn from our Golden Road, and “…muse awhile, entoil’d in woofed phantasies.”

So the architect Rex Martienssen described a visit to Muratie, the home of the artist Georg Paul Canitz, in 1928. Canitz was a Saxon, born in Leipzig, where his parents had hoped he would pursue a military career. Both his zeal and talent as an artist appeared early on, and so he ended up at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. After further studies in Italy, Paris, and the Netherlands, a chest ailment drove him to the interior of Südwestafrika in 1907.

Canitz healed quickly in the dry air but could not find a cure for the striking beauty of the new world around him. His wife and children were summoned from Germany, and three years later he moved to Stellenbosch after falling in love with the “City of Oaks”.

Canitz devoted himself to his passions: riding, painting, and teaching (both at his own art school and at the University). Riding to a party at Knorhoek one day he stumbled upon the little house and farm at Muratie and was quickly enamored of the place. It wasn’t long before he had purchased it and moved his family there.

G P Canitz

At Muratie, the painter developed a further art: that of winemaking. In this he was assisted by the legendary Dr Perold — first chair of viticulture at Stellenbosch. Canitz became a pioneer of the pinot noir grapes which have since become a South African staple. Perhaps even more he developed the skills of a kind and generous host, for which he was well reputed throughout South Africa. He would welcome friends and guests — among them Martienssen and his architectural students as cited above — throughout the year. In warmer months they came for the swimming pool and the breezy stoep, while in winter a fire awaited, or perhaps a few rounds of strong drink in the Kneipzimmer.

I like to think this was Canitz’s favourite room at Muratie: bedecked with benches, the light streaming in through a stained-glass windows, and the walls covered in naturalistic painting as well as graffitied signatures and sayings in German, Afrikaans, French, and Greek.

The painter died in 1958, leaving Muratie to his daughter, who in 1987 sold it to members of the Melck family who had owned it from 1763 to 1897. (The house was first built in 1685.) I suspect Canitz would have greatly appreciated his handiwork being passed back to those who had looked after the place for many generations before him. The Melcks, unsurprisingly, have a great reverance for the history of the estate. They even go so far as to leave the cobwebs which have accrued go undisturbed and ask visitors to do likewise.

And, even today, the wine still flows!

Johannes Kip’s View of London

View and Perspective of the City of London, Westminster, and St James’s Park

This view of London and Westminster is most notable for the unique perspective it takes: a bird’s eye view from above the Duke of Buckingham’s house, later acquired by the Crown and now, as Buckingham Palace, the primary royal residence.

This printing of Kip’s view, which comes up for auction soon at Daniel Crouch Rare Books, may have been printed after 1726 as it incorporates Gibb’s steeple of St Martin-in-the-Fields.

Master Mitsui’s Ink Garden

Daniel Mitsui is one of the most interesting artists out there, exhibiting a wide range of influences from the Celtic to the Oriental. Among his latest works is an ink drawing on a Catholic theme. As Daniel explains:

I received a commission to create a Catholic religious drawing in a Chinese style. These explorations into artistic traditions outside of European Christendom are always exciting, and China was new territory for me. When developing the concept for the project, I looked to one of the early missionaries to China, the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci.

Some time in the very early 17th century, Ricci gifted four European prints to the Chinese publisher Cheng Dayue: two engravings by Anthony Wierix from a series illustrating the Passion and Resurrection of Christ, another by the same artist reproducing the painting of the Virgin of Antigua in Seville Cathedral, and one by Crispin De Pas the Elder from a series illustrating the life of Lot.

Master Cheng copied these images into his Ink Garden, a model book of illustrations and calligraphy. The missionary saw this as a good opportunity to disseminate lessons in Christian doctrine and morality among the Chinese population.

Continue reading here.

St Mary Redcliffe

The Church of St Mary Redcliffe in Bristol was famously described by Elizabeth Tudor as ‘the fairest, goodliest, and most famous parish church in England’.

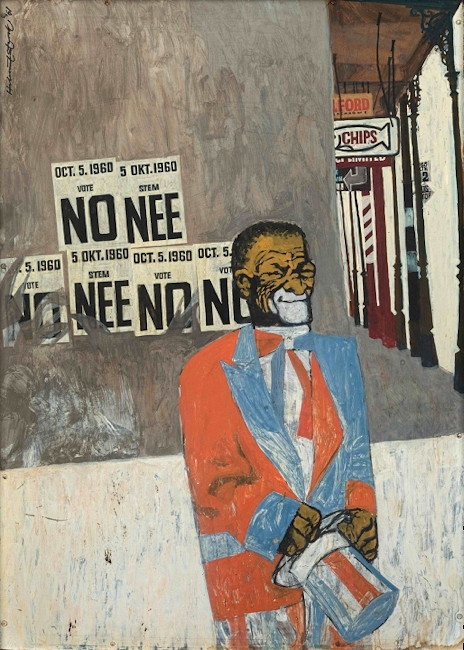

Alles Sal Reg Kom

1961; Acrylic on board, 34.8 in. x 24.8 in.

A man festively attired in a Tweede Nuwejaar outfit in patriotic colours (orange, white, and blue) stands in front of a side wall in Cape Town bearing monarchist posters urging voters to vote ‘No’ in the 1960 republic referendum.

The painting’s title – Alles Sal Reg Kom – means “everything will be alright”.

Darkness

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day,

And men forgot their passions in the dread

Of this their desolation; and all hearts

Were chill’d into a selfish prayer for light:

And they did live by watchfires—and the thrones,

The palaces of crowned kings—the huts,

The habitations of all things which dwell,

Were burnt for beacons; cities were consum’d,

And men were gather’d round their blazing homes

To look once more into each other’s face;

Happy were those who dwelt within the eye

Of the volcanos, and their mountain-torch:

A fearful hope was all the world contain’d;

Forests were set on fire—but hour by hour

They fell and faded—and the crackling trunks

Extinguish’d with a crash—and all was black.

The brows of men by the despairing light

Wore an unearthly aspect, as by fits

The flashes fell upon them; some lay down

And hid their eyes and wept; and some did rest

Their chins upon their clenched hands, and smil’d;

And others hurried to and fro, and fed

Their funeral piles with fuel, and look’d up

With mad disquietude on the dull sky,

The pall of a past world; and then again

With curses cast them down upon the dust,

And gnash’d their teeth and howl’d: the wild birds shriek’d

And, terrified, did flutter on the ground,

And flap their useless wings; the wildest brutes

Came tame and tremulous; and vipers crawl’d

And twin’d themselves among the multitude,

Hissing, but stingless—they were slain for food.

And War, which for a moment was no more,

Did glut himself again: a meal was bought

With blood, and each sate sullenly apart

Gorging himself in gloom: no love was left;

All earth was but one thought—and that was death

Immediate and inglorious; and the pang

Of famine fed upon all entrails—men

Died, and their bones were tombless as their flesh;

The meagre by the meagre were devour’d,

Even dogs assail’d their masters, all save one,

And he was faithful to a corse, and kept

The birds and beasts and famish’d men at bay,

Till hunger clung them, or the dropping dead

Lur’d their lank jaws; himself sought out no food,

But with a piteous and perpetual moan,

And a quick desolate cry, licking the hand

Which answer’d not with a caress—he died.

The crowd was famish’d by degrees; but two

Of an enormous city did survive,

And they were enemies: they met beside

The dying embers of an altar-place

Where had been heap’d a mass of holy things

For an unholy usage; they rak’d up,

And shivering scrap’d with their cold skeleton hands

The feeble ashes, and their feeble breath

Blew for a little life, and made a flame

Which was a mockery; then they lifted up

Their eyes as it grew lighter, and beheld

Each other’s aspects—saw, and shriek’d, and died—

Even of their mutual hideousness they died,

Unknowing who he was upon whose brow

Famine had written Fiend. The world was void,

The populous and the powerful was a lump,

Seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless—

A lump of death—a chaos of hard clay.

The rivers, lakes and ocean all stood still,

And nothing stirr’d within their silent depths;

Ships sailorless lay rotting on the sea,

And their masts fell down piecemeal: as they dropp’d

They slept on the abyss without a surge—

The waves were dead; the tides were in their grave,

The moon, their mistress, had expir’d before;

The winds were wither’d in the stagnant air,

And the clouds perish’d; Darkness had no need

Of aid from them—She was the Universe.

This year — 2016 — will be the two-hundredth anniversary of the Year without a Summer, caused by the eruption of Mount Tambora in the Dutch East Indies the year before.

The extremely high levels of volanic material in the atmosphere led to darker skies which meant colder temperatures and failed harvests. Brown snow was reported in Hungary and red snow in Italy.

But the abnormalities in the sky were also responsible for the spectacular sunsets that inspired artists like Caspar David Friedrich and J M W Turner and the unceasing rain that provoked Mary Shelley to write Frankenstein and Lord Byron to write ‘Darkness’.

It’s no coincidence that, soon after this year of darkness, John Polidori published his book The Vampyre and the modern concept of this undead creature began to haunt the gothic imagination.

The Accession

c. 1911; Oil on canvas, 68 in. x 76.9 in.

A triumphant painting, but a last hurrah. The central figure is Sir Nevile Wilkinson, the last ever Ulster King of Arms & Principal Herald of Ireland, exercising the duties of his office by proclaiming the accession of the new king at Dublin Castle.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty and its legislative acts neglected to make provision for transferring this ancient office to the new Irish Free State, but Sir Nevile carried on regardless for nearly two decades, even issuing two dozen grants of arms on the day before his death in 1940.

After his death, the Oireachtas created the office of the Chief Herald of Ireland to continue the granting of arms, and in some sense the Chief Herald is a spiritual successor to the Ulster King of Arms.

View from a Window

1830; Oil on canvas, 15½ in. x 13½ in.

I love the underappreciated Biedermeier, whether in art or literature, and this is a very Biedermeier painting.

The painter’s father, Charles de Moreau, was an architect – indeed he designed the very building that the son depicts here. As it happens, the painting now hangs in the Wien Museum am Karlsplatz, across from the main building of the Imperial & Royal Polytechnic Institute (now the Vienna University of Technology) which his father also designed.

Nikolaus painted this scene when he was twenty five, and he died just four years later not having reached his thirtieth year.

Interior of the Groote Kerk

1916; Oil on canvas, 29½ in. x 24½ in.

Though the painting is just a hundred years old, Gwelo Goodman depicted the scene as if in the late seventeenth century — when the Groote Kerk was first built.

While the body of the church was replaced in the 1840s, the elders of this most senior Nederduits Gereformeerde gemeente wisely kept the stunning baroque pulpit, the work of the Cape’s greatest sculptor Anton Anreith.

No ‘Malvinas’ Here

Some difficulties of Latin place names in 1930s cartography

It’s no great secret I’m a lover of maps. When calling in to the Secretariat of State on the terza loggia of the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican the other day, I was very pleased to see the cartographic murals there, including the two hemispheres done by Ignazio Danti in the 1580s. Moving to the next interior offices, however, the visitor is greeted by a much more recent mappa mundi, dating from the 1930s, replete with the glamour of empire’s heydey. (more…)

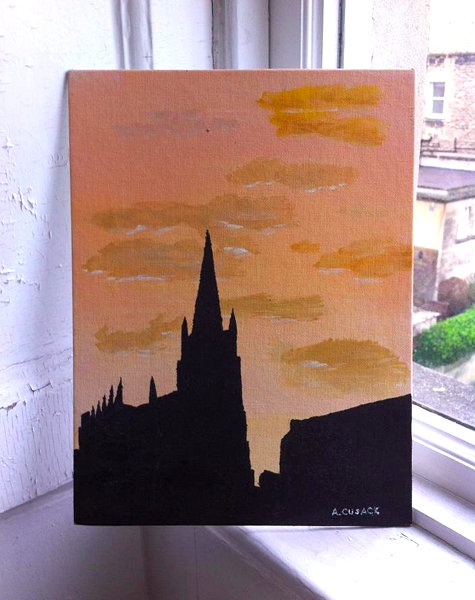

An Original Cusack

Much to my regret now, I never particularly learned nor pursued artistic skills, but this painting of St Patrick’s Church in Monaghan Town is one of the few fruits of art class from school days we’ve bothered preserving.

I think I was about 15 when this was done; the architecture was from a photo just to have something to stand out against the sunset. Our teacher was very good, but I was a poor student, and inattentive.

A Decade of Driehaus

A Carl Laubin capriccio pays tribute to the first decade of Driehaus laureates

THIS YEAR MARKED the tenth anniversary of the Driehaus Prize, the annual award honouring a living architect who has contributed to the field of traditional and classical architecture. To commemorate the first decade of the Prize, the architectural painter Carl Laubin was commissioned to produce a splendid capriccio depicting the works of the first ten Driehaus laureates.

As Witold Rybczynski, a member of the Driehaus panel of jurors, writes:

In the foreground is the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, a bronze miniature of which is presented to each laureate. It’s fun to try and identify the individual works in this large (5½ by over 8 feet long) painting. But what is more striking is that Laubin has created a convincing urban landscape solely out of landmark buildings.

That, of course, is the advantage of classicism: however it is interpreted, it is a tradition that manages to produce a more or less coherent whole. Even Abdel-Wahed El Wakil’s mosque, standing next to a Seaside beach house by Robert A. M. Stern, doesn’t look too out of place.

The Driehaus Prize was founded in part as a rival to the more publicised Pritzker Prize awarded to modernist architects. But, Mr Rybczynski points out, the fundamental nature of modernist structures is that they thrive only as a visual contrast to buildings constructed in a traditional style.

Can one imagine a similar townscape of Pritzker Prize winners? Well, maybe with the work of some of the early laureates—Pei, Bunshaft, Tange, Siza—but modern buildings need a background of nineteenth and early twentieth century urbanism to shine. A town made up of only signature buildings by our current generation of stars would resemble a carnival or a theme park—Pritzkerland.

I’ve often thought this of the United Nations headquarters in New York, which, when it was first built, must have stood out brilliantly as a bright and fresh harbinger of a better future, but which has been rendered altogether rather boring by the construction of neighbouring buildings of third-rate plate-glass modernist designs.

The UN headquarters on the East River and Lever House on Park Avenue were breakthrough buildings, but the increasing replacement of their traditional stone-clad or brick neighbours by cheap, tawdry modernist structures has exposed how reliant this type of architecture — even when well-conceived and properly executed — is on being surrounded by a contrasting style. (more…)

Beauty and Revolution

“Schönheit und Revolution: Klassizismus 1770-1820”

Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

WHEN IT COMES to styles, I am an omnivore. There are die-hard partisans, like Pugin, but I find the Baroque, the Gothic, the Classical — all are welcome to me. There is always some tiresome bore who, upon hearing any particular style of art or architecture praised, will immediately launch into a tirade against the more negative connotations commonly associated with that style. Gothic is close-minded! Mannerism is affected! The Biedermeier is bourgeois!

Well… ok… to an extent. But, in truth, we brush aside these pedants and appreciate whatever is beautiful wherever it is to be found. Art in its many forms is a giant sponge to squeeze and collect, savor, what comes out of it. (more…)

Grace Jones, Artist

Among the surprises in store at the Collectors’ Preview of the Olympia antiques fair on Monday night were two works by the actress Grace Jones. When I was a wee bairn, “A View to a Kill” was one of my favourite Bond films, and Jones played May Day, the frightening sidekick to Christopher Walken’s Zorin. Apparently Grace Jones studied art for a period, and Charles Plante Fine Arts has two pictures by her amongst their offering: ‘An Eskimo rowing a boat’ (Charcoal with mixed media, 49 inches by 43 inches) and ‘Untitled abstract composition 1983’ (Mixed media on paper, 60 inches by 67 inches).

Carl Laubin’s Architectural Fantasies

While the subjects of his works are varied, Carl Laubin has become best known for his architectural paintings. Born in New York in 1947, he veered into architectural painting when he was taken on by the London office of Richard Dixon — now part of Dixon Jones, the firm responsible for, among other projects, the Royal Opera House and the redesign of Exhibition Road. With an eye for detail, he has completed capriccios displaying the total built corpus of Hawksmoor, Cockerell, and, most recently, Vanbrugh, while the National Trust also commissioned him to paint a capriccio of all the houses currently within their care.

More of his work can be viewed at the website of Plus One Gallery, and a book of his paintings has been published by Philip Wilson. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories