Architecture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Potsdam’s City Palace to be Resurrected

THE OLD STADTSCHLOSS of Potsdam, destroyed by aerial bombing during the Second World War, will rise again next to the Old Market in the Brandenburg capital. The provincial government has decided to rebuild the old Stadtschloss to serve as a home for the Landtag, Brandenburg’s provincial parliament. While it was first conceived of building a modern building on the site, or having some reconstructed façades and others modern, a €20-million donation from the software entrepreneur Hasso Plattner has ensured the façades and massing of the building will follow the outline of the old stadtschloss. The interiors will be simple and modern, and to keep the costs down, much of the finer Baroque detailing of the façades will not be included. “I hope,” Herr Plattner said, “that the necessary compromises do not diminish the great impression overall.” (more…)

The Institute for the Study of the Ancient World

The Institute for the Study of the Ancient World commissioned Selldorf Architects, previously responsible for the renovation of the Neue Galerie on Fifth Avenue, to restore and upgrade the townhouse at 15 East 85th Street purchased to house the Institute. The house was built in 1899 but altered beyond recognition in 1928 after its purchase by Ogden Mills Reid, editor-in-chief of the New York Herald-Tribune. After the editor’s death, Mrs. Reid sold it to the American Jewish Committee, who used it as their headquarters until its sale to the Leon Levy Foundation, which endowed the creation of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University in 2006. (more…)

Scotland’s Three Parliaments

All of Them More Beautiful than the Current Parliament Building

IT IS ONE OF those curious aspects of Edinburgh: its multiplicity of parliament buildings. The Estaits of Parliament, as they were known in the old days — consisting of the three estates of prelates, lairds, and burghers — first met in the Great Hall of Edinburgh Castle in 1140, though the first gathering of which we have primary source material was at Kirkliston in 1235, during the reign of Alexander II. The body led a somewhat peripatetic existence, meeting wherever was convenient, and even met for a year in St Andrews, where the building which housed it is still known as Parliament Hall. Indeed, that august edifice is home to the proceedings of the Union Debating Society, where the germinal gasbags of Scotland, and indeed of all three kingdoms, first enter the fray of political discourse.

In 1997, nearly three-hundred years after the Parliament was abolished, it was decided to bring it back, albeit in much reduced form. Great were the rumours and discussions about what effect the return of legislative power might have on the country, and Edinboronians pondered where the body might be housed. There were obvious choices, and less obvious choices, but in the end the Westminster government decided to go for the choice that hadn’t been suggested at all and built one of the most heinous offences against the sensibilities of taste that the land has ever seen. And so, the fact is that Scotland has three beautiful parliament buildings, none of which it uses. (more…)

Cape Dutch California

While this Cape Dutch mansion sits in the hills of Montecito in California, it bears the name (and style) of an old Cape Peninsula town. “Constantia” was designed by Ambrose Cramer (take a peek at his nifty grave) in 1929 for Arthur & Grace Meeker, with landscaping by Lockwood deForest, Jr. The Meekers sold the house to the architect Jack Warner. In the late 1960s, Stewart & Katherine Abercrombie bought the place, and hosted the Dalai Lama on one of his trips to the United States. It was the subject of a 1979 feature in Architectural Digest. The place is for sale, currently listed at $17,900,000. (more…)

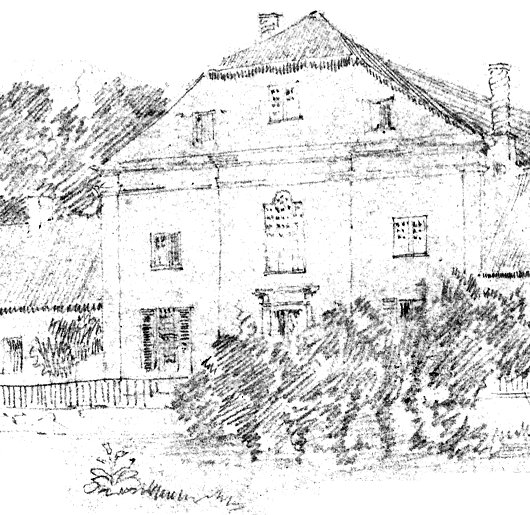

A little dilapidation goes a long way

Chelsea, Muttontown, L.I.

I have commented before about the perils of over-restoration, in which a building’s owner becomes a little too enthusiastic about its preservation and ends up with a building that, except in style, looks almost new. Chelsea sits on a 500-acre preserve in Muttontown, L.I. which has come into the hands of the government of Nassau (the county on Long Island in-between Queens County and Suffolk). The county has managed to maintain the house and its grounds at exactly the appropriate level: not plastering over every crack to make it ‘good-as-new’, nor neglecting it so it becomes structurally unsound, but rather allowing it to develop and age naturally. These photographs from the ever-capable James Robertson admirably display the house and its grounds, including its shallow canal-moat. (more…)

The National Assembly

Despite the longer history behind the original wing of South Africa’s Parliament House, when most people think of Parliament today they think of the 1983 wing that currently houses the National Assembly. The wing was designed by the architects Jack van der Lecq and Hannes Meiring in a Cape neo-classical style similar to the rest of the building, and it is actually quite a handsome composition despite the awkwardly proportioned portico, which is too tall for its width or two narrow for its height. (more…)

‘Starchitecture’ Assaults the Stately City

In the Heart of Old Valletta, Architect Renzo Piano Plans a Gate without a Gate, a Theatre with no Roof, and a Parliament on Stilts

“THE MOST HUMBLE City of Valletta” is the official title of Malta’s capital, which was founded in response to Moorish threats and withstood the onslaught of Nazi bombers. But ‘La Ċittà Umilissima’ is now facing a humiliation brought about by its own rulers, who have commissioned the modernist architect Renzo Piano to reshape the entrance to the oldest quarter of the city. ‘Starchitects’ like Piano are so called because their temporal success lies more on their ability to create hype about their sensational and novel designs than on the quality and timelessness of their work itself. Most notorious for collaborating with Richard Rogers on the despised Pompidou Center in Paris, Piano has re-envisioned Valletta’s city gate without a gate, placed a new Maltese parliament on stilts next to it, and developed plans for a roofless theatre on the bombed-out ruins of the Royal Opera House.

The foundation of the Maltese capital was initiated by the Order of Malta during its rule over the island, not long after the famous Ottoman attack of 1565 was repulsed. The city takes its name from Jean Parisot de Valette, one of the greatest men to have ever served as Prince & Grand Master of the Sovereign Military & Hospitaller Order of St. John of Jerusalem, and the knights’ impact on Valletta’s development have led some to call it “the city designed by gentlemen for gentlemen”. This stateliness led some to give ‘The Most Humble City’ its second moniker of ‘La Superbissima’ — the most proud. (more…)

Rouwkoop: An Old Cape Hodgepodge

We can deduce a lot about a power by looking at the structures it erects. The return to neo-classicism under Stalin after the earlier Russian deconstructivist architecture of the 1920s is telling, as is the almost universal (and only seemingly contradictory) adoption of socialist Bauhaus architecture for the headquarters of New York corporations in the post-war period, or the turn to Brutalism by the governments of numerous Western liberal countries in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. While the apartheid government adopted a guise of conservatism, its revolutionary re-ordering of South African society was so radical that, for example, the old Edwardian railway station in Cape Town was demolished and completely rebuilt in order to better accommodate the separation of the races.

When the Afrikaner Nationalist government was elected in 1948, it inherited one of the richest architectural traditions in the world. South African architecture, from the original Cape Dutch so praised by Ruskin, through the Cape Classical of the architect Thibault and the sculptor Anreith, and on to the attempt at a South African national style by Edwardian architects like Herbert Baker, the nation’s legacy of boukuns (building-art) is one of which any nation would be proud.

The Cape Dutch style has proved particularly versatile and easily reinterpreted in almost every age of South African history since Jan van Riebeeck planted the oranje-blanje-blou on these shores in 1652. Yet from 1948 until its final electoral demise in 1994 the National Party government erected almost no buildings in the “national style” of Cape Dutch or its aesthetic descendants. Instead, they built in the grim modernist style found everywhere else in the world, both in the liberal-capitalist West and the totalitarian-Marxist East. One need only consider the Nico Malan (now Artscape) in Cape Town, the Staatsteater in Pretoria, or the Theo van Wijk building at Unisa. (more…)

’n Indiese woning in die Moederstad

Kaapstad het ’n bietjie van die Himalajas

Twee versamelaars van suid-Asiatiese kuns het ’n subkontinentale woning in ’n Kaapstadse meenthuis geskep. Die huis was die onderwerp van ’n artikel deur Johan van Zyl in ’n onlangse uitgawe van Visi-tydskrif met hierdie foto’s van Mark Williams. Die algehele effek is ’n bietjie “over the top” vir my, maar die verleiding van die Oriënt sal nooit ophou. (Bo: ’n Paar van marmer-olifante uit Udaipur wagte by die hoofingang).

“In ’n nou keisteenstraat aan die rand van die Kaapse middestad staan ’n huis met ‘n geskiedenis” Mnr van Zyl skryf. “Toe dit in 1830 vir Britse soldate gebou is, het die branders nog digby die voordeur geklots, en nie lank daarna nie het Lady Anne Barnard hier sit en peusel aan ’n geilsoet vy wat ’n slaaf vir haar gepluk het, stellig van dieselfde boom wat nou in die huis se (nuwe) trippelvolume-glashart staan, ’n knewel met ’n vol lewe agter die blad.”

“’n Dekade of twee gelede het die reeds luisterryke geskiedenis van die huis ’n eksotiese dimensie bygekry toe twee toegewyde versamelaars — selferkende stadsjapies wat destyds in die modebedryf werksaam was — hier kom nesskop met hulle groeiende versameling Indiese oudhede.” (more…)

Government Buildings, Dublin

Image: GrahamH

On Upper Merrion Street at the end of Fitzwilliam Lane in Dublin sits a thoroughly Edwardian pile which has been given the thoroughly boring title of ‘Government Buildings’. The city ceased to be a legislative capital in 1800 when the Irish Parliament voted to abolish itself and join the United Kingdom, so government edifices constructed during the nineteenth century lacked the proud stateliness of the Grattan era. The Westminster parliament finally conceded the principle of Irish home rule in 1914 but disastrously suspended its implementation due to the First World War. In stepped the Irish Volunteers, Easter 1916, the IRB, and all that and by the time the Treaty of Versailles ended the conflict on the continent, Britain was up to her neck in troubles in Ireland. Events had intervened and the unimplemented concession of home rule proved insufficient to quell the dire situation.

Even so, the Government of Ireland Act 1920 partitioned the island and created a separate government for ‘Southern Ireland’ and ‘Northern Ireland’, each with its own devolved legislature. The old Irish Parliament House had been sold to the Bank of Ireland so there was a question as to where the two houses of the new Southern Irish body would convene. Eventually the government decided upon this building, the Royal College of Science, and it was commandeered for that purpose. (more…)

The Patriarchal Cathedral Basilica of Saint Mark the Evangelist, Venice

One of the readers over at the NLM sent in these photos of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice. The reason why St. Mark’s is usually referred to as a mere basilica is because for centuries this was not the seat of the Patriarch of Venice. From the seventh century, the Church of San Pietro di Castello was the cathedral of Venice, while St. Mark’s was the house church of the Doge, the elected duke of the Venetian aristocratic republic. It was only in 1807 that St. Mark’s was made the cathedral of Venice, and San Pietro di Castello reduced to co-cathedral status. But by the time St. Mark’s became a cathedral, everyone had already become accustomed to referring to it as “St. Mark’s Basilica”. (more…)

The Dovecot at Alphen (1989)

ESTABLISHED in 1714, Alphen is one of the legendary estates of the Cape Peninsula: Dr. James Barry duelled on the south terrace with Josias Cloete, and its guests include the illustrious names of Mark Twain, Cecil Rhodes, Field Marshal Smuts, and many more. While it once covered most of northern Constantia, the estate was much reduced during the twentieth century (and the M3 Simon van der Stel Freeway was built through its vineyards), Alphen, now a country-house hotel, is growing once again in the hands of the latest generation of Cloetes.

In 1989, the council authorities visited Alphen and declared that an electric substation must be built on the site or the hotel be forced to close. The ancient electric supply lines had, it turned out, been constructed illegally, and there was some danger of fire unless a substation was built on the Alphen property itself.

“Horrified we said there must be some other way,” writes Nicky Cloete-Hopkins (in the Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Society of South Africa). “There wasn’t, and Dudley [Cloete-Hopkins] said to Dirk [Visser, architect], who had been working with us for about five years by that time, ‘Disguise it as a folly or something.’”

“The ideal site for ours was … on the banks of the Diep River, at the end of a path leading from the 1772 water mill. It was in line with the strict grid pattern of the farm complex and gardens, much of which had been destroyed in the early and mid part of the twentieth century. We briefed Dirk to have fun, create a ‘folly’ and incorporate the Mitford-Barberton crucifix and family plaques from a Garden of Remembrance, demolished after the farm was subdivided.” Ella Lou O’Meara was later commissioned to do a family tree in tile for the Garden wall.

“Dirk suggested the dovecote — although we have had difficulty in keeping doves there. A little flamboyance has often enhanced the severity of the architecture at Alphen, and Dirk’s sketches for the proposed dovecote delighted us.”

Alphen and its great square of farm buildings had been designated a National Monument — akin to landmarking in the U.S. or listing a building in Britain — and so changes or additions needed to meet with the approval of certain historic advisors. “The builders had nearly completed their work when the then National Monuments Council sent representatives to inspect it. They commented that the design was not ‘honest’ and that we were fooling the public in making it look like a historic building.”

Mrs. Cloete-Hopkins wondered if the NMC wanted them to build something horrifically functional in the middle of a historic site for the sake of “honesty” or whether they wanted them to “erect something ultra-modern” like the new Louvre pyramid that was causing controversy at the time. “In any event it was too late to look at alternatives and I happily satisfied requirements by putting the date and the name of the architect and builder on the side of the building.”

A wise compromise and, like the dovecot/substation itself, informed by precedent.

Dino Marcantonio Hath a Blog!

Dino Marcantonio, habitual luncheon companion of your humble & obedient scribe, not to mention frequent commenter upon this little corner of the web, has entered into the realms of blogging himself. You can find his musings on the theory and practice of architecture here. They make for some pretty good reading so far.

An Old Dutch Holdout

The sign on the façade of No. 7 Wale Street, Cape Town in this 1891 photo informs us of its status as a police station in the two official languages of the day, English and Dutch, not Afrikaans. ‘Politie’ is the Dutch word for Police, while the Afrikaans is ‘Polisie’. Afrikaans only became an official language of South Africa in 1925, but was so alongside Dutch and English until 1961, when Dutch was finally dropped.

This beautiful old Dutch townhouse, with its typical dak-kamer atop, didn’t survive as late as 1961. The Provinsiale-gebou, home to the Western Cape Provincial Parliament, was built on the site in the 1930s. Those who viewed the 2009 AMC/ITV reinterpretation of “The Prisoner” might remember an outdoors nighttime city scene after the main character leaves a diner, with the street sign proclaiming “Madison Ave.” and plenty of yellow New York taxicabs streaming past. The large arches in the background are the front of the Provinsiale-gebou.

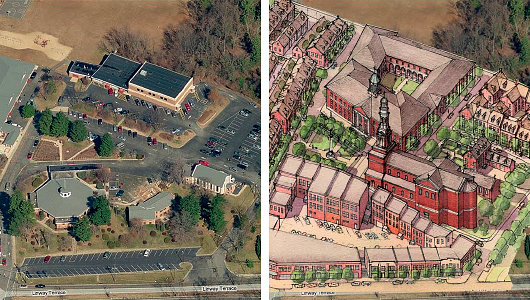

From Parking Places to People Spaces

Transforming a Suburban Parish into a Traditional Neighborhood

The widespread unsightliness of suburban development in the United States is one of the most significant counts one can hold against the country. The earliest suburbs, or indeed any that are pre-war, came out fairly well by contrast. One of the pleasures of living in Westchester is our system of verdant parkways (from the inter-war period) with arched stone bridges spanning the little creeks and carrying local thoroughfares over the road. The transformation of Long Island, after the Second World War, from countryside to row after row of mass-produced cookie-cutter homes was disastrous. (Levittown is my personal vision of Hell — identical homes completely divorced from any sense of livable social order.) Post-war suburban development combines ugliness, boringness, and an astonishing misuse of available land. Erik Bootsma, however, here presents a model proposal of how to transform the medium-sized property of a modern suburban parish church in Virginia into a small, livable neighborhood. (more…)

The Oratory as It Was Built

Since we explored Brompton Oratory as it might have been, here is the Oratory as it was built. The façade were finally completed in 1893 to a design by George Sherrin, with the dome following in 1894-95 by Sherrin’s assistant E. A. Rickards. How is the Oratory as depicted above different from the Oratory today? The fence and gates were replaced with a curved design at some date unknown to me, perhaps in response to a road-widening scheme.

The House of Assembly

Die Volksraad

The House of Assembly (always called the Volksraad in Afrikaans, after the legislatures of the Boer republics) was South Africa’s lower chamber, and inherited the Cape House of Assembly’s debating chamber when the Cape Parliament’s home was handed over to the new Parliament of South Africa in 1910. The lower house quite soon decided to build a new addition to the building, and moved its plenary hall to the new wing. (more…)

No. 82, Eaton Square

In it’s long history, the address of No. 82 Eaton Square in London has housed a Major-General of the East Indian Cavalry, a Lord Strafford, a Lord Bagot, an Earl of Dalhousie, an Earl of Clare, a Duke of Bedford, and Queen Wilhemina of the Netherlands — thankfully not all at once. It’s probably best know for its half-century as the Irish Club, a much-favoured drinking & smoking spot for the community of Gaels in London. The club was founded in 1947, with a number of pre-existing Irish clubs merging into it. George VI — grateful for the devoted service of the Irish who volunteered for his armed forces during the Second World War — heard that the club was in search of premises and asked the Duke of Westminster, one of the largest landowners in London, if he could help. The Duke provided the leasehold of No. 82 Eaton Square to the Irish Club for a nominal sum. (As it happens, the 4th Duke’s son served as a Unionist MP for Fermanagh & South Tyrone, and later in the Northern Irish Senate). (more…)

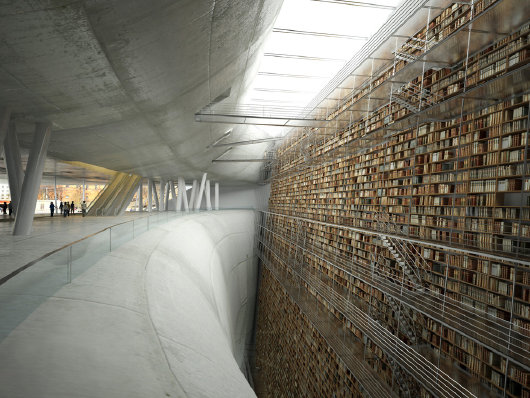

How Not to Build a Library

This computer-generated image has been doing the rounds on a variety of blogs across the internet. It depicts one of the numerous proposals for the extension of the Stockholm Public Library, this one drafted by a team from the Paris-Val de Seine architecture school. Over at the Long Now Blog, Alexander Rose calls it “awesome” and says “This design seems like it would lend itself well to a 10,000 year library”. As a monument this design is impressive — perhaps intimidating is the more appropriate word — but as a library it’s hard to conclude it would be anything other than a complete and total failure. And as for lasting 10,000 years, all those walkways to access the books look exceptionally brittle — I doubt they’d last a hundred years let alone ten thousand. (more…)

Baron Bossom’s Bridge

The Unbuilt ‘Victory Bridge’ Crossing the Hudson River at Manhattan

After the victory of America and her “co-belligerents” in the First World War, a temporary victory arch was erected out of wood and plaster to welcome the troops home from Europe. After the arch was dismantled, however, discussions soon arose on how to permanently commemorate the war dead of New York, with a surprising variety of suggestions made. A beautiful water gate for Battery Park was suggested, with a classical arch flanked by Bernini-like curved colonnades, so that a suitable place existed to welcome important dignitaries and visitors to New York. (Little did they know how soon the airlines would replace the ocean lines). Another proposal was for a giant memorial hall located at the site of a shuttered hotel across from Grand Central Terminal, while others suggested a bell tower.

An entirely different proposal, however, was made by the New York architect Alfred C. Bossom (later ennobled as Baron Bossom of Maidstone). Bossom, an Old Carthusian, was an Englishman by birth and eventually returned to his native land, where (in 1953) he gave away the future prime minister Margaret Roberts at her marriage to Denis Thatcher. He himself served in parliament from 1931 until 1959, excepting his wartime Home Guard service. Jokes were often made about his surname resembling both “bottom” and “bosom”. Upon being introduced to Bossom, Churchill jested “Who is this man whose name means neither one thing nor the other?” (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories