Architecture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The East Neuk of Fife

THE  EAST NEUK of Fife is one of my favourite little corners of the globe, in what is definitely my favourite country in the world. Here are a set of almost unspoilt little fishing villages with a quite localised architectural style that makes them instantly recognisable. The name of this little regionlet signifies its location as the east ‘nook’ of the Kingdom of Fife, that juts out into the North Sea.

EAST NEUK of Fife is one of my favourite little corners of the globe, in what is definitely my favourite country in the world. Here are a set of almost unspoilt little fishing villages with a quite localised architectural style that makes them instantly recognisable. The name of this little regionlet signifies its location as the east ‘nook’ of the Kingdom of Fife, that juts out into the North Sea.

Those concerned for this part of the world might be interested in signing up for the East Neuk of Fife Preservation Society, which has completed admirable work all over the East Neuk, and is currently considering the restoration of the gatehouse of Pittenweem Priory.

The Lion’s Gate

VISITORS TO CAPE TOWN may be surprised that, given the beauty and multiplicity of animals in the vicinity, the ‘Mother City’ has no zoo. There is actually a popular zoo at Tygerberg, twenty-four miles from Cape Town and less than ten miles from Stellenbosch, which is the only zoo in the province. But centuries ago — around 1700 — a ‘menagerie’ was founded in the Company’s Gardens in Cape Town which survived for over a hundred years.

François Valentijn, in his visit of 1714, noted the menagerie boasted a pair of ‘rheen’ or ‘rheebokken’ (probably kudu), a black rhinoceros, an eland, a ‘rossen bok’ (possibly a hartebeest), a hippopotamus, two lions, and a zebra. In the 1770s, the Swede Anders Sparrman noted the presence of many springbok, a warthog, some ostriches, and even a cassowary. The selection varied widely through the years, and given Cape Town’s status as ‘The Tavern of the Seas’ central to the European route to the Indies and the Far East, the zoo included not only African beasts but also some (like the Papuan cassowary) brought from the Orient.

In 1777, the notorious rake William Hickey ventured to extoll it as “the finest menagerie in the world, in which are collected the most extraordinary animals and birds of every quarter of the globe”. Less than fifteen years later, however, Lt. George Tobin of the Royal Navy described it as “a menagerie of some extent. It was but poorly supplied, there being but a few ostriches and some different kinds of deer.” Decades later, in February 1825, a traveller noted the menagerie in the pages of the Montly Magazine of London:

At the end of the Grand Walk, which is nearly three-quarters of a mile long, is the Company’s Menagerie, which is worth seeing, on account of a good-natured old lion, supposed to be the largest ever taken into captivity, and a tiger of immense size and power; there are several other specimens of African animals: but those are infinitely the largest of their species I ever saw—we have nothing that comes near them in England.

A spiritually inclined passer-through, the Rev. Henry Martyn, Chaplain to the Honourable East India Company, stated in 1832 that the “lion and a lioness, amongst the beasts, and the ostrich, led my thoughts very strongly to admire and glorify the power of the great Creator.” It was around that time that Sir Benjamin d’Urban, Governor of the Cape, granted land next to the menagerie for the erection of a building for the South African College, the germ of what would become the University of Cape Town. This was the beginning of what is now called the Hiddingh campus of UCT, the institution’s first home which continues alongside the main campus built on the Rhodes estate on the slopes of Devil’s Peak. The menagerie was shut in 1838 and the first building of the proto-UCT went up the next year in an exotic Egyptian Revival style.

The lion gates, however, are from earlier. They were built in 1805, probably by Thibault, with the lions & lionesses sculpted by the architect’s frequent collaborator Anton Anreith, also responsible for the magnificent pulpit in the Groote Kerk. The lionesses on the UCT side are original but the lions on the other side, curiously, were removed in 1873. In 1958 they were restored when Ivan Mitford-Barberton — arguably South Africa’s greatest sculptor after Anreith — created new beasts for the old perches. The gates are still there if you walk up the Government Avenue that bisects the Company’s Gardens, beautiful in the eye of this beholder in their immaculate, white, classical elegance.

Interesting Things Elsewhere

This determined Celt is gunning for Thabo

Kevin Bloom | The Daily Maverick

Ireland’s  Paul O’Sullivan took over as head of security at South Africa’s airport authority in 2001, and discovered something was wrong from the start: why didn’t the policeman on duty want to take a statement about the attempted theft of his baggage? Since then, his life has been a series of bizarre events leading him ever deeper into the most complex criminal network of the post-apartheid era, including the recent the trial and conviction of former national police chief Jackie Selebi. But O’Sullivan’s determined quest to expose crookedness isn’t over yet, and he now has former president Thabo Mbeki in his sights. read more

Paul O’Sullivan took over as head of security at South Africa’s airport authority in 2001, and discovered something was wrong from the start: why didn’t the policeman on duty want to take a statement about the attempted theft of his baggage? Since then, his life has been a series of bizarre events leading him ever deeper into the most complex criminal network of the post-apartheid era, including the recent the trial and conviction of former national police chief Jackie Selebi. But O’Sullivan’s determined quest to expose crookedness isn’t over yet, and he now has former president Thabo Mbeki in his sights. read more

The apparatus of state will simply ignore the government

‘Inspector Gadget’ | Police Inspector Blog

Police across England were told by the responsible minister of the democratically elected government that they must not chase performance targets any longer. “I can also announce today that I am also scrapping the confidence target,” said the Home Secretary, Theresa May, “and the policing pledge with immediate effect”. But the ‘senior management team’ of the West Yorkshire Police have stated they will go on no matter what the government says. read more

Has Christian Democracy reached a dead end?

Jan-Werner Mueller | Guardian.co.uk

The commentator completes a brief survey of the struggles of Christian Democracy in Germany and Europe today. The French leader Georges Bidault claimed that Christian Democracy meant “to govern in the centre, and pursue, by the methods of the right, the policies of the left”. But Christian Democracy’s brief French moment in the 1950s didn’t survive the return of de Gaulle, and Christian Democratic parties on the continent today face an existential crisis. read more

Also: Monsignor Ignacio Barreiro’s talk at the Roman Forum’s 2010 Summer Symposium, entitled The Problem of Christian Democracy will be made available online in audio form sometime in the coming months.

Deep in Shanxi, the most Catholic village in China

Anthony E. Clark | Ignatius Insight

Church after church dot the landscape and high steeples rise above small villages as they do in southern France. Passing through a narrow side road one arrives and is welcomed by three great statues at the village entrance: St. Peter holding his keys is flanked by Saints Simon and Paul. Thirty minutes before Mass the village loudspeakers, once airing the revolutionary voice of Mao and Party slogans, now broadcasts the rosary. Welcome to Liuhecun, the most Catholic village in China. read more

Look for me in the Cotswolds.

Dino Marcantonio

The apologists for modernist architecture have tried for a century to gain public acceptance of and appreciation for their horrors. While the elites have almost overwhelmingly been converted, the general populace around the world still sees that the Emperor has no clothes, and almost always prefers architecture that reflects the tried and true, the local and the natural. Alain de Botton, the Swiss essayist, ‘pop philosopher’, and former ‘writer-in-residence’ at Heathrow Airport, is the latest to give it a go, this time in the pages of the modernist Architectural Record. Dino Marcantonio provides a most useful fisking. read more

Canada is a French country

Andrew Coyne | Maclean’s

At the recent Canada Day celebrations on Parliament Hill, Canadian PM Stephen Harper spoke of “the steadfast determination and continental ambition of our French pioneers, who were the first to call themselves ‘Canadians.’” At other times he has spoken of Canada as having been “born in French,” of French as “Canada’s first language,” and, most famously, of Quebec City as “Canada’s first city,” its founding in 1608 as marking “the founding of the Canadian state.” While the sentiment may seen anodyne, moreover, the implications are radical. read more

A School Chapel on Long Island

St. Anthony’s High School, South Huntington, L.I.

“I have a general disgust for Catholic architecture since the 1950s,” says Brother Gary Cregan, the Franciscan friar who is principal of St. Anthony’s High School in South Huntington. The friar was quoted by the once-great New York Times in a 2008 article on the new chapel built by the Catholic school on Long Island, recently featured on the NLM blog. The Franciscans, according to the Times, “believe that the new chapel, with its soaring 30-foot ceilings, will teach teenagers that they are ‘worshiping God, not each other.'” Many of the chapel’s furnishings were bargain finds on eBay including the confessionals, the pews, a 110-year-old stained-glass window, and a century-old statue of St. Anthony. A new bell for the chapel’s tower would’ve cost $20,000, but Brother Gary (or “Mr. Cregan” as the newspaper referred to him) found an old one for $4,000. (more…)

Aldermania

Matt Alderman, already the subject of his own tag on this site, finally has a website of his own for Matthew Alderman Studios. You can investigate his prints, drawings, ecclesiastical furnishings, and liturgical objects. You can even ‘like’ it on Facebook.

Modern Scottish Architecture

Sydney Mitchell’s Royal Bank of Scotland, Kyle of Lochalsh

Among the surprisingly large pool of under-appreciated Scottish architects is Arthur George Sydney Mitchell. His Edinbornian works include Well Court in Dean Village, Ramsay Gardens in the Old Town, and his restoration of the Mercat Cross on the Royal Mile. Sydney Mitchell also did a number of branch commissions for the Commercial Bank of Scotland (which in 1959 merged with the National Bank to form the National Commercial Bank, which in turn merged into the Royal Bank of Scotland in 1979). (more…)

Libeskind Strikes Again, in Dresden

The controversial starchitect exacts Poland’s revenge on a German city

THE WAR WAS NOT kind to Dresden: the bombers of the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Army Air Force rained destruction on the Saxon capital, reducing much of the city to piles of rubble, and killing thousands upon thousands of innocent women and children in the process. One of the few buildings to survive the cataclysmic and morally reprehensible bombing campaign was the old garrison, which after the war was turned into a military museum.

Poland, whose unprovoked invasion by the Nazis sparked the Second World War, is exacting a curious revenge on neighbouring Germany, however. Daniel Libeskind, the controversial Polish starchitect, is building a monstrous addition to the Dresden Military History Museum that may not be a crime against humanity, but is undoubtedly a crime against architecture. (more…)

Carbuncle Alert in Queens

Our carbuncle alarm, which went haywire over the Brooklyn Museum’s offensive new entrance, has alerted us to a new monstrosity nearing completion in the adjacent borough. (more…)

A Palace on Princes Street

The North British & Mercantile Insurance Company, No. 64 Princes Street

PRINCES STREET IS the thoroughfare of the nation, and its sad decline during the second half of the twentieth century and only partial comeback since then are reflective of Scotland itself. The architects of Edinburgh’s New Town had no idea that Princes Street would evolve into a commercial avenue, and the street was originally laid out as a handsome row of Georgian townhouses, built between 1765 and 1800, facing Princes Street Gardens and the Old Town above behind them.

Almost immediately the mercantile and social nature of the street began to assert itself, with shops and traders setting themselves up in the converted basements and ground floors of townhouses. The New Club showed up at No. 86 Princes Street in 1837, coming from previous premises in St. Andrew’s Square and before that Shakespeare Square (where the former G.P.O. now stands).

As the Victorian era progressed, more and more of the Georgian townhouses were demolished and replaced with new buildings in the varying styles of age. It was just two years after Victoria’s death that an old company built a new headquarters in a brimming Edwardian baroque: the North British and Mercantile Insurance Company. (more…)

The Houses of Parliament, Dublin

The Physical Incarnation of Ireland’s Golden Age

THE OLD HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT in Dublin are probably at the top of my list of favourite buildings in the world. Now the headquarters of the Bank of Ireland, it has a long and varied history, and its exterior composition is one of surprising unity for a structure the components of which were designed by three architects. It is supposedly the first purpose-built parliament building in the world, and stands on the site of Chichester House, a stately home adapted for use by the Irish Parliament from the 1600s onwards.

The location, with a history dating back centuries, is just south of the Liffey river upon what was then known as Hoggen Green. A nunnery existed on the site which was supressed during Henry VII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries. A large private house was then built on the site, set back from the street, eventually known as Chichester House. (It likely incorporated some of the old convent’s structure). Among the esteemed inhabitants of the house were Sir George Carew, sometime Lord President of Munster, Sir Arthur Chichester, after whom the house was named, and the Anglican Bishop Edward Parry is known to have had a lease on the place during his lifetime.

The building must have been seen as holding some public significance, not only because it was located adjacent to the University of Dublin (of which Trinity College is the sole constituent institution), but it was home to the Irish Law Courts for a time beginning with the Michaelmas legal term of 1605. Towards the end of the seventeenth century, no later than October 1692, the Irish parliament began to meet at Chichester House on College Green. (more…)

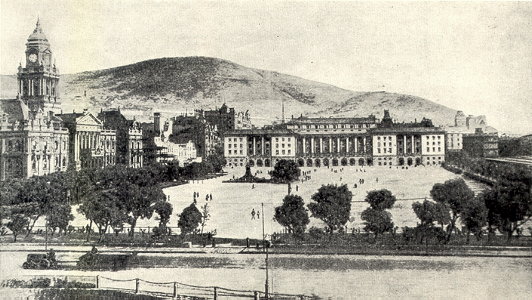

Unbuilt Cape Town: Municipal Offices

UNBUILT ARCHITECTURAL PROPOSALS fascinate me. Unfortunately most of the books documenting the more prominent examples of unbuilt buildings focus on space-age hyper-modernist ideas that never got off the drawing board, but these tend towards the tawdry and ridiculous. Far more interesting are the rejected proposals for buildings that did get built — for example the rival schemes to rebuild the Palace of Westminster after the 1834 fire — or this example of a proposal for a building never executed. I came upon these scheme thanks to the uploads of the Flickr user Berylmd. While Cape Town has a splendidly grand City Hall in an Edwardian Baroque style, the city fathers were unwise in providing insufficient space for the ever-blossoming municipal bureaucracy. This plan would have put a new municipal office building spanning the entire western side of the Grand Parade, replacing those little unremarkable market buildings whose existence on the square persists to this day. (more…)

The Versatility of the Cape Dutch Style

ORANJEZICHT IS ONE of my favourite parts of Cape Town, nestled in the bowl between Table Mountain and Signal Hill. Its name betrays it’s sloping location, which offers a view towards the Oranje bastion, one of the five of the Castle, which take their name from the titles of William, the Stadthouder of the United Provinces. The architecture is generally handsome, even if it often tends towards the Victorian. A few years ago, Cape Town Daily Photo featured a view (above) of the corner of Montrose Avenue and Bo-Oranjestraat in Oranjezicht. The late-autumn/early-winter street scene focusses on the Oranjezicht Carlucci’s, one of a small chain of delicatessens and wine shops founded in the mid-1990s.

The architecture of the shop is by no means in the strictest confines of the Cape Dutch style but is instead a more modern design influenced by the local architectural tradition of the Cape. While the Cape tradition is better known for larger country houses and wine-growing estates or small cottages, it’s just as useful a guide in the urban context. Dating the age of the building just by this photo would be tricky, as the region has some fairly convincing recent structures built in the old style (the dovecot at Alphen, for example), but I’d wager it’s 1900s-1910s construction that underwent a substantial renovation in the 1990s. (more…)

Swellendam Church Tower

In this video, the goodly folk of Swellendam demonstrate for us how not to remove a rotted wooden church tower. The little kid is a hoot — “It will get vrot and it will fall off on someone’s head”. The church tower has since been restored to its original iconic profile.

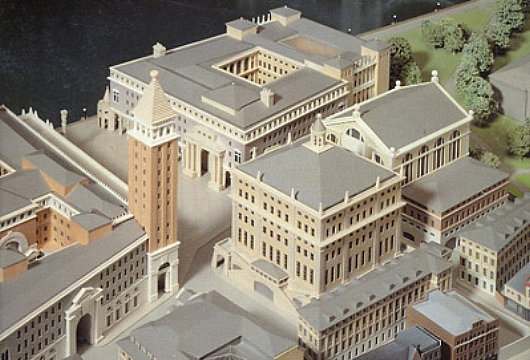

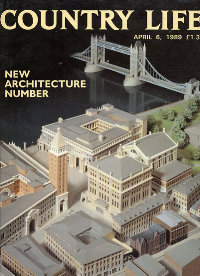

London Bridge City: The Neo-Venetian Scorned

JOHN SIMPSON AND Partners  are one of the most prominent firms promoting classical architecture and urban design in Great Britain. They are perhaps most widely known for the work they did on the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace, as well as for the rejected scheme to redevelop Paternoster Square next to St. Paul’s Cathedral. Contemporary to their ultimately unsuccessful Paternoster Square bid was another ambitious scheme, Phase Two of the London Bridge City development. For Phase Two, Simpson composed a miniature Venice-on-the-Thames complete with Piazza San Marco and ersatz campanile. There seems, however, to be something just a bit un-English about the whole project. There are numerous examples of Ruskinian Venetian buildings throughout Britain, and indeed the Commonwealth, but an entire complex of Anglo-Neo-Venetian seems a bit over-the-top. Still, one can’t deny preferring a touch of Simpson’s over-the-top Venetian to the glass-plated boredom developers usually offer the public.

are one of the most prominent firms promoting classical architecture and urban design in Great Britain. They are perhaps most widely known for the work they did on the Queen’s Gallery at Buckingham Palace, as well as for the rejected scheme to redevelop Paternoster Square next to St. Paul’s Cathedral. Contemporary to their ultimately unsuccessful Paternoster Square bid was another ambitious scheme, Phase Two of the London Bridge City development. For Phase Two, Simpson composed a miniature Venice-on-the-Thames complete with Piazza San Marco and ersatz campanile. There seems, however, to be something just a bit un-English about the whole project. There are numerous examples of Ruskinian Venetian buildings throughout Britain, and indeed the Commonwealth, but an entire complex of Anglo-Neo-Venetian seems a bit over-the-top. Still, one can’t deny preferring a touch of Simpson’s over-the-top Venetian to the glass-plated boredom developers usually offer the public.

London Bridge City, Phase Two was proposed in the aftermath of the hugely popular speech by Prince Charles in which he condemned a planned modernist addition to the National Gallery as a “monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend”. A bit of a donnybrook erupted between the architectural elite on the one hand (supporting the carbuncle) and the public on the other (supporting the Prince of Wales) and many a property developer was caught in the rhetorical crossfire. LBC’s backers decided, as an act of pragmatism, to come up with three radically different schemes in different styles and present them for consideration. (more…)

Cape Town’s Other St. George’s

The Greek Orthodox Cathedral of Saint George

If you hear of “St. George’s Cathedral” in Cape Town, you naturally think of the big stone colossus at the bottom end of the Company’s Garden smack dab in the middle of the Mother City. There is, however, another St. George’s Cathedral, the Greek Orthodox Cathedral of St. George on Mountain Road in Woodstock. The Greek Cathedral was built in 1903–04, just a few years after Cape Town received its first Greek Orthodox priest, and expanded in 1983. Liturgies tend to be either in Greek or English, though there is an Afrikaans monastery at Robertson.

The Holy Archdiocese of the Cape of Good Hope was established in 1968 under the (Greek Orthodox) Patriarch of Alexandria and All Africa. The archdiocese covers the Western, Northern, and Eastern Cape provinces, the Orange Free State, KwaZulu-Natal, Namibia, Lesotho, and Swaziland.

I only ever knew one South African of Greek extraction (Dimitri! Not just a good egg, but a top-notch chef as well), but I assume that folks of Hellenic extraction enjoy the Mediterranean climate of Cape Town and its environs.

A New Scots Town in the Highlands

The 20th Earl of Moray teams up with Miami-based firm Duany Plater-Zyberk to plant a New Town of 10,000 inhabitants outside Inverness

BELEIVE IT OR not, Inverness is one of the fastest-growing cities in Europe, and a local landowner, the 20th Earl of Moray, has teamed up with Duany Plater-Zyberk, an American firm known for its traditional architecture and urbanist ideas, to help create a sustainable new town of 10,000 inhabitants near the “Capital of the Highlands”. Tornagrain will rest on a 200-hectare (500-acre) site on the A96 corridor between Inverness and Nairn. Much of the recent growth in the Highlands has been poorly managed, raising concerns of suburban sprawl and poor land management. Moray Estates, the land holding company of the Earl of Moray (pronounced ‘Murry’) has decided to take the lead by planning a new town in the best tradition of Scottish architecture and urban development. (more…)

The Old New York Observer Building

No. 54, East Sixty-fourth Street

“FOR 17 YEARS,” writes Peter W. Kaplan, “since The New York Observer entered city life in 1987, it has existed within a red brick and white-marble-stepped townhouse on East 64th Street.” Designed by Ernest Flagg and Walter B. Chambers during their brief partnership, No. 54 East Sixty-fourth Street (between Park & Madison) was built in 1907 as a private residence for Robert I. Jenks. The AIA guide accurately describes it as “four stories of delicate but unconvincing neo-Federal detail… a minor Flagg.” In 1947, the townhouse was converted into offices for the Near East Foundation, which was founded in 1915 to provide relief for Armenian refugees from the Ottoman Empire and later took on greater responsibilities in North Africa and the Levant. It was then bought by Arthur L. Carter, the founder and publisher of the New York Observer for use as the salmon-tinted newspaper’s headquarters.

In 2004, the Observer moved down to Broadway, two blocks south of the Flatiron Building (and just a few blocks up from The New Criterion whose founder, Hilton Kramer, was for nearly two decades the art critic for the Observer). The townhouse was sold by Carter to the Russian-born Janna Bullock, real estate developer & sometime Guggenheim foundation board member for $9.5 million in the year the newspaper moved out. In 2005, Bullock renovated the building and had it used at the Kips Bay Decorator Show House for the year before selling it on to the Irish investor Derek Quinlan for $18.74 million. Quinlan put it on the market for $36 million but last year the asking price was chopped to $27 million.

Twenty-five feet wide, five stories, and with over 10,000 square feet, No. 54 was probably the only newspaper headquarters to feature nine working fireplaces, rosewood panelling, and oak wainscoting. But the best feature, by a mile, is the splendid iron-railed staircase, which looks like it was lifted straight from Paris. Elegant and graceful, a rare century-old survival in Manhattan. (more…)

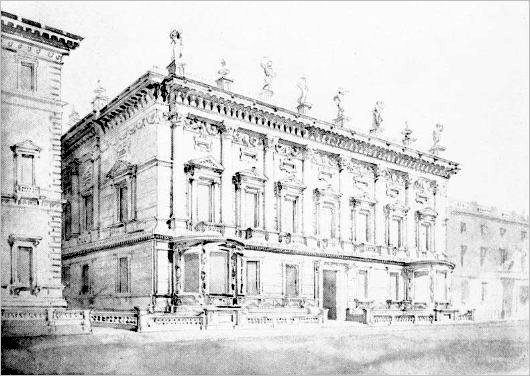

Cockerell’s Carlton Club

Charles Robert Cockerell is best known for designing both the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford and its Cambridge equivalent, the Fitzwilliam Museum. He is also, alongside William Henry Playfair, responsible for the twelve-columned National Monument that sits atop Calton Hill in Edinburgh — allegedly unfinished, though there is considerable debate over whether this is so. It’s not widely known, however, that the famous architect Cockerell completed a design for a new home for the Carlton Club on Pall Mall in London.

Originally Cockerell had declined the opportunity to submit a design, with such lofty names as Pugin, Wyatt, Barry, and Decimus Burton also declining the offer. A few years later, Cockerell nonetheless worked on this design for the Tory gentlemen’s club, which is superior to that conceived by another architect which was eventually built. Cockerell devised a “lofty Corinthian colonnade of seven bays” according to the Survey of London. “The columns have plain shafts, their capitals are linked by a background frieze of rich festoons, and the Baroque bracketed entablature is surmounted by an open balustrade with solid dies supporting urns and gesticulating statues.” (more…)

The Oriental Club

Stratford House, London

JUST STEPS AWAY  from Oxford Street, one of London’s busiest thoroughfares, rests a quiet little street called Stratford Place probably familiar only to Tanganyikans or Batswana seeking counsel from their countries’ high commissions. At the termination of the dead-end street sit the stately quarters of the Oriental Club: Stratford House. The club was founded in 1824, as British involvement and influence in both India and the Orient was waxing rapidly. General Sir John Malcolm, sometime Ambassador of His Britannic Majesty to the Court of the Peacock Throne (which is to say, Persia), coordinated the founding committee and advertised a club which would draw its members from “noblemen and gentlemen associated with the administration of our Eastern empire, or who have travelled or resided in Asia, at St. Helena, in Egypt, at the Cape of Good Hope, the Mauritius, or at Constantinople.” (more…)

from Oxford Street, one of London’s busiest thoroughfares, rests a quiet little street called Stratford Place probably familiar only to Tanganyikans or Batswana seeking counsel from their countries’ high commissions. At the termination of the dead-end street sit the stately quarters of the Oriental Club: Stratford House. The club was founded in 1824, as British involvement and influence in both India and the Orient was waxing rapidly. General Sir John Malcolm, sometime Ambassador of His Britannic Majesty to the Court of the Peacock Throne (which is to say, Persia), coordinated the founding committee and advertised a club which would draw its members from “noblemen and gentlemen associated with the administration of our Eastern empire, or who have travelled or resided in Asia, at St. Helena, in Egypt, at the Cape of Good Hope, the Mauritius, or at Constantinople.” (more…)

The New Yale Colleges

Yale University announced in 2008 that it would erect two new residential colleges in order to expand its undergraduate population without putting further strain on the twelve residential colleges that currently exist. Reportedly, Yale officials took a look at the new Whitman College at Princeton University, designed by traditional architect Demetri Porphyrios and decided even that wasn’t traditional enough. They commissioned Robert A. M. Stern, an architect who has, on occasion, proved exceptionally capable in traditional styles (the American Shingle style in particular), to design the two new colleges at the Connecticut university.

While the new colleges are currently being referred to as ‘North College’ and ‘South College’, there is little doubt that each college will find a generous benefactor who will endow it with funds and in return deign to allow the college to be named after the deep-pocketed soul.

The new colleges will, appropriately, be built in the Collegiate Gothic style, but will be faced in brick instead of stone. Brick facing in Gothic-style buildings always leaves one with a slight dissatisfaction, I’m afraid. Still, the decision to build in a traditional style is of course commendable.

For a commentary on the Collegiate Gothic of today, see this bit from Dino Marcantonio.

Here follow a few of the architect’s renderings of the new colleges. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Amsterdam November 26, 2024

- Silver Jubilee November 21, 2024

- Articles of Note: 11 November 2024 November 11, 2024

- Why do you read? November 5, 2024

- India November 4, 2024

Most Recent Comments

- on The Catholic Apostolic Church, Edinburgh

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

- on Why do you read?

- on Why do you read?

- on University Nicknames in South Africa

- on The Situation at St Andrews

- on An Aldermanian Skyscraper

- on Equality

- on Rough Notes of Kinderhook

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories