Arts & Culture

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Sag Harbor Cinema

For a film fan, to grow up in an American town with a small cinema is to win the lottery of life.

In my childhood, we had the advantage of two little movie houses within walking distance: the three-screen Bronxville Cinema and just a little bit further afield by foot the single-screen Pelham Picture House.

Fittingly, these two are now run together as the somewhat pretentiously titled but no-doubt quite useful ‘Picture House Regional Film Center’.

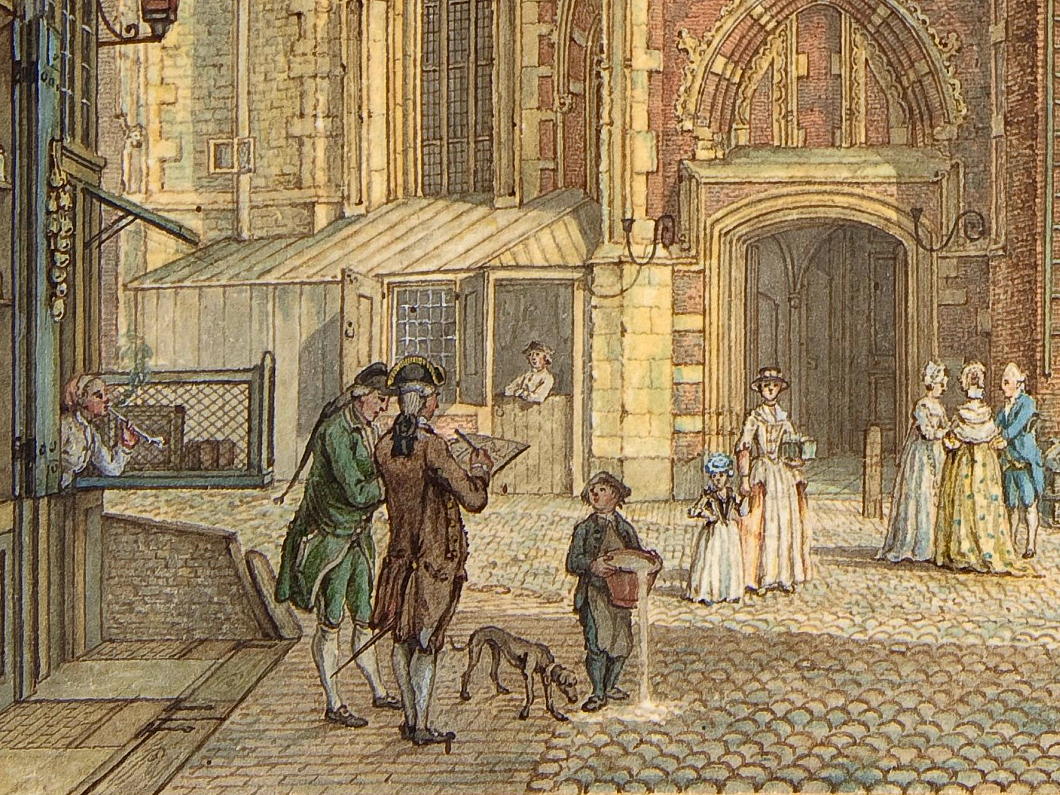

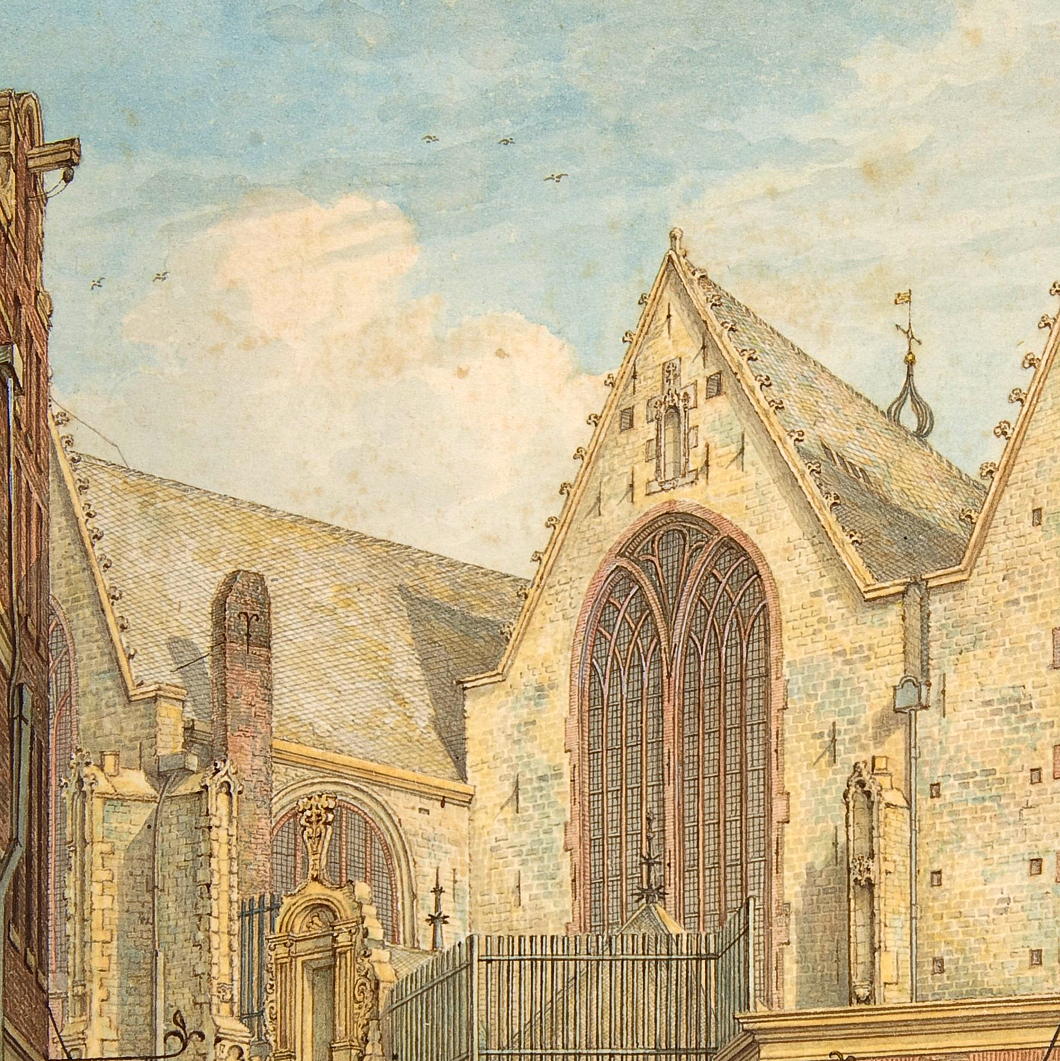

Way out on the South Fork of Long Island, the old whaling village of Sag Harbor has the perfect little small-town American movie theatre.

There is something just right about this cinema on the village’s Main Street — as Variety put it: “beloved for not only its obscure programming but also its 1930s red neon sign with the village name”.

The single-screen cinema first graced the main drag of the village in 1936, the creation of architect John Eberson whose ‘atmospheric’ movie theatres are dotted across the United States and even as far as Australia.

Eberson designed two of greater New York’s five Loews ‘Wonder Theatres’: the Loew’s Paradise on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx neighbourhood of Fordham and the Loew’s Valencia in Jamaica, Queens.

This cinema was purchased by Gerard Mallow in 1978 who for nearly four decades preserved the Sag Harbor Cinema as an arthouse movie theatre with an eclectic offering.

In December 2016, the cinema suffered a devastating early morning fire that destroyed most of the structure.

The iconic neon signage was salvaged by Chris Denon of North Fork Moving and Storage and the sculptor and ironworker John Battle.

Meanwhile, a community partnership that was already in discussions to purchase the institution from Mr Mallow came together to raise funds and oversee the rebuilding, including several improvements.

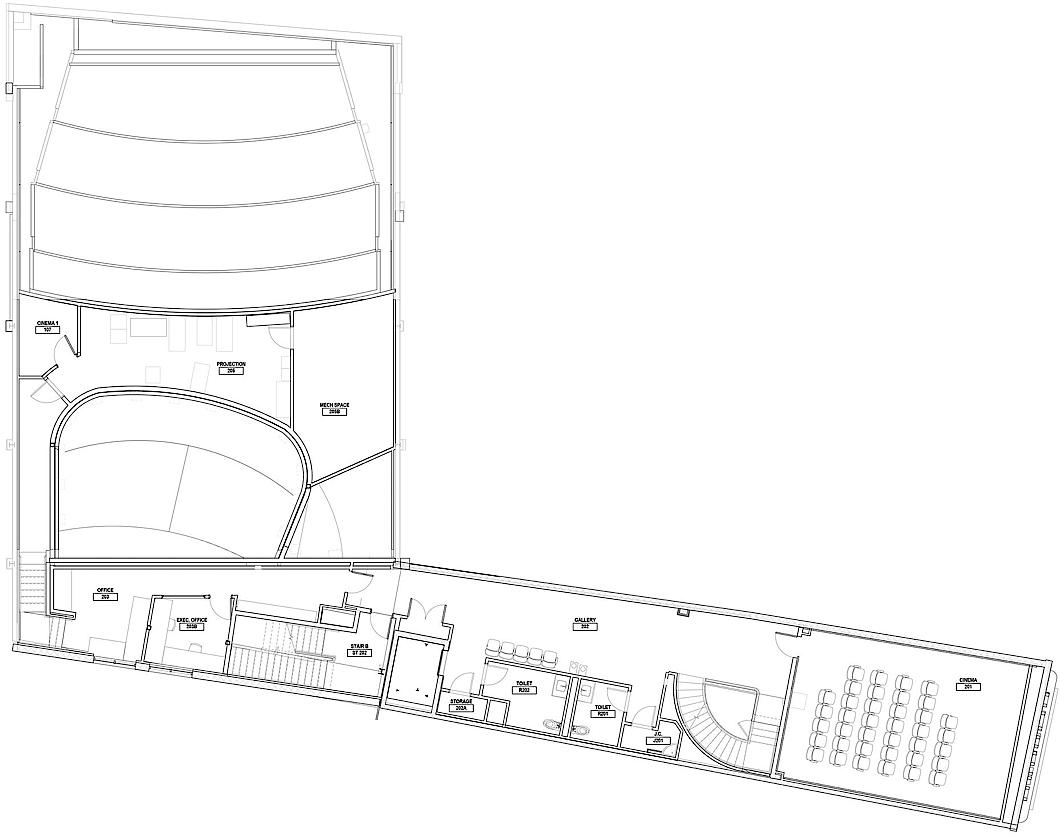

The main hall was divided between a large screening hall and a smaller one, along with a new screening room on the first floor (that’s second in American English) behind the iconic façade.

The artist Carl Bretzke captured Sag Harbor’s cinema in plein-air painted form.

Encouraged by the Grenning Gallery, Bretzke offered limited-edition prints of his painting, the proceeds of which helped to pay for reconstructing the movie theatre.

NK Architects also created a new bar and lounge, two roof terraces, an art gallery, and educational space within the original footprint of the cinema.

Following coronavirus-related delays, the new facility finally re-opened in June 2021.

Given the improvement in the facilities, it seems like the Sag Harbor Cinema’s fire was the best thing to ever happen to it.

It is reassuring to know this little movie theatre will be gracing Sag Harbor’s Main Street for many moons to come.

Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P.

I have the poet Ben Downing to thank for putting me on to the great Hungarian writer Miklos Banffy. I will always be grateful.

But the one to whom I should be even more grateful is the writer’s daughter Katalin Bánffy-Jelen who died last month, 100 years old.

She, along with Patrick Thursfield (d. 2003), translated the great Transylvanian trilogy from Hungarian into English.

There were obituaries in The Times and the Daily Telegraph.

After the war, Katalin married a US naval officer and they settled in Tangier, still then a free port under a sort of multinational administration.

I wonder if she would have known Fra’ Freddy’s father when he was British delegate to the International Legislative Assembly of Tangier.

In the Courts of the Lord

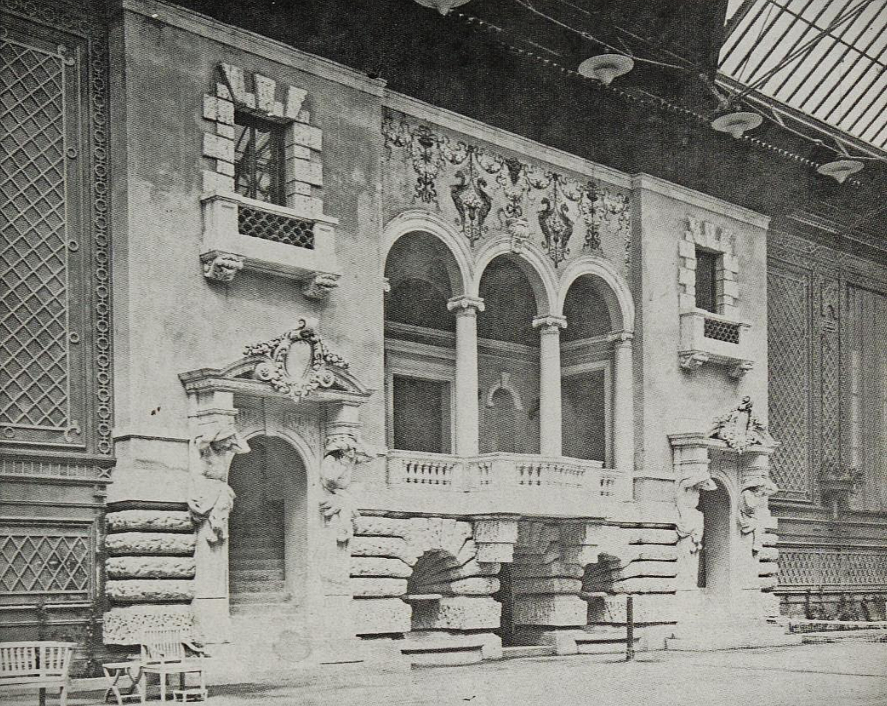

Well, not quite a lord, but a Vanderbilt — which in America is much the same. The indoor tennis courts at “Idle Hour” in Oakdale, L.I., were some of the grandest ever built in the United States.

The house itself, designed by Richard Howland Hunt for William Kissam Vanderbilt and completed in 1901, is unremarkable and not on the finer end of the spectrum. To me, it has all the glamour of a railway station serving a mid-sized town.

Just a year later, however, W.K. commissioned the architectural partnership of Warren & Wetmore — later famous for Grand Central Terminal — to design an extension that featured an indoor tennis court with adjacent guest quarters in a somewhat extravagant style.

As the polymathic Peter Pennoyer pithily put it in his The Architecture of Warren and Wetmore:

“The heavily rusticated stone of the gallery wall, exuberantly carved with atlantes and fanciful over-door sculpture and painted with scrolling frescoes, created a sculptural backdrop so surprising and original that it overwhelmed the vast open space of the court. For an ancillary building, the scale and energy of the architecture were tremendous.”

One can certainly imagine enjoying a refreshing summery gin-and-tonic on that loggia.

William Kissam Vanderbilt died in 1920. After a spell as an artists’ colony, in 1938 the estate was purchased by a cult called the Royal Fraternity of Master Metaphysicians, founded by a rogue named James Bernard Schafer who claimed he could raise an immortal child. (They also bought the old Gould stable on West 57th Street.) Schafer was jailed in 1942.

The National Dairy Research Laboratory took over the property and split the former tennis courts into lab space. Long Island’s Adelphi College bought Idle Hour in 1963 as an overflow campus which they later spun off into an independent institution, Dowling College, which shut in 2016.

For another indoor tennis court from the same period, see the old Astor place in Rhinebeck in the Hudson Valley.

American Exuberant

I have seen far too little of California, which is a shame because the confident freehand of American architecture between the wars reaches its greatest exuberance in the Golden State.

William Gayton began his eponymous Gaytonia Apartments in Long Beach, Ca., in 1929 and they were only midway complete before, as the characteristically colloquial style of Variety put it, Wall Street ‘laid an egg’ with the stock market crash.

This is a deliciously free California Gothic, unbothered by the pretensions of historicist verisimilitude. (A contrast to our still-much-appreciated academic friends on the East Coast.) Indeed, despite its castellar appearance it is mostly constructed of artfully handled stucco on wood disguising itself as stone.

And, true to the apartment house form, there’s even underground parking.

The Year in Film: 2024

I love a trip to the cinema and since 2021 we’ve had an Everyman cinema here in God’s Own Borough of Southwark, smack dab in the heart of Borough Market — a great boon for us locals.

We already have the BFI (and its IMAX) next door on the South Bank, but the comfort and quality of an Everyman is well worth the price of the ticket. (Sadly, this website is not yet sponsored by the Everyman corporation, but we are open to such possibilities.)

I thought a brief overview of most-but-not-all the films I managed to see on the big screen in anno domini 2024 was worthwhile, so here goes:

The Boys in the Boat (USA, 124 min) — Who can say no to a good old-fashioned American feel-good film? And a rowing film, at that. Excellent recreation of the 1930s and a nice beat-the-Nazis true story. (Caveat: In a brief moment, they got the name of Jesse Owens’ university wrong.)

The Holdovers (USA, 133 min) — It’s been a while since we had a decent New England boarding school film. A pupil neglected by his parents is forced to stay at school over the Christmas holiday, with an equally forced teacher resenting his presence.

Teenager Dominic Sessa is excellent in his first film role — he was allowed to audition as they were filming at his school, Deerfield — but the real star is Da’Vine Joy Randolph as the school cook.

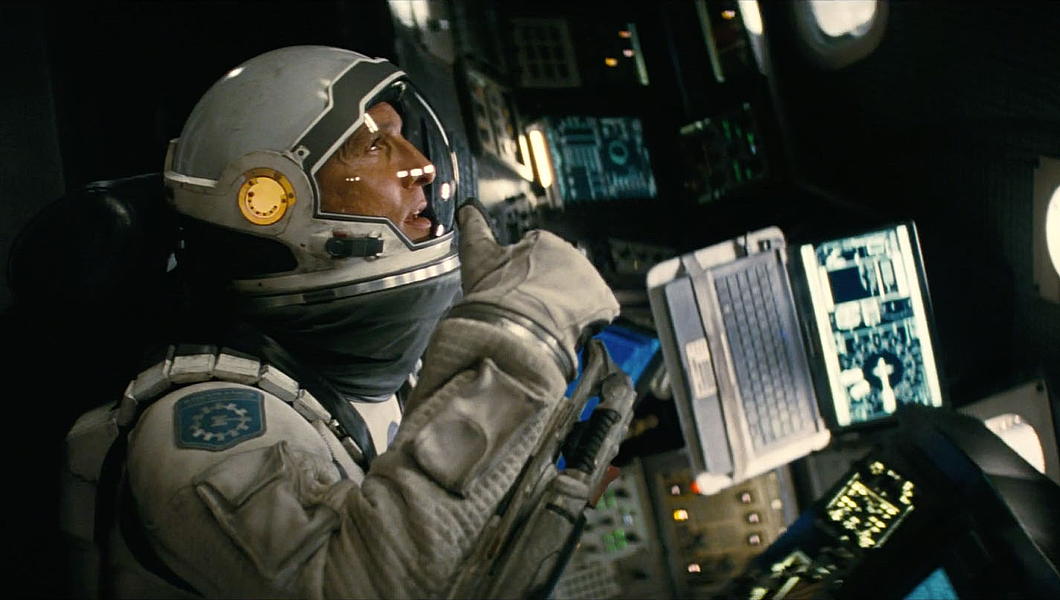

Interstellar (USA, 169 min) — This 2014 film from director Christopher Nolan is vast in its vision. BIG. An intriguing reflection on the love of a family and the fallen nature of even the bravest individuals that revives the neglected genre of cosmic dread. Ideal for IMAX which it was re-released on for its tenth anniversary. Nolan doesn’t disappoint.

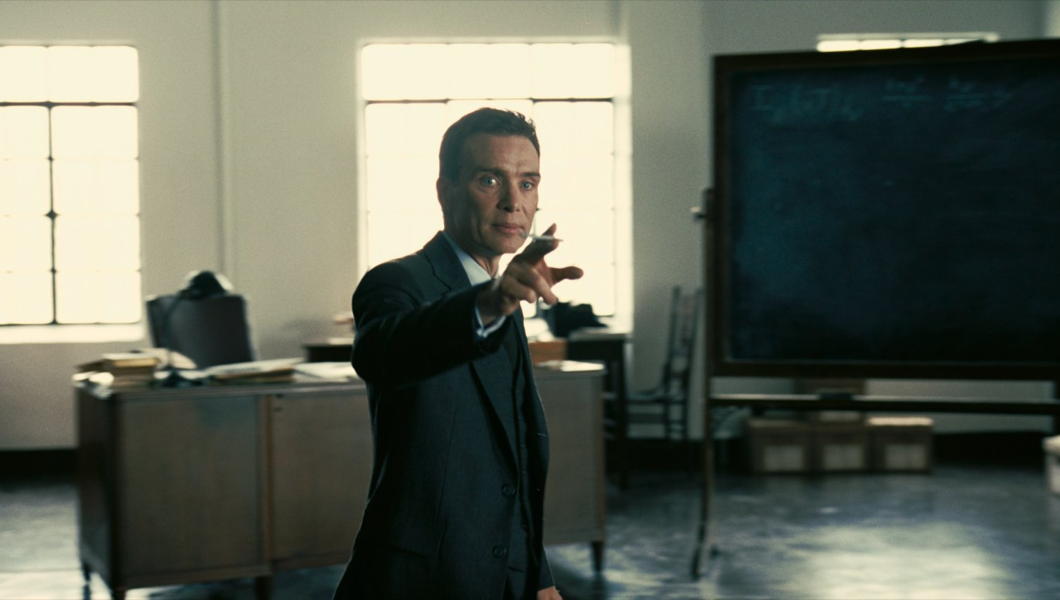

Oppenheimer (USA, 180 min) — Nor did Nolan disappoint here. This film didn’t feel nearly as long as it was, but it was beautifully captivating. I was surprised that my filmgoing companion, who has the attention span of a small child, was seeing it for her second time; I was even tempted to give it a second viewing myself (but didn’t). Top-notch film score from Ludwig Göransson, as well. ‘Oppenheimer’ was serious without being tiresome.

The Fall Guy (USA, 126 min) — A stunt double in love with his beautiful colleague is unwittingly embroiled in a conspiracy to cover up an accidental death on the set of her directorial debut.

The light-hearted framework of an incredibly charming romance nonetheless has some cracking action scenes. Anyone who’s ever been in love should enjoy this film. Emily Blunt was brilliant but Hannah Waddingham is the surprise of the show.

This one I did see twice in the cinema — a first since the film-of-the-decade ‘Top Gun: Maverick’. We need more films as delightful as this.

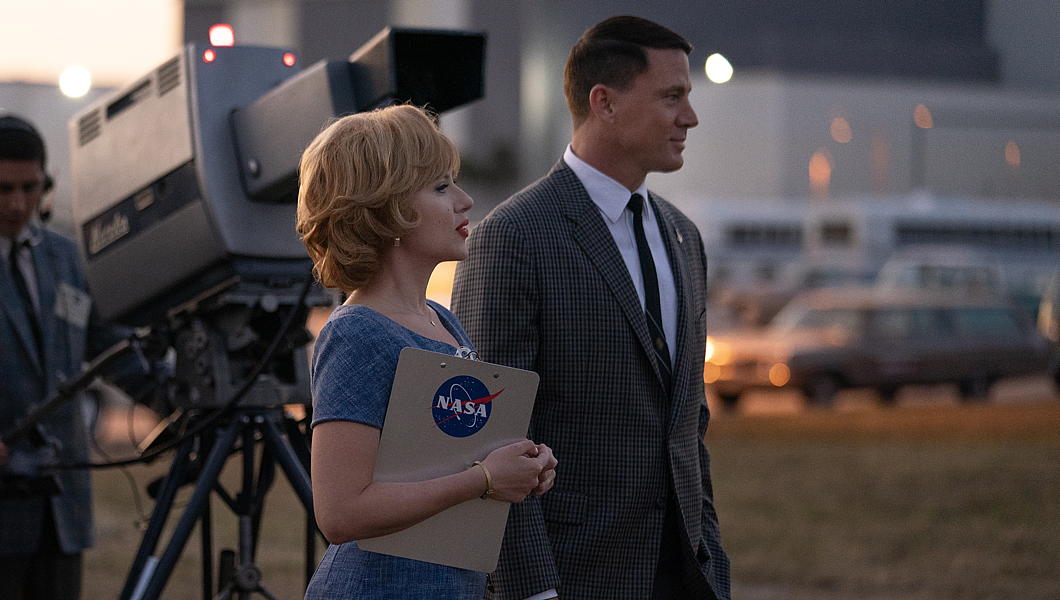

Fly Me to the Moon (USA, 132 min) — An advertising executive (Scarlett Johansson) and the NASA launch director (Channing Tatum) are forced fake the moon landings — just in case — by shadowy forces of the state (Woody Harrelson). Silly and fun.

Ne le dis à personne / Tell No One (France, 131 min) — This might be my favourite film and I probably watch it every year or so. A doctor whose wife was murdered eight years previous may finally be implicated in her murder — until a cryptic email arrives in his inbox suggesting she might still be alive. He must move heaven and earth to evade the police, find his wife, and prove his innocence.

Released in 2006, ‘Ne le dis à personne’ is the perfect blend of thriller, action, intrigue, romance, and it has Kristin Scott Thomas. What more could you want? It gratuitously adds to that with performances from François Cluzet, the amazing Jean Rochefort (RIP), Nathalie Baye, and André Dussollier.

While based on a book by Harlan Coben, the director Guillaume Canet changed the ending: the writer said the director’s conclusion was better than his. Not a perfect film — there were one or two things I would have done slightly differently — but an expertly crafted one all the same.

The Count of Monte Cristo (France, 178 min) — I’ve read the book three times and each experience has hit differently. This adaptation was watchable but flawed. The main actor lacked gravitas and it’s a tad overproduced.

The 1998 Depardieu miniseries remains the standard. Apparently we’re getting an Italian-French co-produced miniseries sometime this year but it looks disappointing, too.

Might be time to read the book again.

Ghostbusters (USA, 105 min) — What a delight this film is. Impossibly silly, deeply enjoyable, and — from the opening scenes at Columbia University and the New York Public Library — one of the most New Yorker films ever. (“Ghostbusters, whaddya want.”) It even features a cardinalatial nod of approval.

A film like this is always best in the cinema. I think ‘Ghostbusters’ may have been the first movie I ever saw in a cinema: in the movie theatre in Edgartown on Martha’s Vineyard when I was a very small boy but it was already on revival. Glad to see it again on the big screen in London.

Juror No. 2 (USA, 114 min) — Clint Eastwood is well into his 90s and still knocking it outta the park with a well-crafted film like this.

A moral thriller in which a recovering alcoholic with a newborn is called for jury duty in a murder trial and slowly begins to think he may be the one responsible for the victim’s death.

There’s a lot of layers in this film but never too much to handle. This one will get you thinking.

Point Break (USA, 122 min) — Big California vibe! Surfing, skydiving, bank-robbing, and the Feds. Kathryn Bigelow’s 1991 film became a minor cult classic and made $83.5 million on a $24 million budget. Enjoyed it.

Gladiator II (USA/UK, 148 min) — I went in with drastically low expectations but left the cinema pleasantly surprised.

Main actor Paul Mescal was a bit of a dud — tá brón orm, a chara! — but Denzel Washington stole the screen whenever he was on it. Reprises from Derek Jacobi and Connie Nielsen were strangely heartwarming, like the return of old friends.

The Twin Emperors were DEEPLY creepy and Pedro Pascal’s acting matures like a fine wine. There was even a role for our old Mossad friend Lior Raz (of ‘Fauda’) and Tim McInnerny (‘Blackadder’, etc.) played a hapless senator.

Far from the classic status its predecessor enjoys, but enjoyable all the same.

Spooks’ Crown

The Security Service, better known as “MI5” has changed its badge to incorporate the change from the St Edward’s Crown to the Tudor Crown that King Charles III has adopted.

The badge was designed by Lt-Col Rodney Dennys who himself had worked for the Security Service’s more glamorous rival, the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). Dennys had started out in the intelligence game at the Foreign Office and was posted to the Hague before the war. When the Germans rolled in he was on one of the last boats to make it to Britain.

The MI5 emblem was approved by Garter King of Arms in 1981 but (like MI6) the Security Service was still so secret that it did not officially exist, so it was added to the secret roll of arms kept under lock and key in the depth of the heralds’ college in the City of London.

In 1993, after the Service’s existence was formally acknowledged, the badge became known and a flag bearing it often flies from the top of Thames House.

GCHQ has likewise adopted the Tudor Crown, but SIS has not publicly acknowledged any official emblem. (Perhaps it has its own entry in the heralds’ secret roll?) As such, MI6 uses a government version of the royal coat of arms, but theirs has yet to swap crowns.

Jesuit Gothic

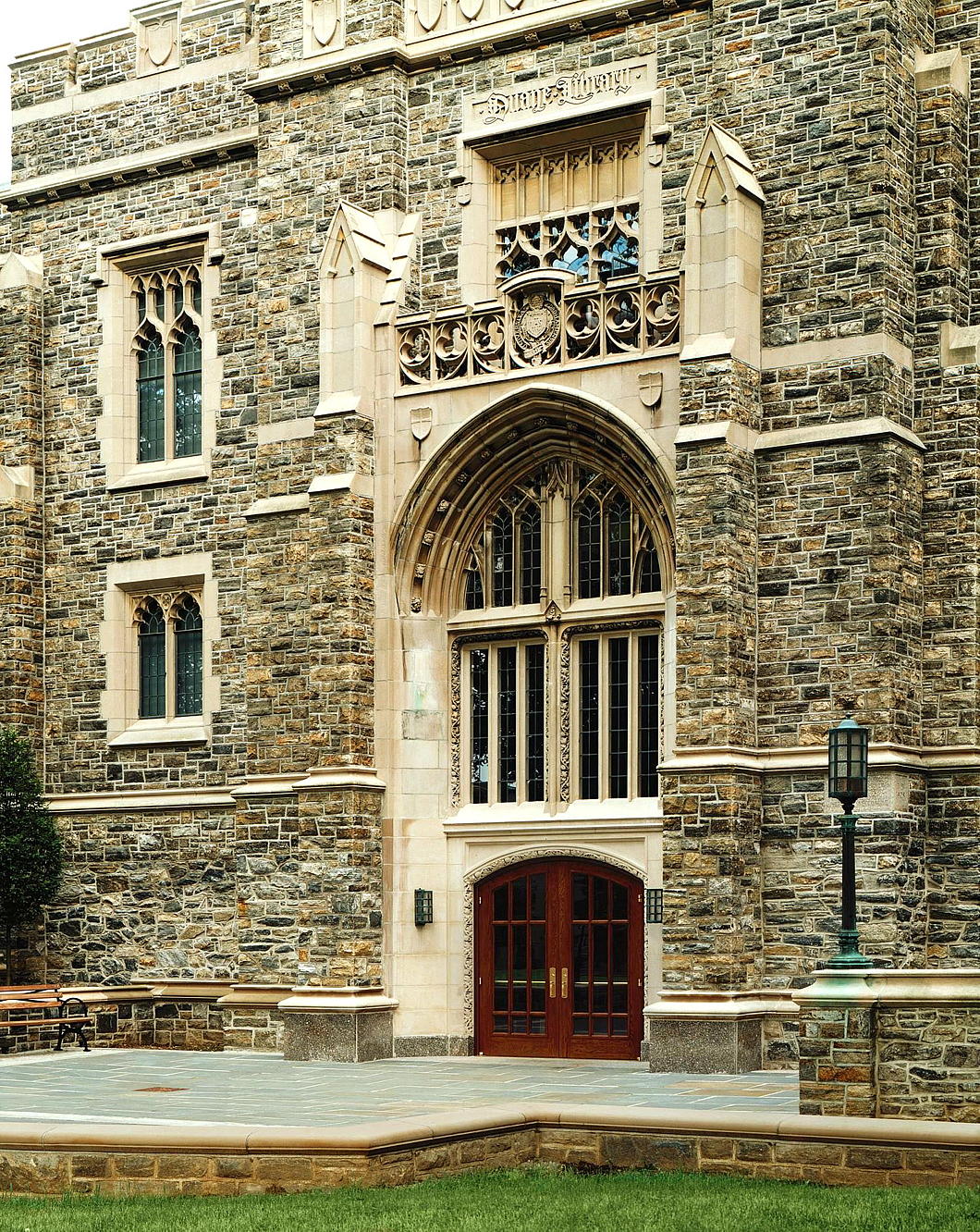

The Duane Library at New York’s Fordham University

Think of Jesuits and architecture and you probably think of the Baroque. At Fordham University, however, the SJs followed the American fashion and built in the Collegiate Gothic that gradually took hold of campuses across the continent from the middle of the nineteenth century onwards.

The first academic buildings in Anglo-America — like Harvard’s Massachusetts Hall and Yale’s Connecticut Hall — were in the vernacular Georgian style of the colonies. Robert Mills’ 1839 design for a library building at West Point was one of the first Collegiate Gothic buildings in America (and that institution’s first step on the road to going full Gothic). Some partisans will hold out for Old Kenyon as the first, others for Knox College’s Old Main. These, however, are survivors: the first Gothic university building in America was NYU’s University Hall on Washington Square, foolishly demolished in 1894.

Gothic is not solely an architectural style and it was a West Pointer, Edgar Allan Poe, who first crafted and popularised a distinctly American Gothic bailiwick in the republic of letters.

As Prof John Milbank put it the other day:

“[The] American gothic literary tradition contests the mainline American story. For the gothic perspective, the United States is a very old country: there since 1600, bearing medieval freight. Its exploring of frontiers will not open up hope, but encounter hidden horrors and horrifying potentials.”

“Far from having escaped Old Europe and started afresh and innocent, for the Gothic tradition it is rather that all the more extreme European demons (sects, cults, fears, fantasies) have fled to the New World where they always lurk, in league with its uncannily vast spaces.”

The architectural cornerstone of this Gothic chain of being linking both side of the Atlantic is St Luke’s Church in Newport, Virginia, built in the 1680s. Its pointed arches have sparked great bones of contention amongst architectural historians: is this an organic expression of a still-existing tradition from the Old World or a contrived and purposeful orchestration by colonial settlers? Gothic survival? Or Gothic revival?

I plump for the former: Gothic has always been a living tradition, even if somewhat neglected in certain generations. Ideology and architecture don’t mix well, whether it’s Pugin purporting that anything that is not Gothic is effectively pagan, or partisan modernists deriding any contemporary use of traditional forms as “pastiche”. The term “revival” is useful chronologically, but can obfuscate the breadth of an architectural, artistic, or literary style.

The brickwork tracery of Newport church renders the Gothic style in all its glories and shapes and forms an eternally valid option for the architecture of the New World. You can bauhaus all you want to, but American Gothic is real.

Thus whether unleashing ancient demons or — in the Jesuits’ case — slaying them, college presidents across the United States enthusiastically adopted the Collegiate Gothic style (while at the same time omnivorously crafting feasts of neo-classical, colonial, beaux-arts, and other styles).

Interwar American Gothic is some of the best Gothic of the twentieth century, and probably won’t be matched for centuries yet. Aside from excellent academic examples, just look at when the Gothic merges with the Art Deco as in the old GE Building by Cross & Cross at 570 Lexington Avenue.

Founded by the Jesuits in 1841, St John’s College found a home in the old manor of Fordham in the Bronx, granted to the Dutchman Jan Arcer (anglicised at John Archer) in 1671 by the provincial governor Francis Lovelace — brother to the poet Richard. Bishop John Hughes purchased the 106-acre Rose Hill estate to found a college and diocesan seminary. Eventually St John’s College took up the name of Fordham University by which it is known today.

Our old friend Edgar Allan Poe lived in a cottage in Fordham quite close by the college. He found his friends and neighbours the Jesuits “highly cultivated gentlemen and scholars, they smoked and they drank and they played cards, and they never said a word about religion”. It is claimed by some that the bell of ‘Old St John’s’, the Fordham University Church, helped inspire his famous poem ‘The Bells’.

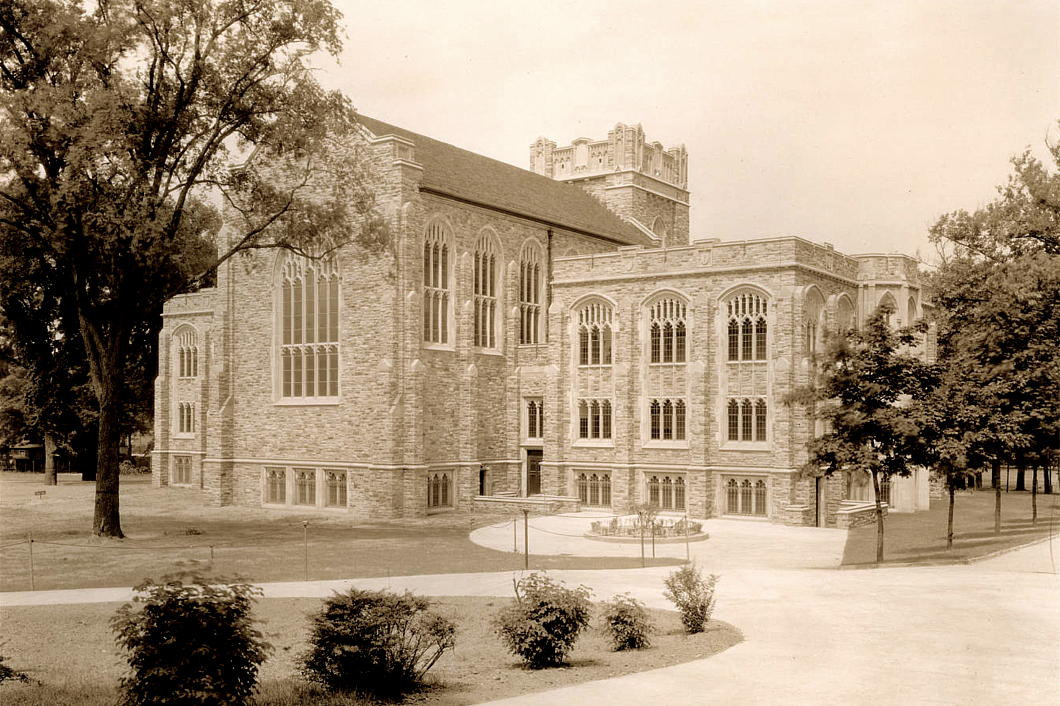

The university grew slowly until the 1920s, a decade of expansion during which president Fr William J. Duane SJ was keen to build a suitable library for the college. The library that would one day bear his name was built 1926-1928 to a design by the Philadelphia architect Emile George Perrot, accomplished in his day but not now widely remembered. (Incidentally, Perrot later completed a building — White-Gravenor Hall — at America’s first Catholic and elder Jesuit university, Georgetown.)

“Architecture,” Perrot wrote, “is the incarnation in stone of the thought and life of the civilization it represents.” If Duane Library is anything to go by, the thought and life were fine indeed.

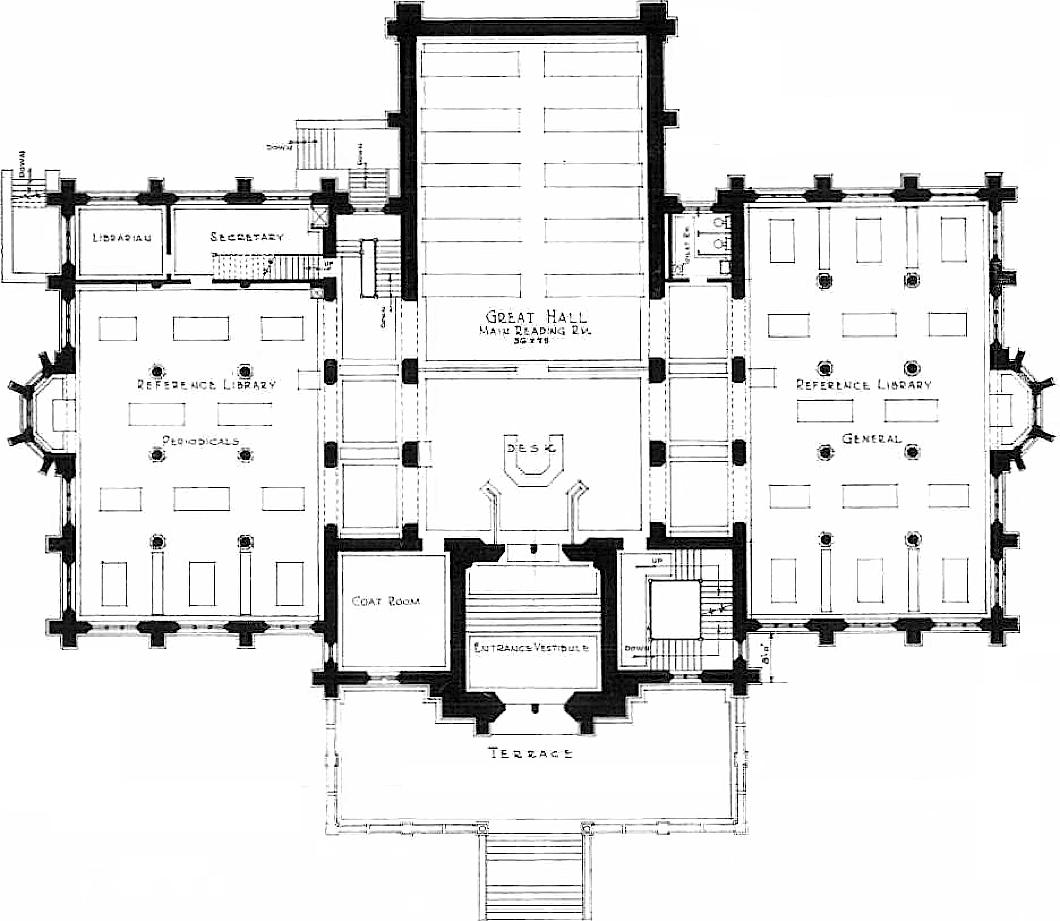

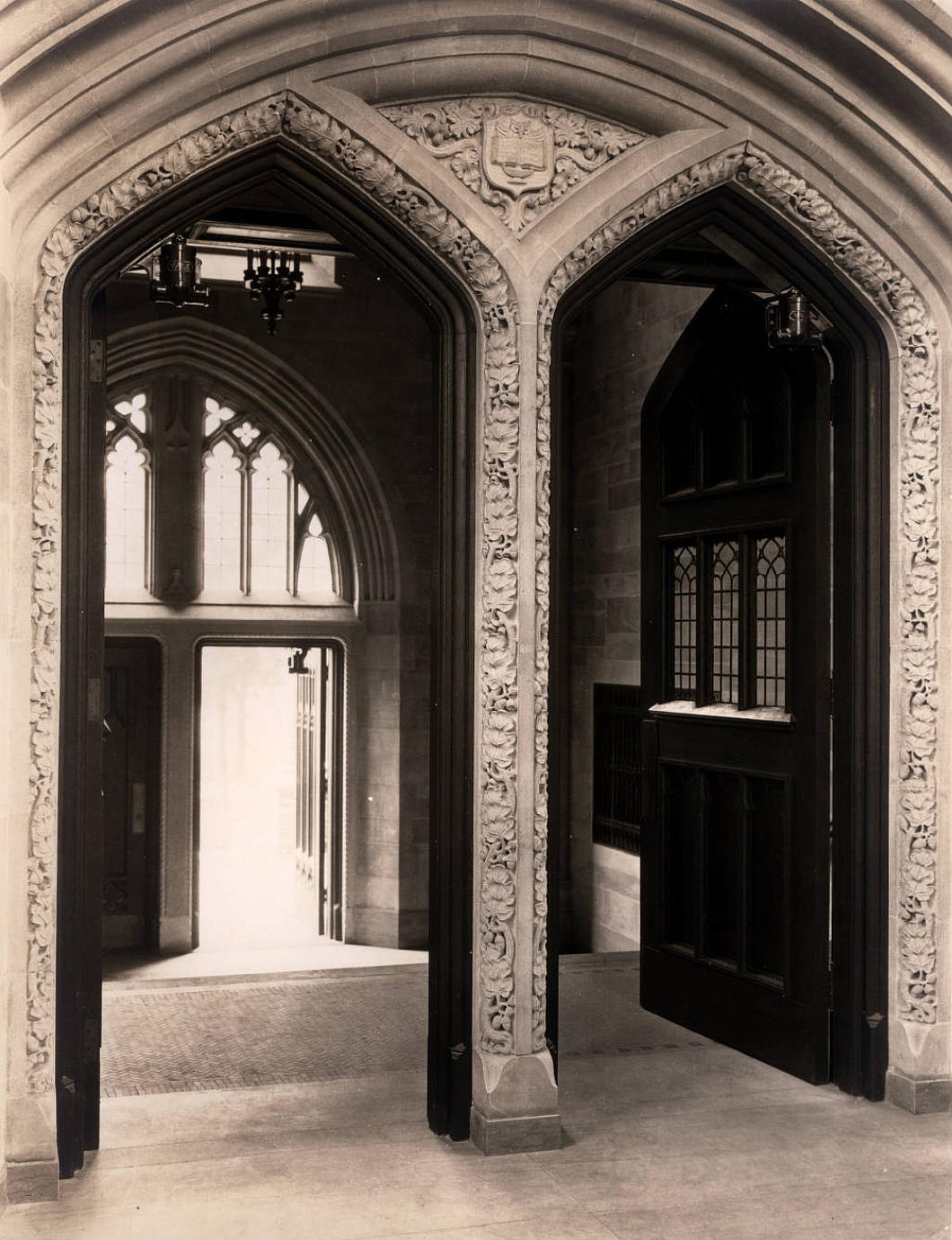

Perrot provided a central block crowned with a tower, flanked by two pavilions. In front, a wide flight of steps ascends to a raised platform and, through a pointed arch, the reader is led via the entry portal up a further set of internal stairs to the principal floor of the library.

Through these doors with their intricately carved surrounds, the reader enters the great hall of the library, passing a circulation desk — housing no-doubt assiduous and eagle-eyed librarians preserving order and quiet — and onward through a carved wooden screen to the reading area beyond.

The main reading room is a fine space, and could easily have been the dining hall of an Oxbridge college or indeed a chapel dedicated to divine worship.

The tendency of interwar American architects to design libraries like cathedrals is well documented, with Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library leading the way.

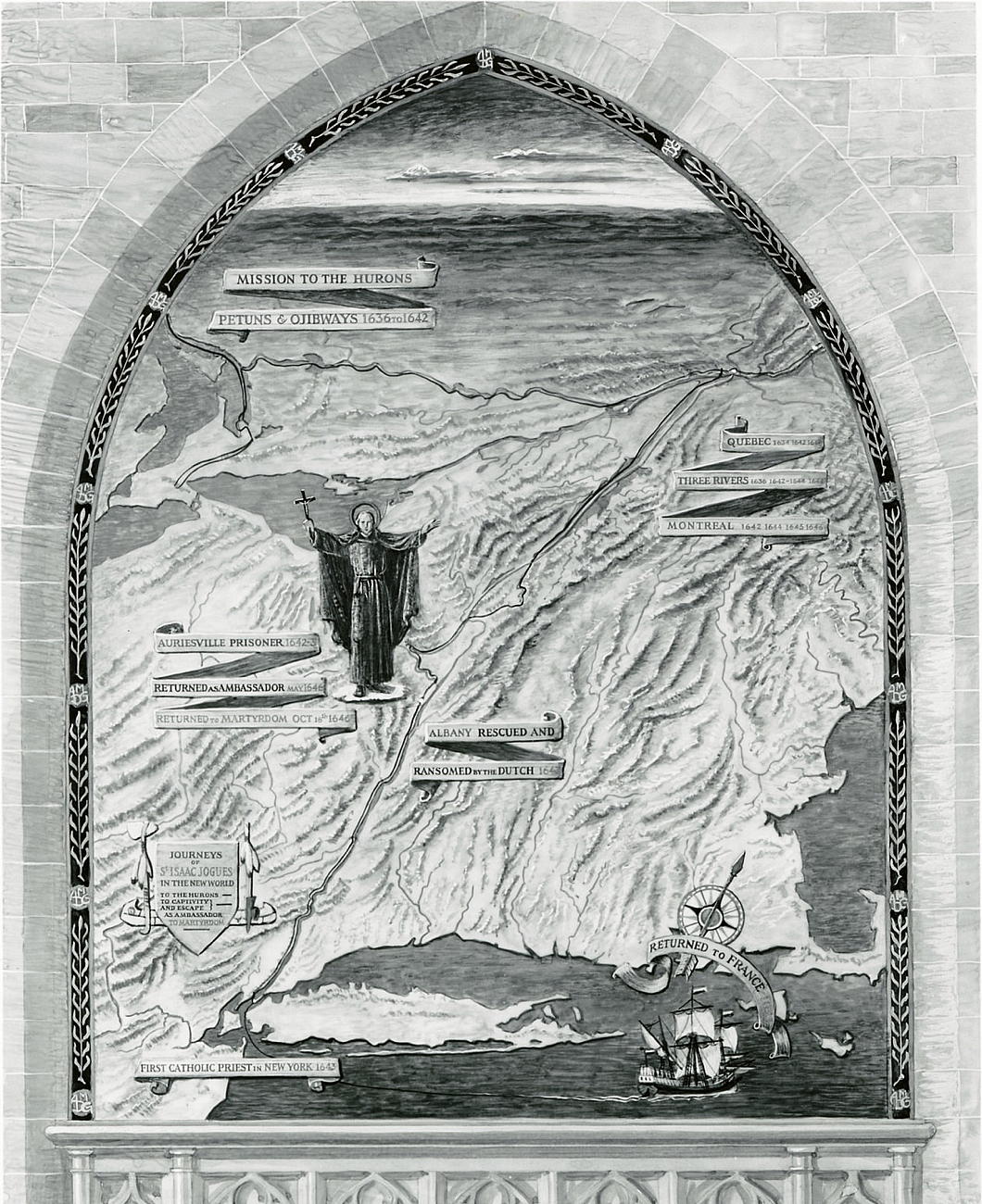

The sacral aura of the building was increased in 1949 when the mural ‘The Journeys of St Isaac Jogues in the New World’ was installed in the gothic arch of the reading room.

Jogues was the first Catholic priest to have visited the city of New York and did missionary work amongst many of the native tribes up the Hudson and beyond in New France before his martyrdom in 1646.

The muralist and designer Hildreth Meière designed this depiction of Jogues’s travels which was executed in casein and gesso relief by her collaborator Louis Ross. It was restored as part of the 2004 renovations to the building.

Circulation to the flanking wings of the library is through low arches that were frequently deployed in interwar American Gothic interior spaces, particularly in New York. (Viz. South Dutch Reformed Church [now Park Avenue Christian Church] in Manhattan, St Joseph’s Church in Bronxville, and elsewhere.)

Perrot understood the ever-evolving nature of universities as academic communities and living organisms. The future of the Duane Library was not, despite its building materials, set in stone.

The architect planned the building so it could be expanded by later generations when the need arose — either outward by extending the wings or backward by building additions to the rear.

The fathers of Fordham umm’ed and ahh’ed but never got around to extending the library. Instead they crammed more and more volumes into the original footprint, adding layers of stacks that expanded into the great hall.

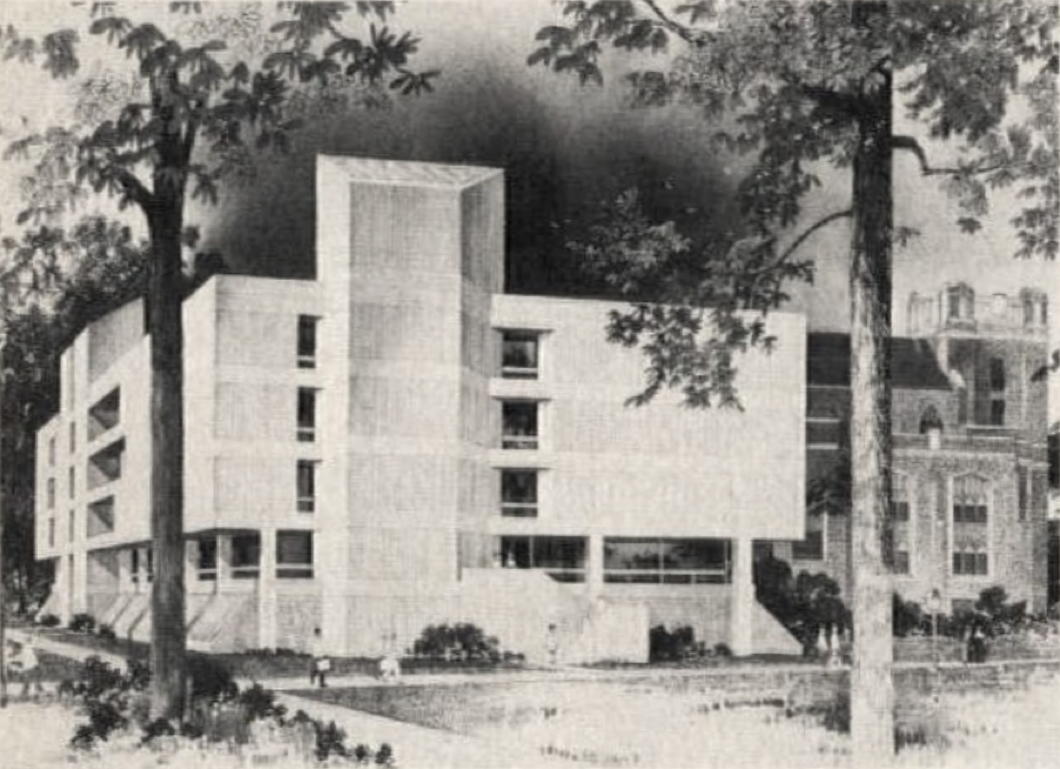

Schemes were devised, only to be shelved by economic downturns or other factors. Judging by the look of the 1968 proposal from DeYoung and Moskowitz (above), perhaps we should be glad.

In the 1990s, a massive new university library was constructed at the western corner of the campus and old Duane was left empty.

It wasn’t until 2004 that Fordham repurposed the Duane Library with a comprehensive renovation to serve as the Admissions Office and first port of call for prospective students, as well as home to the theology department.

The exterior staircase and terrace were removed and the entrance lowered to the ground level, allowing easier handicapped access but also increasing the utility of the lower level interiors.

Restored to its former glory, the great hall is now used to welcome groups of visitors as well as a 140-seat performance or lecture venue.

The stained glass window was installed in 1929 as a gift from the Class of 1915, and depicts the study of philosophy, literature, astronomy, natural history, and geography.

One of the recent additions to the Duane Library is a quarter-scale replica of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. It was created for the 2017 exhibition ‘Michaelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Desiner’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fr Joseph McShane was visiting the exhibition alongside a Fordham trustee, his wife, the Fordham chair of art history, and a museum administrator and said as soon as he walked into the room he wondered if he could find a home for it at Fordham.

As chance had it, while viewing the exhibition they bumped into Dr Carmen Bambach, a Met curator specialising in Italian Renaissance art who had previously been an assistant professor at Fordham.

Following the tour, the group decided to propose that the university house the copy of the ceiling once the exhibition was finished. “Much to my surprise,” Fr McShane said, “we were informed a few weeks later that the Met approved our proposal.”

Taking inspiration from Prof Milbank’s earlier-mentioned comments about gothic literature, we could hardly visit the ancient manor of Fordham and the former library of its Gothic university without taking in a ghost story.

On a Sunday night before a final exam, an economics student was studying late in the Duane Library and was the last person left on the floor. Suddenly he heard the sound of footsteps and peeked outside his cubicle. He saw an old priest with a kindly face so he said hello to him.

The priest introduced himself as Father John Shea and asked what he was doing in the library so late. The student explained that he had an economics exam he was studying for. “Oh!” said the priest. “I used to teach economics here. But I haven’t taught in three years.”

The priest asked if the student would carry on to do a PhD but he said no, he was planning to go to law school instead and had already heard back from Georgetown. “Good school! I got my doctorate there,” the priest offered.

After a few minutes of pleasantries, the student ended the conversation and returned to his studies.

Following the exam the next day, he was in the economics department and, chatting with the departmental secretary, he mentioned that he had met Father John Shea the night before. The secretary told him he must be joking because Father Shea had been dead two or three years.

A look in an old departmental catalogue confirmed that the good father had indeed obtained his doctorate from Georgetown and a picture of Father Shea looked like the priest the student saw.

As luck would have it, in 2012 another Fr John Shea was appointed to Fordham College at Lincoln Center, making him the third Jesuit of this moniker at Fordham since John Gilmary Shea.

As the admissions office and theology school, any ghosts still haunting the Duane Library will have plenty of new visitors to meet as well as learned scholars to discourse with.

And while Fordham may be haunted, it is good to know its ghosts are friendly rather than fearsome.

Christ Church

Christ Church

Lancaster County, Commonwealth of Virginia

Nonetheless, this gem of the American Georgian building arts — designed by an unknown hand — is an almost miraculous survival.

It was built 1732-35 by Col. Robert “King” Carter, the planter and merchant lord who served as Speaker of the House of Burgesses, President of Virginia’s Privy Council (the Governor’s Council or Council of State), and eventually Acting Governor of the Dominion.

The regal moniker by which he was known reflected the wealth and power he obtained in the colony, and Christ Church was constructed to serve Carter’s country seat at Corotoman.

The substantial mansion had burned down in 1729 but Carter carried on, living in the dower house of the estate. Such was his wealth that the fire barely featured in his diary, though he much lamented the complete loss of the wine cellar.

Christ Church had no natural parish and the loss of supporting glebe lands after the Church of England was disestablished in Virginia in 1786 removed the main source of funds to maintain the church.

It was only intermittently used during the nineteenth century, but in 1927 the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities took charge of the site and began restoring Christ Church.

In 1958 that esteemed body erected the Foundation for Historic Christ Church which has devoted its attention and resources to the care of this Georgian treasure ever since.

This work has by no means been limited to architectural preservation: the Foundation promotes scholarly research on the Carters, the world of the Virginia plantations, and every aspect thereof, in addition to operating a museum on the site to explain Christ Church to visitors and travellers.

Thanks to the efforts of Edmund Berkeley Jr (1937-2020) — who carried on the work of his uncle Francis L. Berkeley (1911-2003) on Virginia’s colonial papers — the surviving diary, correspondence, and papers of “King” Carter are now in the care of the Historic Christ Church museum.

Most importantly, God is still worshipped in some form at Christ Church: the Episcopalian congregation in Kilmarnock, Va., holds Sunday morning services here from June through September according to ‘Rite One’ of the Protestant Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer.

The church is best approached through the simple avenue of cedar trees that leads the visitor straight to Christ Church’s west door.

It looks particularly cozy in winter.

and Michael Kotrady via Wikimedia Commons (modified).

Dempsey Heiner, Art Critic

Dempsey Heiner was neither coward nor fool: he lied about his age to join the U.S. Navy during the Second World War and later studied at Harvard, Yale, and the Sorbonne. His schoolmate from St Bernard’s days, the Paris Review founder George Plimpton, described him as “the brightest boy in the class, a genius”.

In addition to his wide reading and erudition (which he wore very lightly), Dempsey was also one of the kindest, gentlest creatures the world has ever known. He spent most of his life uncomplainingly caring for his disabled wife day in and day out for decades. By the end, she was immobile, blind, and nearly comatose.

As his parish priest put it, “Not once did I ever hear him speak of her as anything but a blessing… and he seemed never so joyful as when he tried to make her drink through a straw.”

He died in 2008 and I still think it was one of the greatest privileges in my life to have counted him amongst my friends.

Dempsey’s most famous act — one would be tempted to use a bit of New York tabloid hyperbole and say most notorious act — occurred on this week in 1999. It is might best be described as the nexus between filial piety and art criticism.

In the late 1990s, Charles Saatchi put on an exhibition at the Royal Academy entitled ‘Sensation’ displaying works from his own collection produced by ‘Young British Artists’ or YBAs. The show was largely an act of self-promotion and the Royal Academy was accused of collaborating with Saatchi to increase the value of his own collection for eventual re-sale.

Among the works on display was a depiction of the Blessed Virgin which was surrounded by pictures cut out of pornographic magazines, although the press tended to centre in on the artist’s use of cow dung in the painting.

By 1999, Saatchi’s exhibition had crossed the Atlantic where it found a temporary home at the Brooklyn Museum. Despite being one of the best collections of art in the United States, the Brooklyn Museum has suffered somewhat from its borough’s perception as something of a bag-carrier for the more glamorous neighbouring isle of Manhattan.

Dempsey, a convert to Catholicism, had a profound devotion to the Blessed Virgin. He wasn’t keen on the idea of some art-market scheme profaning the image of the Mother God, so in December 1999 the 72-year-old New Yorker bought a bottle of latex paint, smuggled it into the Brooklyn Museum, and daubed the paint on the insulting artwork.

As luck would have it, the Magnum photographer Phillip Jones Griffiths was visiting the museum with his daughter and was in the room when Dempsey began his rather pro-active work of art criticism. Jones Griffiths caught Dempsey in the act with his camera and the next day the image was splayed on the front page of the New York Post.

The security guards detained him pending the arrived of New York’s finest, but Dempsey told me that once his police escort was out of view of museum officials they each patted him on the back and congratulated him for his deed.

Dempsey’s act of defiance was almost certainly a felony-level offense but, as the Museum did not want to put a value to the artwork, the Brooklyn DA’s office felt obliged to reduce the charge to a misdemeanour — still carrying the possibility of up to two years in prison.

At trial, Dempsey said the exhibition’s gravest sin was neither blasphemy nor profanation but its “suggestion that there is no beauty in the world.”

“It’s like what Jean-Paul Sartre said: ‘L’enfer, c’est les autres’,” he told the court. “I reject Sartre’s view of humanity. Art is also supposed to be about skill. There was none of that in ‘Sensation.’”

A spokeswoman for the Brooklyn Museum deployed almost comical de haut en bas at the trial: “I don’t think we’ll respond formally to Mr. Heiner, beyond pondering what in his background makes him an expert on artistic skill.” (His Yale degree was in law and his Sorbonne degree in medicine, so I’m not sure if Dempsey ever formally studied art.)

One of the museumgoers in the room at the time told the Post that, while he disagreed with the vandalism, he “understood” Dempsey’s reaction: “Someone had to stand up and say, ‘This is not right.’”

“I think it was heroic,” our own Irene Callaghan (who died this year) told the Post. “He did it for all the Christians. I’m sure if he smeared paint on the window of a fur shop everyone would think it was marvellous.”

In the end, as the Post reported, Dempsey escaped a prison sentence:

Calling it a “crime not of hate, but of love,” a Brooklyn judge slapped a $250 fine on the man who defaced a dung-daubed image of the Virgin Mary, instead of tougher penalties prosecutors sought.

State Supreme Court Justice Thomas Farber released Dennis Heiner with the fine on the condition that “so long as he has paint in his hands, he’s required to stay away from the Brooklyn Museum.”

Farber, who has called the Heiner case one of the most difficult of his career, said the frail, gentlemanly Roman Catholic advocate had taught him something new.

“I had assumed that an act like this would always be committed by an angry man motivated by hate,” Farber said. “But this was a crime committed not out of hate but out of love for the Virgin Mary.”

“When the row eventually fades,” the then-editor of Art & Auction magazine, Bruce Wolmer, wrote, “the only smile will be on the face of Charles Saatchi, a master self-promoter.”

Saatchi made a mint off the artworks he sold, sparking criticism of museum institutions’ alleged complicity in inflating the prices of YBA works.

What happened to the offensive painting? Heavily insured, it was lost unto the ages in a warehouse fire. None of the art world figures who chimed in to praise it at the time mourned its passing. Sic transit opprobrium mundi.

Dempsey himself had no regrets, but he said he wouldn’t engage in any more public acts of paint smearing.

“I’m too old,” he told the press, chuckling. “I’ve said my piece.”

May he rest in peace.

Vote AR

The lush and verdant tree formed in the shape of the Netherlands grows from deep roots spelling out ‘AR’, the name of the main Protestant party — once led by Abraham Kuyper.

As Kamps and Voerman point out in their book on posters from the Dutch Christian-democratic tradition (in print / online), this poster is a “rather complicated allegorical representation”.

The Secret Chapel of Harkness Tower

Yale’s Harkness Tower is, by my estimate, the finest tower in the United States and its designer, James Gamble Rogers, one of the best American architects of his day. JGR is in the Pantheon of his craft, though not quite as highly appreciated as Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue or Ralph Adams Cram.

Harkness Tower is a monument to verticality: from the ground up at each and every stage you expect it could end right there in completeness and beauty — but then it goes another stage higher. Rogers was inspired by the “Boston Stump” of St Botolph’s Church in Lincolnshire but he took that form and creatively expanded and elaborated upon it.

The tower rises 216 feet — one foot for every year Yale existed by the time of its construction.

Yalies – “Elis” – are inveterate founders of drinking clubs which, in order to cultivate a deliberate air of inscrutable mystery, they call “secret societies”, even though many of them are (thankfully) nothing which might rightly be called such.

It was years ago on one of my occasional stays in New Haven for some convivial merriment organised by just such a cabal that my old friend A.B. and I were passing Harkness Tower and I was expounding upon its beauty.

“You know, of course,” A.B. alleged, “it has a secret chapel in it.” I had no such knowledge, and pressed for more information. “Well it’s not quite a chapel, but it feels like one. The university almost never lets anyone use it.”

Universities never do. Once a university has anything, they do their best to stop people using it. (Anyone at Edinburgh University: just try throwing an event in the Raeburn Room in Old College and find out.) (more…)

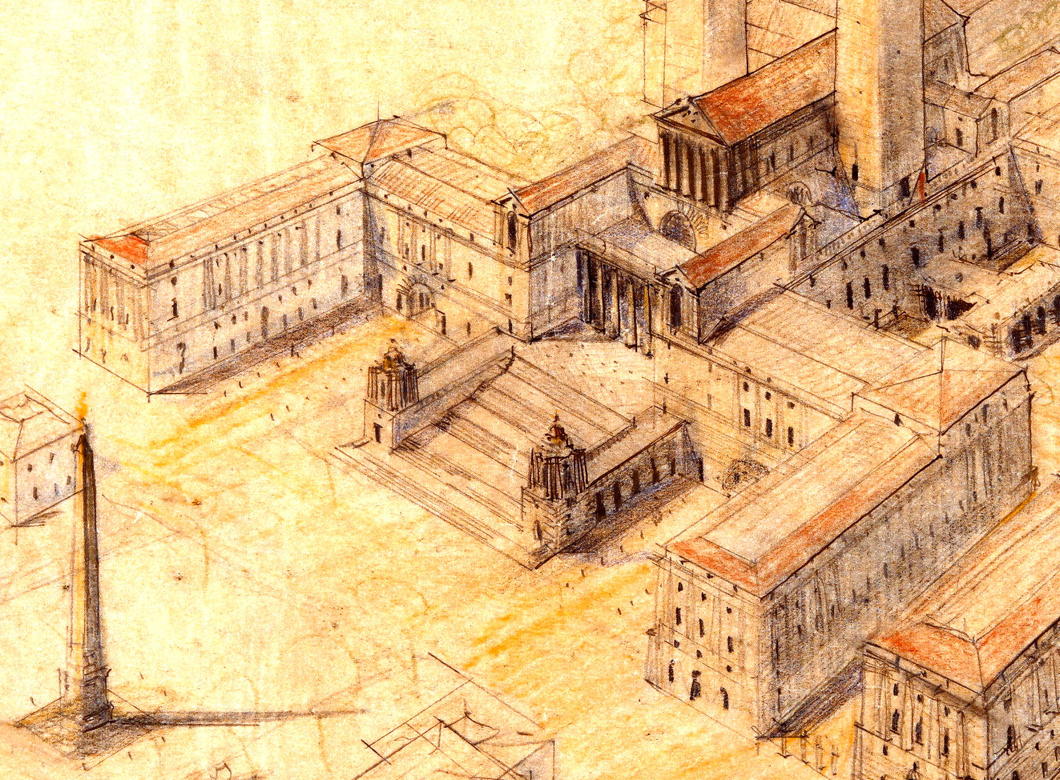

London’s Unbuilt University

The Bloomsbury Scheme of Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens

The University of London is a curious institution that these days no one really knows quite what to do with. At its zenith it was an imperial giant, validating the degrees of institutions from Gower Street to the very ends of the earth.

University College was founded — as “London University” — by the rationalist faction in 1826, prompting the supporters of the Anglican church to establish King’s College with royal approval in 1829.

Neither institution had the right to grant degrees, which led to the overarching University of London being created in 1836 with the power to grant degrees to the students of both colleges — and the further colleges and schools that would be founded later or come within its remit.

The University was run from the Imperial Institute in South Kensington but soon outgrew its quarters within that complex. The 1911 Royal Commission on University Education concluded that the University of London “should have for its headquarters permanent buildings appropriate in design to its dignity and importance, adequate in extent and specially constructed for its purpose”. But where?

Lord Haldane, the commission’s chairman, preferred Bloomsbury. University College was already there, as was the British Museum, and the Dukes of Bedford as the local landowners were happy to provide sufficient space to build a proper centre for the institution.

Charles Fitzroy Doll, the Duke’s own surveyor, designed a rather heavy classical scheme for academic buildings on the site north of the Museum but no progress was made before the Great War erupted.

Simon Verity: An Englishman in New York

An Englishman in New York

Not many people can claim with any accuracy to have crafted a Portal to Paradise, but Simon Verity was one. The master carver was born and raised in Buckinghamshire but made a significant contribution to the stones of New York.

At the Protestant Cathedral of St John the Divine in Morningside Heights — “St John the Unfinished” to many — tools had been downed following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. When the Very Rev’d James Parks Morton became Dean in the 1980s he decided it was time to re-start work on the gothic hulk — one of the largest cathedrals in the world.

Morton commissioned the Englishman to come and become Master Mason at the New York cathedral based on his experience on the other side of the Atlantic. Verity tackled the main task of finishing the carvings on the great west portal of St John the Divine — the “Portal of Paradise” — training up a team of local youths in stonecarving to help with the job.

“Mr. Verity took the long-dead worthies of the Hebrew and Christian traditions and made them things of wonder for people in our own day,” the current Dean said following Verity’s death earlier this year.

Most memorable was his ostensible depiction of the destruction of the First Temple, which actually showed the Twin Towers and other familiar New York skyscrapers collapsing into ruin and fire.

Late in 2018 — after the collapse of the actual World Trade Center — an unknown vandal took it upon himself to smash the stone towers off the facade, but the Cathedral has since had them restored by Joseph Kincannon who carved the original depiction under Simon Verity.

Eventually the money ran out and the stonecarvers at St John’s had to down tools yet again so Verity returned to England, but he maintained close connections with New York. He was responsible for the carving and lettering in the British & Commonwealth 9/11 Memorial Garden in Hanover Square, for example.

When the trustees of the New York Public Library proposed clearing out the stacks from their glorious Bryant Park main building and moving the books to New Jersey — a truly criminal plan since, thankfully, abandoned — Verity drew a series of doodles in opposition, many depicting the iconic lions Patience and Fortitude who guard the Library’s entrance.

A few of the mentions of his death this summer are gathered here:

The Daily Telegraph — Obituary: Simon Verity

The Economist — Simon Verity Believed in Working the Medieval Way

The Guardian — Obituary: Simon Verity

Cathedral of St John the Divine — A Message from the Dean on Simon Verity

Amsterdam

Is die Amsterdamse stadsargitektuur die mees hemels in die wêreld? Winkels, huise, alles baie aangenaam. Burgerlik. (Ek moet teruggaan.)

Die Nederlanders het ’n samelewing met ’n semi-republikeinse mentaliteit maar met (amper) al die geseënde vrugte van ’n koninkryk. Beste van alle moontlike wêrelde…

Silver Jubilee

The Critic invited me to put together a few musings on the aesthetic, economic, and political impact of the JLE and the fundamentally Conservative vision that drove it. You can read it here:

■ The Half-Forgotten Promise of the Jubilee Line

Since it went up this morning, I received a kind email from Tom Newton, son of the late Sir Wilfred Newton who (as you can read in my piece) envisioned and managed the project:

You may be interested that as a family we well remember his intense frustration with the government of the time when they tried to cut back the cost of the project by reducing numbers of planned escalators across the new stations – he had to fight tooth and nail to keep the designs intact and indeed offered to resign over the matter and ultimately successfully defended the designs against cuts. He was very firm that he had no intention of building something which suffered the same capacity issues as the Victoria line resulting from similar reductions in capacity required by government during its construction. This was one of the very few times I ever saw him angry about anything.

He developed excellent relationships with railway engineers and architects whilst in Hong Kong and loved being involved in these large scale infrastructure projects – he was made an honorary member of the Royal Academy of Engineers as a result. He loved being involved in the JLE project very much. He was absolutely fascinated in how the engineers managed the risk of tunnelling across London without damaging other lines and keeping Big Ben standing.

He was asked to lead the construction of the new Hong Kong airport but decided it was time he had spent enough time in Hong Kong.

As a director of HSBC he knew Sir Norman Foster well from when he was the architect on the HSBC office building in Hong Kong. However, when he was asked by the HSBC board to oversee the building of the Canary Wharf office with Sir Norman as the architect, he was asked by the board to make sure Sir Norman was kept on a very tight leash on this build after the massive cost overruns on the Hong King building.

As regards the canopy at the JLE Canary Wharf station Dad had some robust conversations with Sir Norman about adjusting its design to make sure it would be possible to keep clean.

He always had an extraordinary ability to talk to anyone, cut through to the essentials of anything and take a very principled approach in dealing with people and problems.

Many thanks, Tom, for contributing this closer historical perspective of the Jubilee Line Extension’s construction.

Articles of Note: 11 November 2024

Caro had been a Nieman Fellow at Harvard studying urban planning and land use when he came up with the idea for the book. He thought it would take him nine months, but extensive research and over five-hundred in-person interviews meant it took eight years to complete.

Caro then started working on his study of Lyndon Baines Johnson, the first volume of which emerged in 1982 and the fifth (and final?) one he is still working on. (At the end of the fourth, LBJ had just become president.)

But where does he write? Christopher Bonanos of New York magazine finds out:

It’s an ageless space, one where it could be last week or 1950 inside, matter-of-fact and utilitarian. A couple of bookcases, a plywood work surface, corkboard with outlines tacked up, an old brass lamp, an underworked laptop for emails, a Smith-Corona typewriter. The desk chair is hard wood with no cushion. There’s a saltshaker next to the pencil cup for when Ina brings a sandwich out at midday. The desk has a big half-moon cutout, same as the one back in New York, so he can rest his weight on his forearms and ease his bad back. That arrangement was recommended by Janet Travell, the doctor who grew famous for prescribing John F. Kennedy his Boston rocker. She, with Ina, is a dedicatee of The Power Broker.

He bought the prefab shack, he says, from a place in Riverhead for $2,300, after a contractor quoted him a comically overstuffed Hamptons price to build one. “Thirty years, and it’s never leaked,” he says. This particular shed was a floor sample, bought because he wanted it delivered right away. The business’s owner demurred. “So I said the following thing, which is always the magic words with people who work: ‘I can’t lose the days.’ She gets up, sort of pads back around the corner, and I hear her calling someone … and she comes back and she says, ‘You can have it tomorrow.’”

Does he write out here every day? “Pretty much every day.” Weekends too? “Yeah.” Does he go out much while he’s on the East End? “We have two friends who live south of the highway, and I said to Ina, aside from them, I’m not going this year.” There are other writer friends nearby in Sag Harbor, and they get together, but at this age, Caro admits a little sadly, they’re thinning out. He’ll be 89 this fall.

■ George Grant is a still-underappreciated giant of political thinking in the English-speaking world. He is too little known outside his native Canada, which he sought to defend from the undue overwhelming influence of its sparkling and glamourous southern neighbour. Next year marks the sixtieth anniversary of his Lament for a Nation.

Of all people, a research fellow at Communist China’s Institute for the Marxist Study of Religion — George Dunn — has written a thoughtful introductory overview of Grant’s life and thinking: George Grant and Conservative Social Democracy in Compact.

■ Katja Hoyer mused on an overlapping theme in a recent Berliner Zeitung column which she has helpfully presented in English as well:

A diplomat close to the SPD recently told me that he couldn’t understand why working-class people in particular voted for the AfD. Things weren’t so bad for them, after all. I didn’t bother pointing out that rampant inflation, high energy prices and rising rents have had a hugely detrimental effect on the living standards of people with low and middle incomes because his analysis completely misses the point.

Germany’s working-class voters, Katja argues, feel forgotten by the parties founded to represent them.

■ Since the fall of the Berlin Wall — and earlier in Angledom — political conservatism has effectively been taken over by economic liberalism.

This has denied the centre-right from learning from and deploying useful experience from outside liberalism, with the wisdom of figures as varied as Benjamin Disraeli, Giorgio La Pira, Charles de Gaulle, and Thomas Playford essentially ignored or sidelined.

Kit Kowol’s new book Blue Jerusalem: British Conservatism, Winston Churchill, and the Second World War explores the visionary side of wartime Conservatism. Dr Francis Young offers his take on Tory utopias in The Critic.

■ From a similar era, Andrew Ehrhardt writes at Engelsberg Ideas on Ernest Bevin and the moral-spiritual dimension of British foreign policy.

■ Our friend Samuel Rubinstein has studied at Oxford, Leiden, and the Sorbonne — technically the oldest universities in their three respective countries (although we all know that Leuven is in fact the doyen of Netherlandish academies).

Sam offers an incredibly interesting comparison of the experiences of these three institutions in a humble essay on his Odyssean education:

I arrived in Leiden, armed with my phrase-book, with some ambitions of learning Dutch. The first blow came at the Starbucks in the train station, when the barista answered my Ik wil graag in English without hesitating. The second came the following day when I tried again, at a different café – only this time it seemed that the barista (Spanish? Italian?) didn’t know much Dutch either: even the natives were placing their orders in English. So I gave up – save one hobby, reading Huizinga in the original. I got myself an attractive coffee-table edition of Herfsttij and managed a page or so a day, strenuously piecing it together from my English, German, and smattering of Old English. I still haven’t the faintest idea how to pronounce any of it.

■ And finally, those of us who love Transylvania will enjoy Toby Guise’s summary of the Fifth Transylvanian Book Festival in The New Criterion.

Why do you read?

We were both attending one of those formal dinners that punctuate the terms of the year so, as I was going to see him anyhow, I gave in.

With his kind permission, it is reproduced here:

I truly have no idea. I’ve never stopped to think about it. It’s probably a compulsion of some kind. I’ve always been a firm believer that some things you must stop yourself every now and then and analyse and there are other things you should never question and just accept. Reading falls in the latter category.

You’re a very social person though.

So I’m told.

And you live in London – a very social place. Is it difficult to get reading in then?

Yes and no. You need to force yourself to read before bed. It’s important to always have a book on the go. If you’re in London you’ve got tube journeys or the bus or whatever as you get from A to B. You have to maximise that time. Put it to use.

That’s why all books should be available in handy paperback editions that can fit in your coat pocket. This is much easier in winter when you’ve got a coat. In summer – also an excellent reading season in many ways – I don’t like feeling encumbered. I don’t like to carry things around. So unless it’s an old Penguin size – the perfect size – that I can slip into my back pocket then I tend not to read on the go.

You’re very passionate about book design and production.

I’m very correct about book design. It is unfathomable how incredibly and completely wrong the entire publishing sector in the English-speaking world is. I know the grass is always greener, but I’ve pointed out again and again how much better it is in France and also Germany a bit. Germany for the classics they have those excellent Reclam editions – Universal-Bibliothek – that are so useful. They are dirt cheap, small size, the easiest thing in the world to purchase, read, use, carry around. Insanely practical.

In backwards Angledom meanwhile every new book comes out in clunky hardback first and you have to wait a year or sometimes longer before you can get it in a form human beings can use. Why? Okay, maybe someone likes sitting in an armchair in their “study” smoking a pipe and reading a hardback book — D. W-B in Edinburgh, I imagine. Good for them. Do you really think that’s most people? I don’t have a commute – I have a fifteen-minute walk to work – but who wants to lug a massive hardcover on a train or a tube? Ridiculous.

But you’ve…

Another thing! It’s also perfect proof of the lies that the liberal capitalists would have us believe. They contend that if there’s a market for something it will just magically appear and the need will be fulfilled. Balderdash of the highest order. Culture exists. And publishing culture in the English-speaking world ordains you must publish the clunky cumbersome version first and then wait to issue a paperback version. Oh and when the paperback edition comes out it’s also too big in size. If ever I wield supreme dictatorial power you better believe I’d be forcing a return to the old Penguin size. Penguin don’t even use it anymore. Idiots.

But you’ve said you don’t read living writers so I guess you’re not buying newly published books anyway.

Okay, yes, maybe. Everyone knows to be a writer worth reading you’ve got to be dead. Turns out this isn’t exactly true. There are actually a good number writers scribbling away today who are perfectly worth reading, even if maybe they’re not high literature and they won’t end up in the Pantheon. Middle-brow – even popular novels – can be extremely enjoyable and worthwhile. They use up a different part of your brain. But they can be exceedingly clever. Just look at detective fiction. Agatha Christie. Insane talent, deployed in a very specific fashion. Not Shakespeare, not Racine…

Racine was a dramaturge, not a novelist.

Ooooh! Look at you! “Dramaturge”. You mean a playwright, a dramatist. “Dramaturge.” I mean really… Racine was a writer, tout court. You know what I mean. Incidentally I bought some French drama recently. Molière.

You’ve been involved in some French drama recently.

In a manner of speaking… [Several sentences of this interview redacted from public display to protect the guilty.]

…But I’ve got Molière on my pile for this winter.

Do you read a lot of French writers?

Hmm… No… Maybe? No, I don’t think so. I try and keep abreast of things. I probably read more Arabs at the moment. Right now I’m in the middle of Amara Lakhous: Clash of Civilizations Over an Elevator in Pizza Vittorio. So far it’s very clever, very human. But Lakhous is an Arab in Europe. Or is he in New York now these days? But he was in Italy for years and writes in Italian sometimes and in Arabic.

Majdalani. Charif Majdalani: he’s a proper Arab writer. Lives in Beirut.

He used to work in France though.

Okay, okay, yes. But he’s a proper Lebanese writer, alive too. I think he’s teaching at Saint-Joseph. I have him on my pile at home but I haven’t read him yet.

A little lighter – well, not in subject matter – but I’d like to read Yasmina Khadra, the pseudonym of the Algerian detective writer Moulessehoul.

Khadra lives in France, too.

Okay! Yes! I get it! Maybe you’d live in France too if you were an ex-army officer who criticised Bouteflika. Anyhow. His police novels, they’re Algiers. Gritty. I need to read them.

Lakhous is clever though – I hope not too clever. A little whimsical. It’s the world of the non-European in Europe. Chika Unigwe writing the experience of Nigerians abroad. Her writing has a very basic primalness to it.

But the non-Euro experience of Europe: Maybe there’s not enough of that – or maybe there is but it’s done by crap writers who are praised just for their backgrounds. Turns out there’s no need because there are actually good writers doing things.

But there’s plenty of rubbish. In general.

Oh ho ho – so much rubbish. But you can just ignore that. Never get distracted by it. Life’s too short.

You’ve often said that people need to curate their attention span.

Yes! Yes! A thousand times yes! There’s so much beauty in the world, whether in real life or in art and writing and plays and everything. You will be so much better off if you just ignore the crap. It’s not worth your attention. It sure as hell ain’t worth mine.

Who else of the Arabs?

Alaa al Aswany – is he any good?

I haven’t read him. You live in London: how do you keep up with Arab writers?

Oh you just do, somehow. Via French for one thing. Keep your eyes on Le Figaro littéraire. They’re in there a lot and then you have to see if they’ve been translated into English. Often you find the author but not the latest as they’re either written in French or translated into it pretty quickly. But you hear about a writer and you see what’s been translated into English. And obviously L’Orient littéraire is superb for trying to get to know the ecosystem of Arab writers. And Arablit Quarterly.

Do you read novels in French?

No – my French is actually terrible. I’m good at reading things like newspapers and non-fiction in French. Probably misunderstanding half of it, but good enough. I cannot read fiction in French, not good enough. Or maybe I just don’t try.

At a sort-of conference the other day, Adrian Pabst — what a gent he is — he introduced me to some visitors as a “fellow francophone”. Generous — I had to correct him. Anyhow, I need to learn French better. Tout le monde civilisé parle, lit et pense en français.

Est-ce que tu es civilisé ?

Ah! Nous – les celtes, les anglais, whatever – on est un peu des barbares. But the light of civilisation has fallen upon us as well. Celts in particular – I think we like to do things with words. We can deploy them in amazing subterfuges.

And then there’s Stoppard.

Stoppard: the nexus of Jewry, Mitteleuropa, and the English language.

Precisement. I know he’s a show-off. Everyone always says he’s a show-off. But come on, he’s amazing.

By the way, this is my first year where I will have in one calendar year seen three different Stoppard productions. ‘The Real Thing’ at the Old Vic – that was brilliant, just ended – and earlier ‘Rock ’n’ Roll’ at the Hampstead Theatre. Nathaniel Parker, excellent on stage.

I love going to the Hampstead Theatre because the congregation is very Jewish and it makes me feel at home.

New York.

Exactly. And then next month there’s something at… well I don’t know which theatre. Or which play.

The Invention of Love?

Yes! The Invention of Love.

That’s also the Hampstead Theatre.

Perfect. I think the first Stoppard I saw was there. They’re into him. I think he’s into them, too.

What about history though? What history are you reading?

You know, the American colonial period and the early republic have produced so much historical writing. A lot of it is very good. Okay, a lot of it is crap, too. There’s far too much pious nonsense – all that Founding Father worship, it’s excessively tiresome. Jefferson? Nein danke! Did you see they took the statue of Jefferson out of [New York’s] City Hall? Yeah they did it for the wrong reasons but – why was he there to begin with?

He’s Virginian.

He’s Virginian! And not one of the good ones! But there are so many interesting characters and amazingly accomplished people. I find George Washington boring but there are so many fascinating people from this time. You just have to avoid the pious stuff that a certain kind of respectable established American writer type can write about them.

There’s that wonderful institute at William & Mary.

I thought you were anti-Virginian.

I’m pro William & Mary. The college, that is – definitely not the monarchs. Anyhow, they have this institute for early American history and it publishes excellent historical stuff. Has done for decades. They have a quarterly journal.

Favourite Virginian writer?

Poe. Am I allowed to say Poe? Was he a Marylander?

He was born in Boston.

We won’t hold that against him. Baltimore claims him. No one associates him with Boston. I think his formative years were in Virginia. He was kicked out of West Point. And we also have Poe Cottage in New York.

Is Poe a good writer for Hallowe’en?

Oh of course. Reading is very seasonal, isn’t it? I only got into that horror stuff – what do you call it? Gothic, I guess. I only started enjoying that a few years ago. We read Poe at school, of course. But a few years ago, one winter’s evening — I was at a dinner at Boodle’s and sitting next to a princess…

Finally, the name dropping. I was warned it would come.

Just for that I won’t say which. Well she started going on about M.R. James and how brilliant he was and his stories and the settings and everything, so I got into M.R. James. And I read all his short stories. Or maybe they were just the Penguin selected ones? Anyhow, I told this to my friend – my best friend, in fact – and he said he’d recommended M.R. James to me years ago and I did nothing about it. Oh well. Sometimes you need someone to tell you things in the right setting, the soft candlelight, the gentle murmur of a table full of people in a hall… Robertson Davies! His ghost stories as well. He was made head of Massey College at Toronto — basically the All Souls of Toronto — and would write a new ghost story every year to be read aloud after some annual dinner in hall.

Speaking of which, I believe we’re being called in to dinner.

Procedamus.

Thank you.

Thank you.

India

This wartime map of India can be found in the archives of the American Geographical Society.

The AGS is a body of geographers proper founded in 1851, as opposed to the better-known National Geographic Society (f. 1888) which exists to “increase and diffuse” geographic knowledge.

The American Geographical Society and its capacious archive — at one point believed to be the largest map collection in the world — formerly lived at Audubon Terrace in New York. Since 1978 its map collection has been housed on the campus of the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee, while the Society’s offices are in Midtown.

Waarburg

Hawksmoor House, Matjieskuil Farm, Wes-Kaap

Sometimes the perfect house meets the perfect owner: if so, then Hawksmoor House and its current owners, Mark Borrie and Simon Olding, have been an ideal match. The old manor house of Waarburg probably dates from the mid-eighteenth century and, after falling victim to neglect and unsympathetic updates, has been meticulously restored in the twenty-first century.

The history of this property, with its various names and numerous owners, now spans three centuries. In 1701, the Dutch governor of the Cape, Willem Adriaan van der Stel, granted sixty morgen of land at Joostenburg in the district of Stellenbosch to the dominee Hercules van Loon.

He was the predikant of the Reformed congregation in the “City of Oaks”, where he lived in a house on Dorpstraat just a few doors down from my former abode.

Occupied in town, van Loon also purchased farmland in the surrounding district, naming one Hercules Pilaar and another Waarburg, after the German castle of Lutheran lore.

The earliest surviving map of the property shows that there was a house here by 1704, but it is believed it was rarely used by the preacher who was occupied with his duties in town.

One day in that same year, Ds. van Loon rode from Hercules Pilaar towards Stellenbosch and, in a field outside the town, cut his own throat with a penknife. His flock were astonished and recorded that no-one knew why the preacher had killed himself.

Matilda Burden has argued that the existing house was built between 1758 and 1765 by the then-owner Jacobus Christiaan Faure. By 1826, Waarburg became known as Matjeskuil or Matjieskuil which it retained for most of its existence.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories