About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The Saints are Glad

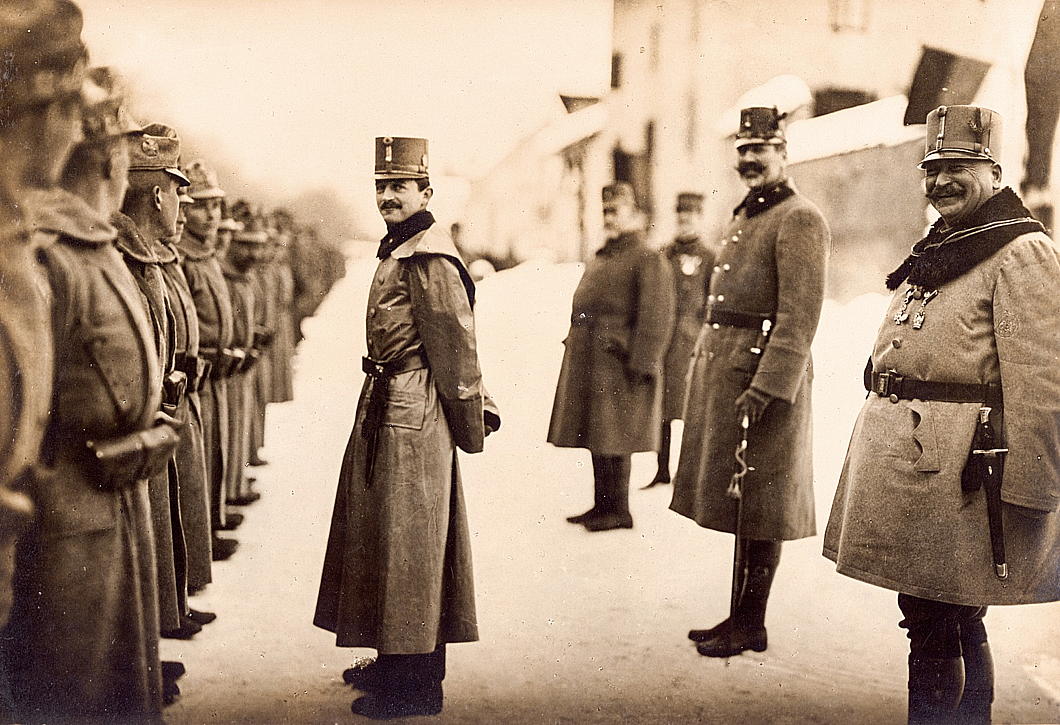

I love this photo of Blessed Charles — here still the heir to the throne — inspecting Austro-Hungarian troops in the Südtirol in 1916.

On the far right of the photograph, Gen. Franz (Ferenc) Rohr von Denta, commander of the Royal Hungarian Army, beams with a massive grin. He looks like a bit of a character.

Next to him is Archduke Eugen, the last Hapsburg to serve as Hoch- und Deutschmeister of the Teutonic Order, which in 1929 was transformed into a priestly religious order.

Franz Joseph would die just months after this photograph was taken.

His grand-nephew and successor Charles would be the last Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary, and King of Bohemia — amongst the myriad other titles — to reign (so far).

Abbott’s Gun

Berenice Abbott took a few photographs of New York’s old Police Headquarters viewed from one of the gunsmiths across Centre Market Place.

This street behind the NYPD HQ (which fronts on to Centre Street) became the gunsmiths’ district of Manhattan — policemen being one of the best customers for many of these businesses. (Criminals being another.)

There is something almost mediæval about the giant gun hanging outside, advertising to one and all what the shop had to offer.

Frank Lava, the gunsmith photographed, shut decades ago, but the John Jovino Gun Shop was originally next door before moving around the corner into Grand Street.

Like Lava’s, Jovino’s continued the tradition of hanging a giant gun outside the shop like in Abbott’s photograph.

The John Jovino Gun Shop, founded 1911, chucked in the towel last year when “Gun King Charlie” — owner Charlie Yu — decided the rent was too damn high.

An Interview with Philippe de Gaulle

Last year, in advance of the Admiral’s ninety-ninth birthday and the fiftieth anniversary of his father’s death, Paris Match sent Caroline Pigozzi to interview Philippe de Gaulle.

What follows is an abridged and completely unofficial translation of what Admiral de Gaulle insists will be his “last interview”.

ADMIRAL PHILIPPE DE GAULLE: Everyone has appropriated their share, even the Communists. All those who refer to General de Gaulle’s policy respect his Constitution, that of the Fifth Republic…

But, over the elections, my father’s imprint has faded. Pompidou, he was not quite his ideas anymore. Giscard d´Estaing, even less so… Mitterrand, basically, had the ideas of General de Gaulle, but he could not say it.

How do you judge the current president?

Emmanuel Macron is quite right to reference himself to the General as well as to other heads of state — France comes from the depths of the ages and the centuries call for it.

However, he is too involved in parliamentary life: the president should have a little more perspective. But anyway, it’s a Gaullist talking to you! The head of state is above Parliament and the government he appointed. It’s up to them to discuss day-to-day business. He has a prime minister who has to fight every day with his ministers and with Parliament.

And it’s up to the president, of course, to give direction, to choose. It is his “job”, just like dealing with the health crisis, which cannot stand any delay.

Which annual ceremonies have marked you the most?

The parade of 14 July, a commemoration of real scale which bears witness to the victories of the Republic.

My father would have liked to have celebrated on November 1 and 2 [All Saints’ and All Souls’ days] the remembrance of all war dead, for families, but that there were no other commemorations.

Why continue indefinitely with November 11, which marks the armistice of 1918, and May 8, the victory of 1945? Leave the public holidays to which the French are so attached, and let the state stick to these two dates.

Did your father like sports?

It was very important for him, because it marked the vitality of France. In his eyes, a country that had no athletes was a country half-dead.

Did he read the press?

He watched the news every night — it interested him to see what the French saw.

And, of course, he read Paris Match every week. I’m not saying that to flatter you: your newspaper is the only one that reported on La Boisserie during his lifetime.

He also read the dailies, even [the Communist] L’Humanité, but not always Le Monde, which he called for a time L’Immonde [“the foul”].

Do you know that it was de Gaulle who founded it? We do not mention it, but it’s the truth! Just after the war, in his office in rue Saint-Dominique, he asked Pierre-Henri Teitgen, Minister of State for Information, to find a journalist with a resistance background and recognised competence. The name Hubert Beuve-Méry was put forward.

My father summoned him: “You are going to make a newspaper like Le Temps before the war, which is politically neutral and with columnists. I’ll give you the money and the paper.

The first issue didn’t mention the General; in the second they started writing against him. In fact, Beuve-Méry never stopped running a pro-Fourth Republic daily, criticizing de Gaulle…

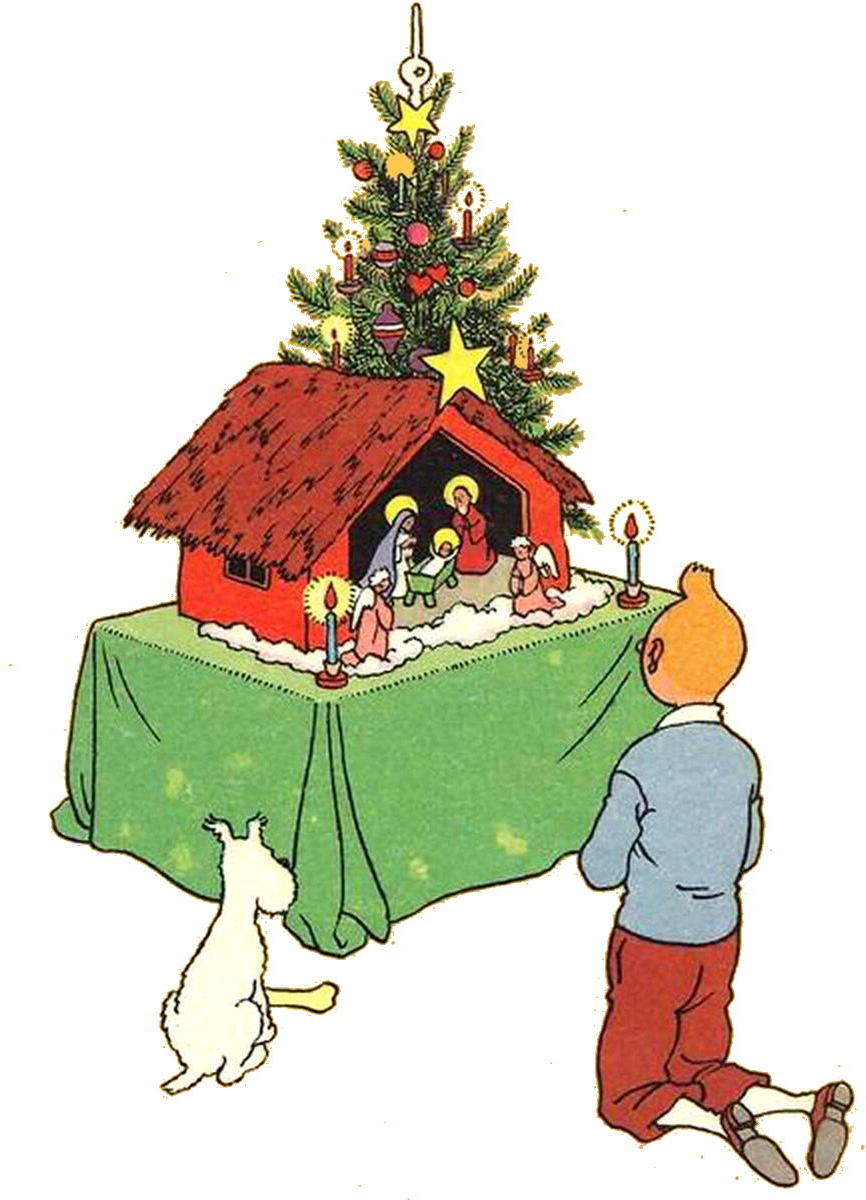

In another style, later on, my father discovered “Tintin” and “Asterix” thanks to my children, immersed in these readings during their vacations in Colombey.

Why was your mother known colloquially as “Aunt Yvonne”?

It was a nickname, as it sounded like Becassine. The truth is, people initially thought she was clumsy or frumpy. She wore her hair in a bun then, never interfering in anything.

She would go to see nuns for her charitable work, but on condition that no reporter showed up. Otherwise, she would turn right around.

You have never heard my mother speak of her charitable work, although she was devoted to it all her life! Sometimes I went with her. One day, with her, with nuns caring for hearing-impaired boys aged 4-5, the sisters played the piano for them and they put their little heads close to the keyboard. Poor people!

My mother had a knack for tackling little-known causes. She ended her life in the retirement home of the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception in Paris. There she was sure the nuns would neither speak to nor receive journalists.

Did the General use the familiar form “tu” easily?

He said “vous” to women, “tu” was more often used for regimental comrades. But he never used the familiar with men, out of a sense of honour. Not even the Companions of the Liberation! How could he have said “tu” to a soldier? People who fight, risk their lives, deserve a certain dignity. Even if they are not worthy elsewhere…

My father vouvoyer-ed my two sisters, used “tu” with my sons, but not his granddaughter. My sister and I vouvoyer-ed our mother, and she tutoyer-ed all of us.

As for my father with his wife, sometimes he was formal, sometimes he was familiar — but in public it was generally “vous”. Me, he was familiar with me and I used “tu” with him.

Your father should have made you a Companion of the Liberation.

He hesitated and said to me, “After all, you were my first companion.”

I replied: “Not the first, the second after your aide-de-camp, Geoffroy de Courcel.”

“Yes, but I cannot name you companion, because then I would have to name three times as many and I cannot do it. Everyone will know that you were one of my first companions.”

(The admiral, his voice charged with emotion, will say no more.)

The last companion of the Liberation will be buried in the crypt of Mont Valérien.

This is the rule they drew up, and the General endorsed it. They settled it a bit like the Marshals of the Empire — when the Companions were united with their first chancellor, Admiral Georges Thierry d’Argenlieu, a monk-soldier who then returned to the Carmel under the name of Father Louis de la Trinité.

After the war, they chose to commemorate the Appeal, every June 18, outside the official state — that is to say not at the Arc de Triomphe but at Mont Valérien, where more than a thousand hostages and resistance fighters had been shot. They erected a wall and a crypt, the Fighting France Memorial, and decided that the last of them would rest there.

Of the 1,038 who received the Order of Liberation, including 271 posthumously, they are now only three: Pierre Simonet, 99 years old, formerly a soldier, Daniel Cordier, centenarian, former secretary of Jean Moulin then merchant of art, and Hubert Germain, the dean of the order, also a hundred years old, who was deputy then minister under Georges Pompidou. He was supposed to join the navy with me and I found him on the “Courbet”, but he ultimately didn’t want to be a sailor anymore.

My father created the order on 16 November 1940 to reward individuals, civilian and military units, and civilian communities working to liberate France. He maintained a special bond with his Companions from all walks of life and from all political parties, even the Communist Party…

[Hubert Germain, the last Companion, died earlier this year and was buried at Mont Valérien after being recognised with full honours at Les Invalides.]

Father Euvé, the Jesuit who heads the prestigious review Etudes, explains that the Society of Jesus educates people for great destinies.

No less than two presidents under the Fifth Republic: de Gaulle and Macron!

It is clear that the Jesuits teach the meaning of the state and how to present oneself. Emmanuel Macron, a former student of La Providence in Amiens, a Jesuit institution, indeed has this talent.

Certainly he should speak a little more briefly, but he presents himself well and he is young. For me, he has not exhausted his full potential… And if he goes, who will be there? Tell me! I don’t see anyone else at the moment.

But back to the Jesuits, where my father studied. As a kid, I was in Saint-Joseph in Beirut, but it was the nuns who took care of us. Charles de Gaulle, on the other hand, attended the College of the Immaculate Conception, rue de Vaugirard, in Paris, which is now closed. His father taught there and was even its lay director after the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1901.

What a training! You should know that when a seminarian enters the Jesuits, he begins his studies again for nine years. Jesuits have a taste for the state and a sense of power. They educate people for administration, science, exploration, astronomy… So it’s important first, I stress, to know how to present yourself. Thus, the theater, rich in lessons, helps in this.

Was the General’s piety one of their legacies?

For him, life did not exist without the Creator. He could not believe in a universe that emerged out of pure chance and found the Catholic religion to be the most human, the most balanced, the one that accompanied you best until the end, and that had given rise to the most sacrifices and dedication.

The General had a deep fervour throughout his existence, with great Christian roots, marked among others by the readings of Jacques Maritain and Charles Péguy, and also by the Jesuits. It corresponded to an intimate devotion, to an interiorisation of his faith, that of a being active in the world who did not keep his baptismal certificate in his pocket.

Doesn’t France have centuries of Christianity behind it? However, in the courtyard of the Elysée, laïcité oblige: there was no waltz of cassocks.

On the other hand, remember, in 1946 it was picturesque to see, for example, Canon Kir and Abbé Pierre sitting amidst the benches of the National Assembly.

Nevertheless, men of God must be concerned with the spiritual and, in a certain way, the social.

Admiral, tell us about your second professional life.

Indeed, from September 1986 to September 2004, I was in the Senate for the RPR and then elected a UMP city councillor in Paris.

Chirac had come to get me for the municipal elections. We campaigned all over the capital and, on March 6, 1983, he snatched eighteen out of twenty arrondissements!

It was until I was 84 — the age at which my maternal grandfather died, which at the time seemed very old to me — that I was a senator for Paris. Although the cliché of the senator dozing after meals is outdated, it was no longer the navy when I was constantly running around. An admiral is a fellow who moves from boat to boat, day and night.

How did you experience the lockdown?

I haven’t been out at all but, as I’ll be 99 soon, that doesn’t really matter! It was sometimes awkward to get to the bank or run an errand as I’m now a widower on my own.

I can’t walk anymore. Taking five steps one way and five the other, your knees are rusting. Many old people are dead, masked, “emblousinés”.

My children brought me fruit but it had to be put in a bag — it was all very compartmentalised.

And how is your daily life going now?

When everything is going well, I get visits from time to time from my family — my four sons gave me six grandchildren and two great grandchildren.

I read a lot of history books; I answer a lot of the mail that mostly comes from the descendants of Free French people. I listen to classical music, I watch the big games of tennis, rugby, football on television.

And also the James Bond films, films by Melville, Louis de Funès like ‘Le Petit Baigneur’, westerns, and documentaries on animals, nature with its distant landscapes, deserts, the Far North… There are magnificent places, countries where I have not been and where I will never go: Mongolia, the Himalayas… I only did mountaineering on screen. (He laughs.)

Was the cinema one of the General’s rare “distractions”?

He liked to see films, pre-war comedians and great actors such as Charles Boyer, Fernandel, Louis de Funès… He also liked Michèle Morgan, whom he found quite jolie, with a lot of allure, acting well.

At the Elysée Palace, having little time, he mainly watched the news. This had led to some myths, such as that of an announcer who was said to have been kicked out because my mother thought it was inappropriate for her to show her knees. Completely ridiculous! My mother did not get involved in this, especially since those in the audiovisual sector were more for de Gaulle, while the print media were often against him.

Has President Macron come to visit you, a few days before this historic anniversary?

Why would he do that? Be serious: he has no time to waste! He already sees far too many people and, at almost 99 years old, you are just a vestige of yourself.

[But on this, Admiral de Gaulle’s 100th birthday, President Macron has issued a communiqué.]

A vestige with the great pride of being called de Gaulle!

I admit I found it heavy, but hey, that’s how it is. We don’t choose such things. Carrying this name hindered my own freedom, constrained me to a lot of discretion. Besides, I joined the navy so as not to be in the army, where I would have had an impossible life. The navy is looking out to sea!

Lastly: write it down that this is my last interview. I insist! I am now too old for that. And don’t tell my sons that I gave you an interview. I’ll have to tell them that it was you who caught me, “caught” me. So, thank you for the photos, the historic Paris Matches and the cake. I shouldn’t eat cake anymore… At my age, sugar isn’t very good!

Christmas 2021

A Metropolitan Christmas

I suppose Whit Stillman’s ‘Metropolitan’ is not strictly speaking a Christmas film but Yuletide is as good a time as any to watch the most Upper-East-Side movie ever to make the silver screen.

It includes a scene (clip above) from the Service of Nine Lessons and Carols at St Thomas, Fifth Avenue, which to my mind is the best carol service in New York. It’s even better when followed by a few drinks at the University Club one block up.

Know Your Counties!

A very useful resource: the Wikishire map

While we all still live in the ruins left by the Tyrant Heath when he destroyed local government in this realm, it is always re-assuring to hear of those who perpetuate the old ways of eternal England. Heath created ‘administrative counties’ on top of the traditional counties, and these new counties ran riot over ancient boundaries.

For example, Abingdon, which is the county town of Berkshire, now finds itself confusingly administered by Oxfordshire County Council. Worse, many newly arrived emigrants from London and other parts know no better and refer to Abingdon as being ‘in’ Oxfordshire rather than merely being administered by it.

Berkshire’s beautiful baroque County Hall now sits empty and unused, frozen in formaldehyde and reduced to the status of a mere museum rather than a living, breathing thing.

Contrary to the belief of some, traditional counties have never been abolished and they are even perfectly valid for postal addresses. Many, when doing their annual round of Christmas cards, prefer to include the traditional county when addressing envelopes.

If you are unsure of what county your addressee lives in, there is now a very useful resource from a website called Wikishire: a Google map of all the traditional counties in the home nations — England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales.

Simply plug in the post code or town name and it will show you the proper county in which the spot in question is located. A happy marriage of new technology and the old, undying ways!

St Birinus

Staying with friends in Oxford a few weeks ago meant that Sunday Mass was heard at the church of St Birinus in Dorchester-on-Thames.

This church was built in 1849 by the local Davey family and dedicated to the priest who converted the king and people of Wessex whose relics were venerated at Dorchester Abbey.

For more than the past quarter-century St Birinus has been restored and improved by the parish priest, Fr John Osman. Mass is offered here with great reverence, and accompanied by excellent music. They are currently raising money for a new organ.

Auspiciously the architectural historian Michael Hodges wrote an article about the church in the October 2021 Catholic Herald.

St Birinus is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful village Catholic churches in all England. It is a visual feast best experienced in the flesh.

The Most Minor of Redesigns

We’ve gone a very long time without a redesign of andrewcusack.com, and while of course all change is bad I promise this is a relatively minor redesign, befitting the eighteenth year of this our little corner of the web.

There’s still bits and bobs I’m fiddling with, but I have named the new design ‘Overberg’, after the delightul region of the Cape just over the Hottentots-Holland mountains where deserters, smugglers, pirates, and those valuing solitude first planted the seeds of settlement.

Die Overberg includes towns such as Swellendam, Caledon, Bredasdorp, and Napier, as well as the Overberg Toetsbaan where South Africa tests out its latest aeronautical and aerospace technology.

Indeed the previous design of this site (from 2016) was named ‘Kleinmond’ after one of my favourite nooks of the Overberg. If you click the picture above, or any picture that lightens when the cursor hovers over it, you can see a larger version of the image.

‘Overberg’ is a minor reordering of ‘Kleinmond’ (2016) which was largely based on was ‘Rhinelander’ (2013). This was preceded by ‘Roskilde’ (2011) and ‘Rouwkoop’ (2010) which was a minor update of ‘Elsenburg’ (2010), and before that ‘Göteborg’ (2009).

From Buda towards Pest

A 1959 view from the Vienna gate of Budapest’s Castle district

Taken in 1959, a photograph in the Fortepan archive shows two girls standing on the stone bench of the Vienna Gate — rebuilt in 1936 to mark the two-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of Buda’s liberation from the Ottomans.

Hungary’s domed neogothic Parliament Building sits in Pest on the opposite bank of the Danube in the distance, with the baroque spire of the Church of the Wounds of St Francis nearer on the Buda side of the river.

Sadly, this fine view can no longer be seen: the trees in the park below the Bastion promenade have been allowed to grow too tall. A somewhat superfluous flagpole bears the banner of Budapest’s 1st District.

The Hungarian government has invested a great deal of care and attention (not to mention investment) to the Castle quarter in recent years, so perhaps restoring this view could be added to their to-do list.

London Visitors

1874, oil on canvas, 63 x 45 in.

Happily, the Tudor-era uniforms are still in use there and are the hallmark of the school to this day.

The visiting couple are obviously in from the provinces, and the woman gazes daringly at the viewer.

I wonder if the cigar on the steps was left for a moment by the artist as he dashed to take this snapshot.

The threat to Bevis Marks

The Spanish & Portuguese synagogue at Bevis Marks in the City of London is well worth a visit. The last time my parents were in town we went for a tour given by an ebullient guide who was a big fan of Ben Disraeli and who taught us the story of the congregation and the building.

In Apollo magazine, Sharman Kadish has written a good summary of the ongoing threat to Bevis Marks from proposed overbearing office developments. (Dr Kadish also wrote a 2004 article on “The ‘Cathedral Synagogues’ of England” in Jewish Historical Studies.)

One planning application which would have almost completely cut off the synagogue’s natural light has been rejected but others loom on the horizon, one recommended for approval by the City’s planning czars.

London blog ‘Ian Visits’ visited Bevis Marks in 2019.

The synagogue is now temporarily closed to visitors for renovations but shabbat services continue to take place. Visiting information otherwise can be found on the congregation’s website.

Incidentally — given that November is the month of the dead — the name carved above the entrance of the synagogue is Kahal Kadosh Sha’ar ha-Shamayim, or ‘Holy Congregation of the Gates of Heaven’ which mirrors the Catholic cemetery where two of my grandparents are buried. (more…)

Fifth Republic Britain

An Anglo-Gaullist Reading Round-up

While I’m a big Adenauer fan there’s little doubt that de Gaulle was the greatest European statesman of the twentieth century and an historical figure of such a position will always be the subject of interest.

Both Jonathan Fenby’s 2010 book The General: Charles de Gaulle and the France He Saved and Dr Sudhir Hazareesingh’s 2012 In the Shadow of the General: Modern France and the Myth of de Gaulle received wide notice, but neither as much as Julian Jackson’s 2019 A Certain Idea of France: The Life of Charles de Gaulle.

Jackson’s work is indeed magisterial and Lord Sumption’s praise of it as “the best biography of de Gaulle in any language” is only just an exaggeration. (For a strong bibliography of works on the general, see the appendix of Charles Williams’s 1993 The Last Great Frenchman: A Life of General de Gaulle.)

Study of the life and contradictions of de Gaulle is always worthwhile, but many spy a Gaullist moment in the Tory party’s refreshingly surprising turn away from ideological liberalism towards a more pragmatic conservatism under Boris Johnson.

Painting Johnson as Britain’s first Gaullist prime minister would be a stretch, but there is certainly some crossover: nationalist, economically interventionist, focused on national sovereignty and national exceptionalism.

■ Eliot Wilson pointed out this summer that Boris has always been difficult to classify in ideological terms.

■ Speccie political editor James Forsyth wrote in The Times that Boris the Gaullist puts action over ideas. Just before the party conference Forsyth also predicted the PM’s speech would be “in line with his recent Gaullist turn”.

■ QMUL’s Nick Barlow explores the parallels between de Gaulle’s Fifth Republic and Boris’s style of government.

■ Meanwhile Aris Roussinos argues that de Gaulle was always right in vetoing British entry into the EEC, and that true-blue FBPE types should welcome Brexit as advancing the cause of European integration.

■ Dean Godson (New Statesman) says that Defence Secretary Ben Wallace is pursuing “almost Gaullist trajectory for future British policy”.

■ When asked (on GB News) where he sits on the political spectrum, national treasure Peter Hitchens expressed his surprise that the Gaullist combination of “strong defence, patriotism, a strong welfare state, and national independence” isn’t more common in British politics.

■ ‘Bagehot’, the political column in The Economist, put it that the man who rebuilt post-war France has some important lessons for Britain’s prime minister: What Boris could learn from de Gaulle.

■ The American Conservative embarrassingly illustrated a piece on Europe’s Gaullist Revival with a picture of General Kœnig. (Always check the képi — as a brigadier general, de Gaulle only had two stars!)

■ Mike Bird discerned some Anglo-Gaullism in a pile of recent newspaper headlines.

■ As long ago as 2017 — what a world away that was! — Prospect argued in a somewhat rambling piece that the Brexiteers were Britain’s new Gaullists.

■ Honourable mention: Frederick Studemann chides Churchill and dumps de Gaulle, saying Boris should model himself on Bismarck and make for a Prussian Brexit.

But, for all this, when New Labour bigwig John McTernan suggested that Boris is not a Churchill but a de Gaulle, the great Julian Jackson himself pointed out there are still great differences between the PM and le général.

All the same, I’m welcoming our Anglo-Gaullist future with open arms.

Yellowfin

Flying blind by seeing a play you have no idea about and haven’t read up on is obviously a game of chance, but accompanying two mates to see Marek Horn’s new play ‘Yellowfin’ at Southwark Playhouse last night was an unexpected and thoroughly enjoyable delight.

It might just be me, but if I had been told the play was about three U.S. senators interrogating a smuggler of illegal fish substances I would have turned off completely and missed this winner.

Set in the familiar but not-too-distant future, ‘Yellowfin’ is a slow-release capsule of a not-terribly-fussed world following an inexplicable ecological disaster that, as it happens, turns out to be perfectly manageable.

It takes long and confident strides veering towards nihilism without quite touching it but the real joy is its almost-titillating scepticism of the eco-reorganisationalism that is all the rage now.

If nothing else, ‘Yellowfin’ is a deeply subversive play.

Production Photos: Helen Maybanks

Nancy Crane masters the role of the committee chairwoman whose intelligence never quite matches her confidence. Beside her is Beruce Khan as the smug younger colleague.

Nicholas Day supplies delicious nuggets of comic relief as an elderly senator not entirely sure of his surroundings. (Parallels to the most recent U.S. Senate alum to move into the White House are tempting.)

Joshua James is the fish-smuggling object of their inquiry who breezily pops the bubble of sententious seriousness the senators attempt to bring to the matter at hand.

Good writing, well acted. Let the record show ‘Yellowfin’ is well worth it.

Production Photos: Helen Maybanks

Gut Wulfshagen

I love when a house is arranged with its farm buildings around a garth or a gaard or a hof.

At Gut Wolfshagen in Schleswig-Holstein the barns are arranged flanking a narrow pinch that gives just a hint of the manor house beyond, lending an air of baroque surprise.

This house was built by Andreas Pauli von Liliencron at the very end of the seventeenth century and was acquired by the von Qualen family in 1787.

When the last of the von Qualens here died childless in 1903 they bequeathed Gut Wulfshagen to the uxorial nephew Ludwig Graf zu Reventlow. (more…)

A Dwiggins Roundup

WE LOVE FEW things more than a talent rediscovered after decades of neglect, and in the realms of graphic design no one fits this bill better than William Addison Dwiggins (1880-1956).

This man was a type designer, calligrapher, illustrator, book designer, and commercial artist with a good eye and just the right level of whimsy.

Much of the revival of interest is thanks to Bruce Kennett and his book W. A. Dwiggins: A Life in Design which has done a great deal to spread the gospel of Dwiggins.

Here below are a series of links about the man and his work. (more…)

Northern Neogothic

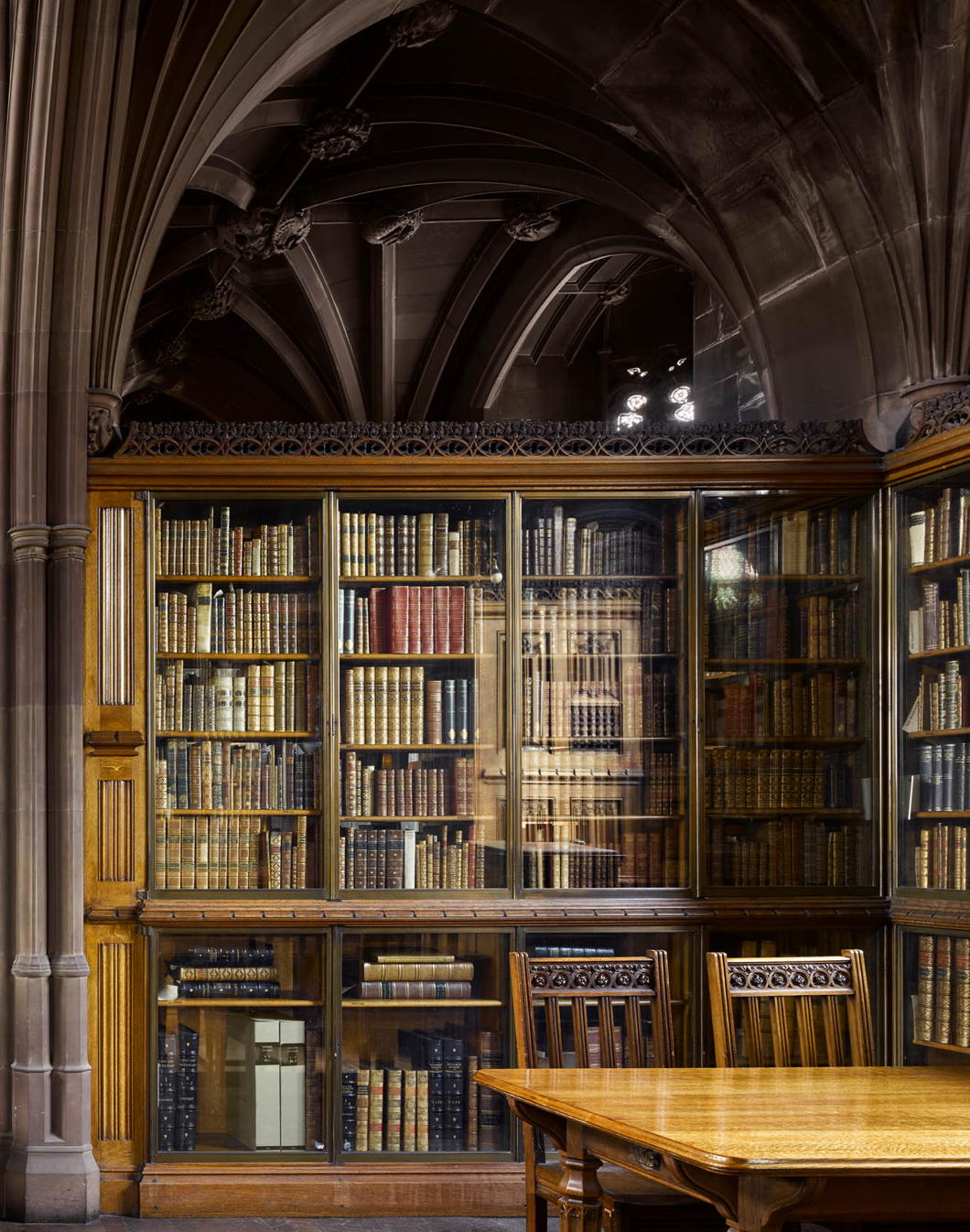

Will Pryce’s Photographs of the John Rylands Library

Will Pryce is one of the best architectural photographers out there and Country Life put him to good use for an article earlier this year about Manchester’s John Rylands Library.

The library was founded by the deliciously named Enriqueta Rylands in memory of her late husband, the merchant philanthropist John Rylands who became Manchester’s first multi-millionaire.

Manchester experienced a flowering of northern neogothicism in the nineteenth century, and the John Rylands Library is sometimes used as a film location standing in for Pugin’s Palace of Westminster, most recently in the 2017 film ‘Darkest Hour’. The city’s magnificent Town Hall fulfils this role even more often — c.f. the UK telly original of ‘House of Cards’. Scandalously, Manchester’s City Council no longer meet in their original council chamber, having decamped to the nonetheless handsome 1938 extension built next to it.

The John Rylands Library (and research institute) is here to stay though.

For more of Pryce’s work, see his website.

Quadriliteral Toponyms

A list of four-letter place names

Since the plague of psychology unleashed itself unto the world, we now know that everyone who is X is actually a “frustrated” Y. Thus the excellent schoolteacher is really “just” a frustrated actor, etc. etc. ad infinitum.

If your humble and obedient scribe is a frustrated anything, it is a frustrated toponymist. The study of place names is a fascinating realm, and one in which supposition, guesswork, and pure balderdash thrive alongside — indeed, inextricably intertwined with — genuine scholarship.

An odd idée fixe developed in my head in the past month or two — first in a Soanian apartment in the Borough, then in a café in Madrid, finally this past weekend in Wiltshire — of coming up with a list of four-letter place names (quadriliteral toponyms, if terminological exactitude is your thing).

Sunday night in the West Country we took a discarded envelope and wrote down as many as we could think of, or find when visually perusing the maps of the 1920 Times Survey Atlas of the World.

There was no gazetteer, and had there been we probably would have considered that cheating. We also decided amongst the three of us that at least one of us would have had to heard of the place, and that rivers and bodies of water did not count. (Sorry Aral Sea and Sea of Azov! No admittance!) Countries, however, do count.

Excitement grew as we neared 100 places, and I was very proud to have topped off the century with Tuam in the motherland, but further examination reveals our calculations had been faulty and we came up with 110 places. (Drink had been taken, the reader will not be surprised to learn.)

Anyhow, here is the list we came up with, in the order in which the names were summoned by collective thought. (more…)

What Huxley’s Got on Orwell

Comparing dystopic visions of the English twentieth century

by ALEXANDER FRANCIS SHAW

Aldous Huxley wasn’t as good a writer as George Orwell but in several ways his Brave New World exceeds the prescience of 1984.

Huxley understood how society would respond if the laws of human ecology were to change. In a mechanised age, useless activity would become a necessity, while medical revolution and sexual deregulation in turn become the germ of totalitarianism. Orwell and just about everyone else since have had the opposite idea – that the libertines would be the liberators – and the fever-pitch of this very delusion forms the central tenet of Huxley’s dystopia.

Both visionaries describe state censorship, but in Huxley’s Brave New World one recognises eery pre-echoes of ‘Woke culture’ in an opiate-addled society which has to conceal its operational ethos from its own general consciousness in order to keep itself functioning smoothly.

With Orwell – the human struggle is represented as Man versus The State. Huxley recognised, as we are now encouraged not to, that society is the product of biology and, provided that people’s biology can be conditioned correctly, the state can foster grass-roots totalitarianism without the use violent coercion.

Neither dystopia has been fully realised – but in Orwell’s case this has been because progress has provided its own remedies (nobody could have imagined in the 1940s that telescreens would also be a conduit of private interaction for dissenters’ online discourse). One gets an unsettling feeling that Huxley’s medical dystopia is still developing in 2021 with no solutions in sight.

Rather than solve the riddle of human happiness, the citizens of Brave New World condemn those who fail to gloss over their displeasure with life through the mollifying comforts of sex and tranquillisers. Science becomes a branch of pragmatism, wielded by social engineers who can no more observe their own fields than look at their own eyeballs.

We are left with the question of how an outsider, possessed of higher directives than his own hedonism, might react to such a society?

Huxley answers this by introducing a Linda and her son, John, who live in a ‘savage reservation’ where medical advances have not been imposed. Traditional sexual morality is thus observed by the occupants along with – shudder! – family life and religious practices and other pursuits which lend meaning to their backward lives.

Linda arrived in the reservation by accident, having been born and acculturated in the ‘civilised world.’ She teaches her son how to read, but brings them both into disgrace with her promiscuity, so that John retreats into the comforts of a book which happens to be ‘The Complete Works of William Shakespeare.’ In Shakespeare, John finds the words that enable him to assert himself both on the reservation and – to the curiosity of his minders – when he finally returns to civilisation.

I sense that Orwell would have furnished John with a lowlier reference-point to human nobility and driven the same points home more poignantly with a dog-eared copy of Paris Match. But, as I said, Huxley was a better visionary than he was a wordsmith.

Once in the ‘civilised world’ John falls in love and faces a problem which, less than a century after Huxley’s work was published, defines what is perceived as a ‘crisis of masculinity’: how to court a woman who gives herself out to dozens of men regardless of merit. Unable to disabuse himself of his chivalric values – and unwilling to accept her worthless sexuality when she freely offers herself to him – John becomes what we would now call a proto-“incel” and dies, as the carnal realists of the toxic chatrooms might anticipate, on the end of a rope.

Smokescreens of happiness and delusion are maintained with a tranquilliser called Soma. Much as anti-depressants are a major feature of modernity – their use strongly suggesting that they are employed where artificial economies and casual sex are normalised – one senses that we have not yet perfected the Brave New World’s capacity for total bafflement. Nor has any welfare state or medical advancement completely collectivised the process of raising children.

This tranquillised social order is upheld by World Controller Mustapha Mond, Huxley’s benign analogue to Orwell’s Big Brother and on that account one of the few people in this dystopia who has achieved any kind of true satisfaction himself. Mond’s discourses bring Huxley to the place of scientific observation in the stable technological order:

‘once you start admitting explanations in terms of purpose – well, you don’t know what the result might be…’

In other words: Heaven forbid anyone should question the dogmas of settled science.

In terms of who may be allowed to see through the delusion, Mond likens the social hierarchy to an iceberg – with 10 per cent above the surface and 90 per cent below. Maverick, enquiring minds must either be sent to isolated communities or – like himself – shoulder the burden of everyone else’s delusion.

Despite Orwell’s predictions of people cowering under state tyranny and violence, Huxley’s work remains the creepier for its ability to get under the skin of the liberal society that we find familiar.

How much worse is it to read of a dystopia in which, by our own liberated will, we are complicit?

How to deal with ‘Direct Action’

A lesson from the experienced generation of not so long ago

BRITONS have a habit of being slow to move initially but they do get their act in order sooner or later — and usually in time to prevent disaster. Many in the metrop. have been damned irritated that the police seemed impotent when the fascist death cult “Extinction Rebellion” first reared its ugly head.

“XR” prevented working-class Londoners from getting to work on the Underground and seized bridges to publicise their claim that — despite global agricultural yields being higher than ever before in human history — we are somehow all going to be starving in a few years’ time due to “climate catastrophe”.

Nonetheless, having returned from Guernsey this morning, I find the streets of London pleasantly filled with the flying squads of the Metropolitan Police. The boys in blue are moving about in rapid response units, ready to deploy immediately whenever and wherever the Extincto-Nazis rear their ugly heads, thus keeping the streets open to all comers (bar those with nefarious designs of un-civic disorder).

“XR” are not the first to threaten (nor to deliver) “direct action”, but I was heartened when a friend shared this splendid example of how to deal with irate students allegedly delivered by the Warden and Fellows of Wadham College, Oxford, in 1968:

Dear Gentlemen,

We note your threat to take what you call ‘direct action’ unless your demands are immediately met.

We feel it is only sporting to remind you that our governing body includes three experts in chemical warfare, two ex-commandos skilled with dynamite and torturing prisoners, four qualified marksmen in both small arms and rifles, two ex-artillerymen, one holder of the Victoria Cross, four karate experts and a chaplain.

The governing body has authorized me to tell you that we look forward with confidence to what you call a ‘confrontation,’ and I may say, with anticipation.

This was less than a quarter-century after the victory of the Second World War, so Wadham could call upon an experienced gang to fill the ranks of its fellowship in those days.

I suppose Maurice Bowra was Warden of Wadham at this time. While a renowned buggerer, he did manage to die with a knighthood, a CH, and the Pour le Mérite (civil class) — which is not a bad innings all things considered.

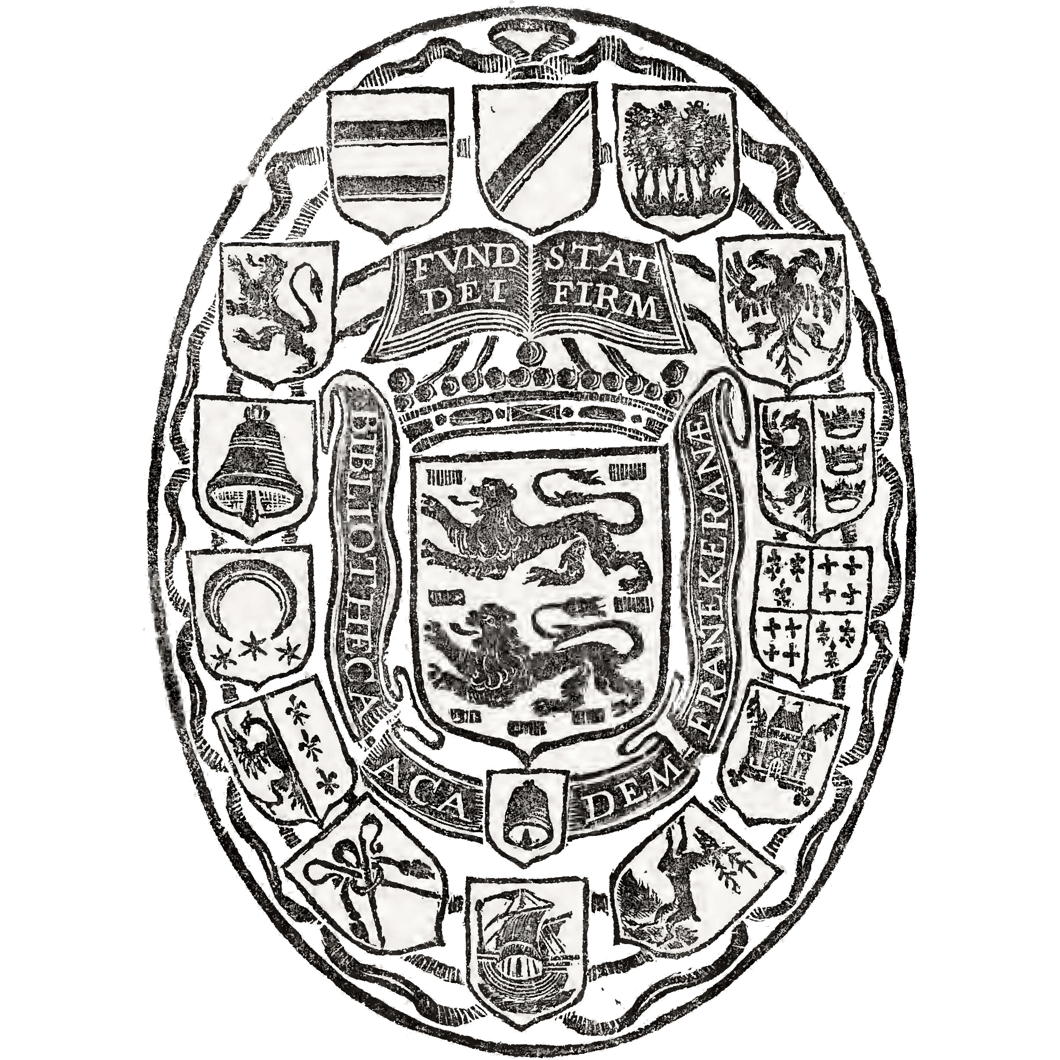

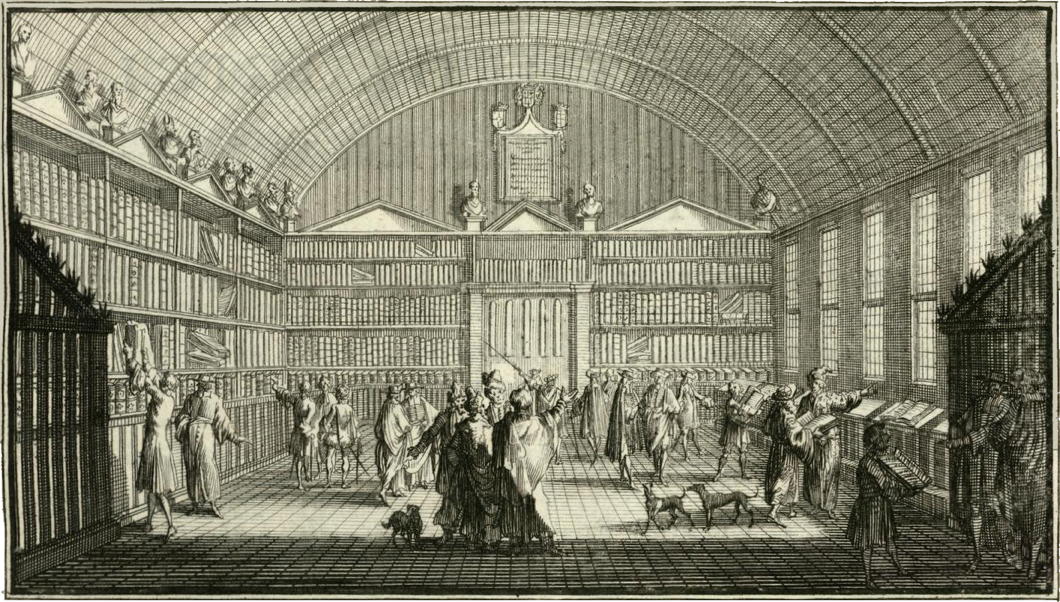

The University of the Frisians

AMONG THE CURIOUS customs of the Netherlandish universities is a unique privilege whereby Frieslanders who are postgraduate students at the Rijksuniversiteit Groningen may defend their thesis in the Church of St Martin in Franeker. This privilege is also extended to those whose dissertations are on Frisian subjects or themes. The reason for this is that Franeker — one of the historic eleven cities of Friesland and today a town of 12,000 souls — formerly had a university of its own.

The University of Franeker (or Academy of Friesland) was established in 1585 by Willem Lodewijk of Nassau-Dillenburg, stadthouder of Friesland, as a Protestant foundation in the former cloister of the Canons Regular of the Order of the Holy Cross (sometimes called the Crosiers) whose confiscated property helped fund the new university.

As the only institution of higher learning in the northern part of the United Provinces, the University of Franeker met with some success in its early decades and its Protestant theological faculty earned particular reknown.

Its most famous student — so far as I am concerned — was a young Petrus Stuyvesant who studied philosophy and languages at Franeker in the 1610s before being sent to be governor of New Amsterdam. Unfortunately the revelation of an amorous relationship with his landlord’s daughter prevented young Stuyvesant from completing his studies.

From 1614 onwards, however, Franeker found a strong competitor when a university was founded in Groningen that was more successful at drawing in students from Germanic East Frisia. By the 1790s it had only eight students.

In 1811, when the Netherlands were directly annexed to the French Empire, Napoleon abolished the university entirely, alongside those of Utrecht and Harderwijk.

Its revival under the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815 met with little success as Franeker was denied the ability to grant doctorates and in 1843 even this academy was finally suppressed.

Incidentally, the fourteenth-century Martinikerk where Frisians can defend their theses today is also the only surviving medieval church in Friesland that has an ambulatory — and restoration work in the 1940s revealed twelve pre-Reformation frescoes of saints.

a Northumbrian of Frisian and New Yorkish origin

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories