About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

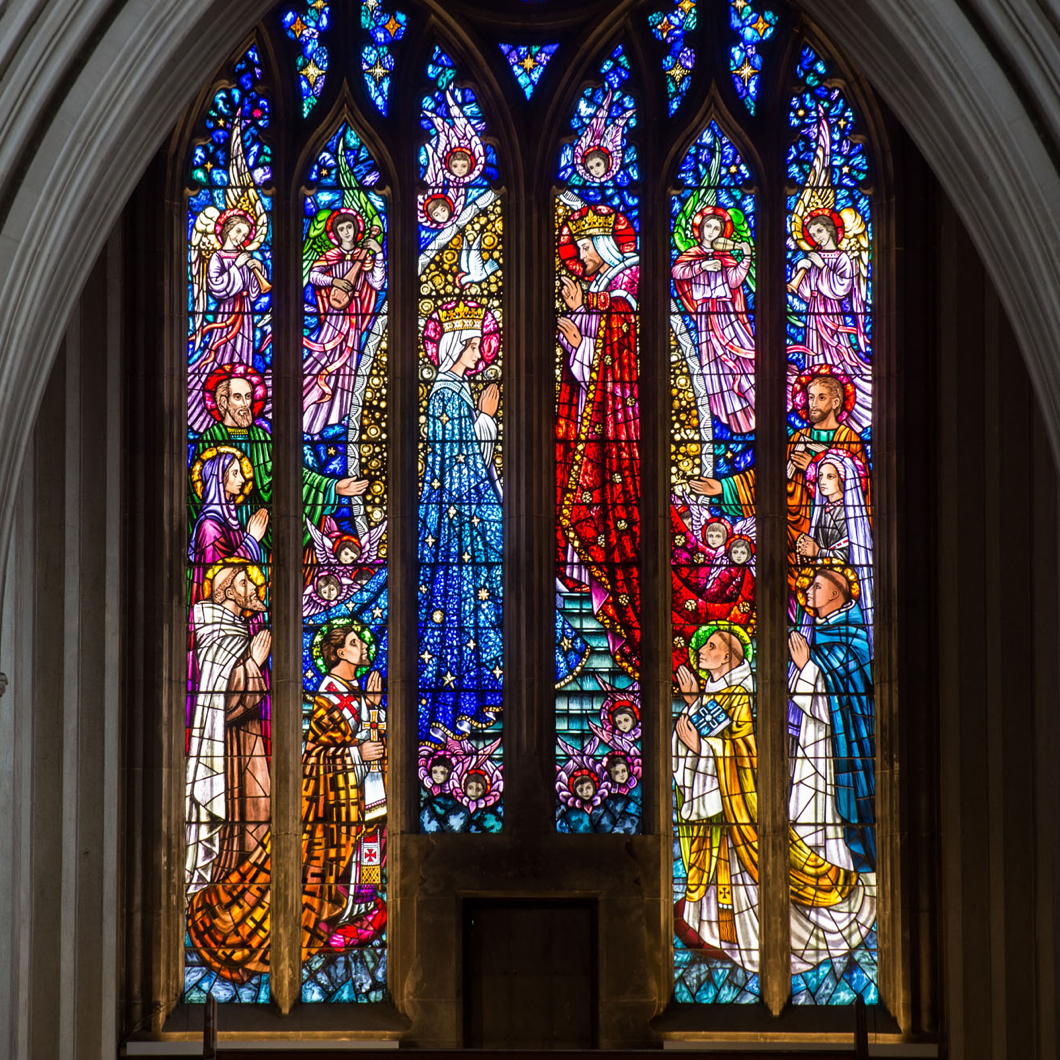

LMS Quarterly Mass at St George’s

the regular quarterly Extraordinary Form Mass organised by the Latin Mass Society of England & Wales

will take place at

The Lady Chapel is to the right at the end of the north aisle of the Cathedral (on your right as you enter).

Earlier in the morning, as every Saturday at St George’s Cathedral, there will be Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament from 10:00 to 11:00 am, during which time Confessions will be heard.

The Installation of the Grand Prior of England

All photos © Grand Priory of England

Msgr John Armitage gave this sermon on the occasion.

“Brethren, we know that in everything God works for good with those who love him, who are called according to his purpose.”

In a world that seeks fulfilment by seeking what I want, the Church is the witness, that the good we encounter in our world, is the result of the God who works for this good through those who love him, for the whole of creation is called according to his purpose. Only love can give our lives meaning and purpose, and our true fulfilment is a consequence of not doing what I want, but seeking, sharing, and doing what we need, building the common good of all humanity. The Church has its fair share of those of us who do what we want, but our Order has been greatly blessed by those whose lives had been dedicated to building up the body of Christ, living witnesses of what we need, these people we call saints.

Our founder Blessed Gerard, was known by his contemporaries as “the humblest man in the East, a servant of the poor, devoted to pilgrims, of simple appearance, but shining forth with his noble heart.” In the darkness of 1941 Pope Pius XII in an address to the Order, explained the true meaning of nobility:

“In these poor, these orphans these wounded these lepers, lie you own title deeds of nobility, received at Bethlehem from the King of Kings who being rich became poor, that by his poverty you might be rich.”

In every moment in time there is a grace to be found, and the history of the Church shows us that it is in the darkest moments that God’s grace is most profound. “For where sin increased, grace increased all the more.” (Romans 5:20)

When Pope Gregory the Great sent St Augustine to evangelise the pagan English, Rome was a dark and dangerous place, the Roman Empire was collapsing, the barbarians were at the gates, plague was rife, yet the successor of Peter sent a frightened monk to the edge of a crumbling empire. Pope Gregory understood the wisdom of the modern saying “Better to light one candle than to curse the darkness.”

Augustine built a monastery, it was the spiritual foundation, lighting the flame of faith for his companions to spread the Good News in a dark and dangerous land. All works of the Gospel must be based on firm spiritual foundations which from time to time must be renewed. (more…)

Elizabeth II

ELIZABETH II

the United Kingdom

of Great Britain & Northern Ireland

Canada

Australia

New Zealand

Jamaica

the Bahamas

Grenada

Papua New Guinea

the Solomon Islands

Tuvalu

Saint Lucia

Saint Vincent & the Grenadines

Antigua & Barbuda

Belize

and Saint Kitts & Nevis

quondam Queen of South Africa, Pakistan, Ceylon, Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Tanganyika, Trinidad & Tobago, Uganda, Kenya, Malawi, Malta, the Gambia, Guyana, Barbados, Mauritius, and Fiji

Head of the Commonwealth

Defender of the Faith

Duke of Normandy

Duke of Lancaster

Lord of Mann

Head of the House of Windsor

L’Élysée à la plage

The Fort de Brégançon: Riviera Retreat of France’s Presidents

When France’s head of state needs to let his hair down every summer, the Republic has a convenient presidential residence just for him to do so: the Fort de Brégançon on the Côte d’Azur.

There has been a fortress here since at least mediæval times, and Gen. Buonaparte (later emperor) ordered its ramparts renewed after the retaking of Toulon in 1793. It continued to serve military purposes until 1919, but in 1924 it was leased out to a local mercantile family, the Tagnards.

They passed their lease on to the former government minister Robert Bellanger, who improved the island greatly, connecting it to the water and electricity supply, building the causeway linking it to the mainland, and laying out the Mediterranean garden. Bellanger’s leased expired in 1963 and Brégançon returned to the property of the state.

President de Gaulle stayed a night on the island in 1964 but found the bed too small and the mosquitos too bothersome. Nonetheless, his wartime comrade René-Georges Laurin (mayor of Saint-Raphaël up the coast) convinced him it would make a suitable summer residence that befitted the dignity of France’s head of state.

The architect Pierre-Jean Guth was seconded over from the Navy to adapt and update the fort to this end. The rooms are a little small, but their cozy intimacy adds to the fort’s informality. The presidential bedroom features a Provençal bed facing the sea with a view towards the nearby island of Porquerolles.

Pompidou and Giscard enjoyed the island but Mitterand mostly neglected the island except when welcoming Chancellor Kohl and Taoiseach Garrett Fitzgerald. Chirac and his wife took up Brégançon and were often seen by the locals on their way to Mass.

Sarkozy liked to be photographed on his jogs from the island but after he abandoned his wife and took up with his mistress he preferred holidaying at Carla Bruni’s far grander and more comfortable summer residence.

Hollande opened the fort up to public visitors, hoping to recoup some of the costs of maintaining the property. Macron has taken to the island frequently for his summers, for meetings with foreign leaders, and for working weekends with his ministers.

With summer fires raging, a minority in parliament, and myriad other problems brewing, no doubt Macron has much on his agenda.

All the same, for France’s sake, we can’t help but hope Monsieur le Président has a happy holiday. (more…)

The Accident of Birth

A king is a king, not because he is rich and powerful, not because he is a successful politician, not because he belongs to a particular creed or to a national group. He is king because he is born.

And in choosing to leave the selection of their head of state to this most common denominator in the world — the accident of birth — Canadians implicitly proclaim their faith in human equality, their hope for the triumph of nature over political manoeuvre, over social and financial interest; for the victory of the human person.

— Fr Jacques Monet SJ FRSC

A Few Quick Questions

Here are my answers from today, republished with the kind permission of the editor.

Always begin with Mass – I dislike leaving it to the evening. Usually at the Brompton Oratory, or at St George’s Cathedral right across the street from me in Southwark.

Following the news or taking it easy this August?

Picked up Le canard enchainé this week, which I do from time to time. Good to add words to my lexicon (flache-baque) and try and keep up with things the other side of la Manche.

Other than that, avoiding the news like the plague.

Breakfast plans?

Cappuccino and pain au chocolat. Boring but reliable.

What’s on the soundtrack lately?

‘Albi Ya Albi’ by Nancy Ajram and some beautiful Stradella arias.

And the bookshelf?

Just finished another Maigret, some Robertson Davies, and Seb Faulkes’ Bond novel. Now on Tom Gallagher’s bio of Salazar, Jan Morris’s Venice, and one of the Zen detective novels.

Been reading a lot of Leonardo Sciascia lately – his name is such a pleasure to pronounce – and I’ve got some John B. Keane and Anthony Levi’s biography of Richelieu on the way. Jaan Kross is sitting on the pile. And Juan Gabriel Vasquez, who I’ve enjoyed greatly.

A glass of something?

A good cold glass of white Burgundy outdoors, although in this heat a gin-and-tonic is always a welcome relief.

Lemon or lime?

Lemon, always – unless it’s Archangel, a delicious gin a mate of mine makes in Norfolk. Always a slice of orange with Archangel.

Sunday evening routine?

I usually try to have a night in on Sunday, but yesterday ended up in Hampstead meeting Isaac and Joe for a pint before Tijmen got us round for a Scotch (or “uno Scotch-ito” as he confusingly calls it) on the terrace as the sun went down.

The NW3 crew usually refuse to ever leave their postcode, but I drop in often and I can see why.

What’s on the menu lately?

A friend came round Saturday night for a quick dinner pre-pub session. I made some pappardelle, chopped up the leftover sausage I’d had at lunch and threw it in a pot with some sun-dried tomatoes, rosemary, thyme, lots of butter, pinch of dried Italian peppers, red pesto, mixed it all up and served with some ripped leaves of basil. Went down pretty well.

What’s the week ahead hold?

Two dinner parties – one Hungarian-Jewish/French in Putney, the other Welsh/German/French in Soho – and hoping to make it to ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ at the Prince Charles Cinema this Wednesday.

Other than that, a fair bit of work and writing and I hope a lot of reading in the garden.

Enjoy!

Thank you!

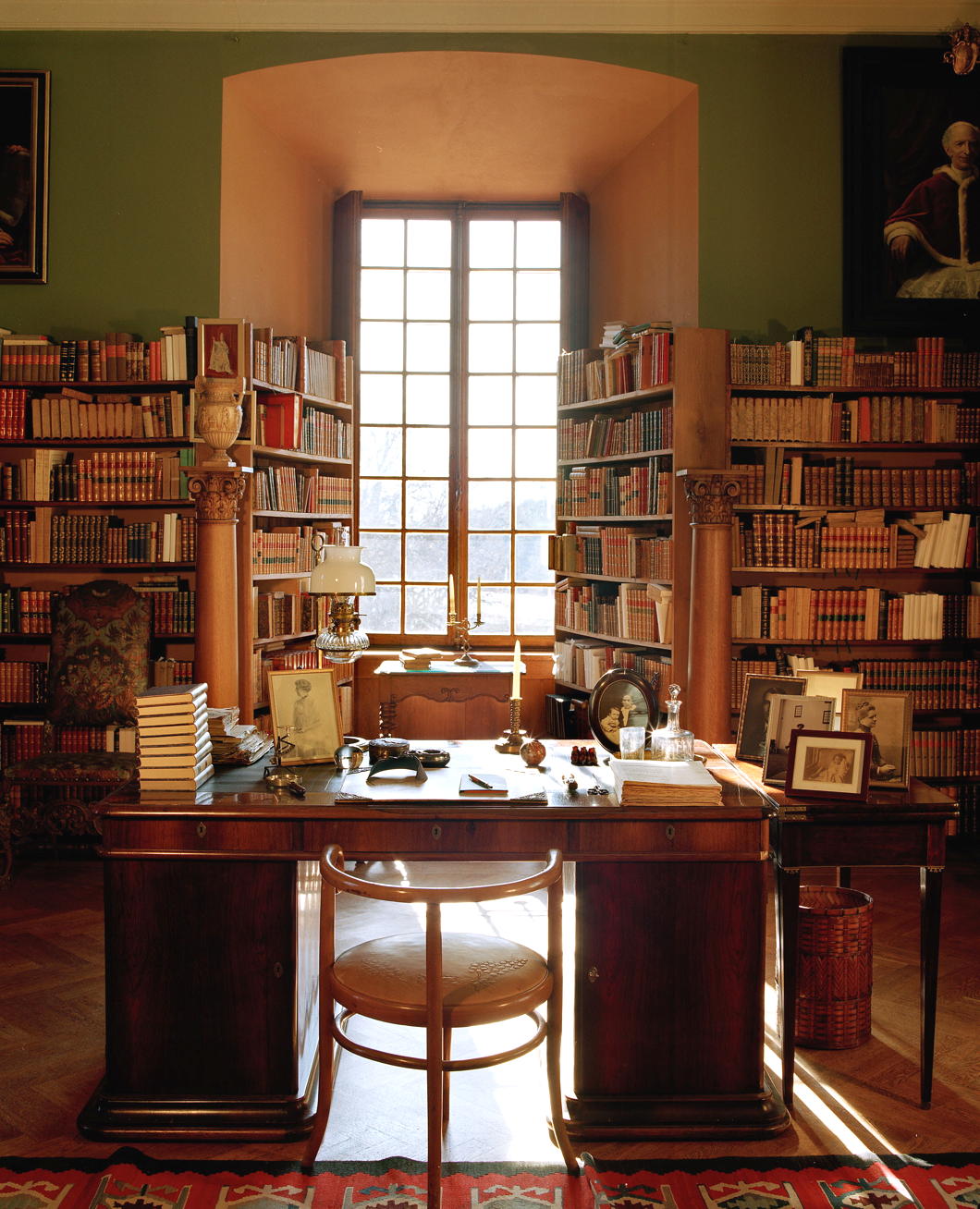

A Desk in Sweden

(In honour of his descendant coming to London for a coffee last month.)

Alys Beach

My list of favourite things starts with sunshine, good architecture, and the beach — Florida’s Alys Beach has all three. This is the third of the communities on the Gulf Coast designed by Duany Plater-Zyberk.

Their first, Seaside — well known as where ‘The Truman Show’ was filmed — is iconic but now feels a little sterile and over-planned. It has earned its place in the history books of urbanism and architecture regardless.

Rosemary Beach, their second development, was a vast improvement and based its architecture on the actual Spanish colonial styles used when the Cross of Burgundy flew over Florida rather than the more Mediterranean-influenced Spanish Colonial Revival of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Alys Beach is a splendid melange — a touch of the Cape Dutch, Bermuda here, the Maghreb there, and every now and then a hint of the French Caribbean. And it works: this is one of the most successful attempts at a beautiful and pleasing urban arrangement in twenty-first century America.

If any criticism can be issued it’s that Alys Beach is a holiday destination that will never be a “real” community where most people dwell all year round.

But if I was sitting en famille round a rooftop firepit watching the sun go down, I don’t think I’d complain.

St George’s Basilica, Prague Castle

Monolingual Limitations

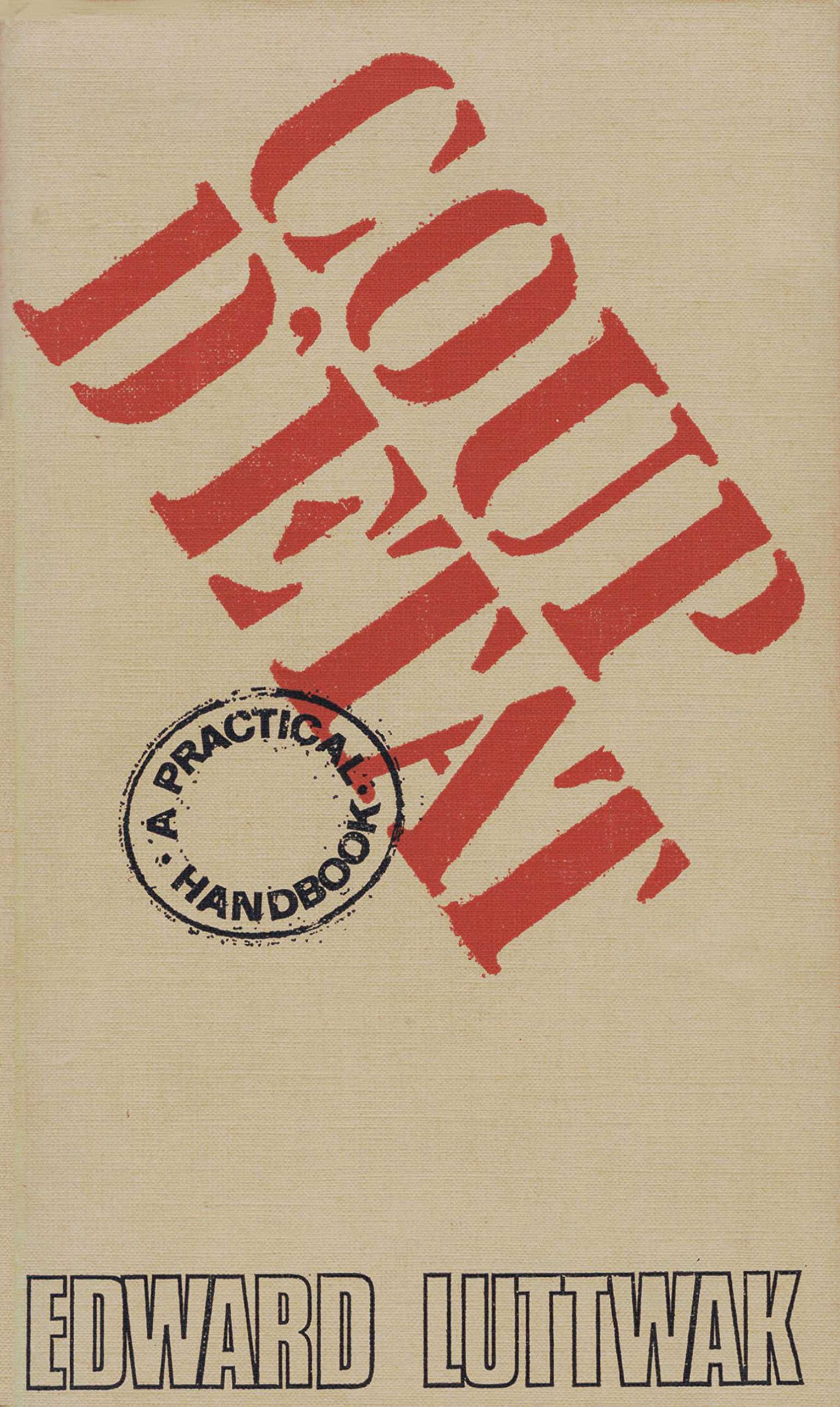

I’m  sure I wasn’t the only twelve-year-old whose favourite book was Edward Luttwak’s delicious Coup d’État: A Practical Handbook — an excellent gift from my father. The work gave me a lifelong fascination with the golpe de Estado, a phenomenon of government all too increasingly a rare species in our post-Cold War era.

sure I wasn’t the only twelve-year-old whose favourite book was Edward Luttwak’s delicious Coup d’État: A Practical Handbook — an excellent gift from my father. The work gave me a lifelong fascination with the golpe de Estado, a phenomenon of government all too increasingly a rare species in our post-Cold War era.

Just about everything written or said by Luttwak — lately a cattle farmer in Paraguay — is worth reading or listening to. For a start you could read his contributions to the LRB or to the excellent American Jewish Tablet magazine.

I have been waiting for someone to offer a refutation of his provocative Prospect essay on how the Middle East is less relevant than ever, and it would be better for everyone if the rest of the world learned to ignore it.

David Samuels chat with Luttwak this month on the subject of the Three Blind Kings — Putin, Biden, and Xi — offers some superb insights as well as amusements.

Among the lessons that Luttwak is keen to drive home — and he says so over and over and over again on Twitter — is that American intelligence-gathering (and government in general) is too reliant on technology with too few officials, analysts, and operatives actually learning the language of those they are attempting to surveil.

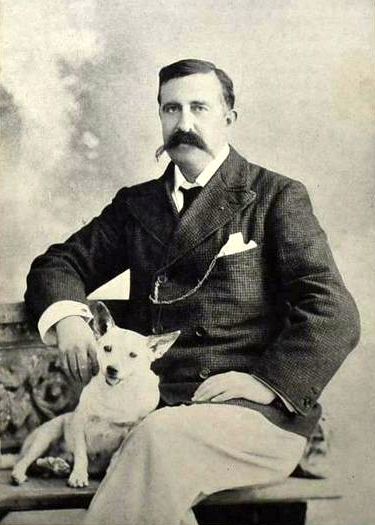

That this state of monolingual limitation was not always the case was driven home in an excellent piece by Jonathan Gaisman in the February 2022 New Criterion concerning Sir Ronald Storrs (left, 1881–1955) — “the most brilliant Englishman in the Near East” as Lawrence of Arabia called him.

That this state of monolingual limitation was not always the case was driven home in an excellent piece by Jonathan Gaisman in the February 2022 New Criterion concerning Sir Ronald Storrs (left, 1881–1955) — “the most brilliant Englishman in the Near East” as Lawrence of Arabia called him.

An accomplished Arabist, Storrs served as Oriental Secretary for the British administration in Egypt before going on to become Military Governor of Jerusalem, Governor of Cyprus, and Governor of Northern Rhodesia, from which role he retired on health grounds, returned to the metropole, and served a few years on London County Council.

Gaisman relays this delicious anecdote from the British official’s 1937 autobiography Orientations:

Sometime in 1906 I was walking in the heat of the day through the Bazaars. As I passed an Arab café an idle wit, in no hostility to my straw hat but desiring to shine before his friends, called out in Arabic, “God curse your father, O Englishman.”

I was young then and quicker-tempered, and foolishly could not refrain from answering in his own language that I would also curse his father if he were in a position to inform me which of his mother’s two and ninety admirers his father had been.

I heard footsteps behind me and slightly picked up the pace, angry with myself for committing the sin [of] a row with Egyptians. In a few seconds I felt a hand on each arm. “My brother,” said the original humorist, “return, I pray you, and drink with us coffee and smoke. I did not think that Your Worship knew Arabic, still less the correct Arabic abuse, and we would fain benefit further by your important thoughts.”

Gaisman further spoils us with another excellent story — this time about Storrs’ predecessor as Oriental Secretary in Cairo, Mr Harry Boyle:

[Boyle] was taking his tea one day on the terrace of Shepheard’s Hotel when he heard himself accosted by a total stranger: “Sir, are you the Hotel pimp?”

“I am, Sir,” Boyle replied without hesitation or emotion, “but the management, as you may observe, are good enough to allow me the hour of five to six as a tea interval. If, however, you are pressed perhaps you will address yourself to that gentleman,” and he indicated [the self-made tea magnate] Sir Thomas Lipton, “who is taking my duty; you will find him most willing to accommodate you in any little commissions of a confidential character which you may see fit to entrust to him.”

Boyle then paid his bill, and stepped into a cab unobtrusively, but not too quickly to hear the sound of a fracas, the impact of a fist and the thud of a ponderous body on the marble floor.

Boyle’s 1937 obituary in the Palestine Post noted he was “a gifted linguist, speaking no fewer than twelve languages”. When Lord Cromer was Britain’s proconsul in Egypt, he and Boyle were such frequent perambulators along the Nile that Boyle earned the nickname Enoch, for he “walked daily with the Lord”.

Boyle’s 1937 obituary in the Palestine Post noted he was “a gifted linguist, speaking no fewer than twelve languages”. When Lord Cromer was Britain’s proconsul in Egypt, he and Boyle were such frequent perambulators along the Nile that Boyle earned the nickname Enoch, for he “walked daily with the Lord”.

During these walks, Cromer was keen to mix with Egyptians of the most humble backgrounds and was aided by Boyle’s linguistic skills. Such was his excellence in Arabic that, returning to Egypt many years later, Boyle was recognised by a peasant farmer many miles outside of Cairo and warmly embraced as the man who used to walk the Nile with the British lord.

“In the hot and brooding nights of the Egyptian summer,” the Post appreciation also relates, “when all who were at liberty to do so had fled to cooler climes, Cromer and Harry Boyle might often have been seen seated after dinner on the veranda of the Agency in Cairo reading aloud alternately passages from the Iliad.”

Perhaps all is not lost. While I can’t speak for the state of the gift of tongues at Langley, at least the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom can launch into Homer, in Greek, from memory.

But Luttwak would surely be right to retort that it is among the mid-level officials and analysts that linguistic skills are most missing — nor are we currently threatened by Athens, Sparta, or Corinth.

Mrs Evelyn Pelosi

I’ve only just heard of the death of Mrs Evelyn Pelosi, who departed this life at the end of last month.

Evelyn was piously devoted to the traditional liturgy of the Church and was a stalwart of the SSPX’s Edinburgh congregation — but she never stood in the way of houseguests attending the FSSP (or even the Novus Ordo!).

Her mischievous deadpan sense of humour was deployed to excellent effect in her occasional role as gypsy fortuneteller at festive events organised by the South Edinburgh Conservatives in the 1990s.

Another hat she wore was Convenor of the Monarchist League of Scotland (an entity whose events attracted a curious clientele) and from an early age she had a great devotion to South Africa where she visited me in Stellenbosch and introduced me to friends in the pro-life movement in Cape Town.

In the Seventies and Eighties, whenever she thought journalists in the Caledonian dailies were too forgiving of occasional terrorist outrages by the ANC their editorial offices frequently found themselves in receipt of a letter signed by Mrs E. Pelosi, Friends of Christian South Africa.

Mangosutho Buthelezi was among the many well-wishers whose cards could be found overflowing on the chimneypiece of her home in the Mayfield Road.

I remember watching the premier of the television version of Alexander McCall Smith’s “The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency” at her’s there on Easter Sunday evening in 2008 — an Edinburgh/Southern Africa crossover event if ever there was one.

She was amused but dignified when another woman of her marital surname (but radically different views) ascended the political scene across the Atlantic, but for anyone who knew her Evelyn will always be the only Mrs Pelosi.

May she rest in peace.

Corpus Christi

The Master of James IV of Scotland, Flemish c. 1541; Getty Museum

30 mai 1968

The events of May 1968 have been fetishised by the romantic radical left but ended in the triumph of the popular democratic right. Battered by two world wars, France had enjoyed an unprecedented rise in living standards since 1945 — especially among the poorest and most hard-working — and a new generation untouched by the horrors of war and occupation had risen to adulthood (in age if not in maturity). The ranks of the middle class swelled as more and more people enjoyed the material benefits of an increasingly consumerised society, while those left behind shared the same aspirations of moving on up.

Like any decadent bourgeois cause, the spark of the May events was neither high principle nor addressing deep injustice but rather more base impulses: male university students at Nanterre were upset they were restricted from visiting female dormitories (and that female students were restricted from visiting theirs). The ensuing events involved utopian manifestos, barricades in the streets, workers taking over their factories, a day-long general strike and several longer walkouts across the country.

The French love nothing more than a good scrap, especially when it’s their fellow Frenchmen they’re fighting against. Working-class police beat up middle-class radicals but for much of the month both sides made sure to finish in time for participants on either side to make it home before the Métro shut for the evening. But workers’ strikes meant everyday life was being disrupted, not just the studies of university students. When concessions from Prime Minister Georges Pompidou failed to calm the situation there were fears that the far-left might attempt a violent overthrow of the state.

De Gaulle himself, having left most affairs in Pompidou’s hands, finally came down from his parnassian heights to take charge but then suddenly disappeared: the government was unaware of the head of state’s location for several tense hours.

It turned out the General had flown to the French army in Germany, ostensibly to seek reassurance that it would back the Fifth Republic if called upon to defend the constitution. De Gaulle is said to have greeted General Massu, commander of the French forces in West Germany, “So, Massu — still an asshole?” “Oui, mon général,” Massu replied. “Still an asshole, still a Gaullist.”

The morning of 30 May 1968, the unions led hundreds of thousands of workers through the streets of Paris chanting “Adieu, de Gaulle!” The police kept calm, but the capital was tense and there was a sense that things were getting out of hand. Pompidou convinced de Gaulle the Republic needed to assert itself.

Threatened by a radicalised minority, de Gaulle called upon the confidence of the ordinary people of France. At 4:30 he spoke on the radio briefly, announcing that he was calling for fresh elections to parliament and asserting he was staying put and that “the Republic will not abdicate”.

Before the General even spoke some his supporters (organised by the ever-capable Jacques Foccart) were already on the avenues but the short four-minute broadcast inspired teeming masses onto the streets of central Paris, marching down the Champs-Élysées in support of de Gaulle.

A Home for Bard and Ballet

Sir Basil Spence’s unbuilt Notting Hill theatre

Sir Basil Spence was just about the last (first? only?) British modernist who was any good. His British Embassy in Rome is hated by some but combines a baroque grandeur appropriate to the Eternal City with the crisp brutalism of modernity that makes it true to its time.

In 1963, Spence accepted the commission from the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Ballet Rambert for a London venue to host the performances of both bodies.

The poet, playwright, and theatre manager Ashley Dukes had died in 1959, leaving a site across Ladbroke Road from his tiny Mercury Theatre (in which his wife Marie Rambert’s ballet company performed) for the building of a new hall.

The design moves from the sweeping curve of the street frontage up to a series of angular concoctions and finally the large fly-space above the stage itself.

It made the most of a highly constricted site and would have housed 1,100-1,600 patrons (historical sources vary on this figure). This was a big step up from the old Mercury Theatre which housed 150 at a push.

Ultimately, the plan failed. London County Council was worried there wasn’t enough parking in the area, and the Royal Shakespeare Company was tempted away by the City of London Corporation which was building the Barbican Centre.

Safavid Pottery Tile

A seventeenth-century pottery tile from Safavid Persia — from the collection of the late Pierre Le-Tan.

US Army Chief in London

General James C. McConville, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, dropped into London this week to meet with General Sir Patrick Sanders, who will take over as his British opposite number (Chief of the General Staff) later this year.

Both are the head of their countries’ respective armies and subordinate to overall defence chiefs, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the US and the Chief of the Defence Staff here in the United Kingdom.

General McConville was welcomed to the official Army Headquarters at Horse Guards, Whitehall, by the Major General Commanding the Household Division, Maj. Gen. Chris Ghika.

A contingent from the Coldstream Guards and the Band of the Irish Guards put together a ceremonial display and Gen. McConville took the salute.

Gen. McConville will also deliver the Kermit Roosevelt Lecture at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst this week.

The general’s visit provided a chance to show off the US Army’s new service uniform — modelled on the popular old pinks and greens.

This provides a much welcome alternative to the Dress Blues which, to my mind, make soldiers look like glorified policemen.

As I wrote when discussing similar changes in Peru, it’s not turning the clock back: it’s choosing a better future.

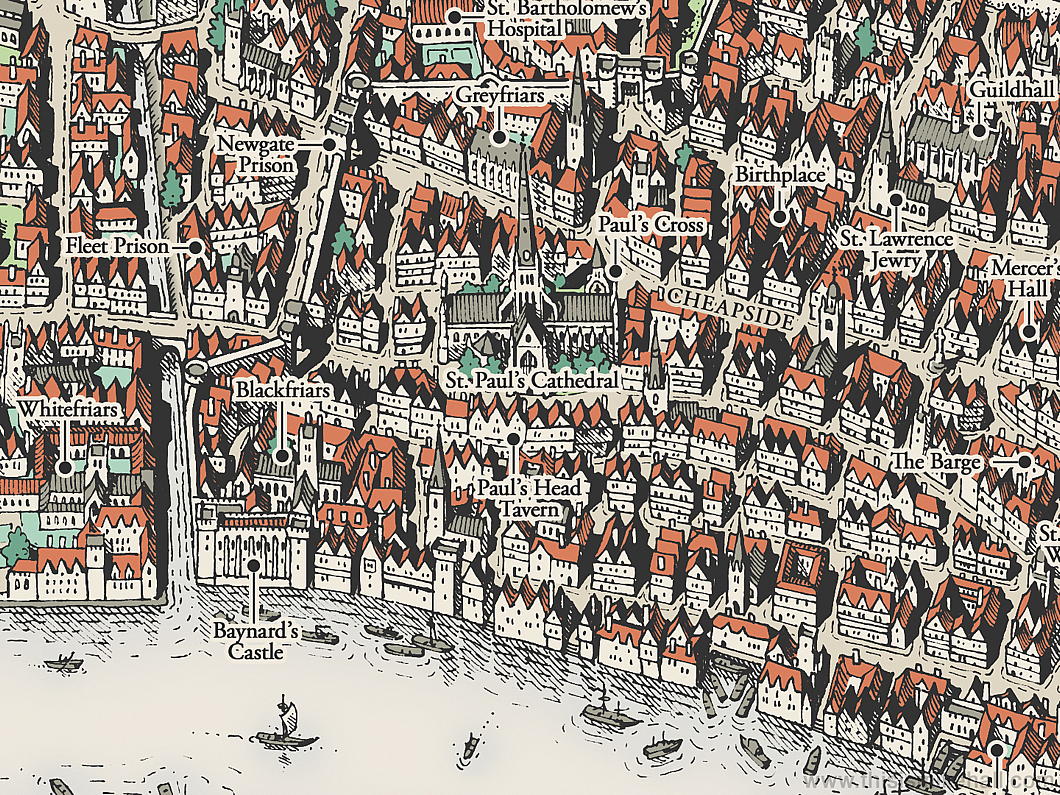

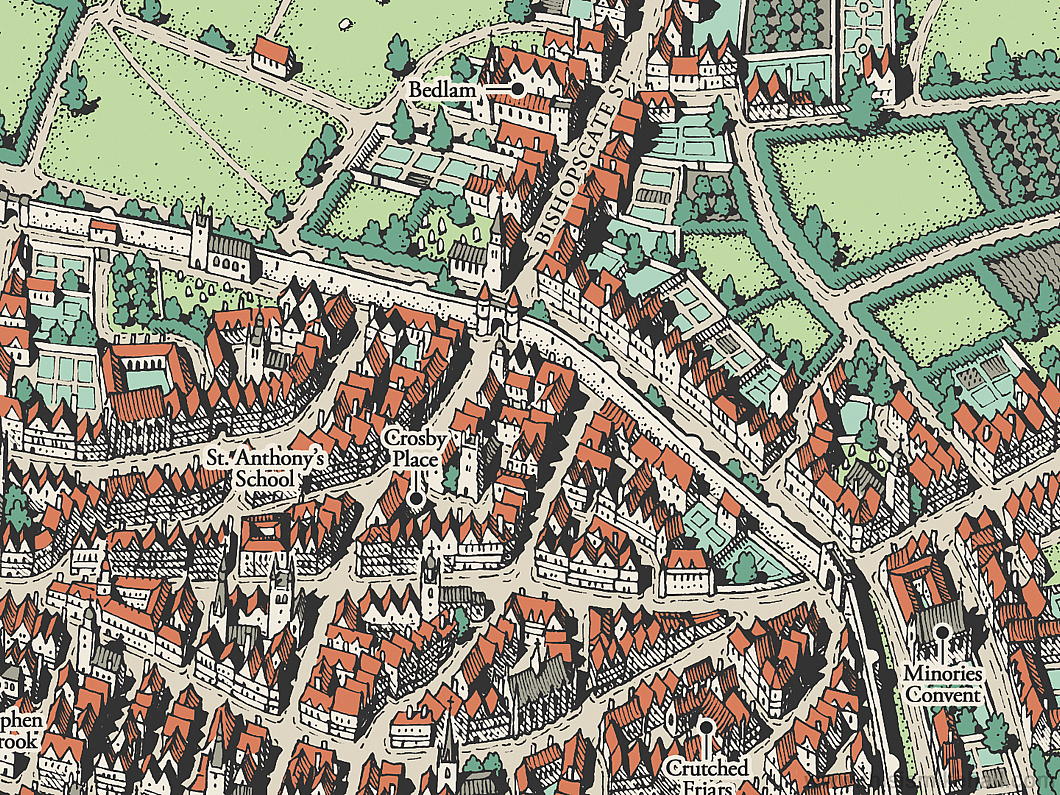

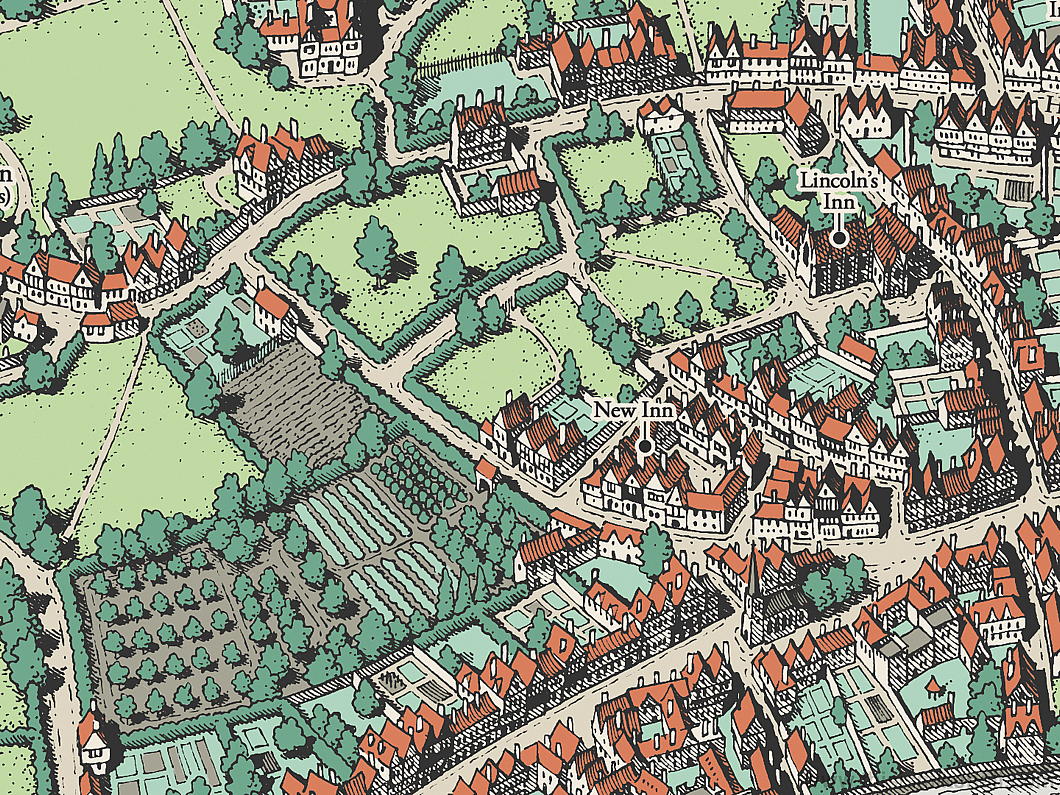

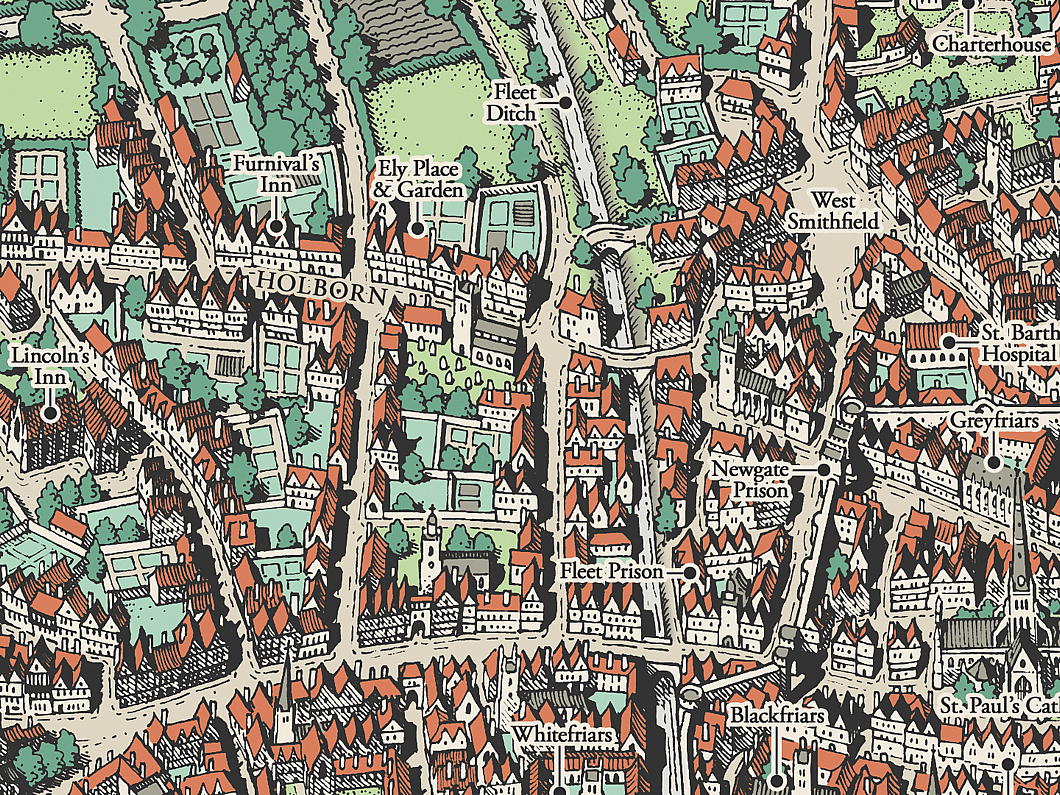

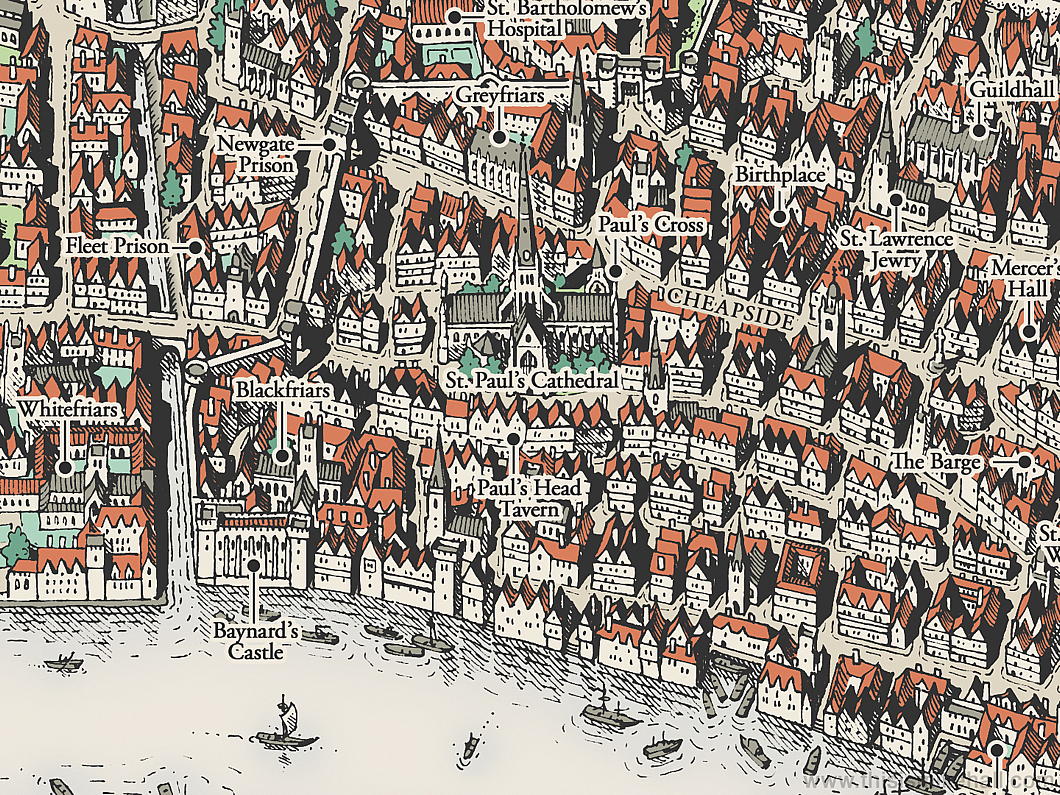

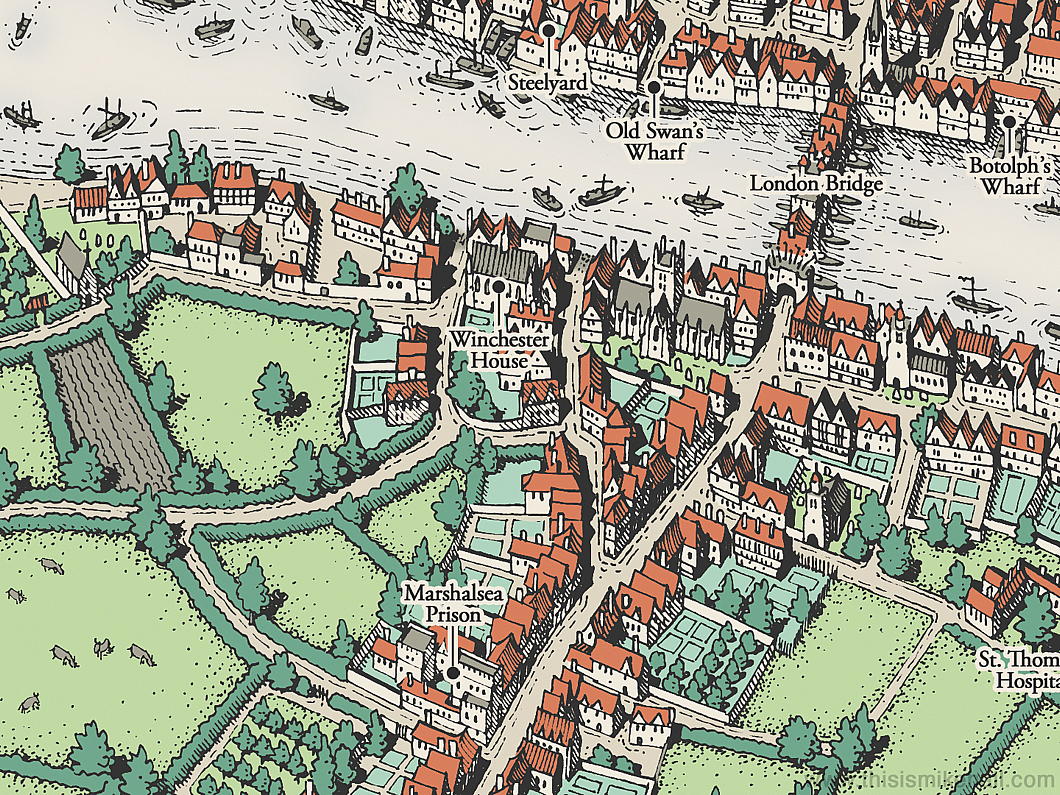

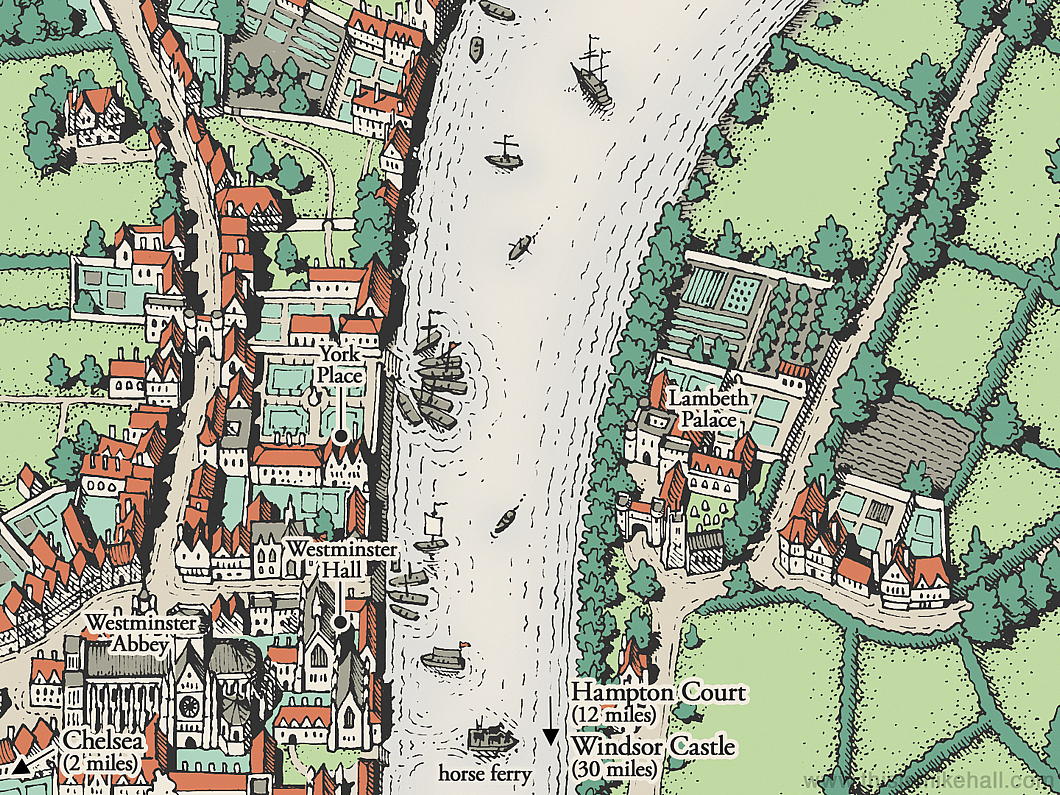

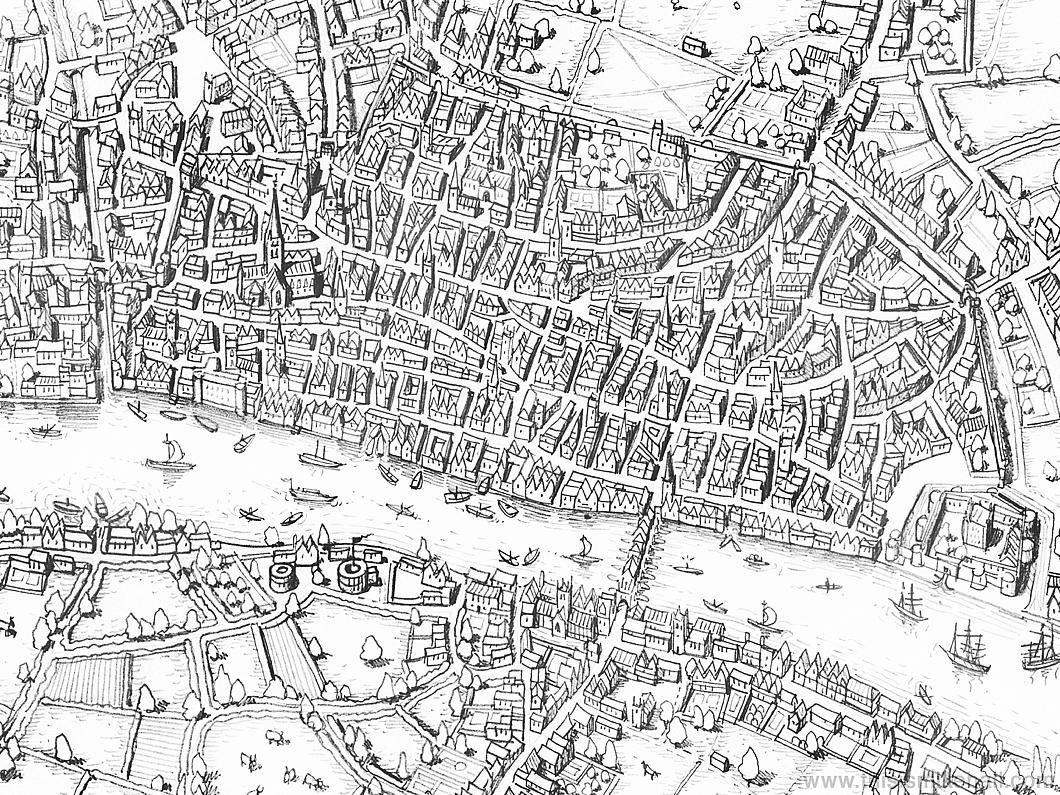

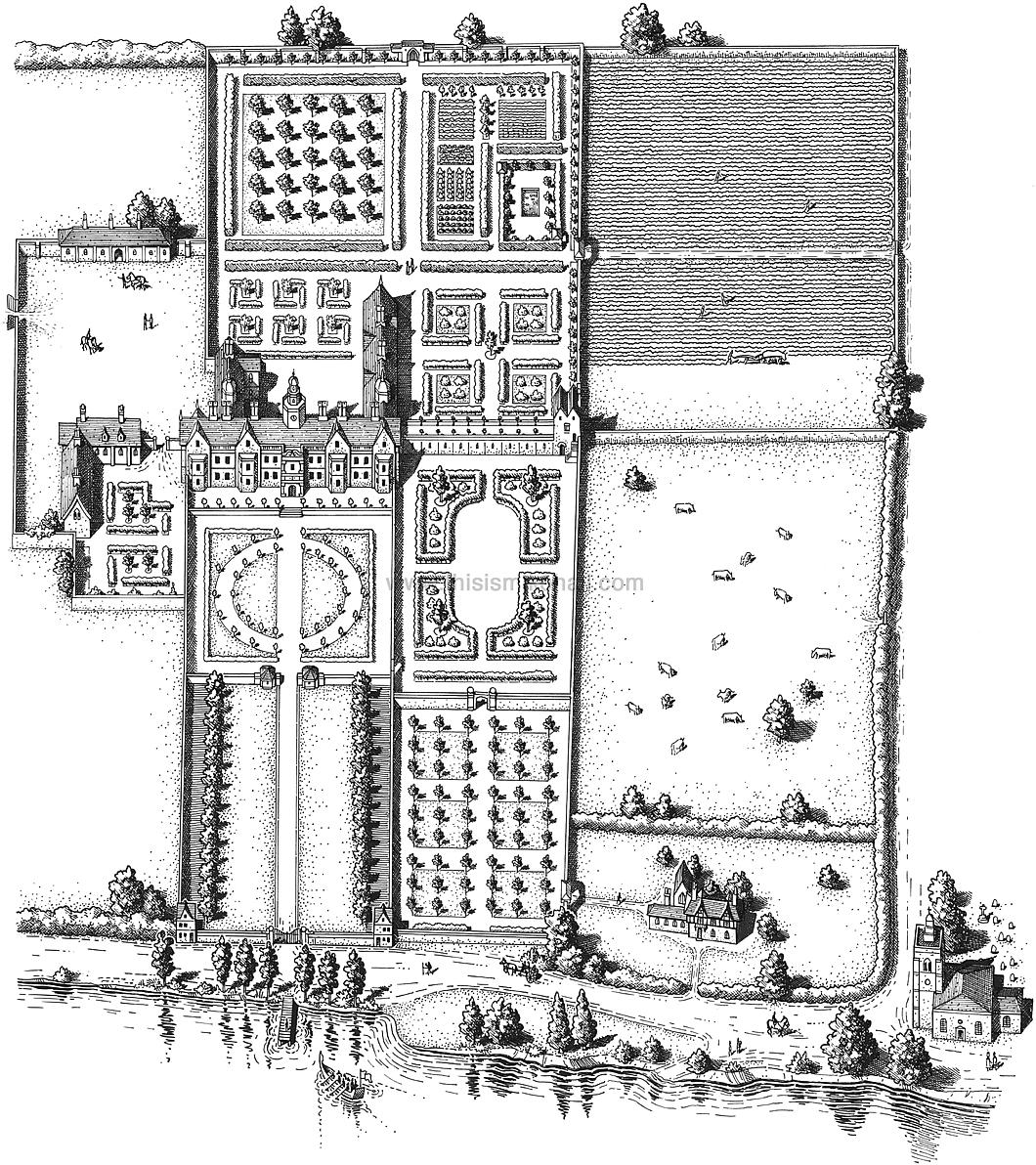

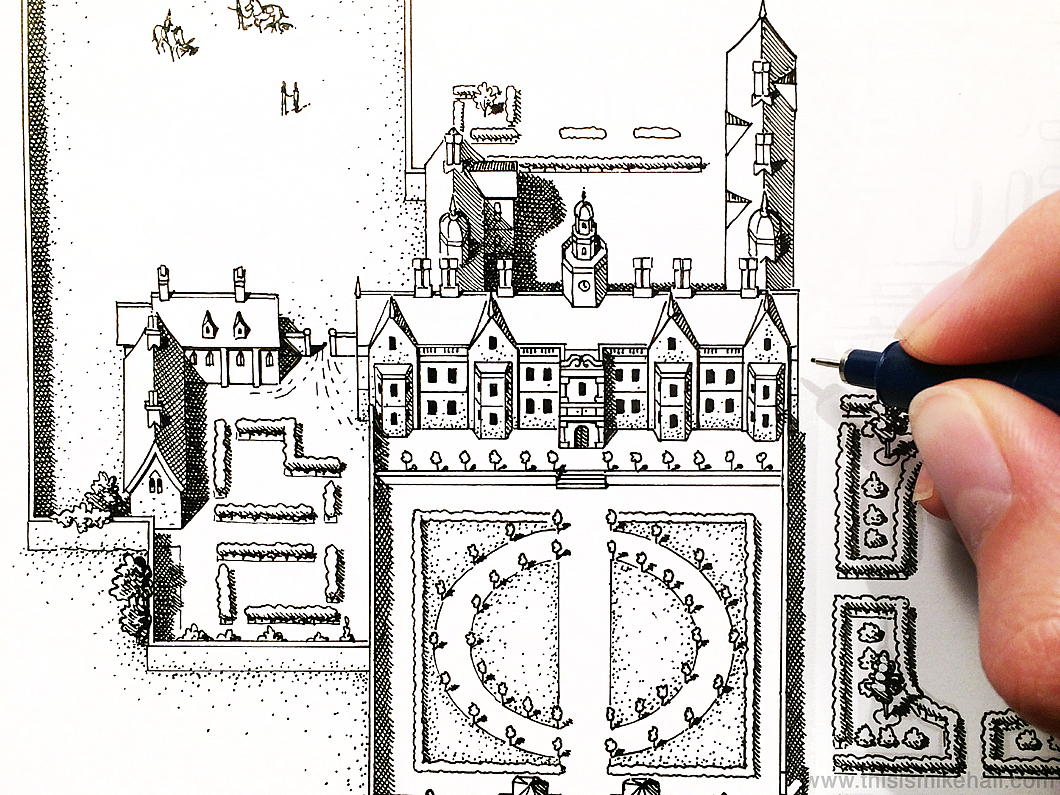

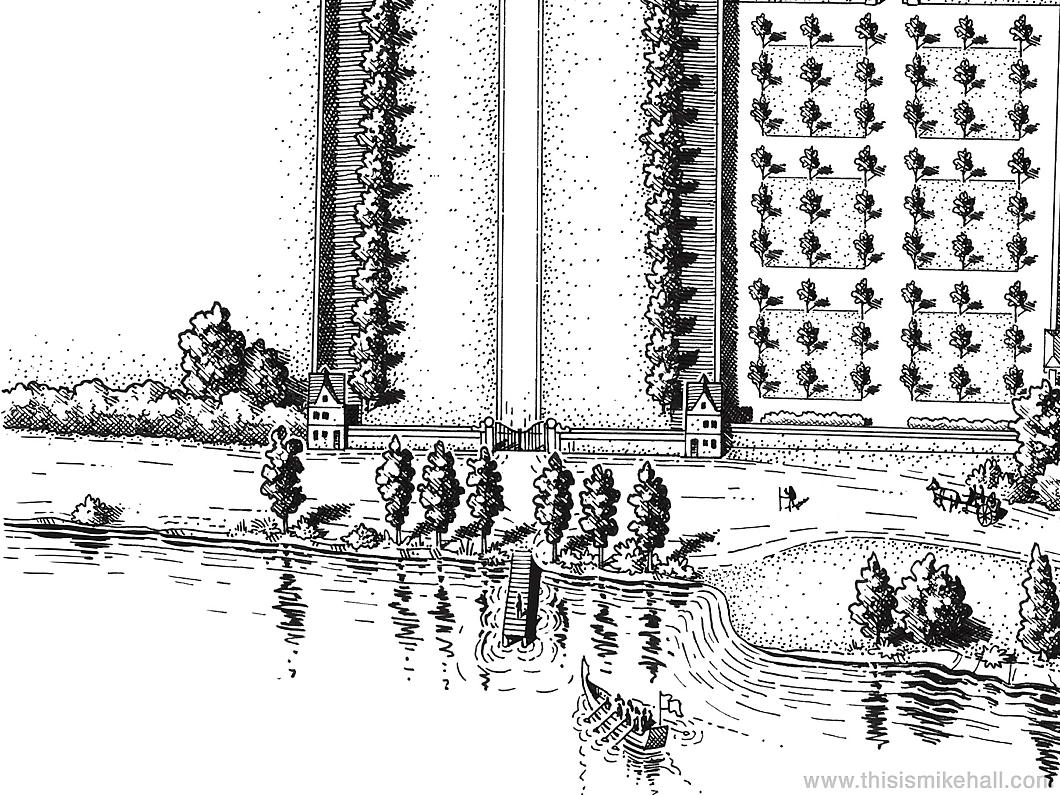

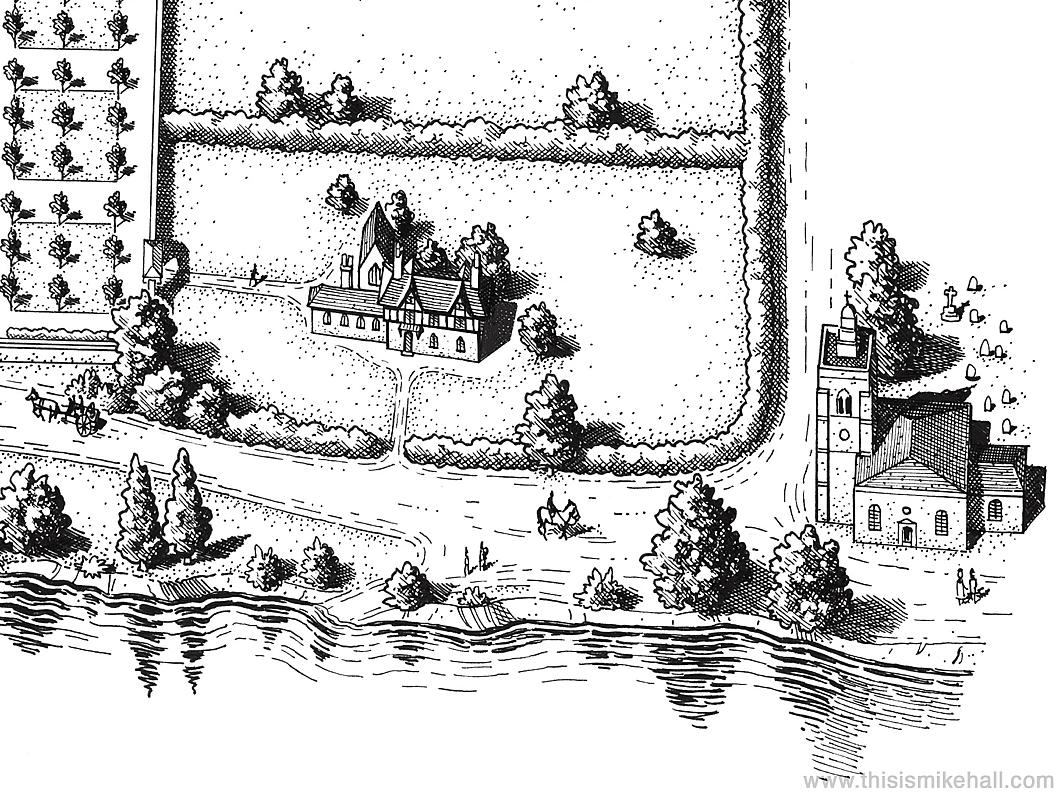

Thomas More’s London

There are almost as many Londons as there are Londoners. There’s Shakespeare’s London, Pepys’s London, Johnson’s London — even fictional characters like Sherlock Holmes have their own London.

The city of Saint Thomas More takes form in a representation made by the excellent map designer Mike Hall, Harlow-born but now based in Valencia.

This map was commissioned from Hall by the Centre for Thomas More Studies in Texas and the designer based the view and the colour scheme on Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg’s map of London from their 1617 Civitates Orbis Terrarum

From his birthplace in Milk Street to the site of his execution, all the sites from the great points of More’s life are here in this map.

The future Lord Chancellor was educated at the school founded by the Hospital Brothers of Saint Anthony, one of the best in the City of London, and when he finished at Oxford returned to London to study law at New Hall and Lincoln’s Inn.

Crosby Place, the house that he bought in 1523 is not far from St Anthony’s School though its surviving remnant was moved brick by brick to Cheyne Walk in 1910 — a site close to More’s Chelsea residence of Beaufort House.

The chapel of Ely Place — town palace of the Bishop of Ely — still survives as St Etheldreda’s, the only mediæval church in London now in use as a Catholic parish.

God’s own Borough of Southwark gets a look in as well, with the Augustinian priory of St Mary Overs (now the Protestant cathedral of Southwark) and the town palace of the bishops of Winchester. Remnants of the great hall of Winchester Palace remains standing to this day.

As is the mapmaker’s privilege, Mr Hall has taken some liberties: in order to fit Lambeth Palace — the residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury (and Primate of All England) he’s shifted it a bit north of its actual spot.

I wish he’d kept the Rose and Globe theatres which he included in his initial sketch for the map — Southwark was the theatre district of its day.

Hall also completed a sketch of Beaufort House as it would have appeared during St Thomas More’s lifetime. The house was demolished in 1740, and today’s Beaufort Street runs the line of the main drive leading up to it.

The Church of All Saints at Chelsea (now known as Chelsea Old Church) is at the bottom of the sketch and is where the More family burial vault is. His severed head is believed to be entombed there to this day.

Lebanon Green

The Connecticut town of Lebanon is known for many things. It is the birthplace of Jonathan Trumbull, the only colonial governor to turn traitor during the American Revolution, as well as of his son the famous painter. The Rev. Eleazar Wheelock founded Moor’s Charity School in the town to teach Native Americans, later moving it to New Hampshire where it became Dartmouth College. Prince Saunders, the Free Black socialite and later Attorney General of the Empire of Haiti, was probably born in Lebanon too.

The town’s most famous feature, however, is its mile-long town green: the longest village common in the world. New England is famous for its town and village greens, originally enclosed land held in common and put to practical use for locals to use as pasture for their animals. Given the size of farms in New England, this purpose quickly faded and the green became a meeting or strolling place. Usually the most important buildings could be found either on or bordering the green: the church, the school, the town hall or court house, and eventually the library.

Part of Lebanon Green is still worked as a hay field, which means this is the last town green in New England that is still in agricultural use. There is even an adjacent vineyard, God bless them.

The green also provoked a recent legal case of some interest. When the Town of Lebanon proposed expanding the public library, located right on the green alongside the Congregationalist church, a problem arose.

Before a permit could be issued, the State of Connecticut required proof of ownership of the land on which the library to be submitted. Alas, no proof could be found, the green having been held in common more or less from the town’s incorporation in 1700.

The last known owners of the green were believed to be the town proprietors listed in 1705, and delineating their heirs or assigns over the dozen or more generations that had passed in the meantime was deemed impossible, or at least strenuous beyond any desirable effort. The town historian estimated there may be as many as 10,000 descendants with a potential claim.

In January 2018, the Town of Lebanon instead requested the court grant them quiet title to three parcels of the town green hosting the library, the town hall, and the town’s public works facilities. In March 2019, their request was granted, and the First Congregational Church likewise took legal action to see it recognised as the owner of the parcel of the green it has occupied for centuries.

Courts have also granted the local historical society conservation authority over 95 per cent of the green — excluding the church, town hall, and library. This means the local histos will have a say on any future use, though the courts declined extending this to the whole of the green. So it looks like the future of Lebanon Green will be safe for some centuries yet.

New England Baroque

Above, the New England baroque of Dunster House, one of the residential colleges at Harvard.

Below, a simple boathouse built at the highwater mark on a New England beach.

Both images (c.f. here & here) from the blog of a twelfth-generation New Englander.

Lady Day 2022

The Feast of the Annunciation — “Lady Day in Lent” to distinguish it from the Assumption which is “Lady Day in Harvest” — was for much of Christendom the first day of the new calendar year and remains one of the traditional Quarter Days of England.

Eleanor Parker — aka “A Clerk of Oxford” — explains here why Lady Day is so important:

It was both the beginning and the end of Christ’s life on earth, the date of his conception at the Annunciation and his death on Good Friday.

To underline the harmony and purpose which, in the eyes of medieval Christians, shaped the divinely-written narrative of the history of the world, 25 March was also said to be the date of other significant events: the eighth day of Creation, the crossing of the Red Sea, the sacrifice of Isaac, and other days linked with or prefiguring the story of the world’s fall and redemption.

The date occurs at a conjunction of solar, lunar, and natural cycles: all these events were understood to have happened in the spring, when life returns to the earth, and at the vernal equinox, once the days begin to grow longer than the nights and light triumphs over the power of darkness.

The last time I wrote about today’s feast I also pointed out it’s also the reason why many English pubs are called ‘The Salutation’.

It was also on this day in 1654 that the English Catholic colonists aboard the Ark and the Dove arrived in the New World and founded the city of Saint Mary in Maryland, as depicted in the painting above.

Thus the Feast of the Annunciation is officially recognised as the State Day of Maryland.

The cause of all this joy is related best in the Gospel according to St Luke:

AND IN THE SIXTH MONTH, the angel Gabriel was sent from God into a city of Galilee, called Nazareth, To a virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David; and the virgin’s name was Mary.

And the angel being come in, said unto her: Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women.

Who having heard, was troubled at his saying, and thought with herself what manner of salutation this should be.

And the angel said to her: Fear not, Mary, for thou hast found grace with God.

Behold thou shalt conceive in thy womb, and shalt bring forth a son; and thou shalt call his name Jesus.

He shall be great, and shall be called the Son of the most High; and the Lord God shall give unto him the throne of David his father; and he shall reign in the house of Jacob for ever. And of his kingdom there shall be no end.

And Mary said to the angel: How shall this be done, because I know not man?

And the angel answering, said to her: The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the most High shall overshadow thee. And therefore also the Holy which shall be born of thee shall be called the Son of God.

And behold thy cousin Elizabeth, she also hath conceived a son in her old age; and this is the sixth month with her that is called barren: Because no word shall be impossible with God.

And Mary said: Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it done to me according to thy word. And the angel departed from her.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories