About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

“Get me ze Führer!”

Stereotypes of Nazi generals in British war films

“The reason for my uniform being a slightly different colour to yours

is never explained.”

The British are, of course, obsessed with the Nazis. There are many reasons for this, amongst which we must include the large number of really quite good war films produced during the 1950s and 1960s.

For some indiscernible reason these movies have the virtue of being eternally rewatchable and many a cloudy Saturday afternoon has been occupied by Sink the Bismarck!, Where Eagles Dare, or The Colditz Story.

The genre also deploys with a remarkable regularity a number of familiar tropes of ze Germans which the above clip from a British comedy sketch programme (introduced to me by the indomitable Jack Smith) aptly mocks.

Nahum Effendi and Cairo’s Lost World

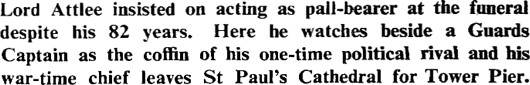

Stumbling across the newspaper clipping above was a sad reminder of a lost world. Taken from the front page of the Manchester Guardian of Monday 29 September 1952, it describes the Egyptian leader General Naguib attending a Yom Kippur service just two months after the coup that overthrew the country’s monarchy. None of the Jewish places of worship in Cairo are known as the “Great Synagogue”, so I presume this must have been the Adly Street Synagogue (Sha’ar Hashamayim).

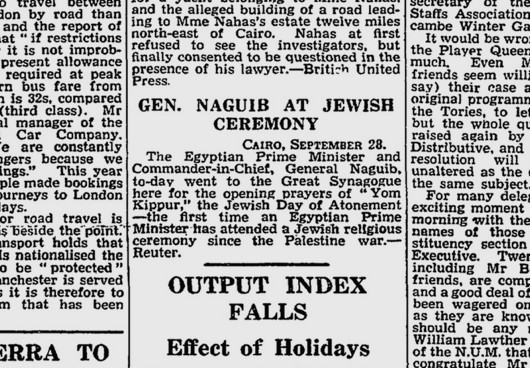

The Chief Rabbi of the Sephardic community in Egypt at the time would have been Senator Rabbi Chaim Nahum Effendi. A creature of the Ottoman world, Rabbi Nahum was born in Smyrna in Anatolia, went to yeshiva in Tiberias on the Sea of Galilee, and finished his secondary education in a French lycée.

After earning a degree in Islamic law in Constantinople, he started his rabbinic studies in Paris while also studying at the Sorbonne’s School of Oriental Languages. Returning to Anatolia he was appointed the Hakham Bashi, or Chief Rabbi, of the Ottoman empire in 1908 and honoured with the title of effendi.

After that empire collapsed, Rabbi Nahum was invited to take up the helm of the Sephardic community in Egypt in 1923. A natural linguist and a gifted scholar, the chief rabbi’s talents were apparent to all, and he was appointed to the Egyptian senate as well as being a founding member of the Royal Academy of the Arabic Language created to standardise Egyptian Arabic.

Rabbi Nahum (front row, third from left) at the foundation of Egypt’s Arabic academy.

The foundation of the State of Israel was a godsend for many Jews but spelled the beginning of the end for Egypt’s community. Zionists were a distinct minority among Egyptian Jews — many of whom were part of Egypt’s (primarily anti-British) nationalist movement — but Israel’s defeat of the Arab League in the 1948 War embarrassed Egypt’s ruling classes and stoked anti-semitism amongst the populace. Violent attacks against Jewish businesses were tolerated by the authorities and went uninvestigated by the police. Unfounded allegations of both Zionism and treason were rife, and discriminatory employment laws were introduced.

The 1952 Revolution did not improve things, as the tolerant but decaying monarchy was replaced by a vigorous but nationalist and pan-Arabist military government. Faced with such continuing depredations, the overwhelming majority of Jewish Egyptians fled — to Israel, Europe, and the United States. Rabbi Nahum eventually died in 1960, by then something of a broken man I imagine.

Cairo was once a thriving cosmopolitan city of Muslims, Christians, and Jews — and many communities of outside origin. The Greeks, who first arrived twenty-seven centuries ago and in 1940 still numbered tens of thousands, have all left. The futurist Marinetti was the most famous of the Italian Egyptians, whose numbers in the 1930s were numerous enough to warrant several branches of the Fascist party. Since the 1952 Revolution they are all gone too. Some Armenians remain, but not many. As for Jews, there are six left in Egypt.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

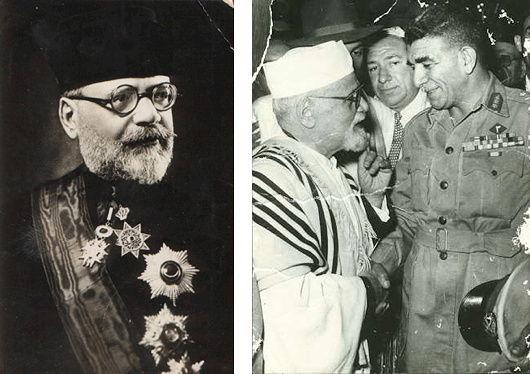

‘The right thing to do is to act virtuously, rather than just talk about doing so’

Welcome to Budapest. Today I do not wish to talk about the persecution of Christians in Europe. The persecution of Christians in Europe operates with sophisticated and refined methods of an intellectual nature. It is undoubtedly unfair, it is discriminatory, sometimes it is even painful; but although it has negative impacts, it is tolerable. It cannot be compared to the brutal physical persecution which our Christian brothers and sisters have to endure in Africa and the Middle East. Today I’d like to say a few words about this form of persecution of Christians. We have gathered here from all over the world in order to find responses to a crisis that for too long has been concealed. We have come from different countries, yet there’s something that links us – the leaders of Christian communities and Christian politicians. We call this the responsibility of the watchman. In the Book of Ezekiel we read that if a watchman sees the enemy approaching and does not sound the alarm, the Lord will hold that watchman accountable for the deaths of those killed as a result of his inaction.

Dear Guests,

A great many times over the course of our history we Hungarians have had to fight to remain Christian and Hungarian. For centuries we fought on our homeland’s southern borders, defending the whole of Christian Europe, while in the twentieth century we were the victims of the communist dictatorship’s persecution of Christians. Here, in this room, there are some people older than me who have experienced first-hand what it means to live as a devout Christian under a despotic regime. For us, therefore, it is today a cruel, absurd joke of fate for us to be once again living our lives as members of a community under siege. For wherever we may live around the world – whether we’re Roman Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox Christians or Copts – we are members of a common body, and of a single, diverse and large community. Our mission is to preserve and protect this community. This responsibility requires us, first of all, to liberate public discourse about the current state of affairs from the shackles of political correctness and human rights incantations which conflate everything with everything else. We are duty-bound to use straightforward language in describing the events that are taking place around us, and to identify the dangers that threaten us. The truth always begins with the statement of facts. Today it is a fact that Christianity is the world’s most persecuted religion. It is a fact that 215 million Christians in 108 countries around the world are suffering some form of persecution. It is a fact that four out of every five people oppressed due to their religion are Christians. It is a fact that in Iraq in 2015 a Christian was killed every five minutes because of their religious belief. It is a fact that we see little coverage of these events in the international press, and it is also a fact that one needs a magnifying glass to find political statements condemning the persecution of Christians. But the world’s attention needs to be drawn to the crimes that have been committed against Christians in recent years. The world should understand that in fact today’s persecutions of Christians foreshadow global processes. The world should understand that the forced expulsion of Christian communities and the tragedies of families and children living in some parts of the Middle East and Africa have a wider significance: in fact they threaten our European values. The world should understand that what is at stake today is nothing less than the future of the European way of life, and of our identity.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We must call the threats we’re facing by their proper names. The greatest danger we face today is the indifferent, apathetic silence of a Europe which denies its Christian roots. However unbelievable it may seem today, the fate of Christians in the Middle East should bring home to Europe that what is happening over there may also happen to us. Europe, however, is forcefully pursuing an immigration policy which results in letting extremists, dangerous extremists, into the territory of the European Union. A group of Europe’s intellectual and political leaders wishes to create a mixed society in Europe which, within just a few generations, will utterly transform the cultural and ethnic composition of our continent – and consequently its Christian identity.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We Hungarians are a Central European people; there aren’t many of us, and we do not have a great many relatives. Our influence, territory, population and army are similarly not significant. We know our place in the ranking of the world’s nations. We are a medium-sized European state, and there are countries much bigger than us which should, as a matter of course, bear a great deal more responsibility than we do. Now, however, we Hungarians are taking a proactive role. There are good reasons for this. I can see – and I know through having met them personally – how many well-intentioned truly Christian politicians there are in Europe. They are not strong enough, however: they work in coalition governments; they are at the mercy of media industries with attitudes very different from theirs; and they have insufficient political strength to act according to their convictions. While Hungary is only a medium-sized European state, it is in a different situation. This is a stable country: the political formation now in office won two-thirds majorities in two consecutive elections; the country has an economic support base which is not enormous, but is stable; and the public’s general attitude is robust. This means that we are in a position to speak up for persecuted Christians. In other words, in such a stable situation, there could be no excuse for Hungarians not taking action and not honouring the obligation rooted in their Christian faith. This is how fate and God have compelled Hungary to take the initiative, regardless of its size. We are proud that for more than a thousand years we have belonged to the great family of Christian peoples. This, too, imposes an obligation on us.

Dear Guests,

For us, Europe is a Christian continent, and this is how we want to keep it. Even though we may not be able to keep all of it Christian, at least we can do so for the segment that God has entrusted to the Hungarian people. Taking this as our starting-point, we have decided to do all we can to help our Christian brothers and sisters outside Europe who are forced to live under persecution. What is interesting about this decision is not the fact that we are seeking to help, but the way we are seeking to help. The solution we settled on has been to take the help we are providing directly to the churches of persecuted Christians. We are not using the channels established earlier, which seek to assist the persecuted as best they can within the framework of international aid. Our view is that the best way to help is to channel resources directly to the churches of persecuted communities. In our view this is how to produce the best results, this is how resources can be used to the full, and this is how there can be a guarantee that such resources are indeed channelled to those who need them. And as we are Christians, we help Christian churches and channel these resources to them. I could also say that we are doing the very opposite of what is customary in Europe today: we declare that trouble should not be brought here, but assistance must be taken to where it is needed.

Dear Friends,

Our approach is that the right thing to do is to act virtuously, rather than just talk about doing so. In this way we avoid doing good things simply in order to burnish our reputation: we avoid doing good things out of calculation, as good deeds must come from the heart, and for the glory of God. Yet now it is my duty to talk about the facts of good deeds. My justification, the reason I am telling you all this, is to prove to us all that politics in Europe is not necessarily helpless in the face of the persecution of Christians. The reason I am talking about some good deeds is that they may serve as an example for others, and may induce others to also perform good deeds. So please consider everything that I say now in this light. In 2016 we set up the Deputy State Secretariat for the Aid of Persecuted Christians, which – in cooperation with churches, non-governmental organisations, the UN, The Hague and the European Parliament – liaises with and provides help for persecuted Christian communities. We listen to local Christian leaders and to what they believe is most important, and then do what we have to. From them I have learnt that the most important thing we can do is provide assistance for them to return home to resettle in their native lands. We Hungarians want Syrian, Iraqi and Nigerian Christians to be able to return as soon as possible to the lands where their ancestors lived for hundreds of years. This is what we call Hungarian solidarity – or, using the words you see behind me: “Hungary helps”. This is why we decided to help rebuild their homes and churches; and thanks to Hungarian Interchurch Aid, in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon we also build community centres. We have launched a special scholarship programme for young people raised in Christian families suffering persecution, and I am pleased to welcome some of those young people here today. I am sure that after their studies in Hungary, when they return to their communities, they will be active, core members of those communities. And we are also working in cooperation with the Pázmány Péter Catholic University on the establishment of a Hungarian-founded university. The Hungarian government has provided aid of 580 million forints for the rebuilding of damaged homes in the Iraqi town of Tesqopa, as a result to which we hope that hundreds of Iraqi Christian families who now live as internal refugees may be able to return to their homes. We likewise support the activities of the Syriac Catholic Church and the Syriac Orthodox Church. I should also mention something which perhaps does not sound particularly special to a foreigner, but, believe me, here in Hungary is unprecedented, and I can’t even remember the last time something like it happened: all parties in the Hungarian National Assembly united to support adoption of a resolution which condemns the persecution of Christians, supports the Government in providing help, condemns the activities of the organisation called Islamic State, and calls upon the International Criminal Court to launch proceedings in response to the persecution, oppression and murder of Christians.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

When we support the return of persecuted Christians to their homelands, the Hungarian people is fulfilling a mission. In addition to what the Esteemed Bishop has outlined, our Fundamental Law constitutionally declares that we Hungarians recognise the role of Christianity in preserving nationhood. And if we recognise this for ourselves, then we also recognise it for other nations; in other words, we want Christian communities returning to Syria, Iraq and Nigeria to become forces for the preservation of their own countries, just as for us Hungarians Christianity is a force for preservation. From here I also urge Europe’s politicians to cast aside politically correct modes of speech and cast aside human rights-induced caution. And I ask them and urge them to do everything within their power for persecuted Christians.

Soli Deo gloria!

Gallen-Kallela at the National Gallery

From November 15 until February of next year, the National Gallery here in London will mark the centenary of Finnish independence with a showing of the works of Akseli Gallen-Kallela. The Finnish painter is best known for his depictions of the Kalevala, the national epic compiled by Lönnrot and an influence on Tolkien.

The National Gallery, however, has focused on bringing together all four versions of Gallen-Kallela’s painting of Lake Keitele (alongside similar works by the artist). As a Swedish-speaking Finn, he signed the painting with his original Swedish name, Axel Waldemar Gallén, which he later Finnicised in 1907.

During Finland’s Civil War, Gallen-Kallela and his son Jorma both took up arms on the side of the Whites, who defended the country from the Soviet-backed Reds. The artist (below) served as adjutant to the regent of the kingdom, Gen Mannerheim, who asked him to design the flag, uniforms, and decorations of the new state. His student Eric O. Ehrström designed a crown for the kingdom, but eventually a republican form of government was decided upon and it wasn’t til the 1980s that a mock-up of the crown was actually crafted.

Having lived in Berlin and Kenya as well as having toured the United States, Gallen-Kallela’s influences were varied but he found the story and scenery of his homeland the most compelling of all. A fitting tribute to Finland in her hundredth year of statehood.

Pimlico Forever – Belgravia Never!

It started with hints and rumours, ill-whispered talk on street corners and tiny little changes, but now it’s all gone too far. You see, Pimlico, the quarter of London in which I dwell, seems under threat of annexation by its far grander but past-its-prime neighbour Belgravia.

It all seemed quite amusing at first. One day I came home to our humble address in Pimlico and was surprised to find the Belgravia Residents Journal amongst our post. Then Tatler nailed its colours to the mast and claimed the Italian coffee shop on our Pimlico street corner is in Belgravia. I went to my bank branch the other day to sort out a minor matter of travel insurance only to notice ‘Belgravia branch’ spelled out in clear concise Helvetica letters. Was that always there? I wondered.

Residents are befuddled and confused for the most part. No one’s quite sure what’s going on. Memories of “Passport to Pimlico” are exchanged — “Blimey! I’m a foreigner!” Concerns that Cambridge Street Kitchen (or at least its Cocktail Cellar) may be in on the move. “Isn’t this place a bit Elizabeth Street?” she said, sipping a Mexcal Negroni.

Landlords in particular are viewed as being suspiciously complicit in Belgravian expansionism. It’s widely assumed that speculators are keen to turn our beautiful whitewashed Pimlico homes (most of them long since divvied into flats) into the embassies, cultural institutes, and the bland organisational headquarters for which Belgravia is known.

“Do you think we’ll get some embassies after we join Belgravia?” one resident asks. Another points out we already host three: Lithuania, Albania, and Mauritania. “Perhaps we could get Sweden. Do you think we could get Sweden?” No one seems to know.

Some pooh-pooh the entire idea as hyped-up nonsense. “What on earth would Belgravia want from us here in Pimlico? Her Majesty’s Passport Office? The Queen Mother Sports Centre? The Catholic Bishops Conference? The flippin’ UK Statistics Authority?” (I admit, I had no idea the UK Statistics Authority is based here in Pimlico.)

Others prepare for collaboration. “We’ve always considered this Lower Belgravia,” Dr O’Donnell says with a wry smile.

Still, there is talk of resistance. Estate agents have reportedly been threatened with the use of force by mysterious figures in black cagoules. Suggestions of pre-emptive action, or recourse to the Court of Justice in Strasbourg. Should we strike first? Enclaves of Pimlico the other side of Buckingham Palace Road, like the pool hall in Ebury Square, could be used as springboards for a more active approach. The Filipino ladies in the Padre Pio shop on Vauxhall Bridge Road seem blissfully unaffected.

Confusion reigns, uncertainty is rampant, no one knows what the future holds.

Hoarding has commenced and local shops are quickly selling out of useful products (bog roll, Pringles, gin, etc.).

From St George’s Square to Victoria Station, fear grips the streets. At least its stopped people talking about Brexit.

The ‘Other Modern’ in Portugal

Guarda, Portugal; 1939–1942

[A] core aspiration can be discerned that runs through the entire [architectural] output of the “Estado Novo”, particularly from the second half of the 1930s. It is a catchphrase, never defined with absolute clarity and therefore tested by approximation, trial and error: the demand for a national modern style, a construction style that was at the same time contemporary and suited to the locality and/or specificity of the country. This agenda accommodated various formulations, depending on the evolution of the regime itself, the type of public building in question, the place for which it was intended, the profile of the people responsible for its appraisal and the margin granted to the architect-designer. […]

Salazarism never upheld anachronism or the practice of an archaeological type of architecture. It did not reject modernity entirely, but disliked disaggregating, standardising, stateless foreignness, embodied in its view by the architectural abstractionist internationalism (dubbed “boxes”). An alternative modernity was thus aspired to and achieved; far from being an exclusive diktat of the state, this idea of an alternative modernity pervaded the discourses of the timid specialist press, the opinions generally expressed by the civil society and the dilemmas of the architects themselves.

RIHA Journal 133, 15 July 2016

See also: The Other Modern

Lisbon

One of the finest cities I have had the privilege of visiting, only lightly touched by the grim hand of modernism.

F.C. Kolbe and the Tulbagh Drostdy

the Tulbagh Drostdy

Poet, Polemicist, Polymath, and Priest

Relic and emblem of a storied past.

Thrice happy they whose lines in thee are cast

Thy records summon all in thy embrace

To emulate the virtues of the race.

Thy stately halls of courtly manners tell,

Where only Ladies Bountiful should dwell.

Thy solid frame is pledge of future glory,

And links our doings with our country’s story.

Work on the Drostdy (magistrate’s house) at Tulbagh in the Western Cape began late in 1804 but progressed rather slowly and expensively. This is probably because — after construction commenced — the plans by Bletterman, the landdrost at Stellenbosch, were torn up by the architect Louis Michel Thibault and replaced by his own design.

This meant part of the work already completed had to be demolished and re-done, which Bletterman only went along with assuming Thibault’s plan had the approval of the Batavian Republic’s governor of the Cape, Jan Willem Janssens. As it happens, they did not, and when Bletterman found out he was none too pleased.

Francis Masey, a partner at Herbert Baker’s firm, noted that “[w]hilst it proved to be the last building begun upon Dutch soil in South Africa, it was destined to be the first completed upon the passing of the Cape into the hands of the British.”

This  brief ode was written by Frederick Charles Kolbe (right) in 1909. The great-great-grandson of the magistrate (or landdrost) at Stellenbosch, F.C. Kolbe was the son of a Congregational missionary in Paarl who studied law at the Inner Temple in London. There, in 1876, he was received into the Catholic Church and continued on to study in Rome where he was ordained a priest in 1882.

brief ode was written by Frederick Charles Kolbe (right) in 1909. The great-great-grandson of the magistrate (or landdrost) at Stellenbosch, F.C. Kolbe was the son of a Congregational missionary in Paarl who studied law at the Inner Temple in London. There, in 1876, he was received into the Catholic Church and continued on to study in Rome where he was ordained a priest in 1882.

While his poetry was tended towards the middling, Kolbe was a distinctive polymath. In addition to catechetical writings, he published a number of works on Shakespeare, and lectured on Socrates not long after his 1882 return to the Cape. Eventually he was appointed Reader in Aesthetics at the University of Cape Town.

Kolbe also wrote a Catholic criticism of the 1926 book Holism and Evolution by the statesman General Smuts. (Not many people realise that the word ‘holistic’ was donated to the English language by a son of Stellenbosch.) The general and the priest had corresponded as early as 1915 when Smuts was Minister for Defence, and Smuts was so taken with Kolbe’s critique that he wrote a foreword to a later edition of it.

In a 1935 letter to “Dr. Kolbe”, the General wrote:

Although I am not acquainted with the Catholic prayers, I am deeply versed in the Psalms of the Old Testament, which seem to me the greatest and noblest outpourings of the human spirit ever put into language. The inexpressible finds expression there. Emotions almost too deep for utterance somehow find an outlet there. …

I also agree with you as to the nobility of the language which Catholic Christianity has evolved. What could match the beauty of De Imitatione Christi? Somehow it breathes a spirit which is beyond all language. It is curious how in such a case the human soul sets on fire its own earthly vesture, and language becomes a blaze of glory…

From Smuts’ letters to others we know that he actually read more works by Kolbe, in particular his Up the slopes of Mount Sion: or, A progress from Puritanism to Catholicism.

Disputation and discussion were also among Kolbe’s talents. He used the pages of South Africa’s Catholic Magazine to counter the accusations of what he called a “narrow clique” of anti-Romish ministers of the Dutch Reformed Church.

One of Kolbe’s most lasting legacies was the effect of his writing on the young Afrikaner philosopher Marthinus Versfeld (1909–1995) who converted to Catholicism under the late Monsignor’s influence. (Kolbe had died in 1936.) Versfeld’s familiarity with Augustine and Aquinas helped him launch intellectual attacks against the so-called “Christian-national” thinking behind apartheid, particularly in his first book Oor gode en afgode (“Of Gods and Idols”, 1948 & republished 2010).

Kolbe, according to Versfeld, “lived out a certain apprehension of the presence of the universal in the particular, just as Newman lived out his vision of the Catholic Church in the material of English circumstances.”

An Afrikaner Newman, perhaps? Worth reading more about.

The French Way of War

I’ve  been reading Lartéguy recently so was intrigued to hear of another French writer formed by his military experience, Pierre Schoendoerffer (right).

been reading Lartéguy recently so was intrigued to hear of another French writer formed by his military experience, Pierre Schoendoerffer (right).

In a tweet, the cigarette-smoking Helen Andrews shared an article called What a 1963 Novel Tells Us About the French Army, Mission Command, and the Romance of the Indochina War.

I dislike the romanticism surrounding the magnificent losers vs. ugly victors dichotomy – a magnificent victory is infinitely preferably to both. Hence why my natural Jacobite sympathies are highly qualified by complete and utter disdain for Charlie’s unwillingness to see the task through. (An easy judgement when made from centuries of hindsight, I’ll concede.)

Anyhow, I sent the article to The Major and he proffered this reply:

I was going to say something snide about the French army but to be quite honest I have thought for some time that it is rather better than ours [Ed.: the British]. Their officers are tougher, harder, and more professional than ours – those I encountered professionally certainly were. They are also not infected by the political correctness which is wrecking/has wrecked our army (among other factors).

The distinction between the colonial army and the large conscript army at home is valid. It was the conscript army which was defeated in 1870, 1914, and 1940… not the colonial army to which the modern French army now looks.

It is also true that the US Army don’t do Mission Command well. The Marines on the other hand…

Meanwhile back in the States the prolific Ken Burns has done an eighteen-hour documentary on the Vietnam conflict which allegedly ignores all the scholarly input of the past two decades. Nevermind, we just regret it won’t feature the late great Shelby Foote, who (in Burns’s ‘The Civil War’) spoke with such assurance you imagined he was there.

Urgent Action for Catholic Free Schools

Since the Free Schools programme was introduced in 2010 (allowing parents and other groups outside the state to start and run schools) more than 400 new schools have been approved for opening, providing over 230,000 new school places across the country.

During the Coalition, though, the Liberal Democrats insisted on putting a 50% cap on admissions for free schools that are faith-based. Because Catholic schools are not allowed to reject Catholics simply because of their faith, the policy’s only real effect has been to entirely prevent any Catholic free schools from opening, while failing to do anything about the integration of religious or ethnic minorities.

The Prime Minister has rightly pointed out that “Catholic schools are more ethnically diverse than other faith schools, more likely to be located in deprived communities, more likely to be rated Good or Outstanding by Ofsted, and there is growing demand for them.”

As the British population has increased, the shortage of new Catholic school places has only become more alarming. When the Prime Minister announced the cap would be dropped, Catholic dioceses sprang into action making plans for Catholic free schools. Some even bought sites, one being located next to a hospital to educate the children of immigrant nurses and medical staff who’ve come from Catholic countries to staff our NHS.

But right now Catholic free schools are under threat. Despite a solemn commitment in the Conservative manifesto, Education Secretary Justine Greening is believed to be inclined to make a U-turn and keep the admissions cap which acts as a ban on Catholic free schools.

I ask that you email your Member of Parliament right now, asking him or her to contact the Education Secretary and request that this manifesto commitment be honoured and the faith-based admissions cap be scrapped. A decision is likely to be made very shortly, so time is of the essence.

Many thanks,

Andrew Cusack

To find your MP’s contact details, put in your postcode at this link.

As one of your constituents I am writing to ask you to help scrap the faith-based admissions cap for free schools.

The Government is right to be concerned about the integration of religious and ethnic minorities. This policy, however, began with the best of intentions but has been proven a complete and utter failure. Exhaustive research has proved the cap is completely ineffective towards its stated aim.

Canon law forbids Catholic schools from rejecting fellow Catholics purely on the basis of their faith, which the admissions cap requires. The cap’s only real effect has been to prevent the foundation of Catholic free schools, despite the dire need for quality school places amongst the poorest in our communities.

Catholic schools, meanwhile, are profoundly diverse and educate the children of many faiths and of none. More than 26,000 Muslim pupils are currently receiving education in Catholic schools. One in seven ethnic minority pupils in England & Wales attend a Catholic school, including more than one in five black children.

Across the board, Catholic schools educate 21% more pupils from ethnic minority backgrounds compared to other schools, and these pupils in Catholic secondary schools perform better at GCSE than the national average. These schools also have a record second to none in looking after the most disadvantaged in our society. 16.5 % of pupils in Catholic secondary schools live in the most deprived areas, compared to 11.3% nationally.

Before the election, the Conservative government openly stated its intention to scrap the faith-based admissions cap, which requires only the Education Secretary’s signature to be enacted. The Conservative party then went to the nation in a general election and included this promise in its manifesto.

I ask that, as my MP, you urgently contact Justine Greening MP, the Secretary of State for Education, and ask her to honour the manifesto commitment to scrap the faith-based admissions cap.

Yours,

NAME

FULL POSTAL ADDRESS

Justice in the Royal Gallery

One of the great triumphs of Magna Carta was the assertion of the right of those accused of crimes to trial by one’s peers, or per legale judicium parium suorum if you insist on the Latin. For commoners this meant trial by other commoners, but for peers it meant just that: trial by other peers of the realm. It was a bit murkier for peeresses, though after the conviction for witchcraft of Eleanor, Duchess of Gloucester, (sentence: banishment to the Isle of Man) statute was passed including them in the judicial privilege of peerage.

Thanks to the ’15 and the ’45, there were a number of trials in the House of Lords in the eighteenth century, including that of the Catholic martyr Earl of Derwentwater. The whole of the nineteenth century, however, witnessed but one: the 7th Earl of Cardigan was acquitted of duelling by a jury of 120 peers. In 1901 the 2nd Earl Russell was found guilty of bigamy, and the last ever trial came in 1935 when the 26th Baron de Clifford was found not guilty of manslaughter.

Cardigan’s trial was in the temporary Lords chamber while the last two trials took place in the Royal Gallery of the Palace of Westminster (central to current debates over renovation plans). For Cardigan’s trial the Lord Chief Justice of the Queen’s Bench was appointed Lord High Steward for the occasion, while for the final two the Lord Chancellor was likewise appointed to the role in order to be presiding judge with the Attorney General prosecuting the case.

The Royal Gallery is primarily used for the State Opening of Parliament (as above) and for the occasional address to both Houses of Parliament when important figures are invited to do so. De Gaulle was famously invited to speak here to both houses rather than in the larger Westminster Hall. It is thought that this is because the walls of the Royal Gallery feature two large murals, one of the Battle of Trafalgar, the other of the Battle of Waterloo – both British victories over the French.

The most famous trial in the Royal Gallery was fictional. In the 1949 Ealing comedy “Kind Hearts and Coronets”, the 10th Duke of Chalfont is tried for the one murder in the film’s plotline he didn’t actually commit. Ealing Studios did a mock-up of the chamber for the occasion (above), which compares reasonably accurately with the Royal Gallery as set up for the Baron de Clifford’s trial in 1936 (below).

The Lords, however, were uncomfortable with exercising this judicial function and passed a bill to abolish the privilege in 1937. The Commons, facing more serious tasks, declined to give it any attention. In 1948, the Criminal Justice Act abolished trials of peers in the House of Lords, along with penal servitude, hard labour, and whipping.

Hougaard Malan

South African Landscape Photographer

When I lived in South Africa I began to understand the deficiencies of photography. The scenery in which one we had the privilege of acting out “the foolish deeds of the theatre of our day” (as Mr Mbeki put it in one of his better speeches) was stunning, but on the few occasions I bothered to put my Leica to good use the results were disappointing. You’d look at a photograph that was admittedly beautiful but still think to yourself “But in real life it was a thousand times more beautiful than that!” Needless to say, my own lack of skill as a photographer is the most obvious cause.

Hougaard Malan, meanwhile, is one of the few photographers who manages to almost, nearly capture the beauty of the South African landscape. In each and every shot — and some of these places are well known to me — the scale and drama of the location shines forth.

“Growing up, my grandmother always gave me illustrated encyclopedias and books about earth’s natural history that were filled with fantastic landscape images,” Mnr Malan says. “I spent many afternoons paging through these books and marvelling at nature’s beauty. Few things in life made me feel more alive than a landscape that engaged all my senses – seeing the rhythmic rolling of waves in a bay, smelling the coastal flora, hearing and feeling the ocean crash against the cliffs and then tasting the salt in the air.”

Mnr Malan’s website can be found here but here is just a small sampling of the photographs of southern Africa and well beyond which this talented man has taken.

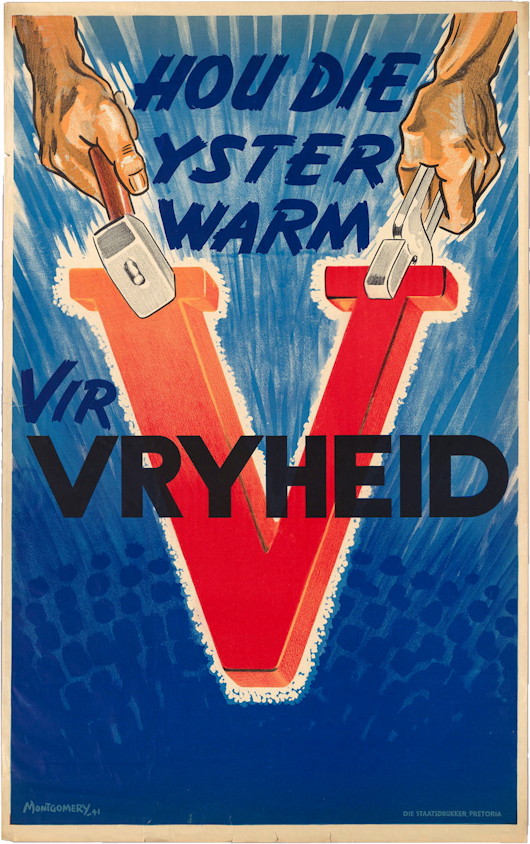

V for Victory (en Vryheid)

The twenty-second letter of the alphabet became a powerful symbol during the Second World War — ‘V’ for Victory, and all that. Even the Morse code for the letter — dot-dot-dot-dash — became useful, echoing as it did the famous four-note motif from Beethoven’s fifth symphony.

In South Africa, however, the two main languages were English and Afrikaans, and the Afrikaans word for victory, oorwinning, does not start with a ‘V’. Instead the letter was used to stand for vryheid, or freedom, just as in Belgium it stood for both victoire for the Walloons and vrijheid for the Flemings.

When the Second World War started Prime Minister Hertzog announced a policy of neutrality, only to be toppled as premier by his deputy and ally Smuts who brought South Africa into the war a few days later than Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

This wartime propaganda poster, produced by the Staatsdrukker in Pretoria, urges South Africans to ‘keep the iron hot for freedom’. The country’s industrial production made a valuable contribution to the war effort in addition to the volunteer manpower of the Union Defence Force and, perhaps most importantly, the gold that came from the Witwatersrand mines.

From Realm to Republic

South Africa’s transition from a monarchy to a republic coincided with a change of currency. Out went the old South African pound (with its shillings and pence) and in came the decimilised rand.

Luckily the republican government had the good taste to commission George Kruger Gray, responsible for the country’s most beautiful coinage, to design the new coins. HM the Queen was replaced by old Jan van Riebeeck, and the country’s arms were deprived of their crown.

Champagne and the World

Champagne can provoke a great deal of philosophy. I’ve often said that champagne and the Catholic faith are the only two universally applicable things in the universe – appropriate for births, deaths, good times and bad, early, late, or a mundane afternoon.

Iain Martin has a brief but excellent piece ‘On Wine’ discussing Churchill’s drinking habits, and wondering whether he really was permanently pissed during the war (unlike the teetotal vegetarian Mr Hitler).

Interesting in itself, but Mr Martin relates a trip to Épernay where he blind tastes a Margaux from 1873. By that time it should have tasted like vinegar but instead it was “beautifully balances and perfectly drinkable”.

Looked after carefully, not shaken about or disturbed unnecessarily, it evolved and endured. It retained its essential characteristics, giving pleasure to later generations. If only we nurtured political institutions and good government according to the same principle.

Nothing could better show the essence of a sound worldview.

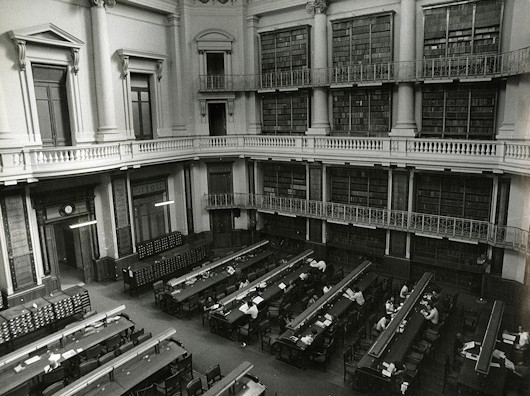

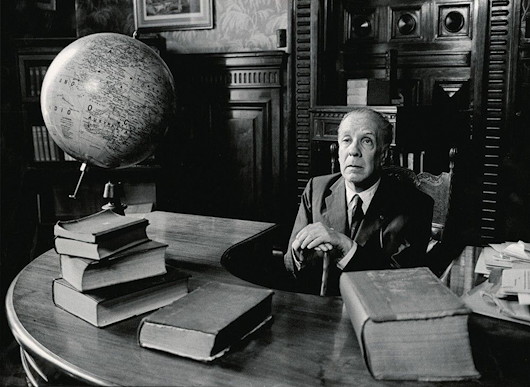

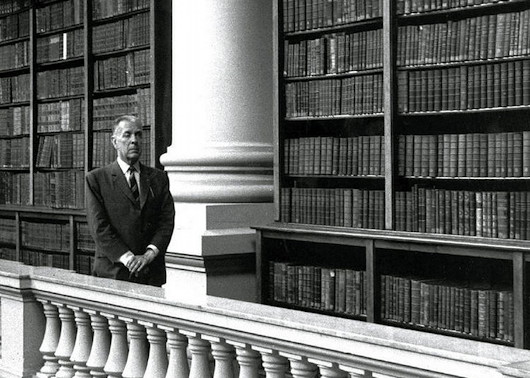

Borges’s Biblioteca

The old National Library on Calle Mexico in Buenos Aires

The intellectual Alberto Manguel grew up amidst the library of the Argentine diplomatic compound in Tel Aviv, as he recalls in this piece for Britain’s strangely underappreciated Literary Review.

At the end of 2015 Señor Manguel was appointed director of Argentina’s National Library, taking up his position in the middle of last year. In this role he steps into the shoes of Jorge Luis Borges who led the institution from 1955 until he resigned upon Peron’s return in 1973.

Returning to the ‘Queen of the Plata’ after a long career in exile was not a simple affair. As Señor Manguel writes:

The city, of course, was different. I found it difficult to look at the actual streets and houses without remembering the ghosts of what had been there before, or what I imagined had been there before. Buenos Aires felt now like one of those places seen in dreams, the geography of which you think you know but which keeps changing or drifting away as you try to make your way through it.

The National Library I had known during my adolescence was a different one. It stood on Mexico Street in the colonial neighbourhood of Montserrat. The building was an elegant 19th-century palazzo originally built to house the state lottery but almost immediately converted into a library. Borges had kept his office there when he was appointed director in 1955, when ‘God’s irony’, he said, had granted him in a single stroke ‘the books and the night’. Borges was the fourth blind director of the library, a curse I’m intent on avoiding. It was to this building, during the 1960s, that I used to go to meet Borges after school and walk him back to his flat, where I would read stories by Kipling, Henry James and Robert Louis Stevenson to him. After he became blind, Borges decided not to write anything except verse, which he could compose in his head and then dictate. But some ten years later he went back on his resolution and decided to try his hand again at a few new stories. Before starting, Borges wanted to study how the great masters had gone about writing their own. The result was two of his best collections, Doctor Brodie’s Report and The Book of Sand.

The library I discovered half a century later was lodged in a gigantic tower designed in the brutalist style of the 1960s. Borges, passing his hands over the architect’s model, dismissed it as ‘a hideous sewing machine’. The building is supposed to represent a book lying on a tall cement table, but people call it the UFO, an alien thing landed among pretty gardens and blue jacaranda trees. […]

In my adolescence, I tried to write, no doubt under the influence of Borges, a few fantastical stories, now fortunately lost. One of them was about an unbearable know-it-all to whom the devil, in exchange for I don’t recall what, entrusted the overseeing of the world. Suddenly, this oaf realises that he has to deal with everything at once, from the rising of the sun to the turning of every page of every book, and the falling of every leaf, and the coursing of every drop of blood in every vein, and he is crushed by the inconceivable immensity of the task.

I had wanted to try to put my ideas about reading and libraries into action ever since I received my first books. Now I have got my wish with a vengeance. I have never in my life done anything as demanding and overwhelming as directing the National Library of Argentina. I have become, from one day to the next, an accountant, technician, lawyer, architect, electrician, psychologist, diplomat, sociologist, specialist on union politics, technocrat, cultural programmer and, of course, librarian. I hope that, time and Argentinian politics permitting, I’ll be able to start a few things that may allow us to have, in the not too distant future, a national library we can be proud of.

First Gypsy Woman Martyr is Beatified

Emilia Fernández Rodríguez was killed during Spanish Civil War

The Catholic Church has beatified its first gypsy martyr in a ceremony in the Spanish city of Almería on the southern Mediterranean coast. Emilia Fernández Rodríguez, also known as “La canastera” (the basket-weaver), was one of 115 martyrs murdered in odium fidei by anti-Catholic militants during the Spanish Civil War.

The beatification ceremony took place in the city’s conference centre attended by over 5,000 people, including twenty-one bishops and four cardinals.

In 1938, Blessed Emilia Fernández was a poor gypsy woman living with her husband in Tíjola and surviving by basket weaving when the Republican forces occupied the town, shutting its church, and conscripting its menfolk. Emilia’s husband Juan with her help feigned blindness to escape conscription but was discovered and the couple were imprisoned separately.

Arriving at the women’s prison in Gachas-Colorás, Blessed Emilia was already pregnant and was jailed alongside many other practicing Catholic women who had refused to abjure their faith. Illiterate and never having been catechised despite being baptised, Blessed Emilia was taught how to pray the Rosary by another inmate. Her devotion to this Marian prayer and meditation attracted the ire of the prison authorities who threw her into solitary confinement for refusing to reveal which of her fellow inmates had catechised her.

After the birth of her baby girl, Ángeles, Blessed Emilia died as a result of her weakened condition from malnutrition and the appalling conditions of her isolation. Just twenty-three years old, her body was dumped into a common grave in Almería.

South Africa in the Old Days

This historical film about the early days of the Cape was probably produced for the van Riebeeck tercentenary festival of 1952.

The clip here covers the days of Governor Willem Adriaan van der Stel, depicting them as carefree days of harmony and merriment in South Africa – in contrast to Europe where war and persecution reigned. Doubtless this was how the apartheid government sought to portray South Africa at the time: a haven of peace and prosperity in contrast to a Europe still recovering from war, with half the continent now under the Soviet boot.

Simplistic propaganda of course, but the film conveys a certain charm regardless, as does almost every depiction of the Cape before the British. The sight of geese flocking before an old Cape Dutch homestead (circa 7:00) never fails to touch the Cusackian heart…

Gandhi in Fascist Rome

Returning home to India from the second London Round Table Conference in 1931, the genial Indian nationalist leader Mr Gandhi decided to call in on that most ancient, venerable, and eternal city of Rome. He accepted the invitation to stay as a guest of the aviation pioneer (and later fascist senator) General Maurizio Moris and, purporting to be of something of a spiritual aficianado, hoped to be granted an audience with the Holy Father. Gandhi had by then adopted an unwavering costume of sandals and homespun which was thought unsuitable for the papal court, and Pius XI — in many ways a wise man — decided against the Indian’s request. Mussolini, however, was less fussy and granted the “Mahatma” a private audience on the very evening of his arrival.

In some ways they were similar: Gandhi and Mussolini shared a gift for the theatrical as well as an unshakeable self-belief. Mussolini fancied himself the leader of his people, despite the King above him, and Gandhi thought likewise of himself despite the entire apparatus of the Raj standing apart from and above him. Gandhi, however, never stooped to the level of the buffoon, unlike his Italian friend, and (even after independence) wisely abjured himself from ever taking on the actual responsibilities of government and state office. (more…)

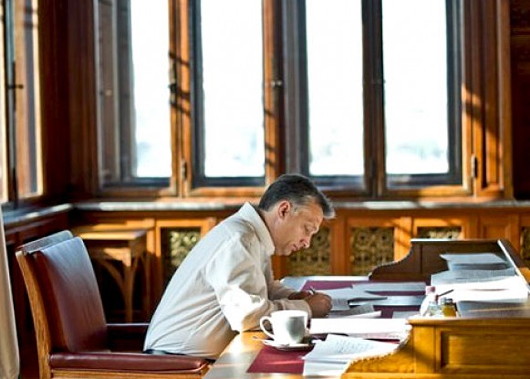

The Earl Attlee

At Chartwell one weekend in Churchill’s presence, Sir John Rodgers made the mistake of referring to Clement Attlee, wartime deputy prime minister and postwar prime minister, as “silly old Attlee”. Churchill was having none of it.

“Mr Attlee is a great patriot,” he said. “Don’t you dare call him ‘silly old Attlee’ at Chartwell or you won’t be invited again.”

The leader of the Conservative party and the leader of the Labour party were obvious political rivals but developed a great bond by their shared experience in the cross-party War Cabinet.

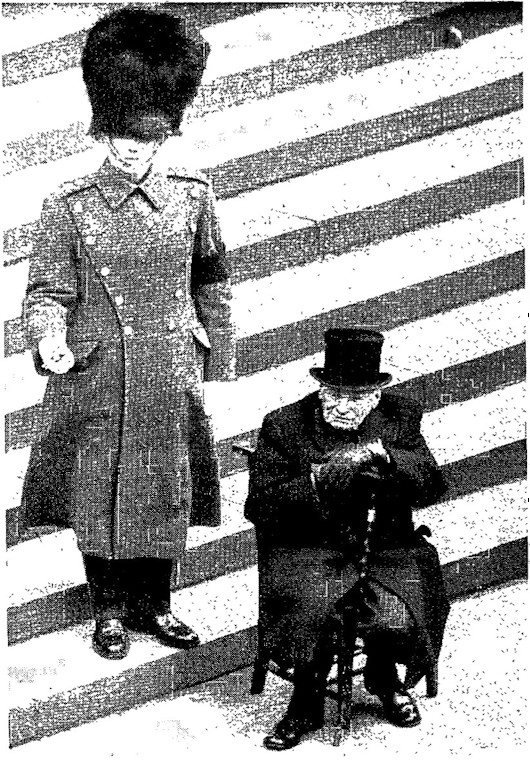

En route to a dinner party the other night I happened to run into Attlee’s greatgrandson (an old friend) on the upper deck of the 414 bus. It reminded me of this photo (above) printed in the Observer. When the great bulldog went on to his eternal reward in 1965, the incredibly frail Earl Attlee insisted on attending the state funeral in St Paul’s Cathedral. Though younger, he only managed to outlive him by two years.

Attlee had been raised to the House of Lords (where he spoke against Britain joining the EEC) in 1956 and, rather appropriately, he chose as the motto for his coat of arms Labor vincit omnia — Labour conquers all.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories