About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

A Chapel in Bavaria

The Friedhofskapelle, or cemetery chapel, in Herrsching on the Ammersee in Upper Bavaria is a wonderful model of a small church or chapel.

It was designed in 1926 by Roderich Fick, who was a disciple of Theodor Fischer. Herr Fick participated in an expedition to traverse Greenland and joined the German colonial service in Cameroon, after the war moving to Herrsching in 1920.

During the Third Reich he was tasked with redesigning the city of Linz where Hitler had spent his childhood, but the dictator found Fick’s plans somewhat restrained, while Martin Bormann was constantly picking fights with the architect. The dominant style of the regime did not align with Fick’s preference for humble, unpretentious tradition in building design.

After the war he was sentenced to aid in the reconstruction of Munich, and also helped restore the magnificent Town Hall of Augsburg.

The Week

Our monthly Mass in St Wilfrid’s Chapel for the Order of Malta Volunteers. In the summer we sometimes fit about thirty people into the chapel but in the winter months volunteers tend to hibernate more. It being Lent has made everyone that little bit more morose and less keen on activity.

In accordance with custom since time immemorial, we all head to the Bunch of Grapes for drinks afterwards. Many are off the sauce as a Lenten penance, so miserable lime-and-sodas are aplenty. It is revealed that Rosie M. is an avid drummer. Didn’t you see the massive drum set when you walked into the farmhouse? No, because it was only about three seconds after I came through the door that you were already hurling insults. (Torturing Cusack seems to be a particular vocation amongst two-fifths of the M. sisters.)

The pub has suffered several improvements lately which occasioned its closing for several weeks. For a time refugees poured off to the Horrorglass or, my preference, the Star Tavern just a few minutes’ walk away in Belgravia. But return to the B.O.G. we must. It is now a little shinier, and some of the seating less convenient, but other aspects seem better (the lighting fixtures, I suppose). The staff, thank God, are exactly the same.

On Sunday afternoons there is now a gentleman who sits there and does the crossword and sometimes makes the occasional remark if he disapproves of the turn our conversation has gone. We must endeavour to provoke him – we were here first, after all.

A book launch at the Society of Antiquaries. I arrive at the same time as one of Queen Victoria’s great-granddaughters who inexplicably has a German accent despite having moved to this country just after the war when she was five or six years old. We do the washing-up together at a soup kitchen every week and for some reason we break out into laughter whenever we see one another. Nikolaus turns up so I introduce them and off they go. You are from Leipzig? I am from Coburg!

While cold outside it is of course too warm indoors and nary a window is opened. Nae bother. Another glass of white, please. Across the room I see The Young Major chatting merrily to The Army Doctor, probably conspiring against me. Liam and I talk about Athlone during the Civil War. Serenhedd gives no hints as to who will be the next provost of Oriel. Afterwards, a handful of us end up at what is allegedly the Queen’s favourite restaurant, off Berkeley Square.

To Marylebone for a supper with the local Conservative ward in Dorset Square. I have been attempting to help out with the party since I was a teenager at uni in Scotland, where our association was led by the ever-capable Stuart Paterson. (When Stuart did a year abroad in Germany, I had him write a ‘Bonn Voyage’ column for the student newspaper I edited.)

Campaigning in Westminster North last year, I came across a gang of rastas sitting on their front step enjoying the sunshine and drinking Lambrini. Naturally I engaged these gentlemen in conversation, apologising for my interruption of the beautiful afternoon and enquiring as to their voting intentions. The leader of the pack said he would be more than happy to vote Conservative but asked what reward they might receive for this virtuous act.

“Who knows, they might give you a peerage,” I suggested, careful not to cause an inducement that might transgress the Political Parties, Elections, and Referendums Act 2000. “OK OK – but Lord isn’t good enough,” our chief said in a thick West Indian accent. “I want to be a duke!” (I’d prefer a viscountcy myself, but I couldn’t help admire his vision.) “Yes, but if you are made a duke, what will you be duke of?” Our Jamaican friend raised his cheap bottle to the sky and said “DUKE OF LAMBRINI!” I insisted I couldn’t make any promises but that I would have a word with the Prime Minister, but only if we won the seat.

Given that we often associate an interest in politics with tiresome boors, one is always slightly surprised how fun and interesting most of the people you meet at Conservative party events are, and Wednesday was no exception. In addition to new people there were some good old faces as well (Gudmund, Pritchett, and of course E.M. who got us there in the first place.) I apologised to Mark Field MP that I was no longer his constituent, having moved from Pimlico to Waterloo, but my MP there is Kate Hoey who is a Brexit-voting pro-foxhunting Labourite from County Antrim, beloved of many Tories.

To Spitalfields for a drinks party in Mariga Guinness’s old townhouse now inhabited by (amongst others) a black Labrador named Ralphie. The evening was a tribute to Mariga organised by the London chapter of the Irish Georgian Society. In addition to founding the Society in 1958 with her husband Desmond Guinness, she was also almost single-handedly responsible for the revival of run-down neglected old crime-ridden Spitalfields, whose Georgian houses with their particular style are now highly prized.

The historian Dan Cruickshank was on hand to elaborate on how this came about and Mariga’s skillful charm in wooing councillors, politicians, neighbours, and future residents and to tell us of the wonderful parties that were held in these very rooms.

In addition to its history and its architecture, the neighbourhood boasts one of the finest London-centric blogs in existence, the eternally interesting Spitalfields Life, written by the Gentle Author. I tried to prod one of our hosts into revealing the identity of the Gentle Author, who alas couldn’t make it that evening, but a sturdy silence was maintained and the Author’s anonymity safeguarded. Secrets are safe in Spitalfields.

Disgracefully I had never been to St Mary’s Church in Cadogan Street, Chelsea, until this day, and it took the funeral of dear Ann’s sister to get me there. It is a beautiful church, the sanctuary curiously quite English, especially when one considers it was designed by Bentley who was responsible for the Byzanto-Edwardian cathedral church at Westminster we love so well. The church was founded in the 1810s by the Abbé Jean Voyaux de Franous, who took on the spiritual care of the Catholic pensioners at the Royal Hospital Chelsea nearby.

The brief eulogy after Mass pointed out that Ena-Maria was not known for her punctuality. Once arriving at a house in northern France, having driven from climes further south, she was greeted by her hostess and apologised deeply for turning up two hours later. “My dear Ena-Maria!” came the reply, “You are not two hours late, you are twenty-six hours late!”

Besides anecdotes of the departed, the conversation at the reception following turned to a variety of subjects: Brexit, the Hapsburgs, Romy Schneider, that sort of thing.

It is already a whole year since Sharon Jennings shuffled off this mortal coil. A whole gang of us, perhaps a dozen or so – family, friends, clergy, and dogs – gathered at her graveside to pray the Rosary and say the Vespers of the Dead. The sun hung low in the sky, peeking occasionally through the clouds to illuminate the lump of earth where Sharon’s remains now await the end of time and the raising of the dead.

The next day a Year’s Mind Mass was offered for the repose of her soul in the St George’s Chapel of Westminster Cathedral, where the statue of Our Lady of Walsingham that she lovingly restored is displayed. In his homily, Canon Tuckwell mentioned that Sharon was “a woman of surprises”, one of which was the revelation at her death that her up-til-then well-hidden middle name was Anona.

My last memory is of visiting her in hospital. “What’s the prognosis then?” “Death, guy.” (She called everyone ‘guy’). Soon enough she was onto her favourite subject of who had been awful lately and great kindnesses and which priest was being insufferable and did-you-hear-about-what’s-her-name and that sodding you-know-who.

Sharon was a mother, wife, playwright, poet, artist, writer, gin-drinker, and friend and dearly missed by all who knew her. She was also a collector of people – waifs and strays of many kinds – and it was testament to her continual kindness, generosity, and hospitality that so many people have taken the time to gather and pray for the repose of her soul a year after her death. May her soul and the souls of all the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, rest in peace.

City Hall

These images of City Hall show the superb skill and eye for detail of the architectural photographer John Bartelstone — a licensed architect in his own right — and date from the completion of the most recent set of renovations in 2015.

Trad Flag

When a cardinal dies his galero is suspended aloft above his tomb to slowly rot and wither away, thus showing the eventual fate of all earthly things. Unlike galeros, the construction and manufacture of flags has “advanced” much in the past century in the sense that they are now made of virtually indestructible materials. This renders them useful for long-term outdoor display but is somewhat lacking in texture, feel, and look.

Earlier flags were made of materials that allowed them to grow old gracefully adding dignity with each passing year, whereas today more often than not they are printed on synthetics. Sewn flags are still available, if at slightly greater cost, and are a good way to keep things smart.

I love a good trad flag though, and Oriel College Boat Club – a festive institution well known for the quality of both its rowing and its conviviality – has a perfect example of one (above and below). From my admittedly unexpert eye, I’d say it’s printed on cotton. Perhaps others know more.

A handsome banner that I dare say outsmarts any of its neighbours in the row of boathouses along the Isis.

Recent Reads

Few things are more enjoyable then a good old-fashioned take-down, and philosopher John Gray delivers the goods with this wonderful review of the latest book by the psychologist and “popular science” writer Steven Pinker, a “feeble sermon for rattled liberals”.

Meanwhile, the inestimable Pee Eee Gee – Pascal-Emanuel Gobry – argues that France’s reigning concept of laïcité is of much more recent vintage then its proponents claims.

The 1905 law ended public subsidies for religious institutions, but instituted no legal or cultural rule against public expression of religious values. So, why are we now told differently?

My only extremely tenuous brush with celebrity is that my Irish teacher (go raibh maith agat, Áine!) happened to tutor on-set the actress who played Luna Lovegood in the Harry Potter films. Among the sort of Dublin people who manage to continually drop into conversation that they went to Trinity, there is a (further) irritating tendency to look down upon the Irish language and use disdain for it as yet another attempt to assert their fragile sense of social superiority.

It is a contemptible and false dichotomy to think that if you appreciate Georgian architecture or Henry Grattan you can’t appreciate the Irish language or Éamon de Valera. Tiresome boors will always try to sell us such dichotomies, but we will not have them.

Paltry though my attempts to learn more Irish have been, what little I’ve picked up has been extremely rewarding and given better insight into the way English in Ireland is spoken and written. (Do the experts still call it “Hiberno-English”, I wonder?) It’s been a pleasure over the past however-long to see Michael Brendan Dougherty – one of America’s most talented journos and a fellow Irish New Yorker – share his own experiences with the Irish language.

MBD’s most recent books column at National Review explores two books concerning Irish, and moves from the Gaeltacht of the mind to a book about Leopolis/Lwów/Lviv/Lemberg in Galicia. City of Lions, incidentally, is published by Pushkin Press, which has proved an almost inexhaustible source of good reads (e.g. Oliver VII).

The recent read I most enjoyed, however, is Gordon Campbell’s delightful combative romp through English translations of the Bible, Making God Speak English. The professor sheds particular light on the thriving culture of pre-Reformation translations of holy writ in the vernacular in general and the English tongue in particular, bursting numerous bubbles of Protestant mythology along the way.

Par example:

Wyclif is a seminal figure in the long road to the catastrophe of the Reformation, with its legacy of decades of wars of religion and centuries of interconfessional animosities that live on in the twenty-first century, but the idea that he was the first translator of the complete Bible into English is a myth. The Middle English Bible, as Henry Ansgar Kelly calls it in his recent reassessment, was in Professor Kelly’s authoritative view neither the work of Wyclif nor of his Lollard followers, but was rather a wholly orthodox Bible with origins in the University of Oxford. It was immensely popular, because it enabled readers and their listeners to understand the readings from the Bible that they heard at Sunday Mass.

I learnt much from Prof. Campbell’s enjoyable submission and you might too.

The Port of London

Officially there are or have been various Londons: first the City of London, founded in AD 43 and a mere square mile to this day, then the County of London created in 1889, and the creature called Greater London has also existed in varying shapes and forms since 1965.

But there is also the Port of London, which has existed since the first century and was once the busiest port in the world, bringing the riches of empire to the metropolis from the four corners of the earth.

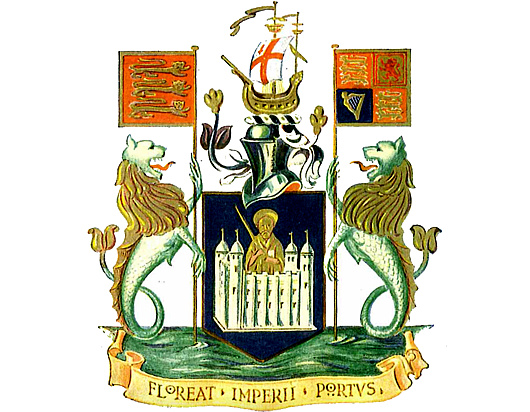

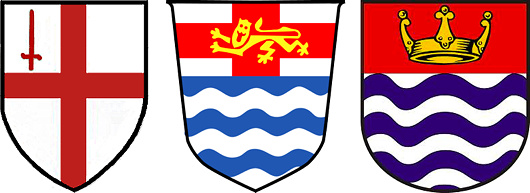

The arms of the City of London, London County Council, and Greater London Council.

All these Londons, of course, have over the centuries been granted or assumed their own coats of arms as heraldic emblems of their importance. The Port of London Authority was created in 1908 by an Act of Parliament which some scholars argue is the first law in the world mandating codetermination or workers’ participation in the board.

Its coat of arms was granted a year later in 1909 and features on its shield Saint Paul, the patron saint of London bearing his usual sword, issuing forth from the Tower of London.

Its coat of arms was granted a year later in 1909 and features on its shield Saint Paul, the patron saint of London bearing his usual sword, issuing forth from the Tower of London.

The crest above the shield is a galley bearing on its mainsail the arms of the City of London — the Lord Mayor is ex officio the Admiral of the Port of London.

Sea lions act as supporters, also bearing standards of the royal arms of England and of the United Kingdom, while the motto proclaims in Latin May the Port of the Empire Flourish.

For proper heraldry nerds, the arms are blasoned:

Shield: Azure, issuing from a castle argent, a demi-man vested, holding in the dexter hand a drawn sword, and in the sinister a scroll Or, the one representing the Tower of London, the other the figure of St Paul, the patron saint of London.

Crest: On a wreath of the colours, an ancient ship Or, the main sail charged with the arms of the City of London.

Supporters: On either side a sea-lion argent, crined, finned and tufted or, issuing from waves of the sea proper, that to the sinister grasping the banner of King Edward II; the to the sinister the banner of King Edward VII.

Befitting the Port of the Empire, the Authority built a grandiose headquarters at 10 Trinity Square, overlooking the Tower of London featured in its coat of arms.

The PLA moved out ages ago and the building is now a hotel, but it often features in films and television as a government (most prominently in the 2012 James Bond film ‘Skyfall’).

The Port of London Authority has its own flag (above) as well as its own ensign — a blue field with a Union Jack in the canton and in the fly a golden sea lion bearing a trident. Distinctive pennants also exist for the Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Authority. (These can be seen here.)

After its foundation the PLA rationalised the layout and organisation of London’s dock system, and their significant constructions allowed the Port to displays its arms on numerous buildings. One such display (above) was recently sold by Westland London.

The main shipping terminal of London is now far down-river at Tilbury and the Authority no longer owns any docks. Its duties however are still numerous — control of Thames ship traffic, navigational safety, pier & jetty maintenance, and conservation — so the century-old Authority still keeps itself quite busy looking after a millennia-old port.

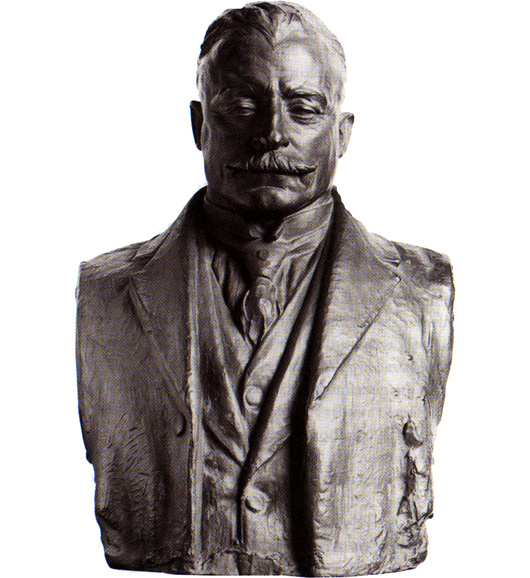

Albert Power & Arthur Griffith

These days the Irish sculptor Albert Power is very rarely spoken of, and I can’t claim to know much about this bronze bust he did of the founder of the original Sinn Féin, Arthur Griffith.

It might be in the National Gallery in Dublin, though I didn’t notice it when I nipped in there with my sister the other day. More likely it is in Leinster House, where there are other busts of prominent figures of 1916-1921 by Albert Power and the better-known Oliver Sheppard.

Unlike Sheppard, Power was a Catholic, which is probably why he was chosen to sculpt the funerary monument of Archbishop Walsh of Dublin who died in 1921. He submitted designs for the new Irish coinage but the Free State wisely chose the far superior set designed by the English sculptor Percy Metcalfe.

As for the subject of this work of art, the Royal Irish Academy’s Dictionary of Irish Biography describes Griffith as “a lucid writer with a vivid turn of phrase”.

The first newspaper he edited was in South Africa where he took the helm of the Middelburg Courant in 1897, attempting to persuade the English-speaking readers with his Boer-friendly views. “I eventually managed to kill the paper,” Griffith wrote, “as the British withdrew their support, and the Dutchmen didn’t bother reading a journal printed in English – the Dutch were quite right.”

Griffith founded Sinn Féin more as a pressure group to support his pet project of reviving the “King, Lords, and Commons” of Ireland, influenced by the Austro-Hungarian Ausgleich of 1867. Independence, he argued, would satisfy the nationalists, while the shared monarchy would keep the unionists happy. In the event, neither half were much enthused by the prospect.

In the aftermath of 1916, Griffith came into his own as a leader and statesman rather than an agitating journalist. His role in the War of Independence and the Treaty negotiations is well known. Without his persuasive arguments in debates, it is highly unlikely the Dáil would have approved the Treaty.

Gloomy civil war soon overshadowed everything, but Griffith died of a cerebral haemorrhage on 12 August 1922 – just ten days before Collins was killed in ambush at Béal na Bláth.

The Steps of the Throne

Who may sit on the steps of the throne in the House of Lords?

Much was made of the Prime Minister’s decision to sit in the House of Lords when they were going through stages of the bill to invoke Article 50 last year. Theresa May had the right to sit on the steps of the throne in the Lords chamber by virtue of being sworn to the Privy Council, as all holders of the four Great Offices of State are (and usually their opposition Shadows as well).

But who else is granted the privilege of lodging their posterior in such a prominent locale?

The Companion to the Standing Orders and Guide to the Proceedings of the House of Lords provides some guidance:

1.59 The following may sit on the steps of the Throne:

· members of the House of Lords in receipt of a writ of summons, including those who have not taken their seat or the oath and those who have leave of absence;

· members of the House of Lords who are disqualified from sitting or voting in the House as Members of the European Parliament or as holders of disqualifying judicial office;

· hereditary peers who were formerly members of the House and who were excluded from the House by the House of Lords Act 1999;

· the eldest child (which includes an adopted child) of a member of the House (or the eldest son where the right was exercised before 27 March 2000);

· peers of Ireland;

· diocesan bishops of the Church of England who do not yet have seats in the House of Lords;

· retired bishops who have had seats in the House of Lords;

· Privy Counsellors;

· Clerk of the Crown in Chancery;

· Black Rod and his Deputy;

· the Dean of Westminster.

Pretoria Philadelphia

Andries Pretorius grew up on his father’s farm near Graaf-Reinet in the Cape of Good Hope, but the Great Trek took him (and many other Boers) into the South African interior. Pretorius’s victory, against all odds, over Dingane’s Zulu forces at Blood River in 1838 was to be commemorated from that day forevermore by Afrikaner piety as Geloftedag — the Day of the Vow. When the South African Republic (ZAR) was established in 1852 the capital was Potchefstroom, but Andries’s son Marthinus founded the city of Pretoria Philadelphia in 1855 to be the new capital of the Transvaal.

The four colonies at the end of the continent were conjoined in 1910 as the Union of South Africa, with Pretoria (as it was soon shortened to) named the seat of the executive and thus the nation’s capital. The parliament met in Cape Town and the highest courts in Bloemfontein so that, in some sense, the new nation had three capitals — administrative, legislative, and judicial. As the seat of the visible sovereignty of the realm, the Governor-General, as well as the Prime Minister’s administration and cabinet, however, it was Pretoria that held precedence.

We’ve already examined Kerkplein — Church Square — at the heart of the city, but the rest of the capital is worth exploring further. (more…)

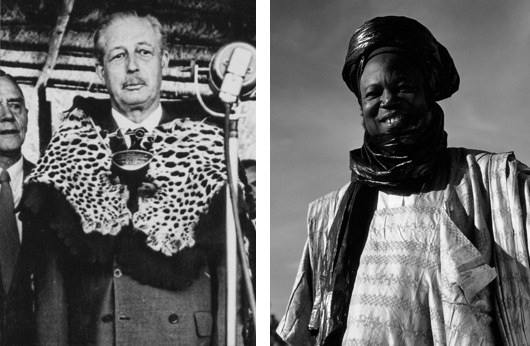

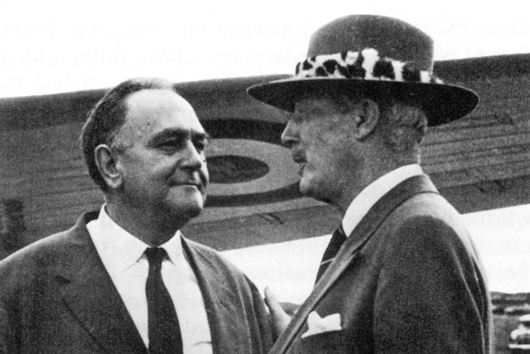

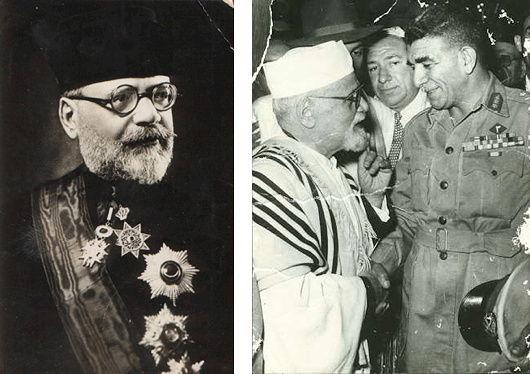

Supermac and the Sarduana

Macmillan’s Attitude to Class and Race in the Late Empire

Left: Harold Macmillan touring Africa in 1960; Right: Sir Ahmadu Bello, the Sarduana of Sokoto.

Staying over with some Kenyan friends in Wiltshire the other day, the old observation came up that, after the war, the officers settled in Kenya while the sergeants went to Rhodesia. While some of the leading lights of UDI had, in fact, been officers — Ian Smith an obvious case — it’s interesting to note that most of them came from humble backgrounds.

“Smithie” was born well-off in Rhodesia but his father had been a butcher’s son who went out to Africa and made good. Clifford Dupont, the first president of the Rhodesian republic, was born in London of poor East End Huguenot stock. His father had done well in the rag trade and got his son to Cambridge; Clifford became an artillery officer before emigrating to Africa.

Rhodesian Prime Minister Roy Welensky’s father was a Russian Jewish horse smuggler who married a ninth-generation Afrikaner. Roy was the couple’s thirteenth son, and left school at 14 to work on the railways and found success through the trade union movement.

Harold Macmillan, meanwhile, was a Guards officer and Old Etonian who had studied at Oxford. His famous ‘Wind of Change’ speech was just part of the British prime minister’s grand tour of Africa. “Supermac” started in Nigeria, where — unlike in some other parts of the continent — much of the native aristocracy had been preserved and coopted throughout colonial rule.

Proving Orwell’s observation that the English are the most class-ridden nation on earth, the PM felt comfortable amongst black African patricians in a way he couldn’t amongst members of the ruling white African elite from humble backgrounds.

In one of the ICBH’s oral history group discussions, Perry Worsthorne relates:

Somebody at some point has to mention, in any discussion of British politics, snobbery and class. I remember travelling and reporting on the ‘Wind of Change’ speech. We went to stay on the last bit, just before going on to Salisbury, was it the Sardauna of Sokoto who was he the premier of the Northern Nigerian region. Macmillan talked to us after he had seen him, he was flying on to Welensky the next day.

Macmillan used to have a sundowner with the correspondents covering his trip, and over whisky and sodas he told us how much more at home he felt with the Sardauna, who reminded him of the Duke of Argyll – ‘a kind of black highland chieftain’ – than he would feel in Salisbury as the guest of a former railwayman, Sir Roy Welensky. Snobbery, pure snobbery.

The British metropole was always ready to make racial distinctions and discriminate accordingly, yet it still tended to look upon outright racism with an air of disdain, as something slightly unsporting (or worse: foreign).

In the imperial periphery, racial attitudes amongst whites often differed greatly from Britain. This was most obviously so in South Africa, which for all intents and purposes embarked upon a radical revolutionary rejection of the British model of governance from 1948 with the implementation of apartheid. Rhodesia, needless to say, was another exception, if arguably more mild. “How different it would all have been,” Worsthorne somewhat patronisingly wondered, “if Ian Smith had been a gentleman.”

Meanwhile Nigeria’s Sir Ahmadu Bello — the Sarduana of Sokoto — was a statesman of cautious action, and his refusal to become Nigerian prime minister upon independence (he preferred sticking to his existing role as the powerful premier of the northern province) sadly deprived the federal state of the wisdom and experience which may have prevented its later descent into disarray. He was murdered by Major Nzeogwu during the 1966 coup d’état.

Differences of race or class aside, it’s telling that both the white low-born railwayman Welensky and the black patrician Bello ended up as knights of the realm.

Lionel Smit

Suid-Afrikaanse portretskilder

Een van die mees geskoolde portretskilders vandag is die Pretoriaanse kunstenaar Lionel Smit (geb. 1982).

’n Skilder en beeldhouer, Mnr Smit woon en werk in Kaapstad en is die wenner van ’n ministeriële toekenning vir bydrae tot visuele kuns van die Wes-Kaapse regering. Sy werk is reeds ingesluit in die visuele kunste eksamen vir die Nasionale Senior Sertifikaat. Nie sleg vir ’n kêrel in sy dertigerjare!

Smit se skilderye herriner my aan die werk van die Engelse skilder Catherine Goodman. Hier is net sommige van sy portrette.

St Paul’s Survives

Crossing the Thames as I walked home from the pub last night, I looked down the river and saw the sturdy dome of St Paul’s standing out, illuminated in the winter night.

As it happens, it was exactly seventy-seven years ago last night — on the 29th of December 1940 — that the iconic photograph often called ‘St Paul’s Survives’ (above) was captured.

Hopeful as that sight must have been, it was a pretty grim time. But four and a half years later (below) the cathedral was illuminated not by the lights of enemy firebombs but by great searchlights forming a massive ‘V’ in the sky: it was 8 May 1945 — Victory in Europe.

Another year gone. We’ve survived.

Warwick Street Church

Over in Soho there is a curious little church with a fascinating history. The parish of Our Lady of the Assumption & St Gregory in Warwick Street started out as the house chapel for the Portuguese embassy in Golden Square, later occupied by the Bavarian embassy.

In recent years the Archdiocese of Westminster has placed the church in the care of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, and they have put new life into the strong musical tradition of the parish.

As chance would have, in my capacity as a professional web designer I was commissioned to design a new website for the parish.

You can view the new Warwick Street website here, and read a little more about its interesting history and architecture.

“Events did not choose the terrorists; powerful white people did.”

Helen Andrews on Zimbabwe

Robert Mugabe leading Ian Smith into the Zimbabwean parliament, 1980.

It is rare to find journalism as informed and insightful as this piece on Zimbabwe by Helen Andrews in National Review. In the aftermath of Mugabe’s clumsy downfall and his succession by a powerful apparatchik and experienced political operator, Helen explores the Rhodesian crisis and attempts to answer the question: could it really have gone any other way?

Any idea that liberal reform on the part of the Rhodesian state could have saved it is a non-starter, because the anti-imperialists were implacable and — I do not know a gentle way to put this — they were quite happy to lie. I do not mean just the professional liars of the Soviet propaganda shop, or the pundits who lazily referred to the Rhodesian system as “apartheid,” or the guerrillas who told Shona villagers that ZANU had successfully dynamited the Kariba Dam, or the foreign journalist who scattered candy around a garbage bin and captioned the resulting photo “Starving children searching for food in Salisbury.” Ralph Bunche had a doctorate from Harvard, a Nobel Peace Prize, and a co-author credit on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and when it came to imperialism, he lied.

“Colonial authorities like the noted Englishman, Lord Lugard, doubt that the African race, whether in Africa or America, can develop capability for self-government.” When I first read that in Bunche’s 1936 pamphlet “A World View of Race,” I felt a lurking suspicion that I had read a sentence of Lord Lugard’s beginning with the very words “The method of their progress toward self-government lies…” I had. His next words are “along the same path as that of Europeans.” Even making allowances for CTRL-F’s not having been invented yet, Bunche’s remark is plain slander. With Harvard Ph.D.s pulling stunts like this, it is hard to summon much indignation at a garden-variety diplomatic lie like the U.N. claim, by which sanctions were justified, that Rhodesia had committed an act of aggression by maintaining its status quo.

She does go a little easy on Smith, who despite his many strengths was just as willing to play fast and easy with the truth. (He was a politician, after all.) But then as we are so used to hearing that Smithie was a little Hitler it’s a welcome restorative.

When I moved to South Africa, I did so at least in part because I wanted to see it before it became “the next Zimbabwe”. Having come back, I was impressed by the relative robustness of many of its institutions, and the certain robustness of many of its people. Rather than a Zimbabwe-style collapse, South Africa seemed destined for a slow, ungainly descent into perpetual malaise.

The recent ascent of Cyril Ramaphosa – who on behalf of the ANC ran rings round the NP negotiators during the transition talks of the early ’90s – gives hope to many. I’m too cautious to be optimistic, but Mr Ramaphosa is clever, intelligent, skilful, and more likelier to keep the unions on side.

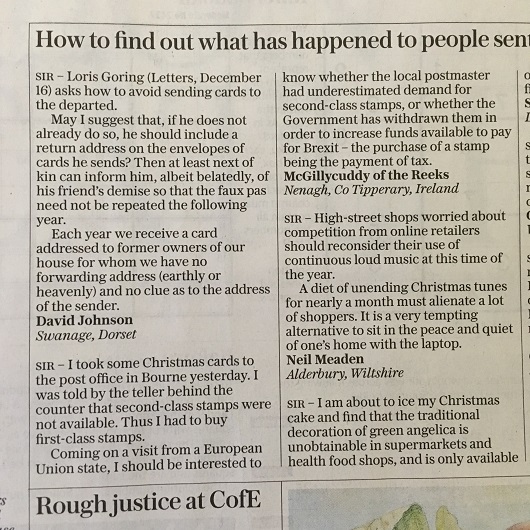

The McGillycuddy of the Reeks

How lovely to see a member of the Gaelic nobility – in this case, the McGillycuddy of the Reeks – having a letter printed in the newspaper (Daily Telegraph, Letters, Wednesday 20 December 2017).

His title is somehow the most fun of all the Chiefs of the Names, though not all bearers of the chiefdom have found it amusing. In the early years of the BBC, the ‘Green Book’ instructing comedy producers what they could and could not get away with contained the instruction ‘Do not mention the McGillycuddy of the Reeks or make jokes about his name’. Clearly a protestation had been made.

Looking at the map of Kerry on my kitchen wall, the eye often drifts to McGillycuddy’s Reeks themselves, the “black stacks” amongst which can be found Corrán Tuathail, Ireland’s tallest mountain.

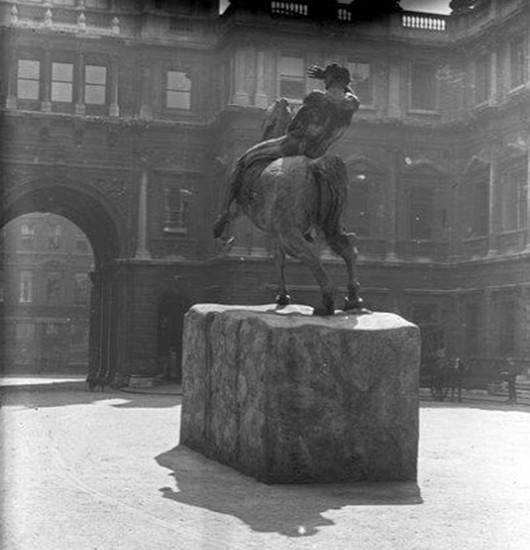

Physical Energy

I came across it by surprise one day, walking through the park. It was almost eerie — all the more so for being unexpected. George Frederic Watts’s sculpture “Physical Energy” was well known to me when I lived in South Africa as it graces the Rhodes Memorial in Cape Town — a rough Greek temple staring out northwards into the vast continent of Africa, as Rhodes himself liked to do.

Unknown to me, another cast of the statue was made and given to the British government, which placed it in Kensington Gardens. It was this copy I stumbled upon while traversing the park to Lily H’s drinks party in the garden of Leinster Square.

It is one of the most aptly named sculptures I can think of, as there is a raw brutish physicality to it, and somehow a sense of tremendous force, power, and energy. Watts was primarily a painter, so that he achieved this great work of sculpture is all the more remarkable. I don’t actually like it: there is something uncomforting and almost vulgar about it, or perhaps just taboo. (Like Rhodes himself.) But it is amazing all the same.

While “Physical Energy” is primarily associated with Cecil Rhodes it was not commissioned in his honour. Watts conceived it in 1886 after having done an equestrian statue for the Duke of Westminster. The first cast wasn’t made until 1902 and was exhibited at the Royal Academy for the first time in 1904 (above).

From there it made its way to Cape Town where it stands today a vital component of the monument to Rhodes. (It even features as the crest on Rhodes University’s coat of arms.) The second cast from 1907 is this one that sits in Kensington Gardens, while a third cast from 1959 now sits beside the National Archives of Zimbabwe in Harare.

This year the Watts Gallery in Surrey commissioned a fourth cast to commemorate the two-hundredth anniversary of the artist’s birth — and that cast now flaunts its bronze in the courtyard of the Royal Academy. It remains on view until the Cusackian birthday in March 2018.

“Get me ze Führer!”

Stereotypes of Nazi generals in British war films

“The reason for my uniform being a slightly different colour to yours

is never explained.”

The British are, of course, obsessed with the Nazis. There are many reasons for this, amongst which we must include the large number of really quite good war films produced during the 1950s and 1960s.

For some indiscernible reason these movies have the virtue of being eternally rewatchable and many a cloudy Saturday afternoon has been occupied by Sink the Bismarck!, Where Eagles Dare, or The Colditz Story.

The genre also deploys with a remarkable regularity a number of familiar tropes of ze Germans which the above clip from a British comedy sketch programme (introduced to me by the indomitable Jack Smith) aptly mocks.

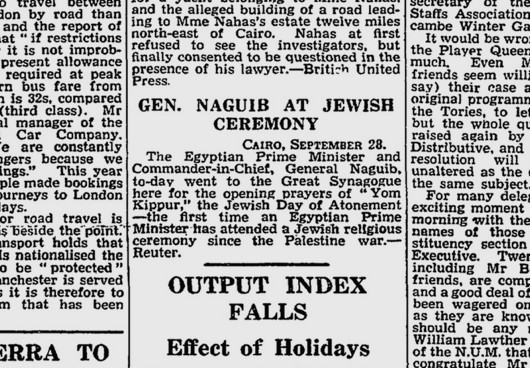

Nahum Effendi and Cairo’s Lost World

Stumbling across the newspaper clipping above was a sad reminder of a lost world. Taken from the front page of the Manchester Guardian of Monday 29 September 1952, it describes the Egyptian leader General Naguib attending a Yom Kippur service just two months after the coup that overthrew the country’s monarchy. None of the Jewish places of worship in Cairo are known as the “Great Synagogue”, so I presume this must have been the Adly Street Synagogue (Sha’ar Hashamayim).

The Chief Rabbi of the Sephardic community in Egypt at the time would have been Senator Rabbi Chaim Nahum Effendi. A creature of the Ottoman world, Rabbi Nahum was born in Smyrna in Anatolia, went to yeshiva in Tiberias on the Sea of Galilee, and finished his secondary education in a French lycée.

After earning a degree in Islamic law in Constantinople, he started his rabbinic studies in Paris while also studying at the Sorbonne’s School of Oriental Languages. Returning to Anatolia he was appointed the Hakham Bashi, or Chief Rabbi, of the Ottoman empire in 1908 and honoured with the title of effendi.

After that empire collapsed, Rabbi Nahum was invited to take up the helm of the Sephardic community in Egypt in 1923. A natural linguist and a gifted scholar, the chief rabbi’s talents were apparent to all, and he was appointed to the Egyptian senate as well as being a founding member of the Royal Academy of the Arabic Language created to standardise Egyptian Arabic.

Rabbi Nahum (front row, third from left) at the foundation of Egypt’s Arabic academy.

The foundation of the State of Israel was a godsend for many Jews but spelled the beginning of the end for Egypt’s community. Zionists were a distinct minority among Egyptian Jews — many of whom were part of Egypt’s (primarily anti-British) nationalist movement — but Israel’s defeat of the Arab League in the 1948 War embarrassed Egypt’s ruling classes and stoked anti-semitism amongst the populace. Violent attacks against Jewish businesses were tolerated by the authorities and went uninvestigated by the police. Unfounded allegations of both Zionism and treason were rife, and discriminatory employment laws were introduced.

The 1952 Revolution did not improve things, as the tolerant but decaying monarchy was replaced by a vigorous but nationalist and pan-Arabist military government. Faced with such continuing depredations, the overwhelming majority of Jewish Egyptians fled — to Israel, Europe, and the United States. Rabbi Nahum eventually died in 1960, by then something of a broken man I imagine.

Cairo was once a thriving cosmopolitan city of Muslims, Christians, and Jews — and many communities of outside origin. The Greeks, who first arrived twenty-seven centuries ago and in 1940 still numbered tens of thousands, have all left. The futurist Marinetti was the most famous of the Italian Egyptians, whose numbers in the 1930s were numerous enough to warrant several branches of the Fascist party. Since the 1952 Revolution they are all gone too. Some Armenians remain, but not many. As for Jews, there are six left in Egypt.

Sic transit gloria mundi.

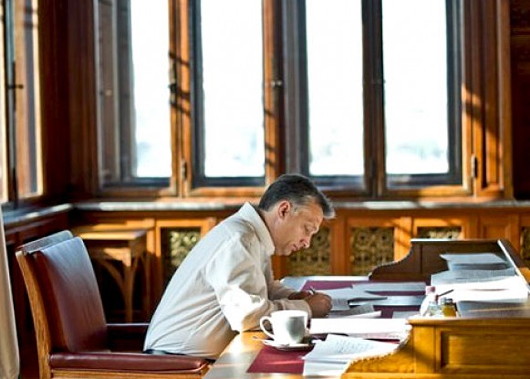

‘The right thing to do is to act virtuously, rather than just talk about doing so’

Welcome to Budapest. Today I do not wish to talk about the persecution of Christians in Europe. The persecution of Christians in Europe operates with sophisticated and refined methods of an intellectual nature. It is undoubtedly unfair, it is discriminatory, sometimes it is even painful; but although it has negative impacts, it is tolerable. It cannot be compared to the brutal physical persecution which our Christian brothers and sisters have to endure in Africa and the Middle East. Today I’d like to say a few words about this form of persecution of Christians. We have gathered here from all over the world in order to find responses to a crisis that for too long has been concealed. We have come from different countries, yet there’s something that links us – the leaders of Christian communities and Christian politicians. We call this the responsibility of the watchman. In the Book of Ezekiel we read that if a watchman sees the enemy approaching and does not sound the alarm, the Lord will hold that watchman accountable for the deaths of those killed as a result of his inaction.

Dear Guests,

A great many times over the course of our history we Hungarians have had to fight to remain Christian and Hungarian. For centuries we fought on our homeland’s southern borders, defending the whole of Christian Europe, while in the twentieth century we were the victims of the communist dictatorship’s persecution of Christians. Here, in this room, there are some people older than me who have experienced first-hand what it means to live as a devout Christian under a despotic regime. For us, therefore, it is today a cruel, absurd joke of fate for us to be once again living our lives as members of a community under siege. For wherever we may live around the world – whether we’re Roman Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox Christians or Copts – we are members of a common body, and of a single, diverse and large community. Our mission is to preserve and protect this community. This responsibility requires us, first of all, to liberate public discourse about the current state of affairs from the shackles of political correctness and human rights incantations which conflate everything with everything else. We are duty-bound to use straightforward language in describing the events that are taking place around us, and to identify the dangers that threaten us. The truth always begins with the statement of facts. Today it is a fact that Christianity is the world’s most persecuted religion. It is a fact that 215 million Christians in 108 countries around the world are suffering some form of persecution. It is a fact that four out of every five people oppressed due to their religion are Christians. It is a fact that in Iraq in 2015 a Christian was killed every five minutes because of their religious belief. It is a fact that we see little coverage of these events in the international press, and it is also a fact that one needs a magnifying glass to find political statements condemning the persecution of Christians. But the world’s attention needs to be drawn to the crimes that have been committed against Christians in recent years. The world should understand that in fact today’s persecutions of Christians foreshadow global processes. The world should understand that the forced expulsion of Christian communities and the tragedies of families and children living in some parts of the Middle East and Africa have a wider significance: in fact they threaten our European values. The world should understand that what is at stake today is nothing less than the future of the European way of life, and of our identity.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We must call the threats we’re facing by their proper names. The greatest danger we face today is the indifferent, apathetic silence of a Europe which denies its Christian roots. However unbelievable it may seem today, the fate of Christians in the Middle East should bring home to Europe that what is happening over there may also happen to us. Europe, however, is forcefully pursuing an immigration policy which results in letting extremists, dangerous extremists, into the territory of the European Union. A group of Europe’s intellectual and political leaders wishes to create a mixed society in Europe which, within just a few generations, will utterly transform the cultural and ethnic composition of our continent – and consequently its Christian identity.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We Hungarians are a Central European people; there aren’t many of us, and we do not have a great many relatives. Our influence, territory, population and army are similarly not significant. We know our place in the ranking of the world’s nations. We are a medium-sized European state, and there are countries much bigger than us which should, as a matter of course, bear a great deal more responsibility than we do. Now, however, we Hungarians are taking a proactive role. There are good reasons for this. I can see – and I know through having met them personally – how many well-intentioned truly Christian politicians there are in Europe. They are not strong enough, however: they work in coalition governments; they are at the mercy of media industries with attitudes very different from theirs; and they have insufficient political strength to act according to their convictions. While Hungary is only a medium-sized European state, it is in a different situation. This is a stable country: the political formation now in office won two-thirds majorities in two consecutive elections; the country has an economic support base which is not enormous, but is stable; and the public’s general attitude is robust. This means that we are in a position to speak up for persecuted Christians. In other words, in such a stable situation, there could be no excuse for Hungarians not taking action and not honouring the obligation rooted in their Christian faith. This is how fate and God have compelled Hungary to take the initiative, regardless of its size. We are proud that for more than a thousand years we have belonged to the great family of Christian peoples. This, too, imposes an obligation on us.

Dear Guests,

For us, Europe is a Christian continent, and this is how we want to keep it. Even though we may not be able to keep all of it Christian, at least we can do so for the segment that God has entrusted to the Hungarian people. Taking this as our starting-point, we have decided to do all we can to help our Christian brothers and sisters outside Europe who are forced to live under persecution. What is interesting about this decision is not the fact that we are seeking to help, but the way we are seeking to help. The solution we settled on has been to take the help we are providing directly to the churches of persecuted Christians. We are not using the channels established earlier, which seek to assist the persecuted as best they can within the framework of international aid. Our view is that the best way to help is to channel resources directly to the churches of persecuted communities. In our view this is how to produce the best results, this is how resources can be used to the full, and this is how there can be a guarantee that such resources are indeed channelled to those who need them. And as we are Christians, we help Christian churches and channel these resources to them. I could also say that we are doing the very opposite of what is customary in Europe today: we declare that trouble should not be brought here, but assistance must be taken to where it is needed.

Dear Friends,

Our approach is that the right thing to do is to act virtuously, rather than just talk about doing so. In this way we avoid doing good things simply in order to burnish our reputation: we avoid doing good things out of calculation, as good deeds must come from the heart, and for the glory of God. Yet now it is my duty to talk about the facts of good deeds. My justification, the reason I am telling you all this, is to prove to us all that politics in Europe is not necessarily helpless in the face of the persecution of Christians. The reason I am talking about some good deeds is that they may serve as an example for others, and may induce others to also perform good deeds. So please consider everything that I say now in this light. In 2016 we set up the Deputy State Secretariat for the Aid of Persecuted Christians, which – in cooperation with churches, non-governmental organisations, the UN, The Hague and the European Parliament – liaises with and provides help for persecuted Christian communities. We listen to local Christian leaders and to what they believe is most important, and then do what we have to. From them I have learnt that the most important thing we can do is provide assistance for them to return home to resettle in their native lands. We Hungarians want Syrian, Iraqi and Nigerian Christians to be able to return as soon as possible to the lands where their ancestors lived for hundreds of years. This is what we call Hungarian solidarity – or, using the words you see behind me: “Hungary helps”. This is why we decided to help rebuild their homes and churches; and thanks to Hungarian Interchurch Aid, in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon we also build community centres. We have launched a special scholarship programme for young people raised in Christian families suffering persecution, and I am pleased to welcome some of those young people here today. I am sure that after their studies in Hungary, when they return to their communities, they will be active, core members of those communities. And we are also working in cooperation with the Pázmány Péter Catholic University on the establishment of a Hungarian-founded university. The Hungarian government has provided aid of 580 million forints for the rebuilding of damaged homes in the Iraqi town of Tesqopa, as a result to which we hope that hundreds of Iraqi Christian families who now live as internal refugees may be able to return to their homes. We likewise support the activities of the Syriac Catholic Church and the Syriac Orthodox Church. I should also mention something which perhaps does not sound particularly special to a foreigner, but, believe me, here in Hungary is unprecedented, and I can’t even remember the last time something like it happened: all parties in the Hungarian National Assembly united to support adoption of a resolution which condemns the persecution of Christians, supports the Government in providing help, condemns the activities of the organisation called Islamic State, and calls upon the International Criminal Court to launch proceedings in response to the persecution, oppression and murder of Christians.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

When we support the return of persecuted Christians to their homelands, the Hungarian people is fulfilling a mission. In addition to what the Esteemed Bishop has outlined, our Fundamental Law constitutionally declares that we Hungarians recognise the role of Christianity in preserving nationhood. And if we recognise this for ourselves, then we also recognise it for other nations; in other words, we want Christian communities returning to Syria, Iraq and Nigeria to become forces for the preservation of their own countries, just as for us Hungarians Christianity is a force for preservation. From here I also urge Europe’s politicians to cast aside politically correct modes of speech and cast aside human rights-induced caution. And I ask them and urge them to do everything within their power for persecuted Christians.

Soli Deo gloria!

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories