About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Roots and Permanent Interests

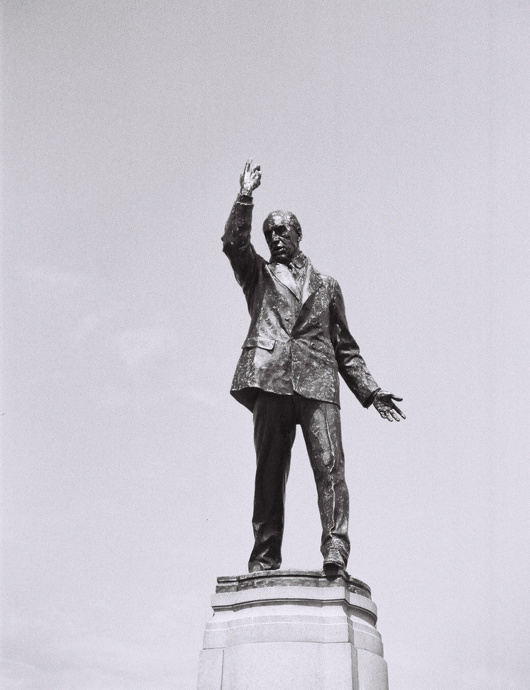

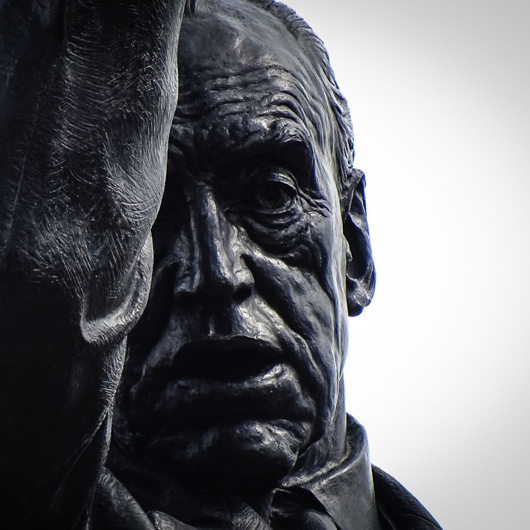

Carson at Stormont

Few statues in Ireland are as dramatic as that of Edward Carson at Stormont. The unionist leader is depicted in amidst an oratorical flourish, doubtless in one of his speeches to mass meetings condemning home rule.

In the 1910s as the rebirth of an Irish parliament looked more likely, Carson took up the cause of fighting home rule on behalf of Ireland’s large Protestant minority who feared Catholic domination. When the anti-home rulers realised the cause was losing, they retreated from Irish unionism to Ulster unionism. If home rule was to be granted, Ulster must be exempted. In the end this meant home rule was granted to a parliament covering two-thirds of the Irish province of Ulster — six counties that would henceforth be known as Northern Ireland.

“His larger than life-size statue,” one historian wrote, “erected in his own lifetime in front of the Northern Ireland parliament at Stormont, symbolizes the widely held perception that Northern Ireland is Carson’s creation.”

This is of course the great irony, given that Edward Carson was a Dublin boy through and through. While instrumental in ensuring northeastern Ireland’s exemption from an Irish parliament, Carson actually had little to do with the entity thereby created. When offered the premiership of Northern Ireland he declined it on the grounds of having no real connection with the place.

Craig, not Carson, is the true father of Northern Ireland; he imbued the new statelet with a sense of bigotry and tribal hatred that Carson lacked. The Dubliner urged Ulster’s new leaders to treat the province’s Catholics well.

“We used to say that we could not trust an Irish parliament in Dublin to do justice to the Protestant minority,” Carson said. “Let us take care that that reproach can no longer be made against your parliament, and from the outset let them see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from a Protestant majority.”

Alas, it became apparent to Carson that discrimination and inequality were becoming in-built within Northern Ireland’s government, from the Parliament at Stormont down to the lowest forms of local government. He confided to a Catholic friend in London that rather than being an integral part of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland was turning into “a second-class dominion”.

After partition Carson was created a British judge and accordingly ennobled. (Disappointingly the plaque on his Dublin birthplace next to Conradh na Gaeilge refers to him by the incorrect style of ‘Lord Edward Carson’.) He settled at Clever Court near Minster-in-Thanet, Kent, and never lived in his native Ireland again.

Nonetheless he was held in awe and reverence by the Protestant Unionists of Ulster, who commissioned the striking statue by Leonard Stanford Merrifield that stands in front of Parliament Buildings, Stormont — now home to the Northern Ireland Assembly. It was unveiled by Craig, by then ennobled as Lord Craigavon, while Carson was alive and present in July 1932, joined by a crowd of 40,000 well-wishers.

Carson died in 1935 and was given the rare honour of a state funeral. HMS Broke brought his Union-Jack-draped coffin back to Ireland — albeit to Belfast — and he was interred in the Anglican Cathedral of St Anne. Northern Ireland claimed him even in his final burial: soil from each of its six counties was scattered on his coffin when laid to rest in the tomb.

Still his statue stands at Stormont, gesturing stridently as if to challenge an entire province — a province he by his own description had little to do with. Calls for it to be removed emanate occasionally from typically boring quarters and have so far been rebuffed — wisely. Carson, unlike many of those who cherished his memory, was an honourable man, and it is a pity it took so long for the Protestants of Ulster to heed the advice of their confrère from Dublin.

St Nicholas, Our Patron

As by now you are all well aware, today is the feast of Saint Nicholas, the patron-saint of New York. His patronship (patroonship?) over the Big Apple and the Empire State date to our Dutch forefathers of old – real founding fathers like Minuit, van Rensselaer, and Stuyvesant, not those troublesome Bostonians and Virginians who started all that revolution business.

Despite being Protestants of the most wicked and foul variety, the New Amsterdammers and Hudson Valley Dutch maintained their pious devotion to the Wonder-working Bishop of Myra and kept his feast with great solemnity.

After New Netherland came into the hands of the British (and was re-named after our last Catholic king) the holiday continued to be celebrated by the Dutch part of the population, and was greatly popularised in the early nineteenth century by the publication of a curious volume entitled A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty which purported to be by one Diedrich Knickerbocker.

In fact it was by Washington Irving, the first American writer to make a living off his pen, who did much to popularise St Nicholas Day in New York as well as to revive the celebration of Christmas across the young United States.

While, aside from hearing Mass and curling up with a clay pipe and a volume of Irving (being obsessive, I have two complete sets) here are a few links that shed some light on New York’s heavenly protector.

Historical Digression: Santa Claus was Made by Washington Irving

New-York Historical Society Quarterly: Knickerbocker Santa Claus

The History Reader: The 18th Century Politics of Santa Claus in America

The New York Times: How Christmas Became Merry

The Hyphen: Thomas Nast’s Illustrations of Santa Claus

– plus: Santa Claus and the Ladies

National Geographic: From Saint Nicholas to Santa Claus

Previously: Saint Nicholas (Index)

Dolosse

dolos, pl. dolosse

Visitors to the seaside and frequenters of port cities will be familiar with those oddly shaped concrete forms which are dropped together to form breakwaters and prevent erosion.

It turns out that they have a name of Afrikaans origin: dolos (plural dolosse).

‘Dolos’ is believed to be a contraction of ‘dollen os’, the name for the children’s toy of knucklebones or jacks. This particular shape was invented by Aubrey Kruger and Eric Mowbray Merrifield to rebuild the revetments of East London’s artificial harbours following the great storm of 1963.

Kruger fashioned a smaller version of the shape to show his idea to Merrifield, and legend has it that Kruger’s father visited them on the quayside and asked Wat speel julle met die dolos? (‘What are you playing at with the jack?’) The name stuck.

In 2016 the South African Mint released a two-rand ‘crown’ coin depicting the dolos as a tribute to this example of South African ingenuity.

Stellenbosch

would be as beautiful as Oxford or Cambridge

until I saw it.”

— AIDAN HARTLEY

Soho Iridescent

Stiff & Trevillion’s 40 Beak Street in London

Beak Street in London is teeming with turquoise iridescence since the completion of a new office building by the architectural firm of Stiff & Trevillion earlier this year. A joint project between property investment companies Landcap and Enstar, Number 40 Beak Street has been purchased for £40 million by Damien Hirst — the canny businessman who sells dead animals in formaldehyde glass boxes. The over-27,000-square-foot building will serve as the primary London studio for Hirst and headquarters for his company, Science (UK) Ltd, in addition to housing a restaurant at ground level.

Five storeys tall, 40 Beak Street features a number of roof terraces in addition to cornice work designed by Hertfordshire-based artist Lee Simmons. The glazed bricks — “hand dipped” the architects tell us — make for a welcome change from the omnipresence of metal and glass on one end of the spectrum and cheap monotone brick on the other.

The PR hype makes much of bringing a bit of artistic and creative edge back into Soho, a neighbourhood whose final glory days have been depicted in a much-praised book by the Telegraph’s Christopher Howse. We’re not so sure.

Hype aside, 40 Beak Street is an excellent addition to the London landscape and the designers are to be commended for their fine eye for detail. Someone at Stiff & Trevillion knows what they’re doing.

Sunday in Stellenbosch

In recent rambles I came upon an old article from the Spectator in which the late and much-praised Richard West reported from Stellenbosch — “this old and incomparably beautiful town in a valley of vineyards” — on the Sunday after the Dutch Reformed Church renounced apartheid in 1986.

“The students here seem to be confident, cheerful, enthusiastic and full of fun,” West wrote. “Half of them seem to be in love, holding hands and gazing adoringly into each other’s eyes.”

As I walked over the university lawn, I turned at the hoot of a horn, and saw that it came from a motor-bike cop, who wanted to get the attention of and wave to a friend. Small children were paddling in the brook that runs by an avenue of old oaks. Bigger children, spotlessly dressed, went smiling off to their Sunday school, while their elders went to the mother church, where there has been a congregation since 1684. The present building, begun in 1715 and renovated during the 19th century, now has a peculiar boomerang shape so that if you are sitting near one of the ends, you cannot see or hear what is going on at the other side. The church cannot compete in appearance with some of the houses of Stellenbosch, which justify Ruskin’s remark that ‘the only contribution to domestic architecture for centuries was made by the Dutch at the Cape’.

The congregation who filled the church was impeccably dressed, the men all wearing coats and ties, though most women were hatless with summer dresses of normal length at the arms and legs, instead of the 17th-century garb one tends to associate with Calvinism. The congregation has little to do except sing the metrical psalms. The prayers are said by the minister, who devotes much if not most of the hour-long service to giving his sermon. …

Stellenbosch University, which was where apartheid began, is now working to dismantle the system. Whereas the English universities are stuck in the stale polemics of 20 years ago, the Afrikaners are bubbling with radical new ideas. Whereas foreigners once read Afrikaans papers ‘to learn what they were thinking’, it is now essential to read them to find any thinking at all. The two best English newspapers are edited by Afrikaners. The Afrikaners still believe in the future. …

Mr West died in 2015 but it would be fascinating to see what he would make of the Eikestad these days.

Around

“By contrast, Hungary’s 100,000 Jews—a larger presence relative to the country’s population of 8 million—walk unmolested to synagogue in traditional Jewish costume and hold street fairs with minimal security presence.” The Real Modern Anti-Semitism

No American writer has wielded such influence, John Rossi writes. So why is he so little known today? The Strange Death of H.L. Mencken

Damon Searl on Uwe Johnson: The Hardest Book I’ve Ever Translated.

Then there are the mythical and miraculous islands of the medieval Atlantic

120 years after the Spanish-American War, here are five books to help you better understand American imperialism.

The always-worth-reading Michael Brendan Dougherty explores what the Catholic traditionalists of the 1960s and 1970s were thinking. (More people, however, are talking about his look at Francis’s record as pope.)

In Manhattan, John Massengale suggests there are better ways to get around town.

Argentina’s most beloved bibliophile Alberto Manguel on the great books that are now lost to history.

In Hungary, like everywhere else, people are marrying later, with demographic consequences. Or is this changing? The country is not just experiencing a fertility spike, Lyman Stone reports. Hungary is winding back the clock on much of the fertility and family-structure transition that demographers have long considered inevitable. Is Hungary Experiencing a Policy-Induced Baby Boom?

Speaking of which, from the same author, what about Poland’s Baby Bump?

Meanwhile in New England, an entitled Harvard academic pulls rank on the mother and child living in an affordable unit in their apartment building in a telling tale of class and hierarchy in America.

Holborn Town Hall

The Metropolitan Borough of Holborn was the smallest borough of London both in geography and population so perhaps it’s not surprising that its town hall was a pretty but rather humble affair. The civic pride and municipal pomposity for which this realm was once renowned are nowhere on show in this handsome building which, but for a few details, could easily be mistaken for a hotel, office building, or private residences.

Holborn Town Hall was built in stages, with the public library on the left-hand side completed in 1894 by the Holborn District Board of Works to a design by Isaacs. With the erection of the borough in 1900, a town hall was needed, and the central and right-hand sections of the building were added between 1906 and 1908 by the architects Hall & Warwick.

In 1965 the borough was merged with St Pancras to form the new London Borough of Camden. It was decided to consolidate the civic government at St Pancras Town Hall, to which the local government union members objected. To placate their ire, a bar for the use of employees was erected atop the annexe being added to the Camden (ex St Pancras) Town Hall — quickly nicknamed ‘the White Elephant bar’.

Though long sold off and converted into office space, the arms of the old borough of Holborn still grace the first floor balcony.

Knickerbocker Spires

Before the age of the skyscrapers, New York’s church spires dominated the horizon and dwarfed their neighbours just like in the medieval towns and cities of the old world — as this photo from the 1900s shows.

Here St Patrick’s Cathedral holds court, with the St. Nicholas Collegiate Reformed Protestant Dutch Church poking up a few blocks down Fifth Avenue.

Slightly north on that same boulevard sits the grand renaissance palazzo of the University Club, with the spire of the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church poking up behind it.

Ten Books

Marian Chashuble

Now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, it was embroidered by the Sisters of Bethany, a Protestant order of nuns based in Clerkenwell. The Sisters specialised in church vestments and embroidery, and this object is believed to have been produced between 1909 and 1912.

Fr Anthony Symondson SJ has written in greater depth about Comper and the Sisters of Bethany here.

Inside Governors Island

This intriguing little island in New York Harbour has always held something of a fascination for me — viz. articles previous on the subject. Aside from its interesting history there is the matter of the complete lack of foresight in ending its military use as well as the failure to imagine a future use suitable to its history and, if the word is not hyperbole, majesty.

Gothamist recently featured a new peek inside some of the abandoned buildings on Governors Island, a mere selection of which are reproduced here. (more…)

Hollandic Fever

Adapted from the Deborah Moggach novel of the same name, ‘Tulip Fever’ is a curious concoction. Some of the plot holes are so big you could drive a coach and horses through them. For example, how is it that – in Calvinist-controlled seventeenth-century Amsterdam – there is a massive Catholic convent perfectly accepted by everyone and operating as if nothing is out of place? It’s the size of Norwich Cathedral! (In fact, it is Norwich Cathedral – this entire production was filmed in Great Britain.)

The often excellent Chrisoph Waltz is curiously mismatched with his role here: a little bit too much of a parody of the proud, pious Amsterdam merchant in the start, which makes his eventual transformation a little unconvincing. The plot also shows little of the brilliance of its co-writer Sir Tom Stoppard. (In fact, there’s a bit too much plot.) At least Dame Judi Dench is effortless in her role as the unnamed Abbess of St Ursula. Tom Hollander is thrown in for a laugh, in a role suited to his abilities.

For curiosity’s sake the most interesting casting choice was Joanna Scanlan, known as the useless press officer at DOSAC in ‘The Thick of It’. Here she is the dressmaker Mrs Overvalt, but she was Vermeer’s cook Tanneke in ‘Girl with the Pearl Earring’. If my rudimentary calculations are correct, this means she has been in two-thirds of twenty-first-century films set in the Dutch seventeenth century.

It is, however, a beautifully shot production, for which I suspect we have the cinematographer Eigil Bryld to thank. (He’s worked on one seventeenth-century film before, and on another set in the Low Countries.) Bookended by scenes of Friedrichian romanticism (I’m into that) the film encourages me in my deeply felt belief that we need to revive seventeenth-century Dutch domestic architecture as a style.

Scribbled Notes

Does anyone talk on the phone anymore? Reading a book in which a casual conversation takes place and the main character hangs up the phone, the fact that the author reveals this hanging-up seems surprising. We didn’t need to know it took place over the phone. But it situates the exchange in a concrete reality of sorts.

I never really feel comfortable speaking on such devices, so I only ever speak to people who are far away, pretty much only my parents. Other people use them voluminously, but I only know for certain myself of very few who do. When CSG was alive (and suspicions still linger over the nature of his death), CDL would sometimes spend hours talking to him on the phone, like two old ladies who suffer too many ailments to get out and meet in person. (I’ll concede that they were in different countries.)

I find the very idea revolting. What could one possibly discuss for hours at length down a strange device it’s not even comfortable to handle? My thoughts don’t flow properly over the phone in a way they do naturally face-to-face or via the written word.

I remember Farley’s stories about when he was a correspondent in Rome and — taking no heed of time differences — his editor would phone him up and deliver long screeds which Farley would make a few accommodating noises to then gently place the phone down on his bedside table and let the man carrying on while he gently faded back into the realms of slumber.

Then again the Major sometimes phones during his lunchtime saunter and he usually has information worth sharing or complaints that are satisfying to share, imbued with doom-laden pessimism.

On the whole, then, I am not a telephone enthusiast. Their primary purpose now is of course as smart phones — incredibly useful devices which have lured us into slavery and the impossibility of living without them.

The book I am reading — the one I mentioned earlier — is The Informers by Juan Gabriel Vásquez. I had never read any Colombians — except for Nicolás Gómez Dávila, but as he spoke in aphorisms he is in another category entirely. Colombia is a mysterious realm to me, with only little snippets having ever filtered down to me. When I was a boy, for a year or two we had the daughter of a Colombian senator at our school who taught me the words to ‘La Cucaracha’ but who, out of fear, was always entirely silent on the subject of home; she point blank refused to talk about it. (There were many killings in those days, and I suppose she was abroad for her own safety.)

But the Colombians are by no means an un-literary people — far from it. As someone briefly educated in Argentina it’s sometimes difficult to concede there is any culture in the Americas outside of Argentina, but Colombia’s Gabriel García Márquez is well-known outside his home country. I suppose I will have to read him some day but I decided to start with Vásquez having read a review of one of his more recent books in the Speccie.

Much as one hates to admit that any living writer is worth reading, Vásquez is good, and just a few pages in I got in touch with my old school friend Lucas to tell him I thought he’d like it. Lucas is an Austro-Argentine-Peruvian-Estadounidense living in Guatemala so he gets it, though what he gets is hard to describe. This novel, for example, is not action-driven but primarily from the interior life, which I think is what I mean.

Ever since school days, Lucas has always had a particular genius for over-analysis that I have always criticised him for and do my best not to provoke or indulge in, though this is difficult. Tell him you love the rain. “What? Do you? Wow! But what is it about the rain you love? Is it a primeval force? Is it because we [meaning humanity] are farmers? Well I suppose you’re Irish so you have to love the rain.” (Lucas has always wanted to be Irish.) Thus, having a furiously intensive interior life himself, Lucas might enjoy a novel set primarily (though not entirely) in the interior realm.

Hippo was here the other day in between Rome and Scotland or wherever. (He’s off to Montepulciano for a few weeks, actually.) We had a jolly auld lunch at the Farmers’ Club and discovered over a cigarette and gin-and-tonic aperitif a mutual love for Balzac. Balzac got it — well, not quite, but pretty damned close enough. I am forever reading Balzac, and going on about him to Beatrice who is mostly uninterested (her late father called him “Balls-ache”) though she is perhaps the person with whom I discuss writing most often.

And so, finishing Vásques, I am continuing through Balzac, and others. I am off to the New World later this week, for not terribly long, but I am bringing Gerard Skinner’s book on Father Ignatius Spencer, Barry Hutton’s history of Lisbon, Sandy’s Corduroy Mansions (seeing as I used to live in Pimlico), Lindie Koorts’s biography of DF Malan, and one or two others in the hope of making some progress and being entertained, informed, or enlightened.

We shall see.

Mugabe and Friends

The recent election (such as it was) in Zimbabwe brought to mind the Nando’s television advert of Robert Mugabe and his old mates.

Gaddafi, Mao, Saddam, and Idi Amin all make an appearance, and even (somewhat incongruously) die ou krokodil, P.W. Botha.

Classical New England

A reminder that Russell Kirk once described the piano nobile of the Old State House in Hartford, Connecticut, as:

“perhaps the most finely proportioned rooms in all America”

Given the elegant restraint and classical detail of the old Senate chamber, it’s hard to disagree.

Observations

All those interested in the history of the workers’ struggle would have enjoyed a letter to the editor printed in last week’s Observer.

Floreat Etona, left and right

Alex Renton is correct when he points out that the 20 old Etonian MPs currently sitting are all Tories, but this is far from usually the case (“Our educational apartheid laid bare”, Books, New Review). The first OE to be elected a Labour MP was in 1923, and the party consistently had OE representation on its benches from then all the way to 2010. Even Clement Attlee’s transformative postwar Labour government included two old Etonians: Hugh Dalton as chancellor of the exchequer and Frederick Pethick-Lawrence as India secretary.

Andrew Cusack (Conservative, non-OE)

London SE1

Of course, no one actually reads the Observer, so it went entirely unnoticed.

I have acquired a dangerously successful rate of my pedantic missives being printed in periodicals. The editors of the Irish Times, Times Literary Supplement, Catholic Herald, and even the Tablet have all been guilty of lapses in judgement in this regard.

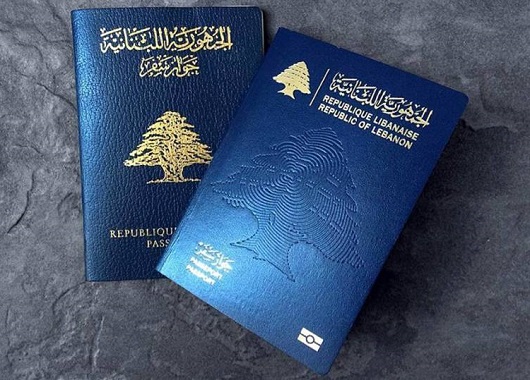

Passport Innovation

It is a truth universally acknowledged that changes to passport designs are almost never improvements. Take the new Lebanese passport above. The old passport was a simple and elegant affair, with the noble cedar gracing centre stage, beautiful Arabic script above and the French text in a sturdy typeface below.

The new one, however, is a sorry thing altogether. The central motif is an odd pseudo-fingerprint impression of a cedar, and the national emblem is repeated on a smaller scale above left in gold. Next to that the name of the state is written in Arabic and French. But then it is mistranslated into English as ‘Republic of Lebanon’ – the actual name of the state is the ‘Lebanese Republic’.

(I could bore you with a tirade against the continuing encroachment of the English language into Lebanon – par example street signs used to always be in French and Arabic but often you see newer ones in Arabic and English – but that is a subject for another day.)

It is not at all that passports cannot be done well to a modern design – just look at Swiss passport designs from 1985 onwards, and we’ve already mentioned the elegant new Norwegian numbers. But Lebanon’s new passport gives the impression of being done by a third-rate in-house designer at a midranking corporation. As a country with enormous soft-power potential Lebanon could do with guarding and guiding its brand better and passports are just one aspect of many involved in a country’s image.

Passports, of course, have to change their design every so often to keep one step ahead of counterfeiters and fraudsters. In the past ten years most countries have substantially changed their passports to give them a biometric capability, though in most cases this led to little difference on the cover beyond a change in thickness and the addition of the biometric emblem.

Redesigns of the interior pages are more common and the results have been poor: my U.S. passport now features garish patriotic eagles and such, while luckily I have a few years left before I have to submit to the new Irish passport with its infelicitous pseudo-celtic tourist backgrounds. Foolishly I still haven’t got my UK passport but I understand that’s had its inner pages tarted up recently as well.

The upcoming change for British passports, of course, is that following the UK’s exit from the European Union the passports are going back to blue. Of course, they never actually needed to change to EU burgundy, but civil servants and ministers rather typically chose to change it regardless.

If recent experience shows anything, however, it’s that we should be looking to Scandinavia for models of how to do modern design well.

Rosary on the Coast

By all accounts last Sunday’s Rosary on the Coast was a resounding success. The initiative started out in Poland, where last year thousands of Catholics gathered at the nation’s borders and coastline to pray for the salvation of Poland and the world. Then a month later Ireland joined in with a Rosary on the Coast for Life and Faith, encircling the country in prayer.

Last Sunday, Great Britain got in on the action, and for three countries which have suffered centuries of Protestant domination it seems we have done rather well on these shores. Thousands of people from every variety of ethnicity, class, background, and experience gathered to pray the Rosary “for the spiritual wellbeing of our nations” (as the organisers put it).

The Rosary on the Coast was organised by lay people but supported by the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster as well as many other bishops and of course priests, many of whom accompanied and led in prayer the lay-organised groups around Britain. The rectors of the three national Marian shrines at Walsingham in England, Carfin in Scotland, and Cardigan in Wales all gave their backing and encouragement to the initiative.

Experience has taught me not to be surprised by the success of such ventures. I remember when the Cardinal renewed the consecration of England & Wales to the Immaculate Heart of Mary (with the visit of the Fatima visionaries’ relics). I didn’t have plans to go but friends were driving in from the West Country for it so I thought I’d meet up with them beforehand and go along.

We tried to get in but the doors of the cathedral were shut and a crowd waiting outside – it turned out the church was packed to the gills with the faithful. A pint later we tried again and they had just reopened the doors and let us in. Every bit of the mother church of the diocese was crammed with people, from Filipino maids to peers of the realm. Pews, aisles, side chapels – there was barely room to move. Priests were hearing confessions and the service was ongoing. We’re so used to being an embattled minority that sometimes we forget that we’re still the biggest show in town.

The good people at the Catholic Herald have collected a variety of photos from around the country, of which just a small sample are presented here. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories