About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

The greatest church architect you’ve never heard of

The greatest church architect

you’ve never heard of

Ludwig Becker and His Churches

For such a prolific church architect of such high quality, not much is known about Ludwig Becker and, alas, he seems to be little studied. Born the son of the master craftsman and inspector of Cologne Cathedral, Becker had church building in his blood. He studied at the Technische Hochschule in Aachen from 1873 and trained as a stone mason as well.

In 1884 Becker moved to Mainz where he became a church architect and in 1909 he was appointed the head of works at Mainz Cathedral, a position he held until his death in 1940. His son Hugo followed him into the profession of church architecture.

That’s about all I can find out about Becker. But here are a selection of some of his churches, to get a sense of his agility in a wide variety of styles.

St Joseph, Speyer, is my favourite of Becker’s churches for the beautiful organic fluidity of its style. Here Art Nouveau, Gothic, and Baroque are mixed somehow without affectation. Rather enjoyably, it was built as a riposte to a nearby monumental Protestant church commemorating the Protestant Revolt. These two rival churches are the largest in the city after its famous cathedral. (more…)

Rashtrapati Bhavan

Debates rage in the trad community as to whether, in the context of India, it is more sound to support the Congress Party or to take some relief in the policies of Mr Modi and his Indian People’s Party (curiously always known in English as the BJP).

Presented with the choice of left-leaning instability with Congress or Hindutva-oriented instability with the BJP, one recalls Hofrat Kissinger’s comment about the Iran-Iraq War: “Isn’t it a shame they can’t both lose?”

But the recent visit to India of my fellow New Yorker, His Excellency the President of the United States, necessitated his calling in to one of the grandest residences of any head of state the world over: Rashtrapati Bhavan, the residence of the President of India.

Originally called Viceroy’s House, it was designed by Lutyens as the palace of one of the most powerful men on the face of the planet: the Viceroy of India.

But the building of this magnificent structure was an imperial swansong. Opened in 1931, just sixteen years later the subcontinent was partitioned, the Indian Empire and its Viceroy abolished. The Union of India took its place, with a Governor General instead of a Viceroy.

In 1950, this too was abolished as the Union became a republic, and the office of governor general was given a republican whitewash and renamed as President of India.

This head of state is not elected by the voters of the world’s largest democracy except indirectly through a combined college of the national parliament and the state legislative assemblies. Like a governor general, he does have some power but the real force lies in the prime minister — today Mr Modi.

Nevertheless, this building reflects the glory, power, and influence of one of the greatest nations of the earth.

‘Disgraceful Scenes at Stellenbosch’

The 1957 Intervarsity Match

Flicking through the argiewe the other day I stumbled upon this little report from Johannesburg’s Sunday Express of 26 May 1957 describing the displays of disrepute at the annual Intervarsity match, when the University of Cape Town takes on Stellenbosch.

AT STELLENBOSCH

annual rugger booze up

At Stellenbosch many students made the intervarsity match the occasion for a grand drinking spree. A number of them became drunk and disorderly; and here are some of the results of their liquor intake:

- A Cape Town student was hit on the head with a bottle, and was taken to hospital to have a gaping wound stitched.

- Another student was escorted from the pavilion by the police.

- A constable was hit by a bottle, thrown by a student.

- Flying bottles narrowly missed a number of other policemen.

- Although no damage was done, cardboard darts were thrown in the direction of the Prime Minister, to the accompaniment of insulting jeers.

- The pennant on a Cabinet Minister’s car was stolen.

- The chauffeur of the Governor-General’s car hid his pennant (which cost £7.10.0) in case it too disappeared.

- One Cape Town student was found lying drunk among the coloured spectators.

According to a police official, many drunk students armed with bottles of liquor, turned up for the match. So bad was it that he eventually told the gate keepers not to allow them in. A policeman was obliged to stand guard over Ministerial cars.

I’m pleased to say the Sunday Express revealed that “the worst offenders were the Cape Town students”, not the Maties. “Bottles of whisky, vodka, wine and champagne were much in evidence on [the UCT] stands.”

depicting die ridder van Matieland having easily defeated the Ikey dragon.

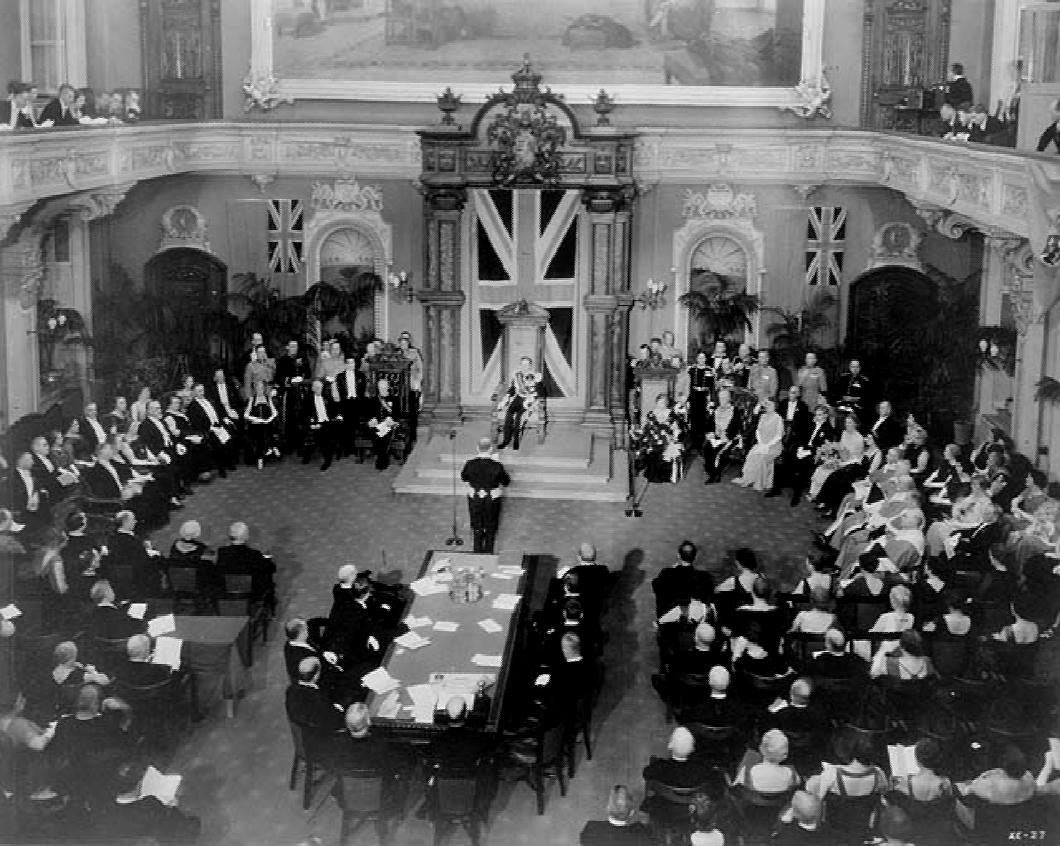

Buchan in Quebec

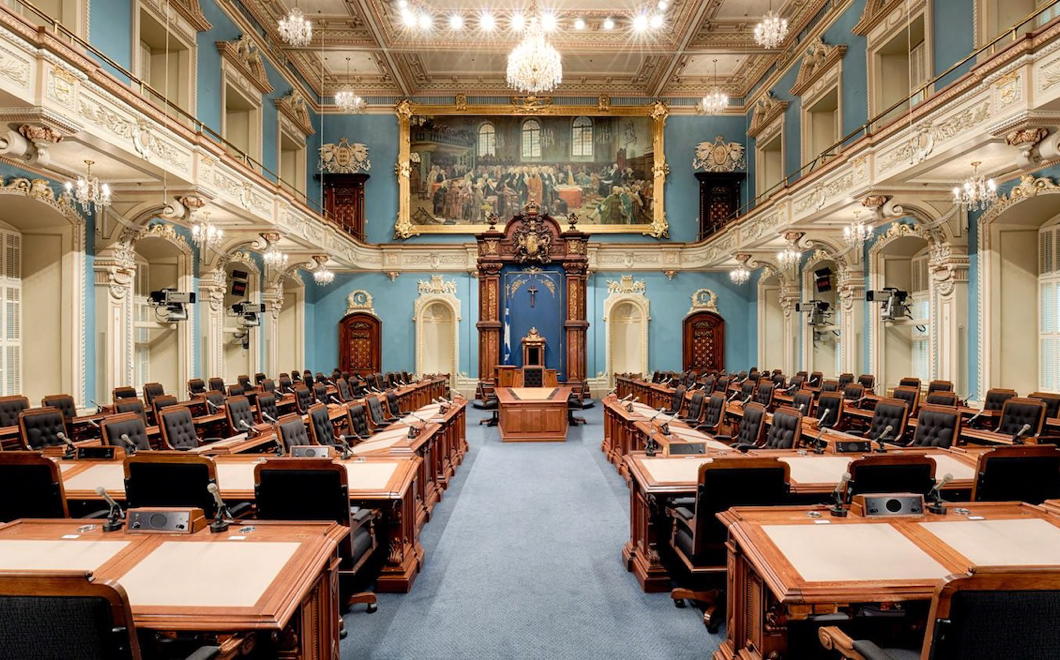

While the Salon bleu in Quebec’s parliament used to be green, the Salon rouge has kept its lordly colour. Conservative Quebec was the last of the Canadian provinces to abolish its unelected upper house which faced the chop in 1968, that year so beloved of duty-shirkers and ne’er-do-wells.

Thirty-three years earlier, the Salon rouge was the scene of a more regal ceremony: the official installation of the Scots writer and statesman John Buchan as Governor General of Canada. Being a Presbyterian with an in-built (but in his case only occasional) tendency to dourness, Buchan wanted to go as an ordinary commoner but the King of Canada insisted on a peerage for his viceregal representative in the dominion.

Thus it was Lord Tweedsmuir who arrived in Quebec in 1935 and was installed as Governor General in the Salon rouge on All Souls’ Day of that year. Above, the Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King gives an address after the swearing-in.

Buchan proved an influential Governor General and helped set the tone of Canada’s monarchy in the aftermath of the 1931 Statue of Westminster that recognised the distinct nature of the Commonwealth realms. He also orchestrated the King’s successful 1939 trip across Canada — which also featured the King and Queen holding court in the Salon rouge of Quebec’s Parliament.

By the time of his death in post in 1940, John Buchan had become His Excellency The Right Honourable The Lord Tweedsmuir GCMG GCVO CH PC. Not a bad end to a good innings.

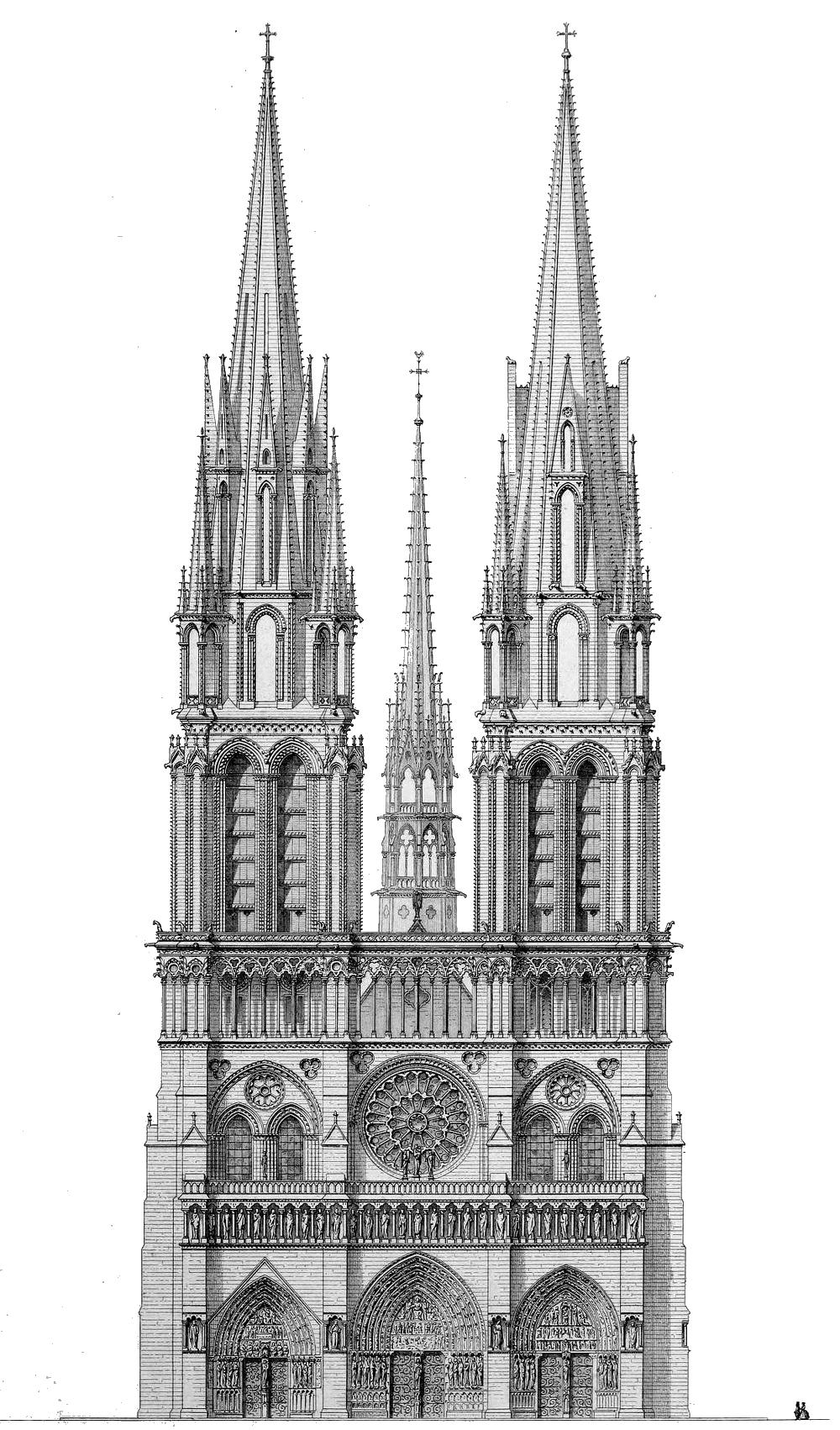

Notre-Dame de Paris

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

1844

Portsmouth Pachyderm

Leach (centre) on being made cadet captain at the Royal Australian Naval College in 1944

A delightful episode is relayed in the Daily Telegraph’s obituary of the late Vice-Admiral David Leach of the Royal Australian Navy.

Leach was the last RAN Chief of Naval Staff to have served in the Second World War but the incident in question dates from the 1950s when he was at the gunnery school in Whale Island in Portsmouth Harbour here in England:

In 1955 he was the course officer for a class of sub-lieutenants who decided to have some fun on their last morning parade, on April 1, by bringing a circus elephant on to the island. The duty officer, warned of the elephant’s approach by the bridge sentry, thought that his leg was being pulled and gave the order to let the pachyderm proceed.

Subsequently the class marched on to the parade ground with the elephant in their midst, surmounted by a mahout dressed as a sub-lieutenant. The beast, being well-trained, picked up the band’s marching step nicely, but Captain “Bunjey” Rutherford, the saluting officer in command of Whale Island, was not amused.

Leach had not been party to the April Fool’s joke, but later that morning, when he took the class results to the captain, he had placed Sub-Lieutenant L E Fant at the top. Rutherford was still not amused, demanding “Fant? Fant? Who’s this feller, Fant?” When the news reached the Admiralty, the Second Sea Lord took a personal interest and called Rutherford to announce, somewhat unkindly: “This is a trunk call.”

R.I.P.

Doom in Bloom

Such paintings were widespread in Catholic England where they served as a vital reminder to the faithful worshipping below of not just the torments of Hell but also the joys of Heaven. In the aftermath of the Protestant revolt, however, such vivid imagery was frowned upon, and the Salisbury Doom was painted over with limewash in 1593. Christ in Majesty was replaced by the royal arms of the usurper queen, Elizabeth I.

It was then forgotten about til its rediscovery in 1819 when hints of colour were discovered behind the royal arms. The limewash was removed, the remnants of the painting were revealed, recorded by a local artist, and then covered over yet again in white. Finally in 1881 the Doom was revealed to the world and subject to a Victorian attempt at restoration with mixed results.

Work on the church’s ceiling in the 1990s allowed experts to better examine the Doom which determined that, while there was a bit of fading, dirt was hanging loosely to the painting and it would be ripe for restoration. It has only been more recently, however, that money has been raised to restore the Doom.

There are other glories in this church yet to be restored, about which more information can be found on the parish’s website.

The Salisbury Doom before restoration (above) and after (below).

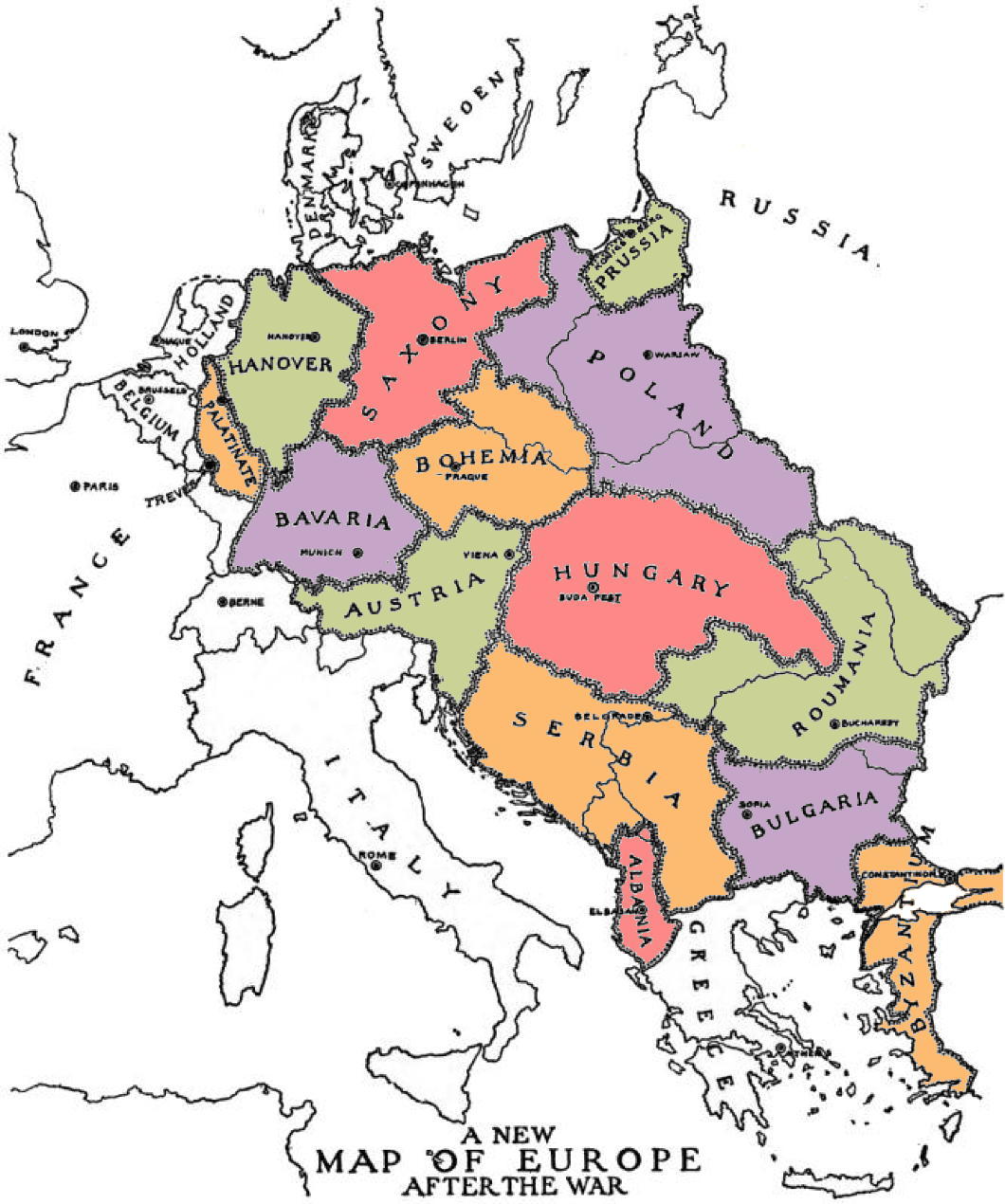

‘Solving’ Middle Europe

Ralph Adams Cram’s First-World-War Plan for Redrawing Borders

Ralph Adams Cram was not just one of the most influential American architects of the first half of the twentieth century: he was a rounded intellectual who expressed his thinking in fiction, essays, and books in addition to the buildings he designed.

Cram (and arguably even more his business partner Goodhue) had a gift for bringing the medieval to life in a way that was neither archaic nor anachronistic but instead conveyed the gothic (and other styles) as living, organic traditions into which it was perfectly legitimate for moderns to dwell, dabble, and imbibe.

His literary efforts include strange works of fiction admired by Lovecraft and political writings inviting America to become a monarchy. These have value, but it’s entirely justifiable that Cram is best known for his architectural contributions.

All the same, amidst the clamours of the First World War this architect of buildings played the architect of peoples and sketched out his idea of what Europe after the war — presuming the defeat of the Central Powers — would look like.

In A Plan for the Settlement of Middle Europe: Partition Without Annexation, Cram set out his model for the territorial redivision of central and eastern Europe “to anticipate an ending consonant with righteousness, and to consider what must be done… forever to prevent this sort of thing happening again”.

Cram, who provided a map as a general guide, predicted the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France, Schleswig-Holstein to Denmark, the Trentino and Trieste to Italy, much of Transylvania to Romania, Posen to a restored Poland, and Silesia divided in three.

Fundamental to the architect’s thinking was that “neither Germany, Austria-Hungary, nor Turkey can be permitted to exist as integral or even potential empires”. Austria and Hungary would be split and Germany needed to be partitioned (not, as some later plans had it, annexed). (more…)

Articles of Note: 5.II.2020

• Some enthusiasts like to go bird-watching, but James Panero of The New Criterion likes to go house-watching. “[O]ur country is fertile ground for good house-watching. Fine examples, of just about any style of any period, abound. What stories they tell if only we listened to their calls.”

• Psephologists are still extrapolating ideas and conclusions from the results of December’s general election here in the UK that handed Boris Johnson a handy majority. One of the most important analyses comes from the philosopher John Gray in the New Statesman: Why the Left Keeps Losing.

• For years, EU leaders have insisted that Brexit would be a disaster for Britain, leaving your country hopelessly isolated, Alexander von Schoenburg, the editor of Europe’s highest-selling newspaper, reports from Berlin. “According to the relentless propaganda of the pro-EU cause, Europe would forge ahead on the global stage, ever more united, while the UK would slide into insularity and decline. But that narrative is starting to look like a delusion.”

• British liberals have created a Europe of their imagination, Ed West writes at UnHerd. But how closely does it resemble reality?

• As the founder of the Anglo-Gaullist Working Group I often ask myself “What would de Gaulle do?” James Pinkerton (the American Conservative) argues that when it comes to Afghanistan, the great Frenchman would advise President Trump to stand his Deep State antagonists down and bring the troops home.

• For centuries Spain faced a perfect storm of enemies that fostered an anti-historical legacy of lies collectively known as the Black Legend. In the University Bookman, Alberto M. Fernandez reviews the surprise Spanish best-seller written by a woman who, according to one newspaper, “has liberated thousands of ideological hostages from a national cancer”.

A Corner in Camberwell

4a-6 Grove Lane by MATT Architecture

Alongside some of its neighbouring streets in Camberwell, Grove Lane has some of the best preserved rows of Georgian houses in south London, interspersed with a few buildings of a more recent vintage. The latest addition to this street is no ostentatious interloper but a contextual classic showing admirable humility and good manners.

Designed by Leicester Square-based MATT Architecture, it’s easy to see why the Georgian Group deemed 4a-6 Grove Lane worthy of a Giles Worsley Award for a New Building in a Georgian Context in 2015.

“The long, thin, wedge–shaped site had lain derelict for decades before being purchased by the current owner,” the architects note.

“The elevation is deliberately split into three to echo the plot width of neighbouring terraces and relies heavily on high quality detailing to lift it beyond pastiche.”

Articles of Note: 11.XII.2019

• The 1930s Oxford social anthropologist J.D. Unwin studied five thousand years of human existence and discovered you can either have a high level of cultural achievement or widespread sexual freedom but never both. Kirk Durston explores why sexual morality may be far more important than you ever thought.

• America’s secular liberalism isn’t secular at all: it is merely the latest stage in the adaptation of an inevitably deracinated Protestantism, Patrick Deneen argues.

• René Rémond’s model of France’s three right wings — Legitimist, Bonapartist, and Orleanist — is breaking down because, Luke Nicastro argues, Emmanuel Macron is co-opting both Orleanists and Gaullists into his electoral family.

• And finally, a historic note, it’s been more than a quarter-century since the late Anthony Lejeune went on A Tour of New York’s Clubland.

The Manor House

For devoted fanatics of Netherlandic architecture — I’m sure you’d count yourself as one as much as I do — a curious example of Dutch revival architecture can be found at No. 316 Green Lanes in the Borough of Hackney. Alighting from Manor House tube station the other day I was surprised to find myself confronted by a fine building which, it turns out, used to be the pub that gave its name to the Underground station.

The first ‘public house and tea-gardens’ of that name was built in the 1830s, and in 1843 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert stopped there for a change of horses. This tavern soldiered on until the arrival of the Piccadilly line which necessitated street widening and the demolition of the pub in 1930.

It was rebuilt in a very handsome brick Netherlandic revival in 1931 and continued on as a pub supplied by the London brewers Watneys.

A purist would object that the style of windows on the gables suggests a vulgar pakhuis (warehouse) on the Amstel while the stepped gable itself is more informed by domestic architecture. But is the privilege of architectural revivals to mix and match, so I don’t think we should complain.

Evidence suggests the pub shut in 2004 and the building was converted to its current retail use.

Alas, I can find no record of the architect, and the building remains un-listed, but I’m glad Hackney is home to this happy Hollandic interloper.

Articles of Note: 22.XI.2019

• In Spiked, James Heartfield urges us to spurn Labour’s counsel and instead stop apologising for the past.

• Michael Brendan Dougherty in National Review wonders if Republican Missouri senator Josh Hawley might be the next Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

• Why would an Eton- and Oxford-educated man assert he ‘supports’ Aston Villa, a football team based in a slum in Birmingham, a city with which he has no connection? Theodore Dalrymple ponders David Cameron’s Big Lie at Law & Liberty.

• At the American Conservative, Rod Dreher ponders the radicalism of today’s left and whether its religious fervour to deny scientific realities like biological sex is driving Trump-hating lefties to back the Donald for president.

• And, for a decent long read, politics professor Daniel E. Burns examines how critics and defenders of liberalism often argue past one another:

It refers, on the one hand, to a set of political practices, and on the other hand, to a political theory that purports to explain those practices. Defenders of liberalism are thinking first and foremost about liberal political practice, which they (almost all) defend by drawing selectively on liberal theory. Critics of liberalism are thinking first and foremost about liberal political theory, which they (almost all) attack by pointing selectively to liberal practice.

In National Affairs, it’s a question of Liberal Practice v. Liberal Theory.

British Columbia in London

Colonial Agents & Provincial Agents-General in the Imperial Capital

JUST WHERE THE elegant Edwardian urbanity of Waterloo Place turns into Regent Street there is an edifice that announces itself as home to the “Agent General for British Columbia”. Built in 1914-1915, it was designed by a not particularly prominent architect named Alfred Burr who did a lot of work for the Metropolitan Police and is also responsible for designing the charming little curator’s lodgings next to Dr Johnson’s House (which he restored 1911-1912).

The listing that protects British Columbia House, at 1-3 Regent Street, describes its style as “rich Baroque with both Roman and Genoese palazzo features composed on a large scale”.

The main entrance is on Regent Street with the province’s delightfully sunny coat of arms carved above the portal, guarded by allegorical figures of Justice and the like above. On the corner with Charles II Street, the inscription on the foundation stone proclaims its laying at the hands of Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught on the sixteenth day of July in 1914.

But who or what on earth was the Agent General for British Columbia? (more…)

The politics of parliamentary colour

When Quebec’s « Salon bleu » was the « Salon vert »

One Westminster tradition replicated in many times and places across the Commonwealth is a convention of colour: the lower house of a parliament is decorated in green, while the upper chamber is decorated in red. This reflects the green benches of the House of Commons and the red ones of the House of Lords.

Officially the plenary chamber of Quebec’s unicameral parliament is boringly the salle de l’Assemblée nationale but because of the colour of its walls it is more often known as the Salon bleu. One’s never surprised when Quebec bucks a trend or (more specifically) rejects an Anglo convention but it turns out the province’s plenary chamber did in fact used to be green until relatively recently.

When the members of the Legislative Assembly (as it then was) first convened in the Hôtel du Parlement in 1886 the walls were actually white. By the opening of the 1895 session the desks had been reappointed in green, but Le Soleil still made reference to the room as the “chambre blanche”. It was only in 1901 that the room was painted a “soft green” and the carpets and other furnishings changed accordingly. It even made an appearance in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1953 film “I Confess”.

From then the chamber was a Salon vert until 1978, when the decision was taken to begin broadcasting the proceedings of the Assemblée nationale.

The television specialists complained that the dark green of the chamber was not visually conducive to the TV cameras available at the time and, looking at the evidence from the 1977 test session (above), one can see their point. Walls of either beige or blue were the options recommended in an official report, and unsurprisingly the national colour was chosen.

The historian Gaston Deschênes has mentioned the technical requirements of broadcasting also coincided with a desire to break with a “British” tradition. Certainly the government of the day, René Lévesque’s Parti Québécois, didn’t mind the change, while Maurice Bellemare — “the old lion of Quebec politics” and sometime leader of the old Union nationale — was deeply pleased that the chamber adopted the colour of Quebec’s flag.

So the walls were repainted sky blue and the furnishings changed accordingly, resulting in the Salon bleu we know today (below).

A tweet from the Assemblée’s official account shows two photos looking towards the chamber’s entrance from before (above) and after (below) it was made ready for television.

All the same, green is not universal amongst Commonwealth lower (or only) chambers. It’s not even universal in Canada: Manitoba joins Quebec in its azure tones while British Columbia’s is red-dominated.

Quebec was the last of Canada’s provinces to abolish its upper house, the Legislative Council, in 1968 (at the same time the lower house was renamed the National Assembly). The Legislative Council’s former meeting place is, of course, red, and the Salon rouge is used for important occasions like inductions into the Ordre national du Québec or the lying-in-state of the late Jacques Parizeau.

The Palais de Tokyo

In the early 1930s the City of Paris decided the Musée de Luxembourg had become too small to continue as the city’s gallery of contemporary art. At the same time, the French Republic was beginning to think it needed a proper museum of modern art to display its own collections as well. The City and the Republic joined forces to build a new palace of art in time for the 1937 International Exposition.

While the City and the Republic would house their collections at a single site the museums were to remain separate, so in May 1937 the Palace of the Museums (plural) of Modern Art was inaugurated by President Lebrun.

Because of its riparian location on the Avenue de Tokio (renamed to Avenue de New-York in 1945) the building quickly became known as the Palais de Tokyo. (more…)

Angela Wrapson

In Rome the other week I was sorry to hear from a mutual friend that Angela Wrapson had died. She had been fighting cancer for a while, but she was quite a fighter and was one of those people you thought would always go on.

Angela was, amongst many things, a fixture of that strange yet familiar galaxy known as the Scottish arts world. She was, for example, director of the Stanza poetry festival for some years.

She was a keen listener, a good conversationalist, and a very welcoming hostess in the wing of Brunstane House that she and her husband George bought back in the 1970s.

From 2015 to 2017, George was the MP for East Lothian and I am still ashamed in those two years I never managed to reciprocate Angela and George’s hospitality by having them round.

Nonetheless, I was pleased to see she got the plaudits she deserved with obituaries in the Scotsman, the Times, and the Herald.

May she rest in peace.

Turn the Ship Around

The UK’s Supreme Court is a nine-year experiment that has failed

If you open the hood of your car and mess about with the engine you can hardly be surprised if, later, it stops working at just the wrong moment. Likewise, constitutions by their very nature ought not to be fiddled with, and the current crisis in Westminster is ample proof.

Under the old system – before the Supreme Court and Fixed Term Parliaments Act – there would have been no crisis at all. The Prime Minister would see there is no working majority in favour of any way forward and would simply call a general election. Hypothetically, this would result in a government with a majority capable of moving business forward – all without much controversy.

Since FTPA was passed, however, the PM now needs a two-thirds majority in Parliament in order to bring about an election and the Opposition has up to this point blocked any chance at referring to the electorate in fear that the voters will back Boris over Corbyn. At the time it was passed, proponents argued not much would change with FTPA, as the point of the Opposition is to try and become the Government and what Opposition in its right mind would ever turn down the chance to fight a general election at a moment of crisis?

Enter now the Supreme Court in a timely intervention over the Prime Minister’s decision to end the longest parliamentary session on record by advising the Queen to prorogue Parliament over the long-planned conference recess. The Court has only been in operation since 2009, when it was created because legal experts and constitutional gurus told us it wasn’t correct for the highest court of appeal to technically be part of the legislature (even though this practice had been ratified by centuries of experience and had failed to present any difficulties).

The old system was robust and flexible; it is the innovation which has created stasis. Before it bent: now it breaks. Britain’s unwritten constitution is often summarised as “The Crown-in-Parliament is Supreme”. That means the Government exercises power with the authority of the Sovereign under the scrutiny of and with the confidence of Parliament. With the final court of appeal removed from the Parliament, where did that leave the Supreme Court? The justices have sought to answer with a judgement asserting that they are the ultimate authority in the land, supreme even over the exercise of the Royal Prerogative.

This runs contrary to the entire thrust of the UK’s constitutional development, which – up until this point – has been to strengthen scrutiny of the exercise of power and to increase the accountability of those who exercise that power. The Supreme Court’s judgement is a massive expansion of the justices’ own power without any counterbalancing accountability. When the Prime Minister exercises power he is held accountable by his need to maintain the confidence of his party colleagues and of the House of Commons. If he fails to do so he can be replaced as PM or ultimately his party can be chucked out by voters in a general election. How are Supreme Court justices to be held accountable though? What actions can voters take when justices overstep the bounds?

If justices seek to exercise political power than they must face concomitant levels of scrutiny and accountability that don’t – yet – exist. They cannot expect to receive the traditional obeisance and deference of politicians and the general public that the pre-Supreme Court judiciary received if they fail to observe the same self-restraint and respect for the Parliament’s role as legislature that the pre-Supreme Court judiciary observed.

The fundamental question is what the appropriate reaction of an ordered society is when judges overstep their bounds. If a Conservative majority government – presuming that is even the result of the next election – fails to respond appropriately to the Supreme Court’s ruling it is difficult to see how the UK can avoid going down the American route of a highly politicised judiciary. Ultimately, this would mean greater parliamentary oversight in the appointment of justices to the Supreme Court. Would they be prepared for long hearings in parliamentary committee rooms where every aspect of their past (including their student antics at university) were dredged before the public? Would voters be prepared to accept that an unaccountable Supreme Court can overturn any action of a democratically accountable executive or law passed by a democratically elected parliament with which the justices disagreed?

A Conservative majority government could easily, by simple Act of Parliament, remove the Royal Prerogative from the purview of the Supreme Court and further clarify (meaning restrict) the Court’s room for manoeuvre. But perhaps this isn’t a problem that can be fixed by tweaking. Trying to make sure justices understand they don’t have the authority to make naked power grabs seems impossible when you have an establishment that, in legal circles and otherwise, believes its will overrides the democratic mandate of the people in a constitutional monarchy. Restrictive legislation can help clarify, but it won’t strike at the heart of the institutional cockiness the Supreme Court exudes. (Remember that it ominously chose the Greek letter omega – symbolising finality – as its official emblem.)

Far better, then, to concede our own humility and accept that the Supreme Court has been a nine-year experiment which has failed. This would mean repealing those provisions of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 which created Supreme Court in 2009 and going back to having Lords of Appeal in Ordinary sitting as the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords. There would be no problem with Law Lords continuing to sit in Middlesex Guildhall across Parliament Square as the Supreme Court does today.

Opponents must accept that the unaccountability the Supreme Court seeks to exercise belongs to another era: we live in the age of transparency, accountability, and taking back control.

History is littered with coups and grabs for power. Some succeed, others are attempted and fail. This “constitutional coup” can be foiled, but it requires a general election, a Conservative majority, and a government intent upon deliberate action.

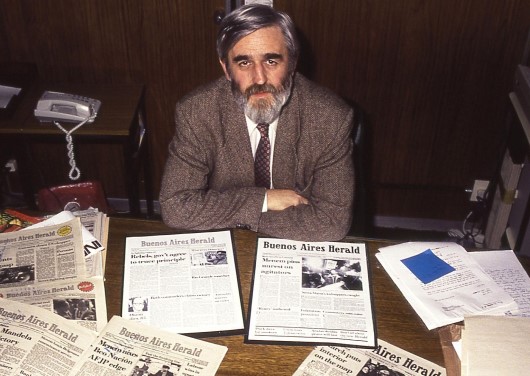

Andrew Graham-Yooll

A giant of Argentine journalism died this summer: Andrew Graham-Yooll.

Born in Buenos Aires early in 1944 to a Scottish father and an English mother, Graham-Yooll made his name at the premier institution of Anglo-Argentina, the now-defunct daily Buenos Aires Herald which he joined aged 22 in 1966.

“The Herald newsdesk supped for Dutch courage a local brandy,” the Times notes, “supplemented with a pâté that Graham-Yooll made of goose livers lashed with gin. A chain-smoker, he would construct tiny houses from matchsticks.”

As the Herald’s news editor during Isabel Perón’s presidency he published the names of dissidents who had gone missing or “disappeared” and, more bravely, continued to do so after Señora Perón was succeeded by a military junta.

The new rulers, who Borges warmly welcomed as “gentlemen”, put Graham-Yooll on trial for publishing interviews with the guerrillas who were terrorising the country. He was acquitted, but accepted the gentle advice of the judge who suggested he might find existence more comfortable outside the borders of the Argentine Republic.

Graham-Yooll continued writing for the Daily Telegraph and Guardian in Great Britain but made a brief foray home in 1982 during the Falklands War before being permanently welcomed home by a democratic government in 1984. Ten years later he was appointed editor of the Herald.

“Things you think you can rely on and trust are just not there,” Graham-Yooll said in Edinburgh when picking up his OBE in 2002.

“You can’t trust the bank, you can’t trust the post office or the people who sell you a house. You can’t trust the politicians, obviously. It’s a friendly society but it lacks strict rules. It’s evil, but it is also attractive to live in a place where you don’t have to live by rules.”

“I don’t know where I could go now. It was always home, even in the worst days, and it still is.”

Four Reasons Rodden and Rossi are Wrong on Northern Ireland

Economics alone will not join what history has rent asunder

Academics John Rodden and John Rossi have an interesting but poorly argued piece in the normally-quite-good American Conservative “asking” the question of whether Brexit could unite Ireland at last. While ostensibly they merely posit the question, they lay out an unintended-consequences scenario for Irish political unity coming about.

If Brexit goes “wrong” then the imposition of a hard border in Ireland will drive Northern Ireland’s Protestant/Unionist community into the arms of the Republic. If there’s no hard border, then Northern Ireland and the Republic will progress down a path of natural economic integration while, Rodden and Rossi argue, “economic divergence from Britain with no hard border will show northerners that their long-term interests now lie with Dublin”.

There are some obvious problems with the Rodden/Rossi scenario.

First, the EU’s customs and economic union has already applied to Northern Ireland and the Republic for decades now and yet Northern Ireland is not economically integrated into the Republic. Of goods that leave Northern Ireland, the rest of the UK is still the strongest destination: In 2016 £10.5 billion of goods left NI for Great Britain, compared to £2.7 billion to the Republic.

True, Ulster is more vulnerable in that a bigger chunk of their exports head south of the border than the Republic’s exports head north of it. But after decades of trade barriers being torn down by the EU these two economies remain very much distinct.

Second, Rodden and Rossi fall into the trap of economic determinist thinking. The roots of Republic of Ireland/Northern Ireland divide are not economic. Ireland’s six north-easterly counties were excluded from the Irish Free State in 1921 because of the tribal fears of those counties’ Protestant/Unionist majorities of being powerless in a state that would have an overwhelming Catholic/Nationalist majority. Some of these fears were well-reasoned and considered, others were wildly irrational and bigoted.

The important thing to realise is that the divide between Nationalists and Unionists is not formed on the basis of economic arguments, though either side can deploy economic arguments in their favour. It is simply not the case that a significant chunk of Northern Ireland’s Protestant Unionist community are going to wake up some day soon and think “Well, I’ve always liked our Union Jacks, Orange marches, and devotion to the Queen but Northern Ireland might be able to achieve a 2.3% better rate of growth if we join the Republic so I’ll run up the tricolour and paint my curbside green, white, and orange”.

Third, as Rodden and Rossi confusingly point out, the coming demographic majority Catholics will achieve in Northern Ireland does not automatically equate to all-Ireland unity: An astonishingly large proportion of Northern Irish Catholics wish to maintain links to the United Kingdom. They will continue to vote for Sinn Féin and the SDLP in elections because these parties are viewed as those who vie to look after their community’s interests. But that does not necessarily mean they want to cut all ties to the UK or sign up for a 32-county unitary republic.

“Ah!,” they say. “But hard Brexit!” This is the fourth point why Rodden and Rossi are wrong. They argue that a hard Brexit would necessitate a hard border with the imposition of frontier infrastructure, tolls, taxes, etc. Rodden and Rossi claim that “[t]he only workable plan for Brexit that will prevent a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic is for the north to stay in the EU customs area despite Brexit.”

This is simply not true. By now almost everyone has conceded, including civil servants in both London and Dublin, that even in the event of a No Deal Brexit (which has pretty much been ruled out) the technology already exists to provide a fairly seamless border. The few companies whose cross-border trade would fall into the relevant categories could be checked not at the border but electronically. While anti-Brexiteers spent months arguing that this was an impossible pipe dream, the number of researchers, customs agents, civil servants, and others who point out that the technology exists and has been used in similar scenarios for years is now so voluminous as to render the argument irrelevant.

(Rodden and Rossi are also entirely incorrect in claiming that Northern Ireland has adopted “quite restrictive” laws on “abortion and gay rights”. In fact, Northern Ireland’s post-1998 democratically elected representatives have mostly decided against taking action to change existing laws on these subjects even though they have been altered or repealed in England, Wales, and Scotland.)

There are other problems with the Rodden/Rossi economic determinist case for a united Ireland. For one thing, there is an economic determinist argument against it. The Republic of Ireland is a relatively prosperous country, though obviously not without its problems. Though romanticism and patriotism have deep roots, the Republic’s taxpayer base might balk at taking on the highly subsidy-reliant Northern Irish economy, even if only with a mind to transitioning it to a more free-market scenario.

Furthermore, sources in the Irish Defence Forces are quick to express their anguish at the army’s much diminished capacity even to carry out its existing commitments with the United Nations. Northern Ireland separating from the United Kingdom and joining the Republic would almost certainly spark a revival of violence amongst a minority of the province’s loyalists. Are voters in the Republic really that keen to take on an economic and counter-terrorist burden?

All this may sound a bit Cassandra-like, especially coming from a writer with traditional “Up Dev” Fianna Fáil sympathies, but these are all factors that need to be considered and which significantly inhibit the likelihood (completely separate from the wisdom) of Irish political unity in the near future.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Image: © HughJLF

Image: © HughJLF Image: © Stephen Benton

Image: © Stephen Benton Image: © Stephen Benton

Image: © Stephen Benton