About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

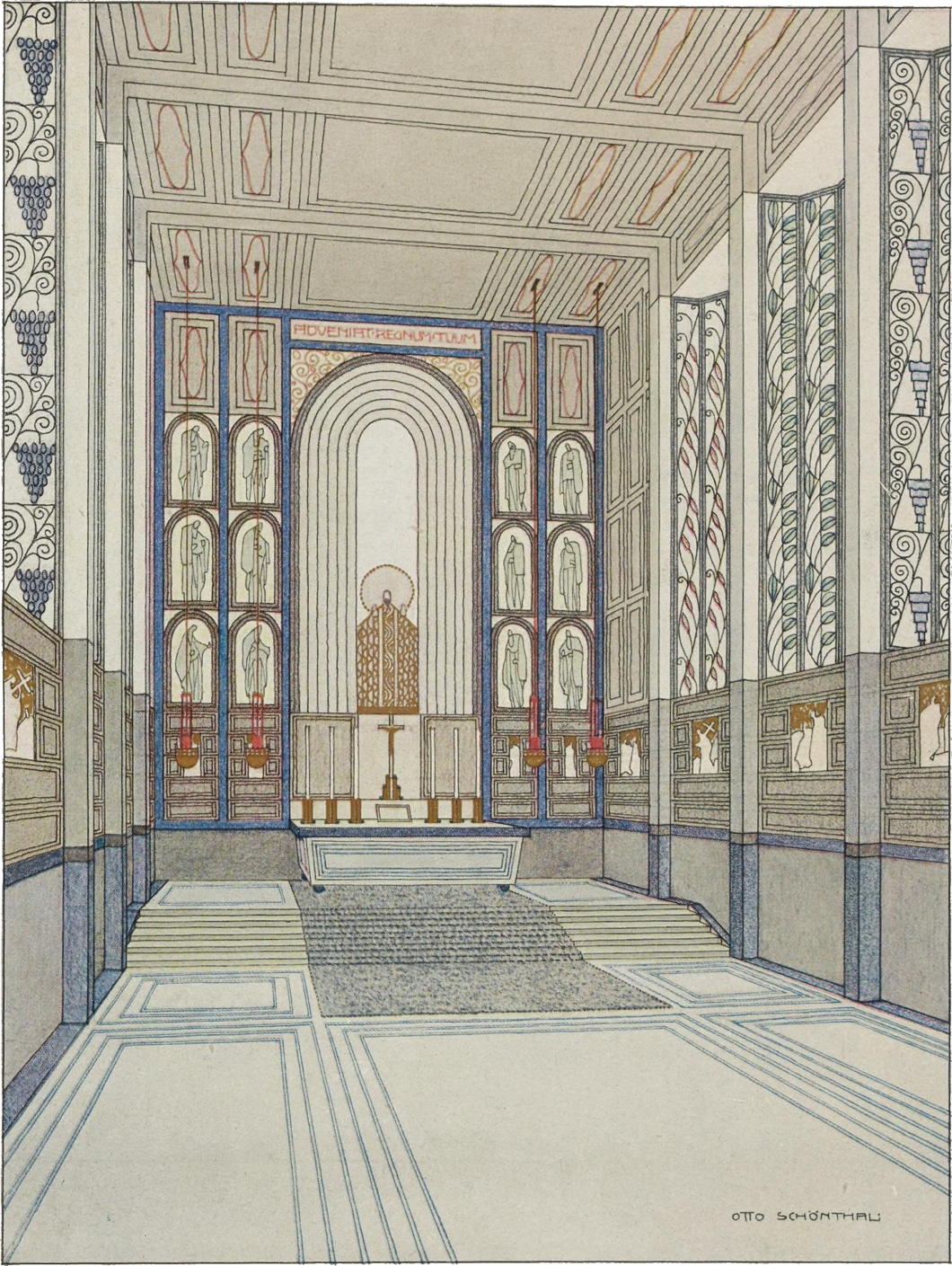

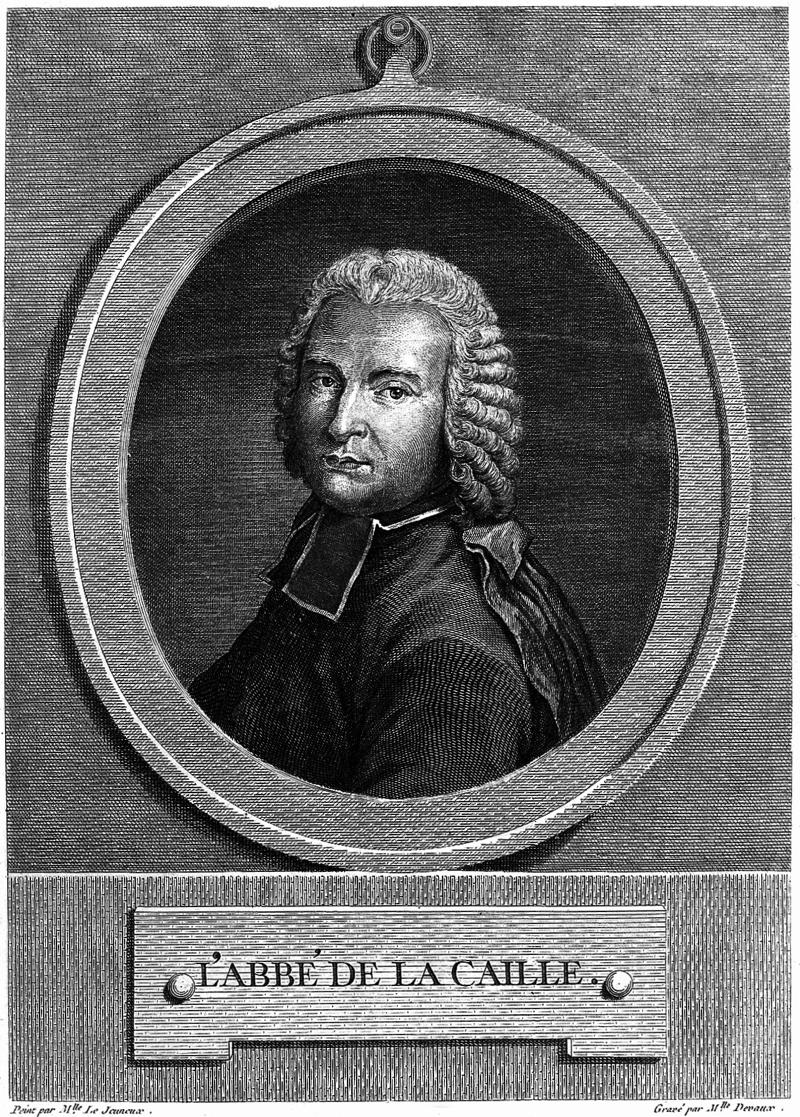

The Other Modern: Otto Schöntal

The Viennese architect Otto Schöntal was a student of Otto Wagner at the Academy of Fine Arts and exhibited this project for a Schloßkapelle in the periodical Moderne Bauformen in 1908.

It combines a simplicity of form with greater complexity in its decoration but like the work of many of the more mid-ranking architects of the Secession it comes across as a bit rigid and angular despite a certain freeness in its design.

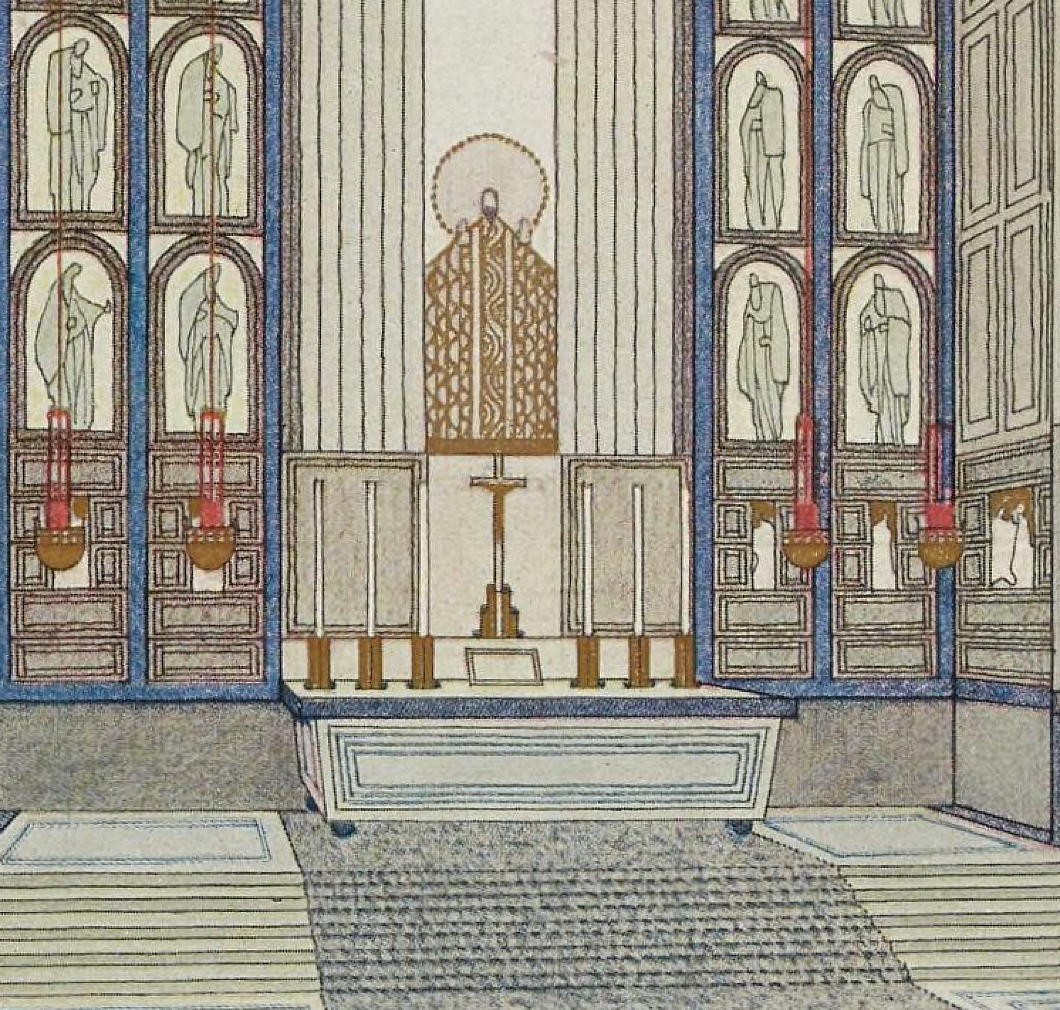

An African View of the Heavens

Catholic Clerical Skygazers at the Cape of Good Hope

In 1685, the Jesuit mathematician, astronomer, and not-quite-secret-agent Fr Guy Tachard stopped off at the Cape of Good Hope en route to Siam as an emissary of the Sun King, Louis XIV.

Given Dutch hostility both to the French and to Catholicism, Père Tachard was surprised by the generous welcome provided by the governor, Simon van der Stel. Tachard was allowed to set up an astronomical observatory in the Company’s Gardens (today Cape Town’s equivalent of Central Park). No sooner had this happened than the clandestine Catholics of the colony searched the priests out.

“Those who could not express themselves otherwise knelt and kissed our hands,” one of the expedition’s priests wrote. “In the mornings and evenings they came privately to us. There were some of all countries and of all conditions: free, slaves, French, Germans, Portuguese, Spaniards, Flemings, and Indians.”

Those who spoke French, Latin, Spanish, or Portuguese were lucky enough to have their confessions heard but one thing was absolutely forbidden: the Mass. The Dutch authorities would not permit Mass to be offered on land, and local inhabitants were forbidden from visiting the French ships.

Once, while the priests took ashore a microscope covered in beautiful Spanish gilt leather, locals suspected them of trafficking in the Blessed Sacrament such that the clerics were forced to demonstrate the use of the microscope to prove they were heeding the Governor’s instructions.

A century later another French cleric-astronomer, the Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, made his way to the Cape during Ryk Tulbagh’s time as Governor of the Dutch colony.

A century later another French cleric-astronomer, the Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille, made his way to the Cape during Ryk Tulbagh’s time as Governor of the Dutch colony.

As a mere deacon Lacaille could not offer the Mass and we know little of his relations with any remaining Catholics at the Cape.

There’s no doubt, however, that his contribution to astronomy while in South Africa was significant: Lacaille’s two years of astronomical observation there were prolific in their results. Of the 88 constellations currently recognised by the International Astronomical Union, fourteen were named by Lacaille — including the constellation Mensa (“table”) which took its name from the Latin for Cape Town’s Table Mountain.

Mensa remains the only constellation named after a feature on Earth, so there is a little bit of South Africa that is visible in the night sky anywhere south of the fifth parallel of the northern hemisphere.

A rood-stair pulpit

Among the features of the Church of All Saints in the Forest of Dean village of Staunton, Gloucestershire, is this fifteenth-century stone pulpit.

It is built into a rood-stair that once led to a wooden rood loft, demolished and removed some centuries ago.

This church also has a Norman font thought to have been hollowed out of an earlier square pagan Roman altar.

Pentonville Expressionism

When partner James Beazer of architectural firm Urban Mesh wanted to build an extension onto his Pentonville townhouse his tenderness towards brick expressionism took physical form.

“I love the work of the German Expressionists,” Beazer told the FT. “The playfulness of their use of brick. I think we’ve become uncomfortable with decoration today. Perhaps property has become too valuable. If it wasn’t, we’d all feel more able to take risks.”

Bringing brick expressionism down to a smaller scale produces interesting results here in Beazer’s case. It’s fun and somewhat slapdash — all the unconcerned confidence of an amateur delivered by a professional in his back garden. Hamburg meets the Shire in Islington.

I would have gently arched the windows, however, and the choice of lighting fixture is mundane. But it is a fundamental Cusackian principle never to let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

“I would probably have struggled to convince a client to do it,” Beazer says. But he has no confidence in the twisted brick add-on’s future once he moves house. “To be honest, the next people who move in will probably flatten it and replace it with a huge glass extension.”

The late Gavin Stamp gave an excellent lecture under the auspices of the Twentieth Century Society entitled ‘Hanseatic visions: brick architecture in northern Europe in the early twentieth century’.

It had been available online but now, alas, seems to be lost in the mists of time since the new incarnation of the Society’s website went up. Hope they stick it back online soon.

Articles of Note: 24.II.2021

• It is almost certain that we will never know who the actual winner of the 2020 presidential election was: the methods of fraud which might have been deployed are by their very nature ephemeral. Anton is right in that the best summary of the irregularities is from the U.S.-based Swedish academic Claes Ryn: How the 2020 Election Could Have Been Stolen. Ryn’s academic work is always an insightful read so his take here is worthwhile.

• I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: the Frenchman Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is always worth reading and always brings something to the table. P.E.G. argues the pre-Trumpers, anti-Trumpers, and never-Trumpers on the American centre-right need to recognise the reasons why Trump became a political phenomenon in the first place: Why Establishment Conservatives Still Miss the Point of Trump.

• One of the best books on urbanism in the Cusackian library is Allan Jacobs’s Great Streets. The expert work with its illustrative maps, diagrams, and line drawings is now a quarter-century old and on this anniversary Theo Mackey Pollack examines What Makes a Great Street.

• A new book argues that our vision of Northern Ireland as a corrupt and gerrymandered statelet from its birth in 1921 until the imposition of direct rule in 1972 is largely a myth. The editors Patrick J Roche and Brian Barton take to the pages of the once-great Irish Times to offer A Unionist History of Northern Ireland. It’s… an interesting perspective that will doubtless provoke a debate, but colour me sceptical.

Het Spui

Amsterdam is known for its canals, not its public squares, but Het Spui is quite welcoming all the same. The name means roughly sluice or floodgate, pointing to the unsurprisingly watery origins of the place.

At first, it was a canal like any other and was only filled in during the nineteenth century: The first part in 1867 when the neighbouring Nieuwezijds Achterburgwal was filled in, the rest in 1882, two years before the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal.

The Spui (pronounced “spouw” — unless Dawie van die bliksem corrects me) is a focal point surrounded by a number of sights. There’s the Old Lutheran Church, where the Maatschappij tot Nut van ’t Algemeen met in its early years and still a working congregation today.

There’s the Maagdenhuis, built as a Catholic orphanage and also the seat of the Archpriest of Holland and Zeeland until the restoration of the hierarchy in 1856. The orphanage moved out in 1957 when the building became a bank branch but was purchased by the University of Amsterdam in 1962 to house the administration of the growing institution. (more…)

The Three Flags of Uruguay

South America is a funnier place than most people expect and is full of odd curiosities. For example, most countries have one official name — e.g. ‘United States of America’ — whereas Argentina has three.

The 1853 constitution gives equal status to the names ‘United Provinces of the River Plate’, ‘Argentine Republic’, and ‘Argentine Confederation’, further detailing that ‘Argentine Nation’ should be used in the making and enactment of laws.

So far as I know, Argentina is also the only country whose name only comes in an adjectival form. We think of ‘Argentina’ as a noun, but it is actually an adjective — meaning silverine — that modifies ‘Republic’.

Referring to the country as ‘the Argentine’ was once fairly common, even predominant, in English but now seems a bit fogeyish. Nonetheless, it’s a more accurate translation.

While Argentina has three official names, today I learned that its smaller neighbour, the Oriental Republic of Uruguay, has three official flags.

Rather than add to the unceasing and useless repetition of the internet, I can happily link to the Danish vexillogist Anton Pihl who gives a useful and concise explanation and background to the three official flags of Uruguay.

Furthermore, Uruguay’s Artigas flag bears a great deal of similarity to the flag of the Argentine province of Entre Ríos which happens to sit right across the Uruguay river from Uruguay itself. The province’s name means ‘Between Rivers’ (the other river being the Paraná) which, of course, is a cognate of Mesopotamia far away.

And why is Uruguay the ‘Oriental Republic’? Because it’s the eastern bank of the Uruguay river.

The Perfect Home Garage

The Coach-House at Saasveld, Cape Town

With all of Suburbia working from impromptu home offices set up in their garages during Covidtide — presumably clinging to their space heaters at this time of year — the subject of the residential garage came up in conversation.

America, being a land of plenty, has the very worst and the very best of home garages. The best are, if a separate structure, often in an arts-and-crafts style and ideally with a floor above perfect for extra storage, conversion to a rental unit, or space for disgruntled teenagers. If attached to the house itself, it is to the side, and only one storey, so as not to distract attention.

The worst, however, are double wide and take up most of the facade, as well documented by McMansion Hell.

My perfect residential garage, however, is not in the States but from the Western Cape. Saasveld was the home of Baron William Ferdinand van Reede van Oudtshoorn, also 8th Baron Hunsdon in the Peerage of England.

In the 1790s, the Baron built the house on his Cape Town estate — between today’s Mount Nelson Hotel and the Laerskool Jan van Riebeeck. The elegant house and outbuildings were almost certainly the work of Louis Michel Thibault, the greatest architect of the Cape Classical style.

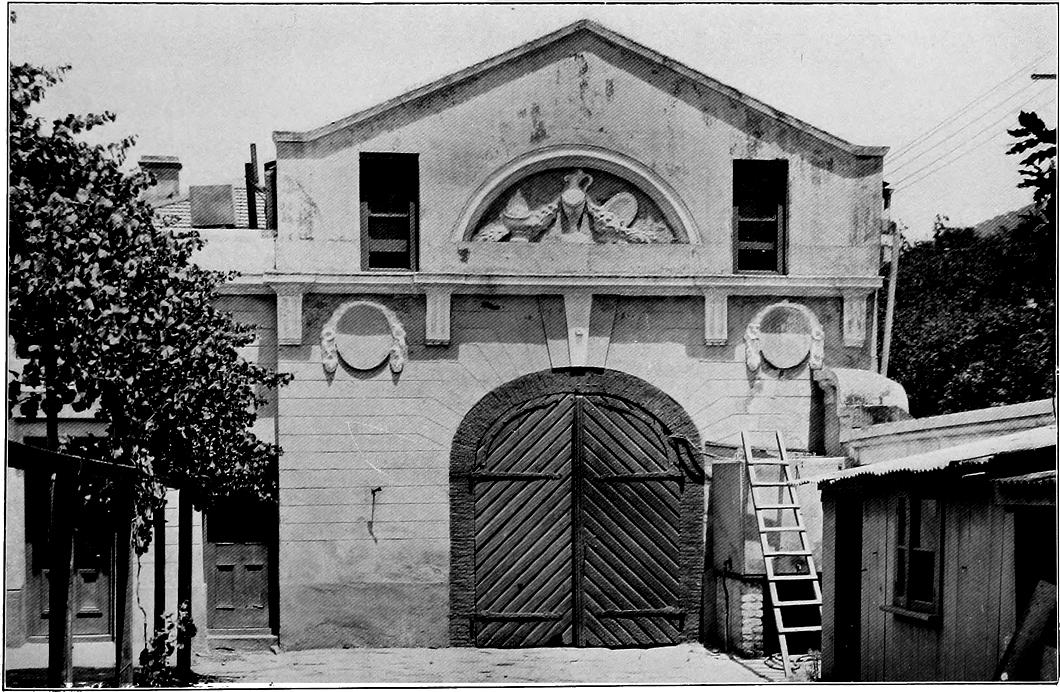

Behind the house were two flanking wine cellars linked by a colonnade, at least one of which (above) was eventually put to use as a coach house or garage and photographed by Arthur Elliott.

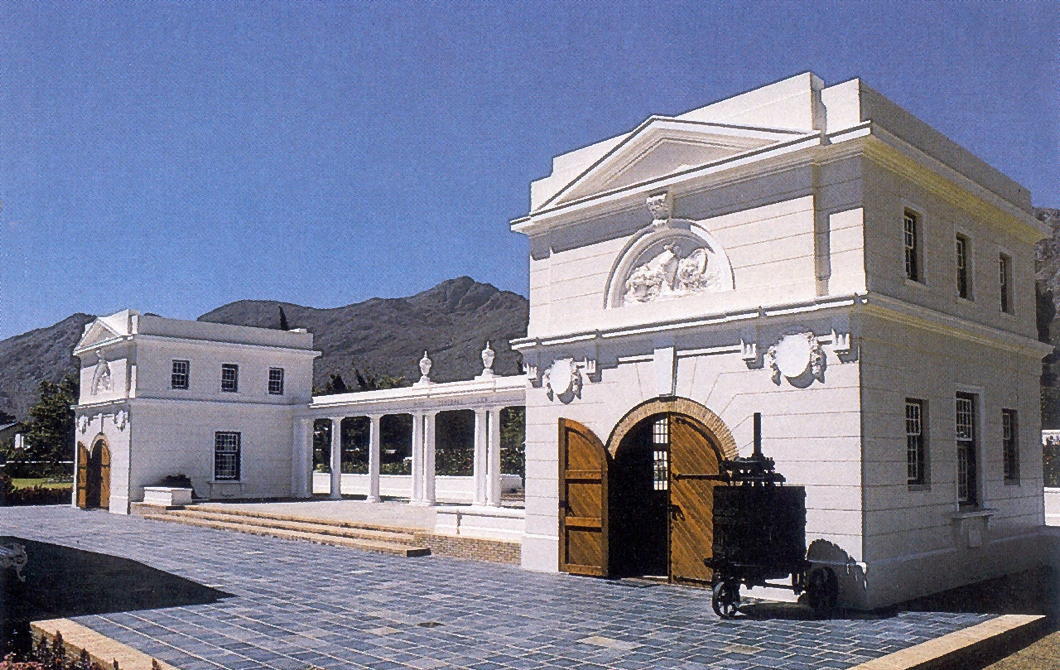

Unfortunately the house and its grounds fell into ruin and the Dutch Reformed Church bought the site for development and decided to demolish Saasveld. Architectural elements from the house were preserved and eventually re-assembled at Franschhoek where a reconstructed Saasveld serves as the Huguenot Memorial Museum today.

As Mijnheer van der Galiën reports, however, the tomb of William Ferdinand is still at the original site.

Here in Franschhoek the matching wine-cellars-turned-coach-houses are reproduced with their linking colonnade. And I still can’t help but think that — so long as you could fit a Land Rover through the doors — they would make the perfect home garage.

Staats Long Morris

Everyone knows about Gouverneur Morris, scion of one of New York’s great landowning families and given the moniker ‘penman of the Constitution’. As a signer of the Declaration of Independence his half-brother Lewis Morris III was a fellow ‘founding father’. Less well-remembered is his other half-brother Staats Long Morris (1728–1800).

Their father Lewis Morris II was the second lord of Morrisania, the feudal manor that covered most of what is now the South Bronx and has given its name to the smaller eponymous neighbourhood today.

Staats and Gouveneur owe their distinctive Christian names to the family names of their respective mothers.

Lewis II married Katrintje Staats who provided him with four children. After Katrintje died in 1730, Lewis married Sarah Gouverneur, daughter of the Amsterdam-born Isaac Gouverneur. Sarah’s uncle Abraham was Speaker of the General Assembly of the Province of New York, a role Lewis Morris II eventually filled.

Staats was born at Morrisania on 27 August 1728 and studied at Yale College in neighbouring Connecticut as well as serving as a lieutenant in New York’s provincial militia. He switched to the regular forces in 1755 when he obtained a commission as captain in the 50th Regiment of Foot, moving to the 36th in 1756.

Around that time Catherine, Duchess of Gordon, the somewhat eccentric widow of the third duke, was on the lookout for a second husband and Staats — though American, mere gentry, and ten years her junior — met with her approval. They were married in 1756 and Staats moved in to Gordon Castle to live as the Dowager Duchess’s husband.

‘He conducted himself in this new exaltation with so much moderation, affability, and friendship,’ a newspaper reported in 1781, ‘that the family soon forgot the degradation the Duchess had been guilty of by such a connexion, and received her spouse into their perfect favour and esteem.’

With the Duchess’s patronage, Lieutenant-Colonel Staats raised the 89th Regiment of Foot — “Morris’s Highlanders” — from the Scottish counties of Aberdeenshire and Banffshire though she was extremely cross when her new husband’s regiment was despatched to India where it took part in the siege of Pondichery.

In the event, Morris delayed following his regiment to India, leaving England in April 1762 and remaining there only until December 1763. When the young fourth Duke of Gordon came of age the following year, Staats turned his eyes to America and engaged in land speculation there. In 1768 he and the Duchess even went to visit their purchases in the new world, returning to Scotland in the summer of the following year.

With the fourth Duke’s help, and on the eve of the revolutionary stirrings in North America, Staats was elected to the British parliament for the Scottish seat of Elgin Burghs in 1774. He managed to hold on to it for the next ten years. Was this New Yorker the first Yale man to be elected to Parliament? I can’t find any before him, but more thorough research might prove fruitful.

In 1786 he inherited the manor of Morrisania but with the intervening separation between Great Britain and most of her Atlantic colonies General Morris thought it best to sell it on to his brother Gouverneur.

Though he had rejected a future in the world into which he had been born, Staats did return to North America in a professional capacity in 1797 when he was appointed governor of the military garrison at Quebec in what by then was Lower Canada.

Morris died there in January 1800, but his earthly remains were sent back to Britain where he was interred in Westminster Abbey — the only American to receive that honour.

Articles of Note: 15.I.2021

• Autumn and winter are a time for ghouls and ghosts and eery tales. At Boodle’s for dinner two or three years ago I sat next to the wife of a friend and exchanged favourite writers. I gave her the ‘Transylvanian Tolstoy’ Miklos Banffy, in exchange for which she introduced me to the English writer M.R. James — whose work I’ve immensely enjoyed diving into. The inestimable Niall Gooch writes about Christmas, Ghosts, and M.R. James, as well as pointing to Aris Roussinos on how Britons’ love for ghostly tales is a sign of (little-c) conservatism.

• There can be few figures in English history more ridiculous than Sir Oswald Mosley. But the Conservative MP who became a Labour government minister and then British fascist führer-in-waiting was also forceful in his condemnation of the savagery unleashed by the Black-and-Tans. In 1952 a local newspaper in Ireland announced that Sir Oswald and Lady Mosley “charmed with Ireland, its people, the tempo of its life, and its scenery” had taken up residence at Clonfert Palace in Co. Galway. “Sir Oswald,” the paper noted with amazing restraint, “was the former leader of a political movement in England.” Maurice Walsh presents us with the history of Mosley in Ireland.

• The death of the late Lord Sacks, Britain’s former Chief Rabbi, was the subject of much lament. Rabbi Sacks was obviously no Catholic, but his intellect, frankness, and generosity were much appreciated by Christians. Sohrab Ahmari, one of the editors at New York’s most ancient and venerable daily newspaper, offers a Catholic tribute to Jonathan Sacks.

• “Education, Education, Education” has become a mantra in the past quarter-century and while there is a point there’s also a certain error of mistaking the means to an end for the end itself. After all, in the 1930s Germany was the most and highest educated country in the world. At Tablet, probably America’s best Jewish magazine, Ashley K. Fernandes explores why so many doctors became Nazis.

• Fifty years ago the great people of the state of New York rejected both the Republican incumbent and a Democratic challenger to elect the third-party Conservative candidate James Buckley as the Empire State’s senator in Washington. At National Review Jack Fowler tells the gleeful story of the unique circumstances that brought about this victory for Knickerbocker Toryism and how Mr Buckley went to the Senate.

Benedict of Palermo

The island of Sicily is a cross-section of the numerous kingdoms and empires which have ruled and inhabited it from the Phoenecians down to the present day. During the Norman conquest of the island — those Normans did get around — many Lombards came to help secure the Normans’ rule over the existing Sicilians who were mostly Greek and Arab. The Gallo-Italic dialect of those Lombards is still spoken in a few towns and villages speckled across the island and the settlements they founded are known as the Oppida Lombardorum.

In one such Lombard town, San Fratello, in the 1520s a son was born to an enslaved couple named Cristoforo and Diana whose piety was so highly regarded that their master granted this first-born son, Benedetto (Benedict), his freedom from birth.

From his earliest days Benedict was prone to solitude to the extent that he was mocked by his peers, in addition to being insulted frequently for his black skin. As a teenager he left the family home and became a shepherd but gave whatever he could to help the poor and those even less fortunate than him.

Discerning the call to solitude, Benedict entered the hermitage of Santa Domenica in Caronia but his reputation for holiness was such that the pious people of the island began to visit him and implore him for his prayers and miracles.

Accompanied by another member of the community, Benedict fled to other places around the island, offering great and severe penances in reparation for the sins of humanity, but no matter where he went within days the faithful had found out and pestered him.

When the founder of the hermetic community at Santa Domenica died, the brothers elected Benedict his successor, despite his lack of education and illiteracy. Benedict returned to lead the community until it was abolished in 1562 by the reforms of Pope Pius IV who urged independent groups of Francis-inspired hermits to regularise themselves into existing Franciscan orders.

Benedict went first to a Franciscan friary in Giuliana before settling into that of Santa Maria di Gesù in Palermo, the primary city of Sicily. Having been a superior of his old community, Benedict arrived at the Palermo community as a simple cook but even here his piety and talents were recognised. He was first put in charge of the novices and then, in 1578, his confrères elected him their custos or superior though he was only a brother rather than a priest.

He was known as a miracleworker across the island, but it was not only the poor, the sick, and the destitute who flocked to Benedict to seek his help. Theologians and men of learning came to visit this humble and uneducated friar. Even the viceroy of the island was known to take his counsel on important affairs of state.

In his later years, Benedict returned to being the cook of the friary until his death in April 1589. By that time the whole island of Sicily — Greeks, Arabs, Latins, all — revered this poor, humble, and unlettered friar.

Sicily’s ruler, King Philip III of Spain, ordered a magnificent tomb to be built to house Benedict’s remains in the friary of Santa Maria di Gesù, and in death his cult spread far beyond the island.

St Benedict of Palermo — or Benedict the Moor — was beatified by Benedict XIV in 1743 and canonised by Pius VII in 1807. Over the centuries, many non-white Christians came to implore his intercession and he became particularly popular among natives and mixed-race peoples in South America, in Africa itself, and amongst African-Americans in the United States.

This statue is believed to be the work of the Sevillian sculptor José Montes de Oca and was carved in the 1730s. Long in a private collection in Milan, since 2010 it has formed part of the collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The Green Mountain Flag

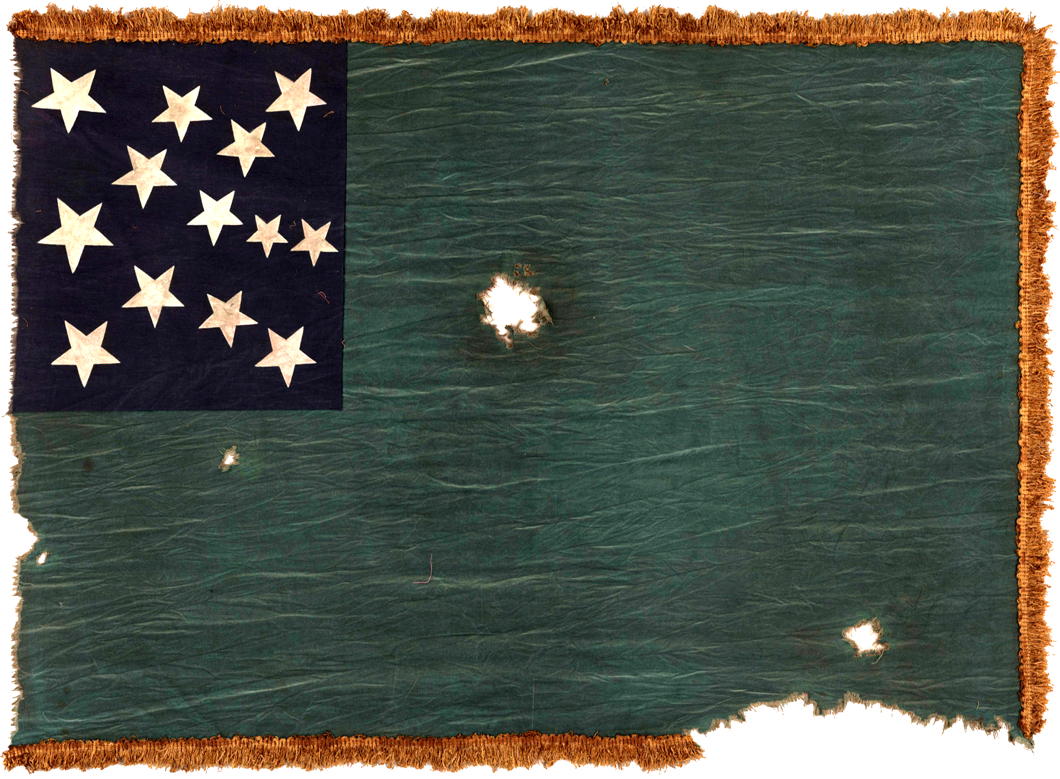

One of my favourite American flags is the war flag of the State of Vermont, better known as the banner of the Green Mountain Boys. The Boys were a ragtag militia founded in 1770 to prevent the encroachments by the Province of New York upon what was then known as the New Hampshire Grants — land west of the Connecticut River that was claimed by both New York and New Hampshire.

The dispute between the two was eventually settled in favour of a third party: the state of Vermont which declared its independence in 1777 (as the Republic of New Connecticut) and in 1791 was the first state to be admitted to the Union that was not one of the original thirteen colonies.

During the Revolution, the Green Mountain Boys fought under Ethan Allen and at the Battle of Bennington they marched under a green flag with a blue canton bedecked with thirteen stars. The canton of this original flag still survives at the Bennington Museum.

While Vermont’s state flag has undergone a variety of transformations, the state has preserved the Green Mountain Flag as its war flag, used by both the Army and Air components of the Vermont National Guard and the Vermont State Guard.

The flag is also popular amongst supporters of Vermont’s reclaiming its independence, an issue explored by Vermont Public Radio as well as in a book by Bill McKibben and a collection of essays.

The Galloway Cross

What could be better than a hoard — and a Kircudbrightshire hoard at that? Sometime during the tenth century, a gentleman decided to deposit an interesting array of objects in Galloway only for them to be rediscovered by a metal detectorist in 2014.

Thus have come to us the Galloway Hoard, a collection of objects the most important of which is this pectoral cross made of silver and decorated with symbols of the four evangelists: the eagle of John, the ox of Luke, the angel of Matthew, and the lion of Mark.

As the hoard was buried when Kircudbrightshire was part of Northumbria — before the area became Scottish — the art has been identified as Anglo-Saxon from the age of the Vikings. My theory is an expert thief was at work, nicking precious objects from hapless victims — an armband gives the name of one poor Egbert in runes.

“The pectoral cross, with its subtle decoration of evangelist symbols and foliage, glittering gold and black inlays, and its delicately coiled chain, is an outstanding example of the Anglo-Saxon goldsmith’s art,” Dr Leslie Webster, an expert, said. “It was made in Northumbria in the later ninth century for a high-ranking cleric, as the distinctive form of the cross suggests.”

The Galloway Cross, before cleaning and conservation

All treasure found in Scotland must be reported to the Queen’s and Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer who in 2017 determined the hoard’s value at £1.8 million. Scots law allows the discoverer to keep the full value of the hoard if there is no owner, though as it was found on glebelands belonging to the Church of Scotland that body’s General Trustees demanded a cut as well.

The objects themselves have found a home in the National Museum of Scotland who will be exhibiting them from February until May when they will go on tour to Aberdeen and Dundee.

Septuagesimo Uno

Septuagesimo Uno is often believed to be the smallest park under the purview of the Parks Department of the City of New York. It’s not. (By my reckoning, the Abe Lebewohl Triangle where Stuyvesant Street meets 10th Street near St-Mark’s-in-the-Bowery is the smallest.)

Though not the smallest, this park on West 71st Street is charming all the same. The site was acquired in 1969 thanks to Mayor Lindsay (or “Lindsley” as my maternal great-grandfather always mispronounced his name) and his Vest Pocket Park initiative. The small building on the lot was condemned and demolished by the City though it was only handed over to the Parks Department in 1981.

Originally known as the “71st Street Plot”, Parks Commissioner Henry Stern thought the name was too boring so rechristened it under the Latin moniker Septuagesimo Uno — Latin for ‘seventy-one’. (more…)

A Scene in Buenos Aires

A hatted woman sits on a balcony, looking away out over the Plaza de Mayo, the Cathedral of Buenos Aires, and the city beyond.

It looks like the sort of thing taken by one of the French photographers, but in fact it is by a total amateur: Henry Dart Greene, the son of the Californian architect Henry Mather Greene (of Greene & Greene).

From 1928 to 1931, Dart Greene worked for the Argentine Fruit Distributors Company, founded by the Southern Railway to make use of the individual smallholdings long its line.

Upon his death, Dart Greene’s papers were deposited in the library of the University of California at Davis including this photograph from his time in Argentina.

While the building it’s taken from has been demolished and replaced with a bank, most of what you see beyond is still there.

Articles of Note: 23.XI.2020

• France’s Year of de Gaulle has marked the fiftieth anniversary of his death earlier this month and what would have been the general’s one-hundred-and-thirtieth birthday yesterday. Julien Nourian has put together a Weberian analysis of the general and his charismatic mystique.

• President Trump is a very different kind of leader to de Gaulle, and his chances of continuing in the White House are not looking great at the moment. (Our head of legal in New York thinks he’s still got a chance, however.)

Regardless of who will be inaugurated in January of next year, Trump managed to win the highest proportion of minority votes of any Republican candidate since 1960 (when the GOP choice was a member of the NAACP). Meanwhile, Trump lost votes among old, white, well-to-do men.

What is the future of American political conservatism? Ben Hachten points out It’s Not Your Father’s GOP.

New England poli-sci professor Darel E. Paul explores The Future of Conservative Populism, pointing out the big increase in the Hispanic vote for Trump — especially Hispanics living in Texas along the Mexican border.

• In Britain, Ferdie Rous says the Conservative party is having difficulty reconciling the business wing of the party with our rural roots, but suggests that The writings of Lewis and Tolkien embody conservative environmentalism.

Meanwhile David Skelton asserts It was working class voters who delivered this majority – and Johnson must not abandon them now.

• Here in London we’re still in the middle of the second lockdown. Instead of following the science, governments around the world are implementing the exact opposite of effective measures to combat the pandemic. It’s The Greatest Scandal of Our Lifetime according to R.J. Quinn.

• We can always do a with a dose of Metternich and Wolfram Siemann’s 900-page doorstop has provided a chance for many to analyse the master diplomat. Ferdinand Mount examines The Prime Minister of the World.

• And finally, the Museum of Literature Ireland features an online exhibition on the American writer, speaker, reformer, and statesman Frederick Douglass’s visit to Ireland 175 years ago. (Available as Gaeilge too.)

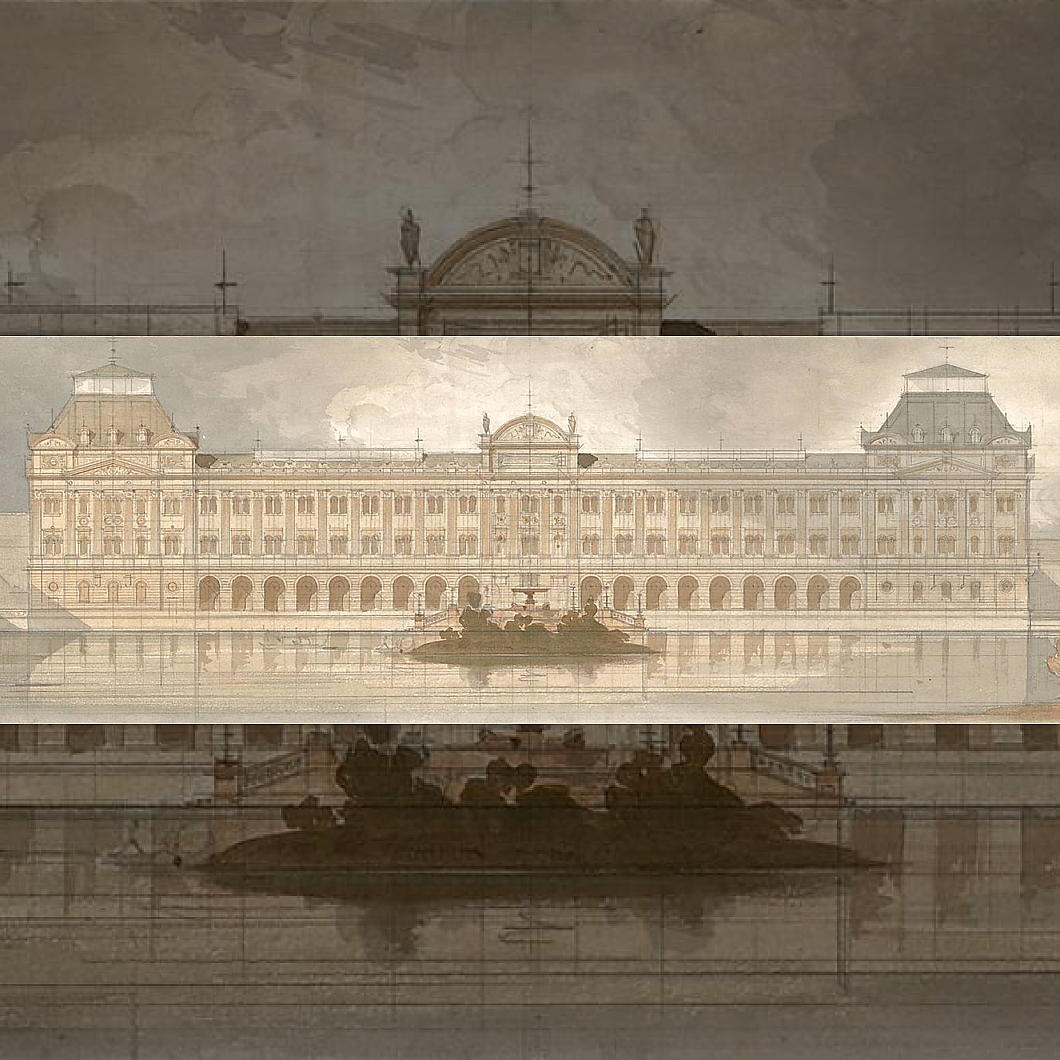

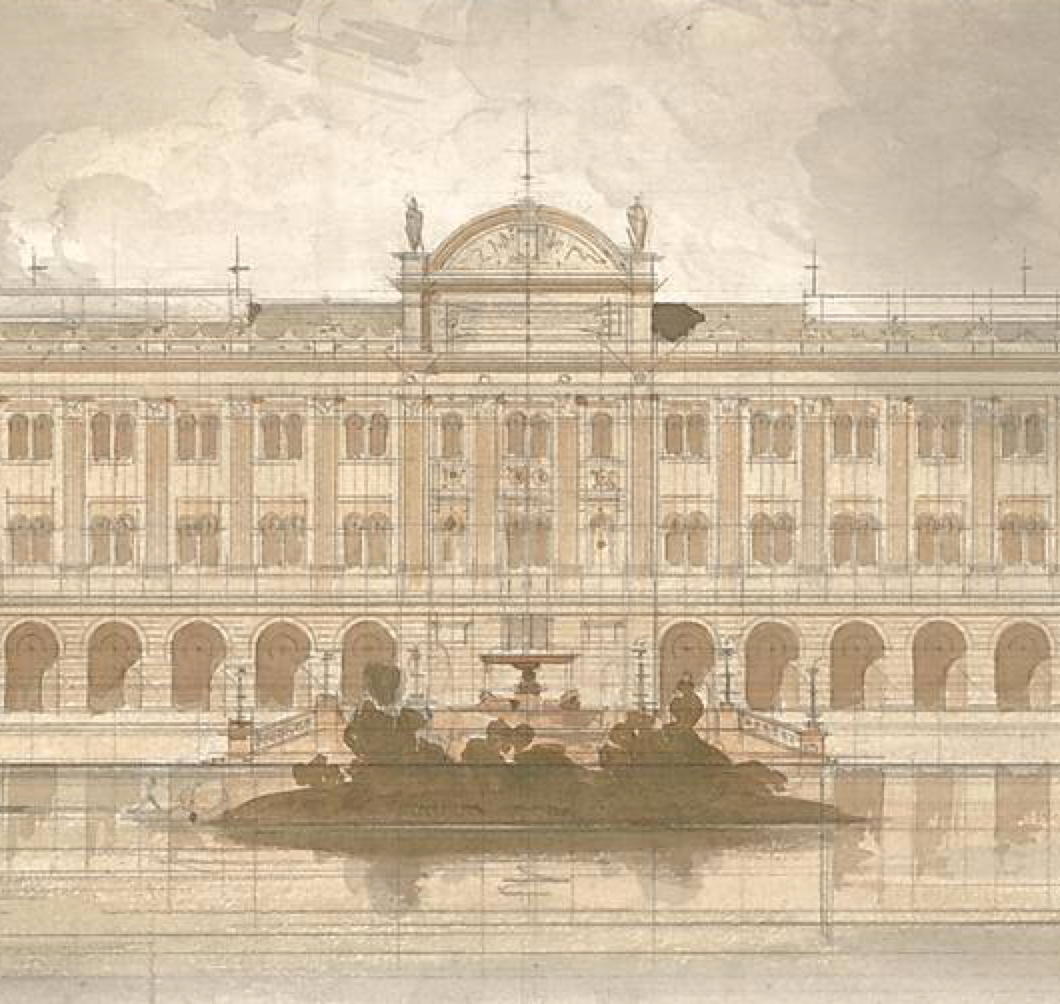

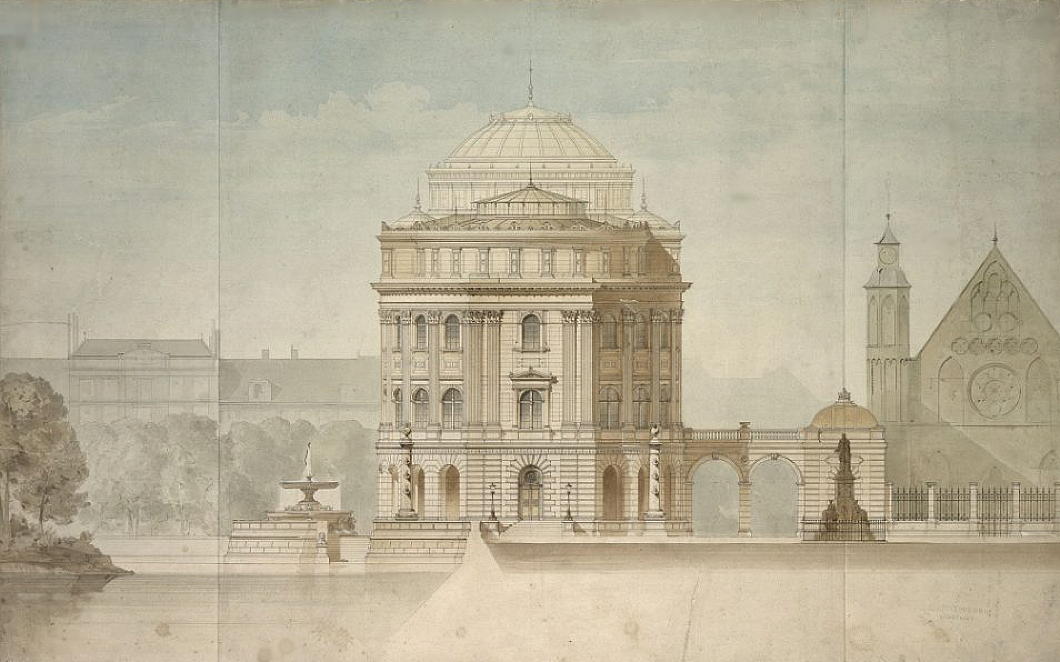

A Palace for the States-General

A Palace for the States-General

The nineteenth century was the great age for building parliaments. Westminster, Budapest, and Washington are the most memorable examples from this era, but numerous other examples great and small abound in Europe and beyond.

The States-General of the Netherlands missed out on this building trend, perhaps more surprisingly so given their cramped quarters in the Binnenhof palace of the Hague. The Senate was stuck in the plenary chamber of the States-Provincial of South Holland with whom it had to share, while the Tweede Kamer struggled with a cold, tight chamber with poor acoustics.

The liberal leader Johan Rudolph Thorbecke who pushed through the 1848 reforms to the Dutch constitution thought the newly empowered parliament deserved a building to match, and produced a design by Ludwig Lange of Bavaria. All the Binnenhof buildings on the Hofvijver side would be demolished and replaced by a great classical palace.

Despite members of parliament’s continual complaints about their working conditions, Thorbecke and Lange’s plans were vigorously and successfully opposed by conservatives. As the academic Diederik Smit has written,

A large part of the MPs was of the opinion that such an imposing and monumental palace did not fit well with the political situation in the Netherlands. […] In the case of housing the Dutch parliament, professionalism and modesty continued to be paramount, or so was the idea.

In fact, as Smit points out, significant alterations were made to the Binnenhof, like the demolition of the old Interior Ministry buildings by the Hofvijver, but these were replaced with structures that were actually quite historically convincing.

Further plans were drawn up in the 1920s — including a scheme by Berlage — but MPs felt that none of the proposals quite got things right and they were shelved accordingly. It wasn’t til the 1960s that the lack of space and the poor conditions in the lower chamber forced action. All the same, efficiency was the order of the day, as the speaker, Vondeling, made clear: “It is not the intention to create anything beautiful”.

Even then it wasn’t until the 1980s that the work was started, and the MPs moved into their new chamber in 1992. As you can see in this photograph, Vondeling’s aim of avoiding anything beautiful or showy has been achieved. The new chamber is certainly spacious — indeed some MPs claim it is too spacious. The art historian and D66 party leader Alexander Pechtold pointed out the distance between MPs inhibits real debate, unlike in the British House of Commons, and to that extent parliamentary design is inhibiting real democracy.

Battledore and Shuttlecock

Is this the earliest-known depiction of badminton in art?

Apparently not, as the sporting accoutrements depicted herein are of the much older game of Battledore and Shuttlecock — an antecedent of badminton.

It was painted by William Williams, the sailor, writer, and painter born in Bristol in 1727 and shipwrecked in the Caribbean before living in Philadelphia.

While the subject is uncertain, he is believed to be a boy of the Crossfield family, for whom it is known that Williams had depicted other young family members.

Since 1965 it has been in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum but is not currently on view.

Williams was also the author of what is arguably the first American novel — The Journal of Llewellin Penrose, Seaman — though he couldn’t find a publisher so it was only printed in 1815 nearly a quarter century after his death.

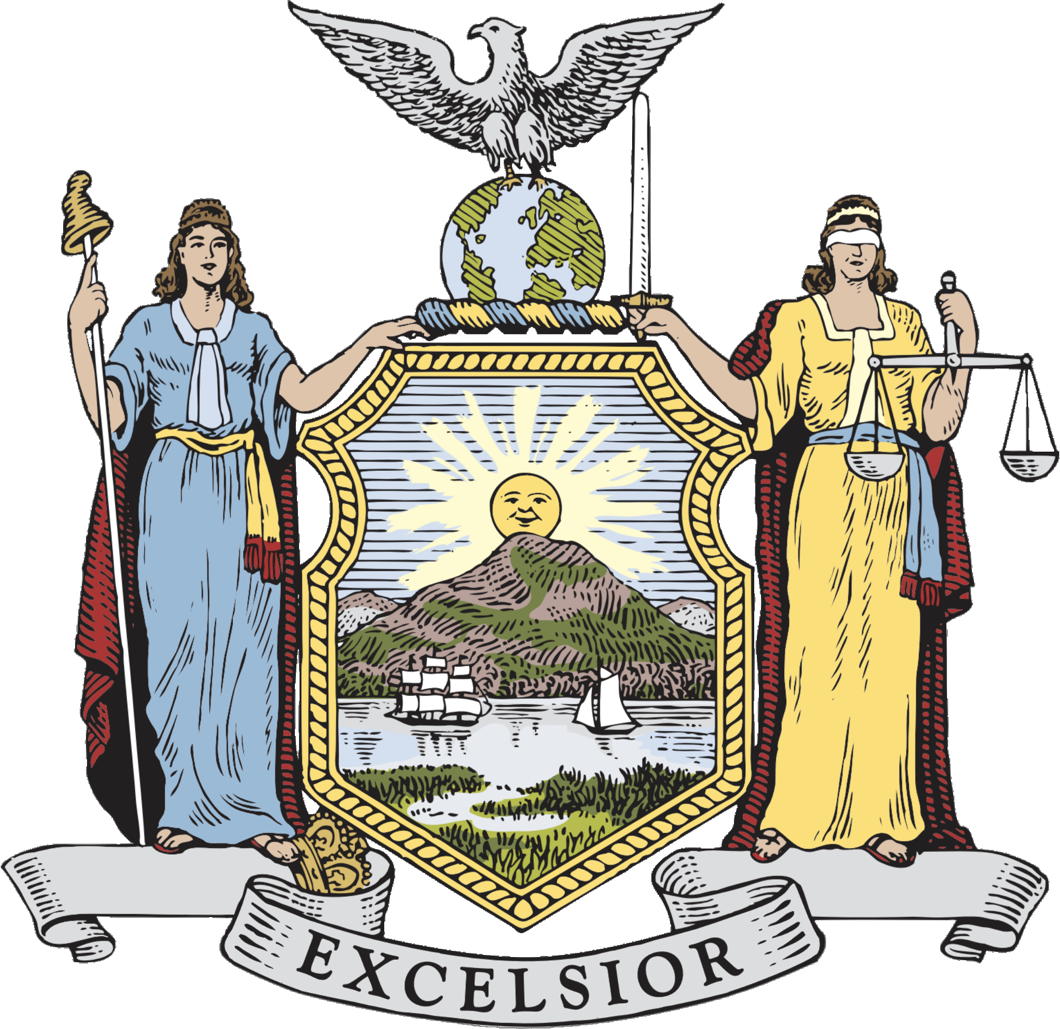

Arms and the Man

GOVERNOR CUOMO — is there anything that man won’t fiddle with? Is there nothing that can escape his grasping hands? Are we to suffer from the incessant interference of this megalomaniac forever?

The latest trespass His Excellency has committed is to encroach upon the very sacred symbols of the Empire State itself: our beloved coat of arms — and, by extension, the flag which also bears it aloft.

Gaze upon its beauty, for you will see it fade. Azure, in a landscape, the sun in fess, rising in splendour or, behind a range of three mountains, the middle one the highest; in base a ship and sloop under sail, passing and about to meet on a river.

This beautiful device was adopted by the very first Assembly and Senate of the State of New York back in 1778, having been designed a year earlier. It has remained substantially unchanged since the 1880s until Governor Cuomo in one of his fits of fancy decided to sneak a change via the state budget, of all things.

“In this term of turmoil, let New York state remind the nation of who we are,” Governor Cuomo said in his State of the State address in January of this year. “Let’s add ‘E pluribus unum’ to the seal of our state and proclaim at this time the simple truth that without unity, we are nothing.”

Why the national motto should be interjected into the state flag when we have our own motto is beyond me. Rather than introduce a bill that would allow an open debate on the matter, the Governor decided to sneak it into the state budget. This passed in April, so the coat of arms, great seal, and flag of the state of New York have all now been altered to include the superfluous words.

That said, I have a sneaking suspicion the change might be honoured more in the breach than in the observance. Flag companies doubtless have a large back supply of pre-Cuomo flags to shift and customers are rarely up to date on matters vexillological and heraldic. I suspect that the next time you float down Park Avenue and see the giant banners fluttering from corporate headquarters very few will have updated their state flag.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories