2023 July

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

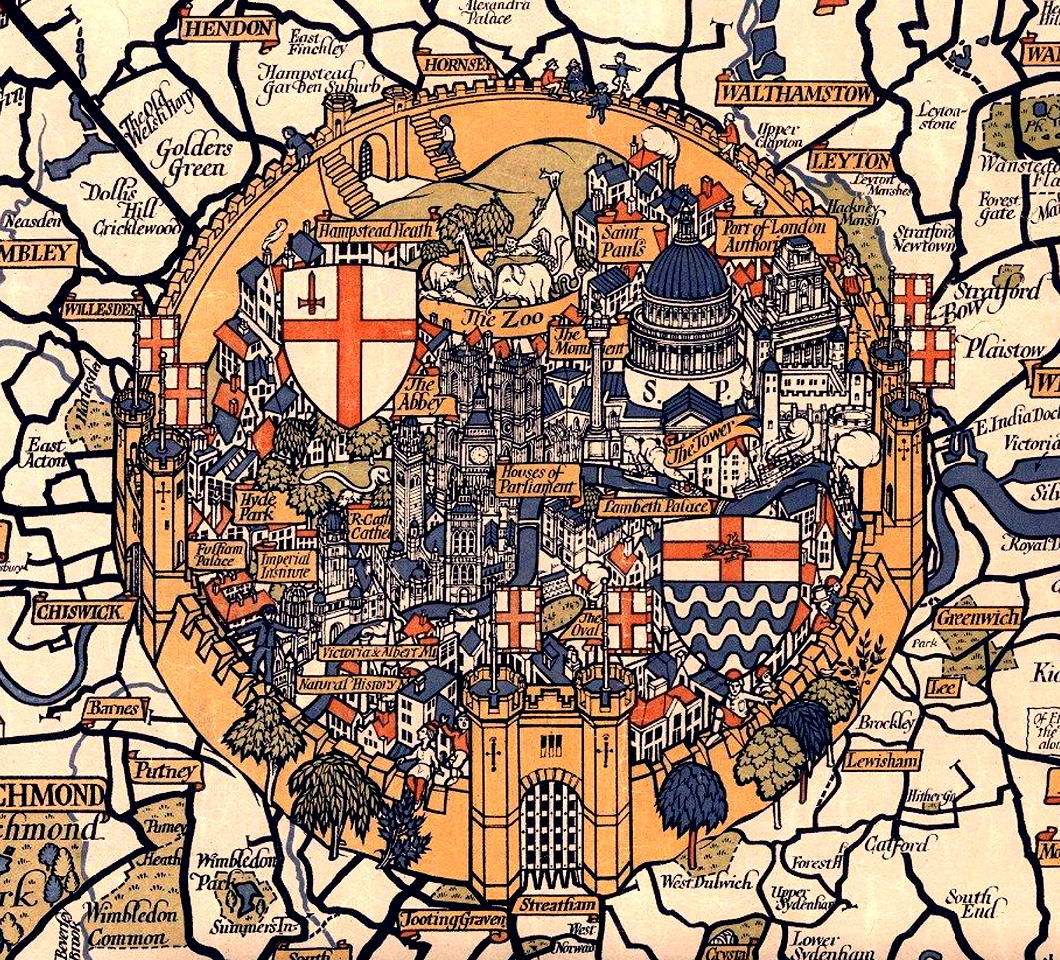

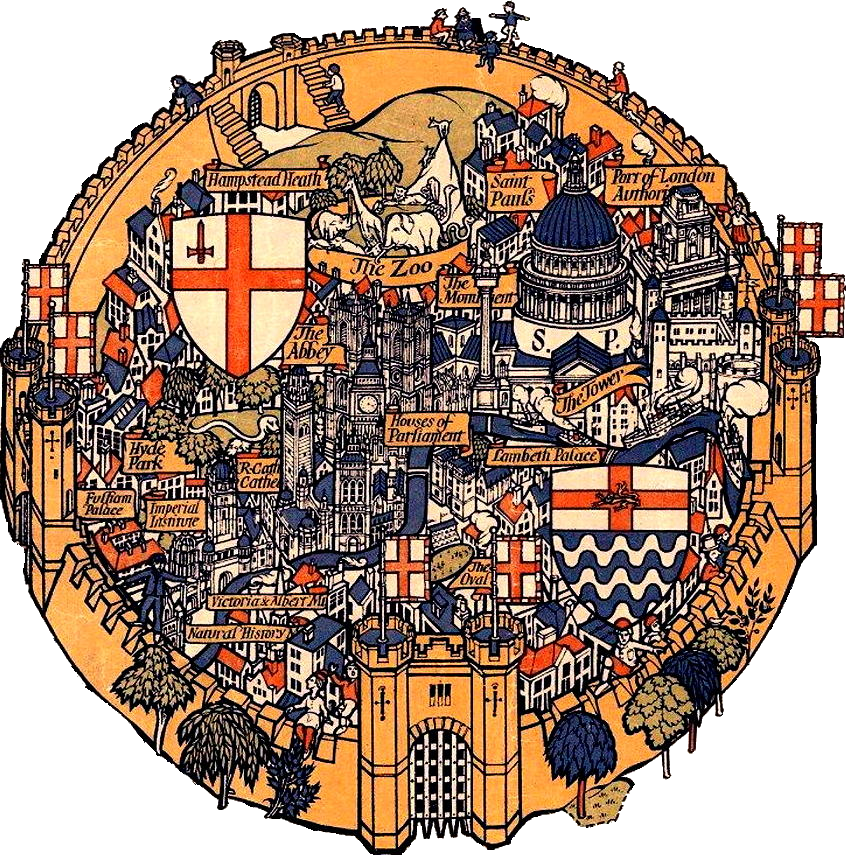

Fortress London

What could be more mundane than the Country Bus Services Map? Not when you put the design in the hands of Max Gill. Younger brother to the more famous (but controversial) Eric Gill, Lesilei Macdonald “Max” Gill was a polymathic artist: cartographer, designer, sculptor, painter, and letterer.

In 1914, Frank Pick, inventor of the London Underground brand, hired Max Gill to create the Wonderground Map. Each Underground station had a copy of this map with its inventive and amusing illustrations, such as the two figures hurling hams at Hurlingham. As one newspaper said when it was introduced, ‘People spend so long looking at this map – they miss their trains yet go on smiling.’

The Country Bus Services Map dates from 1928 and depicts London as a great crammed and crowded fortress city from which bus services flow forth to allow the citizens to escape its walls and experience the rustic beauty of the surrounding countryside.

St Paul’s Cathedral looms large between shields depicting the arms of the City and County of London, with the Monument, the Port of London Authority, and the Tower cuddling up to it.

Lambeth Palace and the Oval at Kennington are the only features south of the river that make it into Gill’s walled metropolis.

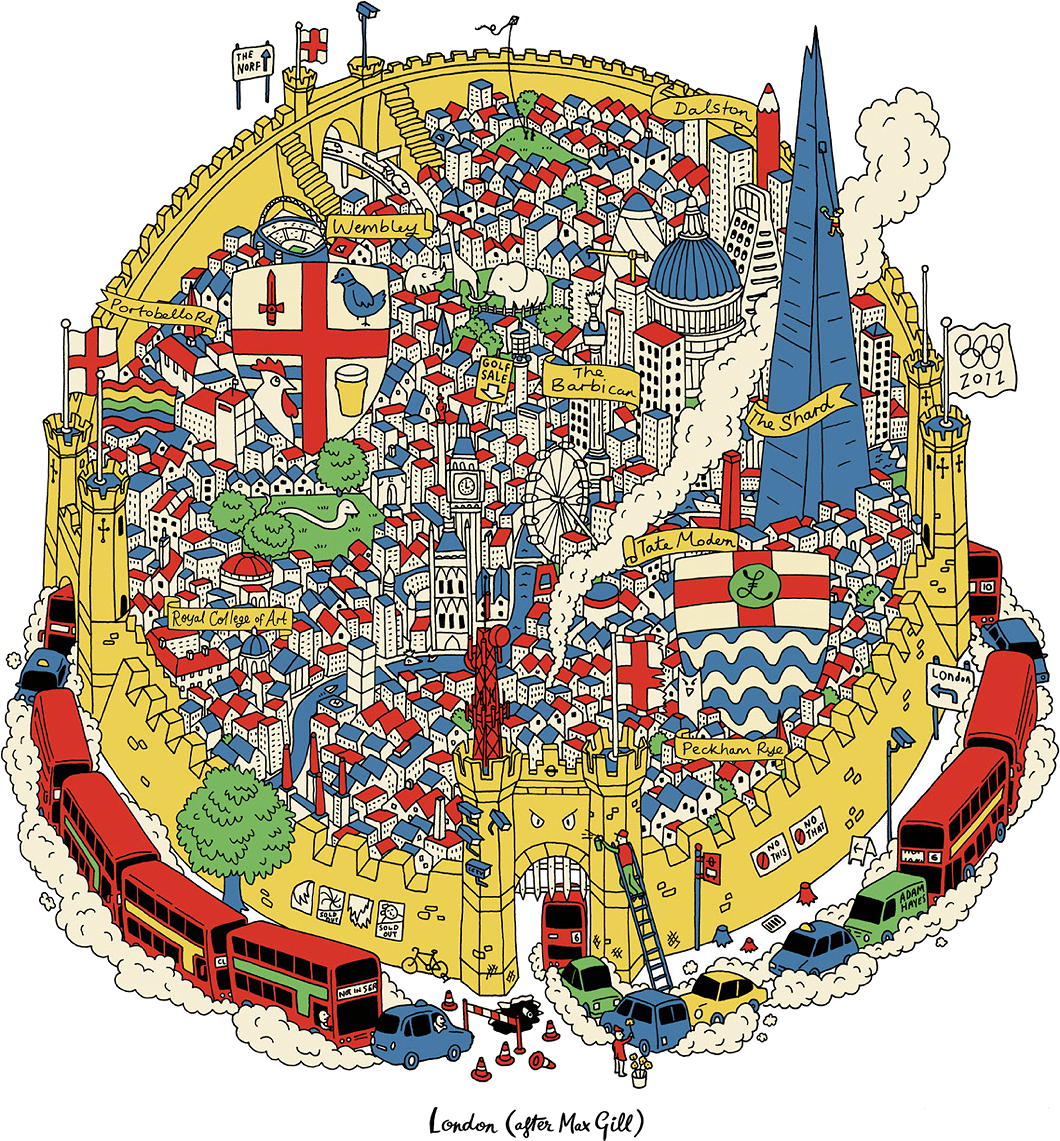

In more recent years, the designer and typographer Adam Hayes decided to issue a cheeky update entitled ‘London (After Max Gill)’ (available as a print as well).

Choked by smoggy traffic, the Shard now looms large, while a cheese grater represents the Cheesegrater. Tree stumps are joined by fussy signs instructing NO THIS and NO THAT and CCTV cameras are omnipresent.

‘Wonderground’ and the Country Bus Services Map were not the limits of Max Gill’s work for London Underground. The London Transport Museum holds many examples of his work within there collection, some of which have been digitised and are viewable online — though irritatingly not in any sufficiently zoomable detail.

St Paul’s: Before and After the War

Wren’s post-Fire St Paul’s Cathedral was an icon of resistance to German aggression and an emblem of survival during the Blitz, but while the dome survived the church did suffer damage: A bomb fell threw the roof of the east end on the evening of 10 October 1940, tumbling masonry and destroying the high altar.

Despite the reredos remaining largely intact, as can be seen in the photograph above, it was decided to remove it and rebuild the High Altar under a baldacchino as Sir Christopher Wren had intended.

In 1958 the new High Altar, designed by W Godfrey Allen and Steven Dykes Bower, was dedicated with an American Memorial Chapel behind it.

This was proposed by the Dean of St Paul’s and General Eisenhower volunteered to raise money for it in the United States.

The Dean turned down the Supreme Commander’s offer, saying that this would be paid for by Britons as an appreciation of the American sacrifice during our common struggle.

A roll of honour lists the names of the 28,000 Americans who gave their lives while stationed from Great Britain.

Perhaps more intriguing than either view is the one below of the interior of St Paul’s before the Victorian scheme for the High Altar was executed.

The Ukrainians’ Secret Weapon

For those looking for an explanation as to the notable success of the Ukrainians on the battlefield in the current unpleasantness taking place in their country, look no further.

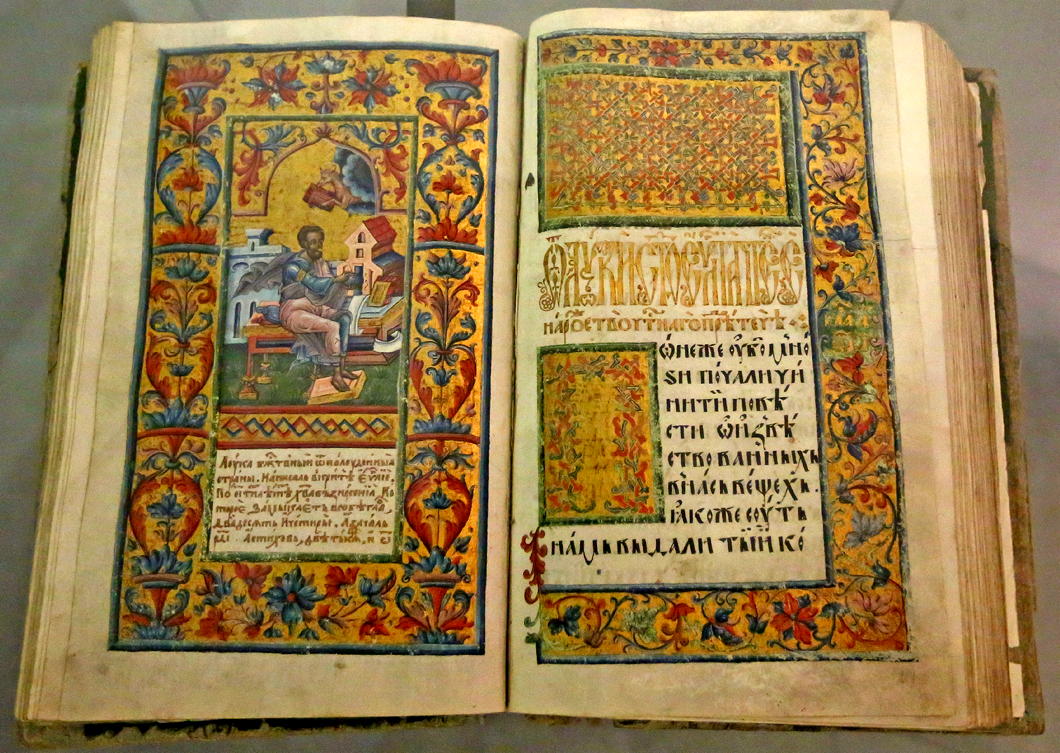

In a thread of tweets, the biblophile Incunabula reveals the Ukraine’s secret weapon: the Peresopnytsia Gospels (Пересопницьке Євангеліє).

“All six Ukrainian Presidents since 1991,” Incunabula writes, “including Volodymyr Zelensky, have taken the oath of office on this book: the sixteenth-century Peresopnytsia Gospels, one of the most remarkably illuminated of all surviving East Slavic manuscripts.”

“The Peresopnytsia Gospels were written between 15 August 1556 and 29 August 1561, at the Monastery of the Holy Trinity in Iziaslav, and the Monastery of the Mother of God in Peresopnytsia, Volyn.”

“This manuscript is the earliest complete surviving example of a vernacular Old Ukrainian translation of the Gospels. Its richly ornamented miniatures belong to the very highest achievements of the artistic tradition of the Ukrainian and Eastern Slavonic icon school.”

“The Peresopnytsya Gospels were commissioned in 1556 by Princess Nastacia Yuriyivna Zheslavska-Holshanska of Volyn, and her daughter and her son-in-law, Yevdokiya and Ivan Fedorovych Czartoryski. After its completion the book was kept in the Peresopnytsya Monastery.” (more…)

Irving’s Sunnyside

From the Westchester Herald (as reprinted in the Times of London, 24 April 1835):

On the premises just mentioned there is still standing an old stone house, built in the ancient Dutch style of architecture, during the French war, by Wolfred Acker, and afterwards purchased by Van Tassel, one at least of whose descendants has been immortalized in story by the racy pen of its present gifted proprietor.

It is the identical house at which was assembled the memorable tea-party, described in the legend of Sleepy Hollow, on that disastrous night when the ill-starred Ichabod was rejected by the fair Katrina, and also encountered the fearful companionship of Brom Bones in the character of the headless Hessian.

The characters in this delectable drama are mostly known to our readers; but time, that tells all tales, enables us to add one item more, which is, that the original of the sagacious schoolmaster was not the individual generally considered as such, who still resides in this country, but Jesse Martin, a gentleman who bore the birchen sway at the period of which the legend speaks, and who afterwards removed further up the Hudson, and is since deceased.

The location is a most delightfully secluded spot, eminently suited to the musings and mastery of mind; and it is the design of the proprietor, without changing the style or aspect of the premises, to put them in complete repair, and occupy them as a place of retirement and repose from the business and bustle of the world.

Special Mission to Rome

RELATIONS BETWEEN THE Court of St James’s and the Holy See have evolved in the many centuries since the Henrician usurpation. At times, such as during the Napoleonic unpleasantness, the interests of London and the Vatican were very closely aligned — despite the lack of full formal diplomatic relations. Later in the nineteenth century Lord Odo Russell was assigned to the British legation in Florence but resided at Rome as an unofficial envoy to the Pope.

It wasn’t until 1914 that the United Kingdom sent a formal mission to the Vatican, but this was a unique and un-reciprocated diplomatic endeavour — a full exchange of ambassadors would have to wait until 1982. (Until then, the Pope was represented in London only by an apostolic delegate to the country’s Catholic hierarchy rather than any representative to the Crown and its Government.)

Within a year of the Special Mission to Rome being established, John Duncan Gregory (later appointed CB and CMG) was assigned to it. A diplomat since 1902 who had previously worked in Vienna and Bucharest, he was one of the central figures in the curious ‘Francs Affair’ of 1928, when two British diplomats were believed to have unduly abused their positions to speculate in currency. Despite being cleared of illegality, J.D. Gregory was dismissed from his diplomatic posting — though he was later rehabilitated.

Within a year of the Special Mission to Rome being established, John Duncan Gregory (later appointed CB and CMG) was assigned to it. A diplomat since 1902 who had previously worked in Vienna and Bucharest, he was one of the central figures in the curious ‘Francs Affair’ of 1928, when two British diplomats were believed to have unduly abused their positions to speculate in currency. Despite being cleared of illegality, J.D. Gregory was dismissed from his diplomatic posting — though he was later rehabilitated.

If there are any enthusiasts of the curious subcategory of accoutrement known as the despatch box, J.D. Gregory’s one dating from his time in Rome is currently up for sale from the antiques dealer Gerald Mathias.

It was manufactured by John Peck & Son of Nelson Square, Blackfriars, Southwark — not very far at all from me as it happens. (more…)

175 Years of St George’s Cathedral

ONE HUNDRED AND SEVENTY-FIVE years ago, at a time of great uncertainty in Europe, St George’s in Southwark was opened solemnly by Bishop Wiseman — writes the Cathedral Archivist Melanie Bunch. The ceremony was attended by thirteen other bishops in all their finery, of whom four were foreign. Hundreds of clergy of all ranks were in the procession and many of the Catholic aristocracy of England were present. The music was magnificent, the choir including professional singers.

Pugin’s neo-Gothic church was impressive but not finished, and it was not to be a cathedral for another four years. Dr Wiseman, who was both the chief celebrant and the preacher, was bishop of a titular see, as the Catholic dioceses of England and Wales did not yet exist. Nonetheless the opening marked a significant stage in the revival of the Catholic Church in this region. The spur had been the spiritual needs of the poor Irish who had long formed settled communities in parts of London and other cities. The plans for the church had been drawn up in 1839 – before the severity of the famine in Ireland, which began in 1845, could have been foreseen. Some had considered the size of the new church unnecessary, but it turned out to be providential, as immigration from Ireland to this locality and elsewhere was reaching a peak at this time.

The extraordinary turmoil in Europe that had started early in the year in Sicily could not be ignored. In February Louis-Philippe was dethroned in France. There was anxiety that revolution might cross the Channel. Pugin decided that he should obtain muskets to defend his church of St Augustine under construction in Ramsgate. Revolution spread to German and Italian states and countries under Austrian rule. For four days in late June, there was a brief and bloody civil uprising in Paris.

While Europe was ablaze, London was calm, and the opening went ahead. In his homily, Wiseman praised God for all his mercies to this country. From our perspective, we might have expected that he would have spoken about the dark days of persecution, or at least the struggles of the recent past to get such a large church built, constantly hampered by lack of funds. Rev. Dr Thomas Doyle, whom we honour as the founder of the Cathedral, was present and assisting at the Mass, but his courage, faith, and dogged persistence over many years were not acknowledged on this occasion.

We might remember that a Catholic event like this had not been witnessed in England since the Reformation, seemingly prompting Wiseman to take the opportunity to explain to the non-Catholics present that the ceremony and display of the Catholic Church came from a desire to show greater respect for God. To the foreign bishops he said that their presence proved the unity and diversity of the Church. At the end of his homily, Wiseman caused a sensation by reading out a letter from the Archbishop of Paris, Mgr Affre, regretting that he could not attend the opening. By then it was known that he had already died from wounds received on the barricades while he was trying to mediate with the rebels. Wiseman called him a martyr.

Among others who never saw the opening are some who served St George’s mission with Thomas Doyle at the earlier chapel in London Road. Three of them had died before their time, only a few years before, from diseases endemic among their flock. We remember them and all who have served the Cathedral with gratitude. At the time of the opening, St George’s was the largest Catholic church in London, and for the next fifty years was to be the centre of Catholic life in the metropolis. Much has changed since, including the rebuilding of the Cathedral, but we give thanks to Almighty God who continues to sustain it. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories