2022 October

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Decline at The Villager

Though constantly mourning the never-ending decline in the quality of newspaper design, I hope everyone can agree that a vast depreciation has taken place at The Villager of Greenwich Village, New York.

Whereas the Village Voice was always the pretentiously showy alternative beat-turned-hippie-turned-bobo upstart of Village publications, The Villager has played the role of the actual neighbourhood sheet that gave you the local news.

Absurdly, the otherwise magisterial and much-loved Encyclopedia of New York City doesn’t even have an entry for The Villager — not even in its second edition! — despite the paper being founded back in 1933. (The Voice was 1955.)

Behold — witness the decline:

An issue from this past week in October 1959. The nameplate features distinct lettering, flanked by the supporters of a town crier (or perhaps we should say village crier) on one side and an image of the Washington Arch on the other.

No fewer than nine stories on the front page. (It’s a standard Cusackian rule of newspaper design that the more stories on the front page the better off you are.)

There is also a helpful reminder of the upcoming election so Village denizens can do their civic duty. (more…)

Puritan in Spanish Garb

Plymouth Congregational Church, Coconut Grove, Miami

The traveller passing down Devon Road in the Grove neighbourhood of Miami might be forgiven for thinking he had stumbled across one of the ancient mission churches that Spanish antecedents had established across the American realms of His Most Catholic Majesty the King of Spain.

The traveller would be mistaken, for what he has discovered is in fact the Plymouth Congregational Church.

It was completed in 1917 by one man Felix Rebom — to a design by architect Clinton MacKenzie. According to local lore, Rebom finished the building himself using just a T-square, a plumbline, a trowel, and a hatchet.

The congregation was founded in 1897 and four years later appointed as its pastor the Rev. Solomon G. Merrick — father of the developer George Merrick who built Coral Gables.

In one of the seemingly endless series of Florida property booms, the elder Merrick’s successor encouraged the congregation to buy a large parcel of land in Coconut Grove.

Dividing it into residential plots allowed them to raise the money to build the new church on the remaining part of the land.

The massive door — hand-carved walnut backed in oak — is in fact four centuries old and comes from a disused Pyrenean monastery.

Architecturally one of the few hints that this is delightful theatre rather than historic reality is that the style, while Spanish, is more Mexican than Floridian.

Florida’s lush climate also means half the building has been taken over by surrounding greenery. I love it.

Lafayette at the Seventh

For the first century or so in the history of the United States, there was no more popular Frenchman in America than the Marquis de Lafayette. This nobleman of the Auvergne was an officer in the King’s Musketeers aged 14 and was purchased a captaincy in the Dragoons as a wedding present aged 18 in 1775. Within a year the rebel faction in North America had sent Silas Deane of Groton to Paris as an agent to negotiate support from the French sovereign, but Paris acted cautiously at first.

Lafayette — a young aristocratic freemason and liberal with a head full of Enlightenment ideas — escaped to America in secret and was commissioned a major-general on George Washington’s staff in the last of his teenage years.

Given his relative youth, Lafayette inevitably turned out to be the final survivor of the generals of the Continental Army, and his 1824 trip to the United States solidified his popularity. He visited each of the twenty-four states in the Union at the time, including New York where the predecessor of the Seventh Regiment named itself the National Guards in honour of the Garde nationale Lafayette commanded in France.

This was the first instance of an American militia unit taking the name National Guard, which in 1903 was extended to all of state militia units which could be called upon for federal service.

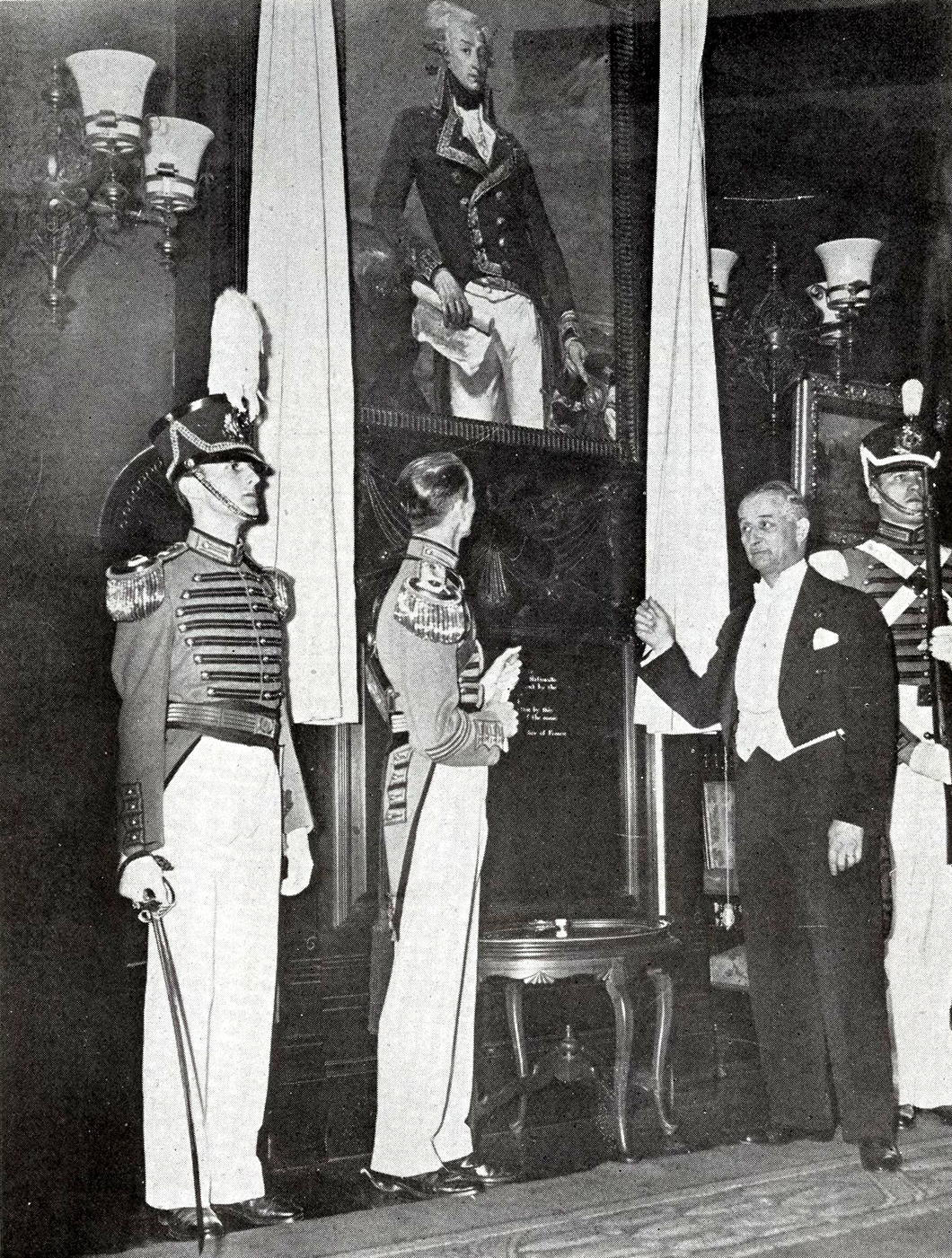

In honour of this connection and on the centenary of Lafayette’s 1834 death, the French Republic presented the Seventh Regiment with a copy of Joseph-Désiré Court’s portrait of the general that hangs in the 1792 Room of the Palace of Versailles. The Seventh set this in the wall of the Colonel’s Reception Room in their Armory, facing a copy of Peale’s portrait of General Washington.

The privilege of unveiling the portrait went to André Lefebvre de Laboulaye, the French Ambassador to the United States, who was given the honour of a full dress review of the Seventh Regiment on Friday 12 April 1935 before a crowd of three thousand in the Amory’s expansive massive drill hall.

Also present at the occasion was his son François, who eventually in 1977 stepped into his late father’s former role as French Ambassador to the United States. His Beirut-born grandson Stanislas served as French Ambassador to Russia 2006-2008 before being appointed to the Holy See until 2012. In April 2019, Stanislas de Laboulaye was put in charge of raising funds for the rebuilding of Notre-Dame following the fire that devastated the cathedral.

The Irishman at Yorktown

General Charles O’Hara and the Surrender of Lord Cornwallis

Today marks two-hundred-and-forty-one years since the British general Lord Cornwallis surrendered to a joint Rebel-French force at Yorktown in Virginia — perhaps the most embarrassing British defeat until the Fall of Singapore to the Japanese more than a century and a half later.

Every American schoolboy, or indeed any visitor to the United States Capitol, is familiar with John Trumbull’s oil painting of the scene at Yorktown.

Somewhat pitifully, Lord Cornwallis pled ill health and did not attend the formal ceremony of surrender.

Instead, he sent his adjutant to act on his behalf: a wily character by the name of General Charles O’Hara.

O’Hara had soldiering in his blood, being the illegitimate son of a Portuguese woman and Field Marshal the Rt Hon James O’Hara, 2nd Baron Tyrawley and 1st Baron Kilmaine. The elder O’Hara was the sometime envoy-extraordinary to the King of Portugal, where he made the acquaintance of the woman who bore him one of at least three of his sons-born-the-other-side-of-the-blanket.

Lord Tyrawley looked after his son, sending him to Westminster School before buying him an army commission and keeping him close by in the Coldstream Guards which the father commanded himself.

Young Charles was at one point sent on assignment to Senegal commanding a corps of African army convicts which, reading between the lines, may have been a punishing demotion.

He soon regained his command with the Guards though and was sent to America where the royal troops were fighting against a surprisingly cohesive force of rebel English colonists.

Despite being surrounded by numerous American loyalists, O’Hara tended to distrust the colonists and viewed them with suspicion, tarring them all with the brush of rebellion openly practiced only by a distinct (but ultimately successful) minority.

He was wounded at the Battle of Guildford Court House in March 1781, and by the Siege of Yorktown had been promoted to Cornwallis’s second-in-command. (more…)

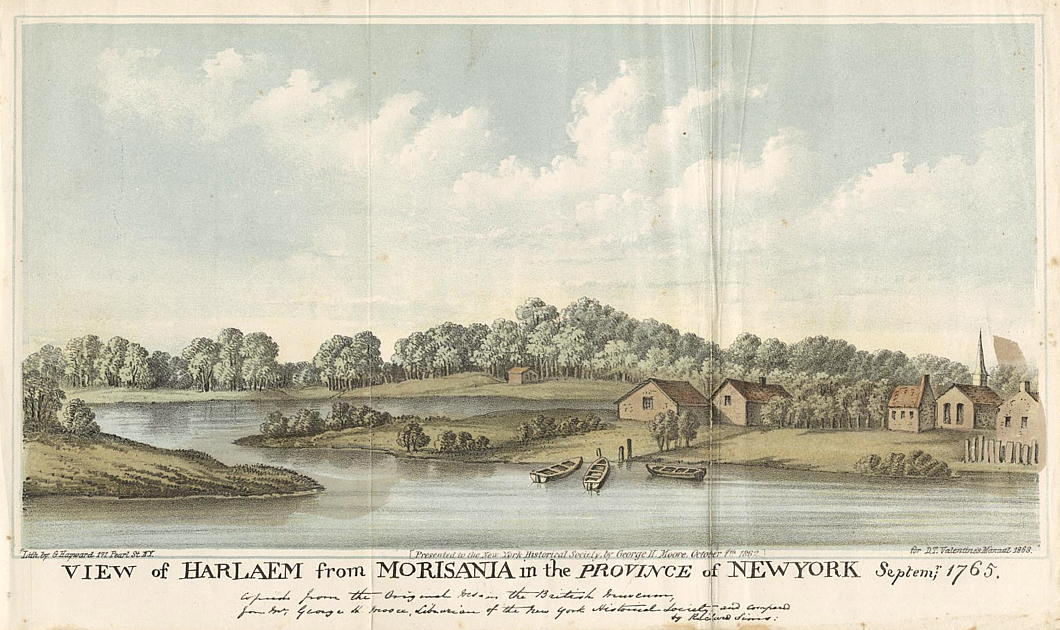

Harlem Reformed Dutch Church

For much of Manhattan’s early colonial history, the island was home to two primary settlements: the port of New Amsterdam (later, from 1664, New York) way down at the southern tip and the town of Harlem up where the East River meets the Harlem River.

Christened after the Dutch city, Harlem is one of Manhattan’s most visible links to the Netherlands. The local newspaper is even called the New York Amsterdam News, once a prominent voice in Black America given this neighbourhood became predominantly African-American in the early twentieth century, and Amsterdam Avenue runs up as the spine of West Harlem.

Harlem was founded in 1658, thirty-four years after New Amsterdam was founded and thirty-two since Peter Minuit bought the whole island of Mannahatta off the Indians for sixty guilders.

The town’s first church was founded in 1660 but didn’t have its own dedicated building for a few years. The Harlem Reformed Dutch Church, or Collegiate Church of Harlem, was built in 1665-67 right on the banks of the Harlem River, around the site of East 127th Street and First Avenue today.

Both the building and site was abandoned twenty years later when the congregation moved to its second building, completed 1687, just a little bit further south — near where East 125th meets First Avenue, or where the entrance ramp to the Triborough Bridge meets 125th.

It is this second building, which is depicted in the view above of Harlem village from Morissania across the river in the Bronx in 1765 (below).

Mistranslating Apostates

ONE OF THE historical anecdotes I enjoyed being taught at school was the death of the Emperor Julian the Apostate — as relayed by our much-esteemed teacher Dr Nathaniel Kernell. This was in the Christian era with the capital at Constantinople rather than the Eternal City itself — Julian had (as betokened by his moniker) abandoned Christianity aged 20 and sought to frustrate its spread.

He wanted to promote the old Greek gods, dabbled in vegetarianism, and even tried to rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem. Mysterious fires consumed the workers tasked with that final project and it is presumed many Jews didn’t want to be dragged into the Emperor’s political project the animus of which was opposition to Christianity rather than promotion of Judaism.

Anyhow, none of Julian’s projects came to much fruition and as he lay dying from an injury in battle, the apostate emperor realised the futility of his life’s work with his final words: νενίκηκάς με, Γαλιλαῖε, or ‘Thou hast defeated me, Galilean!’

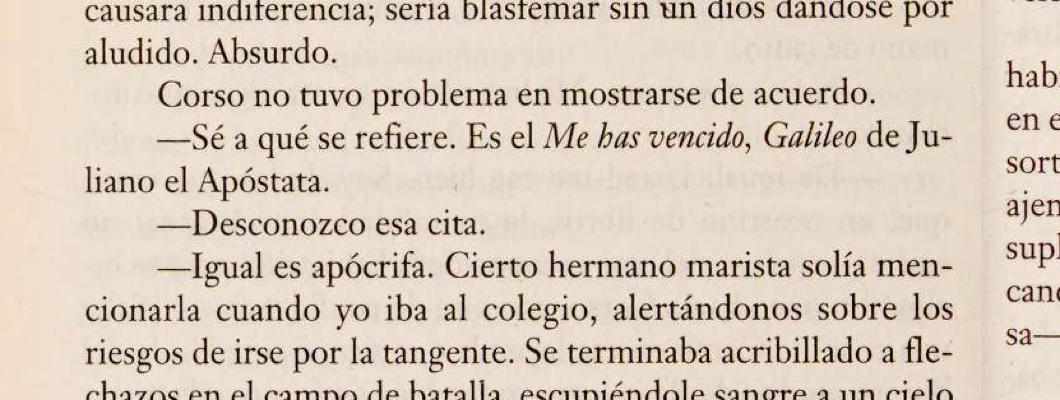

At the moment I am reading a book by Arturo Pérez-Reverte and stumbled across a mistranslation from the Spanish that would have been avoided if only the translator had enjoyed the privilege of being taught by Dr Kernell.

It turns out that the Spanish word for ‘Galilean’ is ‘Galileo’. Pérez-Reverte’s translator, alas, failed to understand one of the characters reference to Julian’s final words and mistook Christ our Saviour for an Italian astronomer, mistranslating the phrase as “You have defeated me, Galileo”.

Worth a wry smile, given the solid 1,200-year gap between the death of Julian the Apostate and the birth of Galileo Galilei.

The Dumas Club is a delightfully weird and intriguing tale, though, and I look forward to reading more by Pérez-Reverte — no matter who the translator is.

The Sultan Nazrin Shah Centre

Níall McLaughlin Architects at Worcester College, Oxford

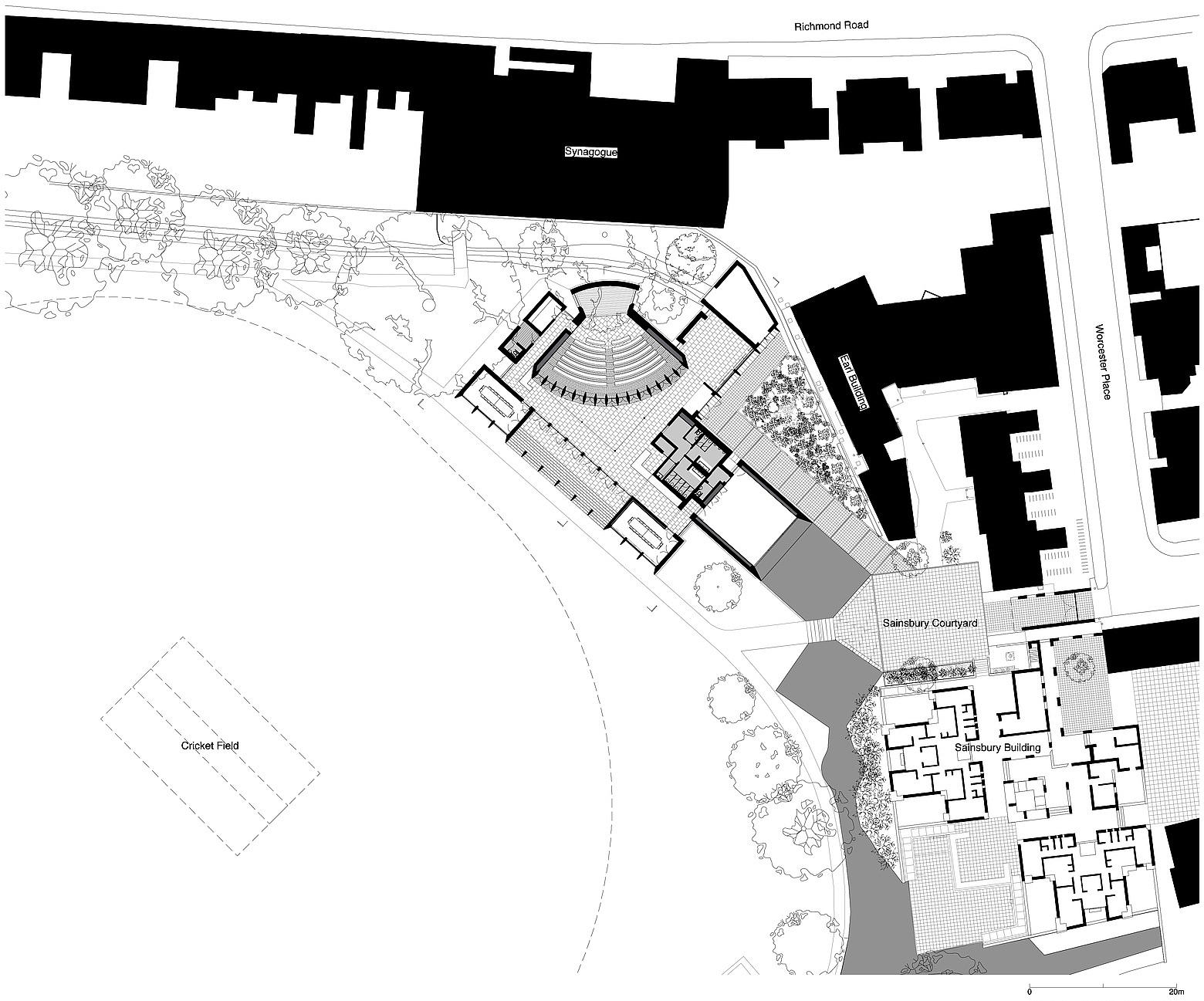

WORCESTER is one of the most spacious and scenic of Oxford’s colleges. The classical symmetry of its entrance terminates the view down the gentle curve of Beaumont Street from the Ashmolean Museum. The twenty-six acres of its grounds are pastoral, with lake, gardens, and the broad expanse of a cricket pitch.

Craftily inserted into this arcadia is the Sultan Nazrin Shah Centre designed by Níall McLaughlin Architects. Collegiate work is familiar to this firm, whose new library at Magdalene College, Cambridge, has won them this year’s Stirling Prize, and the Shah Centre provides new useful facilities for the college without giving it the middle finger.

It is named in gratitude to the generosity of an old boy of the college, HRH Nazrin Ali Shah of Perak, who delights in the title of Sultan, Sovereign Ruler, and Head of the Government of Perak, the Abode of Grace, and its dependencies. Judging by the outcome — itself shortlisted for a Stirling Prize in 2018 — I think he spent his money well.

Tempting though it might be to have a gentle wander through the grounds of the college first, the Shah Centre is best approached through the humble entrance lodge nestled in the corner of the L-shaped Worcester Place north of the college.

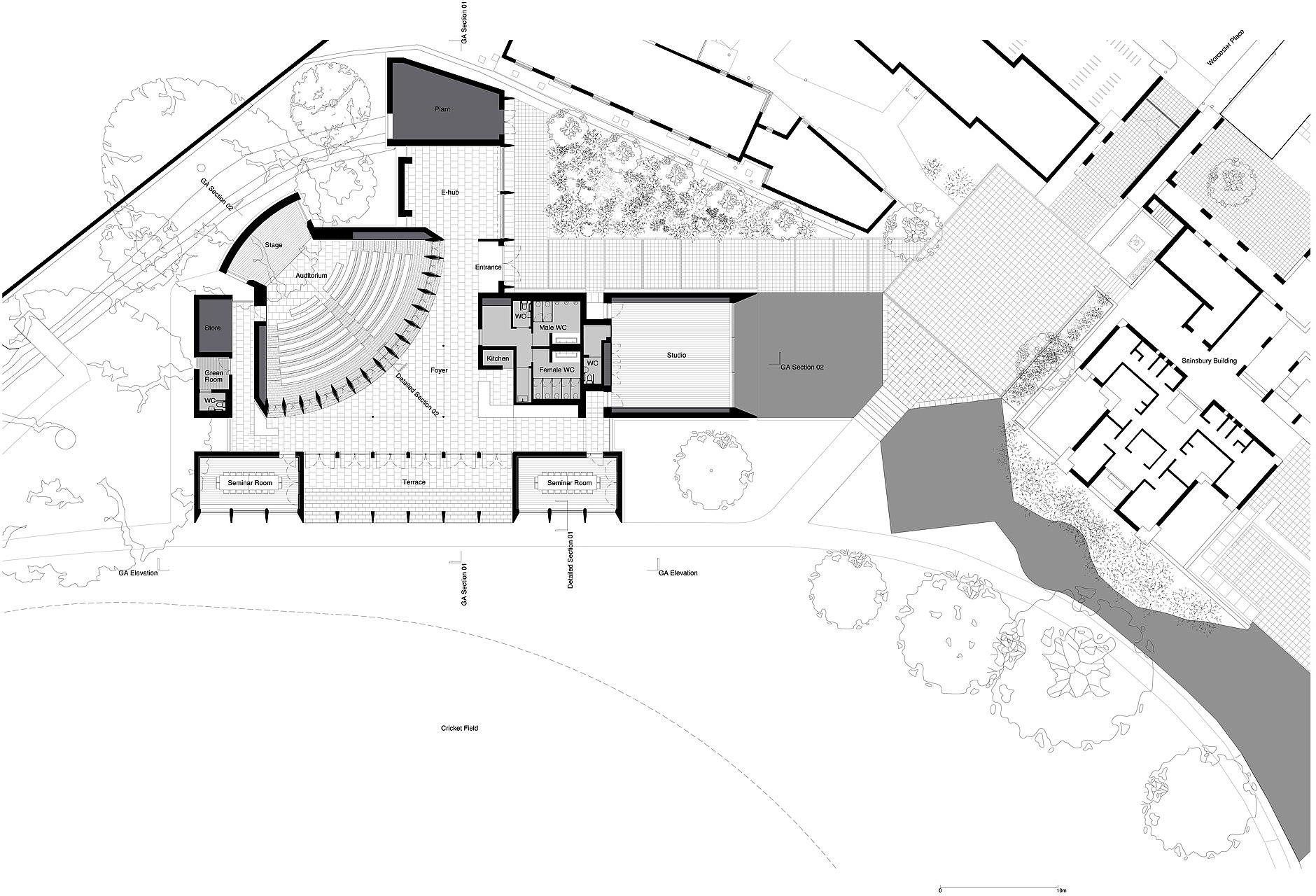

You are led to a little piazza — the Sainsbury Courtyard — framed by a pair of just-below-foot-level diamond-shaped shallow ponds of Kahn-ian geometry. (They are actually a tiny extension of the college lake.) The broad expanse of cricket pitch beyond, connected by a flat wooden bridge segmenting the two diamond ponds, is alluring. But off at a 45-degree-angle on the right, the entrance to the Shah Centre bids the visitor on.

Beyond the limestone cladding you move indoors to a sea of light-treated oak, in the thin supporting columns of the one-storey entrance hall curving around the arc of the lecture theatre and in the trelliswork ceiling.

To the left, the dance studio looks out onto the pools through three giant panes of floor-to-ceiling glass.

To the right, a small bar can double as a registration desk.

The lecture theatre seats 170 and is accessed through a curve of wooden slats that hide panels that can swing out if closing the space is necessary.

Auditoria with ceilings sloping down toward the stage usually feel cramped but here the ceiling is arranged in sharp corrugations (like the flanges of the Gonbad-e Qabus) which capture the light from the clerestory behind.

The feeling is one of spaciousness: rather than facing downwards they are like rays of the sun reaching outwards and up. Instead of wings offstage, there are tall windows of a single sheet of glass flanking, offering natural side light.

The view from the stage is even better, looking out at the gentle curve of clear windows breaking at near-half-way, dividing the anterior spaces below from the open skies above.

Straight out from the auditorium is the terrace with its steps flowing gently down to the field beyond.

It is from the cricket ground that we get the best view of the Shah Centre. The lines are elegant, and there’s a hint of the better architects from Italy’s fascist era — Pagano or Terragni, not Piacentini. The easy movement of space and light, with a gentle breeze rolling off the green.

The architectural genius of the Oxford college as a type is that it allows for the magnificent to be completed on a humane scale for an intimate community of students, scholars, and academics. Níall McLoughlin’s skill at achieving this in a modern idiom is what makes the accolades he accrues — fickle gifts at the best of times — so justified in his case.

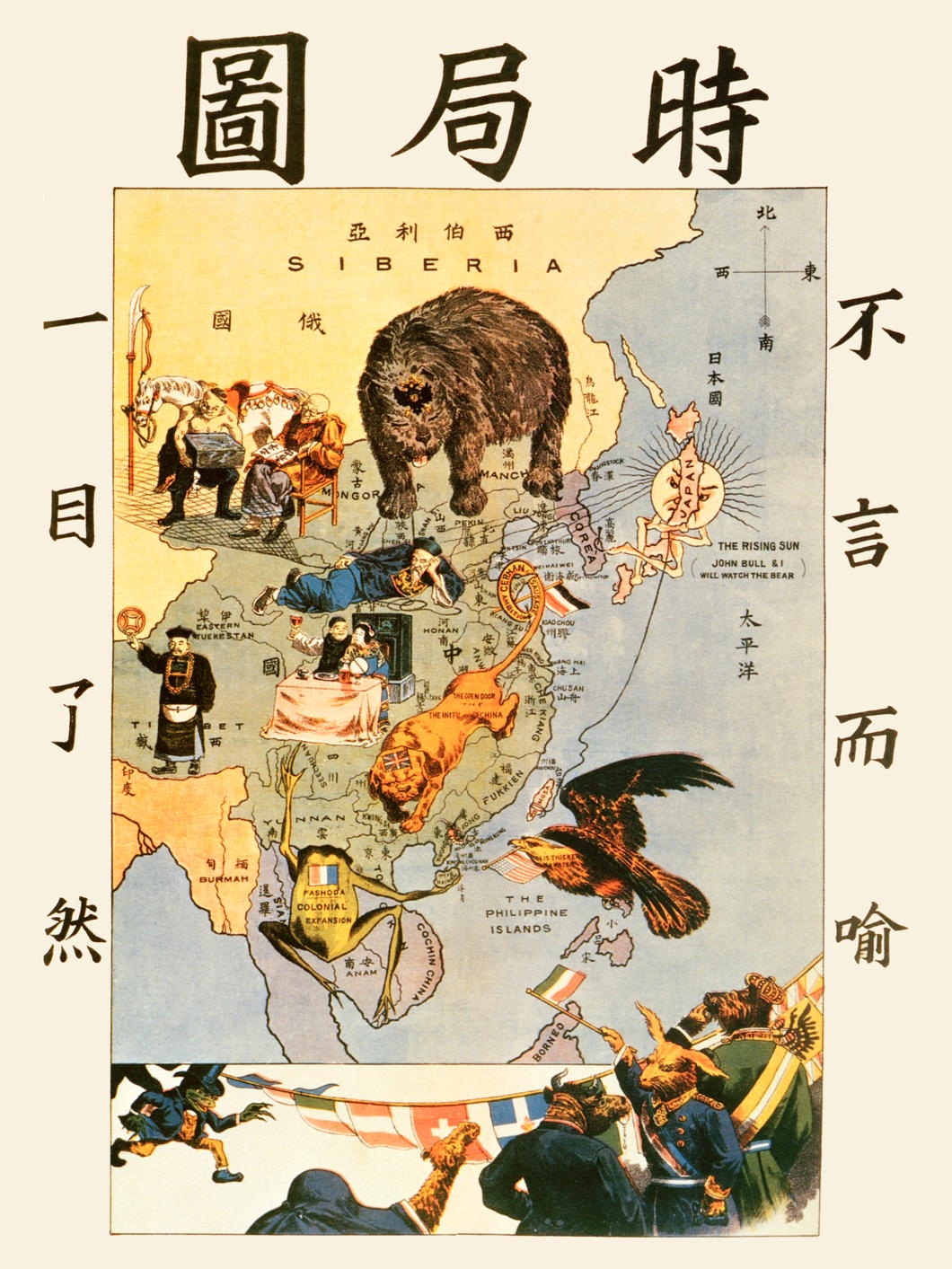

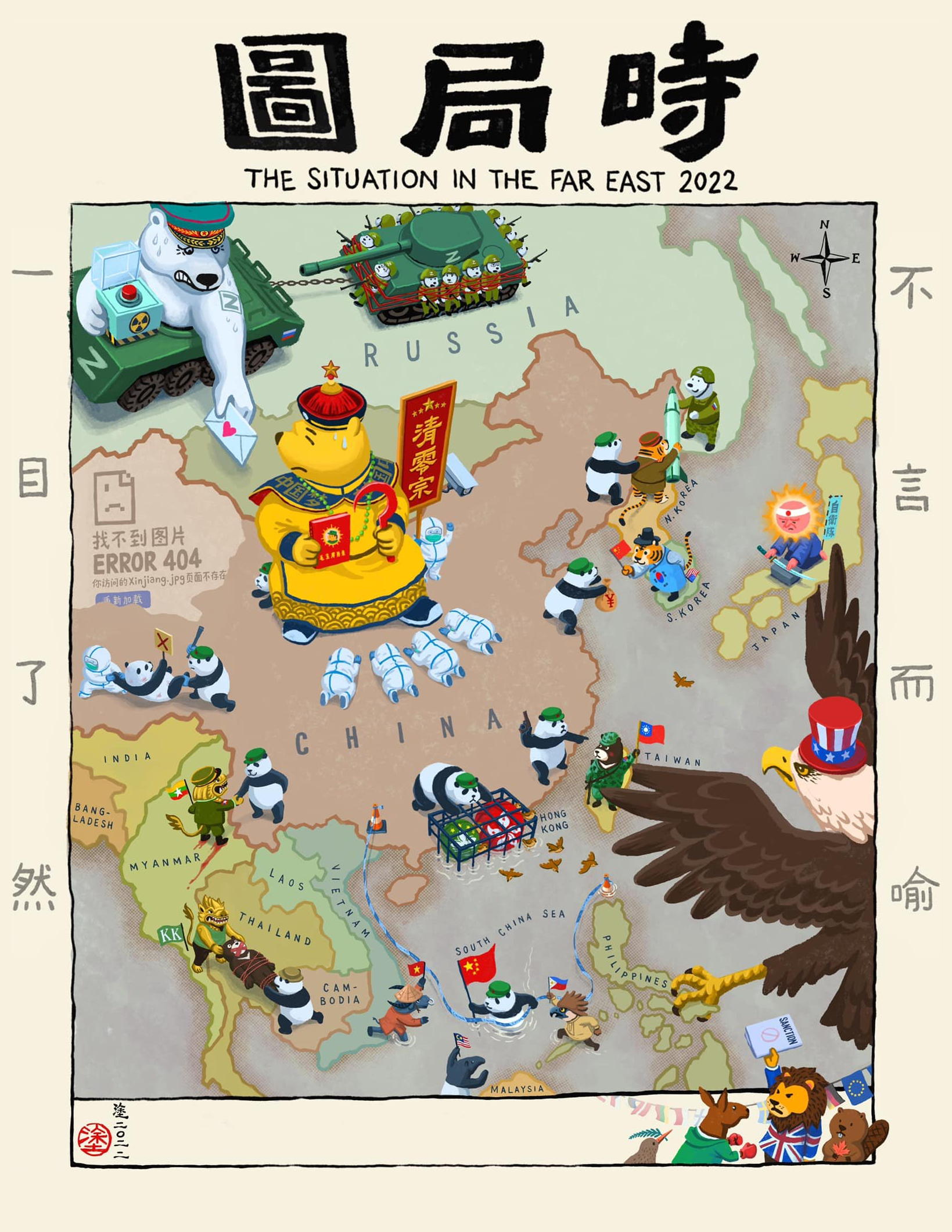

The Situation in the Far East

A century-old geopolitical cartoon is updated for today

Tse Tsan-tai — or 謝纘泰 if you fancy — was by any standard a remarkable man. Born in New South Wales, this Chinese-Australian Christian was a colonial bureaucrat, nationalist revolutionary, constitutional monarchist, pioneer of airship theory, and co-founded the South China Morning Post — still one of the most prominent newspapers in the Orient.

Tse’s most important visual contribution was a widely distributed political cartoon usually known in English as ‘The Situation in the Far East’ or in Chinese as the ‘Picture of Current Times’ (below).

Crafted as a propaganda measure to warn his fellow Chinese of the designs of foreign powers, the cartoon depicts the perils facing the Middle Kingdom.

Japan, with its expanding navy, proclaims it will watch the seas with its ally, Great Britain. The Russian bear looms from Siberia, crossing the border into China. A British lion sprawls over the land, its tail tied up by the “German Sausage Ambitions” at Tsingtao. The French frog guards Indochina while the American eagle lurks from the Philippines.

Meanwhile, the Chinese figures show sleeping bureaucrats and carousing intelligentsia unresponsive to the external threats.

Now the exiled Hong Kong artist Ah To (阿塗) has updated ‘Situation’ to reflect the realities of 2022. (more…)

The death of The Monarch

The revered Sovereign’s death was announced in the evening. The daily anxieties of the people and the press’s usual reporting on quotidian political strife temporarily evaporated on contact with the momentous royal bereavement. Though long anticipated, the loss was profound, raw.

To many it felt like a moment of overdue reckoning. As if the frail body of the elderly monarch had somehow been holding the great, ancient, long-weakening and precariously multinational state together. The world of the previous century had finally, almost imperceptibly, slipped away. Franz Joseph was dead. …

In the October 2022 number of The Critic, Dr John Ritzema explores the parallels between the recent demise of our late sovereign with the death of the Emperor Franz Joseph over a hundred years earlier — and wonders whether there are any lessons for the reign of King Charles III: Rebuilding a Monarchy and a Nation.

One of those minor curiosities that both Franz Joseph and Elizabeth II were succeeded by Charleses — the latter by her son, and the former by his grand-nephew Blessed Charles of Austria.

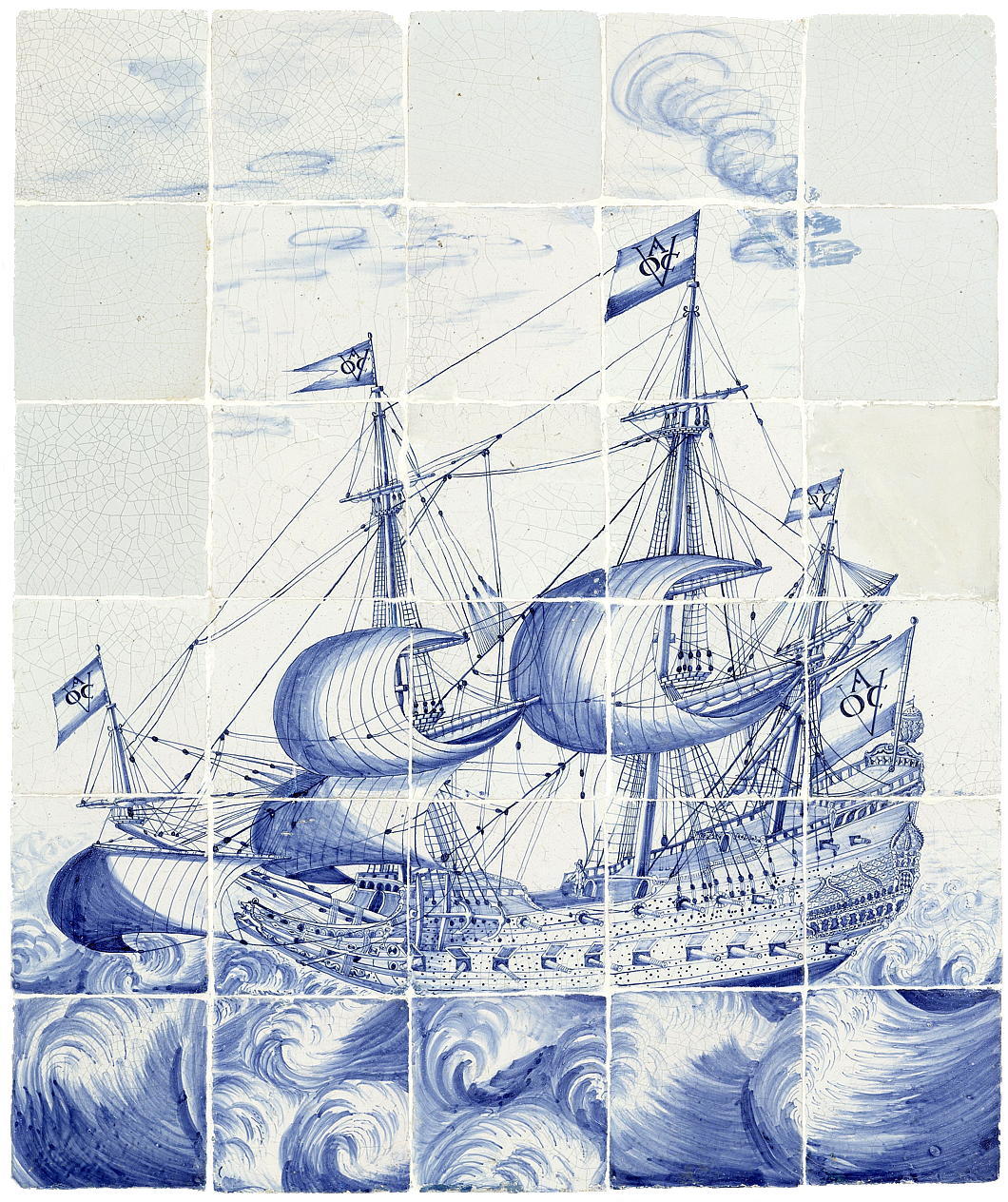

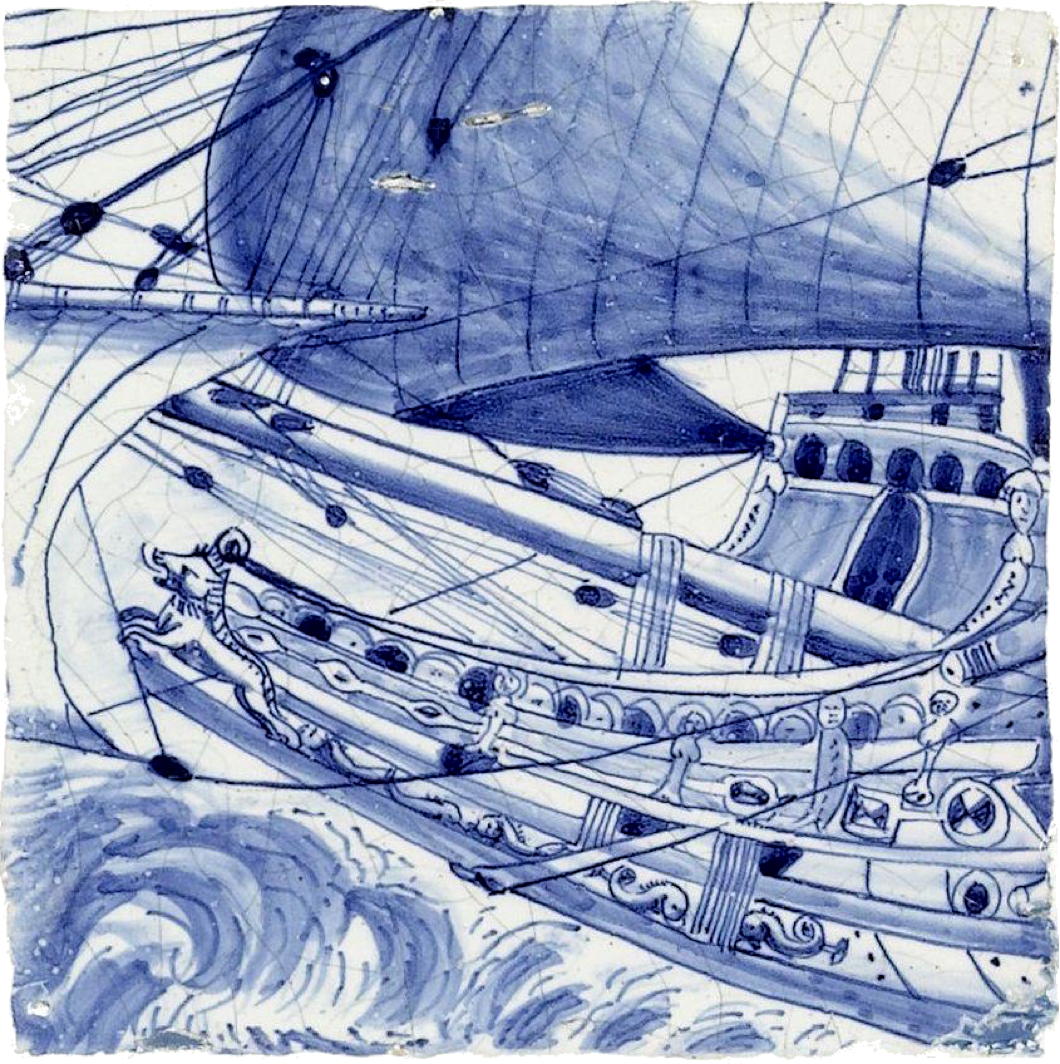

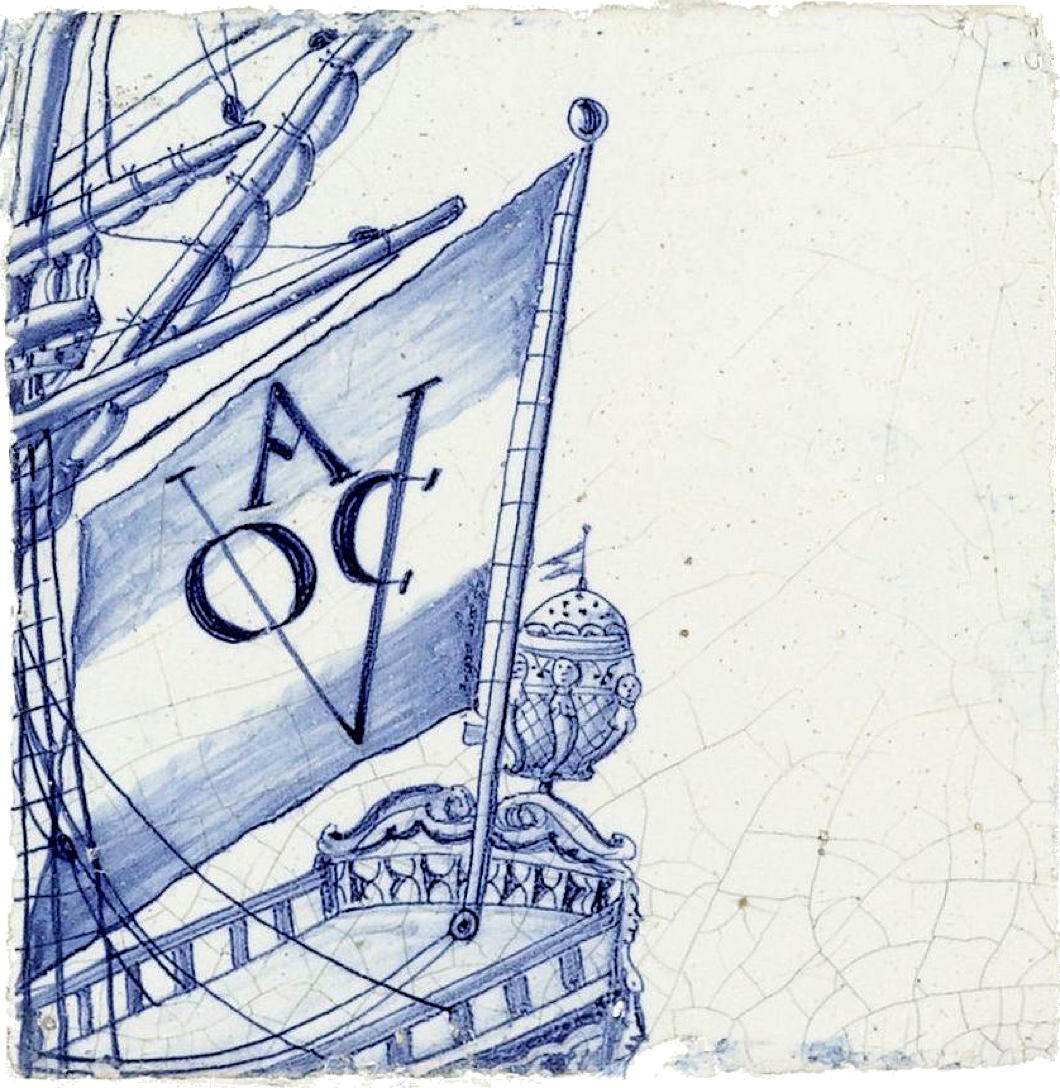

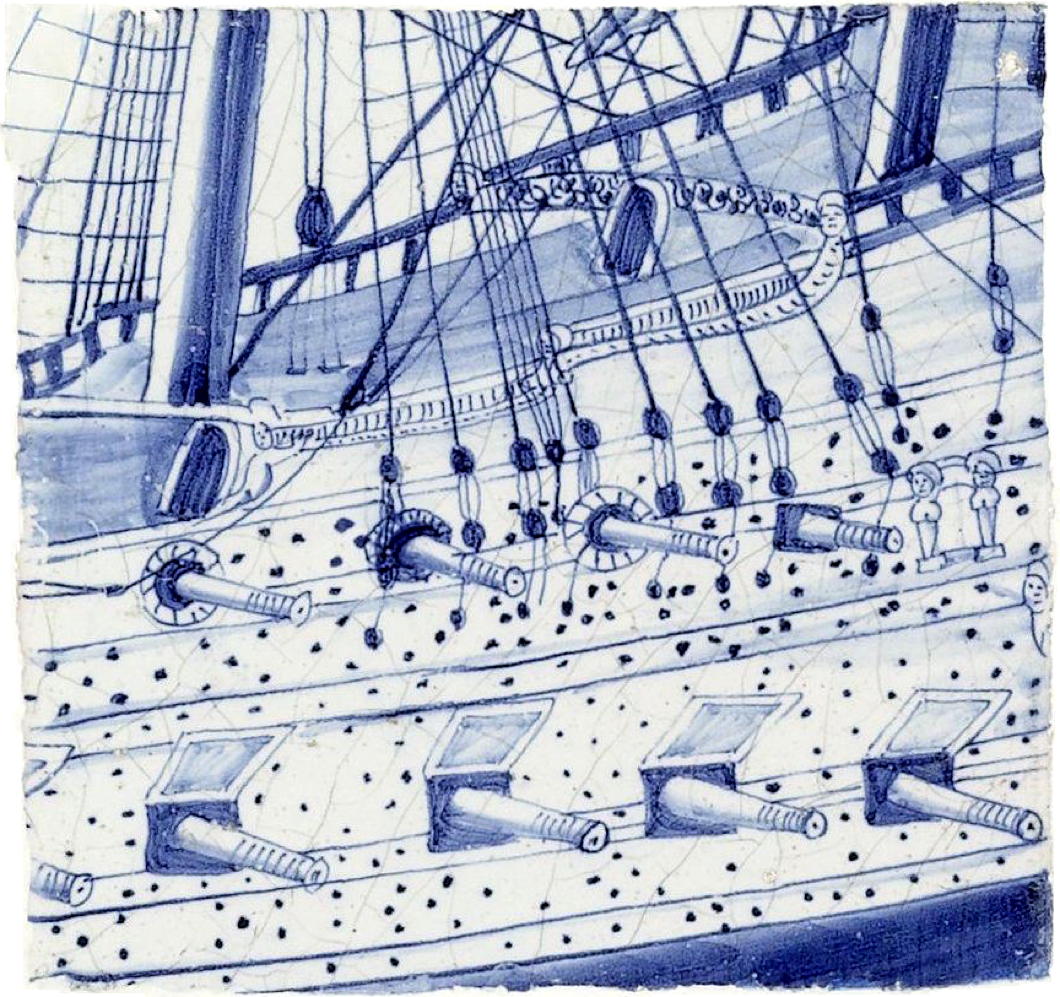

An East Indiaman

English sea-goers and merchants commonly referred to any ship of the Dutch VOC (or of other similar companies) as an ‘East Indiaman’.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories