About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

‘Solving’ Middle Europe

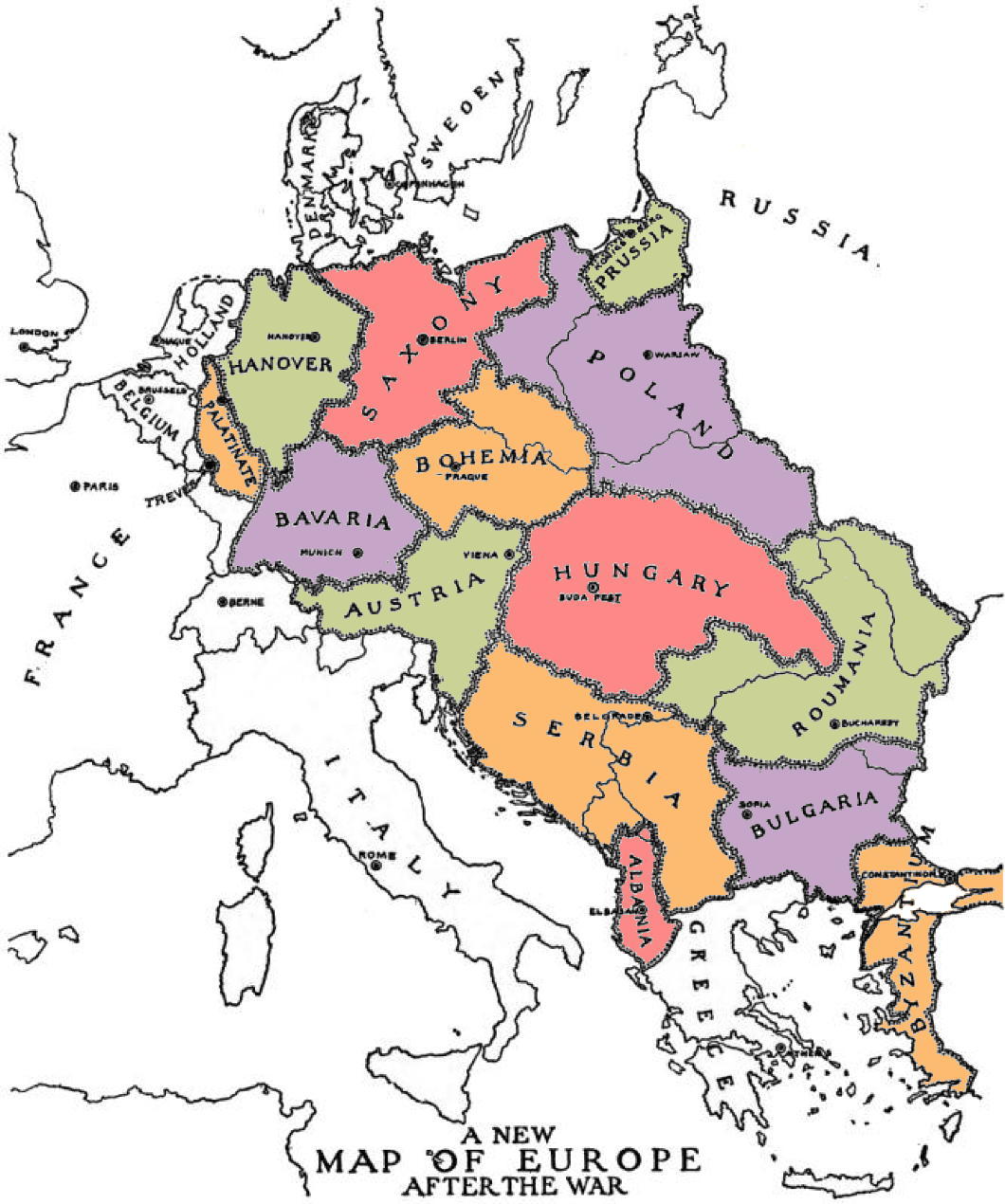

Ralph Adams Cram’s First-World-War Plan for Redrawing Borders

Ralph Adams Cram was not just one of the most influential American architects of the first half of the twentieth century: he was a rounded intellectual who expressed his thinking in fiction, essays, and books in addition to the buildings he designed.

Cram (and arguably even more his business partner Goodhue) had a gift for bringing the medieval to life in a way that was neither archaic nor anachronistic but instead conveyed the gothic (and other styles) as living, organic traditions into which it was perfectly legitimate for moderns to dwell, dabble, and imbibe.

His literary efforts include strange works of fiction admired by Lovecraft and political writings inviting America to become a monarchy. These have value, but it’s entirely justifiable that Cram is best known for his architectural contributions.

All the same, amidst the clamours of the First World War this architect of buildings played the architect of peoples and sketched out his idea of what Europe after the war — presuming the defeat of the Central Powers — would look like.

In A Plan for the Settlement of Middle Europe: Partition Without Annexation, Cram set out his model for the territorial redivision of central and eastern Europe “to anticipate an ending consonant with righteousness, and to consider what must be done… forever to prevent this sort of thing happening again”.

Cram, who provided a map as a general guide, predicted the return of Alsace-Lorraine to France, Schleswig-Holstein to Denmark, the Trentino and Trieste to Italy, much of Transylvania to Romania, Posen to a restored Poland, and Silesia divided in three.

Fundamental to the architect’s thinking was that “neither Germany, Austria-Hungary, nor Turkey can be permitted to exist as integral or even potential empires”. Austria and Hungary would be split and Germany needed to be partitioned (not, as some later plans had it, annexed).

In the south, Bavaria, Württemberg, and Baden would form a new Catholic state. Saxony would include Brandenburg, Mecklenburg, and Pomerania. A restored Palatinate sits in the Rhineland while as much of Schleswig-Holstein as will protect the Kiel Canal is given to Denmark. Hanover takes the rest of what we now know as Germany.

Prussia — the big bad boy of Germany — is reduced to a cut-off rump “under the sovereignty of the House of Hohenzollern — if the tastes of the people incline in that direction”, though Cram considered combining Prussia with Livonia and Courland as punishment.

Noble Poland, meanwhile, “is given the frontiers of about 1560, and is made a sovereign and independent kingdom”.

Yugoslavia is made a reality under the Serb monarchy, as indeed did happen, but Cram suggests that Carinthia, Carniola, and Slovenia continue in union with Austria.

Further east, things get more interesting. It’s not merely Germany and Austria-Hungary that, according to Cram, need to be split up, but also the Ottoman empire. Cram imagines a new, multi-racial Byzantine buffer state existing around what once was the New Rome:

Constantinople, with the Thracian remains of “Turkey in Europe” together with the lands along the Sea of Marmora and the Ægean, becomes a new Byzantium, independent but bound to keep forever open the Bosporus and Dardanelles.

It must be admitted it will be a polyglot and a more or less artificial state, Greek, Levantine, Turkish; but Constantinople can no longer remain Turkish, it can become neither Greek nor Russian nor Bulgarian, and its constitution as a “free city” under international guarantees, is as impracticable as it would be insecure.

As civilization begins again after the war it is bound to work its way eastward into Asia Minor, redeeming an impoverished but once fertile land. How far, in anticipation of this inevitable event, it may be possible to go at present is a question, but enough of the coast line should be taken to link up with Smyrna, and of a sufficient depth to be strategically tenable.

Cram also had bigger ideas for the future organisation of Europe. He recognised the utility of a future concert of nations exercising some significant authority over its member states. But he decried the idea of a United States of Europe as “a fond thing vainly imagined”.

“Each and every state,” he imagined, “should maintain its independence and autonomy, with full power to determine its own system of government, carry on its own legislation, manage its internal and external affairs, with no sacrifice of sovereignty.”

All the same, there must be some “definite centre of visible and potent European authority, with power to deal with all international questions, but with no local authority whatever”.

Cram proposed this authority be based in a separate city-state of “Treves” — better known to us as Trier today — “a city of enormous antiquity, marked by the tradition of supreme secular power under the Roman emperors, and well guarded by its surrounding states”.

This “Federal City” would be inviolable and under the joint guarantee of all the nations of Europe. Here would be permanently assembled a Congress of Ambassadors representing all the States in Europe, under the presidency of a Supreme Executive chosen by the Congress and holding office for life.

Cram did not imagine his plan was a cure-all and he provided the map more as a general guide of his thinking instead of a precise solution. He was under no illusions that there was numerous cases that would take great difficulties to “solve”.

“Silesia, Galicia, Transylvania, Slavonia, Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria,” after all, “offer intricate problems of race, language, religion, social predilections, that can be determined only after conscientious and disinterested study, and honest consultation with the several peoples involved.”

But in place of two great empires, Cram’s plan for Europe imagined “ten free, autonomous, and completely independent units; homogenous, individual in character, and constituted in accordance with the human scale”.

[I]t gives each group full liberty of self-development, while it should, and in many cases undoubtedly would, mean a stronger sense of local pride, national self-consciousness and personal liberty.

Hungary, Saxony, Bohemia, were political and social entities of greater honour, vigour and prestige while they were severally independent, even though small in territory, than they have been since their merging in great Empires where their identity was lost.

These new/old states with their new/old borders “would be susceptible of a more normal, sane and wholesome development than was possible under the conditions that existed before the war.” Each is endowed with a history “full of vigour, heroism, exalted character” according to Cram.

“Let the several states now reassume their own independence, reassert their inherent individuality, and, taking up their history where it was cut off by imperial madness, go on to redeem themselves from the stigma burned into them by a Prussian war, and to build new history on the old and honourable lines.”

Many of Cram’s ideas and suggestions when it comes to “the settlement of Middle Europe” were eminently sensible. On the whole, had this plan been put into action it would have saved us a great deal of bother, to put it lightly, and certainly millions of lives lost in the second war.

Scale was fundamental, and he considered both Germany and Austria-Hungary too big for their own good — too big certainly for their inhabitants.

The essence of the Christian civilization of the Middle Ages was its human scale. It was a great unity built up of groups organized on the basis of human association. Decentralization was its strength and its virtue. Men lived and worked in manageable human units — feudal estates, parishes, guilds, communes, free cities, monasteries, orders of knighthood, colleges, principalities, small kingdoms. With the Renaissance came in the idea of nationalism, which bloated into imperialism; and during the nineteenth century this imperialism be came an insanity and an incubus.

For seventy years the imperialism of the world has invaded and destroyed individual rights, abolished wholesome human associations, substituted phrases and symbols for the coordinating and stimulating force of fellowship, and become in the end nothing more than the concentrating of power, and the employment of power, for the capturing and localizing of trade, the creation of markets, and the exploiting both of proletarian labour and the savage or “backward” races and communities of the globe.

How much of that medieval ideal was (or, rather, is) recoverable is a matter of debate to this day, but Cram’s outline is at least an interesting starting point.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Gellner’s Prague December 19, 2024

- Monsieur Bayrou December 18, 2024

- Dempsey Heiner, Art Critic December 17, 2024

- Vote AR December 16, 2024

- Articles of Note: 12 December 2024 December 12, 2024

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

All kingdoms I presume?

Hanover for the Duke of York that was? And Saxony’s Catholic monarchs to rule over overwhelmingly Protestant subjects? Why not – they had done so for centuries in Saxony itself after all. And Bavaria should always be a kingdom with at least a simulacrum of a Ludwig II at the helm.

But I am quite sure that Prussia, Hohenzollern led or not, would have won it all back in short order. The Junkers are not to be put down.

By the way, and speaking of the Hohenzollerns, if, as some rumours have it, Putin is planning to restore the Czars, then the most prominent candidate would be Grand Duke George, son of Grand Duchess Maria Vladimirovna. What many people forget is that his father is Prince Franz Wilhelm of Prussia, not only a Hohenzollern, but a great grandson of Kaiser Bill.

Putin has already decided to exchange the presidency for the prime ministership, which will then be the position of real power. A constitutional monarch rather than a pallid president would be the, ahem, crowning touch to his ambitious plans to make Holy Russia great once again.

All kingdoms.

Regarding Russia, I won’t hold my breath to wait for Putin’s move, welcome though it would be.

And it would rile all the right people.

Not entirely relevant but I stumbled across Golo Mann speaking at Chatham House in 1961:

“It is [Karl] Jaspers, too, who has the courage to say aloud what many of his fellow-citizens nowadays think but do not wish to say: that the German demand for reunification as a sacred right is based on an illusion; that it is based on the mistaken assumption that the national state founded by Bismarck, crippled through the First World War and then wantonly risked again and destroyed, nevertheless still exists. It exists no more, Jaspers holds, and the Federal Republic is something new and therefore definite, not the mere locum tenens of a theoretically exiting ‘Reich’.”

But, Golo adds, “Personally I am not quite as certain about this as Jaspers is.”

Where to begin?

Although I treasure a copy of his book on church symbolism, and love his work, his plan is the kind of insane liberal tinkering that always leaves us worse off. Leave Austria without Trieste? Give Poles access to the sea? Both were done, and guaranteed both Anschluss and the Invasion of Poland. Better to have left the map as near as possible as it was, and just grant Poland a trade concession to ship goods through Germany to a port complex built by themselves. Breaking up Austria-Hungary and cutting it off from the sea made it easy pickings for Germany. The whole scheme is based on an uncritical acceptance of German war guilt that cannot be supported by fact, and relies on British propaganda.

Too right! Trieste (and Istria) should have gone to Austria.

But, then again, this is mere quibbling over a plan that never really was.

As for German war guilt, I know a chap here in London who insists on referring to the first war as the “War of Belgian Aggression”.