2020 December

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

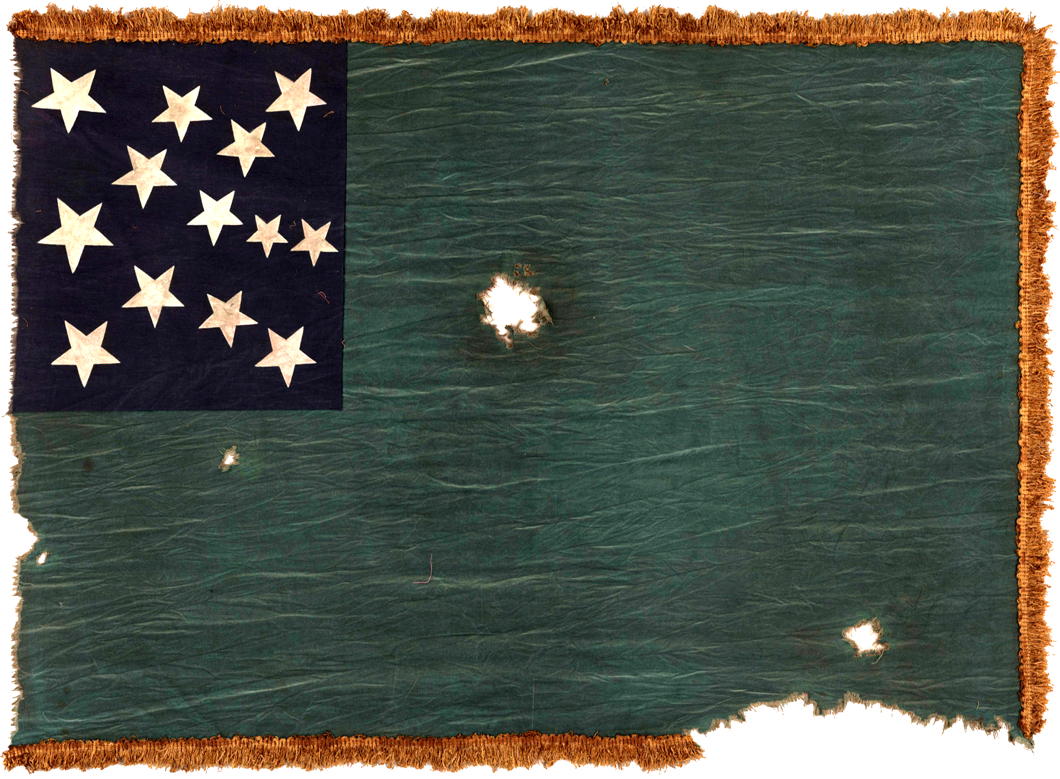

The Green Mountain Flag

One of my favourite American flags is the war flag of the State of Vermont, better known as the banner of the Green Mountain Boys. The Boys were a ragtag militia founded in 1770 to prevent the encroachments by the Province of New York upon what was then known as the New Hampshire Grants — land west of the Connecticut River that was claimed by both New York and New Hampshire.

The dispute between the two was eventually settled in favour of a third party: the state of Vermont which declared its independence in 1777 (as the Republic of New Connecticut) and in 1791 was the first state to be admitted to the Union that was not one of the original thirteen colonies.

During the Revolution, the Green Mountain Boys fought under Ethan Allen and at the Battle of Bennington they marched under a green flag with a blue canton bedecked with thirteen stars. The canton of this original flag still survives at the Bennington Museum.

While Vermont’s state flag has undergone a variety of transformations, the state has preserved the Green Mountain Flag as its war flag, used by both the Army and Air components of the Vermont National Guard and the Vermont State Guard.

The flag is also popular amongst supporters of Vermont’s reclaiming its independence, an issue explored by Vermont Public Radio as well as in a book by Bill McKibben and a collection of essays.

The Galloway Cross

What could be better than a hoard — and a Kircudbrightshire hoard at that? Sometime during the tenth century, a gentleman decided to deposit an interesting array of objects in Galloway only for them to be rediscovered by a metal detectorist in 2014.

Thus have come to us the Galloway Hoard, a collection of objects the most important of which is this pectoral cross made of silver and decorated with symbols of the four evangelists: the eagle of John, the ox of Luke, the angel of Matthew, and the lion of Mark.

As the hoard was buried when Kircudbrightshire was part of Northumbria — before the area became Scottish — the art has been identified as Anglo-Saxon from the age of the Vikings. My theory is an expert thief was at work, nicking precious objects from hapless victims — an armband gives the name of one poor Egbert in runes.

“The pectoral cross, with its subtle decoration of evangelist symbols and foliage, glittering gold and black inlays, and its delicately coiled chain, is an outstanding example of the Anglo-Saxon goldsmith’s art,” Dr Leslie Webster, an expert, said. “It was made in Northumbria in the later ninth century for a high-ranking cleric, as the distinctive form of the cross suggests.”

The Galloway Cross, before cleaning and conservation

All treasure found in Scotland must be reported to the Queen’s and Lord Treasurer’s Remembrancer who in 2017 determined the hoard’s value at £1.8 million. Scots law allows the discoverer to keep the full value of the hoard if there is no owner, though as it was found on glebelands belonging to the Church of Scotland that body’s General Trustees demanded a cut as well.

The objects themselves have found a home in the National Museum of Scotland who will be exhibiting them from February until May when they will go on tour to Aberdeen and Dundee.

Septuagesimo Uno

Septuagesimo Uno is often believed to be the smallest park under the purview of the Parks Department of the City of New York. It’s not. (By my reckoning, the Abe Lebewohl Triangle where Stuyvesant Street meets 10th Street near St-Mark’s-in-the-Bowery is the smallest.)

Though not the smallest, this park on West 71st Street is charming all the same. The site was acquired in 1969 thanks to Mayor Lindsay (or “Lindsley” as my maternal great-grandfather always mispronounced his name) and his Vest Pocket Park initiative. The small building on the lot was condemned and demolished by the City though it was only handed over to the Parks Department in 1981.

Originally known as the “71st Street Plot”, Parks Commissioner Henry Stern thought the name was too boring so rechristened it under the Latin moniker Septuagesimo Uno — Latin for ‘seventy-one’. (more…)

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories