2020 October

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

Arms and the Man

GOVERNOR CUOMO — is there anything that man won’t fiddle with? Is there nothing that can escape his grasping hands? Are we to suffer from the incessant interference of this megalomaniac forever?

The latest trespass His Excellency has committed is to encroach upon the very sacred symbols of the Empire State itself: our beloved coat of arms — and, by extension, the flag which also bears it aloft.

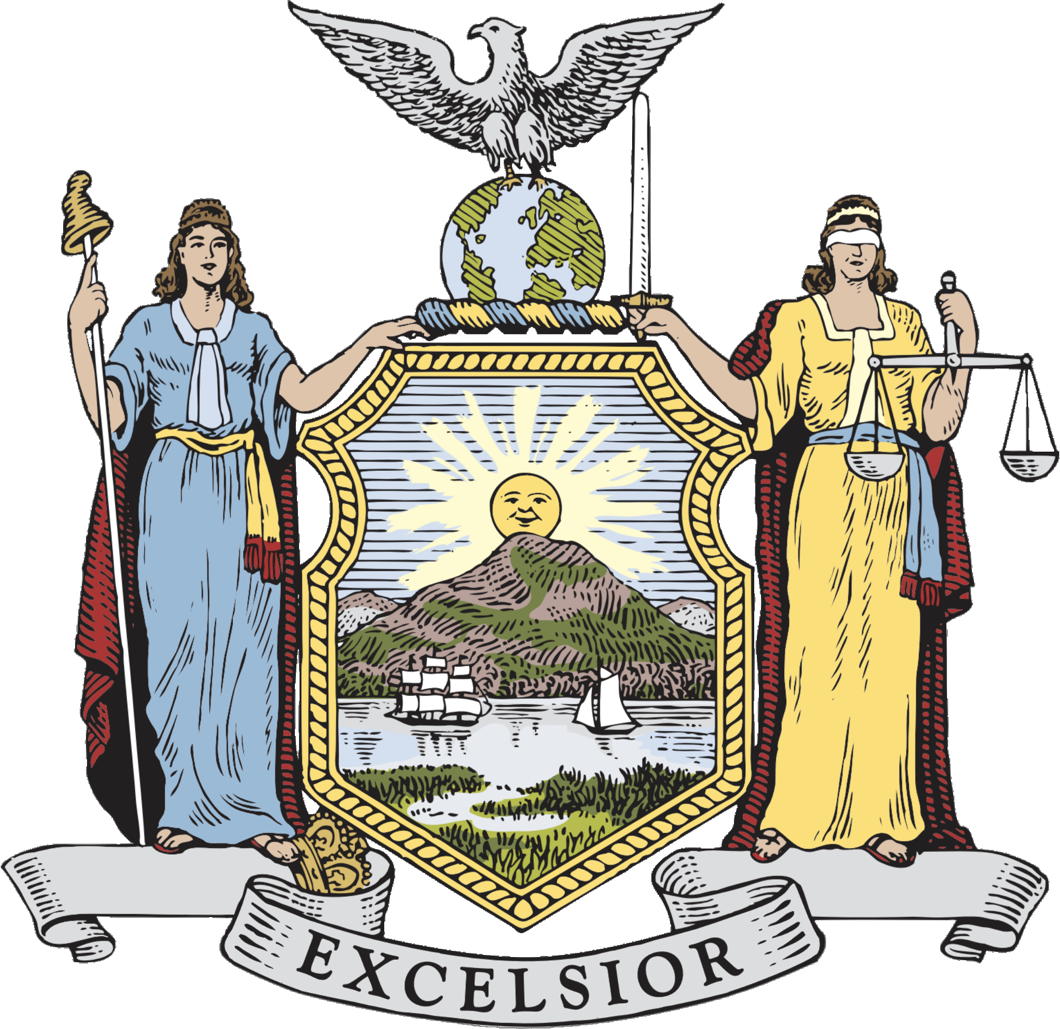

Gaze upon its beauty, for you will see it fade. Azure, in a landscape, the sun in fess, rising in splendour or, behind a range of three mountains, the middle one the highest; in base a ship and sloop under sail, passing and about to meet on a river.

This beautiful device was adopted by the very first Assembly and Senate of the State of New York back in 1778, having been designed a year earlier. It has remained substantially unchanged since the 1880s until Governor Cuomo in one of his fits of fancy decided to sneak a change via the state budget, of all things.

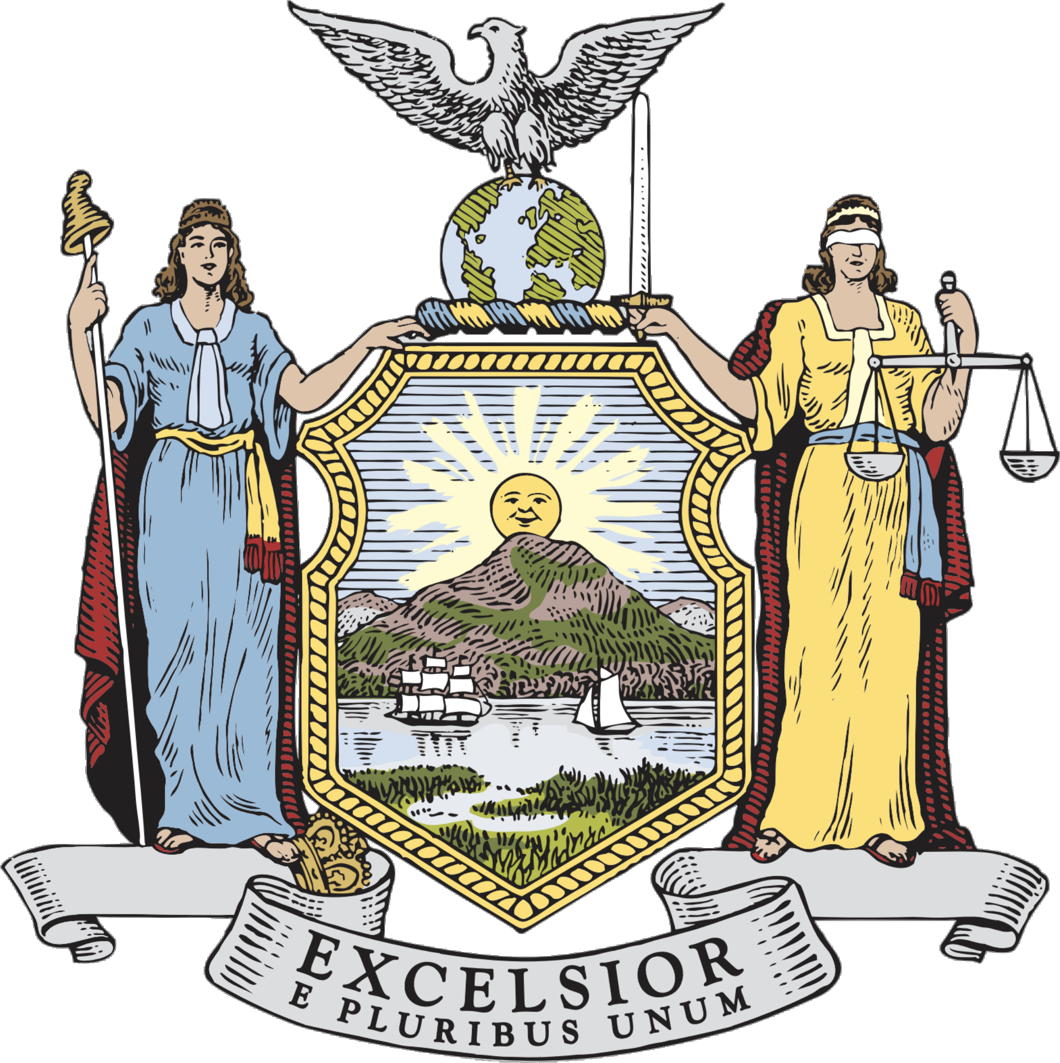

“In this term of turmoil, let New York state remind the nation of who we are,” Governor Cuomo said in his State of the State address in January of this year. “Let’s add ‘E pluribus unum’ to the seal of our state and proclaim at this time the simple truth that without unity, we are nothing.”

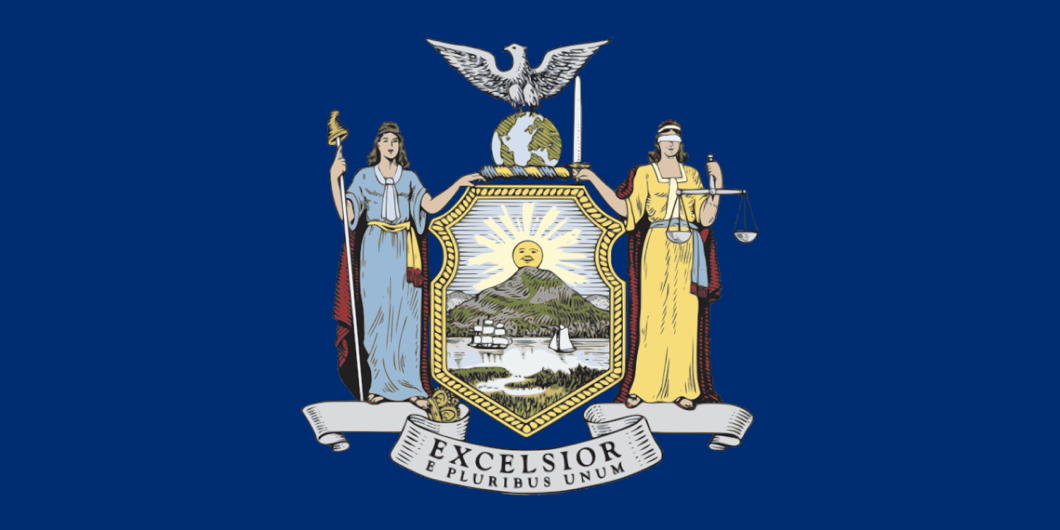

Why the national motto should be interjected into the state flag when we have our own motto is beyond me. Rather than introduce a bill that would allow an open debate on the matter, the Governor decided to sneak it into the state budget. This passed in April, so the coat of arms, great seal, and flag of the state of New York have all now been altered to include the superfluous words.

That said, I have a sneaking suspicion the change might be honoured more in the breach than in the observance. Flag companies doubtless have a large back supply of pre-Cuomo flags to shift and customers are rarely up to date on matters vexillological and heraldic. I suspect that the next time you float down Park Avenue and see the giant banners fluttering from corporate headquarters very few will have updated their state flag.

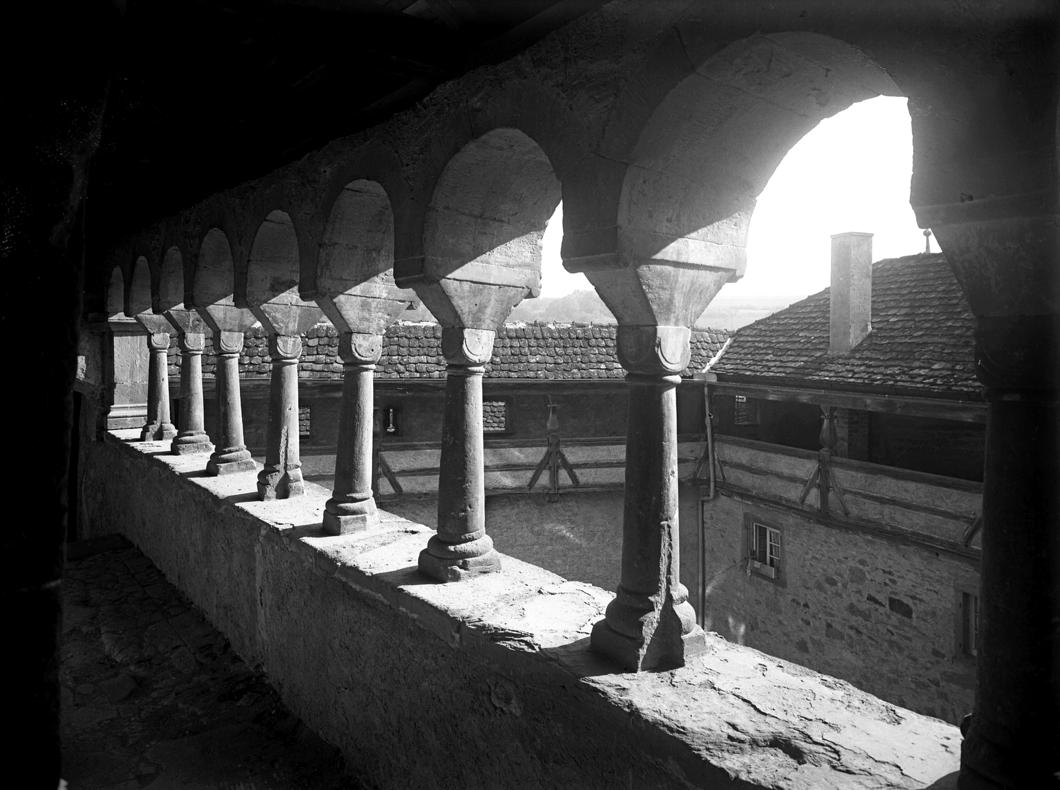

Großcomburg

While the old basilica was demolished in the 1700s and replaced with a baroque creation there is still plenty of Romanesque abiding at Großcomburg in Swabia. The monastery was founded in 1078 and the original three-aisled, double-choired church was consecrated a decade later. Its community experienced many ups and downs before the Protestant Duke of Württemberg, Frederick III, decided to suppress the abbey and secularise it. Many of its treasures were melted down and its library transferred to the ducal one in Stuttgart where its mediæval manuscripts remain today.

From 1817 until 1909 the abbey buildings were occupied by a corps of honourable invalids, a uniformed group of old and wounded soldiers who made their home at Comburg.

In 1926 one of the first progressive schools in Württemberg was established there, only to be closed in 1936. Under the National Socialists it went through a variety of uses: a building trades school, a Hitler Youth camp, a labour service depot, and prisoner of war camp.

With the war’s end it housed displaced persons and liberated forced-labourers until it became a state teacher training college in 1947, which it remains to this day.

Black-and-white photography is particular suitable for capturing the beauty and the mystery of the Romanesque.

These images of Großcomburg are by Helga Schmidt-Glaßner, who was responsible for many volumes of art and architectural photography in the decades after the war.

F.X. Velarde: Forgotten & Found

Many of the architects of the “other modern” in architecture were forgotten or at least neglected once the craft moved in a more avant-garde direction.

The British Expressionist architect F.X. Velarde who produced a number of Catholic churches in and around Liverpool in the interwar period and beyond is the subject of a new book from Dominic Wilkinson and Andrew Crompton.

There will be a free online lecture tomorrow on ‘The Churches of F. X. Velarde’ given by Mr Wilkinson, Principal Lecturer in Architecture Liverpool John Moores University. Further details are available here.

The book is available from Liverpool University Press with a 25% discount through the Twentieth Century Society. (more…)

Romes that Never Were

When the splendidly named Saint Sturm – Sturmi to his friends, apparently – founded the Benedictine monastery of Fulda in A.D. 742 we can presume he had no idea that the magnificent church eventually erected there (above) would one day be considered for housing the Supreme Pontiff of the Universal Church.

Rome, caput mundi, is ubiquitously acknowledged by all Christian folk as the divinely ordained location for the Papacy, but this has not always been acknowledged in practice. Most memorable is the “Babylonian Captivity” of the fourteenth century when the papal court was based at the enclave of Avignon surrounded by the Kingdom of Arles. The illustrious St Catherine of Siena was influential in bringing that to an end.

Since the return from Avignon the Successor of Peter has prudently been keen to stay in Rome, but various crises over the past two centuries have seen His Holiness shifted about. General Buonaparte successively imprisoned Pius VI and Pius VII while he made to refashion Europe in his likeness, and the later slow-boil conquest of the Italian peninsula by the Kingdom of Sardinia caused much worrying in the courts of the continents as well.

In 1870, the Eternal City fell to the troops of General Cadorna, and while the Vatican itself was not violated it was widely assumed the papacy could not stay in Rome. Pope Pius IX evaluated several options, one of them seeking refuge from – of all people – the Prussian king and soon-to-be German emperor Wilhelm I.

Bismarck, no ally of the Church, but shrewd as ever, was in favour of it:

I have no objection to it — Cologne or Fulda. It would be passing strange, but after all not so inexplicable, and it would be very useful to us to be recognised by Catholics as what we really are, that is to say, the sole power now existing that is capable of protecting the head of their Church. …

But the King [Wilhelm I] will not consent. He is terribly afraid. He thinks all Prussia would be perverted and he himself would be obliged to become a Catholic. I told him, however, that if the Pope begged for asylum he could not refuse it. He would have to grant it as ruler of ten million Catholic subjects who would desire to see the head of their Church protected. …

Rumours have already been circulated on various occasions to the effect that the Pope intends to leave Rome. According to the latest of these the Council, which was adjourned in the summer, will be reopened at another place, some persons mentioning Malta and others Trent.

Bismarck mused to Moritz Busch what a comedy it would be to see the Pope and Cardinals migrate to Fulda, but also reported the King did not share his sense of humour on the subject. The advantages to Prussia were plain: the ultramontanes within their territories and throughout the German states would be tamed and their own (Catholic) Centre party would have to come on to the government’s side.

In the end, of course, the Pope decided to stay put in Rome and became the “Prisoner of the Vatican”, surrounded by an awkward usurper state that made attempts at friendship without betraying its hopes for legitimising its theft of the Papal States. It was the diplomatic coup of the Lateran Treaty in 1929 that finally allowed both states to breathe easy and created the State of the City of the Vatican, an entity distinct from but subservient to the Holy See of Rome.

The Second World War brought its own threats to the Pope’s sovereignty, and the wise and cautious Pius XII feared he might be imprisoned by Hitler just as his predecessor and namesake had been by Buonaparte. Pius was determined the Germans would not get their hands on the Pope and so signed an instrument of abdication effective the moment the Germans took him captive. He would have burnt his white clothing to emphasise that he was no longer the Bishop of Rome.

The record is not yet firmly established but it is rumoured that the College of Cardinals was to be convened in neutral Éire to elect a successor. One wonders where they would have met. The Irish government would undoubtedly have put something at their disposal — Dublin Castle perhaps? Despite the whirlwind of war, the election of a pope in St Patrick’s Hall would have warmed the cockles of many Irish hearts.

But what then? Ireland’s neutrality would have been useful but a German violation of the Vatican’s territory would have been grounds for open, though obviously not military, conflict. Further rumours, also totally unsubstantiated, had it that the King of Canada, George VI, quietly had plans drawn up for offering the Citadelle of Quebec to the Pope to function as a Vatican-in-Exile. Others claim it wasn’t until the 1950s that Quebec was investigated as a possibility by the Vatican in case Italy went communist, as was conceivable.

So Cologne, Fulda, Malta, Trent? None of these plans ever occurred, thank God.

And what about England? Why not? The court of St James and the Holy See, despite obvious and significant differences, enjoyed close relations and overlapping interests in many particular circumstances from the Napoleonic wars until present. Pius IX had put feelers out to Queen Victoria’s minister in Rome, Lord Odo Russell, in 1870 but the British ambassador more or less told him of course the Pope would be welcomed in England but don’t be silly, the Sardinians would never conquer Rome.

One imagines the British sovereign would grant a palace of sufficient grandeur to the exiled Pontiff. Hampton Court would do the job. It’s far enough from the centre of London but large enough to house a small court and the emergency-time administration of the Holy Roman Church. Would the ghost of Cardinal Wolsey plague the Princes of the Church?

Thanks be to God, we’ve never had cause to find out. At Rome sits the See Peter founded and so it looks to remain. Ubi Petrus, ibi ecclesia.

Get thee to a Lamasery

In defence of Lost Horizon

by ALEXANDER FRANCIS SHAW

Death hath no sting because I know that — on the other side of the planet — glass elevators whisper fifty-six storeys from a marble lobby to rooms of crisp white sheets and burgundy damask. The carpets are thick, the tables polished. Decanters are flushed with guava and grape. In a kaleidoscope of silver and ice, glasses of salad and sorbet are heaped with pearlescent foam, salmon and beluga.

And in one corner, in another time, Alexander Shaw fell asleep in the late afternoon, cheek pressed against the silk wing of an armchair as his gaze followed the plunge of a falcon from the Peak, through the skyscrapers, and out over Victoria Harbour. A soft audio moquette of Morrecone and Mahler accompanied the CNN news ticker and extraneous weather synopses: Sydney — sun… Los Angeles – overcast… Doha – sun… Cape Town – rain…

Please excuse the fetishism. My point deserves this tantric preamble.

If Pugin had been a Qing rather than a Victorian he might have made a start to all this, but today the backlit Onyx, the Pacific sixteen-storey silk frieze, the Qipao uniforms, and the Olympian scale of everything behove only the mighty Orient.

Why so? The Island Shangri-La Hotel is named for the fictional utopia in James Hilton’s Lost Horizon. And right there you have the problem: ‘utopia.’ The martial cultures of the East don’t comprehend the pre-echoes in that word.

Credit where it is due, the sublimation of the individual into the Gestalt (I’ll call it Gung-Ho, because that sounds like a legitimate school of oriental philosophy) is in stark contrast to the game we play with ourselves the West. Because they’ve never been saddled with accountability for the state of their societies, the Chinese haven’t had the opportunity to be disillusioned by their own idealism. A Chinese man has never had to look at himself in the mirror and realise that he buggered things up by voting for Hitler or joining a Black Lives Matter march.

Absent any higher purpose, we, on the other hand, must seek redemption for each hypocrisy and failure of our great civilisation, dumbing down in hand-wringing apologia for our very existence. Thus have we developed a misnomered ‘meekness’ of niceness, indecision, and half-measures. To believe in our superiority is to be saddled with shame – and shame is a force distinct from guilt in that it seeks remission by reference to others’ perception. You can quietly abort a child with Down Syndrome provided that you demonstrate your humanity by promoting BAME representation, carbon austerity, and the moxie of women who have the mystique of cement mixers.

A second example: the lobby-girl at the Grand Hyatt, Shanghai. Given that half the wealth of the Orient passes through those doors, some central planning committee evidently felt it prudent that the city’s 24 million citizens be combed for the sweetest smile to greet it. When I returned, breath held, a year later, she had been matched by another matchless angel.

Which brings us to the human source of utopianism – the quest for eternity. The plane-wrecked protagonists of Hilton’s novel experience a Himalayan valley of youth governed by an AWOL and arguably mad 250-year-old Luxembourgish priest. Father Perrault governs Shangri-La from a lamasery of almost obscene opulence (imagine – green bathtubs!). The guests are tastefully divided in their credulity about whether the society is an illusion and the book was devoured by an escapist West suffering the Great Depression.

Rifling my free copy in Hong Kong, I judged it the Englishman’s analogue to the continental cults whose glorious living and glorious dead are distanced by a Napoleonic boulevard of culture and commerce where the stick and carrot are applied. It seemed fortunate that the British are only really any good at stoking a frisson for utopian demise and, as the distant red flags fluttered and my Mao-faced banknotes smirked at me from their money clip, I designated Lost Horizon – and all this – to a fantastic past which would be swept away by Western humility and moderation.

I was wrong and, what is more, I’m glad I was wrong.

Since the collapse of any credible European adversary, Britain has turned inwards in its quest for maudlin schadenfreude. Our woke egalitarianism means everyone must de-mask or debunk any superiority as somehow an act.

I hazily recall a heavy session at the London Ritz at which the bar-chef challenged me to draw my sgian-dubh to establish whether I was carrying an offensive weapon. I was quick-witted enough to reveal my purist stand on another wager of the kilted gentleman which duly precipitated a less troublesome ejection from the premises. But how did we sink to this? Is there anywhere outside of the glittering palaces of sinister dictatorships where a man can live honestly without some spiv trying to trip him up?

More poignantly, perhaps, how can the professionals themselves avoid clientele who know their own job from experience and think they have ‘made it’ because they bussed tables in their student days?

Lost Horizon has at its heart a provocation to serve which the maladjusted West will now struggle to perceive. Utopia should be viewed not as a deception but rather the absence of the contempt for the familiar. The point of Shangri-La is that it was built by strangers in exotic lands for strangers in exotic lands. Lo-Tsen, for whom the valley was home, is repelled by its treasures and risks her life in order to leave. Hugh Conway – the knackered British diplomat at the centre of the novel – appears to have risked his life in order to return, inspiring the enchanted discussion among pilots which opens the book on the darkening concourse of Templehof airport in 1933.

Like the bedraggled Conway, we must keep our eyes fixed on utopia so that our journey becomes a pilgrimage with a view to one day opening the doors of our own Shangri-La.

And so much for the better if nobody follows.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories