2019 March

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

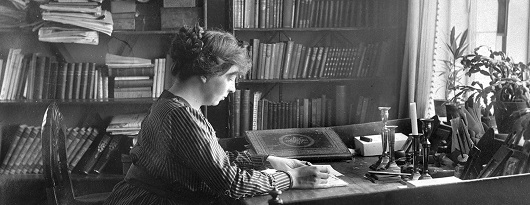

Understanding Undset

Sigrid Undset’s is doubtlessly among the twentieth century’s greatest writers, even though Kristin Lavransdatter, her main works of literature, is set in the fourteenth century. At the ceremony awarding Undset the 1928 Nobel Prize for Literature, Per Hallström described the writer’s narrative as “vigorous, sweeping, and at times heavy”:

It rolls on like a river, ceaselessly receiving new tributaries whose course the author also describes, at the risk of overtaxing the reader’s memory. […] And the vast river, whose course is difficult to embrace comprehensively, rolls its powerful waves which carry along the reader, plunged into a sort of torpor. But the roaring of its waters has the eternal freshness of nature. In the rapids and in the falls, the reader finds the enchantment which emanates from the power of the elements, as in the vast mirror of the lakes he notices a reflection of immensity, with the vision there of all possible greatness in human nature. Then, when the river reaches the sea, when Kristin Lavransdatter has fought to the end the battle of her life, no one complains of the length of the course which accumulated so overwhelming a depth and profundity in her destiny. In the poetry of all times, there are few scenes of comparable excellence.

Obviously Kristin Lavransdatter must be read for itself. I started reading it in the Stellenbosch University library a decade ago and was able to finish it thanks to being given a copy by a kindly Premonstratensian.

But the woman behind Kristin wrote more: her biographical essays and other works (like the one describing a visit to Glastonbury) are just as enjoyable and insightful.

At First Things, Elizabeth Scalia describes Undset’s lives of saints and holy men and women in Sigrid Undset’s Essays for Our Time.

Stephen Sparrow reveals much of Undset’s own biographical detail and how this influenced her writing in Sigrid Undset: Catholic Viking.

But the best essay I’ve read on Sigrid Undset so far is David Warren’s meditation on womanhood, motherhood, and Kristin Lavransdatter. I don’t agree with everything he says (I rather enjoyed the new translation but am thinking I might have to give the old one a go), but David gets Kristin the character, gets Kristin the novel, and gets the way that life is refracted through both.

Read David Warren, then read Sigrid Undset.

Lady Day

Today is Lady Day, the Feast of the Annunciation when the Archangel Gabriel appeared to the Blessed Virgin Mary and announced that she would conceive and bear the child Jesus.

The angelic salutation – “Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee… Blessed art thou amongst women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus” – forms the basis of the Ave Maria, one of the most widely uttered prayers in Christendom.

Traditionally this has been one of the greatest of devotions to the Virgin amongst the English, which is why there are so many pubs across England named ‘The Salutation’.

For centuries in England and Scotland (as well as elsewhere), Lady Day was the first day of the calendar year. Scotland moved this to 1 January in 1600 and England did likewise in 1750.

Nonetheless, the English tax year is still based on this date as it commences on 6 April, which is the Annunciation plus twelve days to mark the difference between the old Julian calendar and the modern Gregorian one.

In the realms of fiction, 25 March is the day Tolkien chose for when Frodo destroyed the Ring in Mount Doom, securing the fall of Sauron – with obvious parallels to Christ’s Incarnation securing the defeat of Satan.

This stained glass roundel above is not English, however, but from the Southern Netherlands around 1500-1510.

Elsewhere, A Clerk of Oxford has a good section on the Annunciation.

Haussmanhattan

Paris and New York are two cities radically different in design and character, but they are smashed together in this little project from architect Luis Fernandes.

‘Haussmanhattan’ is a portmanteau of Baron Haussmann, the Prefect of the Seine whose reconfiguration of the French capital made it the Paris we know today, and Manhattan, the most renowned of New York City’s five boroughs.

Haussmann’s plan of broad boulevards and radial avenues is a far cry from the artless Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 which created the unforgiving city blocks that colonised the entire island of Manhattan ad infinitum.

The contrast only makes the pick-and-mix Fernandes has confected all the more fun/ridiculous/interesting.

Sir John Soane

Sir John Soane still looms over the intervening centuries of architecture and design in Great Britain, but I’ve never actually known what he looked like. Apparently this is him, in an 1804 portrait by William Owen.

Everyone’s been to his house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, but Pitzhanger Manor, his place in the country (though Ealing hardly seems rural today) was recently reopened after serious conservation works ongoing since 2015.

Hope to pay it a visit soon.

The Rensselaer Window

The patroonship of Rensselaerswyck was erected in 1630 giving its patroon, Kiliaen van Rensselaer, feudal powers over a large parcel of land on the banks of the Hudson River. Despite exercising a strong influence on the growth and development of New Netherland and the Hudson Valley, Kiliaen never actually stepped foot in the new world but kept close control of his domain from across the ocean in Amsterdam.

Jan Baptist was Kiliaen’s second surviving son, and served as director at the ‘colony’ as it was often known from 1652 to 1658. He commissioned Evert Duyckinck to make this painted-glass window displaying his coat of arms in 1656 and gave it to the Dutch Reformed Church in Beverwyck (today’s Albany).

While the congregation still exists — and celebrated its 375th anniversary in 2017 — the original church was demolished in 1805 and the window moved to the Van Rensselaer Manor House which itself survived til 1890 before facing the wrecking ball. The window was preserved and was left to the Metropolitan Museum of Art through the 1951 bequest of Mrs J. Insley Blair and while well documented it does not appear to be on display at the moment.

The patroonship itself was converted into a manorial lordship by the English authorities after they took over and survived until it was broken up amongst relatives after the death of Stephen van Rensselaer III in 1839.

This last great patroon had proved an indulgent lord and the efforts of his inheritors to claim uncollected back rents led to the 1839-1845 “Helderberg War” or “Anti-Rent War” of tenants revolting against the system. The great landholders, seeing the end was nigh, were convinced to sell up and in 1846 the state of New York adopted a new constitution abolishing feudal tenure. The era of patroonships and manors in the Hudson Valley had come to an end.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories