About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

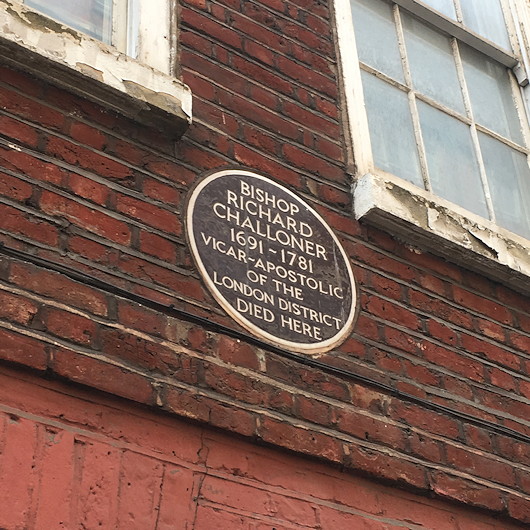

Challoner’s House — Rather humble for an episcopal palace, but such was the function of No. 44, Old Gloucester Street in Holborn during the time of Bishop Richard Challoner.

If it seems an odd spot for London’s Catholic bishop, it can be explained by its close proximity to the chapel of the Sardinian Embassy off Lincoln’s Inn Fields. At this time, of course, the Mass was still illegal and the only places Catholics in London could worship were the embassies of the Catholic nations. To protect the underground bishop, the house in Old Gloucester Street was actually rented in the name of his housekeeper, Mrs Mary Hanne.

After a perfect breakfast on Saturday morning the sun was shining so I decided the three-and-a-half miles home from St Pancras were best managed on foot. If architectural or historical curiosities are your fancy then foot is the way to travel, and so it was by pure chance that I stumbled upon No. 44. It seemed particularly appropriate that the night before a whole gang of us — Brits, Swedes, Italians, etc. — had been drinking in the Ship Tavern in Holborn where Bishop Challoner was known to offer the occasional clandestine Mass.

No. 44 was identified as the house in which he died by E.E. Reynolds in 1950. Born a Quaker, Reynolds (better known as “Josh”) was deeply involved in the Scouting movement and converted to Catholicism during the war. He involved the Catholic Record Society — England’s academic body for national Catholic history — in the effort to raise money to have a plaque put on Challoner’s last dwelling place.

The plaque’s unveiling was reported in the Tablet of 6 November 1954:

The house, No. 44, is a pleasant, small one, which cannot have been long built when Challoner went to live there ; today it has many occupants, whose necks craned forward from all the windows to watch last Saturday’s proceedings : the arrival of the Cardinal, who was welcomed by Brigadier Trappes-Lomax and his fellow-menibers of the Council of the Catholic Record Society, on whose initiative the plaque had been erected ; the arrival also of the Bishop of Southwark and the Mayor of Holborn ; and then the ceremony, a brief unhitching of cords to lower the flag with which the plaque had been covered — not a papal flag, but a Union Jack, which Challoner himself would not have recognized, for the national flag did not carry the cross of St. Patrick in his day. The plaque revealed is circular, very much in the regulation pattern of the LCC, only chocolate-coloured instead of the LCC’s light blue.

A colony of Catholics lived in this part of Holborn in the eighteenth century, as the Cardinal recalled in a short address after the ceremony ; for it was convenient for the Sardinian Chapel in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. There, under the protection of the Ambassador, Challoner was able to say Mass, and the faithful to assist. And, the Cardinal went on to remind us, Challoner used also to say Mass in stables in Whetstone Park and in Clare Market—both nearby—as well as preaching and giving instruction at the Ship Tavern, just across Holborn, in Little Turnstile. […]

For fifty years Challoner lived in the district, changing his lodgings fairly often in order to avoid the attentions of informers. A woman at present living in Old Gloucester Street said on Saturday that when she moved there, only about ten years ago, there was still a verbal tradition in the street that Bishop Challoner, of whom she had not heard before, had lived there, had been much loved locally, and had been protected from his pursuers by his fellow-residents.

Not a bad find for a Saturday afternoon’s wander.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories

Worthy of remark, not only in itself, but also as an example of what will soon be the common way of life, not only of faithful bishops, but of the true pope himself.

See my chapter (below)

“The architectural setting of Challoner’s episcopate”, in Eamon Duffy (ed),Challoner and his church:a Catholic bishop in Georgian England, (Darton Longman and Todd,1981), pp. 55-70.