2017 December

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

St Paul’s Survives

Crossing the Thames as I walked home from the pub last night, I looked down the river and saw the sturdy dome of St Paul’s standing out, illuminated in the winter night.

As it happens, it was exactly seventy-seven years ago last night — on the 29th of December 1940 — that the iconic photograph often called ‘St Paul’s Survives’ (above) was captured.

Hopeful as that sight must have been, it was a pretty grim time. But four and a half years later (below) the cathedral was illuminated not by the lights of enemy firebombs but by great searchlights forming a massive ‘V’ in the sky: it was 8 May 1945 — Victory in Europe.

Another year gone. We’ve survived.

Warwick Street Church

Over in Soho there is a curious little church with a fascinating history. The parish of Our Lady of the Assumption & St Gregory in Warwick Street started out as the house chapel for the Portuguese embassy in Golden Square, later occupied by the Bavarian embassy.

In recent years the Archdiocese of Westminster has placed the church in the care of the Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham, and they have put new life into the strong musical tradition of the parish.

As chance would have, in my capacity as a professional web designer I was commissioned to design a new website for the parish.

You can view the new Warwick Street website here, and read a little more about its interesting history and architecture.

“Events did not choose the terrorists; powerful white people did.”

Helen Andrews on Zimbabwe

Robert Mugabe leading Ian Smith into the Zimbabwean parliament, 1980.

It is rare to find journalism as informed and insightful as this piece on Zimbabwe by Helen Andrews in National Review. In the aftermath of Mugabe’s clumsy downfall and his succession by a powerful apparatchik and experienced political operator, Helen explores the Rhodesian crisis and attempts to answer the question: could it really have gone any other way?

Any idea that liberal reform on the part of the Rhodesian state could have saved it is a non-starter, because the anti-imperialists were implacable and — I do not know a gentle way to put this — they were quite happy to lie. I do not mean just the professional liars of the Soviet propaganda shop, or the pundits who lazily referred to the Rhodesian system as “apartheid,” or the guerrillas who told Shona villagers that ZANU had successfully dynamited the Kariba Dam, or the foreign journalist who scattered candy around a garbage bin and captioned the resulting photo “Starving children searching for food in Salisbury.” Ralph Bunche had a doctorate from Harvard, a Nobel Peace Prize, and a co-author credit on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and when it came to imperialism, he lied.

“Colonial authorities like the noted Englishman, Lord Lugard, doubt that the African race, whether in Africa or America, can develop capability for self-government.” When I first read that in Bunche’s 1936 pamphlet “A World View of Race,” I felt a lurking suspicion that I had read a sentence of Lord Lugard’s beginning with the very words “The method of their progress toward self-government lies…” I had. His next words are “along the same path as that of Europeans.” Even making allowances for CTRL-F’s not having been invented yet, Bunche’s remark is plain slander. With Harvard Ph.D.s pulling stunts like this, it is hard to summon much indignation at a garden-variety diplomatic lie like the U.N. claim, by which sanctions were justified, that Rhodesia had committed an act of aggression by maintaining its status quo.

She does go a little easy on Smith, who despite his many strengths was just as willing to play fast and easy with the truth. (He was a politician, after all.) But then as we are so used to hearing that Smithie was a little Hitler it’s a welcome restorative.

When I moved to South Africa, I did so at least in part because I wanted to see it before it became “the next Zimbabwe”. Having come back, I was impressed by the relative robustness of many of its institutions, and the certain robustness of many of its people. Rather than a Zimbabwe-style collapse, South Africa seemed destined for a slow, ungainly descent into perpetual malaise.

The recent ascent of Cyril Ramaphosa – who on behalf of the ANC ran rings round the NP negotiators during the transition talks of the early ’90s – gives hope to many. I’m too cautious to be optimistic, but Mr Ramaphosa is clever, intelligent, skilful, and more likelier to keep the unions on side.

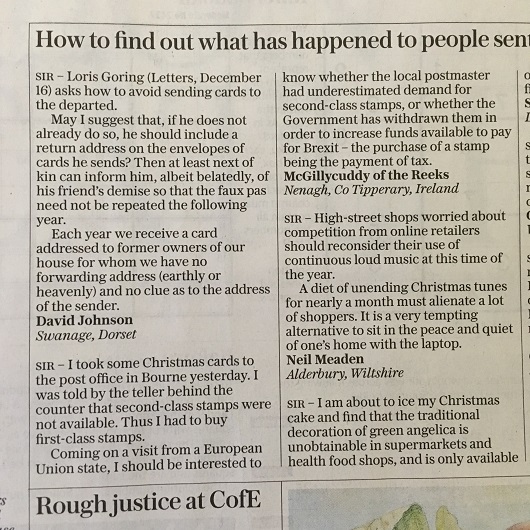

The McGillycuddy of the Reeks

How lovely to see a member of the Gaelic nobility – in this case, the McGillycuddy of the Reeks – having a letter printed in the newspaper (Daily Telegraph, Letters, Wednesday 20 December 2017).

His title is somehow the most fun of all the Chiefs of the Names, though not all bearers of the chiefdom have found it amusing. In the early years of the BBC, the ‘Green Book’ instructing comedy producers what they could and could not get away with contained the instruction ‘Do not mention the McGillycuddy of the Reeks or make jokes about his name’. Clearly a protestation had been made.

Looking at the map of Kerry on my kitchen wall, the eye often drifts to McGillycuddy’s Reeks themselves, the “black stacks” amongst which can be found Corrán Tuathail, Ireland’s tallest mountain.

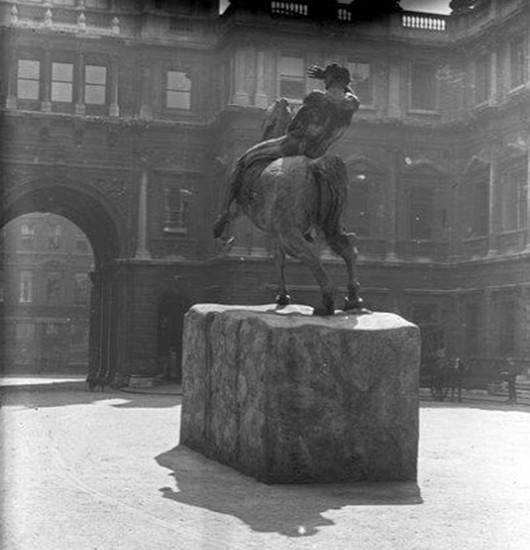

Physical Energy

I came across it by surprise one day, walking through the park. It was almost eerie — all the more so for being unexpected. George Frederic Watts’s sculpture “Physical Energy” was well known to me when I lived in South Africa as it graces the Rhodes Memorial in Cape Town — a rough Greek temple staring out northwards into the vast continent of Africa, as Rhodes himself liked to do.

Unknown to me, another cast of the statue was made and given to the British government, which placed it in Kensington Gardens. It was this copy I stumbled upon while traversing the park to Lily H’s drinks party in the garden of Leinster Square.

It is one of the most aptly named sculptures I can think of, as there is a raw brutish physicality to it, and somehow a sense of tremendous force, power, and energy. Watts was primarily a painter, so that he achieved this great work of sculpture is all the more remarkable. I don’t actually like it: there is something uncomforting and almost vulgar about it, or perhaps just taboo. (Like Rhodes himself.) But it is amazing all the same.

While “Physical Energy” is primarily associated with Cecil Rhodes it was not commissioned in his honour. Watts conceived it in 1886 after having done an equestrian statue for the Duke of Westminster. The first cast wasn’t made until 1902 and was exhibited at the Royal Academy for the first time in 1904 (above).

From there it made its way to Cape Town where it stands today a vital component of the monument to Rhodes. (It even features as the crest on Rhodes University’s coat of arms.) The second cast from 1907 is this one that sits in Kensington Gardens, while a third cast from 1959 now sits beside the National Archives of Zimbabwe in Harare.

This year the Watts Gallery in Surrey commissioned a fourth cast to commemorate the two-hundredth anniversary of the artist’s birth — and that cast now flaunts its bronze in the courtyard of the Royal Academy. It remains on view until the Cusackian birthday in March 2018.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

- Katalin Bánffy-Jelen, R.I.P. March 3, 2025

- Substack Cusackiensis March 3, 2025

- In the Courts of the Lord February 13, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories