2013 November

About Andrew Cusack

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London.

Writer, web designer, etc.; born in New York; educated in Argentina, Scotland, and South Africa; now based in London. read more

News

Blogs

Reviews & Periodicals

Arts & Design

World

France

Mitteleuropa

Knickerbockers

Argentina

The Levant

Africa

Cape of Good Hope

Netherlands

Scandinavia

Québec

India

Muscovy

Germany

Academica

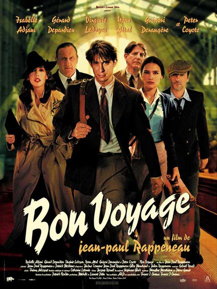

‘Bon Voyage’

Jean-Paul Rappeneau’s ‘Bon Voyage’ (2003) is one of those superb films that come around all too rarely. It manages to balance perfectly all the elements of drama, comedy, action, and romance, set in a convincing historical context.

Bon Voyage

Jean-Paul Rappeneau

2003, France

1 hour 54 minutes

In 1940, Viviane Denvert (played by Isabelle Adjani) is a fickle, self-promoting film star who enlists her childhood friend, Frédéric Auger (Grégori Derangère), to extract herself from a compromising situation. As war creeps upon France, Auger finds himself behind bars for Viviane’s crime, but in the confusion of battle he manages to escape with the seasoned ne’erdowell Raoul (Yvan Attal). All of Paris is fleeing the German advance, and on the train to Bordeaux the two come across physics student Camille (Virginie Ledoyen) who helps them reach the western city by car when the train is stopped on the line.

In Bordeaux we come across government minister Jean-Étienne Beaufort, Viviane’s lover whom she uses to get Frédéric out of a sticky situation resulting from her own manipulation of him. Meanwhile, with all of Paris in Bordeaux, Viviane comes across another ex-paramour, Alex Winckler (Peter Coyote), keeping an unnatural interest in the affairs of the government, while the physics student Camille and her mentor Professor Kopolski are harbouring an important cargo they are determined must not fall into the hands of the Germans.

For fear of spoilers, that is all I will say about the plot, but it all comes packaged in a score by Gabriel Yared, better known for his scoring of ‘The English Patient’, ‘The Talented Mr. Ripley’, and Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s ‘Das Leben der Anderen’. The film was nominated for eight César awards in 2004 — best costumes, best director, best editing, best film, best original score, best sound editing, best supporting actor, and best writing — while it won three Césars that year for photography, best set design, and, for Grégori Derangère, best promising actor. (more…)

Zeitung für Deutschland

Given my total obsession with the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung it will come as no surprise that my favourite advertising installation is the massive logotype for the world’s greatest newspaper which spans the railway tracks at the Frankfurter Hauptbahnhof.

In glorious Teutonic blackletter, it proclaims the newspaper’s ownership of the city to all comers:

Photo: Erhard Bernstein

And while it looks great in daylight, as the evening descends it is illuminated in neon blue. Like the FAZ itself, old-fashioned and modern all in one.

Photo: Otzberg

Diary

It is truly a sad thing for a summer to end, and yet it is an inevitable part of the endless cycle of life. July was full of its annual rites: two weeks in Lebanon and then the traditional festivities associated with the return of the OMV contingent from Lourdes — jugs of Pimm’s at the Scarsdale followed by the manic dinner, drinks, dancing, and smoking at Pag’s late into the night. Miss S. had always avoided the Pag’s part of the festivities, decrying it as a futile attempt to prolong the jollity. She decided to come along this year, however, and enjoyed it so much she stayed well past two in the morning. In fact, I think she was still there when I left.

So it didn’t really seem like summer really kicked off until August. (more…)

The Tragedy of Romeo and Rosaline

After an interlude of barely a month, the theatrical troupe of Fentiman returned to the Cathedral precincts with a presentation of Sharon Jennings’ play ‘The Tragedy of Romeo and Rosaline’. With the intriguing tagline of ‘Whatever happened to Romeo’s first love?’, the work explores the most famous love story of all time from the perspective of Rosaline, the niece of Capulet mentioned yet never seen in Shakespeare’s play.

A jaunty mix of ancient and modern, ‘Romeo and Rosaline’ includes some brilliant moments in its dialogue, peppered with occasional drops of the Bard’s own lingo and allusive humour ranging from the religious to the architectural. The action moves back and forth between just two locales: Rosaline’s own bedchamber, from which we view Verona, and Friar Lawrence’s cell, where we explore the meaning of transpired events.

Rachel Voldman as Nurse varies from the matronly to the almost sensuous. Philippa Tathum as Rosaline’s pushy mother exudes the confidence tempered by social-climbing of a minor landowner’s wife in colonial Kenya (Fair city of Verona meets the Happy Valley?). Althea Steven’s Rosaline is of course the crux of the action and capably carries off a teenage mix of coquetteishness and self-conscious over-introspection, finally consumed by the tragic epiphany that crowns the play’s final act. The theatregoer is lured in by fun and intrigue only to be hit suddenly with the full implications of has-been-ness.

In the end, ‘The Tragedy of Romeo and Rosaline’ is an exploration of isolation and ex-importance, displaying for us the furled banners of forgotten hopes and dreams, with all the faded, wasted glory of “You were the future, once.” Sharon Jennings has shined a well-aimed arclight on an unexplored realm and revealed the very essence of cathartic tragedy.

Search

Instagram: @andcusack

Click here for my Instagram photos.Most Recent Posts

- Faithful Shepherd of the Falklands April 8, 2025

- Articles of Note: 8 April 2025 April 8, 2025

- Proportionality Destroys Representation April 8, 2025

- Sag Harbor Cinema March 26, 2025

- Teutonic Takeover March 10, 2025

Most Recent Comments

Book Wishlist

Monthly Archives

Categories